Floristic Composition and Diversity Along a Successional Gradient in Andean Montane Forests, Southwestern Colombia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

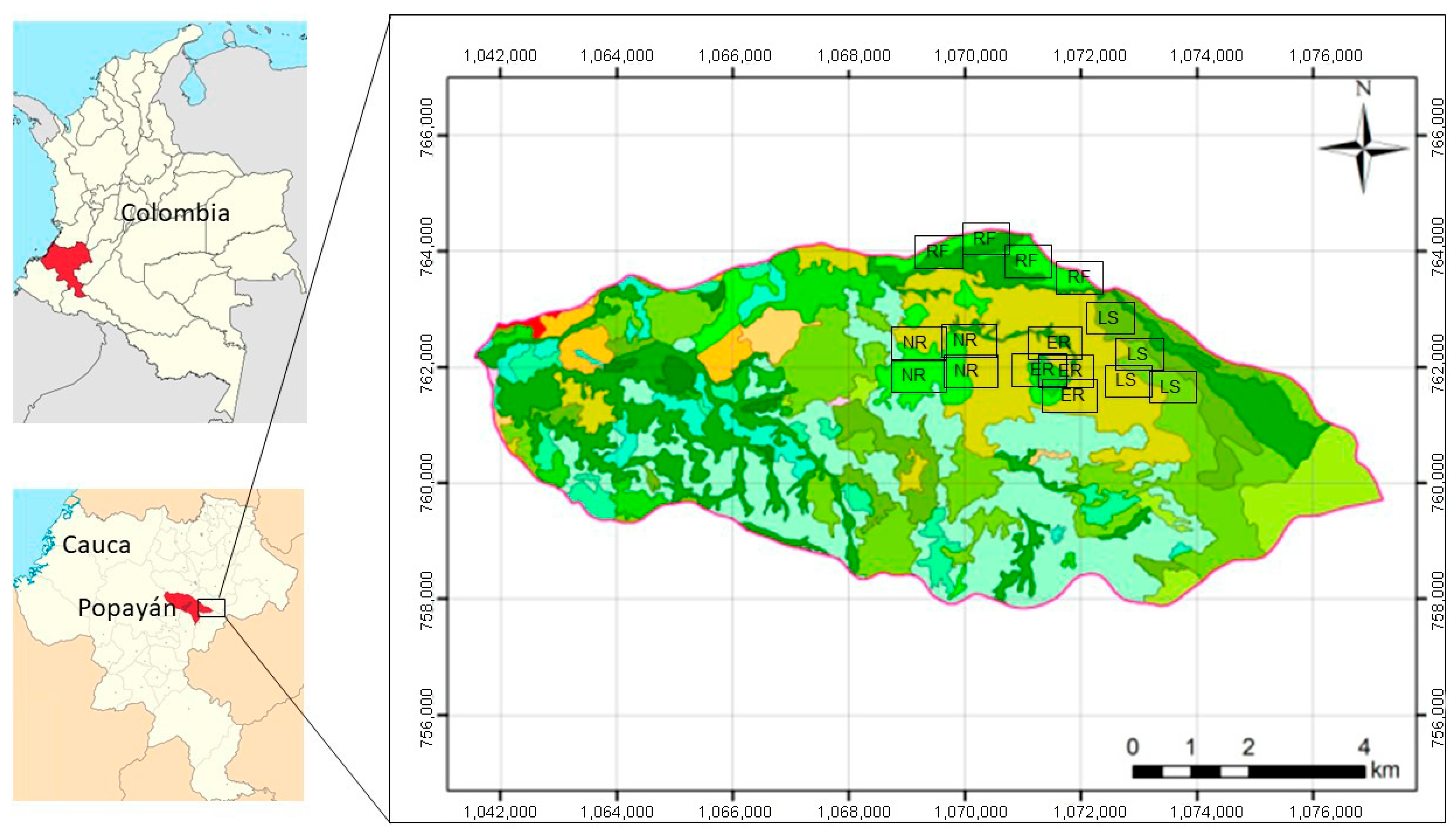

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Vegetation Sampling

2.3. Taxonomic Identification

2.4. Structural and Diversity Analyses

2.5. Data Processing, Software, and Visualization

3. Results

3.1. Species Composition

3.2. Forest Structure of Land Uses

3.3. Diameter Distribution

3.4. Altimetric Distribution

3.5. Ecological Indices

3.6. Species Richness, Rarefaction, and Sampling Completeness

4. Discussion

4.1. Floristic Composition and Forest Structure

4.2. Diversity, Ecological Succession and Implications for Restoration

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Hernández-blanco, M.; Costanza, R.; Chen, H.; Jarvis, D.; Montoya, J.; Sangha, K.; Stoeckl, N.; Turner, K.; Van Hoff, V. Ecosystem Health, Ecosystem Services, and the Well-Being of Humans and the Rest of Nature. Glob. Change Biol. 2022, 28, 5027–5040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevance, A.S.; Bridgewater, P.; Louafi, S.; King, N.; Beard, T.D.; Van Jaarsveld, A.S.; Ofir, Z.; Kohsaka, R.; Jenderedijan, K.; Rosales Benites, M.; et al. The 2019 Review of IPBES and Future Priorities: Reaching beyond Assessment to Enhance Policy Impact. Ecosyst. People 2020, 16, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kier, G.; Mutke, J.; Dinerstein, E.; Ricketts, T.H. Global Patterns of Plant Diversity and Floristic Knowledge. J. Biogeogr. 2005, 32, 1107–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, S.P. Objetivos y Estrategias de La Cooperación Española Para La Conservación de La Agrobiodiversidad En La Región Andina Central. 2023. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10234/203381 (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Comer, P.J.; Valdez, J.; Pereira, H.M.; Acosta-muñoz, C.; Campos, F.; Javier, F.; Garc, B.; Claros, X.; Castro, L.; Dallmeier, F.; et al. Conserving Ecosystem Diversity in the Tropical Andes. Remote. Sens. 2022, 14, 2847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benavides, J.C.; Arenas-Bautista, M.C. The Andes: The Physical Setting. In Andean Herpetofauna; Sustainable Development Goals Series; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2026; pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, M.; Armenteras, D. Colombian Andean Cloud Forests Conservation Status, A Multiscalar Analysis. Boletín Científico. Cent. Museos. Mus. Hist. Nat. 2013, 17, 64–72. [Google Scholar]

- Marcelo, D.; Bank, W.; Rodr, N. Biodiversidad Y Actividad Humana: Relaciones En Ecosistemas De Bosque; Instituto de Investigación de Recursos Biológicos Alexander von Humboldt: Bogotá, Colombia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Por, P.; Alonso, J.; Delgado, M.; De Biología, P. Incidencia Antrópica En La Composición Florística, Estructural y Comportamiento de Rasgos Funcionales En La Comunidad de Manglar En Cartagena de Indias, Colombia. 2022. Available online: http://repositoriodspace.unipamplona.edu.co/jspui/handle/20.500.12744/9624 (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Cuesta, F.; Muriel, P.; Llambí, L.D.; Halloy, S.; Aguirre, N.; Beck, S.; Carilla, J.; Meneses, R.I.; Cuello, S.; Grau, A.; et al. Latitudinal and Altitudinal Patterns of Plant Community Diversity on Mountain Summits across the Tropical Andes. Ecography 2017, 40, 1381–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadán, O.; Donoso, D.A.; Cedillo, H.; Bermúdez, F.; Cabrera, O. Floristic Groups, and Changes in Diversity and Structure of Trees, in Tropical Montane Forests in the Southern Andes of Ecuador. Diversity 2021, 13, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.R.; Barbosa, M.A.G.A.; Bolleli, T.; Anjinho, P.S.; Roque, R.; Mauad, F.F. Assessment of Water Ecosystem Integrity (WEI) in a Transitional Brazilian Cerrado–Atlantic Forest Interface. Water 2023, 15, 775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfonso, V.; Valencia, M.; Casas, A.F.; Jesús, D.; Pinto, M. Modeling Soil Organic Carbon Dynamics Across Land Uses in Tropical Andean Ecosystems. Land 2025, 14, 2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondragón Valencia, V.A.; Figueroa Casas, A.; Macias Pinto, D.J.; Rosas-Luis, R. Soil Organic Carbon Storage in Different Land Uses in Tropical Andean Ecosystems and the Socio-Ecological Environment. Earth 2025, 6, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, J. Inventarios Forestales Nacionales de América Latina y El Caribe: Hacia La Armonización de La Información Forestal; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gentry, A.H. Diversity and Floristic Composition of Neotropical Dry Forests. Seas. Dry Trop. For. 1995, 1, 146–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-Cifuentes, H. Patrones De Riqueza Específica De Las Familias Melastomataceae Y Rubiaceae En La Cordillera Oriental, Colombia, Norte De Los Andes Y Consideraciones Para La Conservación. Colomb. For. 2012, 15, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Vargas, L.E.; Becoche Mosquera, J.M.; Macías Pinto, D.J.; Ruiz Montoya, K.; Velasco Reyes, A.; Pineda, S. Estructura Y Composición Florística De La Reserva Forestal—Institución Educativa Cajete, Popayán (Cauca). Luna Azul 2015, 41, 131–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangel-Ch, J.O.; Velázquez, A. Metodos de Estudio de La Vegetación. Colomb. Divers. Biot. II 1997, 378, 59–87. [Google Scholar]

- Magurran, A.E. Diversity Indices and Species Abundance Models. In Ecological Diversity and Its Measurement; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1988; pp. 7–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotelli, N.J.; Colwell, R.K. Quantifying Biodiversity: Procedures and Pitfalls in the Measurement and Comparison of Species Richness. Ecol. Lett. 2001, 4, 379–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baselga, A. Partitioning the Turnover and Nestedness Components of Beta Diversity. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2010, 19, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varsos, C.; Patkos, T.; Oulas, A.; Pavloudi, C.; Gougousis, A.; Ijaz, U.Z.; Filiopoulou, I.; Pattakos, N.; Berghe, E.V.; Fernández-Guerra, A.; et al. Optimized R Functions for Analysis of Ecological Community Data Using the R Virtual Laboratory (RvLab). Biodivers. Data J. 2016, 4, e8357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wickham, H. Ggplot2. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Stat. 2011, 3, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín, J.; Baptiste, T.M.G.; Rodero, C.; Williams, S.E.; Niederer, S.A.; García-Fernández, I. SciBlend: Advanced Data Visualization Workflows within Blender. Comput. Graph. 2025, 130, 104264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, O. PAST: Paleontological Statistics Software Package for Education and Data Analysis. Palaeontol. Electron. 2001, 4, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Baselga, A.; Orme, C.D.L. Betapart: An R Package for the Study of Beta Diversity. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2012, 3, 808–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guariguata, M.R.; Ostertag, R. Sucesión Secundaria. Bosques Neotropicales. Editorial Tecnológica, Cartago, Costa Rica. 2014. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/235942869 (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- de Oliveira Loconte, C. The Volumetric Sustainability of Timber-Based Tropical Forest Management. In Forest Science. Environmental Footprints and Eco-Design of Products and Processes; Springer: Singapore, 2023; pp. 51–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chazdon, R.L. Tropical Forest Recovery: Legacies of Human Impact and Natural Disturbances. Perspect. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2003, 6, 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Garza, C.; Howe, H.F. Restoring Tropical Diversity: Beating the Time Tax on Species Loss. J. Appl. Ecol. 2003, 40, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuo, T.; Martínez-Ramos, M.; Bongers, F.; van der Sande, M.T.; Poorter, L. Forest Structure Drives Changes in Light Heterogeneity during Tropical Secondary Forest Succession. J. Ecol. 2021, 109, 2871–2884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakovac, C.C.; Junqueira, A.B.; Crouzeilles, R.; Peña-Claros, M.; Mesquita, R.C.G.; Bongers, F. The Role of Land-Use History in Driving Successional Pathways and Its Implications for the Restoration of Tropical Forests. Biol. Rev. 2021, 96, 1114–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavieres, L.A.; Llambí, L.D.; Anthelme, F.; Hofstede, R.; Arroyo, M.T.K. High-Andean Vegetation Under Environmental Change: A Continental Synthesis. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2025, 50, 219–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomeque Pesantez, F.X. Natural Succession and Tree Plantation as Alternatives for Restoring Abandoned Lands in the Andes of Southern Ecuador: Aspects of Facilitation and Competition. Ph.D. Thesis, Technical University of Munich, Munich, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Howorth, R.T.; Pendry, C.A. Post-Cultivation Secondary Succession in a Venezuelan Lower Montane Rain Forest. Biodivers. Conserv. 2006, 15, 693–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poorter, L.; Rozendaal, D.M.A.; Bongers, F.; de Jarcilene, S.A.; Àlvarez, F.S.; Luìs Andrade, J.; Arreola Villa, L.F.; Becknell, J.M.; Bhaskar, R.; Boukili, V.; et al. Functional Recovery of Secondary Tropical Forests. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2003405118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenfield, M.F.; Jakovac, C.C.; Vieira, D.L.M.; Poorter, L.; Brancalion, P.H.S.; Vieira, I.C.G.; de Almeida, D.R.A.; Massoca, P.; Schietti, J.; Albernaz, A.L.M.; et al. Ecological Integrity of Tropical Secondary Forests: Concepts and Indicators. Biol. Rev. 2023, 98, 662–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.C. Insects and Forest Succession. In Forest Entomology and Pathology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 1, pp. 205–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finegan, B. Pattern and Process in Neotropical Secondary Rain Forests: The First 100 Years of Succession. Trends Ecol. Evol. 1996, 11, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dent, D.H.; Joseph Wright, S. The Future of Tropical Species in Secondary Forests: A Quantitative Review. Biol. Conserv. 2009, 142, 2833–2843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanaphre-Villanueva, L.; Dupuy, J.M.; Andrade, J.L.; Reyes-García, C.; Paz, H.; Jackson, P.C. Functional Diversity of Small and Large Trees along Secondary Succession in a Tropical Dry Forest. Forests 2016, 7, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larocque, G.R.; Shugart, H.H.; Xi, W.; Holm, J.A. Forest Succession Models. In Ecological Forest Management Handbook; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024; pp. 166–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holl, K.D. Restoration of Tropical Forests. In Restoration Ecology: The New Frontier; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouzeilles, R.; Ferreira, M.S.; Chazdon, R.L.; Lindenmayer, D.B.; Sansevero, J.B.B.; Monteiro, L.; Iribarrem, A.; Latawiec, A.E.; Strassburg, B.B.N. Ecological Restoration Success Is Higher for Natural Regeneration than for Active Restoration in Tropical Forests. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1701345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, J.; Panichini, M.; Neira, P.; Henríquez-Castillo, C.; Gallardo Jara, R.E.; Rodriguez, R.; Mutis, A.; Ramos, C.; Espejo, W.; Puc-Kauil, R.; et al. How Natural Regeneration After Severe Disturbance Affects Ecosystem Services Provision of Andean Forest Soils at Contrasting Timescales. Forests 2025, 16, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariscal, A.; Tigabu, M.; Savadogo, P.; Odén, P.C. Regeneration Status and Role of Traditional Ecological Knowledge for Cloud Forest Ecosystem Restoration in Ecuador. Forests 2022, 13, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, A.; Gotelli, N.J.; Hsieh, T.C.; Sander, E.L.; Ma, K.H.; Colwell, R.K.; Ellison, A.M. Rarefaction and Extrapolation with Hill Numbers: A Framework for Sampling and Estimation in Species Diversity Studies. Ecol. Monogr. 2014, 84, 45–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chazdon, R.L. Second Growth: The Promise of Tropical Forest Regeneration in an Age of Deforestation; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Jaen, M.C.; Aide, T.M. Restoration Success: How Is It Being Measured? Restor. Ecol. 2005, 13, 569–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legendre, P. Interpreting the Replacement and Richness Difference Components of Beta Diversity. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2014, 23, 1324–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, T.P.; Chase, J.M.; Huddleston, R.T. Community Succession and Assembly. Ecol. Restor. 2001, 19, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Family | Species | RF | ER | NR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actinidiaceae | Saurauia scabra (Kunth) D.Dietr. | X | ||

| Alstroemeriaceae | Bomarea patinii Baker | X | X | |

| Alzateaceae | Alzatea verticillata Ruiz & Pav | X | ||

| Araliaceae | Oreopanax incisus (Willd. ex Schult.) Decne. & Planch. | X | X | |

| Asteraceae | Ageratina theifolia (Benth.) R.M.King & H.Rob. | X | ||

| Baccharis sp. | X | |||

| Cirsium vulgare (Savi) Ten | X | |||

| Gynoxys sp. | X | |||

| Smallanthus pyramidalis (Triana) H.Rob | X | X | ||

| Chromolaena ivifolia (L.) R.King & H.Rob. | X | |||

| Chloranthaceae | Hedyosmum cumbalense H.Karst. | X | X | |

| Clusiaceae | Clusia alata Planch. & Triana | X | ||

| Clusia multiflora Kunth | X | |||

| Cunoniaceae | Weinmannia tomentosa L.f. | X | ||

| Cyatheaceae | Cyathea sp. | X | ||

| Cyperaceae | Rhynchospora nervosa (Vahl) Boeckeler | X | ||

| Ericaceae | Bejaria resinosa Mutis ex L.fil. | X | ||

| Vaccinium meridionale Sw. | X | X | ||

| Escalloniaceae | Escallonia myrtilloides L.fil. | X | ||

| Escallonia paniculata (Ruiz & Pav.) Roem. & Schult. | X | |||

| Euphorbiaceae | Aparisthmium cordatum (A.Juss.) Baill | X | ||

| Fabaceae | Inga densiflora Benth. | X | ||

| Fagaceae | Quercus humboldtii Bonpl. | X | ||

| Gesneriaceae | Columnea cf. sanguinea (Pers.) Hanst. | X | ||

| Kohleria warszewiczii (Regel) Hanst. | X | |||

| Juglandaceae | Juglans neotropica Diels | X | ||

| Lauraceae | Aniba perutilis Hemsl. | X | ||

| Nectandra mollis (Kunth) Nees | X | |||

| Ocotea oblonga (Meisn.) Mez | X | |||

| Melastomataceae | Andesanthus lepidotus (Humb. & Bonpl.) P.J.F.Guim. & Michelang. | X | ||

| Axinaea macrophylla Triana | X | |||

| Chaeotogastra grossa (L.fil.) P.J.F.Guim. & Michelang. | X | X | ||

| Chaetogastra mollis (Bonpl.) DC. | X | X | ||

| Meriania nobilis Triana | X | |||

| Meriania speciosa (Bonpl.) Naudin | X | |||

| Miconia notabilis Triana | X | X | ||

| Miconia theaezans (Bonpl.) Cogn. | X | X | ||

| Monochaetum sp. | X | |||

| Meliaceae | Cedrela odorata L.f. | X | ||

| Myricaceae | Morella pubescens (Humb. & Bonpl. ex Willd.) Wilbur | X | ||

| Myrsinaceae | Myrsine coriacea (Sw.) R.Br. ex Roem. & Schult. | X | X | |

| Myrtaceae | Myrcia popayanensis Hieron | X | X | |

| Myrcianthes fragans (Sw.) McVaugh | X | |||

| Myrcianthes rhopaloides (Kunth) Mc Vaugh | X | X | ||

| Onagraceae | Fuchsia caucana P.E.Berry | X | ||

| Pentaphylacaceae | Freziera reticulata Bonpl. | X | ||

| Phyllanthaceae | Hieronyma macrocarpa Müll. Arg. | X | ||

| Phyllanthus salviifolius Kunth | X | |||

| Pinaceae | Pinus radiata D.Don | X | ||

| Piperaceae | Piper aduncum L. | X | ||

| Piper crassinervium Kunth. | X | X | ||

| Poaceae | Cenchrus purpureus (Schumach.) Morrone | X | ||

| Chusquea sp. | X | |||

| Cortaderia nitida (Kunth) Pilg. | X | |||

| Holcus lanatus L. | X | |||

| Lolium multiflorum Lam. | X | |||

| Polygalaceae | Monnina salicifolia Ruiz & Pav. | X | ||

| Primulaceae | Stylogyne sp. | X | ||

| Rosaceae | Rubus bogotensis Kunth | X | ||

| Rubiaceae | Cinchona pubescens Vahl | X | X | |

| Coccocypselum lanceolatum (Ruiz & Pav.) Pers. | X | |||

| Elaeagia pastoensis L.E. Mora | X | |||

| Galium hypocarpium (L.) Endl. ex Griseb. | X | |||

| Ladenbergia oblongifolia (Humb. ex Mutis) L.Andersson | X | |||

| Palicourea thyrsifolia (Ruiz & Pav.) DC. | X | |||

| Palicourea angustifolia Kunth | X | X | ||

| Sapotaceae | Pouteria caimito (Ruiz & Pav.) Radlk. | X | ||

| Siparunaceae | Siparuna echinata (Kunth) A.DC | X | ||

| Solanaceae | Solanum cf. venosum Humb. & Bonpl. ex Dunal | X | ||

| Solanum sp. | X | |||

| Urticaceae | Cecropia peltata L. | X | ||

| Viburnaceae | Viburnum pichinchense Benth. | X | ||

| Viburnum triphylum Benth | X | |||

| Winteraceae | Drimys granadensis L.f. | X |

| Plant Cover | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | RF | ER | NR |

| Basal area/ha (m2) | 15.75 ± 0.03 | 16.33 ± 0.02 | 6.08 ± 0.04 |

| No. trees/ha (DAP > 0.1 m) | 1138 ± 0.04 | 1085 ± 0.05 | 873 ± 0.08 |

| Plant Cover | Diameter Classes | DBH Range (m) | Individuals Proportion (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| RF | I | 0.1–0.199 | 42 |

| II | 0.2–0.299 | 33 | |

| III | 0.3–0.399 | 15 | |

| IV | 0.4–0.499 | 10 | |

| ER | I | 0.1–0.199 | 48 |

| II | 0.2–0.299 | 30 | |

| III | 0.3–0.399 | 15 | |

| IV | 0.4–0.499 | 7 | |

| NR | I | 0.1–0.199 | 65 |

| II | 0.2–0.299 | 25 | |

| III | 0.3–0.399 | 7 | |

| IV | 0.4–0.499 | 3 |

| Plant Cover | Altimetric Classes | Height Range (m) | Individuals Proportion (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| RF | I | 1–4.99 | 34 |

| II | 5–9.99 | 40 | |

| III | 10–14.99 | 18 | |

| IV | 15–19.99 | 8 | |

| ER | I | 1–4.99 | 42 |

| II | 5–9.99 | 37 | |

| III | 10–14.99 | 15 | |

| IV | 15–19.99 | 6 | |

| NR | I | 1–4.99 | 55 |

| II | 5–9.99 | 33 | |

| III | 10–14.99 | 9 | |

| IV | 15–19.99 | 3 |

| Plant Cover | Shannon | Simpson |

|---|---|---|

| RF | 2.448895 | 0.8625982 |

| ER | 2.033108 | 0.7933454 |

| NR | 2.890306 | 0.9176203 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mondragón Valencia, V.A.; Chilito, L.G.; Cabezas-Majín, C.E.; Macías Pinto, D.J. Floristic Composition and Diversity Along a Successional Gradient in Andean Montane Forests, Southwestern Colombia. Plants 2026, 15, 389. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15030389

Mondragón Valencia VA, Chilito LG, Cabezas-Majín CE, Macías Pinto DJ. Floristic Composition and Diversity Along a Successional Gradient in Andean Montane Forests, Southwestern Colombia. Plants. 2026; 15(3):389. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15030389

Chicago/Turabian StyleMondragón Valencia, Víctor Alfonso, Luis Gerardo Chilito, Carlos Edward Cabezas-Majín, and Diego Jesús Macías Pinto. 2026. "Floristic Composition and Diversity Along a Successional Gradient in Andean Montane Forests, Southwestern Colombia" Plants 15, no. 3: 389. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15030389

APA StyleMondragón Valencia, V. A., Chilito, L. G., Cabezas-Majín, C. E., & Macías Pinto, D. J. (2026). Floristic Composition and Diversity Along a Successional Gradient in Andean Montane Forests, Southwestern Colombia. Plants, 15(3), 389. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15030389