Dynamic Shifts of Heavy Metals During Mixed Leaf Litter Decomposition in a Subtropical Mangrove

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Experimental Setup

2.3. Parameters’ Calculation

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Dynamic Changes in Heavy Metal Contents During Mixed-Litter Decomposition

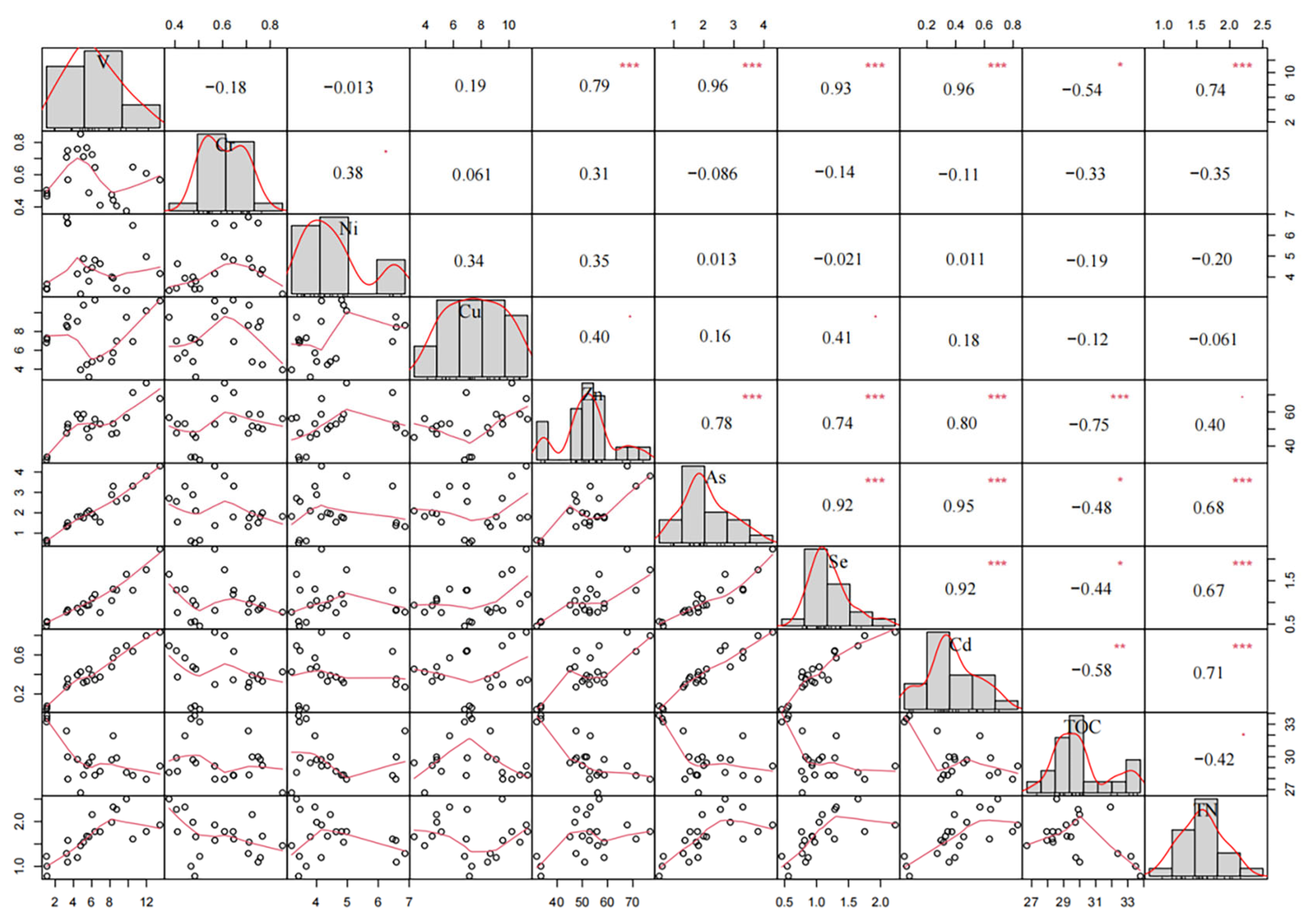

3.2. Correlation Among Heavy Metals, TN, TOC, Carbon/Metal (C/M) Ratios and Carbon/Nitrogen (C/N) Ratios

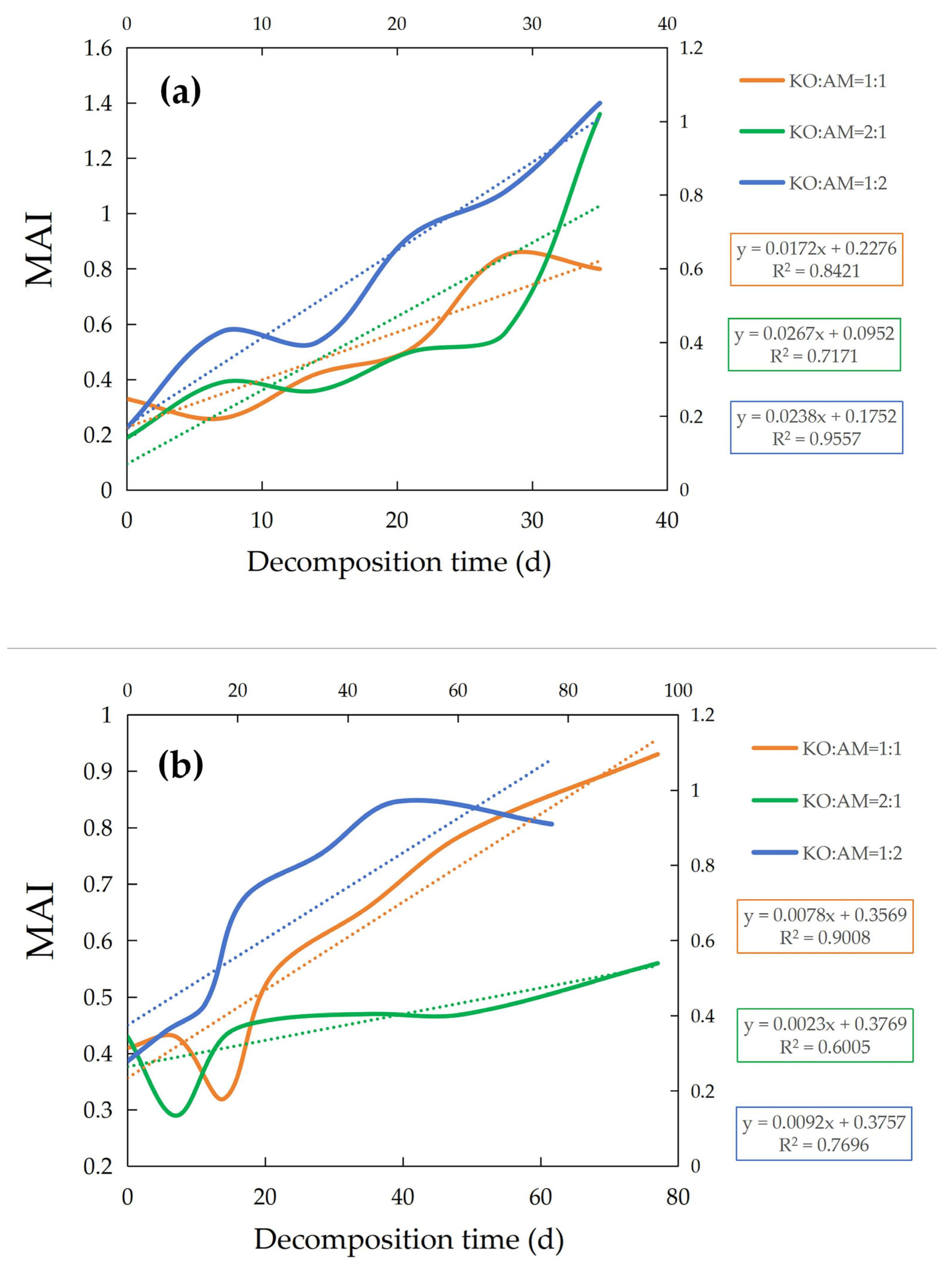

3.3. Dynamic Changes in the Heavy Metals Comprehensive Accumulation Index (MAI) During Mixed-Litter Decomposition

4. Discussion

4.1. Dynamic Analysis of Heavy Metal Contents

4.2. Correlation Analysis of Heavy Metals

4.3. Change in Comprehensive Accumulation Index of Heavy Metals

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Landrigan, P.J.; Stegeman, J.J.; Fleming, L.E. Review: Human Health and Ocean Pollution. Ann. Glob. Health 2020, 86, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puthusseri, R.M.; Nair, H.P.; Johny, T.K. Insights into the response of mangrove sediment microbiomes to heavy metal pollution: Ecological risk assessment and metagenomics perspectives. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 298, 113492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abreu, I.M.; Cordeiro, R.C.; Soares-Gomes, A. Ecological risk evaluation of sediment metals in a tropical Euthrophic Bay, Guanabara Bay, Southeast Atlantic. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2016, 109, 435–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Ishfaq, M.; Quintero, V.A.G.; Peng, D.; Lang, T.; Gao, C.; Zhou, H. Impact of elevated environmental pollutants on carbon storage in mangrove wetlands: A comprehensive review. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 178, 113830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udechukwu, B.E.; Ismail, A.; Zulkifli, S.Z. Distribution, mobility, and pollution assessment of Cd, Cu, Ni, Pb, Zn, and Fe in intertidal surface sediments of Sg. Puloh mangrove estuary, Malaysia. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 4242–4255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacFarlane, G.R.; Burchett, M.D. Cellular distribution of copper, lead and zinc in the grey mangrove, Avicennia marina (Forsk.) Vierh. Aquat. Bot. 2000, 68, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Li, X.; Bai, J. Effects of land use on the heavy metal pollution in mangrove sediments: Study on a whole island scale in Hainan, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 824, 153856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Sun, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Guo, M.; Hu, C.; Shui, B. Analysis of heavy metal sources and potential ecological risk assessment of mangroves in Aojiang Estuary. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 173, 113343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.M.; Huang, L. Influence of mangrove forestation on heavy metals accumulation and speciation in sediments and phytoremediation capacity of mangrove species of an artificial managed coastal Lagoon at Xiamen in China. Chem. Ecol. 2023, 39, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alongi, D.M.; Pfitzner, J.; Trott, L.A.; Tirendi, F.; Dixon, P.; Klumpp, D.W. Rapid sediment accumulation and microbial mineralization in forests of the mangrove Kandelia obovata in the Jiulongjiang Estuary, China. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2005, 63, 605–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.P. The Geochemical Characteristics of Nutrient Elements in River Water in Jiulongjiang Basin. Master’s Thesis, China University of Geosciences, Beijing, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Guo, R.; Zhang, N.; Yang, S.; Cao, W. Soil organic carbon storages and bacterial communities along a restored mangrove soil chronosequence in the Jiulong River Estuary: From tidal flats to mangrove afforestation. Fundam. Res. 2023, 3, 880–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Li, Z.; Du, B.; Wang, G.; Ding, Y. Bacterial communities in sediments of the shallow Lake Dongping in China. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2012, 112, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ELTurk, M.; Abdullah, R.; Zakaria, R.M.; Bakar, N.K.A. Heavy metal contamination in mangrove sediments in Klang estuary, Malaysia: Implication of risk assessment. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2019, 226, 106266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.J.; Zhu, Y.G.; Ding, H. Lead and cadmium in leaves of deciduous trees in Beijing, China: Development of a metal accumulation index (MAI). Environ. Pollut. 2007, 145, 387–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OriginPro, Version 2023b; OriginLab Corporation: Northampton, MA, USA, 2023.

- IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 24; IBM Corporation: Armonk, NY, USA, 2023.

- Yadav, K.K.; Gupta, N.; Prasad, S.; Malav, L.C.; Bhutto, J.K.; Ahmad, A.; Gacem, A.; Jeon, B.H.; Fallatah, A.M.; Asghar, B.H.; et al. An eco-sustainable approach towards heavy metals remediation by mangroves from the coastal environment: A critical review. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 188, 114569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, M.; Li, R.; Tam, N.F.Y.; Zan, Q. Effects of mangrove plant species on accumulation of heavy metals in sediment in a heavily polluted mangrove swamp in Pearl River Estuary, China. Environ. Geochem. Health 2019, 41, 175–189. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, L.; Li, R.; Liang, Z.; Hou, L.; Chen, J. Seasonal variations of cadmium (Cd) speciation and mobility in sediments from the Xizhi River basin, South China, based on passive sampling techniques and a thermodynamic chemical equilibrium model. Water Res. 2021, 207, 117751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyewo, O.A.; Adeniyi, A.; Bopape, M.F.; Onyango, M.S. Heavy metal mobility in surface water and soil, climate change, and soil interactions. In Climate Change and Soil Interactions; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 51–88. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Z.; Sun, X.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Li, X. Accumulation and tolerance of mangroves to heavy metals: A review. Curr. Pollut. Rep. 2017, 3, 302–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Mou, X.; Sun, W. Decomposition and heavy metal variations of the typical halophyte litters in coastal marshes of the Yellow River estuary, China. Chemosphere 2016, 147, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, T.; Tam, N.F.Y.; Hussain, M.; Ke, X.; Wei, J.; Fu, Y.; Li, M.; Huang, X.; Huang, S.; Zhou, H.; et al. Dynamics of heavy metals during the development and decomposition of leaves of Avicennia marina and Kandelia obovata in a subtropical mangrove swamp. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 855, 158700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borggaard, O.K.; Holm, P.E.; Strobel, B.W. Potential of dissolved organic matter (DOM) to extract As, Cd, Co, Cr, Cu, Ni, Pb and Zn from polluted soils: A review. Geoderma 2019, 343, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Laing, G. Dynamics of Heavy Metals in Reedbeds Along the Banks of the River Scheldt. Ph.D. Thesis, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, X.; Song, Z.; Wang, Y.P.; Wang, S.; Zhan, Z.W.; He, D. Heavy metal dynamics in riverine mangrove systems: A case study on content, migration, and enrichment in surface sediments, pore water, and plants in Zhanjiang, China. Mar. Environ. Res. 2025, 203, 106832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaushik, P.; Khandelwal, R.; Rawat, N.; Sharma, M.K. Environmental hazards of heavy metal pollution and toxicity: A review. Flora Fauna 2022, 28, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Nevel, L.; Mertens, J.; Demey, A.; De Schrijver, A.; De Neve, S.; Tack, F.M.; Verheyen, K. Metal and nutrient dynamics in decomposing tree litter on a metal contaminated site. Environ. Pollut. 2014, 189, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neel, C.; Soubrand-Colin, M.; Piquet-Pissaloux, A.; Bril, H. Mobility and bioavailability of Cr, Cu, Ni, Pb and Zn in a basaltic grassland: Comparison of selective extractions with quantitative approaches at different scales. Appl. Geochem. 2007, 22, 724–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, R.; Mandal, S.K.; González, A.G.; Pokrovsky, O.S.; Jana, T.K. Storage and recycling of major and trace element in mangroves. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 780, 146379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Lin, H.; Du, D.; Li, G.; Alam, O.; Cheng, Z.; Li, J. Remediation of heavy metals polluted soil environment: A critical review on biological approaches. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 284, 116883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caporale, A.G.; Violante, A. Chemical processes affecting the mobility of heavy metals and metalloids in soil environments. Curr. Pollut. Rep. 2016, 2, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, W.; Lacerda, L.D. Overview of the biogeochemical controls and concerns with trace metal accumulation in mangrove sediments. In Environmental Geochemistry in Tropical and Subtropical Environments; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; pp. 319–334. [Google Scholar]

- MacFarlane, G.R.; Pulkownik, A.; Burchett, M.D. Accumulation and distribution of heavy metals in the grey mangrove, Avicennia marina (Forsk.) Vierh.: Biological indication potential. Environ. Pollut. 2003, 123, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, S.; Shahid, M.; Niazi, N.K.; Rafiq, M.; Bakhat, H.F.; Imran, M.; Abbas, T.; Bibi, I.; Dumat, C. Arsenic behaviour in soil-plant system: Biogeochemical reactions and chemical speciation influences. In Enhancing Cleanup of Environmental Pollutants: Volume 2: Non-Biological Approaches; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 97–140. [Google Scholar]

- Bhutia, T.; Nasnodkar, M.R.; Nayak, G.N. Speciation of metals in sediments and their bioaccumulation by edible bivalves (Cassosstrea spp. and Polymesoda spp.) in the aquatic bodies of Goa, west coast of India. Arab. J. Geosci. 2023, 16, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Li, G.; Jin, N.; Zhang, D. Synergistic/antagonistic toxicity characterization and source-apportionment of heavy metals and organophosphorus pesticides by the biospectroscopy-bioreporter-coupling approach. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 905, 167057. [Google Scholar]

- Narwal, N.; Kakakhel, M.A.; Katyal, D.; Yadav, S.; Rose, P.K.; Rene, E.R.; Rakib, M.R.J.; Khoo, K.S.; Kataria, N. Interactions Between Microplastic and Heavy Metals in the Aquatic Environment: Implications for Toxicity and Mitigation Strategies. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2024, 235, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Gao, L.; Duan, P.; Wu, H.; Li, M. Evaluating combined toxicity of binary heavy metals to the cyanobacterium Microcystis: A theoretical non-linear combined toxicity assessment method. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 187, 109809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.-M.; Wang, L.; Chen, L.; Tian, L.-J.; Zhu, T.-T.; Wu, Q.-Z.; Hu, Y.-R.; Zheng, L.-R.; Li, W.-W. AQDS Activates Extracellular Synergistic Biodetoxification of Copper and Selenite via Altering the Coordination Environment of Outer-Membrane Proteins. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 13786–13797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Cobbina, S.J.; Mao, G.; Xu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, L. A review of toxicity and mechanisms of individual and mixtures of heavy metals in the environment. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 8244–8259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, H.X. Studies on Dynamics of Heavy Metals with Decomposition of Litter Fall in Mangrove Wetland at Jiulongjiang River Estuary. Master’s Thesis, Xiamen University, Xiamen, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Miranda, L.S.; Ayoko, G.A.; Egodawatta, P.; Goonetilleke, A. Adsorption-desorption behavior of heavy metals in aquatic environments: Influence of sediment, water and metal ionic properties. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 421, 126743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwiatkowska-Malina, J. Functions of organic matter in polluted soils: The effect of organic amendments on phytoavailability of heavy metals. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2018, 123, 542–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Mou, X.; Zhang, D.; Sun, W.; Hu, X.; Tian, L. Impacts of burial by sediment on decomposition and heavy metal concentrations of Suaeda salsa in intertidal zone of the Yellow River estuary, China. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017, 116, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Soriano, M.C.; Jimenez-Lopez, J.C. Effects of soil water content and organic matter addition on the speciation and bioavailability of heavy metals. Sci. Total Environ. 2012, 423, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Mou, X. Effects of sediment burial disturbance on macro and microelement dynamics in decomposing litter of Phragmites australis in the coastal marsh of the Yellow River estuary, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 5189–5202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, D.; Lu, Z.; Ma, L. Decomposition and variation in carbon and nitrogen of leaf litter mixtures in a subtropical mangrove forest. Forests 2024, 15, 672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, R.R.; Aspandiar, M.F.; Noble, R.R. A review of metal transfer mechanisms through transported cover with emphasis on the vadose zone within the Australian regolith. Ore Geol. Rev. 2016, 73, 394–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, K.; Yang, W.; Peng, Y.; Zhang, C.; Huang, C.; Wu, F. Chromium, cadmium, and lead dynamics during winter foliar litter decomposition in an alpine forest river. Arct. Antarct. Alp. Res. 2016, 48, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, P.; Caçador, I.; Vale, C.; Caetano, M.; Costa, A.L. Decomposition of belowground litter and metal dynamics in salt marshes (Tagus Estuary, Portugal). Sci. Total Environ. 2007, 380, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artemkina, N.A.; Orlova, M.A.; Lukina, N.V. Spatial variation in the concentration of phenolic compounds and nutritional elements in the needles of spruce in northern taiga forests. Contemp. Probl. Ecol. 2019, 12, 769–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Fei, J.; Sun, C.; Li, Z.H.; Cheng, H. The inputs of autochthonous organic carbon driven by mangroves reduce metal mobility and bioavailability in intertidal regions. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 931, 172964. [Google Scholar]

- Wuana, R.A.; Okieimen, F.E. Heavy metals in contaminated soils: A review of sources, chemistry, risks and best available strategies for remediation. ISRN Ecol. 2011, 2011, 402647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment Group | Abbreviation | Weight of Samples (g) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single species treatments | Kandelia obovata | KO | KO = 36 | |

| Avicennia marina | AM | AM = 36 | ||

| Mixed species treatments | Kandelia obovata:Avicennia marina = 1:2 | KO:AM = 1:2 | KO = 12 | AM = 24 |

| Kandelia obovata:Avicennia marina = 1:1 | KO:AM = 1:1 | KO = 18 | AM = 18 | |

| Kandelia obovata:Avicennia marina = 2:1 | KO:AM = 2:1 | KO = 24 | AM = 12 | |

| Heavy Metal | Season (S) | Treatment (T) | Decomposition Time (D) | S × T | S × D | T × D |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V | F = 54.91 p < 0.001 | F = 4.33 p < 0.05 | F = 11.30 p < 0.001 | F = 2.59 p = n.s. | F = 5.21 p < 0.001 | F = 2.04 p < 0.05 |

| Cr | F = 1.73 p = n.s. | F = 16.11 p < 0.001 | F = 7.78 p < 0.001 | F = 1.60 p = n.s. | F = 8.57 p < 0.001 | F = 1.11 p = n.s. |

| Ni | F = 0.02 p = n.s. | F = 14.97 p < 0.001 | F = 5.48 p < 0.001 | F = 0.91 p = n.s. | F = 5.69 p < 0.001 | F = 2.31 p < 0.05 |

| Cu | F = 2.72 p = n.s. | F = 20.94 p < 0.001 | F = 38.10 p < 0.001 | F = 6.85 p < 0.01 | F = 14.82 p < 0.001 | F = 6.15 p < 0.001 |

| Zn | F = 0.76 p = n.s. | F = 3.04 p = n.s. | F = 19.10 p < 0.001 | F = 0.29 p = n.s. | F = 9.67 p < 0.001 | F = 0.55 p = n.s. |

| As | F = 31.33 p < 0.001 | F = 10.42 p < 0.001 | F = 44.70 p < 0.001 | F = 1.50 p = n.s. | F = 22.43 p < 0.001 | F = 2.11 p = n.s. |

| Se | F = 35.62 p < 0.001 | F = 12.74 p < 0.001 | F = 47.76 p < 0.001 | F = 0.21 p = n.s. | F = 19.70 p < 0.001 | F = 2.07 p = n.s. |

| Cd | F = 22.21 p < 0.001 | F = 12.96 p < 0.001 | F = 39.61 p < 0.001 | F = 0.34 p = n.s. | F = 10.26 p < 0.001 | F = 3.88 p < 0.05 |

| Group | V | Cr | Ni | Cu | Zn | As | Se | Cd | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KO:AM = 1:2 | C/M | −0.804 ** | −0.394 | −0.614 * | −0.681 * | −0.963 ** | −0.705 ** | −0.690 ** | −0.645 * |

| C/N | −0.605 * | −0.087 | −0.197 | −0.24 | −0.666 * | −0.399 | −0.381 | −0.604 * | |

| KO:AM = 1:1 | C/M | −0.772 ** | −0.620 * | −0.631 * | −0.694 ** | −0.930 ** | −0.746 ** | −0.724 ** | −0.635 * |

| C/N | −0.449 | −0.137 | −0.034 | −0.088 | −0.483 | −0.319 | −0.296 | −0.603 * | |

| KO:AM = 2:1 | C/M | −0.686 ** | −0.667 * | −0.647 * | −0.508 | −0.953 ** | −0.704 ** | −0.646 * | −0.634 * |

| C/N | −0.378 | −0.327 | −0.367 | 0.021 | −0.608 * | −0.345 | −0.200 | −0.485 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Xu, X.; Wan, Y.; Lu, Z.; Li, D.; Ma, L. Dynamic Shifts of Heavy Metals During Mixed Leaf Litter Decomposition in a Subtropical Mangrove. Plants 2026, 15, 478. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15030478

Xu X, Wan Y, Lu Z, Li D, Ma L. Dynamic Shifts of Heavy Metals During Mixed Leaf Litter Decomposition in a Subtropical Mangrove. Plants. 2026; 15(3):478. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15030478

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Xinlei, Yuxuan Wan, Zhiqiang Lu, Danyang Li, and Li Ma. 2026. "Dynamic Shifts of Heavy Metals During Mixed Leaf Litter Decomposition in a Subtropical Mangrove" Plants 15, no. 3: 478. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15030478

APA StyleXu, X., Wan, Y., Lu, Z., Li, D., & Ma, L. (2026). Dynamic Shifts of Heavy Metals During Mixed Leaf Litter Decomposition in a Subtropical Mangrove. Plants, 15(3), 478. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15030478