Sugarcane Breeding in the Genomic Era: Integrative Strategies and Emerging Technologies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Overview of Global Sugarcane Breeding Program

3. Sugarcane Genome

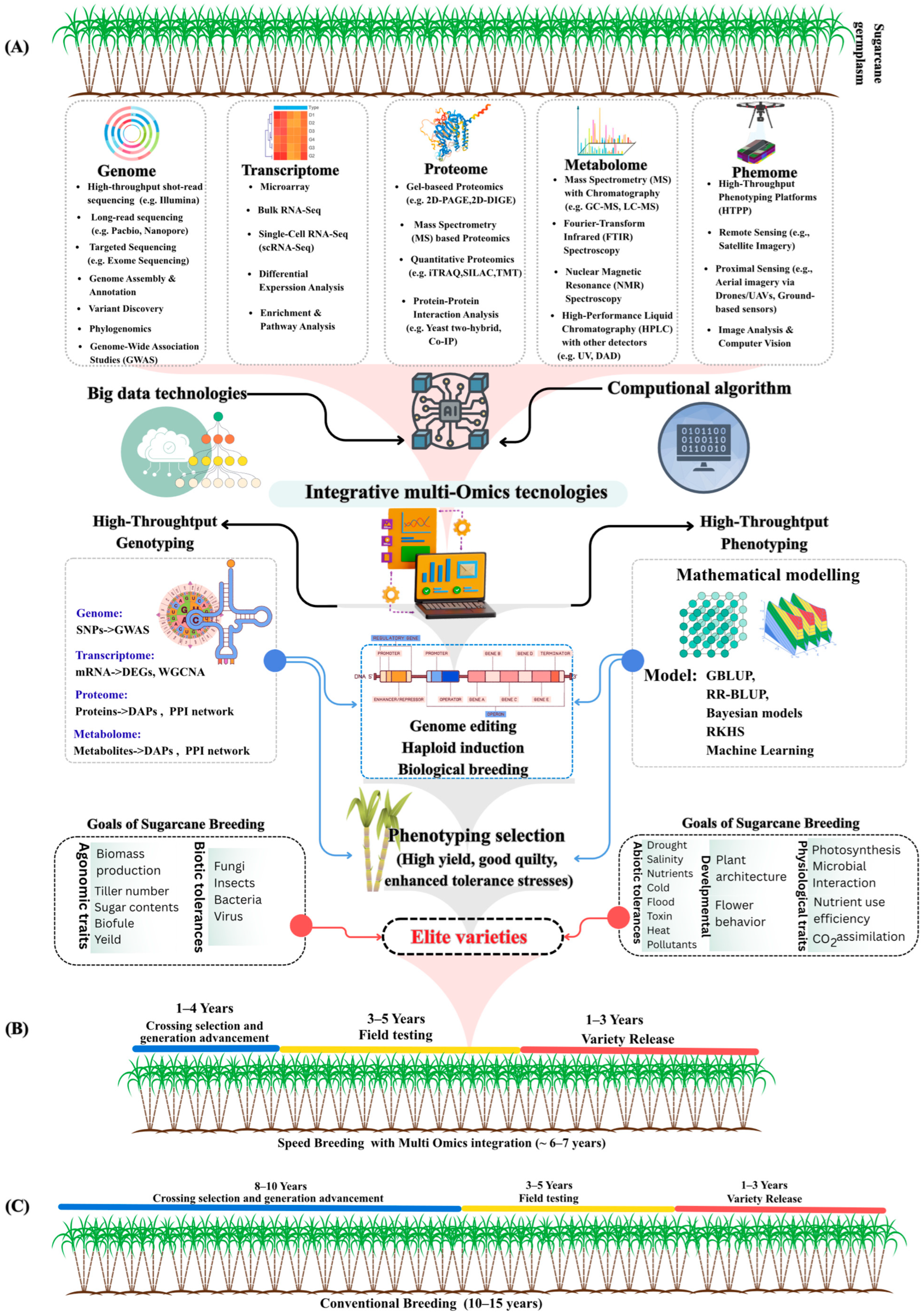

4. Multi-Omics Technology

4.1. Transcriptomics

4.2. Proteomics

4.3. Metabolomics

4.4. Phenomics

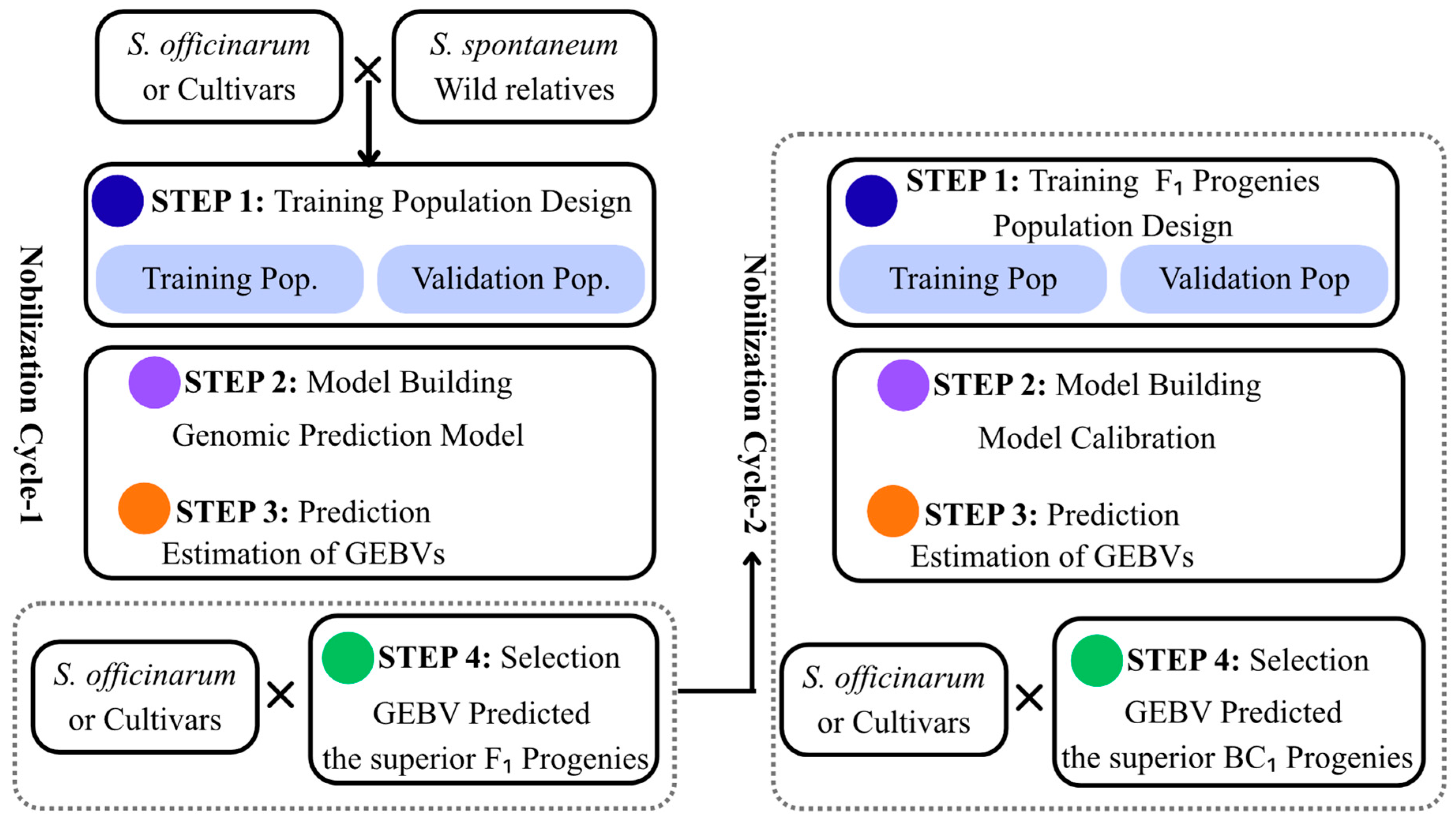

5. Genomic Selection (GS)

Applications of Genomic Selection

6. Sugarcane Genetic Engineering

6.1. Applications of Transgenes

6.2. Applications of RNA Interference (RNAi)

6.3. Sugarcane Gene Editing

7. Discussion and Future Directions

7.1. Achievements and Applications

7.2. Challenges and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ali, A.; Khan, M.; Sharif, R.; Mujtaba, M.; Gao, S.-J. Sugarcane omics: An update on the current status of research and crop improvement. Plants 2019, 8, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Chu, N.; Feng, N.; Zhou, B.; Zhou, H.; Deng, Z.; Shen, X.; Zheng, D. Global responses of autopolyploid sugarcane Badila (Saccharum officinarum L.) to drought stress based on comparative transcriptome and metabolome profiling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singels, A.; Jones, M.R.; Lumsden, T.G. Potential for sugarcane production under current and future climates in South Africa: Sugar and ethanol yields, and crop water use. Sugar Tech 2023, 25, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, T.; Liu, X.; Lakshmanan, P. A combined genomics and phenomics approach is needed to boost breeding in sugarcane. Plant Phenomics 2023, 5, 0074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piperidis, N.; D’Hont, A. Sugarcane genome architecture decrypted with chromosome-specific oligo probes. Plant J. 2020, 103, 2039–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Healey, A.; Garsmeur, O.; Lovell, J.; Shengquiang, S.; Sreedasyam, A.; Jenkins, J.; Plott, C.; Piperidis, N.; Pompidor, N.; Llaca, V.; et al. The complex polyploid genome architecture of sugarcane. Nature 2024, 628, 804–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandel, R.; Yang, X.; Song, J.; Wang, J. Potentials, challenges, and genetic and genomic resources for sugarcane biomass improvement. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandhu, K.S.; Shiv, A.; Kaur, G.; Meena, M.R.; Raja, A.K.; Vengavasi, K.; Mall, A.K.; Kumar, S.; Singh, P.K.; Singh, J.; et al. Integrated approach in genomic selection to accelerate genetic gain in sugarcane. Plants 2022, 11, 2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Eglinton, J.; Piperidis, G.; Atkin, F.; Morgan, T.; Parfitt, R.; Hu, F. Sugarcane breeding in Australia. Sugar Tech 2022, 24, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, M.H.P.; Resende, M.D.V.; Dias, L.A.d.S.; Barbosa, G.V.d.S.; Oliveira, R.A.d.; Peternelli, L.A.; Daros, E. Genetic improvement of sugar cane for bioenergy: The Brazilian experience in network research with RIDESA. Crop Breed. Appl. Biotechnol. 2012, 12, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cursi, D.E.; Hoffmann, H.P.; Barbosa, G.; Bressiani, J.A.; Gazaffi, R.; Chapola, R.G.; Fernandes Junior, A.; Balsalobre, T.W.A.; Diniz, C.A.; Santos, J.M.; et al. History and current status of sugarcane breeding, germplasm development and molecular genetics in Brazil. Sugar Tech 2022, 24, 112–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, N. Sugarcane varietal development programmes in India: An overview. Sugar Tech 2011, 13, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khumla, N.; Sakuanrungsirikul, S.; Punpee, P.; Hamarn, T.; Chaisan, T.; Soulard, L.; Songsri, P. Sugarcane breeding, germplasm development and supporting genetics research in Thailand. Sugar Tech 2022, 24, 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Gao, X.; Zeng, Q.; Zheng, Z.; Wu, C.; Yang, R.; Feng, X.; Wu, Z.; Fan, L.; Huang, Z. Sugarcane breeding, germplasm development and related molecular research in China. Sugar Tech 2022, 24, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdi, F.; Cao, Z.; Zhang, S.; Gan, Y.; Cai, W.; Peng, L.; Wu, Y.; Wang, W.; Yang, B. Factors affecting the production of sugarcane yield and sucrose accumulation: Suggested potential biological solutions. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1374228. [Google Scholar]

- Que, Y.; Xu, L.; Lin, J.; Ruan, M.; Zhang, M.; Chen, R. Differential protein expression in sugarcane during sugarcane-Sporisorium scitamineum interaction revealed by 2-DE and MALDI-TOF-TOF/MS. Int. J. Genom. 2011, 2011, 989016. [Google Scholar]

- Rajput, M.A.; Iqbal, O.; Syed, R.N.; Elsalahy, H.H.; Rajput, N.A.; Ahmad, S.; Khan, R.; Khanzada, M.A.; Younas, M.U.; Qasim, M.; et al. Screening of sugarcane germplasm against Sporisorium scitamineum and its effects on setts germination and tillering. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 14653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, M.; Soda, N.; Strachan, S.; Ngo, C.N.; Bhuiyan, S.A.; Shiddiky, M.J.; Ford, R. Ratoon stunting disease of sugarcane: A review emphasizing detection strategies and challenges. Phytopathology 2024, 114, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pimenta, R.J.G.; Aono, A.H.; Burbano, R.C.V.; da Silva, M.F.; dos Anjos, I.A.; de Andrade Landell, M.G.; Gonçalves, M.C.; Pinto, L.R.; de Souza, A.P. Multiomic investigation of sugarcane mosaic virus resistance in sugarcane. Crop J. 2023, 11, 1805–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagyalakshmi, K.; Viswanathan, R. Development of a scoring system for sugarcane mosaic disease and genotyping of sugarcane germplasm for mosaic viruses. Sugar Tech 2021, 23, 1105–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junaid, M.; Gokce, A. Global agricultural losses and their causes. Bull. Biol. Allied Sci. Res. 2024, 2024, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, T.H.; Tsunada, M.S.; Bassi, D.; Araújo, P.; Mattiello, L.; Guidelli, G.V.; Righetto, G.L.; Gonçalves, V.R.; Lakshmanan, P.; Menossi, M. Sugarcane water stress tolerance mechanisms and its implications on developing biotechnology solutions. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inman-Bamber, N.; Smith, D.M. Water relations in sugarcane and response to water deficits. Field Crops Res. 2005, 92, 185–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava, P.; Kumar, R. Soil salinity: A serious environmental issue and plant growth promoting bacteria as one of the tools for its alleviation. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2015, 22, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomathi, R.; Gururaja Rao, P.; Chandran, K.; Selvi, A. Adaptive responses of sugarcane to waterlogging stress: An over view. Sugar Tech 2015, 17, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, Y.; Wei, A.; Wang, Z.; Huang, H.; Huang, Q.; Yang, L.; Gao, Y.; Zhu, G.; Liu, Q.; et al. Integrated transcriptomic and proteomic analyses of two sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum Linn.) varieties differing in their lodging tolerance. BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, M.R.; Kumar, R.; Chinnaswamy, A.; Karuppaiyan, R.; Kulshreshtha, N.; Ram, B. Current breeding and genomic approaches to enhance the cane and sugar productivity under abiotic stress conditions. 3 Biotech 2020, 10, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garsmeur, O.; Droc, G.; Antonise, R.; Grimwood, J.; Potier, B.; Aitken, K.; Jenkins, J.; Martin, G.; Charron, C.; Hervouet, C.; et al. A mosaic monoploid reference sequence for the highly complex genome of sugarcane. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Huang, J.; Zhang, S.; Yao, W.; Yu, Z.; Deng, Z.; Yu, J.; Kong, W.; Yu, X.; et al. A chromosomal-scale genome assembly of modern cultivated hybrid sugarcane provides insights into origination and evolution. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 3041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Shang, L.; Zhu, Q.-H.; Fan, L.; Guo, L. Twenty years of plant genome sequencing: Achievements and challenges. Trends Plant Sci. 2022, 27, 391–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aitken, K.; Farmer, A.; Berkman, P.; Muller, C.; Wei, X.; Demano, E.; Jackson, P.; Magwire, M.; Dietrich, B.; Kota, R. Generation of a 345K sugarcane SNP chip. In Proceedings of the International Society of Sugar Cane Technologists, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 5–8 December 2016; pp. 1165–1172. [Google Scholar]

- Razzaq, A.; Sadia, B.; Raza, A.; Khalid Hameed, M.; Saleem, F. Metabolomics: A way forward for crop improvement. Metabolites 2019, 9, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthamilarasan, M.; Singh, N.K.; Prasad, M. Multi-omics approaches for strategic improvement of stress tolerance in underutilized crop species: A climate change perspective. Adv. Genet. 2019, 103, 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Saand, M.A.; Huang, L.; Abdelaal, W.B.; Zhang, J.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Sirohi, M.H.; Wang, F. Applications of multi-omics technologies for crop improvement. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 563953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLoughlin, F.; Augustine, R.C.; Marshall, R.S.; Li, F.; Kirkpatrick, L.D.; Otegui, M.S.; Vierstra, R.D. Maize multi-omics reveal roles for autophagic recycling in proteome remodelling and lipid turnover. Nat. Plants 2018, 4, 1056–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Wang, K.; Chen, Z.; Cao, Y.; Gao, Q.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Lu, H.; Du, H.; Lu, M.; et al. MBKbase for rice: An integrated omics knowledgebase for molecular breeding in rice. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, D1085–D1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchida, K.; Sawada, Y.; Ochiai, K.; Sato, M.; Inaba, J.; Hirai, M.Y. Identification of a unique type of isoflavone O-methyltransferase, GmIOMT1, based on multi-omics analysis of soybean under biotic stress. Plant Cell Physiol. 2020, 61, 1974–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Wang, M.; Wu, J.; Guo, W.; Chen, Y.; Li, G.; Wang, Y.; Shi, W.; Xia, G.; Fu, D.; et al. WheatOmics: A platform combining multiple omics data to accelerate functional genomics studies in wheat. Mol. Plant 2021, 14, 1965–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raza, A.; Tabassum, J.; Zahid, Z.; Charagh, S.; Bashir, S.; Barmukh, R.; Khan, R.S.A.; Barbosa, F., Jr.; Zhang, C.; Chen, H.; et al. Advances in “omics” approaches for improving toxic metals/metalloids tolerance in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 12, 794373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.; Jackson, P.; Berding, N.; Inman-Bamber, G. Conventional breeding practices within the Australian sugarcane breeding program. In Proceedings of the Australian Society of Sugar Cane Technologists, Cairns, QE, Australia, 8–11 May 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Khaiyam, M.; Islam, M.; Ganapati, R.; Uddin, M.; Hossain, M. Suitability of newly released sugarcane varieties in farmers field condition under high ganges river floodplain of Bangladesh. Int. J. Plant Biol. Res. 2018, 6, 1086. [Google Scholar]

- Azim, M.A.; Mahmud, K.; Islam, N.; Rahman, M.M.; Islam, M.T.; Hossain, A.E.; Bhuiyan, S.A. History and current status of sugarcane breeding, germplasm development and molecular approaches in Bangladesh. Sugar Tech 2024, 26, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazaffi, R.; Cursi, D.E.; Chapola, R.G.; Santos, J.; Fernandes, A., Jr.; Carneiro, M.S.; Barbosa, G.; Hoffmann, H.P. RB varieties: A major contribution to the sugarcane industry in Brazil. In Proceedings of the International Society of Sugar Cane Technologists, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 5–8 December 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Q.; Li, A.; Zhao, P.; Xia, H.; Zhang, Y.; Que, Y. Theory to practice: A success in breeding sugarcane variety YZ08–1609 known as the King of Sugar. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1413108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Govindaraju, M. Sugarcane production in China. In Sugarcane-Technology and Research; InthOpen: London, UK, 2018; Volume 49. [Google Scholar]

- La, O.M.; Perera, M.F.; Bertani, R.P.; Acevedo, R.; Arias, M.E.; Casas, M.A.; Pérez, J.; Puchades, Y.; Rodríguez, E.; Alfonso, I.; et al. An overview of sugarcane brown rust in Cuba. Sci. Agric. 2018, 75, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram, B.; Karuppaiyan, R.; Hemaprabha, G. Sugarcane breeding. In Fundamentals of Field Crop Breeding; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 499–570. [Google Scholar]

- Ram, B.; Hemaprabha, G.; Singh, B.; Appunu, C. History and current status of sugarcane breeding, germplasm development and molecular biology in India. Sugar Tech 2022, 24, 4–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Rivera, N.; Rodríguez, L.D.A.; Enríquez, R.V.; Castillo, M.A.; Herrera, S.A. The Mexican sugarcane industry: Overview, constraints, current status and long-term trends. Sugar Tech 2012, 14, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavin-Castañeda, J.; Sentíes-Herrera, H.E.; Trejo-Téllez, L.I.; Bello-Bello, J.-J.; Hidalgo-Contreras, J.V.; Gómez-Merino, F.C. Advances in the selection program of sugarcane (Saccharum spp.) varieties in the Colegio de Postgraduados. Agro Product. 2020, 13, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.U.; Muddasar, M.A.; Fiaz, N.; Afzal, M.S.; Sikandar, Z.; Shafique, M.; Hussain, S.S.; Hussain, F.; Ahmad, M.F.; Yasin, M.; et al. Unlocking commercial potential: CPF 249, a medium-maturing sugarcane variety for Punjab. Pak. J. Biotechnol. 2024, 21, 501–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luzaran, R.T.; Engle, L.M.; Villariez, H.P.; Oquias, G.B. Sugarcane breeding and germplasm development in the Philippines. Sugar Tech 2022, 24, 210–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M. Conventional sugarcane breeding in South Africa: Progress and future prospects. Am. J. Plant Sci. 2013, 4, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravois, K.; Bischoff, K.; Pontif, M.; LaBorde, C.; Hoy, J.; Reagan, T.; Kimbeng, C.; Legendre, B.; Hawkins, G.; Sexton, D.; et al. Registration of ‘L 01–299’sugarcane. J. Plant Regist. 2011, 5, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tew, T.; Dufrene, E.; Cobill, R.; Garrison, D.; White, W.; Grisham, M.; Pan, Y.-B.; Legendre, B.; Richard, E., Jr.; Miller, J.D. Registration of ‘HoCP 91–552’sugarcane. J. Plant Regist. 2011, 5, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, G.M.; Van Sluys, M.-A.; Lembke, C.G.; Lee, H.; Margarido, G.R.A.; Hotta, C.T.; Gaiarsa, J.W.; Diniz, A.L.; Oliveira, M.d.M.; Ferreira, S.d.S.; et al. Assembly of the 373k gene space of the polyploid sugarcane genome reveals reservoirs of functional diversity in the world’s leading biomass crop. GigaScience 2019, 8, giz129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asano, T.; Tsudzuki, T.; Takahashi, S.; Shimada, H.; Kadowaki, K.-I. Complete nucleotide sequence of the sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum) chloroplast genome: A comparative analysis of four monocot chloroplast genomes. DNA Res. 2004, 11, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calsa Júnior, T.; Carraro, D.M.; Benatti, M.R.; Barbosa, A.C.; Kitajima, J.P.; Carrer, H. Structural features and transcript-editing analysis of sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum L.) chloroplast genome. Curr. Genet. 2004, 46, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Setta, N.; Monteiro-Vitorello, C.B.; Metcalfe, C.J.; Cruz, G.M.Q.; Del Bem, L.E.; Vicentini, R.; Nogueira, F.T.S.; Campos, R.A.; Nunes, S.L.; Turrini, P.C.G.; et al. Building the sugarcane genome for biotechnology and identifying evolutionary trends. BMC Genom. 2014, 15, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Tang, H.; Zhang, Q.; Hua, X.; Ma, X.; Zhu, F.; Jones, T.; Zhu, X.; Bowers, J.; et al. Allele-defined genome of the autopolyploid sugarcane Saccharum spontaneum L. Nat. Genet. 2018, 50, 1565–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shearman, J.R.; Pootakham, W.; Sonthirod, C.; Naktang, C.; Yoocha, T.; Sangsrakru, D.; Jomchai, N.; Tongsima, S.; Piriyapongsa, J.; Ngamphiw, C.; et al. A draft chromosome-scale genome assembly of a commercial sugarcane. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 20474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Qi, Y.; Pan, H.; Tang, H.; Wang, G.; Hua, X.; Wang, Y.; Lin, L.; Li, Z.; Li, Y.; et al. Genomic insights into the recent chromosome reduction of autopolyploid sugarcane Saccharum spontaneum. Nat. Genet. 2022, 54, 885–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kui, L.; Majeed, A.; Wang, X.; Yang, Z.; Chen, J.; He, L.; Di, Y.; Li, X.; Qian, Z.; Jiao, Y.; et al. A chromosome-level genome assembly for Erianthus fulvus provides insights into its biofuel potential and facilitates breeding for improvement of sugarcane. Plant Commun. 2023, 4, 100562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Qi, Y.; Hua, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, B.; Qi, Y.; Huang, Y.; Yu, Z.; Gao, R.; Zhang, Y.; et al. The highly allo-autopolyploid modern sugarcane genome and very recent allopolyploidization in Saccharum. Nat. Genet. 2025, 57, 242–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, D.; Rennya, P.; Mallavarapu, M.D.; Panigrahi, R.C.; Patel, H.K. Integrating pan-omics data in a systems approach for crop improvement: Opportunities and challenges. In Omics Technologies for Sustainable Agriculture and Global Food Security (Vol II); Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 215–246. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, S.; Jackson, P.; Wei, X.; Ross, E.M.; Aitken, K.; Deomano, E.; Atkin, F.; Hayes, B.J.; Voss-Fels, K.P. Accelerating genetic gain in sugarcane breeding using genomic selection. Agronomy 2020, 10, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, U.; Li, X.; Fan, Y.; Chang, W.; Niu, Y.; Li, J.; Qu, C.; Lu, K. Multi-omics revolution to promote plant breeding efficiency. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1062952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, B.J.; Wei, X.; Joyce, P.; Atkin, F.; Deomano, E.; Yue, J.; Nguyen, L.; Ross, E.M.; Cavallaro, T.; Aitken, K.S.; et al. Accuracy of genomic prediction of complex traits in sugarcane. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2021, 134, 1455–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.S.; McCord, P.H.; Olatoye, M.O.; Qin, L.; Sood, S.; Lipka, A.E.; Todd, J.R. Experimental evaluation of genomic selection prediction for rust resistance in sugarcane. Plant Genome 2021, 14, e20148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agisha, V.; Ashwin, N.; Vinodhini, R.; Nalayeni, K.; Ramesh Sundar, A.; Malathi, P.; Viswanathan, R. Transcriptome analysis of sugarcane reveals differential switching of major defense signaling pathways in response to Sporisorium scitamineum isolates with varying virulent attributes. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 969826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Fang, W.; Yan, J.; Yan, H.; Lei, J.; Qiu, L.; Srithawong, S.; Li, D.; Luo, T.; Zhou, H.; et al. Comparative Multi-Omics Insights into Flowering-Associated Sucrose Accumulation in Contrasting Sugarcane Cultivars. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahadevaiah, C.; Appunu, C.; Aitken, K.; Suresha, G.S.; Vignesh, P.; Mahadeva Swamy, H.K.; Valarmathi, R.; Hemaprabha, G.; Alagarasan, G.; Ram, B. Genomic selection in sugarcane: Current status and future prospects. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 708233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, S.; Wei, X.; Joyce, P.; Atkin, F.; Deomano, E.; Sun, Y.; Nguyen, L.T.; Ross, E.M.; Cavallaro, T.; Aitken, K.S.; et al. Improved genomic prediction of clonal performance in sugarcane by exploiting non-additive genetic effects. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2021, 134, 2235–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, S.; Basnayake, J.; Wei, X.; Lakshmanan, P. High-throughput phenotyping of indirect traits for early-stage selection in sugarcane breeding. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 2952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Som-ard, J.; Hossain, M.D.; Ninsawat, S.; Veerachitt, V. Pre-harvest sugarcane yield estimation using UAV-based RGB images and ground observation. Sugar Tech 2018, 20, 645–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Robson, A.J. A novel approach for sugarcane yield prediction using landsat time series imagery: A case study on Bundaberg region. Adv. Remote Sens. 2016, 5, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiessl, S.V.; Quezada-Martinez, D.; Orantes-Bonilla, M.; Snowdon, R.J. Transcriptomics reveal high regulatory diversity of drought tolerance strategies in a biennial oil crop. Plant Sci. 2020, 297, 110515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contiliani, D.F.; Nebó, J.F.C.d.O.; Ribeiro, R.V.; Landell, M.G.d.A.; Pereira, T.C.; Ming, R.; Figueira, A.; Creste, S. Drought-triggered leaf transcriptional responses disclose key molecular pathways underlying leaf water use efficiency in sugarcane (Saccharum spp.). Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1182461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Yin, S.; Wei, Y.; Chen, B.; Li, W. Transcriptome and WGCNA analysis revealed the molecular mechanism of drought resistance in new sugarcane varieties. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1687280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunavath, A.; Amaresh; Murugan, N.; Keerthana, S.; Kumari, S.; Singaravelu, B.; Sundar, A.R.; Manimekalai, R. Transcription factors in plant biotic and abiotic stress responses: Potentials and prospects in sugarcane. Trop. Plant Biol. 2025, 18, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Li, J.; Song, Q.; Cheng, Q.; Tan, Q.; Zhou, Q.; Nong, Z.; Lv, P. Transcriptome and WGCNA reveal hub genes in sugarcane tiller seedlings in response to drought stress. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 12823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contiliani, D.F.; de Oliveira Nebó, J.F.C.; Ribeiro, R.V.; Andrade, L.M.; Peixoto Júnior, R.F.; Lembke, C.G.; Machado, R.S.; Silva, D.N.; Belloti, M.; de Souza, G.M.; et al. Leaf transcriptome profiling of contrasting sugarcane genotypes for drought tolerance under field conditions. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 9153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.-W.; Benatti, T.R.; Marconi, T.; Yu, Q.; Solis-Gracia, N.; Mora, V.; Da Silva, J.A. Cold responsive gene expression profiling of sugarcane and Saccharum spontaneum with functional analysis of a cold inducible Saccharum homolog of NOD26-like intrinsic protein to salt and water stress. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0125810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Song, X.; Li, Y.; Qin, Z.; Li, D.; Chen, R.; Zhou, Z.; Deng, Y.; et al. Integration of transcriptional and post-transcriptional analysis revealed the early response mechanism of sugarcane to cold stress. Front. Genet. 2021, 11, 581993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, S.; Muhammad, K.; Novaes, E.; Que, Y.; Din, A.; Islam, M.; Porto, A.; Inamullah; Sajid, M.; Ullah, N.; et al. Expression analysis of transcription factors in sugarcane during cold stress. Braz. J. Biol. 2021, 83, e242603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiande, M.; Altpeter, F. Comparing four heat-inducible promoters in stably transformed sugarcane regarding spatial and temporal control of transgene expression reveals candidates to drive stem preferred transgene expression. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1709171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raju, G.; Shanmugam, K.; Kasirajan, L. High-throughput sequencing reveals genes associated with high-temperature stress tolerance in sugarcane. 3 Biotech 2020, 10, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Que, Y.; Su, Y.; Guo, J.; Wu, Q.; Xu, L. A global view of transcriptome dynamics during Sporisorium scitamineum challenge in sugarcane by RNA-Seq. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e106476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casu, R.E.; Rae, A.L.; Nielsen, J.M.; Perroux, J.M.; Bonnett, G.D.; Manners, J.M. Tissue-specific transcriptome analysis within the maturing sugarcane stalk reveals spatial regulation in the expression of cellulose synthase and sucrose transporter gene families. Plant Mol. Biol. 2015, 89, 607–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, X.; Zeng, Q.; Chen, X.; Shan, M.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, N.; Huang, Y.; Wu, J. Full-length transcriptome integrated with RNA-seq reveals potassium deficiency stress-regulated key pathways and time-specific responsive genes in sugarcane roots. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 225, 120527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, J.G.; Calderan-Rodrigues, M.J.; de Moraes, F.E.; Cataldi, T.R.; Jamet, E.; Labate, C.A. Cell wall proteome of sugarcane young and mature leaves and stems. Proteomics 2018, 18, 1700129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnabas, L.; Ashwin, N.; Kaverinathan, K.; Trentin, A.R.; Pivato, M.; Sundar, A.R.; Malathi, P.; Viswanathan, R.; Rosana, O.; Neethukrishna, K.; et al. Proteomic analysis of a compatible interaction between sugarcane and Sporisorium scitamineum. Proteomics 2016, 16, 1111–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khueychai, S.; Jangpromma, N.; Daduang, S.; Jaisil, P.; Lomthaisong, K.; Dhiravisit, A.; Klaynongsruang, S. Comparative proteomic analysis of leaves, leaf sheaths, and roots of drought-contrasting sugarcane cultivars in response to drought stress. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2015, 37, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvato, F.; Loziuk, P.; Kiyota, E.; Daneluzzi, G.S.; Araújo, P.; Muddiman, D.C.; Mazzafera, P. Label-free quantitative proteomics of enriched nuclei from sugarcane (Saccharum ssp) stems in response to drought stress. Proteomics 2019, 19, 1900004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budzinski, I.G.F.; de Moraes, F.E.; Cataldi, T.R.; Franceschini, L.M.; Labate, C.A. Network analyses and data integration of proteomics and metabolomics from leaves of two contrasting varieties of sugarcane in response to drought. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murad, A.M.; Molinari, H.B.C.; Magalhaes, B.S.; Franco, A.C.; Takahashi, F.S.C.; de Oliveira-, N.G.; Franco, O.L.; Quirino, B.F. Physiological and proteomic analyses of Saccharum spp. grown under salt stress. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e98463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, C.M.; Pestana-Calsa, M.C.; Gozzo, F.C.; Mansur Custodio Nogueira, R.J.; Menossi, M.; Junior, T.C. Differentially delayed root proteome responses to salt stress in sugar cane varieties. J. Proteome Res. 2013, 12, 5681–5695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passamani, L.Z.; Barbosa, R.R.; Reis, R.S.; Heringer, A.S.; Rangel, P.L.; Santa-Catarina, C.; Grativol, C.; Veiga, C.F.; Souza-Filho, G.A.; Silveira, V. Salt stress induces changes in the proteomic profile of micropropagated sugarcane shoots. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0176076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Xu, L.; Wang, Z.; Peng, Q.; Yang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Que, Y. Comparative proteomics reveals that central metabolism changes are associated with resistance against Sporisorium scitamineum in sugarcane. BMC Genom. 2016, 17, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Song, Q.-Q.; Singh, R.K.; Li, H.-B.; Solanki, M.K.; Malviya, M.K.; Verma, K.K.; Yang, L.-T.; Li, Y.-R. Proteomic analysis of the resistance mechanisms in sugarcane during Sporisorium scitamineum infection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, J.-Y.; Ntambo, M.S.; Rott, P.C.; Fu, H.-Y.; Huang, M.-T.; Zhang, H.-L.; Gao, S.-J. Identification of differentially expressed proteins in sugarcane in response to infection by Xanthomonas albilineans using iTRAQ quantitative proteomics. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heringer, A.S.; Reis, R.S.; Passamani, L.Z.; de Souza-Filho, G.A.; Santa-Catarina, C.; Silveira, V. Comparative proteomics analysis of the effect of combined red and blue lights on sugarcane somatic embryogenesis. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2017, 39, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvato, F.; Wilson, R.; Portilla Llerena, J.P.; Kiyota, E.; Lima Reis, K.; Boaretto, L.F.; Balbuena, T.S.; Azevedo, R.A.; Thelen, J.J.; Mazzafera, P. Luxurious nitrogen fertilization of two sugar cane genotypes contrasting for lignin composition causes changes in the stem proteome related to carbon, nitrogen, and oxidant metabolism but does not alter lignin content. J. Proteome Res. 2017, 16, 3688–3703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nandini, K.; Kumar, P.S.; Sheelamary, S.; Selvi, A.; Rachel, L.V.; Indusha Yazhini, S.; Karpagam, E.; Lakshmi, K. Proteomics-Based Genetic Regulation of Sugarcane Cell Wall Biosynthesis for Bioenergy Applications. Sugar Tech 2025, 27, 1382–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorge, T.F.; Mata, A.T.; António, C. Mass spectrometry as a quantitative tool in plant metabolomics. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2016, 374, 20150370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, R.; Beale, M.; Fiehn, O.; Hardy, N.; Sumner, L.; Bino, R. Plant metabolomics: The missing link in functional genomics strategies. Plant Cell 2002, 14, 1437–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glassop, D.; Roessner, U.; Bacic, A.; Bonnett, G.D. Changes in the sugarcane metabolome with stem development. Are they related to sucrose accumulation? Plant Cell Physiol. 2007, 48, 573–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thangavel, S.; Subramanian, M.; Perumal Thirugnanasambandam, P.; Gunasekaran, A.; Ramanathan, V.; Chinnaswamy, A. Integrative Metabolome Profiling and Docking Study of Sugar-Related Metabolites in Lytic Vacuoles of Mature Sugarcane Stem. Trop. Plant Biol. 2025, 18, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leme, G.M.; Coutinho, I.D.; Creste, S.; Hojo, O.; Carneiro, R.L.; da Silva Bolzani, V.; Cavalheiro, A.J. HPLC-DAD method for metabolic fingerprinting of the phenotyping of sugarcane genotypes. Anal. Methods 2014, 6, 7781–7788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bini, A.P.; Rossi, G.D.; Poeschl, Y.; Serra, M.C.D.; Camargo, L.E.A.; Monteiro-Vitorello, C.B.; Van Sluys, M.-A.; van Dam, N.M.; Uthe, H.; Creste, S. Molecular, biochemical and metabolomics analyses reveal constitutive and pathogen-induced defense responses of two sugarcane contrasting genotypes against leaf scald disease. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2023, 203, 108033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaker, P.D.; Peters, L.P.; Cataldi, T.R.; Labate, C.A.; Caldana, C.; Monteiro-Vitorello, C.B. Metabolome dynamics of smutted sugarcane reveals mechanisms involved in disease progression and whip emission. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves, M.C.; Vega, J.; Oliveira, J.G.; Gomes, M. Sugarcane yellow leaf virus infection leads to alterations in photosynthetic efficiency and carbohydrate accumulation in sugarcane leaves. Fitopatol. Bras. 2005, 30, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Song, Q.; Shuai, L.; Htun, R.; Malviya, M.K.; Li, Y.; Liang, Q.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, F. Metabolic and proteomic analysis of nitrogen metabolism mechanisms involved in the sugarcane–Fusarium verticillioides interaction. J. Plant Physiol. 2020, 251, 153207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Silva, J.J.; De Abreu, L.G.; Ferrari, A.J.; De Carvalho, L.M.; Grandis, A.; Buckeridge, M.S.; Fill, T.P.; Pereira, G.A.; Carazzolle, M.F. Diurnal metabolism of energy-cane and sugarcane: A metabolomic and non-structural carbohydrate analysis. Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 202, 117056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, H.; Xie, L.; Wang, X.; Li, X.; He, L.; Li, F. Metabolomic Analysis Revealed the Differences in Metabolites Between Three Different Sugarcane Stems and Leaves. Metabolites 2025, 15, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, C.; Ono, H. Metabolomic Variation in Sugarcane Maturation Under a Temperate Climate. Metabolites 2025, 15, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furbank, R.T.; Jimenez-Berni, J.A.; George-Jaeggli, B.; Potgieter, A.B.; Deery, D.M. Field crop phenomics: Enabling breeding for radiation use efficiency and biomass in cereal crops. New Phytol. 2019, 223, 1714–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awada, L.; Phillips, P.W.; Bodan, A.M. The evolution of plant phenomics: Global insights, trends, and collaborations (2000–2021). Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1410738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Feng, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, J.; Doonan, J.H.; Batchelor, W.D.; Xiong, L.; Yan, J. Crop phenomics and high-throughput phenotyping: Past decades, current challenges, and future perspectives. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 187–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wei, J.; Li, R.; Qu, H.; Chater, J.M.; Ma, R.; Li, Y.; Xie, W.; Jia, Z. Identification of optimal prediction models using multi-omic data for selecting hybrid rice. Heredity 2019, 123, 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Xu, Y.; Gong, L.; Zhang, Q. Metabolomic prediction of yield in hybrid rice. Plant J. 2016, 88, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Campbell, M.T.; Yeats, T.H.; Zheng, X.; Runcie, D.E.; Covarrubias-Pazaran, G.; Broeckling, C.; Yao, L.; Caffe-Treml, M.; Gutiérrez, L.; et al. Multi-omics prediction of oat agronomic and seed nutritional traits across environments and in distantly related populations. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2021, 134, 4043–4054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissbrod, O.; Geiger, D.; Rosset, S. Multikernel linear mixed models for complex phenotype prediction. Genome Res. 2016, 26, 969–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Carbonetto, P.; Stephens, M. Polygenic modeling with Bayesian sparse linear mixed models. PLoS Genet. 2013, 9, e1003264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Wen, Y. A penalized linear mixed model with generalized method of moments for prediction analysis on high-dimensional multi-omics data. Brief. Bioinform. 2022, 23, bbac193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, P.; Wang, J.; Guo, X.; Yang, W.; Zhao, C. High-throughput phenotyping: Breaking through the bottleneck in future crop breeding. Crop J. 2021, 9, 633–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanut, B.; Waranusast, R.; Riyamongkol, P. High accuracy pre-harvest sugarcane yield forecasting model utilizing drone image analysis, data mining, and reverse design method. Agriculture 2021, 11, 682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanches, G.M.; Duft, D.G.; Kölln, O.T.; Luciano, A.C.d.S.; De Castro, S.G.Q.; Okuno, F.M.; Franco, H.C.J. The potential for RGB images obtained using unmanned aerial vehicle to assess and predict yield in sugarcane fields. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2018, 39, 5402–5414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahi, D.; Todd, J.; Gravois, K.; Hale, A.; Blanchard, B.; Kimbeng, C.; Pontif, M.; Baisakh, N. Exploiting historical agronomic data to develop genomic prediction strategies for early clonal selection in the Louisiana sugarcane variety development program. Plant Genome 2025, 18, e20545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calus, M.P.; Veerkamp, R.F. Accuracy of multi-trait genomic selection using different methods. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2011, 43, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gouy, M.; Rousselle, Y.; Bastianelli, D.; Lecomte, P.; Bonnal, L.; Roques, D.; Efile, J.-C.; Rocher, S.; Daugrois, J.; Toubi, L.; et al. Experimental assessment of the accuracy of genomic selection in sugarcane. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2013, 126, 2575–2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sariful, I.M.; Islam, M.S.; McCord, P.; Read, Q.D.; Qin, L.; Lipka, A.E.; Sood, S.; Todd, J.; Olatoye, M. Accuracy of Genomic Prediction of Yield and Sugar Traits in Saccharum spp. Hybrids. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, A.; Deo, J.; Deomano, E.; Wei, X.; Jackson, P.; Aitken, K.S.; Manimekalai, R.; Mohanraj, K.; Hemaprabha, G.; Ram, B.; et al. Combining genomic selection with genome-wide association analysis identified a large-effect QTL and improved selection for red rot resistance in sugarcane. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1021182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deomano, E.; Jackson, P.; Wei, X.; Aitken, K.; Kota, R.; Pérez-Rodríguez, P. Genomic prediction of sugar content and cane yield in sugar cane clones in different stages of selection in a breeding program, with and without pedigree information. Mol. Breed. 2020, 40, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Powell, O.; Dinglasan, E.; Ross, E.M.; Yadav, S.; Wei, X.; Atkin, F.; Deomano, E.; Hayes, B.J. Genomic prediction with machine learning in sugarcane, a complex highly polyploid clonally propagated crop with substantial non-additive variation for key traits. Plant Genome 2023, 16, e20390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo-Meagher, M.; Irvine, J. Herbicide resistant transgenic sugarcane plants containing the bar gene. Crop Sci. 1996, 36, 1367–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manickavasagam, M.; Ganapathi, A.; Anbazhagan, V.; Sudhakar, B.; Selvaraj, N.; Vasudevan, A.; Kasthurirengan, S. Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation and development of herbicide-resistant sugarcane (Saccharum species hybrids) using axillary buds. Plant Cell Rep. 2004, 23, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basso, M.F.; da Cunha, B.A.D.B.; Ribeiro, A.P.; Martins, P.K.; de Souza, W.R.; de Oliveira, N.G.; Nakayama, T.J.; Augusto das Chagas Noqueli Casari, R.; Santiago, T.R.; Vinecky, F.; et al. Improved genetic transformation of sugarcane (Saccharum spp.) embryogenic callus mediated by Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Curr. Protoc. Plant Biol. 2017, 2, 221–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.Z.; Yang, B.P.; Feng, X.Y.; Cao, Z.Y.; Feng, C.L.; Wang, J.G.; Xiong, G.R.; Shen, L.B.; Zeng, J.; Zhao, T.T.; et al. Development and characterization of transgenic sugarcane with insect resistance and herbicide tolerance. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Javed, T.; Shen, L.; Sun, T.; Yang, B.; Zhang, S. Establishment of an efficient sugarcane transformation system via herbicide-resistant CP4-EPSPS gene selection. Plants 2024, 13, 852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hotta, C.T.; Lembke, C.G.; Domingues, D.S.; Ochoa, E.A.; Cruz, G.M.; Melotto-Passarin, D.M.; Marconi, T.G.; Santos, M.O.; Mollinari, M.; Margarido, G.R.; et al. The biotechnology roadmap for sugarcane improvement. Trop. Plant Biol. 2010, 3, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, K.K.; Song, X.-P.; Budeguer, F.; Nikpay, A.; Enrique, R.; Singh, M.; Zhang, B.-Q.; Wu, J.-M.; Li, Y.-R. Genetic engineering: An efficient approach to mitigating biotic and abiotic stresses in sugarcane cultivation. Plant Signal. Behav. 2022, 17, 2108253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arencibia, A.; Vázquez, R.I.; Prieto, D.; Téllez, P.; Carmona, E.R.; Coego, A.; Hernández, L.; De la Riva, G.A.; Selman-Housein, G. Transgenic sugarcane plants resistant to stem borer attack. Mol. Breed. 1997, 3, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Yang, Y.; Wang, C.; Guo, J.; Zhou, D.; Wu, Q.; Su, Y.; Xu, L.; Que, Y. Transgenic sugarcane with a cry1Ac gene exhibited better phenotypic traits and enhanced resistance against sugarcane borer. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0153929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Liu, X.; Gao, S.; Guo, J.; Su, Y.; Ling, H.; Wang, C.; Li, Z.; Xu, L.; Que, Y. Foreign cry1Ac gene integration and endogenous borer stress-related genes synergistically improve insect resistance in sugarcane. BMC Plant Biol. 2018, 18, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budeguer, F.; Enrique, R.; Perera, M.F.; Racedo, J.; Castagnaro, A.P.; Noguera, A.S.; Welin, B. Genetic transformation of sugarcane, current status and future prospects. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 768609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riaz, S.; Nasir, I.A.; Bhatti, M.U.; Adeyinka, O.S.; Toufiq, N.; Yousaf, I.; Tabassum, B. Resistance to Chilo infuscatellus (Lepidoptera: Pyraloidea) in transgenic lines of sugarcane expressing Bacillus thuringiensis derived Vip3A protein. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2020, 47, 2649–2658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noguera, A.S.; Enrique, R.; Ostengo, S.; Perera, M.F.; Racedo, J.; Costilla, D.; Zossi, S.; Cuenya, M.I.; Paula, M.; Welin, B. Development of the transgenic sugarcane event TUC 87-3RG resistant to glyphosate. In Proceedings of the International Society of Sugar Cane Technologists, Tucumán, Argentina, 2–5 September 2019; pp. 493–501. [Google Scholar]

- Falco, M.C.; Silva-Filho, M.C. Expression of soybean proteinase inhibitors in transgenic sugarcane plants: Effects on natural defense against Diatraea saccharalis. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2003, 41, 761–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhangsun, D.; Luo, S.; Chen, R.; Tang, K. Improved Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation of GNA transgenic sugarcane. Biologia 2007, 62, 386–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.J.; McCafferty, H.; Osterman, G.; Lim, S.; Agbayani, R.; Lehrer, A.; Schenck, S.; Komor, E. Genetic transformation with untranslatable coat protein gene of sugarcane yellow leaf virus reduces virus titers in sugarcane. Transgenic Res. 2011, 20, 503–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, W.; Ruan, M.; Qin, L.; Yang, C.; Chen, R.; Chen, B.; Zhang, M. Field performance of transgenic sugarcane lines resistant to sugarcane mosaic virus. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belintani, N.; Guerzoni, J.; Moreira, R.; Vieira, L. Improving low-temperature tolerance in sugarcane by expressing the ipt gene under a cold inducible promoter. Biol. Plant. 2012, 56, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.A.; Wu, W.; Yan, Y.; Bhuiyan, S.A. Overexpression of TERF1 in sugarcane improves tolerance to drought stress. Crop Pasture Sci. 2021, 72, 268–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinnaswamy, A.; Sakthivel, S.K.; Channappa, M.; Ramanathan, V.; Shivalingamurthy, S.G.; Peter, S.C.; Kumar, R.; Kumar, R.A.; Dhansu, P.; Meena, M.R.; et al. Overexpression of an NF-YB gene family member, EaNF-YB2, enhances drought tolerance in sugarcane (Saccharum Spp. Hybrid). BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mbambalala, N.; Panda, S.K.; van der Vyver, C. Overexpression of AtBBX29 improves drought tolerance by maintaining photosynthesis and enhancing the antioxidant and osmolyte capacity of sugarcane plants. Plant Mol. Biol. Report. 2021, 39, 419–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanan, M.V.; Pushpanathan, A.; Padmanabhan, S.; Sasikumar, T.; Jayanarayanan, A.N.; Selvarajan, D.; Ramalingam, S.; Ram, B.; Chinnaswamy, A. Overexpression of Glyoxalase III gene in transgenic sugarcane confers enhanced performance under salinity stress. J. Plant Res. 2021, 134, 1083–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Appunu, C.; Krishna, S.S.; Chandar, S.H.; Valarmathi, R.; Suresha, G.S.; Sreenivasa, V.; Malarvizhi, A.; Manickavasagam, M.; Arun, M.; Kumar, R.A.; et al. Overexpression of EaALDH7, an aldehyde dehydrogenase gene from Erianthus arundinaceus enhances salinity tolerance in transgenic sugarcane (Saccharum spp. Hybrid). Plant Sci. 2024, 348, 112206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerzoni, J.T.S.; Belintani, N.G.; Moreira, R.M.P.; Hoshino, A.A.; Domingues, D.S.; Filho, J.C.B.; Vieira, L.G.E. Stress-induced Δ1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthetase (P5CS) gene confers tolerance to salt stress in transgenic sugarcane. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2014, 36, 2309–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, D.; Jeena, A.S.; Rohit; Gaur, S.; Raj, R.; Mishra, S.; Kajal; Gupta, O.P.; Meena, M.R. Advances in RNA interference for plant functional genomics: Unveiling traits, mechanisms, and future directions. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2024, 196, 5681–5710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brant, E.; Zuniga-Soto, E.; Altpeter, F. RNAi and genome editing of sugarcane: Progress and prospects. Plant J. 2025, 121, e70048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bewg, W.P.; Poovaiah, C.; Lan, W.; Ralph, J.; Coleman, H.D. RNAi downregulation of three key lignin genes in sugarcane improves glucose release without reduction in sugar production. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2016, 9, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, J.H.; Fouad, W.M.; Vermerris, W.; Gallo, M.; Altpeter, F. RNAi suppression of lignin biosynthesis in sugarcane reduces recalcitrance for biofuel production from lignocellulosic biomass. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2012, 10, 1067–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glassop, D.; Stiller, J.; Bonnett, G.D.; Grof, C.P.; Rae, A.L. An analysis of the role of the ShSUT1 sucrose transporter in sugarcane using RNAi suppression. Funct. Plant Biol. 2017, 44, 795–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Wang, J.; Kannan, B.; Koukoulidis, N.M.; Lin, Y.-H.; Altpeter, F.; Chen, L.-Q. Tonoplast sugar transporters as key drivers of sugar accumulation, a case study in sugarcane. Hortic. Res. 2025, 12, uhae312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Huang, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Lu, M.; Zhu, L.; Di, R.; Duan, Z.; Bao, Y.; Hu, Q.; Powell, C.A.; et al. Enhanced Resistance to Pokkah Boeng Disease in Sugarcane Through Host-Induced Gene Silencing Targeting FsCYP51 in Fusarium sacchari. Plant Cell Environ. 2025, 48, 3861–3874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Widyaningrum, S.; Pujiasih, D.R.; Sholeha, W.; Harmoko, R.; Sugiharto, B. Induction of resistance to sugarcane mosaic virus by RNA interference targeting coat protein gene silencing in transgenic sugarcane. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2021, 48, 3047–3054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neris, D.; Mattiello, L.; Zuñiga, G.; Purgatto, E.; Menossi, M. Reduction of ethylene biosynthesis in sugarcane induces growth and investment in the non-enzymatic antioxidant apparatus. Plant Cell Rep. 2022, 41, 979–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakthivel, S.K.; Vennapusa, A.R.; Melmaiee, K. Enhancing quality and climate resilient traits in vegetatively propagated polyploids: Transgenic and genome editing advancements, challenges and future directions. Front. Genet. 2025, 16, 1599242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atia, M.; Jiang, W.; Sedeek, K.; Butt, H.; Mahfouz, M. Crop bioengineering via gene editing: Reshaping the future of agriculture. Plant Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussin, S.H.; Liu, X.; Li, C.; Diaby, M.; Jatoi, G.H.; Ahmed, R.; Imran, M.; Iqbal, M.A. An updated overview on insights into sugarcane genome editing via CRISPR/Cas9 for sustainable production. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.H.; Altpeter, F. TALEN mediated targeted mutagenesis of the caffeic acid O-methyltransferase in highly polyploid sugarcane improves cell wall composition for production of bioethanol. Plant Mol. Biol. 2016, 92, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oz, M.T.; Altpeter, A.; Karan, R.; Merotto, A.; Altpeter, F. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated multi-allelic gene targeting in sugarcane confers herbicide tolerance. Front. Genome Ed. 2021, 3, 673566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eid, A.; Mohan, C.; Sanchez, S.; Wang, D.; Altpeter, F. Multiallelic, targeted mutagenesis of magnesium chelatase with CRISPR/Cas9 provides a rapidly scorable phenotype in highly polyploid sugarcane. Front. Genome Ed. 2021, 3, 654996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laksana, C.; Sophiphun, O.; Chanprame, S. Lignin reduction in sugarcane by performing CRISPR/Cas9 site-direct mutation of SoLIM transcription factor. Plant Sci. 2024, 340, 111987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brant, E.J.; Eid, A.; Kannan, B.; Baloglu, M.C.; Altpeter, F. The extent of multiallelic, co-editing of LIGULELESS1 in highly polyploid sugarcane tunes leaf inclination angle and enables selection of the ideotype for biomass yield. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2024, 22, 2660–2671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, M.T.; Chattha, M.U.; Khan, I.; Chattha, M.B.; Anjum, S.A.; Ahmad, S.; Kanwal, H.; Usman, S.; Hassan, M.U.; Rasheed, F.; et al. Sustainable Nitrogen Management in Sugarcane Production. In Agronomy and Horticulture Annual Volume 2025; InthOpen: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Raza, A.; Tabassum, J.; Kudapa, H.; Varshney, R.K. Can omics deliver temperature resilient ready-to-grow crops? Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2021, 41, 1209–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thingujam, D.; Gouli, S.; Cooray, S.P.; Chandran, K.B.; Givens, S.B.; Gandhimeyyan, R.V.; Tan, Z.; Wang, Y.; Patam, K.; Greer, S.A.; et al. Climate-resilient crops: Integrating AI, multi-omics, and advanced phenotyping to address global agricultural and societal challenges. Plants 2025, 14, 2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsanova, T.; Stefanova, L.; Topalova, L.; Atanasov, A.; Pantchev, I. DNA-free gene editing in plants: A brief overview. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2021, 35, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molla, K.A.; Sretenovic, S.; Bansal, K.C.; Qi, Y. Precise plant genome editing using base editors and prime editors. Nat. Plants 2021, 7, 1166–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komor, A.C.; Kim, Y.B.; Packer, M.S.; Zuris, J.A.; Liu, D.R. Programmable editing of a target base in genomic DNA without double-stranded DNA cleavage. Nature 2016, 533, 420–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hua, K.; Tao, X.; Liang, W.; Zhang, Z.; Gou, R.; Zhu, J.K. Simplified adenine base editors improve adenine base editing efficiency in rice. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2020, 18, 770–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Liu, J.; Chai, Z.; Chen, S.; Bai, Y.; Zong, Y.; Chen, K.; Li, J.; Jiang, L.; Gao, C. Generation of herbicide tolerance traits and a new selectable marker in wheat using base editing. Nat. Plants 2019, 5, 480–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhang, Y.; Yuan, S.; Su, Q.; Sun, S.; Wu, C.; Yao, W.; Han, T.; Hou, W. Target base editing in soybean using a modified CRISPR/Cas9 system. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2020, 18, 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Q.; Sretenovic, S.; Liu, S.; Tang, X.; Huang, L.; He, Y.; Liu, L.; Guo, Y.; Zhong, Z.; Liu, G.; et al. PAM-less plant genome editing using a CRISPR–SpRY toolbox. Nat. Plants 2021, 7, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veillet, F.; Kermarrec, M.-P.; Chauvin, L.; Guyon-Debast, A.; Chauvin, J.-E.; Gallois, J.-L.; Nogué, F. Prime editing is achievable in the tetraploid potato, but needs improvement. BioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, P.; Zhao, Y.; Zhou, X.; Liu, Z.; Huang, Z.; Ni, Z.; Sun, Q.; Zong, Y. Efficient and versatile multiplex prime editing in hexaploid wheat. Genome Biol. 2023, 24, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoang, B.T.L.; Fletcher, S.J.; Brosnan, C.A.; Ghodke, A.B.; Manzie, N.; Mitter, N. RNAi as a foliar spray: Efficiency and challenges to field applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Jin, H. Spray-induced gene silencing: A powerful innovative strategy for crop protection. Trends Microbiol. 2017, 25, 4–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Lu, M.; Xu, J.; Wu, F.; Jin, W. Development and application of an RNA nanostructure to induce transient RNAi in difficult transgenic plants. Biotechnol. J. 2024, 19, 2400024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kant, R.; Dasgupta, I. Gene silencing approaches through virus-based vectors: Speeding up functional genomics in monocots. Plant Mol. Biol. 2019, 100, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, S.H.; Bigham, M.; Lappe, R.R.; Chan, B.; Nagalakshmi, U.; Whitham, S.A.; Dinesh-Kumar, S.P.; Jander, G. A sugarcane mosaic virus vector for rapid in planta screening of proteins that inhibit the growth of insect herbivores. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 1713–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Country | Breeding Entities | Breeding Objectives | Typical Varieties | Disease Resistance | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | Sugar Research Australia (SRA) | Yield, sugar recovery, drought/flood resilience, and mechanization. | Q208, Q240, Q253, SRA28, SRA32 | Brown rust, smut, Pachymetra root rot, leaf scald. | [9,40] |

| Bangladesh | Bangladesh Sugarcane Research Institute (BSRI) | High sugar, early maturity, salinity tolerance, and water saving. | Isd 39, Isd 40, BSRI series | Red rot, smut, wilt. | [41,42] |

| Brazil | RIDESA (public), CTC (private) | High tonnage (TCH), sugar (ATR), energy cane, and mechanization. | RB867515, RB966928, CTC9001, CTC9003 | Smut, orange rust, brown rust, RSD. | [10,11,43] |

| China | CATAS, Provincial Institutes (i.e., GXAAS, YAAS) | High sugar, cold/frost tolerance, and mechanical suitability. | GT66, LC05-136, YZ08-1609, ROC22 (legacy) | Smut, pokkah boeng, mosaic, brown rust. | [44,45] |

| Cuba | INICA | Yield, sugar recovery, and ecological adaptability. | C86-12, C323-68, C90-317, B7274 | Brown rust, yellow rust, mosaic. | [46] |

| India | ICAR-SBI, State Universities | Red rot resistance, high sugar (early), drought/salinity. | Co 0238, Co 118, Co 15023, Co 86032 | Red rot, smut, wilt, and yellow leaf disease (YLD). | [12,47,48] |

| Mexico | Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolasy Pecuarias (INIFAP) | Sugar recovery, regional adaptability, pest resistance. | CP 72-2086, Mex 69-290, Mex 79-431, RD 7511 | Smut, rust, mosaic, Fusarium. | [49,50] |

| Pakistan | PCCC, AARI, NSTHRI | High sucrose (CCS%), drought tolerance, and water efficiency. | CPF-253, HSF-240, CP77-400, Thatta-2026 | Smut, red rot, mosaic, Pyrilla/Whitefly (pests). | [51] |

| Philippines | RA, PHILSURIN | Yield, ratoon stability, resistance to sap-sucking pests. | PHIL 99-1793, PSR 07-195, VMC 86-550 | Smut, downy mildew, rust, Red-Striped Soft-Scale Insect (RSSI). | [52] |

| South Africa | SASRI | Eldana (borer) resistance, high sugar, drought resilience. | N12, N14, N52, NCo310 (legacy) | Smut, Eldana stem borer, RSD. | [53] |

| Thailand | OCSB, Kasetsart Univ., DOA | Drought tolerance, perennial (root) strength, and high sugar. | KK3, LK92-11, K88-92, UT12 | Red rot, smut, white leaf disease. | [13] |

| United States | USDA-ARS, UF, LSU | Frost tolerance, ratoon stability, and mechanization. | L 01-299, HoCP 14-885, CP varieties | Brown/orange rust, smut, leaf scald. | [54,55] |

| Year | Milestone | Cultivar/Species | Genomic Data | Key Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | Chloroplast genome sequencing | NC0310, SP80-3280, Q155, RB867515 | 141,181–141,182 bp | High conservation; minor polymorphisms [57,58] |

| 2014 | Chloroplast genome sequencing | R570 | 1400 genes | First reference gene set; based on 317 BACs [59] |

| 2018 | Sorghum-referenced haploid assembly | R570 | 382 Mb; 25,316 genes | 17% non-colinear with sorghum [28] |

| 2018 | Whole-genome sequencing | S. spontaneum (AP85-441) | 32 chromosomes; 35,525 genes | Chromosome reduction: 10 to 8 [60] |

| 2019 | Illumina’s synthetic long-read technology | SP80-3280 | 3 Gb; 373,869 genes | 2–6 homo(eco)logs per gene [56] |

| 2022 | PacBio RSII + Hi-C | Khon Kaen 3 (KK3) | 7 Gb; 56 pseudochromosomes; 242,406 genes | First chromosome-scale assembly; recombination mapped [61] |

| 2022 | Whole-genome sequencing | S. spontaneum (Np-X) | 2.76 Gb; 40 pseudo-chromosomes; 45,014 genes | Expanded S. spontaneum data [62] |

| 2023 | Whole-genome sequencing | Erianthus rufipilus (2 accessions) | 902 Mb/856.4 Mb; 10 chromosomes each; ~33,000 gene each | First Erianthus genome [63] |

| 2024 | Haplotype-resolved sequencing | ZZ1 (Chinese hybrid) | 10.4 Gb; 114 chromosomes; 68,509 genes | Sugar genes from S. officinarum; Disease genes from S. spontaneum [29] |

| 2024 | Polyploid reference genome | R570 | 8.7 Gb; ~114 chromosomes; 194,593 genes | Resolved the Bru1 brown rust resistance locus. [6] |

| 2025 | Haplotype-resolved sequencing | XTT22 (Chinese elite cultivar) | 9.3 Gb; 97 chromosomes | Allo-autopolyploid; recent allopolyploidization; trait mapping [64] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Srithawong, S.; Fang, W.; Jing, Y.; Pholtaisong, J.; Li, D.; Khumla, N.; Sakuanrungsirikul, S.; Li, M. Sugarcane Breeding in the Genomic Era: Integrative Strategies and Emerging Technologies. Plants 2026, 15, 286. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020286

Srithawong S, Fang W, Jing Y, Pholtaisong J, Li D, Khumla N, Sakuanrungsirikul S, Li M. Sugarcane Breeding in the Genomic Era: Integrative Strategies and Emerging Technologies. Plants. 2026; 15(2):286. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020286

Chicago/Turabian StyleSrithawong, Suparat, Weikuan Fang, Yan Jing, Jatuphol Pholtaisong, Du Li, Nattapat Khumla, Suchirat Sakuanrungsirikul, and Ming Li. 2026. "Sugarcane Breeding in the Genomic Era: Integrative Strategies and Emerging Technologies" Plants 15, no. 2: 286. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020286

APA StyleSrithawong, S., Fang, W., Jing, Y., Pholtaisong, J., Li, D., Khumla, N., Sakuanrungsirikul, S., & Li, M. (2026). Sugarcane Breeding in the Genomic Era: Integrative Strategies and Emerging Technologies. Plants, 15(2), 286. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020286