Evaluating the Sustainability of High-Dose Sewage Sludge Application in Fertilizing Szarvasi-1 Energy Grass Plantations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Dry Biomass Yield of the Szarvasi-1 Energy Grass

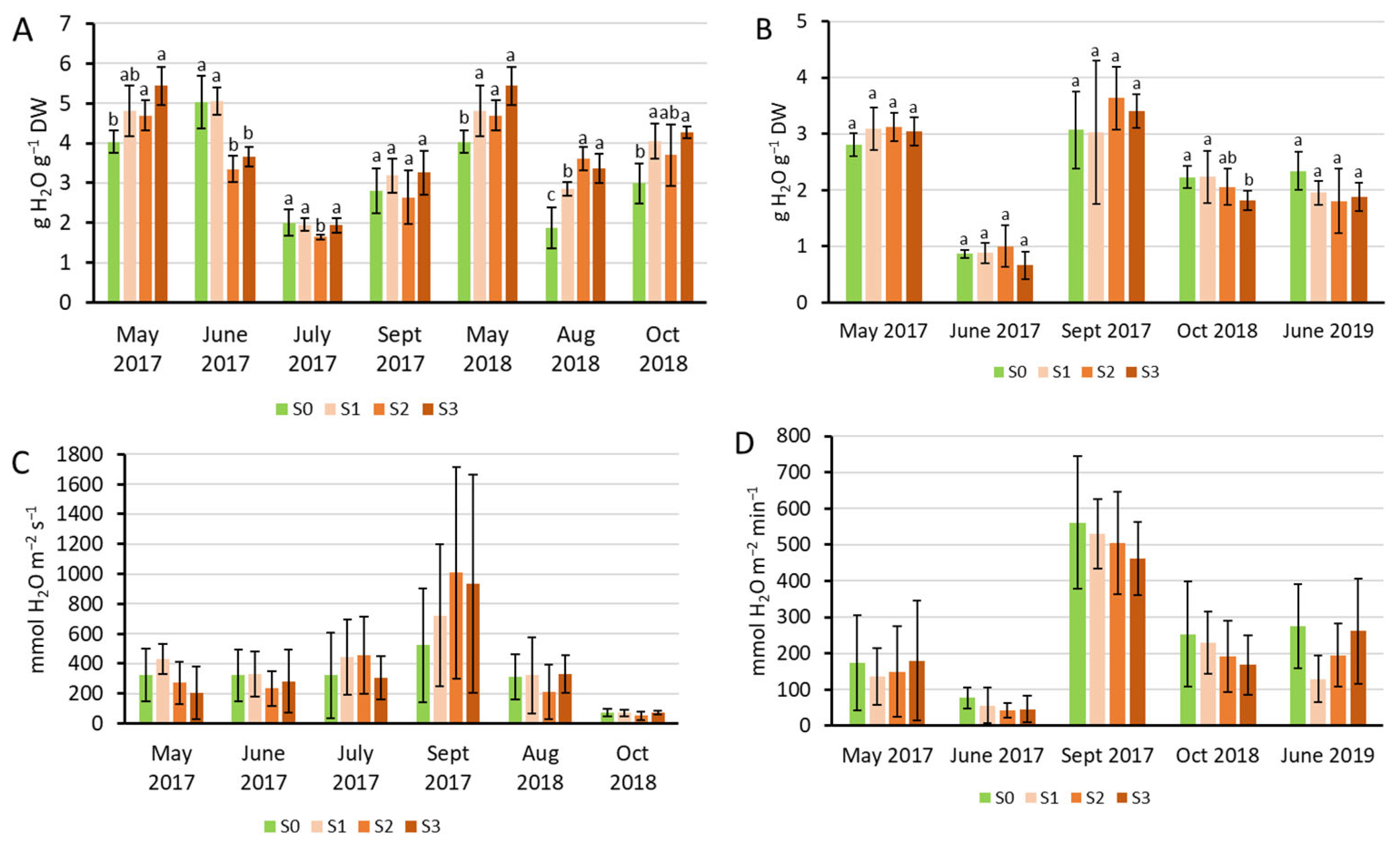

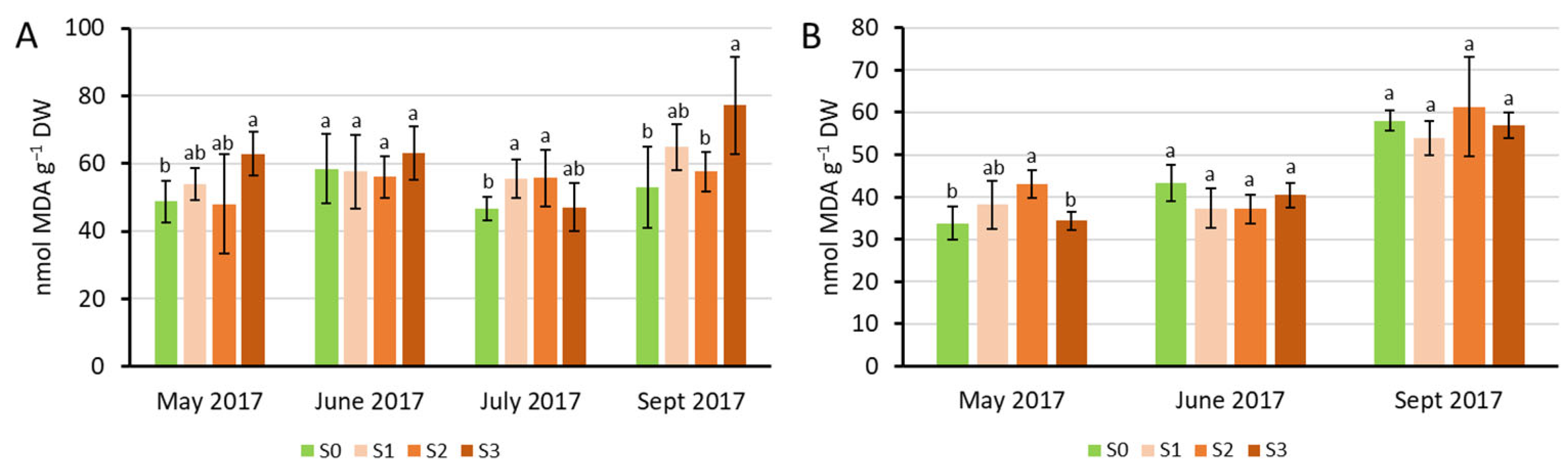

2.2. Physiological Characterization of the Plants Under Sewage Sludge Treatments

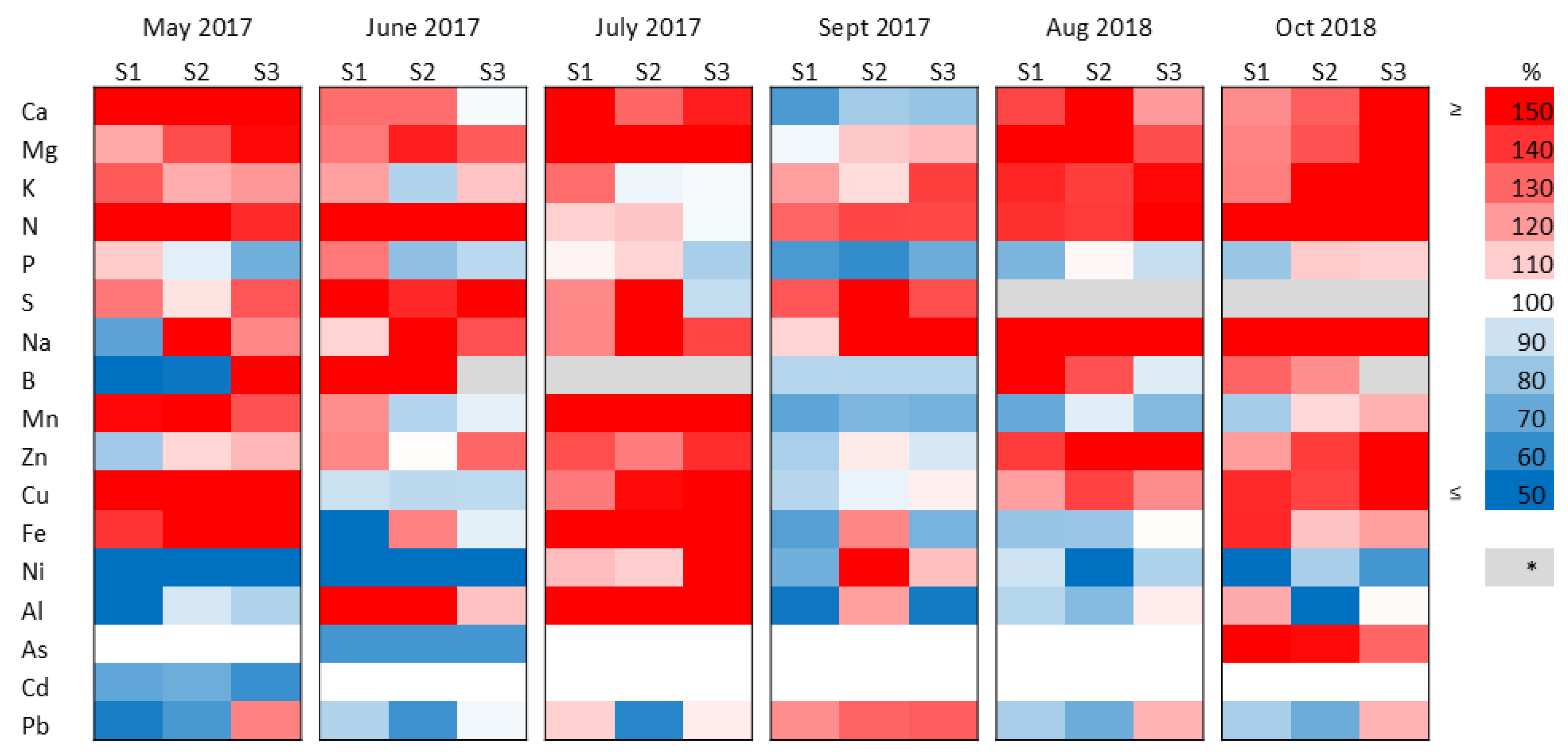

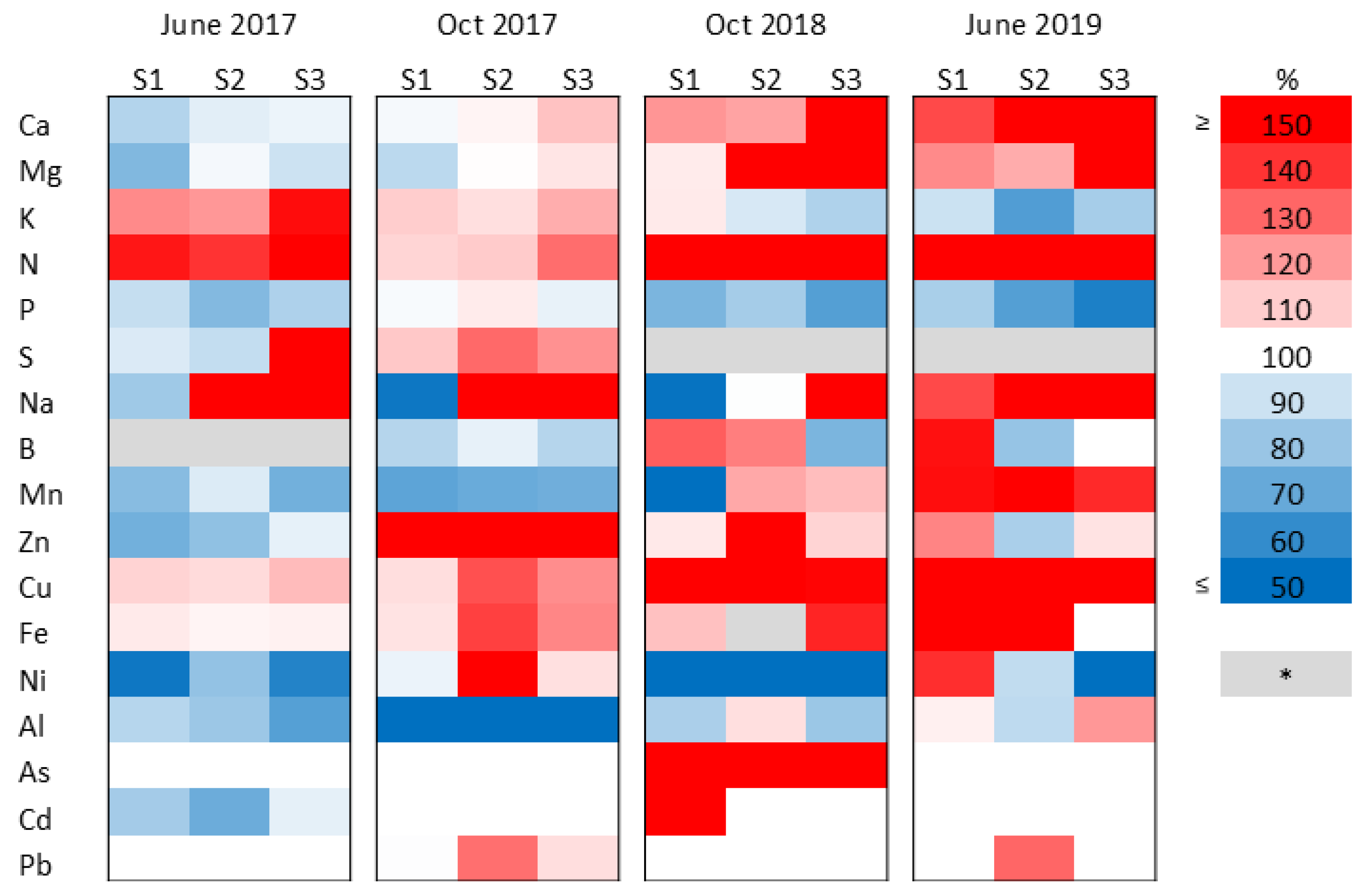

2.3. Changes in the Element Composition of the Plants Under Sewage Sludge Treatments

2.4. Nutrient and Trace-Element Balance

3. Discussion

3.1. Yield and Physiological Characteristics

3.2. Element Composition of Szarvasi-1 and the Sustainability of Sewage Sludge Applications

4. Materials and Methods

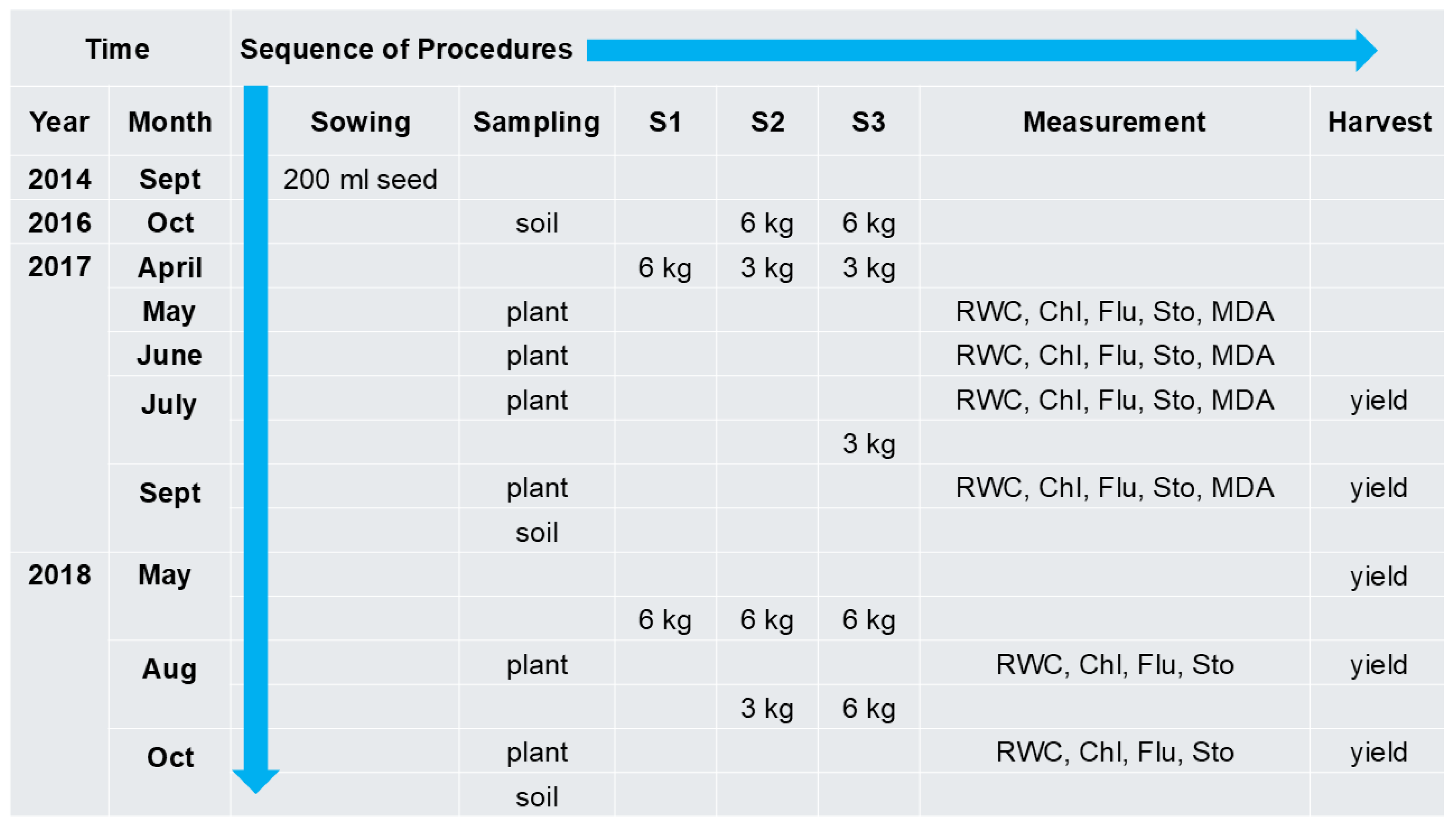

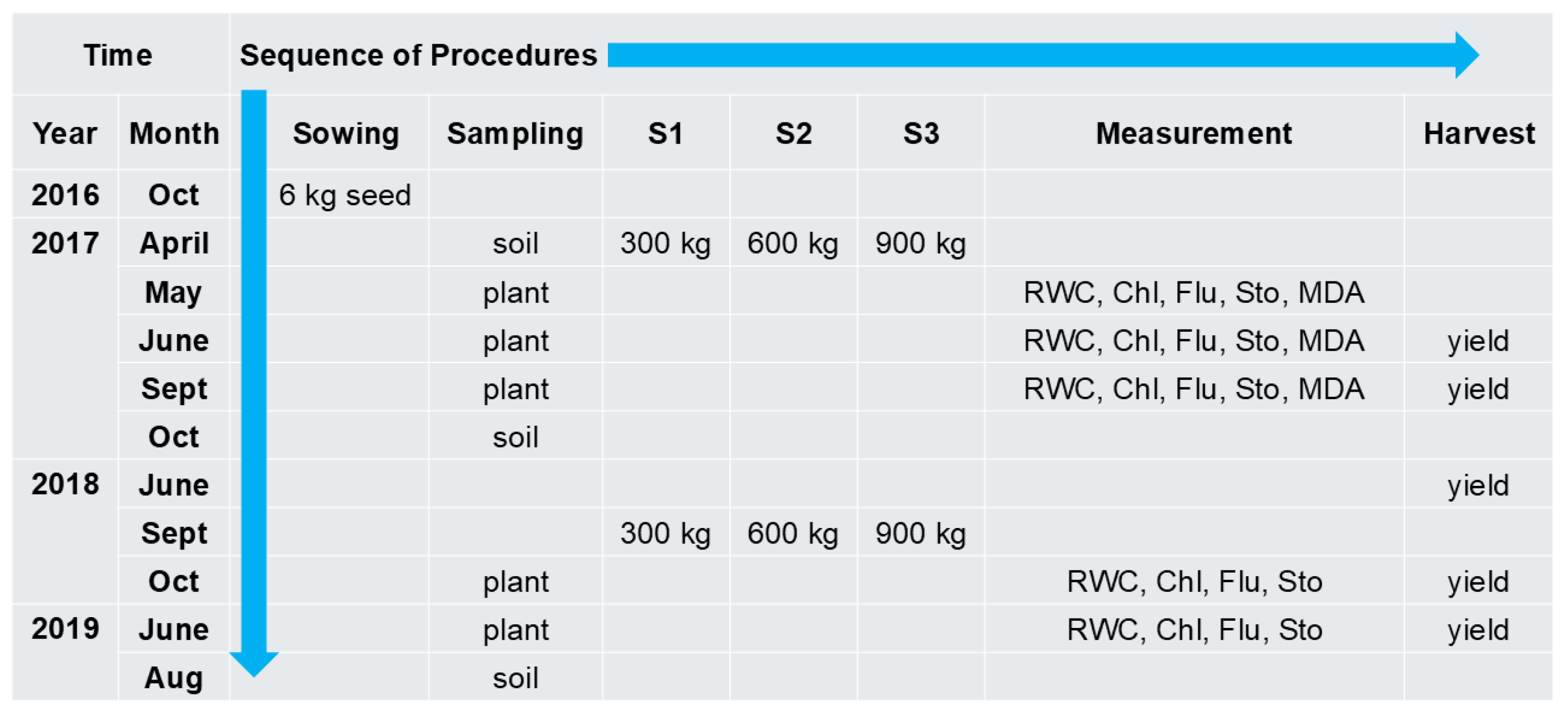

4.1. Soil, Plant Material, and Experimental Design

4.2. Relative Water Content and Yield Assessment

4.3. Chlorophyll Content

4.4. Stomatal Conductance

4.5. Malondialdehyde Concentration

4.6. Chlorophyll a Fluorescence Induction

4.7. Measurement of Element Concentrations and Calculations

4.8. Statistical Treatment

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Epstein, E. Land Application of Sewage Sludge and Biosolids; Lewis Publishers: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2002; p. 216. [Google Scholar]

- Fytili, D.; Zabaniotou, A. Utilization of sewage sludge in EU application of old and new methods—A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2008, 12, 116–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurynovich, A.; Kwietniewskic, M.; Romanovski, V. Evaluation of the possibility of utilization of sewage sludge from a wastewater treatment plant—Case study. Desalination Water Treat. 2021, 227, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacprzak, M.; Baran, J.; Fijalkowski, K. Emerging sewage sludge treatment technologies for land carbon sequestration: A comprehensive review. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2025, 27, 2866–2886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieślik, B.M.; Namieśnik, J.; Konieczka, P. Review of sewage sludge management: Standards, regulations and analytical methods. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 90, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacprzak, M.; Baran, J.; Neczaj, E.; Fijałkowski, K.; Grobelak, A.; Grosser, A.; Worwag, M.; Rorat, A.; Brattebo, H.; Almåsc, Å.; et al. Sewage sludge disposal strategies for sustainable development. Environ. Res. 2017, 156, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- No. 50/2001 (IV.3.); Government Decree No. 50/2001 (IV.3.) on the Rules for the Agricultural Use and Treatment of Wastewater and Sewage Sludge. Magyar Közlöny (Hungarian Official Gazette): Budapest, Hungary, 2001; pp. 2532–2543.

- Alvarenga, P.; Farto, M.; Mourinha, C.; Palma, P. Beneficial Use of Dewatered and Composted Sewage Sludge as Soil Amendments: Behaviour of Metals in Soils and Their Uptake by Plants. Waste Biomass Valor. 2016, 7, 1189–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, T.M.; Bottlinger, M.; Schulz, E.; Leandro, W.M.; de Aguiar Filho, A.M.; Wang, H.; Ok, Y.S.; Rinklebe, J. Plant and soil responses to hydrothermally converted sewage sludge (sewchar). Chemosphere 2018, 206, 338–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonkiewicz, J.; Popławska, A.; Kołodziej, B.; Ciarkowska, K.; Gambus, F.; Bryk, M.; Babula, J. Application of ash and municipal sewage sludge as macronutrient sources in sustainable plant biomass production. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 264, 110450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wydro, U.; Jabłońska-Trypuć, A.; Hawrylik, E.; Butarewicz, A.; Rodziewicz, J.; Janczukowicz, W.; Wołejko, E. Heavy Metals Behavior in Soil/Plant System after Sewage Sludge Application. Energies 2021, 14, 1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.L.L.; Yang, X.E.; Stoffelia, P.J. Trace elements in agroecosystems and impacts on the environment. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2005, 19, 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grobelak, A.; Placek, A.; Grosser, A.; Singh, B.R.; Almås, Å.R.; Napora, A. Effects of single sewage sludge application on soil phytoremediation. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 155, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csete, S.; Stranczinger, S.; Szalontai, B.; Farkas, A.; Salamon-Albert, É.; Kocsis, M.; Vojtela, T. Tall Wheatgrass Cultivar Szarvasi-1 (Elymus elongatus Subsp. Ponticus cv. Szarvasi-1) as a Potential Energy Crop for Semi-Arid Lands of Eastern Europe. In Sustainable Growth and Applications in Renewable Energy Sources; Nayeripour, M., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2011; pp. 269–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipos, G.; Solti, Á.; Czech, V.; Vashegyi, I.; Tóth, B.; Cseh, E.; Fodor, F. Heavy metal accumulation and tolerance of energy grass (Elymus elongatus subsp. ponticus cv. Szarvasi-1) grown in hydroponic culture. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2013, 68, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcoverde Cerveira Sterner, V.; Jobbágy, K.; Tóth, B.; Rudnóy, S.; Sipos, G.; Fodor, F. Increasing salinity sequentially induces salt tolerance responses in Szarvasi-1 energy grass. Plant Stress 2024, 14, 100572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, D.; Arcoverde Cerveira Sterner, V.; May, Z.; Sipos, G.; Fodor, F. Combined metal treatments cause marked changes in the ionomic patterns in Szarvasi-1 energy grass shoot biomass. Plant Soil. 2025, 513, 2023–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoratos, P.; Moirou, A.; Xenidis, A.; Paspaliaris, I. The use of municipal sewage sludge for the stabilization of soil contaminated by mining activities. J. Hazard. Mater. 2000, 77, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Shan, Y. Effects of Sewage Sludge on Soil Physical, Chemical and Biological Properties. Front. Sustain. Dev. 2025, 5, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonova, K.; Holatko, J.; Hammerschmiedt, T.; Mravcova, L.; Kucerik, J.; Mustafa, A.; Kintl, A.; Naveed, M.; Racek, J.; Grulichova, M.; et al. Microwave pyrolyzed sewage sludge: Influence on soil microbiology, nutrient status, and plant biomass. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2022, 9, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianico, A.; Braguglia, C.M.; Gallipoli, A.; Montecchio, D.; Mininni, G. Land Application of Biosolids in Europe: Possibilities, Con-Straints and Future Perspectives. Water 2021, 13, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucia, C.; Badalucco, L.; Corsino, S.F.; Galati, A.; Iovino, M.; Muscarella, S.M.; Paliaga, S.; Torregrossa, M.; Laudicina, V.A. Management and valorisation of sewage sludge to foster the circular economy in the agricultural sector. Discov. Soil 2025, 2, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobiuc, A.; Stoleru, V.; Gheorghiţă, R.; Burducea, M. The Effect of Municipal Biosolids on the Growth, Physiology and Synthesis of Phenolic Compounds in Ocimum basilicum L. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 25, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowski, K.J.; Kołodziej, B.; Dubis, B.; Sugier, D.; Antonkiewicz, J.; Szatkowski, A. The effect of sewage sludge on the energy balance of cup plant biomass production. A six-year field experiment in Poland. Energy 2023, 276, 127478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paganini, E.A.L.; Silva, R.B.; Ribeiro Roder, L.; Guerrini, I.A.; Capra, G.F.; Grilli, E.; Ganga, A. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Sustainable Impact of Sewage Sludge Application on Soil Organic Matter and Nutrient Content. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubišová, M.; Horník, M.; Hrčková, K.; Gubiš, J.; Jakubcová, A.; Hudcovicová, M.; Ondreičková, K. Sewage Sludge as a Soil Amendment for Growing Biomass Plant Arundo donax L. Agronomy 2020, 10, 678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szostek, M.; Kosowski, P.; Szpunar-Krok, E.; Jańczak-Pieniążek, M.; Matłok, N.; Skrobacz, K.; Pieniążek, R.; Balawejder, M. The Usefulness of Ozone-Stabilized Municipal Sewage Sludge for Fertilization of Maize (Zea mays L.). Agriculture 2022, 12, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, E.T.; Caetano, L.E.S.; Candido, J.M.B.; Cechin, I.; da Silva, G.H.R. Enhancing Plant Growth and Photosynthesis with Biofertilizers from Sewage Treatment. Agronomy 2025, 15, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Gao, Y.; Sun, S.; Lu, X.; Li, Q.; Li, L.; Wang, K.; Liu, J. Effects of Salt Stress on the Antioxidant Activity and Malondialdehyde, Solution Protein, Proline, and Chlorophyll Contents of Three Malus Species. Life 2022, 12, 1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maathuis, F.J.M. Sodium in plants: Perception, signalling, and regulation of sodium fluxes. J. Exp. Bot. 2014, 65, 849–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achkir, A.; Aouragh, A.; El Mahi, M.; Lotfi, E.M.; Labjar, N.; EL Bouch, M.; Ouahidi, M.L.; Badza, T.; Farhane, H.; EL Moussaoui, T. Implication of sewage sludge increased application rates on soil fertility and heavy metals contamination risk. Emerg. Contam. 2023, 9, 100200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Rosario, L.Y.; Harms, K.E.; Elderd, B.D.; Hart, P.B.; Dassanayake, M. No escape: The influence of substrate sodium on plant growth and tissue sodium responses. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 11, 14231–14249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchmann, H.; Börjesson, G.; Kätterer, T.; Cohen, Y. From agricultural use of sewage sludge to nutrient extraction: A soil science outlook. Ambio 2017, 46, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, S.; Singh, P.K.; Mankotia, S.; Swain, J.; Satbhai, S.B. Iron homeostasis in plants and its crosstalk with copper, zinc, and manganese. Plant Stress 2021, 1, 100008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, K.; Ahmad, Z.; Kobayashi, T.; Seki, M.; Nishizawa, N.K. Roles of subcellular metal homeostasis in crop improvement. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 2083–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolberg, F.; Tóth, B.; Rana, D.; Arcoverde Cerveira Sterner, V.; Gerényi, A.; Solti, Á.; Szalóki, I.; Sipos, G.; Fodor, F. Iron Status Affects the Zinc Accumulation in the Biomass Plant Szarvasi-1. Plants 2022, 11, 3227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.; Li, C.; Yan, J.; Ma, Y.; Zhou, X.; Yu, W.; Kan, H.; Meng, Q.; Xie, R.; Dong, P. A review on adsorption characteristics and influencing mechanism of heavy metals in farmland soil. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 3505–3519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medyńska-Juraszek, A.; Rivier, P.-A.; Rasse, D.; Joner, E.J. Biochar Affects Heavy Metal Uptake in Plants through Interactions in the Rhizosphere. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 5105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieczko, A.K.; van de Vlasakker, P.C.H.; Tonderski, K.; Metson, G.S. Seasonal nitrogen and phosphorus leaching in urban agriculture: Dominance of non-growing season losses in a Southern Swedish case study. Urban. For. Urban Green. 2022, 79, 127823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draper, H.H.; Hadley, M. Malondialdehyde determination as index of lipid peroxidation. Methods Enzymol. 1990, 186, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhindsa, R.H.; Plumb-Dhindsa, P.; Thorpe, T.A. Leaf senescence: Correlated with increased levels of membrane permeability and lipid peroxidation, and decreased levels of superoxide dismutase and catalase. J. Exp. Bot. 1981, 32, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, R.L.; Packer, L. Photoperoxidation in isolated chloroplasts: I. Kinetics and stoichiometry of fatty acid peroxidation. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1968, 125, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barócsi, A.; Lenk, S.; Kocsányi, L.; Buschmann, C. Excitation kinetics during induction of chlorophyll a fluorescence. Photosynthetica 2009, 47, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dry matter content | [kg d.m. kg−1] | 0.255 ± 0.014 | ||

| pH | 8.58 ± 0.22 | |||

| Element | Concentration | L1 | L2 | |

| Ca | [g kg−1 d.m.] | 55.55 ± 1.34 | ||

| Mg | [g kg−1 d.m.] | 7.26 ± 0.01 | ||

| K | [g kg−1 d.m.] | 2.43 ± 0.85 | ||

| N | [g kg−1 d.m.] | 45.25 ± 2.85 | ||

| P | [g kg−1 d.m.] | 30.79 ± 8.55 | ||

| S | [g kg−1 d.m.] | 15.15 ± 1.20 | ||

| Na | [g kg−1 d.m.] | 5.26 ± 0.00 | ||

| B | [mg kg−1 d.m.] | 29.95 ± 5.43 | ||

| Mn | [mg kg−1 d.m.] | 209.25 ± 34.83 | ||

| Zn | [mg kg−1 d.m.] | 669.00 ± 164.97 | 2500 | 30 |

| Cu | [mg kg−1 d.m.] | 371.75 ± 48.22 | 1000 | 10 |

| Fe | [mg kg−1 d.m.] | 3520.00 ± 890.95 | ||

| Ni | [mg kg−1 d.m.] | 30.60 ± 7.52 | 200 | 2.0 |

| Al | [mg kg−1 d.m.] | 4143.25 ± 2313.96 | ||

| Mo | [mg kg−1 d.m.] | 5.18 ± 1.07 | 20 | 0.2 |

| As | [mg kg−1 d.m.] | 5.52 ± 1.08 | 75 | 0.5 |

| Cd | [mg kg−1 d.m.] | 2.09 ± 0.69 | 10 | 0.15 |

| Co | [mg kg−1 d.m.] | 5.17 ± 3.23 | 50 | 0.5 |

| Cr | [mg kg−1 d.m.] | 33.15 ± 10.48 | 1000 | 10 |

| Hg | [mg kg−1 d.m.] | 0.71 ± 0.06 | 10 | 0.1 |

| Pb | [mg kg−1 d.m.] | 44.60 ± 2.31 | 750 | 10 |

| Organic contaminant | ||||

| TPH 1 | [mg kg−1 d.m.] | 3890.00 ± 169.71 | 4000 | 40 |

| PAH 2 | [mg kg−1 d.m.] | 1.82 ± 0.38 | 10,000 | 0.1 |

| PCB 3 | [mg kg−1 d.m.] | <0.01 | 1 | 0.05 |

| Element | Treatments | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S0 | S1 | S2 | S3 | |

| Ca | 6202 ± 1223 | 7646 ± 1363 | 8010 ± 1429 | 8121 ± 2210 |

| Mg | 1453 ± 358 | 1907 ± 519 | 2055 ± 544 | 2020 ± 453 |

| K | 24,967 ± 5643 | 31,886 ± 7640 | 29,420 ± 9933 | 32,776 ± 9506 |

| N | 19,437 ± 5532 | 29,405 ± 8970 | 29,570 ± 9972 | 28,824 ± 8885 |

| P | 2334 ± 316 | 2154 ± 577 | 2140 ± 497 | 1982 ± 386 |

| S | 2338 ± 705 | 3195 ± 656 | 4488 ± 2226 | 2975 ± 1051 |

| Na | 2874 ± 601 | 4103 ± 2521 | 6441 ± 2302 | 5345 ± 2702 |

| B | 25.09 ± 18.38 | 33.97 ± 33.43 | 28.52 ± 26.07 | 26.92 ± 20.05 |

| Mn | 23.48 ± 12.20 | 22.03 ± 5.77 | 24.63 ± 11.10 | 23.89 ± 10.57 |

| Zn | 18.96 ± 5.49 | 21.25 ± 6.98 | 24.79 ± 10.95 | 27.09 ± 12.70 |

| Cu | 8.29 ± 4.47 | 10.00 ± 6.36 | 10.69 ± 6.58 | 11.05 ± 7.26 |

| Fe | 96.32 ± 54.42 | 122.91 ± 59.13 | 139.52 ± 79.01 | 131.20 ± 65.91 |

| Ni | 2.12 ± 1.97 | 0.96 ± 0.55 | 1.19 ± 0.66 | 1.74 ± 1.88 |

| Al | 68.90 ± 37.97 | 74.53 ± 44.74 | 68.84 ± 41.10 | 78.77 ± 50.11 |

| As | 1.22 ± 0.32 | 1.28 ± 0.63 | 1.27 ± 0.61 | 1.22 ± 0.48 |

| Cd | 0.22 ± 0.05 | 0.21 ± 0.01 | 0.21 ± 0.02 | 0.20 ± 0.00 |

| Pb | 2.25 ± 0.75 | 1.87 ± 0.27 | 1.60 ± 0.40 | 2.59 ± 1.00 |

| Element | Treatments | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S0 | S1 | S2 | S3 | |

| Ca | 7508 ± 3165 | 7851 ± 3056 | 8354 ± 2551 | 9224 ± 3962 |

| Mg | 1468 ± 640 | 1363 ± 540 | 1770 ± 924 | 1917 ± 981 |

| K | 22,285 ± 7134 | 24,001 ± 8272 | 21,917 ± 8707 | 23,853 ± 8407 |

| N | 17,850 ± 12,857 | 25,943 ± 13,023 | 28,170 ± 14,867 | 31,390 ± 16,206 |

| P | 2514 ± 497 | 2131 ± 189 | 2044 ± 445 | 1863 ± 370 |

| S | 3115 ± 771 | 3225 ± 1181 | 3505 ± 1747 | 4755 ± 431 |

| Na | 1167 ± 715 | 857 ± 503 | 1940 ± 201 | 2687 ± 1880 |

| B | 16.32 ± 10.61 | 20.58 ± 17.97 | 15.26 ± 7.13 | 15.16 ± 11.38 |

| Mn | 20.48 ± 13.74 | 10.76 ± 3.76 | 21.24 ± 16.13 | 19.98 ± 16.10 |

| Zn | 25.12 ± 12.25 | 26.89 ± 11.86 | 34.54 ± 29.73 | 30.00 ± 11.87 |

| Cu | 5.92 ± 2.28 | 7.76 ± 2.64 | 8.77 ± 4.24 | 8.01 ± 2.45 |

| Fe | 59.92 ± 38.56 | 67.02 ± 40.34 | 60.78 ± 48.59 | 76.00 ± 58.02 |

| Ni | 1.33 ± 0.58 | 0.91 ± 0.91 | 1.06 ± 0.38 | 0.63 ± 0.23 |

| Al | 129.30 ± 123.26 | 113.01 ± 137.02 | 109.59 ± 120.50 | 123.27 ± 162.02 |

| As | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.74 ± 1.48 | 1.54 ± 1.08 | 1.60 ± 1.20 |

| Cd | 0.22 ± 0.04 | 0.26 ± 0.09 | 0.20 ± 0.00 | 0.22 ± 0.03 |

| Pb | 0.46 ± 0.51 | 0.45 ± 0.51 | 0.56 ± 0.68 | 0.48 ± 0.55 |

| Element | Treatments | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 2017–2018 | |||||

| S1 | S2 | S3 | S1 | S2 | S3 | |

| Ca | 0.065 | 0.056 | 0.046 | 0.060 | 0.053 | 0.044 |

| Mg | 0.127 | 0.115 | 0.093 | 0.123 | 0.111 | 0.086 |

| K | 7.247 | 5.367 | 4.939 | 6.250 | 5.178 | 4.420 |

| N | 0.285 | 0.265 | 0.196 | 0.298 | 0.269 | 0.195 |

| P | 0.049 | 0.042 | 0.031 | 0.035 | 0.033 | 0.023 |

| S | 0.102 | 0.193 | 0.061 | 0.089 | 0.142 | 0.053 |

| Na | 0.349 | 0.464 | 0.366 | 0.424 | 0.519 | 0.371 |

| B | 0.177 | 0.154 | 0.122 | 0.336 | 0.253 | 0.091 |

| Mn | 0.061 | 0.054 | 0.046 | 0.054 | 0.054 | 0.041 |

| Zn | 0.012 | 0.011 | 0.009 | 0.014 | 0.015 | 0.012 |

| Cu | 0.010 | 0.009 | 0.008 | 0.014 | 0.012 | 0.010 |

| Fe | 0.025 | 0.028 | 0.019 | 0.017 | 0.018 | 0.013 |

| Ni | 0.029 | 0.028 | 0.059 | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.028 |

| Al | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.069 | 0.100 | 0.088 | 0.061 |

| As | 0.101 | 0.088 | 0.069 | 0.100 | 0.088 | 0.061 |

| Cd | 0.088 | 0.076 | 0.060 | 0.051 | 0.044 | 0.034 |

| Pb | 0.024 | 0.015 | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.010 | 0.012 |

| Element | Treatments | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 2017–2018 | 2017–2019 | |||||||

| S1 | S2 | S3 | S1 | S2 | S3 | S1 | S2 | S3 | |

| Ca | 0.091 | 0.054 | 0.041 | 0.100 | 0.065 | 0.048 | 0.118 | 0.080 | 0.058 |

| Mg | 0.132 | 0.086 | 0.062 | 0.136 | 0.111 | 0.076 | 0.162 | 0.127 | 0.094 |

| K | 8.210 | 4.521 | 3.614 | 5.543 | 3.240 | 2.247 | 6.583 | 3.751 | 2.759 |

| N | 0.201 | 0.148 | 0.134 | 0.268 | 0.213 | 0.164 | 0.309 | 0.251 | 0.199 |

| P | 0.036 | 0.021 | 0.014 | 0.034 | 0.022 | 0.013 | 0.046 | 0.029 | 0.017 |

| S | 0.147 | 0.093 | 0.073 | 0.297 | 0.205 | 0.165 | 0.408 | 0.287 | 0.253 |

| Na | 0.059 | 0.127 | 0.074 | 0.094 | 0.157 | 0.137 | 0.167 | 0.221 | 0.216 |

| B | 0.244 | 0.152 | 0.100 | 0.316 | 0.183 | 0.103 | 0.735 | 0.335 | 0.256 |

| Mn | 0.038 | 0.023 | 0.015 | 0.029 | 0.038 | 0.023 | 0.039 | 0.045 | 0.028 |

| Zn | 0.014 | 0.008 | 0.007 | 0.024 | 0.021 | 0.011 | 0.031 | 0.024 | 0.015 |

| Cu | 0.009 | 0.006 | 0.004 | 0.012 | 0.009 | 0.005 | 0.014 | 0.010 | 0.007 |

| Fe | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.001 |

| Ni | 0.007 | 0.010 | 0.004 | 0.010 | 0.011 | 0.005 | 0.026 | 0.018 | 0.006 |

| Al | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.016 | 0.012 | 0.007 | 0.044 | 0.028 | 0.024 |

| As | 0.079 | 0.045 | 0.032 | 0.192 | 0.107 | 0.071 | 0.234 | 0.135 | 0.093 |

| Cd | 0.064 | 0.036 | 0.028 | 0.065 | 0.031 | 0.022 | 0.085 | 0.045 | 0.033 |

| Pb | 0.013 | 0.009 | 0.005 | 0.009 | 0.006 | 0.003 | 0.010 | 0.007 | 0.004 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Fodor, F.; Nyitrai, P.; Sárvári, É.; Gyuricza, C.; Sipos, G. Evaluating the Sustainability of High-Dose Sewage Sludge Application in Fertilizing Szarvasi-1 Energy Grass Plantations. Plants 2026, 15, 392. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15030392

Fodor F, Nyitrai P, Sárvári É, Gyuricza C, Sipos G. Evaluating the Sustainability of High-Dose Sewage Sludge Application in Fertilizing Szarvasi-1 Energy Grass Plantations. Plants. 2026; 15(3):392. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15030392

Chicago/Turabian StyleFodor, Ferenc, Péter Nyitrai, Éva Sárvári, Csaba Gyuricza, and Gyula Sipos. 2026. "Evaluating the Sustainability of High-Dose Sewage Sludge Application in Fertilizing Szarvasi-1 Energy Grass Plantations" Plants 15, no. 3: 392. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15030392

APA StyleFodor, F., Nyitrai, P., Sárvári, É., Gyuricza, C., & Sipos, G. (2026). Evaluating the Sustainability of High-Dose Sewage Sludge Application in Fertilizing Szarvasi-1 Energy Grass Plantations. Plants, 15(3), 392. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15030392