Identification of Red Grapevine Cultivars (Vitis vinifera L.) Preserved in Ancient Vineyards in Axarquia (Andalusia, Spain)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

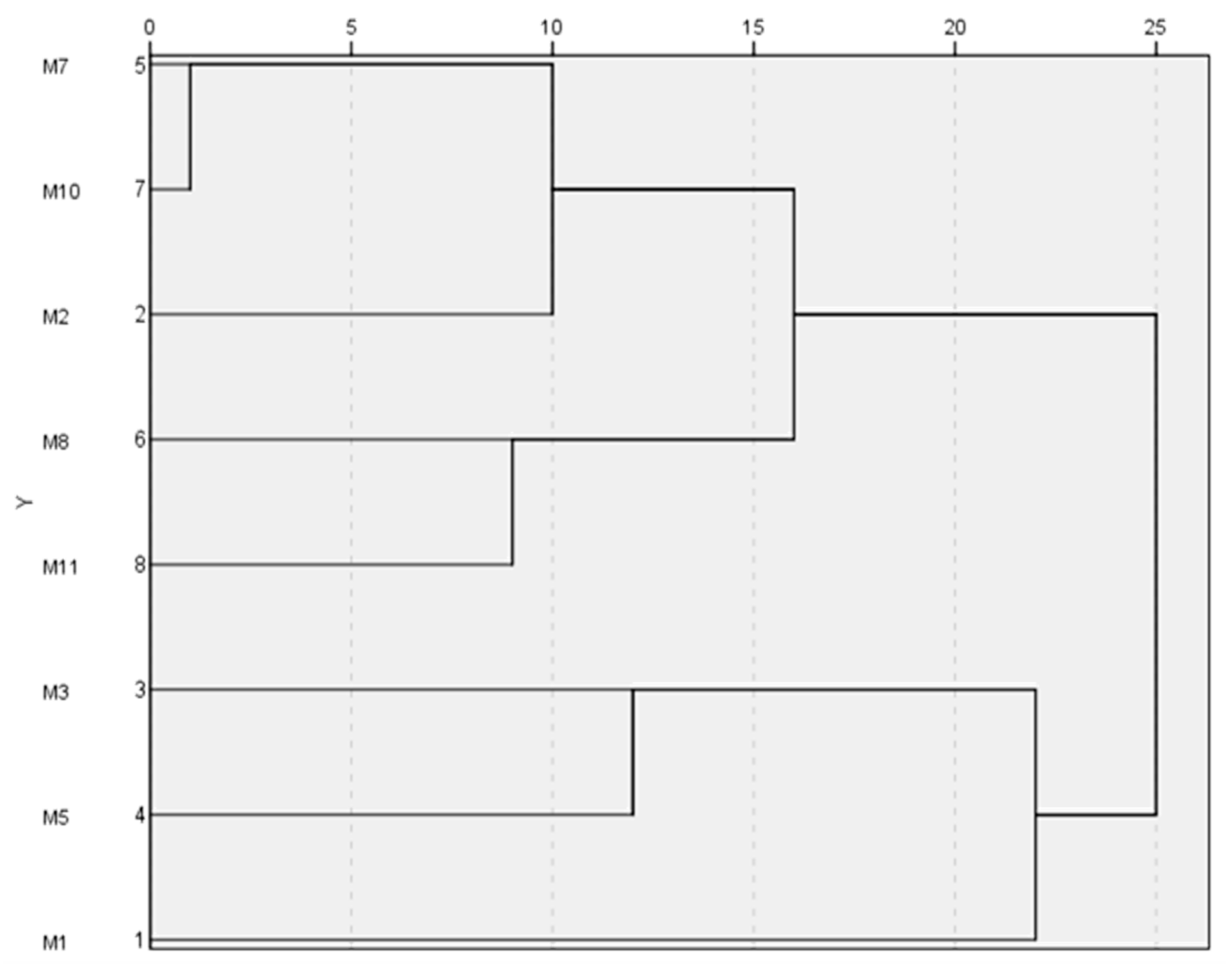

2.1. Microsatellite Analysis

2.2. Ampelographic Characterization

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material

4.2. DNA Extraction and Microsatellite Analysis

4.3. Ampelographic Characterization

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Benabent, M. La Axarquía, un paisaje en proceso de transformación. Rev. PH Inst. Andal. Patrim Histórico 2009, 71, 44–51. [Google Scholar]

- Quintana-Toret, F.J. Origen histórico de la viticultura malagueña. Baetica Estud. Arte Geogr. Hist. 1985, 8, 393–404. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Cantizano, A.; Amores-Arrocha, A.; Gutiérrez-Escobar, R.; Palacios, V. Short communication: Identification and relationship of the autochthonous ‘Romé’ and ‘Rome Tinto’ grapevine cultivars. Span. J. Agric. Res. 2018, 16, e07SC02. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancho-Galán, P.; Amores-Arrocha, A.; Palacios, V.; Jiménez-Cantizano, A. Genetical, morphological and physicochemical characterization of the autochthonous cultivar ‘Uva Rey’ (Vitis vinifera L.). Agronomy 2019, 9, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Muñoz, S.; Muñoz-Organero, G.; De Andrés, M.T.; Cabello, F. Ampelography: An old technique with future uses: The case of minor varieties of Vitis vinifera L. from the Balearic Islands. J. Inter. Sci. Vigne Vin. 2011, 45, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinelabidine, L.H.; Cunha, J.; Eiras-Diaz, J.E.; Cabello, F.; Martínez-Zapater, J.M.; Ibánez, J. Pedigree analysis of the Spanish grapevine cultivar ‘Heben’. Vitis 2015, 54, 81–86. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Zapater, J.M.; Carmona, M.J.; Díaz-Riquelme, J.; Fernández, L.; Lijavetzky, D. Grapevine genetics after the genome sequence: Challenges and limitations. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2010, 16, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De los Salmones, G. La Invasión Filoxérica en España y las Cepas Americanas, 1st ed.; Tipolitografía de Luis Tasso: Barcelona, Spain, 1893. [Google Scholar]

- Carnero, T. Expansión Vinícola y Atraso Agrario 1870–1900. La Viticultiura Española Durante la Gran Depression, 2nd ed.; Ministerio de Agricultura: Madrid, Spain, 1980.

- Ghiara, B. La Vinificación Mediante el Exclusivo Empleo de la Asepsia Industrial, 1st ed.; Escuela Tipográfica Salesiana: Malaga, Spain, 1918. [Google Scholar]

- Clemente y Rubio, S.D.R. Ensayo Sobre las Variedades de la vid Común que Vegetan en Andalucía; Imprenta de Villalpando: Madrid, Spain, 1807. [Google Scholar]

- De la Leña, C.G. Disertación en Recomendación y Defensa del Famoso vino Malagueño Pero Ximen y Modo de Formarlo, 1st ed.; Servicio de Publicaciones y Divulgación Científica de la Universidad de Málaga: Malaga, Spain, 1792. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, M.T.; Gómez, M.D.; López, M.I.; López, M.J. El viñedo en la comarca de «La Axarquía» (Málaga). Situación actual y futuro. Alimentaria 1997, 225, 65–71. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Cantizano, A. Caracterización Molecular del Banco de Germoplasma de vid del Rancho de la Merced. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Cadiz, Cadiz, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Marsal, G.; Méndez, J.J.; Mateo, J.M.; Ferrer, S.; Canals, J.M.; Zamora, F.; Fort, F. Molecular characterization of Vitis vinifera L. local cultivars from volcanic areas (Canary Islands and Madeira) using SSR markers. Oeno One 2019, 4, 667–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipriani, G.; Spadotto, A.; Jurnam, I.; Di Gaspero, G.; Crespan, M.; Meneghetti, S.; Frare, E.; Vignani, R.; Cresti, M.; Morgante, M.; et al. The SSR-based molecular profile of 1005 grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) accessions uncovers new synonymy and parentages, and reveals a large admixture amongst varieties of different geographic origin. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2010, 121, 1569–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.H.; Bae, K.M.; Noh, J.H.; Shin, I.S.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, D.Y.; Hwang, H.S. Genetic diversity and identification of Korean grapevine cultivars using SSR markers. Korean. J. Breed. Sci. 2011, 43, 422–429. [Google Scholar]

- Basheer-Salimia, R.; Lorenzi, S.; Batarseh, F.; Moreno-Sanz, P.; Emanuelli, F.; Grando, M.S. Molecular identification and genetic relationships of Palestinian grapevine cultivars. Mol. Biotechnol. 2014, 56, 546–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Losada, E.D.; Salgado, A.T.; Ramos-Cabrer, A.M.; Segade, S.R.; Diéguez, S.C.; Pereira-Lorenzo, S. Twenty microsatellites (SSRs) reveal two main origins of variability in grapevine cultivars from Northwestern Spain. Vitis 2010, 49, 55–62. [Google Scholar]

- Hizarci, Y.; Ercisli, S.; Yuksel, C.; Ergul, A. Genetic characterization and relatedness among autochthonous grapevine cultivars from Northeast Turkey by Simple Sequence Repeats (SSR). J. Appl. Bot. Food Qual. 2013, 85, 224–228. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Z.; Liu, W.; Li, X.; Tan, W.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, M.; Ren, R.; Ma, X.; Tang, X. Genetic relationships of 34 grapevine varieties and construction of molecular fingerprints by SSR markers. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2017, 32, 942–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyduran, S.P.; Ercisli, S.; Akin, M.; Eyduran, E. Genetic characterization of autochthonous grapevine cultivars from Eastern Turkkey by simple sequence repeats (SSRs). Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2016, 30, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, M.S.; Sefc, K.M.; Eiras-Dias, E.; Steinkellner, H.; Câmara Laimer, M.L.; Câmara Machado, A. The use of microsatellites for germplasm management in a Portuguese grapevine collection. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1999, 99, 733–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Andrés, F.; Martín, J.P.; Yuste, J.; Rubio, J.A.; Arranz, C.; Ortiz, J.M. Identification and molecular biodiversity of autochthonous grapevine cultivars in the “Comarca del Bierzo”, León, Spain. Vitis 2007, 46, 71–76. [Google Scholar]

- Boccacci, P.; Torello-Marinoni, D.; Gambino, G.; Botta, R.; Schneider, A. Genetic Characterization of Endangered Grape Cultivars of Reggio Emilia Province. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2005, 56, 411–416. [Google Scholar]

- Casanova, J.; Mozas, P.; Ortiz, J.M. Ampelography and microsatellite DNA analysis of autochthonous and endangered grapevine cultivars in the province of Huesca (Spain). Span. J. Agric. Res. 2011, 9, 790–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balda, P.; Ibáñez, J.; Sancha, J.C.; de Toda, F.M. Characterization and identification of minority red grape varieties recovered in Rioja, Spain. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2014, 65, 148–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, V.; Pinto-Carnide, O.; Mota, T.; Martín, J.P.; Ortíz, J.M.; Castro, I. Identification of minority grapevine cultivars from Vinhos Verdes Portuguese DOC Region. Vitis 2015, 54, 53–58. [Google Scholar]

- Vitis International Variety Catalogue. Available online: www.vivc.de (accessed on 23 October 2020).

- Jiménez-Cantizano, A.; García de Luján, A.; Arroyo-García, R. Molecular characterization of table grape varieties preserved in the Rancho de la Merced Grapevine Germplasm Bank (Spain). Vitis 2018, 57, 93–101. [Google Scholar]

- Lacombe, T.; Boursiquot, J.M.; Laucou, V.; Di Vecchi-Staraz, M.; Péros, J.P.; This, P. Large-scale parentage analysis in an extended set of grapevine cultivars (Vitis vinifera L.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 2013, 126, 401–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popescu, C.F.; Crespan, M. Combining Microsatellite Markers and Ampelography for Better Management of Romanian Grapevine Germplasm Collections. Not. Sci. Biol. 2018, 10, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, J.P.; Arranz, C.; Castro, I.D.; Yuste, J.; Rubio, J.A.; Pinto-Carnide, O.; Ortiz, J.M. Prospection and identification of grapevine varieties cultivated in north Portugal and northwest Spain. Vitis 2011, 50, 29–33. [Google Scholar]

- Maul, E.; Töpfer, R. Vitis International Variety Catalogue (VIVC): A cultivar database referenced by genetic profiles and morphology. In BIO Web of Conferences, Proceedings of the 38th World Congress of Vine and Wine (Part 1), Mainz, Germany, 5–10 July 2015; EDP Sciences: Les Ulis, France, 2015; p. 01009. [Google Scholar]

- Sancho-Galán, P.; Amores-Arrocha, A.; Palacios, V.; Jiménez-Cantizano, A. Preliminary Study of Somatic Variants of Palomino Fino (Vitis vinifera L.) Grown in a Warm Climate Region (Andalusia, Spain). Agronomy 2020, 10, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tello, J.; Ibáñez, J. What do we know about grapevine bunch compactness? A state-of-the-art review. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2018, 24, 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- This, P.; Boursiquot, J.M. Essai de définition du cépage. Prog. Agric. Vitic. 1999, 116, 359–361. [Google Scholar]

- Carbonell-Bejerano, P.; Royo, C.; Mauri, N.; Ibáñez, J.; Zapater, J.M. Somatic variation and cultivar innovation in grapevine. In Advances in Grape and Wine Biotechnology, 1st ed.; Morata, A., Loira, I., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- De Lorenzis, G.; Squadrito, M.; Brancadoro, L.; Scienza, A. Zibibbo Nero characterization, a red-wine grape revertant of Muscat of Alexandria. Mol. Biotechnol. 2015, 57, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez- Cantizano, A.; Lara, M.; Ocete, M.E.; Ocete, R. Short communication: Characterization of the relic Almuñécar grapevine cultivar. Span. J. Agric. Res. 2012, 10, 454–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancho-Galán, P.; Amores-Arrocha, A.; Palacios, V.; Jiménez-Cantizano, A. Identification and characterization of white grape varieties autochthonous of a warm climate region (Andalusia, Spain). Agronomy 2020, 10, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urrestarazu, J.; Royo, J.; Santesteban, L.G.; Miranda, C. Evaluating the Influence of the Microsatellite Marker Set on the Genetic Structure Inferred in Pyrus communis L. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0138417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.D.E. Trypanotolerance in West African Cattle and the Population Genetic Effects of Selection. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Dublin, Dublin, Ireland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Organisation Internationale de la Vigne et du Vin (OIV). OIV Descriptor List for Grape Varieties and Vitis Species, 2nd ed.; OIV: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Benito, A.; Muñoz-Organero, G.; de Andrés, M.T.; Ocete, R.; García-Muñoz, S.; López, M.A.; Arroyo-García, R.; Cabello, F. Ex situ ampelographical characterisation of wild Vitis vinifera from fifty-one Spanish populations. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2017, 23, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| OIV Code | Accession Code | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | M5 | M6 | M7 | M8 | M9 | M10 | M11 | |

| ssrVrZAG29 | 110 110 | 110 110 | 110 110 | 110 110 | 110 110 | 110 110 | 110 110 | 110 110 | 110 110 | 110 110 | 110 110 |

| ssrVrZAG62 | 187 203 | 185 203 | 203 203 | 187 203 | 203 203 | 187 193 | 187 195 | 187 195 | 187 203 | 187 203 | 187 195 |

| ssrVrZAG112 | 228 228 | 233 245 | 233 236 | 228 233 | 233 236 | 228 233 | 228 236 | 228 236 | 228 236 | 228 236 | 231 236 |

| ssrVrZAG67 | 130 150 | 124 124 | 137 158 | 137 137 | 137 158 | 124 137 | 130 158 | 130 158 | 137 137 | 130 158 | 124 130 |

| VVMD27 | 178 191 | 176 191 | 182 191 | 176 186 | 182 191 | 173 186 | 178 191 | 178 191 | 176 186 | 178 191 | 178 186 |

| VVMD5 | 231 235 | 224 228 | 231 237 | 222 237 | 231 237 | 228 237 | 235 237 | 235 237 | 222 231 | 235 237 | 231 237 |

| VVS2 | 135 143 | 131 148 | 133 156 | 131 150 | 133 156 | 137 150 | 135 143 | 135 143 | 131 150 | 135 143 | 131 143 |

| ssrVrZAG83 | 190 194 | 188 188 | 190 190 | 190 200 | 190 190 | 200 200 | 190 194 | 190 194 | 194 200 | 190 194 | 190 190 |

| VVMD28 | 233 257 | 243 266 | 247 259 | 243 257 | 247 259 | 233 235 | 235 257 | 235 257 | 227 257 | 235 257 | 243 247 |

| VVIh54 | 167 169 | 167 167 | 167 167 | 167 167 | 167 167 | 167 181 | 167 167 | 167 167 | 167 167 | 167 167 | 167 169 |

| VVIn73 | 264 264 | 264 264 | 256 264 | 264 264 | 256 264 | 264 268 | 264 264 | 264 264 | 264 264 | 264 264 | 264 264 |

| VMC1b11 | 185 188 | 167 185 | 188 188 | 173 188 | 188 188 | 185 185 | 185 188 | 185 188 | 173 188 | 185 188 | 185 188 |

| VVMD25 | 239 253 | 247 247 | 253 254 | 239 261 | 253 254 | 237 247 | 239 253 | 239 253 | 239 261 | 239 253 | 239 239 |

| VVIp31 | 186 190 | 188 190 | 190 190 | 180 190 | 190 190 | 190 190 | 176 190 | 176 190 | 180 196 | 176 190 | 180 192 |

| VVMD7 | 241 247 | 247 249 | 231 237 | 247 247 | 231 237 | 237 237 | 237 237 | 237 237 | 237 247 | 237 237 | 237 241 |

| VVIb01 | 290 290 | 290 294 | 290 306 | 290 290 | 290 306 | 290 290 | 290 294 | 290 294 | 290 290 | 290 294 | 290 290 |

| VVIq52 | 84 88 | 82 82 | 84 88 | 88 88 | 84 88 | 82 88 | 82 88 | 82 88 | 84 88 | 82 88 | 84 88 |

| VVMD24 | 210 210 | 212 212 | 208 208 | 208 217 | 208 208 | 208 217 | 208 208 | 208 208 | 208 208 | 208 208 | 208 208 |

| VVIp60 | 317 321 | 317 321 | 321 321 | 317 321 | 321 321 | 305 313 | 317 325 | 317 325 | 317 325 | 317 325 | 317 321 |

| VVMD32 | 250 270 | 262 270 | 248 250 | 238 254 | 248 250 | 238 238 | 254 270 | 254 270 | 238 248 | 254 270 | 254 256 |

| VVIn16 | 150 152 | 148 150 | 150 150 | 152 158 | 150 150 | 152 152 | 152 152 | 152 152 | 152 158 | 152 152 | 150 152 |

| VMC4f3.1 | 166 186 | 180 206 | 182 206 | 178 178 | 182 206 | 172 178 | 186 188 | 186 188 | 178 178 | 186 188 | 172 186 |

| ssrVrZAG79 | 244 254 | 244 252 | 244 254 | 248 258 | 244 254 | 244 244 | 244 254 | 244 254 | 240 258 | 244 254 | 240 244 |

| VVMD21 | 248 248 | 255 265 | 242 255 | 242 248 | 242 255 | 248 257 | 242 248 | 242 248 | 248 255 | 242 248 | 248 248 |

| VVIv67 | 371 375 | 375 389 | 357 375 | 357 365 | 357 375 | 365 371 | 365 375 | 365 375 | 365 365 | 365 375 | 361 365 |

| Genotype | Code Accession | Local Name | Prime Name * |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | M1 | Casiles Negra | MOLINERA |

| II | M2 | Moscatel de Alejandría Tinta | MUSCAT OF ALEXANDRIA |

| III | M3, M5 | Unknown/Cabriel | - |

| IV | M4 | Romé | MONASTRELL |

| V | M6 | Romé | CABERNET SAUVIGNON |

| VI | M7, M8, M10 | Romé | ROMÉ |

| VII | M9 | Romé | PARREL |

| VIII | M11 | Jaén Tinto | JAEN TINTO |

| Accession Code | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OIV Code | M1 | M2 | M3 | M5 | M7 | M8 | M10 | M11 |

| OIV 065 | 9 | 5 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| OIV 067 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| OIV 068 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| OIV 070 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| OIV 071 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| OIV 072 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 |

| OIV 074 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| OIV 076 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| OIV 079 | 3 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 3 |

| OIV 080 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| OIV 081-1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| OIV 081-2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| OIV 082 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 |

| OIV 083-1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| OIV 083-2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| OIV 084 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| OIV 085 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| OIV 202 | 7 | 5 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 7 |

| OIV 203 | 7 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 7 |

| OIV 204 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 9 | 3 | 9 |

| OIV 206 | 5 | 3 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 5 |

| OIV 208 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| OIV 209 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| OIV 220 | 9 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| OIV 221 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| OIV 222 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| OIV 223 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| OIV 225 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| OIV 238 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 7 | 5 |

| OIV 241 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| M1 | M2 | M3 | M5 | M7 | M8 | M10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M2 | 16 | ||||||

| M3 | 12 | 14 | |||||

| M5 | 16 | 14 | 12 | ||||

| M7 | 14 | 14 | 17 | 17 | |||

| M8 | 16 | 15 | 16 | 18 | 6 | ||

| M10 | 14 | 14 | 17 | 17 | 0 | 6 | |

| M11 | 13 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 12 | 9 | 12 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jiménez-Cantizano, A.; Muñoz-Martín, A.; Amores-Arrocha, A.; Sancho-Galán, P.; Palacios, V. Identification of Red Grapevine Cultivars (Vitis vinifera L.) Preserved in Ancient Vineyards in Axarquia (Andalusia, Spain). Plants 2020, 9, 1572. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants9111572

Jiménez-Cantizano A, Muñoz-Martín A, Amores-Arrocha A, Sancho-Galán P, Palacios V. Identification of Red Grapevine Cultivars (Vitis vinifera L.) Preserved in Ancient Vineyards in Axarquia (Andalusia, Spain). Plants. 2020; 9(11):1572. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants9111572

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiménez-Cantizano, Ana, Alejandro Muñoz-Martín, Antonio Amores-Arrocha, Pau Sancho-Galán, and Víctor Palacios. 2020. "Identification of Red Grapevine Cultivars (Vitis vinifera L.) Preserved in Ancient Vineyards in Axarquia (Andalusia, Spain)" Plants 9, no. 11: 1572. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants9111572

APA StyleJiménez-Cantizano, A., Muñoz-Martín, A., Amores-Arrocha, A., Sancho-Galán, P., & Palacios, V. (2020). Identification of Red Grapevine Cultivars (Vitis vinifera L.) Preserved in Ancient Vineyards in Axarquia (Andalusia, Spain). Plants, 9(11), 1572. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants9111572