Twig and Leaf Morphological Traits and Photosynthetic Physiological Characteristics of Periploca sepium in Response to Different Light Environments in Taohe Riparian Forests

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Environmental Characteristics of Plant Community and Biological Characteristics in Different Light Environments

| Plot | Environmental Characteristics | Biological Characteristics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAR | SMC | T | RH | H | CW | |

| Under-canopy area | 662.15 ± 6.52 c | 23.96 ± 0.28 a | 24.16 ± 0.26 b | 82.98 ± 1.18 a | 128.60 ± 1.71 a | 1.27 ± 0.013 a |

| Gap area | 856.55 ± 11.44 b | 18.15 ± 0.13 b | 24.98 ± 0.38 ab | 69.04 ± 0.69 b | 118.00 ± 1.75 b | 0.79 ± 0.012 a |

| Full-sun area | 1224.63 ± 10.87 a | 14.34 ± 0.18 c | 25.47 ± 0.37 a | 50.54 ± 0.61 c | 98.56 ± 1.18 c | 0.53 ± 0.078 c |

2.2. Twig and Leaf Traits of Periploca sepium in Response to Varying Light Environments

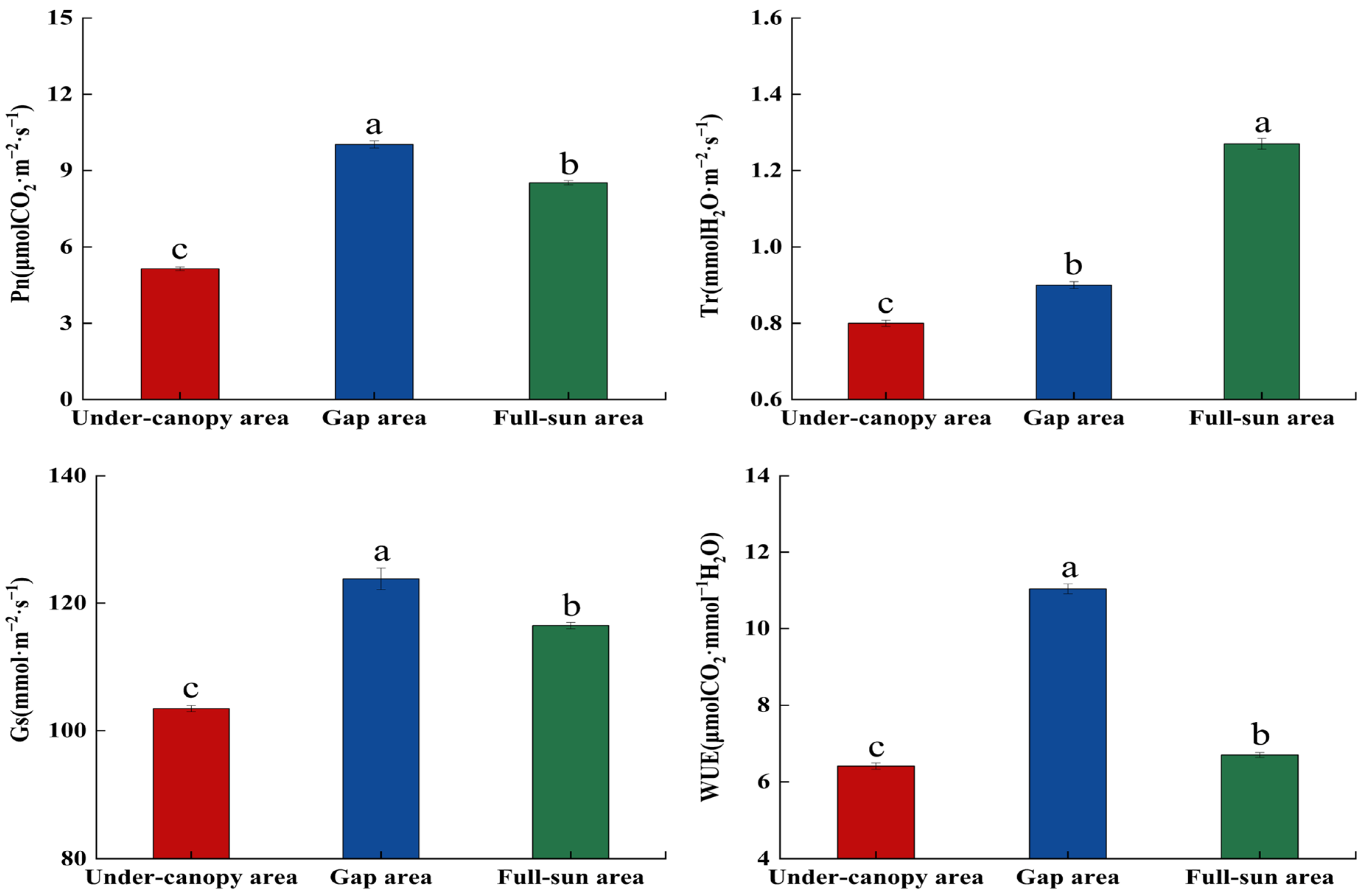

2.3. Photosynthetic Physiological Traits of Periploca sepium in Response to Varying Light Environments

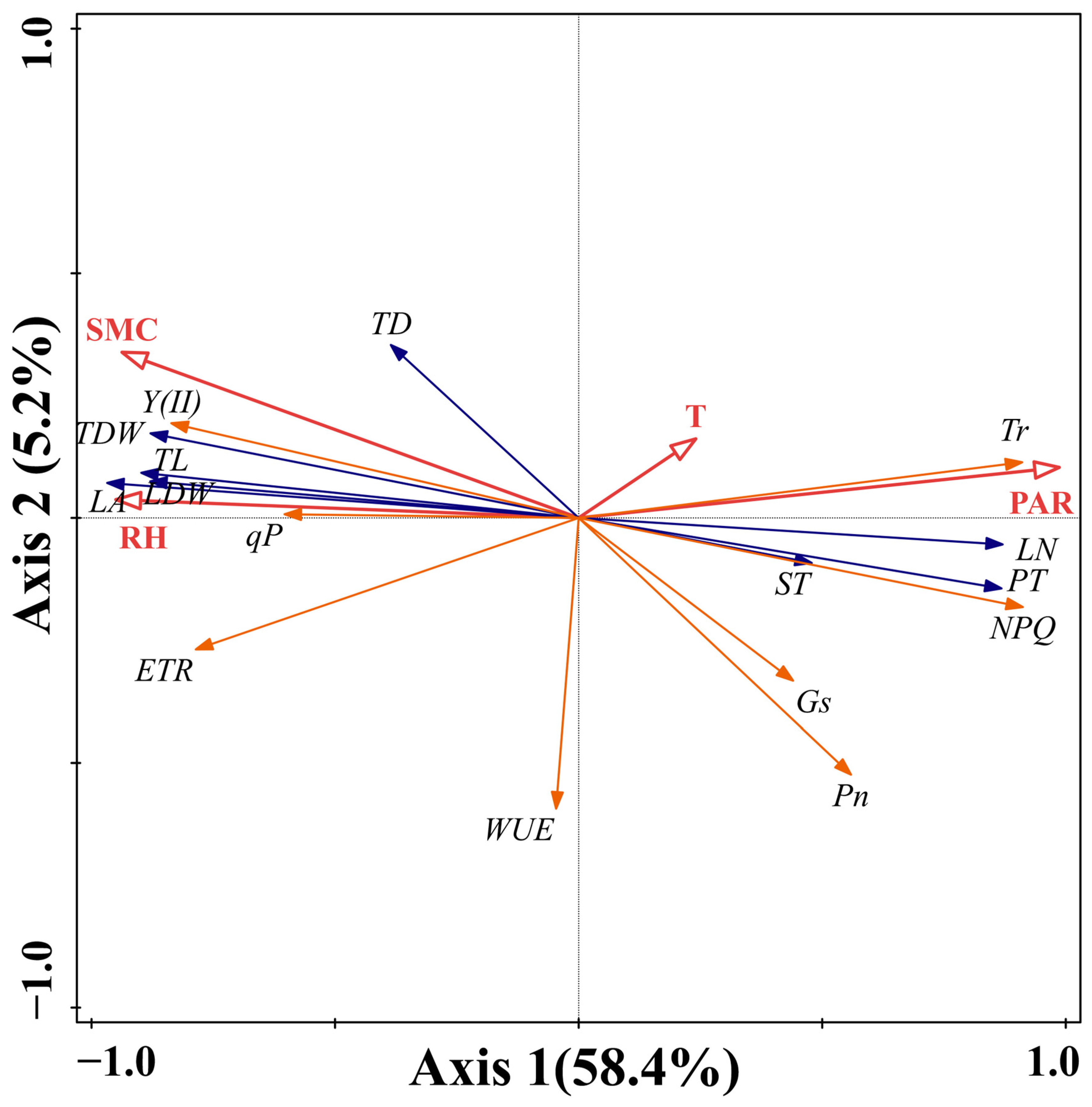

2.4. Effects of Environmental Factors on Functional Traits of Periploca sepium

2.5. Relationships Between Twig and Leaf Morphological Traits and Photosynthetic Characteristics of Periploca sepium

3. Discussion

3.1. Responses of Twig and Leaf Morphologies and Photosynthetic Characteristics of Periploca sepium to the Light Environment in the Under-Canopy Area

3.2. Responses of Twig and Leaf Morphologies and Photosynthetic Characteristics of Periploca sepium to the Light Environment in the Full-Sun Area

3.3. Responses of Twig and Leaf Morphologies and Photosynthetic Characteristics of Periploca sepium to the Light Environment in the Gap Area

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Site

4.2. Field Experiment Methods and Designs

4.2.1. Determination of Gas Exchange Parameters

4.2.2. Determination of Chlorophyll Fluorescence Parameters

4.2.3. Determination of Twig and Leaf Morphological Characteristics

4.2.4. Measurement of Environmental Factors

4.3. Data Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Martinez, K.A.; Fridley, J.D. Acclimation of Leaf Traits in Seasonal Light Environments: Are Non-Native Species More Plastic? J. Ecol. 2018, 106, 2019–2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.Q.; Jin, G.Z.; Liu, Z.L. Variation and Relationships between Twig and Leaf Traits of Species across Successional Status in Temperate Forests. Scand. J. For. Res. 2019, 34, 647–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granata, M.U.; Bracco, F.; Nola, P.; Catoni, R. Photosynthetic Characteristic and Leaf Traits Variations along a Natural Light Gradient in Acer campestre and Crataegus monogyna. Flora 2020, 268, 151626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helbach, J.; Frey, J.; Messier, C.; Mörsdorf, M.; Scherer-Lorenzen, M. Light Heterogeneity Affects Understory Plant Species Richness in Temperate Forests Supporting the Heterogeneity-Diversity Hypothesis. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 12, e8534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.Y.; Gao, Y.C.; Huang, X.N.; Li, S.G.; Zhan, A.B. Local Environment-Driven Adaptive Evolution in a Marine Invasive Ascidian (Molgula manhattensis). Ecol. Evol. 2021, 11, 4252–4266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abakumova, M.; Zobel, K.; Lepik, A.; Semchenko, M. Plasticity in Plant Functional Traits Is Shaped by Variability in Neighbourhood Species Composition. New Phytol. 2016, 211, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, C.C.; Sack, L.; Xu, L.i.; Li, M.X.; Zhang, J.H.; He, N.P. Leaf Trait Network Architecture Shifts with Species-Richness and Climate across Forests at Continental Scale. Ecol. Lett. 2022, 25, 1442–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, M.A.; Rosa, S.; Sicard, A. Mechanisms Underlying the Environmentally Induced Plasticity of Leaf Morphology. Front. Genet. 2018, 9, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermlin, H.K.; Lepik, M.; Zobel, K. The Importance of Shoot Morphological Plasticity on Plant Coexistence: A Pot Experiment. Plant Biol. 2022, 24, 791–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, E.Q.; Weng, E.S.; Yan, E.R.; Xia, J.Y. Robust Leaf Trait Relationships across Species under Global Environmental Changes. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.S.; Wang, C.; Zhou, C.N. The Variation of Functional Traits in Leaves and Current-Year Twigs of Quercus aquifolioides along an Altitudinal Gradient in Southeastern Tibet. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 10, 855547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosas, T.; Mencuccini, M.; Barba, J.; Cochard, H.; Saura-mas, S.; Martinez-Vilalta, J. Adjustments and Coordination of Hydraulic, Leaf and Stem Traits along a Water Availability Gradient. New Phytol. 2019, 223, 632–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouat, C.; Mckey, D. Leaf-Stem Allometry, Hollow Stems, and the Evolution of Caulinary Domatia in Myrmecophytes. New Phytol. 2001, 151, 391–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Ma, M.; Tang, Y.R.; Zhao, T.T.; Zhao, C.Z.; Li, B. Correlation Analysis of Twig and Leaf Characteristics and Leaf Thermal Dissipation of Hippophae rhamnoides in the Riparian Zone of the Taohe River in Gansu Province, China. Plants 2025, 14, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FunK, J.L.; Jones, C.G.; Lerdau, M.T. Leaf- and Shoot-Level Plasticity in Response to Different Nutrient and Water Availabilities. Tree Physiol. 2007, 27, 1731–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Normand, F.; Bissery, C.; Damour, G.; Lauri, P.É. Hydraulic and Mechanical Stem Properties Affect Leaf–Stem Allometry in Mango Cultivars. New Phytol. 2008, 178, 590–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.C.; Jin, D.M.; Shi, P. The Leaf Size-Twig Size Spectrum of Temperate Woody Species along an Altitudinal Gradient: An Invariant Allometric Scaling Relationship. Ann. Bot. 2006, 97, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zeng, F.P.; Zeng, Z.X.; Du, H.; Su, L.; Zhang, L.J.; Lu, M.Z.; Zhang, H. Impact of Selected Environmental Factors on Variation in Leaf and Branch Traits on Endangered Karst Woody Plants of Southwest China. Forests 2022, 13, 1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusk, C.H.; Grierson, E.R.P.; Laughlin, D.C. Large Leaves in Warm, Moist Environments Confer an Advantage in Seedling Light Interception Efficiency. New Phytol. 2019, 223, 1319–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamori, M. Photosynthetic Response to Fluctuating Environments and Photoprotective Strategies under Abiotic Stress. J. Plant Res. 2016, 129, 379–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brestic, M.; Allakhverdiev, S.I. Photosynthesis under Biotic and Abiotic Environmental Stress. Cells 2022, 11, 3953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meravi, N.; PrajapatiI, S.K. Seasonal Variation in Chlorophyll a Fluorescence of Butea monosperma. Biol. Rhythm Res. 2020, 51, 879–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Z.Y.; Lu, Q.F.; Huo, H.Y.; Zhang, H.L. Estimation of Chlorophyll Fluorescence at Different Scales: A Review. Sensors 2019, 19, 3000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.M.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.L.; Wan, J.M. Leaf Chloroplast Ultrastructure and Photosynthetic Properties of a Chlorophyll-Deficient Mutant of Rice. Photosynthetica 2014, 52, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swoczyna, T.; Kalaji, H.M.; Bussotti, F.; Mojski, J.; Pollastrini, M. Environmental Stress-What Can We Learn from Chlorophyll a Fluorescence Analysis in Woody Plants? A Review. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1048582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.N.; Chen, Y.P.; Zhou, H.H.; Hao, X.M.; Zhu, C.G.; Fu, A.H.; Yang, Y.H.; Li, W.H. Research Advances in Plant Physiology and Ecology of Desert Riparian Forests under Drought Stress. Forests 2022, 13, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohberger, B.; Wagner, S.; Wohlmuther, J.; Kaltenegger, H.; Stuendl, N.; Leithner, A.; Rinner, B.; Kunert, O.; Bauer, R.; Kretschmer, N. Periplocin, the most anti-proliferative constituent of Periploca sepium, specifically kills liposarcoma cells by death receptor mediated apoptosis. Phytomedicine 2018, 51, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.M.; Liu, Y.T.; Huang, Y.T.; Yang, X.Q.; Zhu, F.H.; Tang, W.; Zhao, W.M.; He, S.J.; Zuo, J.P. Anti-nociceptive, anti-inflammatory and anti-arthritic activities of pregnane glycosides from the root bark of Periploca sepium Bunge. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 265, 113345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bamba, T.; Sando, T.; Miyabashira, A.; Gyokusen, K.; Nakazawa, Y.; Su, Y.Q.; Fukusaki, E.; Kobayashi, A. Periploca sepium Bunge as a model plant for rubber biosynthesis study. Z. Naturforsch. C 2007, 62, 579–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Zhang, J.W.; Ma, S.C.; Gao, L.; Chen, C.C.; Ji, Z.Q.; Hu, Z.N.; Shi, B.J.; Wu, W.J. Identification and mechanism of insecticidal periplocosides from the root bark of Periploca sepium Bunge. Pest Manag. Sci. 2021, 77, 1925–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, X.X.; Yang, X.; Wu, X.M.; Wang, Z.Y.; Zhao, Y.Y.; Lin, C.M.; Yu, S.; Wang, G.H.; Zhou, H.J. Effect of the odour compound from Periploca sepium Bunge on the physiological and biochemical indices, photosynthesis and ultrastructure of the leaves of Humulus scandens (Lour.) Merr. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 238, 113556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Y.Y.; Liang, Z.S. Drought tolerance of Periploca sepium during seed germination: Antioxidant defense and compatible solutes accumulation. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2013, 35, 959–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Y.Y.; Liang, Z.S.; Zhang, Y. Seed germination responses of Periploca sepium Bunge, a dominant shrub in the Loess hilly regions of China. J. Arid Environ. 2011, 75, 504–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.K.; Li, T.; Xia, J.B.; Tian, J.Y.; Lu, Z.H.; Wang, R.T. Influence of salt stresses on ecophysiological parameters of Periploca sepium Bunge. Plant Soil Environ. 2011, 57, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Y.Y.; Liang, Z.S.; Zhao, R.K.; Zhang, J.; Wang, X.J. Organ-dependent responses of Periploca sepium to repeated dehydration and rehydration. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2011, 77, 446–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xia, J.B.; Cao, X.B. Physiological and ecological characteristics of Periploca sepium Bunge under drought stress on shell sand in the Yellow River Delta of China. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 9567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Sun, J.; Yang, H.; Liu, J.; Xia, J.; Shao, P. Effects of shell sand burial on seedling emergence, growth and stoichiometry of Periploca sepium Bunge. BMC Plant Biol. 2020, 20, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Guo, Q.; Luo, S.; Pan, J.; Yao, S.; Gao, C.; Guo, Y.; Wang, G. Light Regimes Regulate Leaf and Twig Traits of Camellia oleifera (Abel) in Pinus massoniana Plantation Understory. Forests 2022, 13, 918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.Y.; Luo, G.Y.; Jin, Z.X.; Li, J.M.; Li, Y.L. Physiological and Structural Changes in Leaves of Platycrater arguta Seedlings Exposed to Increasing Light Intensities. Plants 2024, 13, 1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, W.H.; Shi, P.J.; Wang, J.F.; Mu, Y.Y.; Cao, J.J.; Niklas, K.J. The “Leafing Intensity Premium” Hypothesis and the Scaling Relationships of the Functional Traits of Bamboo Species. Plants 2024, 13, 2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Chen, X.P.; Wang, M.T.; Li, J.L.; Zhong, Q.L.; Chen, D.L. Application of Leaf Size and Leafing Intensity Scaling across Subtropical Trees. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 10, 13395–13402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, P.; Tommaso, A.; Olson, M.E. Leaf Length Predicts Twig Xylem Vessel Diameter across Angiosperms. Plant Cell Environ. 2025, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, N.; Okada, N. Coordination of Leaf and Stem Traits in 25 Species of Fagaceae from Three Biomes of East Asia. Botany 2019, 97, 391–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scoffoni, C.; Rawls, M.; Mckown, A.; Cochard, H.; Sack, L. Decline of Leaf Hydraulic Conductance with Dehydration: Relationship to Leaf Size and Venation Architecture. Plant Physiol. 2011, 156, 832–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.Y.; Zhong, L.F.; Tian, Q.Y.; Zhao, W.Z. Leaf Water Potential-Dependent Leaflet Closure Contributes to Legume Leaves Cool Down and Drought Avoidance under Diurnal Drought Stress. Tree Physiol. 2022, 42, 2239–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leigh, A.; Sevanto, S.; Close, J.D.; Nicotra, A.B. The Influence of Leaf Size and Shape on Leaf Thermal Dynamics: Does Theory Hold up under Natural Conditions? Plant Cell Environ. 2017, 40, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larbi, A.; Vázquez, S.; El-Jendoubi, H.; Msallem, M.; Abadía, J.; Abadía, A.; Morales, F. Canopy Light Heterogeneity Drives Leaf Anatomical, Eco-Physiological, and Photosynthetic Changes in Olive Trees Grown in a High-Density Plantation. Photosynth. Res. 2015, 123, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.G.; Bauerle, W.L.; Mudder, B.T. Effects of Light Acclimation on the Photosynthesis, Growth, and Biomass Allocation in American Chestnut (Castanea dentata) Seedlings. For. Ecol. Manag. 2006, 226, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Li, Q.; Zhao, C.Z.; Kang, M.P. Morphological Traits and Biomass Allocation of Leymus secalinus along Habitat Gradient in a Floodplain Wetland of the Heihe River, China. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stotz, G.C.; Salgado-Luarte, C.; Escobedo, V.M.; Valladares, F.; Gianoli, E. Global Trends in Phenotypic Plasticity of Plants. Ecol. Lett. 2021, 24, 2267–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsushita, M.; Tsubomura, M.; Kimura, M.; Takahashi, Y.; Ogawa, K.; Ohira, M.; Tamura, A. The Effects of Light Intensity on the Shoot Growth, Survival, and Reproductive Traits of Chamaecyparis obtusa Clones. New For. 2025, 56, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.H.; Fang, J.Y.; Ma, W.H.; Guo, D.L.; Mohammat, A. Large-Scale Pattern of Biomass Partitioning across China’s Grasslands. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2010, 19, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wen, J.; Zhao, C.Z.; Zhao, L.C.; Ke, D. The Relationship between the Main Leaf Traits and Photosynthetic Physiological Characteristics of Phragmites australis under Different Habitats of a Salt Marsh in Qinwangchuan, China. AoB Plants 2022, 14, plac054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.Y.; Zhao, C.Z.; Li, G.Y.; Chen, Z.N.; Wang, S.H.; Huang, C.L.; Zhang, P.X. Shrub Leaf Area and Leaf Vein Trait Trade-Off in Response to the Light Environment in a Vegetation Transitional Zone. Funct. Plant Biol. 2024, 51, FP24011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Zhao, X.W.; Wang, Y.; Ma, X.Y.; Li, H.L.; Zhao, C.Z. Effects of Selenium on Leaf Traits and Photosynthetic Characteristics of Eggplant. Funct. Plant Biol. 2025, 52, FP24292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Z.; Zhang, Y.R.; Dong, F.F.; Chen, L.J.; Li, Z.Y. Linkage between Leaf Anatomical Structure and Key Leaf Economic Traits across Co-Existing Species in Temperate Forests. Plant Soil 2025, 509, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ma, M.; Zhao, C.; Li, Q.; Hou, G.; Chen, J. Twig and Leaf Morphological Traits and Photosynthetic Physiological Characteristics of Periploca sepium in Response to Different Light Environments in Taohe Riparian Forests. Plants 2026, 15, 179. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020179

Ma M, Zhao C, Li Q, Hou G, Chen J. Twig and Leaf Morphological Traits and Photosynthetic Physiological Characteristics of Periploca sepium in Response to Different Light Environments in Taohe Riparian Forests. Plants. 2026; 15(2):179. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020179

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Min, Chengzhang Zhao, Qun Li, Gang Hou, and Junxian Chen. 2026. "Twig and Leaf Morphological Traits and Photosynthetic Physiological Characteristics of Periploca sepium in Response to Different Light Environments in Taohe Riparian Forests" Plants 15, no. 2: 179. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020179

APA StyleMa, M., Zhao, C., Li, Q., Hou, G., & Chen, J. (2026). Twig and Leaf Morphological Traits and Photosynthetic Physiological Characteristics of Periploca sepium in Response to Different Light Environments in Taohe Riparian Forests. Plants, 15(2), 179. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020179