The Maize WRKY Transcription Factor ZmWRKY4 Confers Lead Tolerance by Regulating ZmCAT1 Expression

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

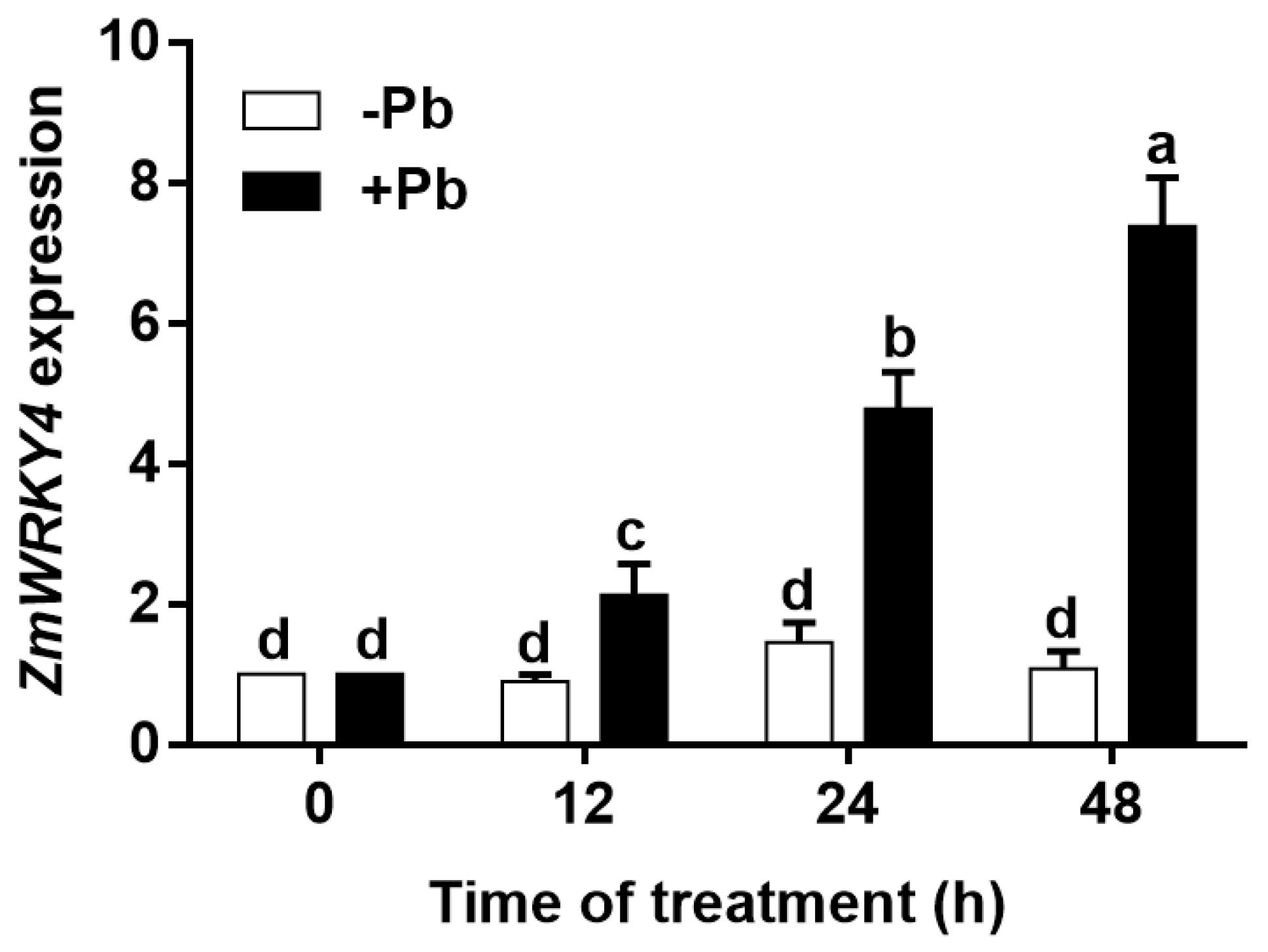

2.1. ZmWRKY4 Is Induced by Pb Stress

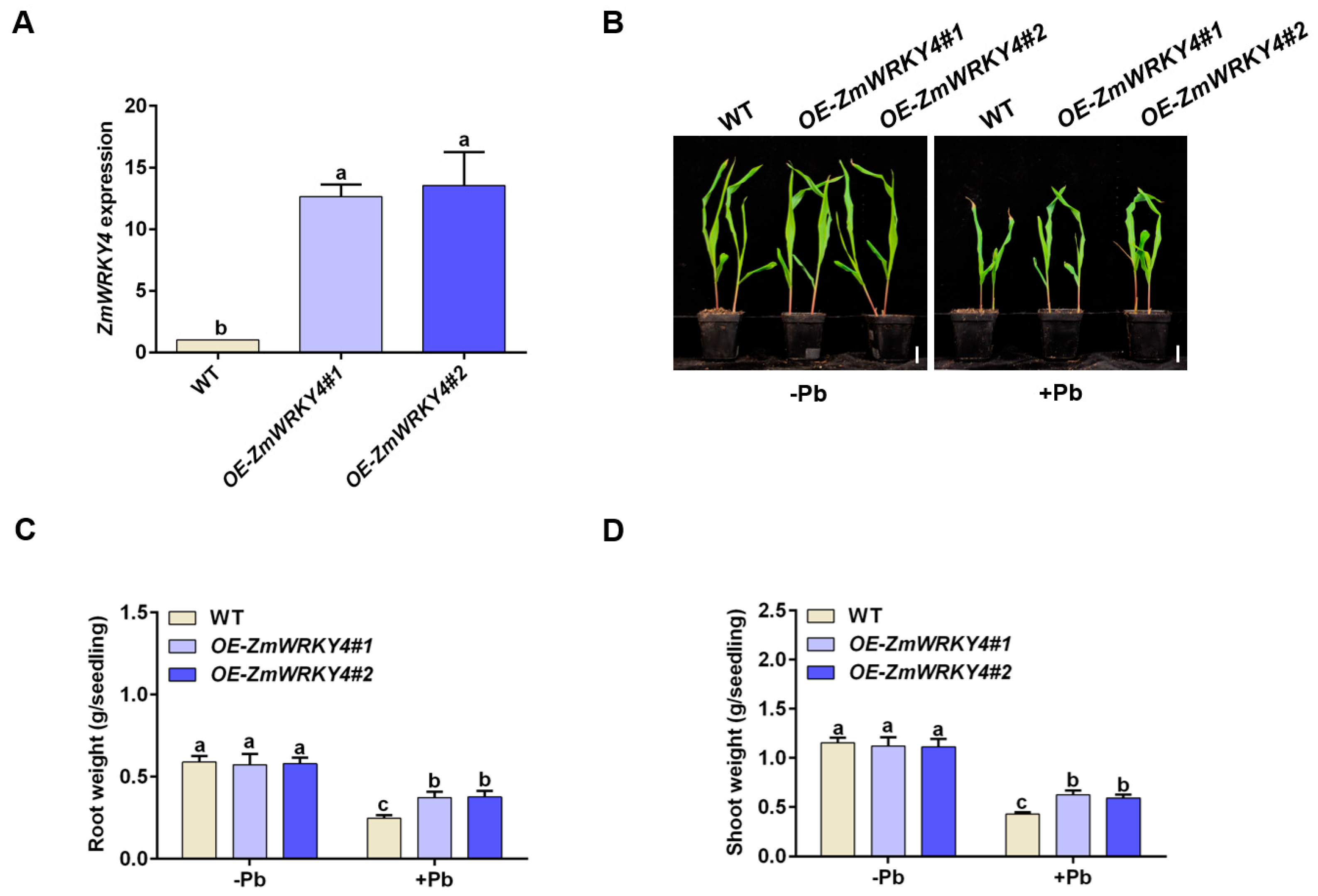

2.2. ZmWRKY4 Positively Regulates Pb Stress Tolerance in Maize

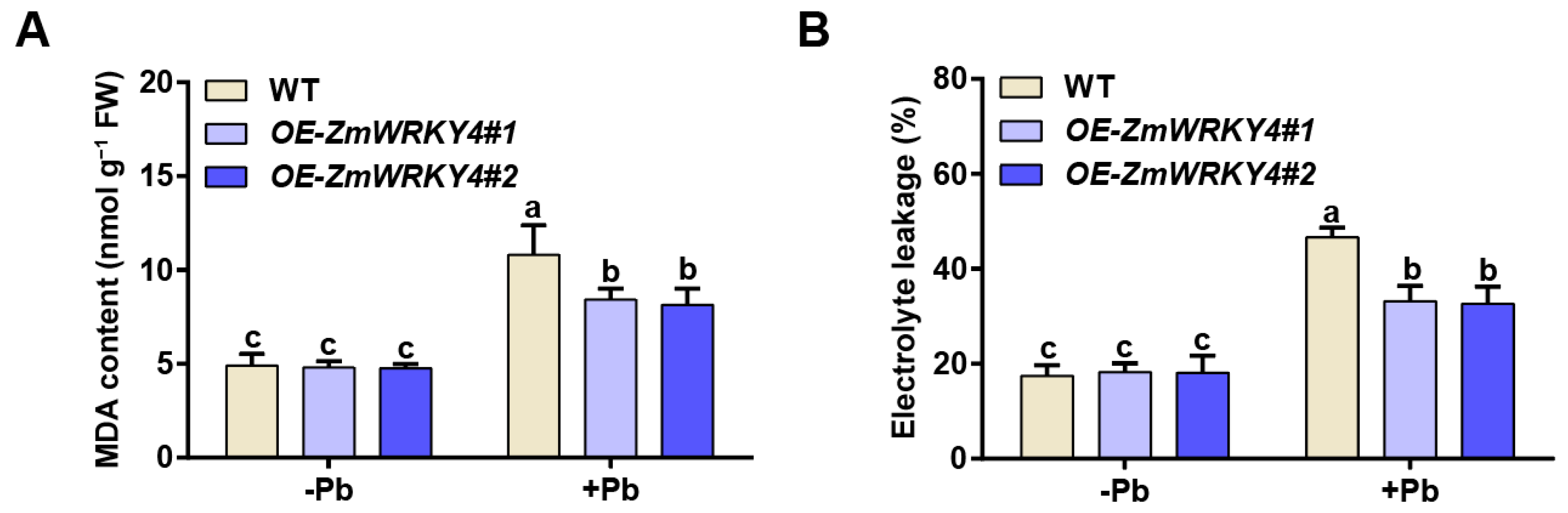

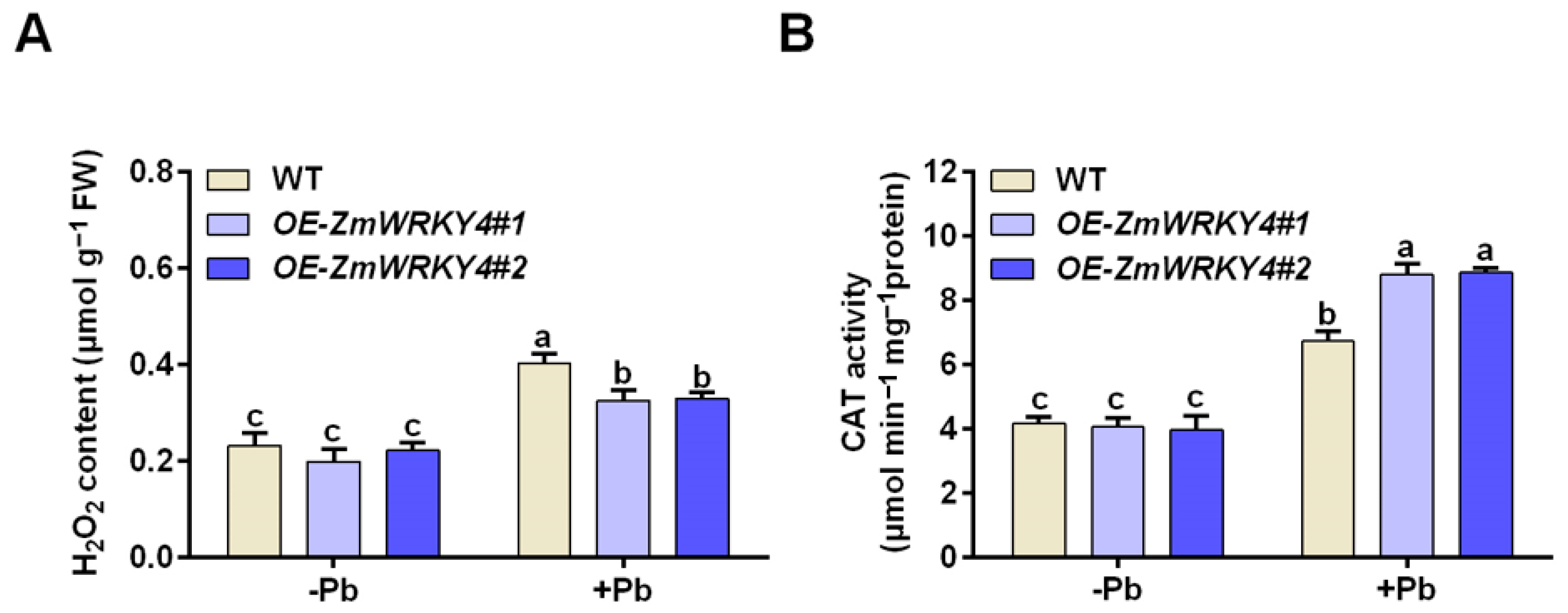

2.3. ZmWRKY4 Enhances the Activity of CAT Under Pb Stress

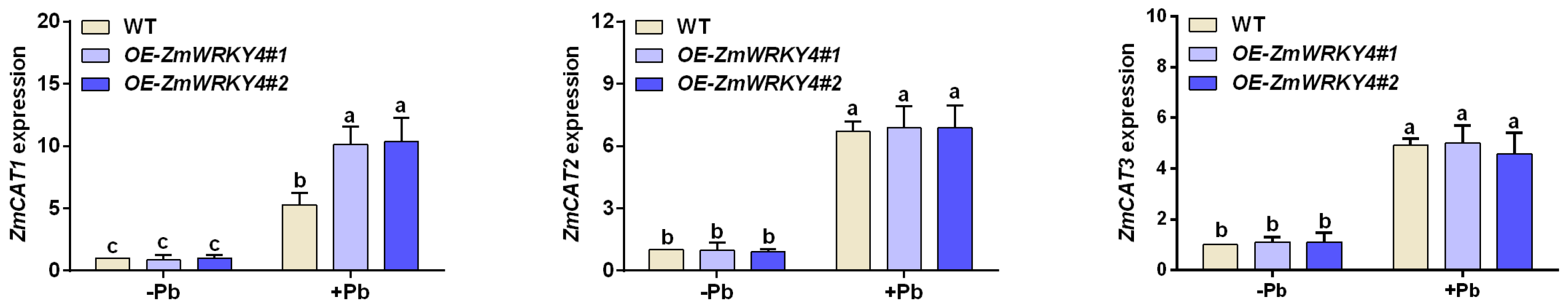

2.4. ZmWRKY4 Positively Regulates ZmCAT1 Under Pb Stress

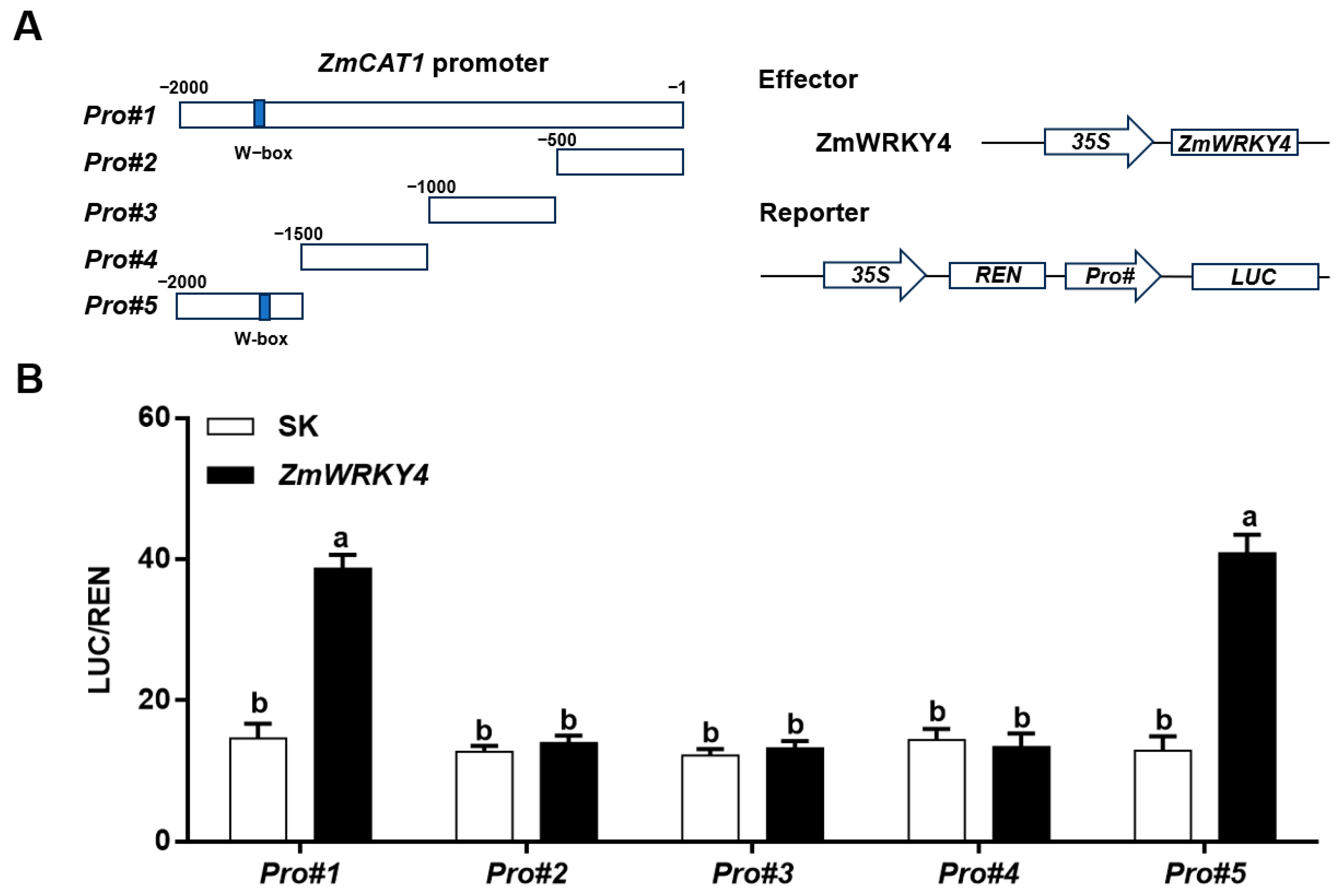

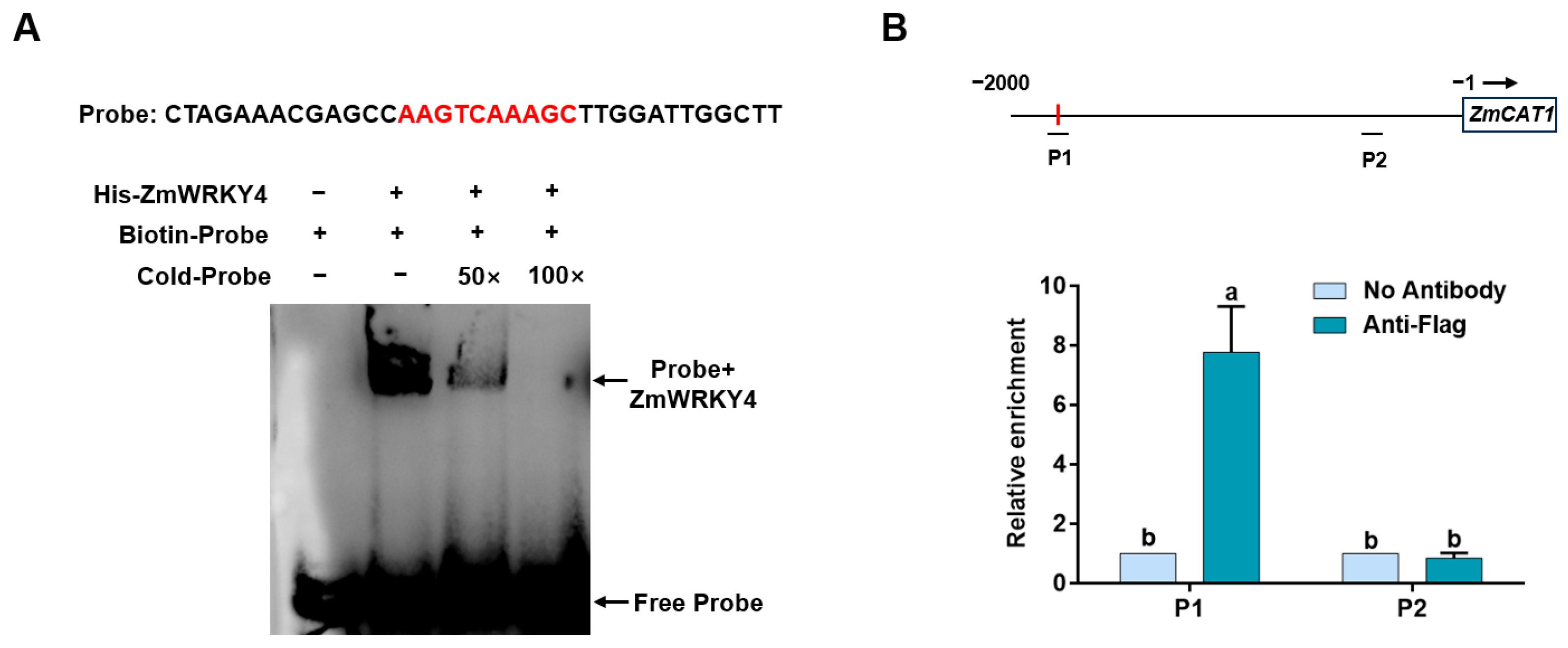

2.5. ZmWRKY4 Directly Binds to the ZmCAT1 Promoter In Vivo and In Vitro

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials

4.2. Generation of OE-ZmWRKY4 Transgenic Maize

4.3. Real Time Quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

4.4. Determination of MDA and Electrolyte Leakage

4.5. Determination of H2O2 Conent

4.6. Determination of CAT Activity

4.7. Dual-Luciferase Reporter Analysis

4.8. Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA)

4.9. Chromatin Immunoprecipitation-Quantitative PCR (ChIP-qPCR)

4.10. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, X.; Zhao, B.; Ma, X.; Jin, X.; Chen, S.; Wang, P.; Zhongrong, G.; Wu, X.; Zhang, H. Combining transcriptome and metabolome analyses to reveal the response of maize roots to Pb stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 217, 109265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; An, R.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, C.; Li, Z.; Zou, C.; Yang, C.; Pan, G.; Lübberstedt, T.; Shen, Y. Effects of ZmHIPP on lead tolerance in maize seedlings: Novel ideas for soil bioremediation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 430, 128457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, P.; Zhou, X.; Sang, M.; Li, M.; Li, Q.; Chen, Z.; Zou, C.; Ma, L.; Shen, Y. PIP family-based association studies uncover ZmPIP1; 6 involved in Pb accumulation and water absorption in maize roots. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 214, 108974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.N.; Dushenkov, V.; Motto, H.; Raskin, I. Phytoextraction: The use of plants to remove heavy metals from soils. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1995, 29, 1232–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, Z.; Xuan, Z.; Wu, C.; Cheng, Y.; Xu, C.; Ma, X.; Wang, D. Effects of selenium on the AsA-GSH system and photosynthesis of pakchoi (Brassica chinensis L.) under lead stress. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2022, 22, 5111–5122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obroucheva, N.; Bystrova, E.; Ivanov, V.; Antipova, O.; Seregin, I. Root growth responses to lead in young maize seedlings. Plant Soil 1998, 200, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Ren, Y.; Han, C.; Zhu, W.; Gu, J.; He, J. Application of exogenous glycinebetaine alleviates lead toxicity in pakchoi (Brassica chinensis L.) by promoting antioxidant enzymes and suppressing Pb accumulation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 25568–25580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Li, B.; Wang, Y.; Xu, J.; Li, W.; Chen, Z.H.; Mou, W.; Xue, D. WRKY Transcription Factors in Rice: Key Regulators Orchestrating Development and Stress Resilience. Plant Cell Environ. 2025, 48, 8388–8406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eulgem, T.; Rushton, P.J.; Robatzek, S.; Somssich, I.E. The WRKY superfamily of plant transcription factors. Trends Plant Sci. 2000, 5, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Hu, Y.; Vannozzi, A.; Wu, K.; Cai, H.; Qin, Y.; Mullis, A.; Lin, Z.; Zhang, L. The WRKY transcription factor family in model plants and crops. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2017, 36, 311–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Hu, L. WRKY transcription factor responses and tolerance to abiotic stresses in plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Chen, W.; Xu, Z.; Chen, M.; Yu, D. Functions of WRKYs in plant growth and development. Trends Plant Sci. 2023, 28, 630–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lippok, B.; Birkenbihl, R.P.; Rivory, G.; Brümmer, J.; Schmelzer, E.; Logemann, E.; Somssich, I.E. Expression of AtWRKY33 encoding a pathogen-or PAMP-responsive WRKY transcription factor is regulated by a composite DNA motif containing W box elements. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2007, 20, 420–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, X.; Meng, X.; Zhang, J.; Xia, M.; Cao, S.; Tang, X.; Fan, T. AtWRKY1 negatively regulates the response of Arabidopsis thaliana to Pst. DC3000. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 166, 799–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.J.; Yan, J.Y.; Li, C.X.; Li, G.X.; Wu, Y.R.; Zheng, S.J. Transcription factor WRKY 46 modulates the development of Arabidopsis lateral roots in osmotic/salt stress conditions via regulation of ABA signaling and auxin homeostasis. Plant J. 2015, 84, 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhao, R.; Huang, K.; Huang, S.; Wang, H.; Wei, Z.; Li, Z.; Bian, M.; Jiang, W.; Wu, T. The OsWRKY63–OsWRKY76–OsDREB1B module regulates chilling tolerance in rice. Plant J. 2022, 112, 383–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Li, J.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, A. ZmWRKY104 positively regulates salt tolerance by modulating ZmSOD4 expression in maize. Crop J. 2022, 10, 555–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, Y.; Yan, X.; Huang, Y.; Han, Y.; Zhang, C.; Ren, Y.; Fan, T.; Xiao, F.; Liu, Y.; Cao, S. The WRKY transcription factor, WRKY13, activates PDR8 expression to positively regulate cadmium tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Environ. 2019, 42, 891–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, L.; Hou, Y.; Sun, Y.; Chen, X.; Wang, G.; Wang, H.; Zhu, B.; Du, X. The maize WRKY transcription factor ZmWRKY64 confers cadmium tolerance in Arabidopsis and maize (Zea mays L.). Plant Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, C.; Cheng, D.; Zhang, G.; Zhu, D.; Chen, Y.; Tan, M. The role of ZmWRKY4 in regulating maize antioxidant defense under cadmium stress. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017, 482, 1504–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.Z.; Wang, Z.Q.; Yokosho, K.; Ding, B.; Fan, W.; Gong, Q.Q.; Li, G.X.; Wu, Y.R.; Yang, J.L.; Ma, J.F. Transcription factor WRKY 22 promotes aluminum tolerance via activation of Os FRDL 4 expression and enhancement of citrate secretion in rice (Oryza sativa). New Phytol. 2018, 219, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; An, R.; Yan, J.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, N.; Xi, N.; Yu, H.; Zou, C.; Gao, S.; Yuan, G. Association studies of genes in a Pb response-associated network in maize (Zea mays L.) reveal that ZmPIP2; 5 is involved in Pb tolerance. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2023, 195, 300–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, F.; Liang, Y.; Sang, M.; Zhao, G.; Song, J.; Liu, P.; Zou, C.; Chen, Z.; Ma, L.; Shen, Y. Complex regulatory network of ZmbZIP54-mediated Pb tolerance in maize. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 224, 109945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Jiang, L.; Wang, C.; Liu, P.; Ma, L.; Zou, C.; Pan, G.; Shen, Y. Combined genome-wide association study and gene co-expression network analysis identified ZmAKINβγ1 involved in lead tolerance and accumulation in maize seedlings. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 226, 1374–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, F.; Zhang, N.; Ma, L.; An, L.; Zhou, X.; Zou, C.; Yang, C.; Pan, G.; Lübberstedt, T.; Shen, Y. ZmbZIP54 and ZmFDX5 cooperatively regulate maize seedling tolerance to lead by mediating ZmPRP1 transcription. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 224, 621–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Y.; Han, T.; Xiang, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhang, A. The transcription factor ZmNAC84 increases maize salt tolerance by regulating ZmCAT1 expression. Crop J. 2024, 12, 1344–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Li, M.; Wang, H.; Zhu, B.; Gu, L.; Du, X.; Ren, M. TaWRKY70 positively regulates TaCAT5 enhanced Cd tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2021, 190, 104591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, W.; Ji, M.; Dong, J.; Lai, D.; Yu, W.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, Y. RsWRKY75 promotes ROS scavenging and cadmium efflux via activating the transcription of RsAPX1 and RsPDR8 in radish (Raphanus sativus L.). Plant Cell Rep. 2025, 44, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Cheng, Y.; Cai, Z.; Nian, H.; Ma, Q. GmWRKY21, a soybean WRKY transcription factor gene, enhances the tolerance to aluminum stress in Arabidopsis thaliana. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 833326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, F.; Lin, J.; Chen, Y.; Li, G.X.; Guan, D.; Zheng, S.J.; He, S. A feedback loop between CaWRKY41 and H2O2 coordinates the response to Ralstonia solanacearum and excess cadmium in pepper. J. Exp. Bot. 2019, 79, 1581–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; John Martin, J.J.; Li, R.; Zeng, X.; Wu, Q.; Li, Q.; Fu, D.; Li, X.; Liu, X.; Ye, J. Catalase (CAT) Gene Family in Oil Palm (Elaeis guineensis Jacq.): Genome-Wide Identification, Analysis, and Expression Profile in Response to Abiotic Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, L.; Yang, Y.; Jiang, L.; Liu, S. The catalase gene family in cucumber: Genome-wide identification and organization. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2016, 39, 408–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, W.; Ye, Q.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, L.; Liu, J.; Hu, X.; Guo, D.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Z. Analysis of CAT gene family and functional identification of OsCAT3 in rice. Genes 2023, 14, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, T.; Wang, P.; Li, H.; Zhao, Y.; Lu, Y.; Dai, P.; Ren, T.; Wang, X.; Li, X.; Shao, Q. The Arabidopsis catalase triple mutant reveals important roles of catalases and peroxisome-derived signaling in plant development. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2018, 60, 591–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willekens, H.; Villarroel, R.; Van Montagu, M.; Inzé, D.; Van Camp, W. Molecular identification of catalases from Nicotiana plumbaginifolia (L.). FEBS Lett. 1994, 352, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tounsi, S.; Kamoun, Y.; Feki, K.; Jemli, S.; Saïdi, M.N.; Ziadi, H.; Alcon, C.; Brini, F. Localization and expression analysis of a novel catalase from Triticum monococcum TmCAT1 involved in response to different environmental stresses. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2019, 139, 366–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, D.; Tang, H.; Li, H.; Zhang, X.; Dong, S.; Zhang, L.; Yang, L. Identification and analysis of the catalase gene family response to abiotic stress in Nicotiana tabacum L. Agronomy 2023, 13, 936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhamdi, A.; Queval, G.; Chaouch, S.; Vanderauwera, S.; Van Breusegem, F.; Noctor, G. Catalase function in plants: A focus on Arabidopsis mutants as stress-mimic models. J. Exp. Bot. 2010, 61, 4197–4220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.Y.; Wang, P.C.; Chen, J.; Song, C.P. Comprehensive functional analysis of the catalase gene family in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2008, 50, 1318–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Liang, G.; Yang, S.; Yu, D. Arabidopsis WRKY57 functions as a node of convergence for jasmonic acid–and auxin-mediated signaling in jasmonic acid–induced leaf senescence. Plant Cell 2014, 26, 230–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Fan, T.; Zhu, X.; Wu, X.; Ouyang, J.; Jiang, L.; Cao, S. WRKY12 represses GSH1 expression to negatively regulate cadmium tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Mol. Biol. 2019, 99, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, S.; Liu, X.; Wang, R.; Chen, W.; Suo, J.; Yan, J.; Wu, J. Agrobacterium-mediated transient expression in Torreya grandis cones: A simple and rapid tool for gene expression and functional gene assay. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 338, 113664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, T.; Wang, L.; Jiang, Q.; Wang, M.; Wang, C.; Wang, M.; Zhao, J.; Tian, S.; Liu, C.; Yang, Y. Extracellular adenosine triphosphate (eATP) alleviates phytotoxicity of nanoplastics in maize (Zea mays L.) plants. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2024, 226, 105879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wang, M.; Fang, L. BASIC PENTACYSTEINE2 negatively regulates osmotic stress tolerance by modulating LEA4-5 expression in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 168, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Yang, Y.; Ma, Z.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, X.; Chen, Z.; Cui, G.; Yin, X. Integrated physiological, transcriptomic and metabolomic analysis of the response of Trifolium pratense L. to Pb toxicity. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 436, 129128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Yan, J.; Chen, J.; Wang, T.; Li, X.; Wang, S.; Wang, R.; Liu, Y.; Yan, J.; Wu, J. The TgIAA7-TgARF10-TgProDH1 module regulates waterlogging-mediated proline accumulation in the gymnosperm Torreya grandis. Plant Physiol. 2025, 199, kiaf619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Liu, Z.; Wang, T.; Wang, R.; Wang, S.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; Yan, J.; Wu, J. TgRAV1–TgWRKY74–TgACS13 module fine-tunes ethylene biosynthesis to modulate waterlogging-induced root vitality in the gymnosperm Torreya grandis. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, L.; Liu, M.; Bi, W.; Li, S.; Chen, C.; Jing, Y.; Zhang, X.; Han, T. The Maize WRKY Transcription Factor ZmWRKY4 Confers Lead Tolerance by Regulating ZmCAT1 Expression. Plants 2026, 15, 394. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15030394

Wang L, Liu M, Bi W, Li S, Chen C, Jing Y, Zhang X, Han T. The Maize WRKY Transcription Factor ZmWRKY4 Confers Lead Tolerance by Regulating ZmCAT1 Expression. Plants. 2026; 15(3):394. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15030394

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Long, Meiying Liu, Wenfei Bi, Su Li, Chang Chen, Yang Jing, Xiong Zhang, and Tong Han. 2026. "The Maize WRKY Transcription Factor ZmWRKY4 Confers Lead Tolerance by Regulating ZmCAT1 Expression" Plants 15, no. 3: 394. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15030394

APA StyleWang, L., Liu, M., Bi, W., Li, S., Chen, C., Jing, Y., Zhang, X., & Han, T. (2026). The Maize WRKY Transcription Factor ZmWRKY4 Confers Lead Tolerance by Regulating ZmCAT1 Expression. Plants, 15(3), 394. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15030394