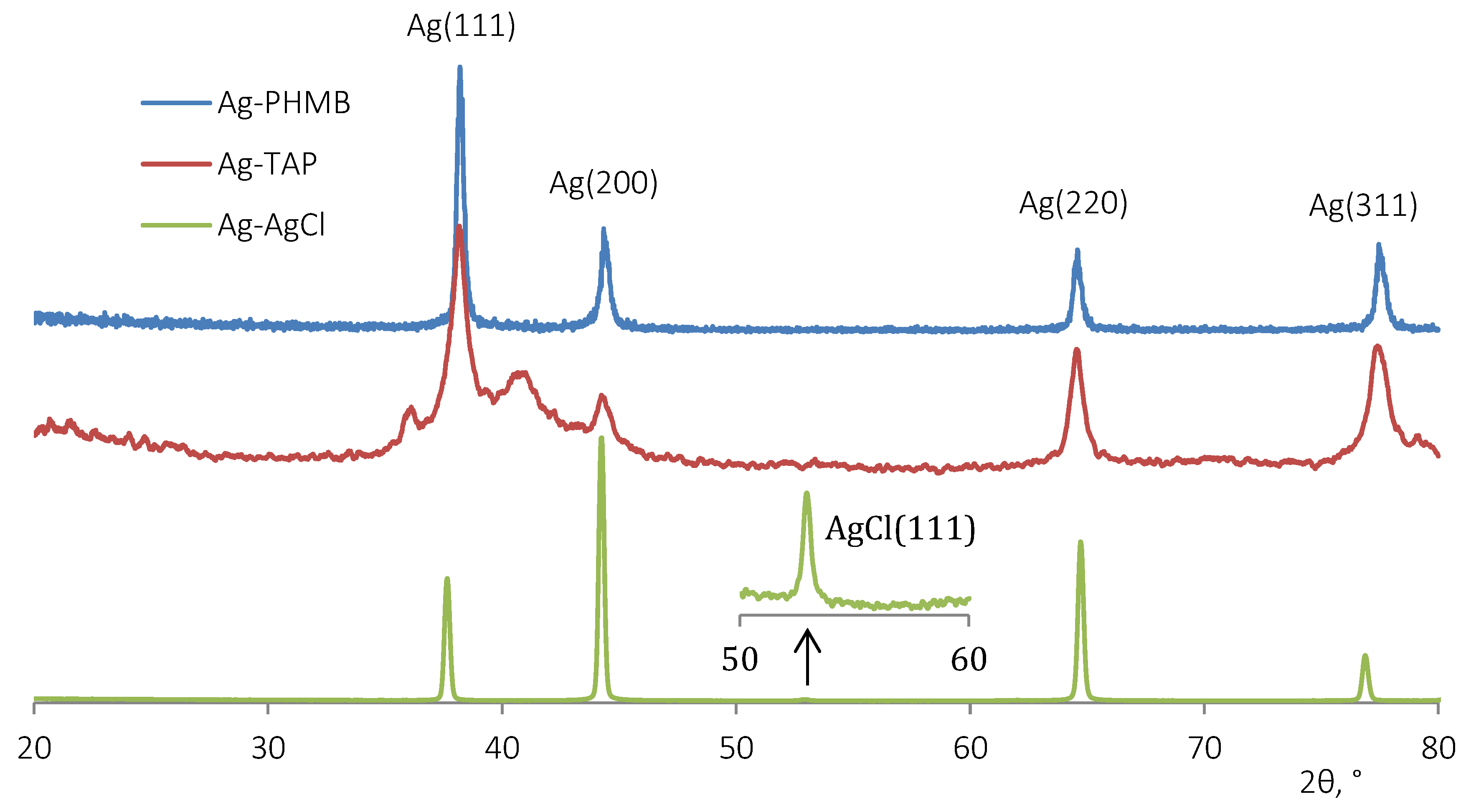

3.2. Field Trials Results

Foliar applications of AgNP dispersions had no significant effect on potato emergence, duration of the vegetative period, or timing of key phenological stages. Uniform emergence was observed across all experimental variants, including the control, with a final emergence rate of 100%.

During the growing season, natural infection caused by

A. solani (causing early blight) and

P. infestans (causing late blight) was recorded on foliage starting from the budding stage and progressing throughout the summer (

Figure 6,

Table 2). In the control plots, disease incidence remained low (<10%) during early vegetation but gradually increased in SOD, reaching moderate severity for

A. solani and high severity for

P. infestans by mid- to late season.

All AgNP treatments effectively suppressed both diseases, providing disease control efficacy of at least 60%. Notably, the dispersions exhibited particularly strong suppression of A. solani, with a success rate exceeding 80%. In contrast, the individual stabilizing agents—added to prevent nanoparticle aggregation—showed statistically significant (p < 0.05, ANOVA) 10–30% lower antifungal activity compared to the complete silver formulations, indicating that the primary protective effect is attributable to AgNPs rather than the stabilizers alone. The key role of stabilizing agents is to maintain aggregative stability of AgNP colloids during foliar treatment on potato leaves and inside the plant tissues. Also, the reduction in disease severity was statistically significant in all silver-treated plots compared to the control.

It is well established [

22,

23,

24] that AgNPs exhibit negligible intrinsic fungicidal activity at the concentrations used in the field trials. For example, in a study by Kim et al. [

24], silver nanoparticles suppressed the growth of pathogenic fungi by half starting at a concentration of about 10 ppm. In the present study, the silver dose was varied from 0.1 to 9 g/ha, which corresponded to a silver content in the spraying liquid of 0.5–45 ppm, and the silver concentration in the tissues will be significantly lower. Even at a silver content of 0.5 ppm, the disease control efficacy in all cases exceeded 60% and showed little dependence on the applied Ag input across the range of 0.1 to 9.0 g/ha (

Table 2), suggesting that, under our field conditions, AgNPs primarily acted by eliciting plant defense responses rather than by exerting direct fungicidal activity against the pathogen.

Therefore, the observed significant suppression of phytopathogens is likely attributable to an indirect, host-mediated mechanism rather than direct antimicrobial action.

Previous studies have demonstrated that both silver ions (Ag

+) and AgNPs significantly impact the plant antioxidant system [

14]. In a study by Bagherzadeh, Homaee, and Ehsanpour [

25], it was discovered that both Ag

+ and AgNPs increase total ROS content, superoxide anions, activities of SOD, CAT, ascorbate peroxidase, and glutathione reductase (GR).

Upon entering plant tissues, Ag

+ ions primarily deplete the cellular pool of reduced GSH, a crucial low-molecular-weight antioxidant involved in redox homeostasis. In higher plants, detoxification of Ag

+, Cu

2+, and other heavy metals involves two major pathways: metallothioneins (gene-encoded cysteine-rich proteins) and phytochelatins—oligopeptides enzymatically synthesized from GSH by phytochelatin synthase [

26,

27,

28].

The diversion of GSH toward phytochelatin biosynthesis compromises its availability for ROS scavenging. Glutathione plays a key role in hydrogen peroxide detoxification via the ascorbate–glutathione cycle, where it acts as a reductant for dehydroascorbate reductase (DHAR), enabling the regeneration of ascorbate. The resulting glutathione disulfide (GSSG) is reduced back to GSH by glutathione reductase (GR). Under Ag

+ stress, excessive consumption of GSH disrupts this cycle, leading to H

2O

2 accumulation and the induction of oxidative stress [

10,

11,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31].

In response, plants modulate the activity of key antioxidant enzymes. CAT, ascorbate peroxidase (APX), and guaiacol peroxidase (GPX) are widely recognized markers of oxidative stress, with their activity altered following challenges of the biotic and abiotic kind [

9].

Notably, in vitro studies show that Ag

+ and AgNPs inhibit CAT activity [

32], likely due to binding to thiol groups or disruption of the heme moiety, while exerting minimal effects on SOD [

32].

Peroxidase activity is biphasically regulated: it is promoted at low Ag concentrations (<1 mM) [

33,

34], but inhibited at higher doses [

33,

34], suggesting a hormetic response.

When applied foliarly via aqueous dispersions of functionalized AgNPs that release Ag+ gradually and at low levels, the resulting oxidative stress remains mild and transient. This suboptimal redox perturbation can act as a priming signal, enhancing plant immunity. ROS function not only as direct antimicrobial agents but also as secondary messengers in defense signaling pathways, including the activation of pathogenesis-related (PR) genes and systemic acquired resistance (SAR).

In contrast, high-dose exposure—particularly through root uptake or direct application of silver salts—overwhelms antioxidant defenses, leading to phytotoxicity, growth inhibition, and metabolic dysfunction.

Importantly, controlled oxidative stress contributes to the initiation of the hypersensitive-like response, which restricts pathogen colonization. The cytotoxicity of ROS toward phytopathogens, combined with localized cell death, enhances disease resistance in plants capable of maintaining physiological balance. Thus, the targeted modulation of oxidative stress by biocompatible AgNPs may represent a promising strategy to prime plant immunity against pathogens, provided the dose and delivery system ensure minimal phytotoxicity.

In all experimental conditions, AgNPs acted as elicitors—i.e., they triggered plant defense responses upon entry into plant tissues, including a transient burst of ROS. This response is consistent with the induction of oxidative stress as a signal for defense activation rather than direct pathogen toxicity.

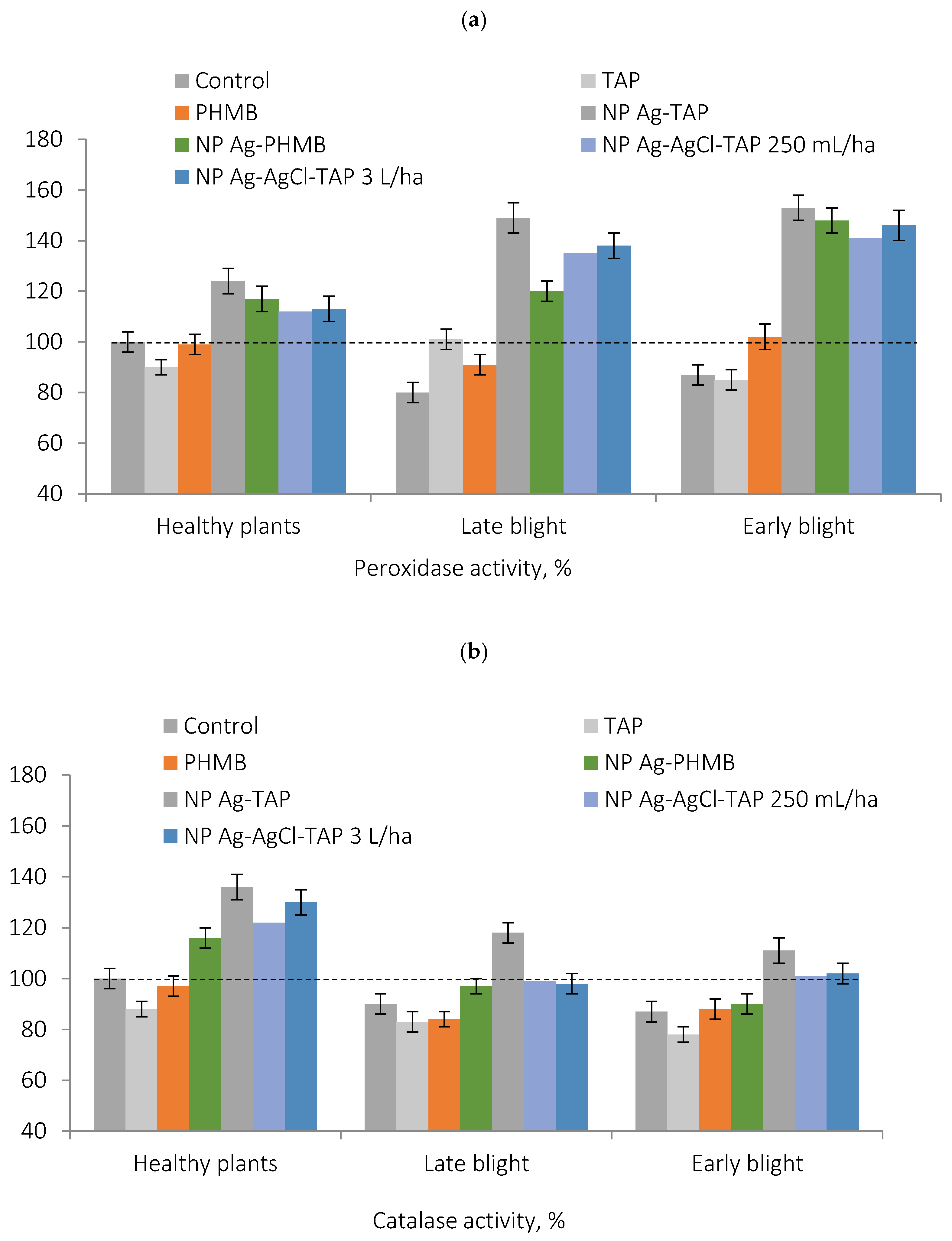

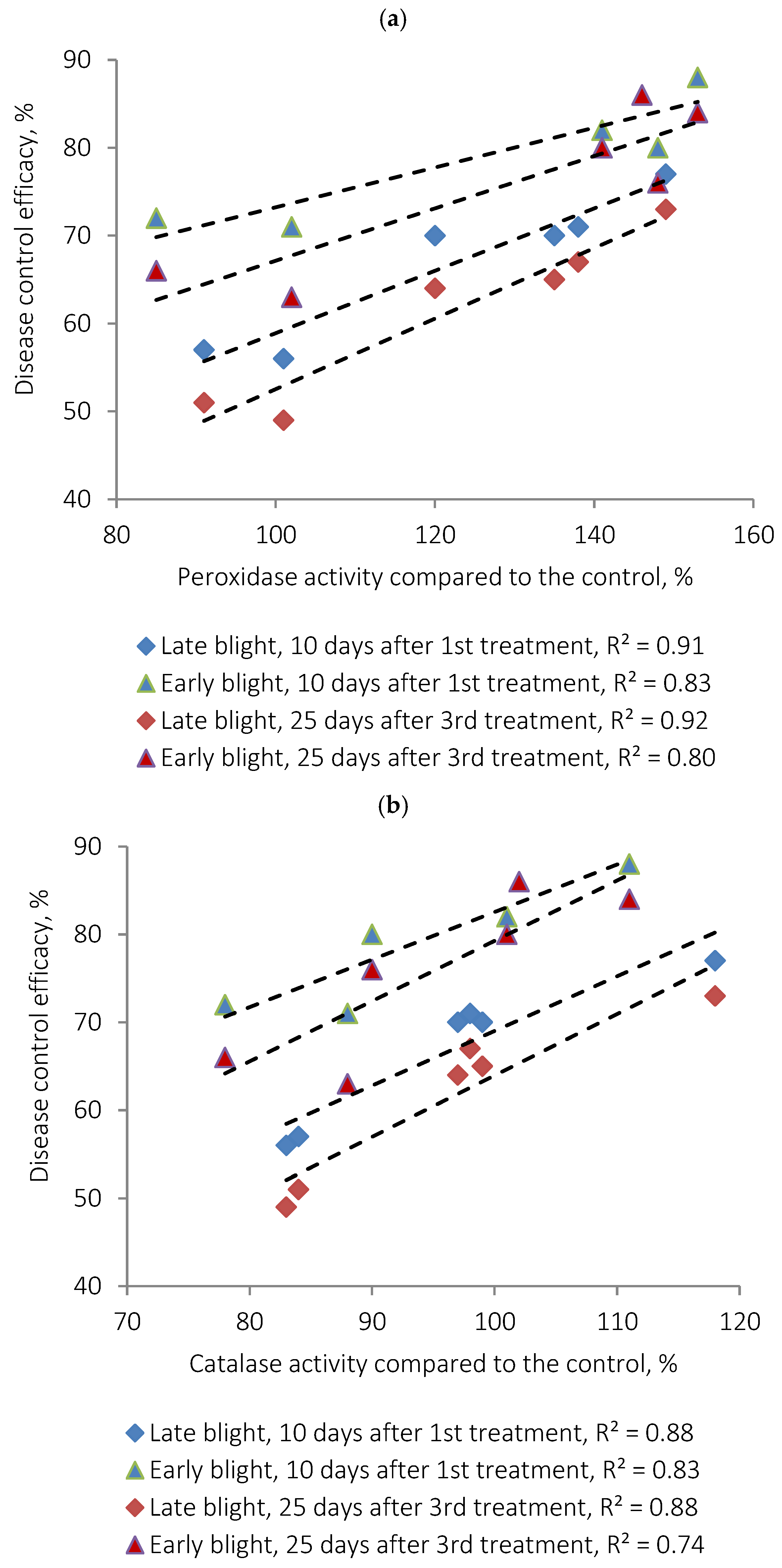

Measurements of POX and CAT activities in potato leaves revealed a significant increase in both enzymes following treatment with AgNPs (

Table 3 and

Table 4), indicating the onset of a controlled oxidative stress. This response correlates strongly with the observed suppression of

P. infestans and

A. solani: enzyme activity levels were positively correlated with disease control efficacy (

Figure 7 and

Figure 8), showing Pearson correlation coefficients of R

2 ≈ 0.8–0.9.

This differential modulation—increased POX activity coupled with partial suppression of CAT—is distinct from the coordinated upregulation of both enzymes previously observed in healthy potato plants of the early cultivar ‘Red Scarlet’ following foliar application of PHMB-stabilized AgNPs in the Pre-Kama region of Tatarstan [

35]. A similar pattern has been reported by observing wheat seeds treated with AgNPs under NaCl-induced salt stress [

36], though the underlying mechanism was not explained in that study.

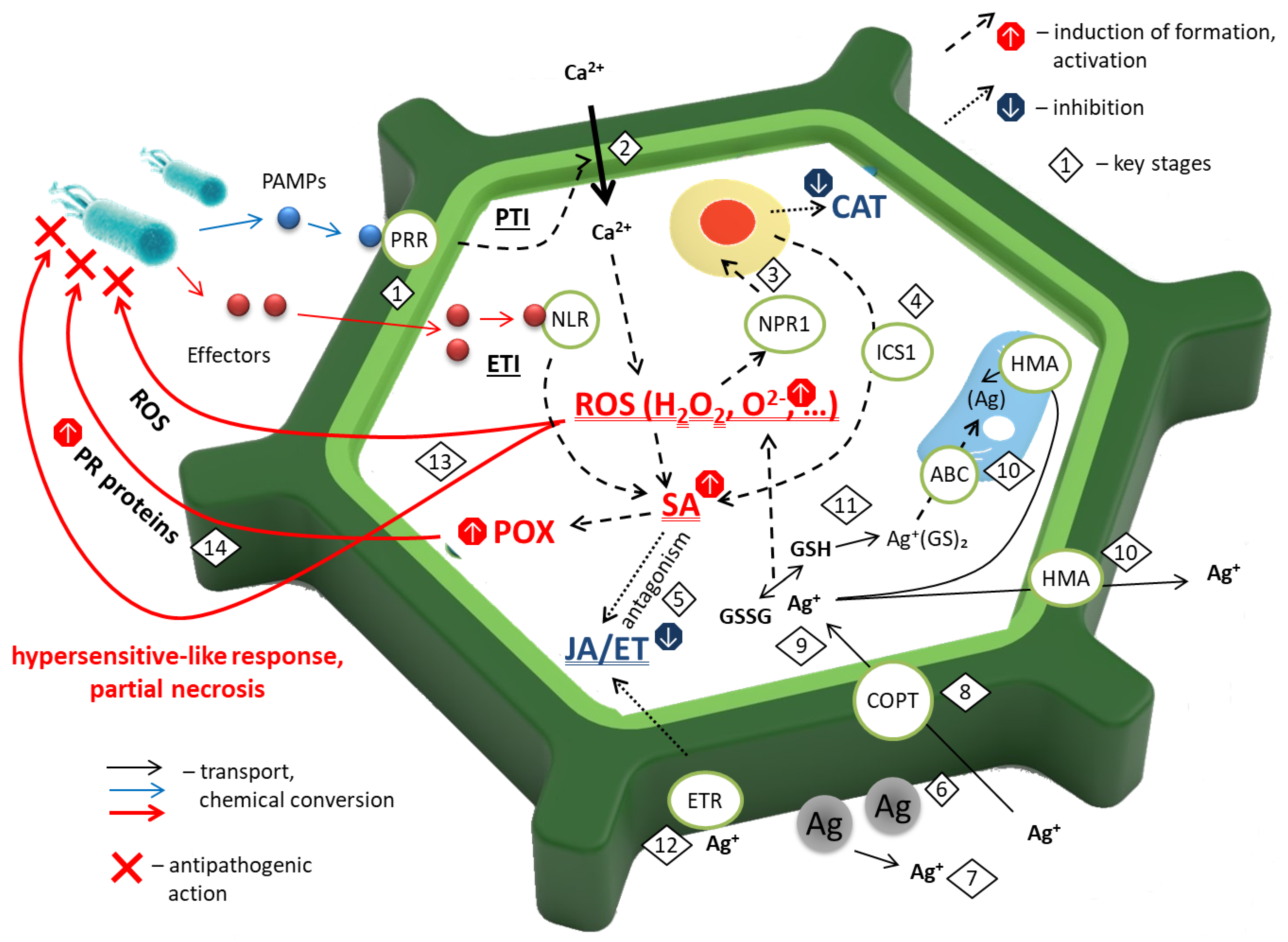

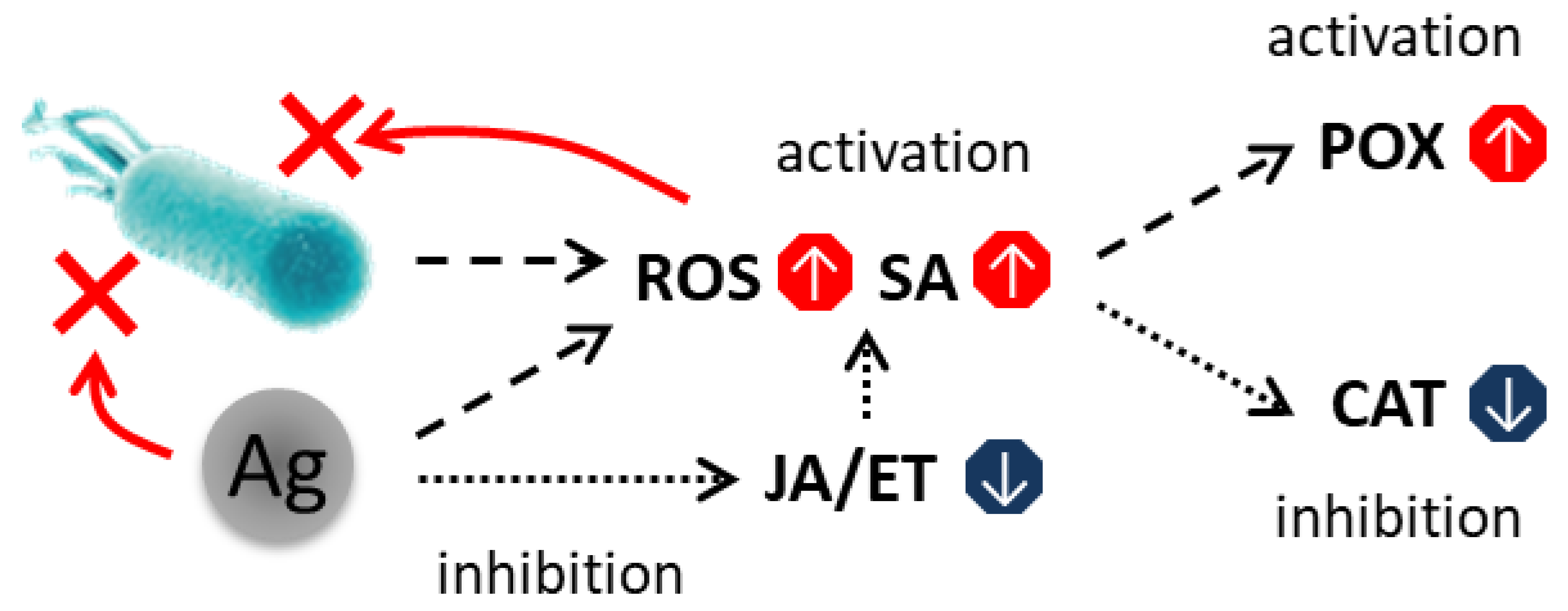

Based on our collective findings, we proposed a model of the action of AgNPs with respect to the plant antioxidant system under phytopathogenic stress (

Figure 9).

The stabilizing agents alone (PHMB and TAP) exerted considerably weaker effects on antioxidant enzyme activity, suggesting that the primary role in immune activation is played by AgNPs and/or Ag+ ions released through oxidation of Ag0 in planta under the influence of ROS and apoplastic oxygen.

The activity of catalase and peroxidase in plants treated with stabilizers alone was, in all cases, 15–40% lower than in plants treated with silver dispersions. The only exception refers to the weak influence of PHMB on catalase activity in the case of early blight-infected plants. This further supports the previously obtained evidence for the primary contribution of silver nanoparticles, rather than stabilizers, to preventing potato infections.

Krutyakov et al. [

48] previously showed that in the presence of H

2O

2, AgNPs stabilized by various surfactants and polymers, including the AgNPs used in the field studies, are readily oxidized by H

2O

2 with the release of Ag

+ ions; the kinetic characteristics of the process were also measured. This suggests that Ag

+ ions are formed from AgNPs in plant tissues under the influence of H

2O

2 and other ROS contained therein.

This upregulation of antioxidant enzymes—accompanied by increased H

2O

2 and lipid peroxidation products such as malondialdehyde (MDA)—has been previously reported in plants exposed to AgNPs [

36] and supports the proposed mechanism of POX and catalase induction via silver-triggered redox signaling.

To elucidate the mechanism by which AgNPs influence disease development, POX and CAT activities were measured separately in potato leaves exhibiting visible infection foci (

Table 3 and

Table 4).

In control plants, antioxidant enzyme activity was significantly reduced in infected leaves compared to healthy tissues. Given the extensive pathogen invasion observed during field trials, this decline likely reflects depletion of the plant’s defense resources, contributing to low disease resistance.

In contrast, following protective priming with AgNPs, leaf infection by A. solani and P. infestans led to a further increase in the POX activity—exceeding levels in healthy, non-inoculated plants. CAT activity decreased by 10–20% upon infection, both in control and AgNP-treated plants, consistent with its known downregulation under biotic stress. However, CAT activity remained significantly higher in AgNP-treated plants compared to the control, indicating a silver-mediated enhancement of enzymatic capacity despite infection.

Upon pathogen recognition, plants may activate a two-tiered immune system [

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42] (

Figure 9(1)): PAMP-triggered immunity (PTI) and effector-triggered immunity (ETI). PAMPs, such as bacterial flagellin or fungal chitin, are recognized (

Figure 9(1)) by membrane-localized receptor-like kinases (LRR-RLKs; e.g., FLS2, EFR, CERK1), triggering early defenses including cell wall reinforcement (callose, lignin), Ca

2+ uptake (

Figure 9(2)), ROS production via plasma membrane NADPH oxidases (RBOHD/RBOHF), activated by Ca

2+, phytoalexin synthesis, and the activation of pathogenesis-related (PR) genes (

Figure 9(3)).

Pathogens counteract PTI by delivering effector proteins into host cells. In pathogen-resistant plants, these effectors are detected directly or indirectly by intracellular nucleotide-binding leucine-rich repeat (NLR) receptors (

Figure 9(1)), activating ETI—a rapid, high-amplitude defense response often culminating in hypersensitive cell death at the site of infection [

43,

44,

45]. Signaling downstream of pathogen perception involves Ca

2+ influx (

Figure 9(2)), ROS bursts, MAPK cascades, and hormonal regulation via salicylic acid (SA) for biotroph defense, and jasmonic acid (JA)/ethylene (ET) for necrotroph resistance.

H

2O

2 and other ROS alter cellular redox status, promoting monomerization and nuclear translocation of the nonexpressor of pathogenesis-related genes (NPR1) [

46] (

Figure 9(3))—the central regulator of SAR—and stimulating SA biosynthesis (

Figure 9(4)) via isochorismate synthase 1 (ICS1).

SA, in turn, enhances hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

2) production, thereby establishing a positive feedback loop that amplifies oxidative stress [

47]. Furthermore, SA antagonizes JA-mediated signaling (

Figure 9(5)). NPR1, a central regulator of the SA pathway, translocates to the nucleus where it interacts with TGA transcription factors to activate pathogenesis-related (

PR) genes (

Figure 9(14)). Concurrently, NPR1-mediated activation suppresses the expression of JA-responsive genes, such as

LIPOXYGENASE 2 (

LOX2) and

VEGETATIVE STORAGE PROTEIN 2 (

VSP2). SA also inhibits JA biosynthesis by repressing the activity of lipoxygenase (LOX), the first enzyme in the JA biosynthetic pathway, and by stabilizing JASMONATE ZIM-DOMAIN (JAZ) repressor proteins [

45,

47].

Conversely, JA and ET suppress SA signaling. JAZ repressors physically interact with NPR1 and TGA transcription factors, thereby inhibiting SA-dependent gene expression. Ethylene can potentiate this suppression through the transcription factors EIN3 and EIL1 [

45,

47].

Following foliar application, AgNPs readily bind to cell wall components—particularly phenolic groups in lignin and carboxyl groups in pectins (

Figure 9(6)). In the apoplast, dissolved O

2 and existing ROS promote oxidative dissolution of Ag

0 to Ag

+ ions (

Figure 9(7)). Ag

+ enters cells (

Figure 9(8)) primarily via copper transporters (COPTs), due to its chemical similarity to Cu

+. Intracellular detoxification occurs through binding to thiol-containing compounds (

Figure 9(9)): GSH (forming Ag

+(GS)

2), phytochelatins (PCs, synthesized by PCS), and metallothioneins (MTs). These complexes are sequestered into the vacuole via ABC transporters (

Figure 9(10)), while excess Ag

+ may be extruded or compartmentalized by HMA-family transporters (

Figure 9(10)) [

13,

14,

26,

27,

28].

Two key mechanisms mediate AgNPs’ effect on the cellular metabolism:

Induction of oxidative stress via GSH (

Figure 9(9)) depletion (diverted to PC synthesis) and disruption of the ascorbate–glutathione cycle, leading to H

2O

2 accumulation (

Figure 9(11), also via disrupting energy metabolism [

49,

50];

Suppression of ET signaling, potentially through direct interaction with ET receptors (

Figure 9(12)).

Based on data reported by Azhar et al. [

51], plant cell membranes contain approximately 150 fmol of ethylene receptors per µg of membrane protein, which corresponds to roughly 150 fmol per mg of fresh leaf tissue. Given that the average fresh aboveground biomass of a potato plant at a stand density of 37,000 plants per hectare is approximately 400 g, each plant contains about 60 nmol of ethylene receptors. In field trials, potato plants were treated with nanoparticle dispersions at application rates of 0.1–9 g Ag per hectare, equivalent to 3–240 µg or 30–2200 nmol of silver per plant. Consequently, the amount of applied silver is sufficient to potentially inactivate a substantial fraction of native ethylene receptors.

As previously demonstrated, suppression of the ET signaling pathway results in inhibition of the JA-dependent signaling cascade, thereby promoting activation of the antagonistic SA pathway. A comparable shift toward SA-mediated signaling is also induced by the accumulation of hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

2) and other ROS. Consequently, upon intracellular uptake of silver, both mechanisms—ET pathway suppression and ROS accumulation—converge to potentiate SA-dependent immune responses. This, in turn, triggers a robust oxidative burst and elicits a defense reaction phenotypically resembling the hypersensitive response (HR) (

Figure 9(13)).

SA signaling leads to transcriptional repression of CAT genes (CAT1, CAT2, CAT3) via WRKY transcription factors and oxidative inactivation of CAT enzyme, reducing H2O2 scavenging. In contrast, POX activity increases via NPR1-dependent expression of class III POX genes (PRX). Thus, the observed enzyme dynamics reflect elicitor-driven activation of SA-mediated immunity, when H2O2 is used for defense instead of being removed.

In this context, the alterations in CAT and POX activities observed in our experiments are primarily attributable to the elicitor-like effects of AgNPs and Ag+ ions. Upon interaction with components of the plant cell wall, these agents stimulate the activity of both plasma membrane-localized NADPH oxidases (RBOHs) and cell wall-associated POXs, leading to a concomitant increase in apoplastic and symplastic ROS levels. This ROS burst acts as a secondary messenger, triggering the activation of transcription factors and subsequent upregulation of defense-related genes, including canonical resistance (R) genes.

Consequently, the plant prioritizes the synthesis of antimicrobial compounds and defense enzymes directly involved in pathogen containment—particularly ROS, POXs, and polyphenol oxidases—while catalase, which scavenges protective ROS, is produced in lesser quantities. This shift in the ROS-scavenging versus ROS-generating enzyme balance reflects a strategic reallocation of cellular resources toward defense.

Pre-treatment with AgNPs thus induces a state of defense priming: upon subsequent pathogen encounter, plants mount a rapid and robust non-specific immune response (

Figure 10). This primed state effectively restricts pathogen progression and prevents the exhaustion of the plant’s defensive capacity during prolonged infection.

Furthermore, considering recent evidence demonstrating the direct effects of silver ions and AgNPs on the catalytic activity of antioxidant enzymes [

32,

33,

34], an alternative mechanistic explanation for the observed enzymatic shifts can be proposed. Specifically, the increase in POX activity coupled with the decline in CAT activity may be caused not only by transcriptional regulation but also by the direct interaction of Ag

+ and AgNPs with enzyme molecules. Studies have shown that, within a specific concentration range, Ag

+ can enhance POX activity while simultaneously inhibiting CAT [

32,

33,

34].

Silver ions are released in plant tissues through the oxidative dissolution of AgNPs, a process accelerated by the increase in the concentration of oxidants such as molecular oxygen or ROS. Under conditions of mild oxidative stress—as typically observed in healthy, uninfected plants—the rate of AgNPs dissolution is limited, resulting in low Ag

+ concentrations that exert negligible direct effects on POX or CAT activity. However, during co-exposure to phytopathogens and AgNPs, oxidative stress is markedly amplified compared to the non-infected control. This leads to a substantial ROS burst, which in turn accelerates AgNPs dissolution and promotes localized accumulation of Ag

+ in infected tissues. Under these conditions, the direct modulatory effects of Ag

+ on enzyme conformation and function become significant: POX activity is potentiated, whereas CAT activity is suppressed—consistent with in vitro observations of Ag

+-enzyme interactions [

32,

33,

34].

Foliar application of AgNPs to potato plants thus can enhance disease resistance through a dual mechanism: (i) AgNP-induced ROS generation primes defense signaling, and (ii) the consequent rise in POX activity—potentiated both transcriptionally and post-translationally by Ag+—amplifies antimicrobial responses. Notably, despite the perturbation of redox homeostasis, treated plants maintain sufficient antioxidant capacity, as evidenced by their ability to upregulate both POX and CAT in response to pathogen invasion. The pivotal role of POXs loosely bound to the cell wall in conferring biotic stress tolerance in potato has been previously established.

Unlike CAT and SOD, whose primary function is ROS scavenging, POX-catalyzed reactions generate products with direct antimicrobial activity. For instance, oxidation of phenolic compounds by H

2O

2 in the presence of POX yields quinones and other derivatives exhibiting strong fungicidal properties [

6]. Additionally, these reactions produce high-molecular-weight, poorly soluble lignin-like polymers that reinforce cell walls, forming a physical barrier against pathogen spread and contributing to the formation of necrotic lesions—a hallmark of the hypersensitive response in infected leaves and stems [

52,

53].

Moreover, POXs serve as a major source of apoplastic ROS during pathogenesis. Therefore, AgNP-mediated enhancement of POX activity not only bolsters chemical defense but also sustains the oxidative burst required for effective pathogen containment.

Based on our findings and the established interplay between plant hormonal pathways, we propose the following mechanistic hypothesis to explain the observed peroxidase (POX) increase, catalase (CAT) decrease, and high disease control efficacy. Following foliar application, silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) are oxidized in the apoplast by tissue-derived hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and other ROS, releasing Ag+ ions (Stage 1). These ions, and potentially the nanoparticles themselves, then activate the plant’s ROS-mediated signaling network (Stage 2). A critical step involves the direct inhibition of membrane-localized ethylene receptors by Ag+ (Stage 3). This suppression of ethylene signaling consequently inhibits the antagonistic jasmonic acid (JA) pathway, leading to a shift in hormonal balance towards the salicylic acid (SA)-mediated signaling branch (Stage 4). The potentiated SA pathway triggers a robust oxidative burst, characterized by the strategic reprogramming of antioxidant enzymes: an upregulation of POX (to generate antimicrobial compounds and reinforce cell walls) and a concurrent downregulation of CAT (to preserve signaling H2O2). This primed, amplified oxidative response (Stage 5) directly and indirectly creates a hostile environment for the pathogens, leading to the significant suppression of P. infestans and A. solani infections observed in our field trials.

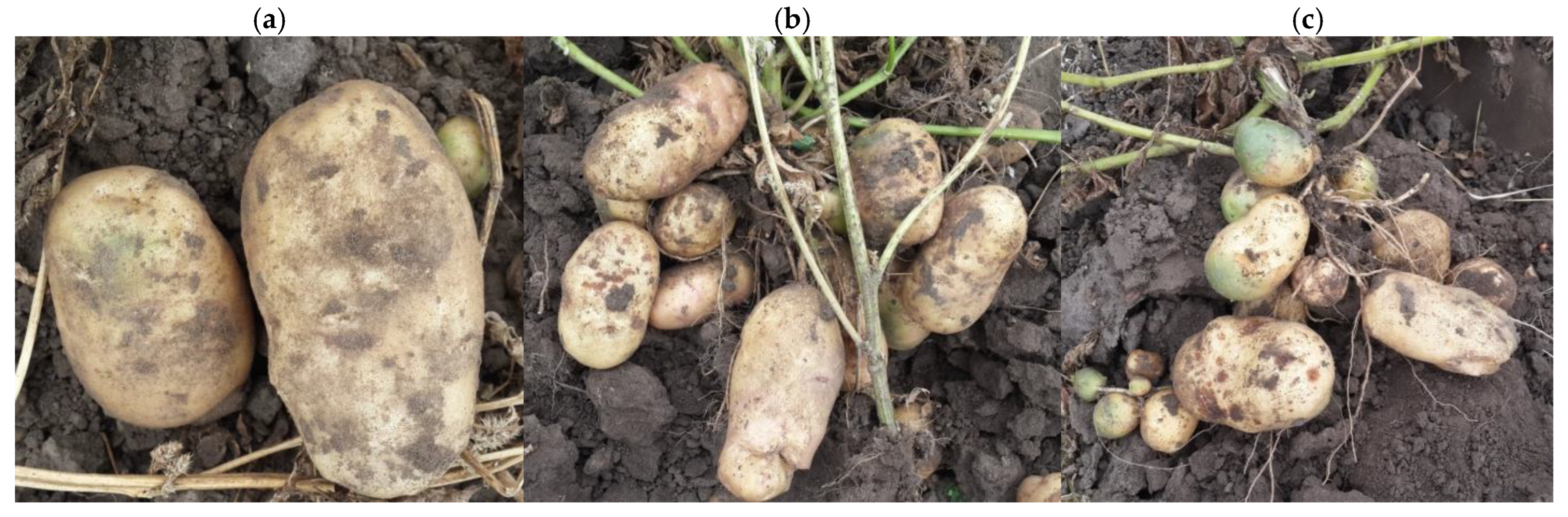

This mechanism is consistent with the outcome of our recent and previous [

54] field trials, which demonstrated reduced disease incidence and improved tuber yield in AgNP-treated plots compared to both the untreated control and the plots treated with stabilizers alone (

Table 5). Yield improvement was primarily due to the higher proportion of medium-sized tubers and fewer small tubers (

Table 5,

Figure 11).

In summary, when applied at optimized rates—where the elicitor-like, defense-priming effects of silver prevail over its phytotoxic potential—foliar sprays of AgNP dispersions effectively induce SAR and suppress disease progression. This translates into measurable agronomic benefits, including lower infection severity and increased potato yield.

Importantly, AgNP treatments did not significantly alter dry matter content, starch, vitamin C, or nitrate levels in tubers compared to the control (

Table 6), indicating no adverse impact on nutritional quality.

However, the prospective agricultural use of AgNPs as pesticides raises significant environmental concerns regarding their persistence, bioaccumulation potential, and effects on non-target soil ecosystems. The environmental impact of AgNPs is critically dependent on their synthesis route and subsequent transformations in the environment.

Silver nanoparticles do not persist indefinitely in their pristine metallic (Ag0) form in soil environments. They undergo a series of dynamic transformations that dictate their long-term fate and bioavailability.

The primary processes include aggregation (clumping of particles), oxidative dissolution (release of toxic Ag

+ ions), and sulfidation. Sulfidation, where Ag

0 reacts with sulfide to form Ag

2S, is particularly significant as it dramatically reduces the solubility and antimicrobial potency of AgNPs. This is the main pathway of inactivating AgNPs in soils [

13].

AgNPs can enter and move through both aquatic and terrestrial food chains, posing a risk of biomagnification. Terrestrial plants can absorb AgNPs through roots or foliar application. Once absorbed, nanoparticles can be translocated within the plant system. Evidence confirms the trophic transfer of various nanoparticles. For example, studies show that nanoparticles can be transferred from algae to water fleas (

Daphnia magna) and further to fish, accumulating in tissues like the liver, kidney, and muscle [

55]. This demonstrates a clear pathway for AgNPs to enter and ascend the food chain, with potential implications for higher organisms, including humans.

Modern research reveals a crucial and concerning difference between AgNPs stabilized by different agents regarding a long-term environmental risk. AgNPs stabilized by biodegradable polymers like those used in our field trials often exhibit less environmental risk than other AgNPs.