In Vitro Antioxidant, Photoprotective, and Volatile Compound Profile of Supercritical CO2 Extracts from Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale L.) Flowers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

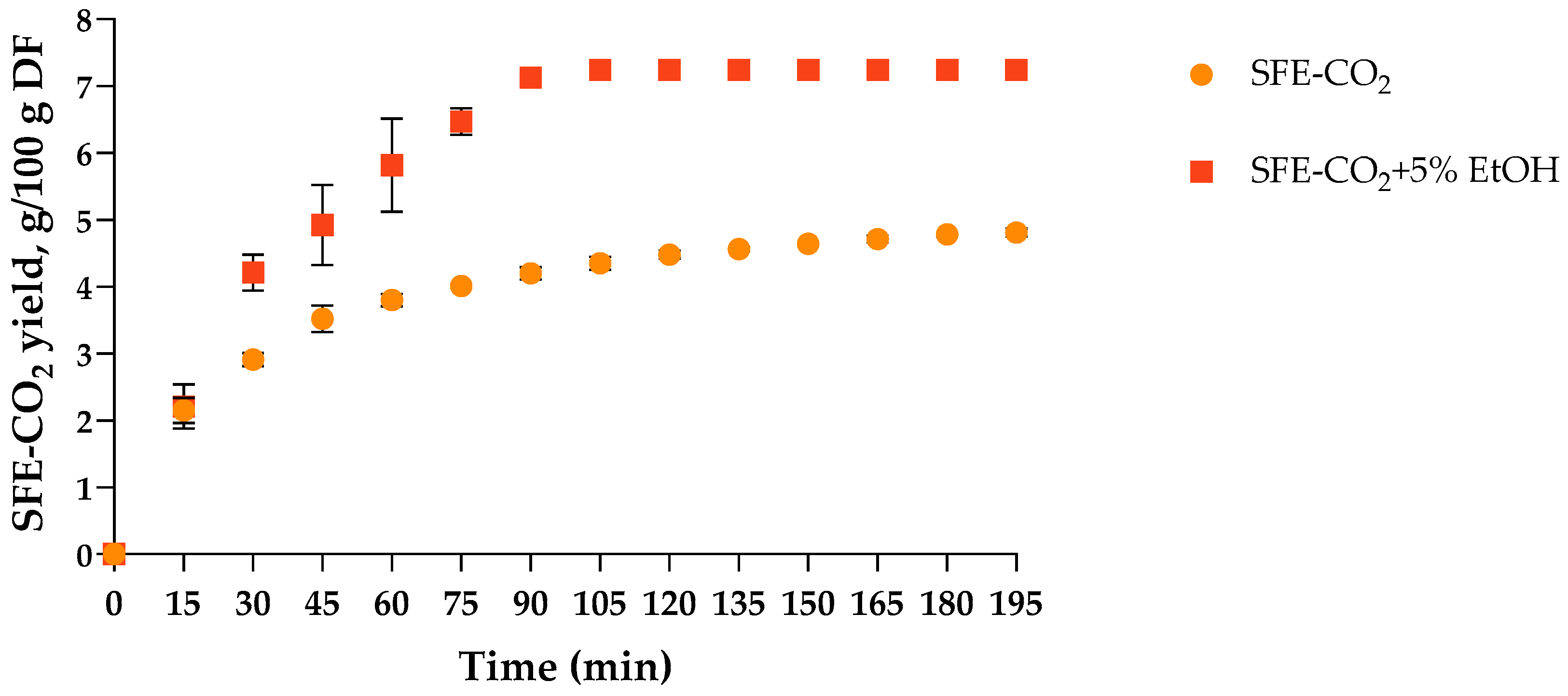

2.1. Preparation of SFE-CO2 Extracts from T. officinale Flowers

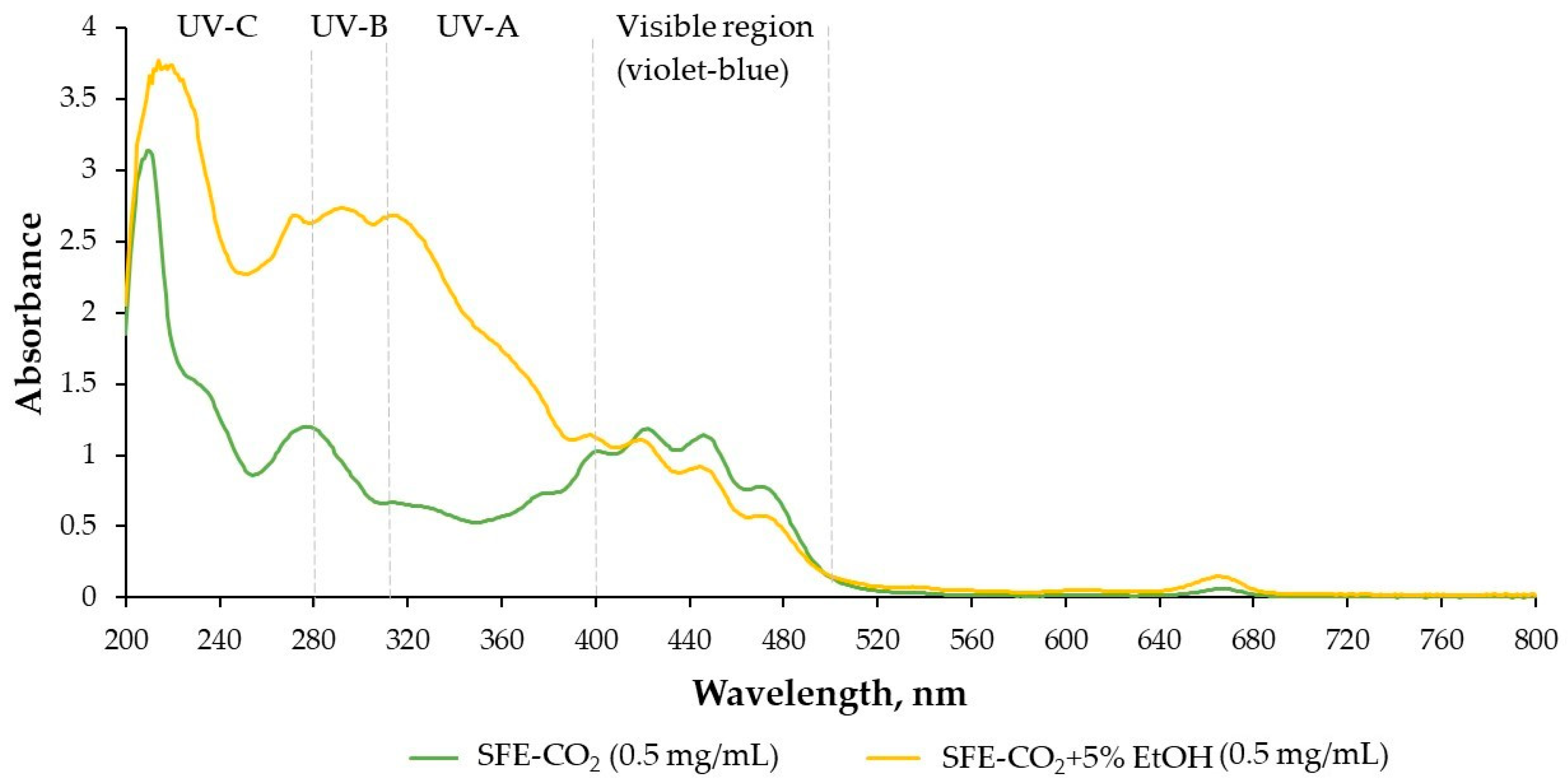

2.2. In Vitro Antioxidant and Photoprotective Properties of T. officinale SFE-CO2 Extracts

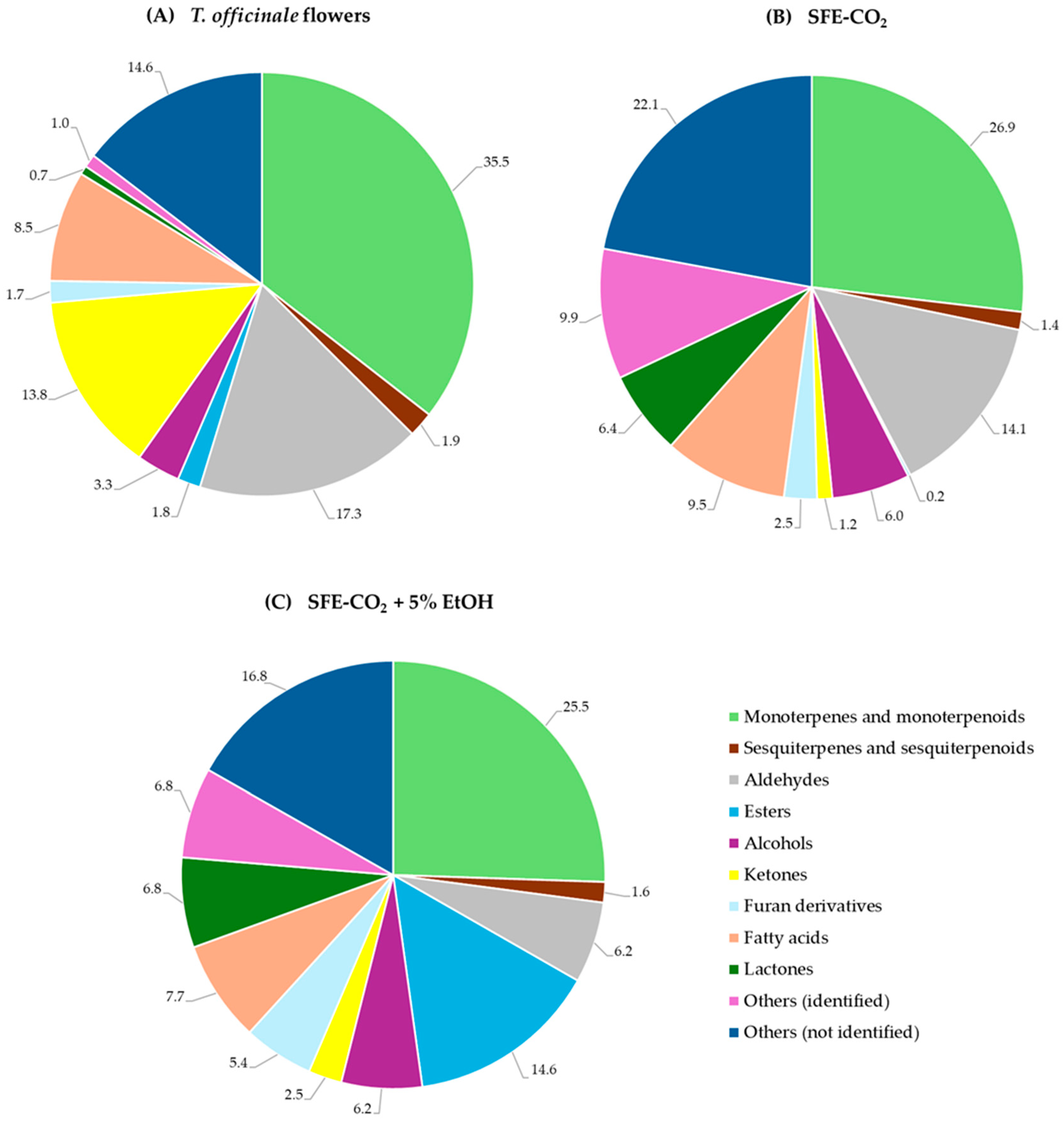

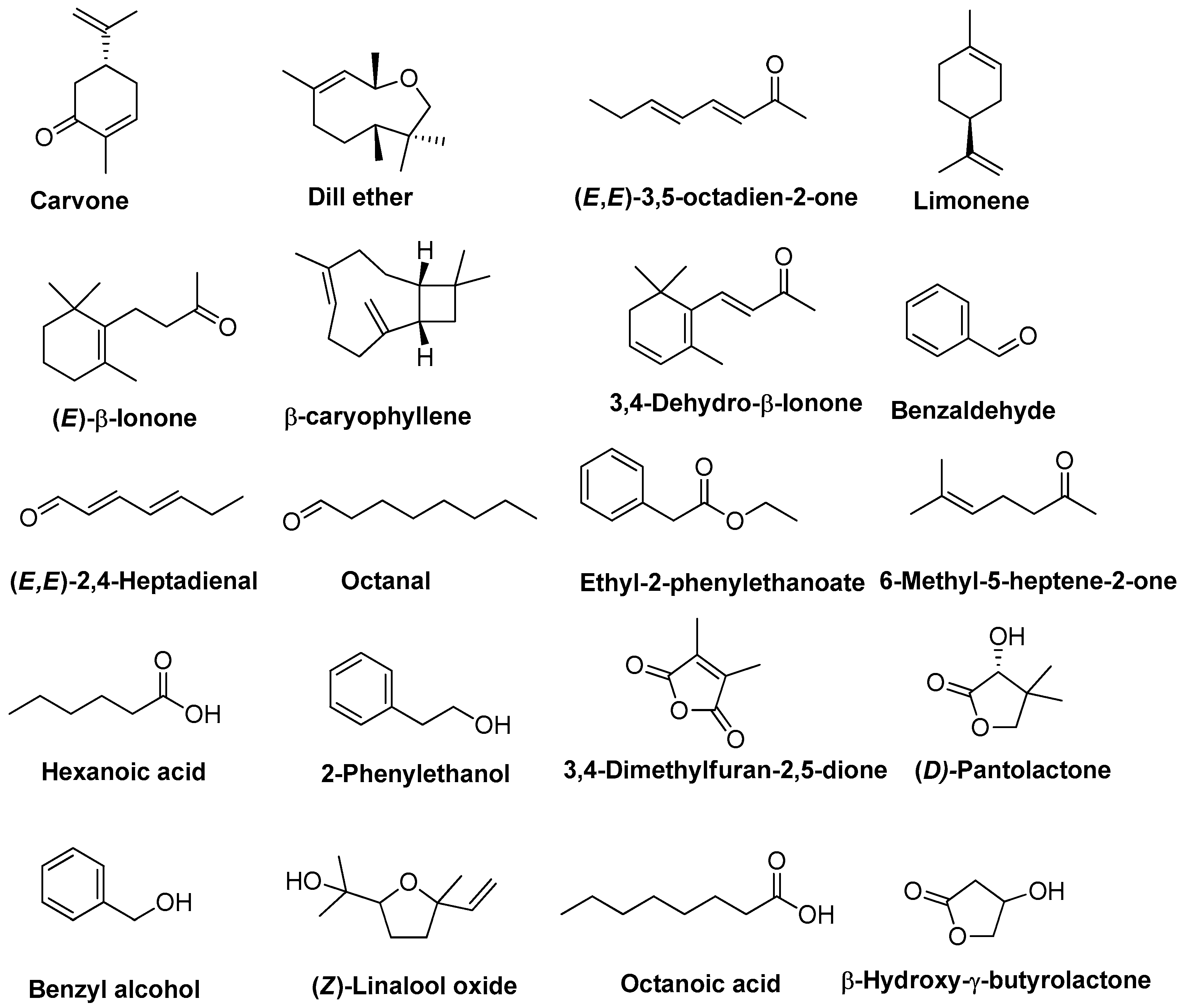

2.3. Volatile Compound Profile of T. officinale Flowers and SFE-CO2 Extracts

| Compound | LRIexp | LRIlit | Exact Mass | Formula | % of the Total GC Peak Area | Odour Type: Description A | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flowers | SFE-CO2 | SFE-CO2 + 5% EtOH | ||||||

| Monoterpenes and monoterpenoids | ||||||||

| α-Phellandrene | 1006 | 1007 [52] | 136.1252 | C10H16 | 0.84 ± 0.03 | -ND | -ND | Terpenic: citrus, herbal, terpenic, green, woody, black pepper |

| p-Cymene | 1027 | 1020 [53] | 134.1096 | C10H14 | 0.43 ± 0.01 | -ND | -ND | Terpenic: citrus, sweet |

| Limonene | 1030 | 1024 [53] | 136.1252 | C10H16 | 3.78 ± 0.23 b | -ND | 0.33 ± 0.10 a | Terpenic: terpenic, pine, peppery |

| Linalool | 1102 | 1095 [53] | 154.1358 | C10H18O | 0.35 ± 0.02 | -ND | -ND | Floral: citrus, orange, floral, waxy, rose |

| (Z)-Linalool oxide (pyranoid) | 1175 | 1170 [53] | 170.1307 | C10H18O2 | 0.44 ±0.19 a | 3.97 ± 0.00 c | 2.36 ± 0.00 b | Citrus: citrus, green |

| Dill ether | 1193 | 1184 [53] | 152.1201 | C10H16O | 5.83 ± 0.02 c | 4.26 ± 0.00 a | 4.54 ± 0.00 b | Herbal: herbal, dill |

| (E)-Dihydrocarvone | 1203 | 1200 [53] | 152.1201 | C10H16O | 2.28 ±0.05 b | 1.47 ± 0.13 a | 1.50 ± 0.05 a | Herbal: warm, herbal |

| Estragole | 1205 | 1195 [53] | 148.0888 | C10H12O | 2.19 ± 0.07 b | 1.47 ± 0.13 a | 1.50 ± 0.05 a | Anisic: sweet, phenolic, anise, spicy, green, herbal, minty |

| Safranal | 1207 | 1196 [53] | 150.1045 | C10H14O | 1.51 ± 0.19 b | -ND | 0.24 ± 0.05 a | Herbal: fresh, herbal, phenolic, metallic, rosemary, tobacco, spicy |

| β-Cyclocitral | 1228 | 1217 [53] | 152.1201 | C10H16O | 0.54 ± 0.07 | -ND | -ND | Tropical: tropical, saffron, herbal, rose, sweet, tobacco, green, fruity |

| Carvone | 1253 | 1242 [53] | 150.1045 | C10H14O | 16.46 ± 0.10 b | 14.10 ±0.17 a | 14.03 ± 0.06 a | Herbal: spicy, green, sweet, spearmint, mint, carraway dill |

| Thymol | 1296 | 1289 [53] | 150.1045 | C10H14O | 0.16 ± 0.04 a | 0.91 ± 0.01 c | 0.56 ± 0.07 b | Herbal: herbal, thyme, phenolic, medicinal, camphoreous |

| (E)-Geranyl acetone | 1457 | 1453 [53] | 194.1671 | C13H22O | 0.73 ± 0.01 b | 0.69 ± 0.04 b | 0.46 ± 0.06 a | Floral: fresh, green, fruity, waxy, rose, woody, magnolia, tropical |

| Sesquiterpenes and sesquiterpenoids | ||||||||

| β-Caryophyllene | 1429 | 1420 [52] | 204.1878 | C15H24 | 0.62 ± 0.13 a | 0.64 ± 0.23 a | 0.44 ± 0.07 a | Woody: woody, spicy |

| (E)-β-Farnesene | 1460 | 1459 [52] | 204.1878 | C15H24 | 0.33 ± 0.00 b | 0.04 ± 0.00 a | -ND | Woody: woody, citrus, herbal, sweet |

| 3,4-Dehydro-β-ionone | 1492 | 1485 [54] | 190.1358 | C13H18O | 0.12 ± 0.00 a | 0.33 ± 0.00 b | 0.57 ± 0.00 c | Floral: sweet, floral, fruity, woody |

| (E)-β-Ionone | 1494 | 1487 [53] | 192.1514 | C13H20O | 0.85 ± 0.02 b | 0.36 ± 0.11 a | 0.54 ± 0.08 a | Floral: sweet, floral, fruity, woody |

| Aldehydes | ||||||||

| (Z)-2-Heptenal | 956 | 947 [53] | 112.0888 | C7H12O | 0.41 ± 0.03 a | 1.33 ± 0.21 b | -ND | Green: green, fatty |

| Benzaldehyde | 962 | 962 [52] | 106.0419 | C7H6O | 8.44 ± 0.18 c | 1.02 ± 0.05 b | 0.72 ± 0.08 a | Fruity: sweet, bitter, almond, cherry |

| (E,Z)-2,4-Heptadienal | 999 | 990 [52] | 110.0732 | C7H10O | 0.68 ± 0.00 a | 2.60 ± 0.08 b | -ND | Green: green, pungent, fruity, spicy |

| Octanal | 1004 | 998 [53] | 128.1201 | C8H16O | 3.68 ± 0.21 b | 1.89 ± 0.00 a | 1.67 ± 0.00 a | Aldehydic: aldehydic, waxy, citrus, orange peel, green, herbal, fresh, fatty |

| (E,E)-2,4-Heptadienal | 1013 | 1005 [53] | 110.0732 | C7H10O | -ND | 4.62 ± 0.20 b | 0.23 ± 0.03 a | Fatty: fatty, green, oily, aldehydic |

| Phenylacetaldehyde | 1048 | 1036 [53] | 120.0575 | C8H8O | 0.58 ± 0.21 b | 0.08 ± 0.00 a | 0.84 ± 0.00 b | Green: green, sweet, floral, hyacinth, clover, honey, cocoa |

| (E)-2-Octenal | 1060 | 1049 [53] | 126.1045 | C8H14O | 0.36 ± 0.16 | -ND | -ND | Fatty: fresh, cucumber, fatty, green, herbal, banana, waxy, green leafy |

| Nonanal | 1106 | 1103 [52] | 142.1358 | C9H18O | 1.14 ± 0.13 a | 1.19 ± 0.11 a | 1.35 ± 0.14 a | Aldehydic: waxy, aldehydic, rose, fresh, orris, orange peel, fatty, citrus |

| 2,4-Dimethylbenzaldehyde | 1181 | 1180 [55] | 134.0732 | C9H10O | 0.33 ± 0.07 a | -ND | 0.30 ± 0.00 a | Naphthyl: naphthyl, cherry, almond |

| Decanal | 1209 | 1206 [52] | 156.1514 | C10H20O | 1.65 ± 0.19 c | 0.47 ± 0.12 a | 1.04 ± 0.07 b | Aldehydic: sweet, aldehydic, waxy, orange peel, citrus, floral |

| p-Anisaldehyde | 1264 | 1247 [53] | 136.0524 | C8H8O2 | -ND | 0.87 ± 0.03 | -ND | Anisic: sweet, powdery, vanilla, anise, woody, coumarinic, creamy, spicy |

| Esters | ||||||||

| Methyl octanoate | 1126 | 1123 [53] | 158.1307 | C9H18O2 | 0.96 ± 0.05 | -ND | -ND | Waxy: waxy, green, sweet, orange, aldehydic, vegetable, herbal |

| Ethyl octanoate | 1200 | 1196 [53] | 172.1463 | C10H20O2 | 0.32 ± 0.04 a | -ND | 0.38 ± 0.02 a | Waxy: fruity, winey, waxy, sweet, apricot, banana, brandy, pear |

| Ethyl 2-phenylethanoate | 1252 | 1243 [53] | 164.0837 | C10H12O2 | -ND | -ND | 14.03 ± 0.00 | Floral: sweet, floral, honey, rose |

| Methyl dodecanoate | 1527 | 1524 [53] | 214.1933 | C13H26O2 | 0.47 ± 0.00 b | 0.18 ± 0.01 a | 0.17 ± 0.04 a | Waxy: waxy, soapy, creamy, coconut |

| Alcohols | ||||||||

| Heptan-1-ol | 970 | 959 [53] | 116.1201 | C7H16O | 0.75 ± 0.00 | -ND | -ND | Green: musty, pungent, leafy, green, vegetable, fruity, apple, banana |

| Oct-1-en-3-ol | 979 | 974 [53] | 128.1201 | C8H16O | 1.07 ± 0.10 b | 0.11 ± 0.00 a | 0.10 ± 0.03 a | Earthy: earthy, green, oily, vegetable |

| Benzyl alcohol | 1039 | 1026 [53] | 108.0575 | C7H8O | 0.29 ± 0.00 a | 2.05 ± 0.34 b | 2.22 ± 0.09 b | Floral: sweet, floral, fruity, chemical |

| 2-Phenylethanol | 1119 | 1116 [54] | 122.0732 | C8H10O | 1.22 ± 0.00 a | 3.80 ± 0.23 b | 3.83 ± 0.00 b | Floral: sweet, floral, fresh, rose, honey |

| Ketones | ||||||||

| 3-Octanone | 987 | 979 [53] | 128.1201 | C8H16O | 2.72 ± 0.00 | -ND | -ND | Herbal: herbal lavender sweet mushroom, fermented, green, vegetable |

| 6-Methyl-5-heptene-2-one | 988 | 981 [53] | 126.1045 | C8H14O | 2.72 ± 0.00 c | 0.84 ± 0.04 b | 0.42 ± 0.03 a | Citrus: fruity, apple, musty, ketonic, creamy, cheesy, banana |

| 2-Octanone | 992 | 988 [53] | 128.1201 | C8H16O | 0.38 ± 0.14 | -ND | -ND | Earthy: earthy, weedy, natural, woody, herbal, dairy |

| 3-Octen-2-one | 1041 | 1030 [53] | 126.1045 | C8H14O | 0.61 ± 0.12 | -ND | -ND | Earthy: earthy, spicy, herbal, sweet, mushroom, hay, blueberry |

| (E,E)-3,5-octadien-2-one | 1074 | 1068 [56] | 124.0888 | C8H12O | 3.78 ± 0.11 b | -ND | 0.65 ± 0.05 a | Fruity: fruity, green, grassy |

| 2-Nonanone | 1094 | 1087 [53] | 142.1358 | C9H18O | 0.73 ± 0.01 | -ND | -ND | Fruity: fresh, sweet, green, herbal |

| 3,5-Octadien-2-one | 1096 | 1102 [57] | 124.0888 | C8H12O | 0.80 ± 0.16 b | -ND | 0.22 ± 0.00 a | Fatty: fruity, fatty, mushroom |

| 6-Methyl-3,5-heptadien-2-one | 1109 | 1105 [58] | 124.0888 | C8H12O | 0.81 ± 0.08 b | -ND | 0.24 ± 0.06 a | Spicy: green, spicy, cooling, herbal |

| 4-Ketoisophorone | 1149 | 1140 [53] | 152.0837 | C9H12O2 | 1.00 ± 0.03 b | -ND | 0.42 ± 0.05 a | Musty: woody, sweet, tea, tobacco, leafy, citrus, lemon |

| Hexahydrofarnesyl acetone | 1845 | 1836 B | 268.2766 | C13H36O | 0.25 ± 0.04 a | 0.31± 0.09 a | 0.59 ± 0.00 b | Woody: woody, floral, jasmine, green |

| Furan derivatives | ||||||||

| 2-Pentylfuran | 992 | 984 [53] | 138.1045 | C9H14O | 0.35 ± 0.06 b | 0.12 ± 0.02 a | 0.12 ± 0.00 a | Fruity: fruity, green, earthy, beany, vegetable, metallic |

| 3,4-Dimethylfuran-2,5-dione | 1043 | 1038 [59] | 126.0317 | C6H6O3 | -ND | 2.39 ± 0.00 a | 3.17 ± 0.00 b | |

| 2,3-Dihydrobenzofuran | 1226 | 1226 [60] | 120.0575 | C8H8O | -ND | -ND | 0.92 ± 0.06 | |

| Dihydroactinidiolide | 1547 | 1539 [61] | 180.115 | C11H16O2 | 1.30 ±0.01 b | -ND | 1.14 ± 0.07 a | Fruity: ripe apricot, fruity, plum, berry, grape, fruit, tropical fruit, woody |

| Fatty acids | ||||||||

| Hexanoic acid | 1012 | 1020 [62] | 116.0837 | C6H12O2 | 1.92 ± 0.15 b | 4.64 ± 0.00 c | 1.43 ± 0.15 a | Fatty: sour, fatty, sweaty, cheesy |

| Heptanoic acid | 1092 | 1097 [63] | 130.0994 | C7H14O2 | 0.23 ± 0.00 a | 0.94 ± 0.00 c | 0.56 ± 0.00 b | Cheesy: waxy, fermented, fruity |

| Octanoic acid | 1194 | 1179 [62] | 144.115 | C8H16O2 | 5.99 ± 0.23 c | 2.18 ± 0.00 a | 4.32 ± 0.00 b | Fatty: fatty, waxy, rancid, oily, vegetable, cheesy |

| Nonanoic acid | 1276 | 1273 [48] | 158.1307 | C9H18O2 | 0.33 ± 0.04 a | 0.53 ± 0.00 b | 0.30 ± 0.08 a | Waxy: waxy, cheesy, dairy |

| Dodecanoic acid | 1569 | 1565 [53] | 186.162 | C12H24O2 | -ND | 1.16 ± 0.00 b | 1.06 ±0.00 a | Fatty: fatty, coconut, bay |

| Lactones | ||||||||

| γ-Valerolactone | 957 | 958 [64] | 100.0524 | C5H8O2 | 0.30 ± 0.11 a | 0.91 ± 0.00 c | 0.60 ± 0.02 b | Herbal: herbal, warm, tobacco, woody |

| d-Pantolactone | 1042 | 1032 B | 130.0630 | C6H10O3 | -ND | 2.18 ± 0.11 a | 3.17 ± 0.00 b | |

| γ-Caprolactone | 1060 | 1062 [64] | 114.0681 | C6H10O2 | 0.36 ± 0.16 a | -ND | 0.68 ± 0.00 b | Tonka: coconut, sweet, tobacco |

| β-Hydroxy-γ-butyrolactone | 1180 | 1185 B | 102.0317 | C4H6O3 | -ND | 2.89 ± 0.00 a | 2.36 ± 0.00 b | |

| γ-Nonalactone | 1369 | 1363 [65] | 156.1150 | C9H16O2 | -ND | 0.44 ± 0.00 | -ND | Coconut: coconut, creamy, waxy, sweet, buttery, oily |

| Others (identified) | ||||||||

| Maltol | 1121 | 1110 [66] | 126.0317 | C6H6O3 | -ND | 1.03 ± 0.00 b | 0.63 ± 0.00 a | Caramellic: sweet, caramellic, cotton candy, jammy, fruity, baked bread |

| N-Formylmorpholine | 1135 | 1133 [67] | 115.0633 | C5H9NO2 | -ND | 1.56 ± 0.17 | -ND | Mild |

| Benzeneacetonitrile | 1146 | 1134 [53] | 117.0578 | C8H7N | 0.67 ± 0.16 a | 0.58 ± 0.00 a | 1.57 ± 0.00 b | |

| 2,3-Dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl-4h-pyran-4-one | 1150 | 1140 [68] | 144.0423 | C6H8O4 | -ND | 0.28 ± 0.00 a | 1.90 ± 0.08 b | |

| 1-Acetylpyrrolidine | 1179 | 1162 B | 113.0841 | C6H11NO | 0.13 ± 0.01 a | 0.47 ± 0.09 b | 0.26 ± 0.00 a | |

| Butyl diglycol | 1194 | 1198 [69] | 162.1256 | C8H18O3 | -ND | 0.76 ± 0.06 a | 1.05 ± 0.00 b | |

| Benzoic acid | 1197 | 1196 [70] | 122.0368 | C7H6O2 | -ND | 2.98 ± 0.00 b | 1.05 ± 0.00 a | Balsamic: balsamic, urine |

| Benzenacetic acid | 1262 | 1255 [62] | 136.0524 | C8H8O2 | -ND | 1.81 ± 0.00 b | 0.14 ± 0.00 a | |

| 2,4,6,8-tetramethylundecene | 1342 | 1330 B | 210.2348 | C15H30 | 0.20 ± 0.10 a | 0.47 ± 0.00 b | 0.24 ± 0.05 a | |

| Total GC peak area AU × 106 | 401.65 ± 43.07 | 294.95 ± 26.18 | 399.18 ± 28.16 | |||||

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Plant Material and Reagents

3.2. SFE-CO2 Extraction of T. officinale Flowers

3.3. In Vitro Antioxidant Capacity Assessment

3.4. Total Phenolic Content (TPC) Assessment

3.5. Total Flavonoid Content (TFC) Assessment

3.6. β-Carotene Content Assessment

3.7. UV Absorbance Test and Sun Protection Factor (SPF) Determination

3.8. Determination of Volatile Compound Composition by GC × GC-TOF-MS

3.9. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ikram, A.; Khan, R.; Kauser, S.; Khan, A.A.; Arshad, M.T.; Ahmad, M. Taraxacum Officinale (Dandelion). In Edible Flowers; Gupta, A.K., Kumar, V., Naik, B., Mishra, P., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2024; pp. 281–300. ISBN 978-0-443-13769-3. [Google Scholar]

- Lis, B.; Olas, B. Pro-Health Activity of Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale L.) and Its Food Products—History and Present. J. Funct. Foods 2019, 59, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruszecki, R.; Walasek-Janusz, M.; Caruso, G.; Pokluda, R.; Tallarita, A.V.; Golubkina, N.; Sękara, A. Multilateral Use of Dandelion in Folk Medicine of Central-Eastern Europe. Plants 2025, 14, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Sun, J.; Liu, M.; Zhang, X.; Kong, L.; Ma, L.; Jiang, S.; Liu, X.; Ma, W. Botany, Traditional Use, Phytochemistry, Pharmacology and Quality Control of Taraxaci Herba: Comprehensive Review. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, F.; Deng, X.; Yu, X.; Wang, W.; Yan, W.; Zhao, X.; Wang, X.; Bai, C.; Wang, Z.; Han, L. Taraxacum: A Review of Ethnopharmacology, Phytochemistry and Pharmacological Activity. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2024, 52, 183–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grauso, L.; Emrick, S.; de Falco, B.; Lanzotti, V.; Bonanomi, G. Common Dandelion: A Review of Its Botanical, Phytochemical and Pharmacological Profiles. Phytochem. Rev. 2019, 18, 1115–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Castejon, M.; Visioli, F.; Rodriguez-Casado, A. Diverse Biological Activities of Dandelion. Nutr. Rev. 2012, 70, 534–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Chen, Y.; Sun-Waterhouse, D. The Potential of Dandelion in the Fight against Gastrointestinal Diseases: A Review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2022, 293, 115272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, X.; Shi, W.; Shen, T.; Cheng, X.; Wan, Q.; Fan, M.; Hu, D. Research Updates and Advances on Flavonoids Derived from Dandelion and Their Antioxidant Activities. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q.; Xing, Q.; Liu, Z.; Zou, Y.; Liu, X.; Xia, H. The Phytochemical and Pharmacological Profile of Dandelion. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 179, 117334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, M.; Zhang, X.; Song, H.; Zhang, Y. Dandelion (Taraxacum Genus): A Review of Chemical Constituents and Pharmacological Effects. Molecules 2023, 28, 5022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurinjak Tušek, A.; Benković, M.; Belščak Cvitanović, A.; Valinger, D.; Jurina, T.; Gajdoš Kljusurić, J. Kinetics and Thermodynamics of the Solid-Liquid Extraction Process of Total Polyphenols, Antioxidants and Extraction Yield from Asteraceae Plants. Ind. Crops Prod. 2016, 91, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shi, Y.; Zou, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhai, B.; Guo, D.; Sun, J.; Luan, F. Extraction, Purification, Structural Features, Biological Activities, Modifications, and Applications from Taraxacum Mongolicum Polysaccharides: A Review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 259, 129193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, M.; Erşatır, M.; Poyraz, S.; Amangeldinova, M.; Kudrina, N.O.; Terletskaya, N.V. Green Extraction of Plant Materials Using Supercritical CO2: Insights into Methods, Analysis, and Bioactivity. Plants 2024, 13, 2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheriyan, B.V.; Karunakar, K.K.; Anandakumar, R.; Murugathirumal, A.; Kumar, A.S. Eco-Friendly Extraction Technologies: A Comprehensive Review of Modern Green Analytical Methods. Sust. Chem. Clim. Act. 2025, 6, 100054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, M.E.M.; Gaspar, M.C.; de Sousa, H.C. Supercritical Fluid Technology for Agrifood Materials Processing. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2023, 50, 100983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaw, K.-Y.; Parat, M.-O.; Shaw, P.N.; Falconer, J.R. Solvent Supercritical Fluid Technologies to Extract Bioactive Compounds from Natural Sources: A Review. Molecules 2017, 22, 1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milovanovic, S.; Grzegorczyk, A.; Swiatek, L.; Boguszewska, A.; Kowalski, R.; Tyskiewicz, K.; Konkol, M. Phenolic, Tocopherol, and Essential Fatty Acid-Rich Extracts from Dandelion Seeds: Chemical Composition and Biological Activity. Food Bioprod. Process. 2023, 142, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milovanovic, S.; Tyśkiewicz, K.; Konkol, M.; Grzegorczyk, A.; Salwa, K.; Świątek, Ł. Optimizing Green Extraction Methods for Maximizing the Biological Potential of Dandelion, Milk Thistle, and Chamomile Seed Extracts. Foods 2024, 13, 3907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milovanovic, S.; Grzegorczyk, A.; Świątek, Ł.; Dębczak, A.; Tyskiewicz, K.; Konkol, M. Dandelion Seeds as a New and Valuable Source of Bioactive Extracts Obtained Using the Supercritical Fluid Extraction Technique. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2022, 29, 100796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simándi, B.; Kristo, S.T.; Kéry, Á.; Selmeczi, L.K.; Kmecz, I.; Kemény, S. Supercritical Fluid Extraction of Dandelion Leaves. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2002, 23, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoss, K.; Kočevar Glavač, N.; Dolenc Koce, J.; Anžlovar, S. Supercritical CO2 Plant Extracts Show Antifungal Activities against Crop-Borne Fungi. Molecules 2022, 27, 1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Li, A.; Li, S.; Tang, J.; Li, L.; Xiong, L. Natural Components in Sunscreens: Topical Formulations with Sun Protection Factor (SPF). Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 134, 111161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemat, F.; Vian, M.A.; Fabiano-Tixier, A.-S.; Nutrizio, M.; Jambrak, A.R.; Munekata, P.E.S.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Barba, F.J.; Binello, A.; Cravotto, G. A Review of Sustainable and Intensified Techniques for Extraction of Food and Natural Products. Green Chem. 2020, 22, 2325–2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azmir, J.; Zaidul, I.S.M.; Rahman, M.M.; Sharif, K.M.; Mohamed, A.; Sahena, F.; Jahurul, M.H.A.; Ghafoor, K.; Norulaini, N.A.N.; Omar, A.K.M. Techniques for Extraction of Bioactive Compounds from Plant Materials: A Review. J. Food Eng. 2013, 117, 426–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovová, H. Steps of Supercritical Fluid Extraction of Natural Products and Their Characteristic Times. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2012, 66, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apak, R.; Güçlü, K.; Demirata, B.; Özyürek, M.; Çelik, S.E.; Bektaşoğlu, B.; Berker, K.I.; Özyurt, D. Comparative Evaluation of Various Total Antioxidant Capacity Assays Applied to Phenolic Compounds with the CUPRAC Assay. Molecules 2007, 12, 1496–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, J.; Edwards, D.; Pun, S.; Williams, D. Evaluation of Antioxidant Capacity (ABTS and CUPRAC) and Total Phenolic Content (Folin-Ciocalteu) Assays of Selected Fruit, Vegetables, and Spices. Int. J. Food Sci. 2022, 2022, 2581470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jedrejek, D.; Pawelec, S. Comprehensive Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis of Flavonoids in Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) Flowers and Food Products. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 17368–17376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Almeida, L.C.; Salvador, M.R.; Pinheiro-Sant’Ana, H.M.; Della Lucia, C.M.; Teixeira, R.D.B.L.; Cardoso, L.D.M. Proximate Composition and Characterization of the Vitamins and Minerals of Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) from the Middle Doce River Region—Minas Gerais, Brazil. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biel, W.; Jaroszewska, A.; Łysoń, E.; Telesiński, A. The Chemical Composition and Antioxidant Properties of Common Dandelion Leaves Compared to Sea Buckthorn. Can. J. Plant Sci. 2017, 97, 1165–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, T.H.; Loh, C.H.; Inbaraj, B.S.; Chen, B.H. Determination of Carotenoids in Taraxacum formosanum by HPLC–DAD–APCI-MS and Preparation by Column Chromatography. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2012, 66, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Kitts, D.D. Antioxidant, Prooxidant, and Cytotoxic Activities of Solvent-Fractionated Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) Flower Extracts in Vitro. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelizzo, M.; Zattra, E.; Nicolosi, P.; Peserico, A.; Garoli, D.; Alaibac, M. In Vitro Evaluation of Sunscreens: An Update for the Clinicians. Int. Sch. Res. Not. 2012, 2012, 352135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission Recommendation of 22 September 2006 on the efficacy of sunscreen products and the claims made relating thereto (2006/647/EC). Off. J. Eur. Union 2006, 265, 39–43.

- Milutinov, J.; Pavlović, N.; Ćirin, D.; Atanacković Krstonošić, M.; Krstonošić, V. The Potential of Natural Compounds in UV Protection Products. Molecules 2024, 29, 5409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Filho, J.M.T.A.; Sampaio, P.A.; Pereira, E.C.V.; de Junior, R.G.O.; Silva, F.S.; Da Silva Almeida, J.R.G.; Rolim, L.A.; Nunes, X.P.; da Cruz Araujo, E.C. Flavonoids as Photoprotective Agents: A Systematic Review. J. Med. Plants Res. 2016, 10, 848–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agati, G.; Tattini, M. Multiple Functional Roles of Flavonoids in Photoprotection. New Phytol. 2010, 186, 786–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Chong, L.; Huang, T.; Ma, Y.; Li, Y.; Ding, H. Natural Products and Extracts from Plants as Natural UV Filters for Sunscreens: A Review. Anim. Model. Exp. Med. 2023, 6, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flieger, J.; Raszewska-Famielec, M.; Radzikowska-Büchner, E.; Flieger, W. Skin Protection by Carotenoid Pigments. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Li, S. Dandelion Extracts Protect Human Skin Fibroblasts from UVB Damage and Cellular Senescence. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2015, 2015, 619560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, P.; Huang, L.; Zhang, C.; Ding, S.; Deng, Y.; Wang, X. Skin-Care Effects of Dandelion Leaf Extract and Stem Extract: Antioxidant Properties, Tyrosinase Inhibitory and Molecular Docking Simulations. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2018, 111, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolvachai, Y.; Amaral, M.S.S.; Herron, R.; Marriott, P.J. Solid Phase Microextraction for Quantitative Analysis—Expectations beyond Design? Green Anal. Chem. 2023, 4, 100048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortini, M.; Migliorini, M.; Cherubini, C.; Cecchi, L.; Calamai, L. Multiple Internal Standard Normalization for Improving HS-SPME-GC-MS Quantitation in Virgin Olive Oil Volatile Organic Compounds (VOO-VOCs) Profile. Talanta 2017, 165, 641–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burzynski-Chang, E.A.; Ryona, I.; Reisch, B.I.; Gonda, I.; Foolad, M.R.; Giovannoni, J.J.; Sacks, G.L. HS-SPME-GC-MS Analyses of Volatiles in Plant Populations—Quantitating Compound × Individual Matrix Effects. Molecules 2018, 23, 2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.N.; Pawliszyn, J. Effect of Binding Components in Complex Sample Matrices on Recovery in Direct Immersion Solid-Phase Microextraction: Friends or Foe? Anal. Chem. 2018, 90, 2430–2433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouyahya, A.; Mechchate, H.; Benali, T.; Ghchime, R.; Charfi, S.; Balahbib, A.; Burkov, P.; Shariati, M.A.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Omari, N.E. Health Benefits and Pharmacological Properties of Carvone. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerković, I.; Marijanović, Z.; Kranjac, M.; Radonić, A. Comparison of Different Methodologies for Detailed Screening of Taraxacum officinale Honey Volatiles. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2015, 10, 1934578X1501000238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegmund, B.; Urdl, K.; Jurek, A.; Leitner, E. “More than Honey”: Investigation on Volatiles from Monovarietal Honeys Using New Analytical and Sensory Approaches. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 2432–2442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paula Dionísio, A.; Molina, G.; Souza de Carvalho, D.; dos Santos, R.; Bicas, J.L.; Pastore, G.M. 11-Natural Flavourings from Biotechnology for Foods and Beverages. In Natural Food Additives, Ingredients and Flavourings; Baines, D., Seal, R., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing Series in Food Science, Technology and Nutrition; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2012; pp. 231–259. ISBN 978-1-84569-811-9. [Google Scholar]

- Bylka, W.; Matlawska, I.; Frański, R. Essential Oil Composition of Taraxacum officinale. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2010, 32, 231–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flamini, G.; Cioni, P.L.; Morelli, I. Differences in the Fragrances of Pollen, Leaves, and Floral Parts of Garland (Chrysanthemum coronarium) and Composition of the Essential Oils from Flowerheads and Leaves. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 2267–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, R.P. Identification of Essential Oil Components by Gas Chromatography Mass Spectroscopy; Allured Publishing Corporation: Carol Stream, IL, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-1-932633-21-4. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, C.; Li, X.; Liang, Y.; Fang, H.; Huang, L.-F.; Guo, F. Comparative Analysis of Chemical Components of Essential Oils from Different Samples of Rhododendron with the Help of Chemometrics Methods. Chemometr. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2006, 82, 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flamini, G.; Cioni, P.L.; Morelli, I. Essential Oils of Galeopsis pubescens and G. tetrahit from Tuscany (Italy). Flavour Fragr. J. 2004, 19, 327–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaulieu, J.C.; Grimm, C.C. Identification of Volatile Compounds in Cantaloupe at Various Developmental Stages Using Solid Phase Microextraction. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 1345–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pino, J.A.; Marbot, R.; Payo, A.; Chao, D.; Herrera, P. Aromatic Plants from Western Cuba VII. Composition of the Leaf Oils of Psidium wrightii Krug et Urb., Lantana involucrata L., Cinnamomum montanum (Sw.) Berchtold et J. Persl. And Caesalpinia violacea (Mill.) Standley. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2006, 18, 170–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiming, X.; Haidong, C.; Huixian, Z.; Daqiang, Y. Chemical Composition of Essential Oils of Two Submerged Macrophytes, Ceratophyllum demersum L. and Vallisneria spiralis L. Flavour. Fragr. J. 2006, 21, 524–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandi, F.; Bar, E.; Mourgues, F.; Horváth, G.; Turcsi, E.; Giuliano, G.; Liverani, A.; Tartarini, S.; Lewinsohn, E.; Rosati, C. Study of “Redhaven” Peach and Its White-Fleshed Mutant Suggests a Key Role of CCD4 Carotenoid Dioxygenase in Carotenoid and Norisoprenoid Volatile Metabolism. BMC Plant Biol. 2011, 11, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sayed, A.M.; Heppelthwaite, V.J.; Manning, L.M.; Gibb, A.R.; Suckling, D.M. Volatile Constituents of Fermented Sugar Baits and Their Attraction to Lepidopteran Species. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 953–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, J.; Xu, Y.; Duan, H.; Fan, W.; Zhao, G. Extraction, Preparation and Identification of Volatile Compounds in Changyu XO Brandy. Chin. J. Chromatogr. 2008, 26, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colahan-Sederstrom, P.M.; Peterson, D.G. Inhibition of Key Aroma Compound Generated during Ultrahigh-Temperature Processing of Bovine Milk via Epicatechin Addition. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 398–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttery, R.G.; Ling, L.C.; Stern, D.J. Studies on Popcorn Aroma and Flavor Volatiles. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1997, 45, 837–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Esteban, M.; Ansorena, D.; Astiasarán, I.; Ruiz, J. Study of the Effect of Different Fiber Coatings and Extraction Conditions on Dry Cured Ham Volatile Compounds Extracted by Solid-Phase Microextraction (SPME). Talanta 2004, 64, 458–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Fan, W.; Qian, M.C. Characterization of Aroma Compounds in Apple Cider Using Solvent-Assisted Flavor Evaporation and Headspace Solid-Phase Microextraction. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 3051–3057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadel, H.H.M.; Abdel Mageed, M.A.; Abdel Samad, A.K.M.E.; Lotfy, S.N. Cocoa Substitute: Evaluation of Sensory Qualities and Flavour Stability. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2006, 223, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machiels, D. Gas Chromatography-Olfactometry Analysis of the Volatile Compounds of Two Commercial Irish Beef Meats. Talanta 2003, 60, 755–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Göğüş, F.; Özel, M.Z.; Lewis, A.C. The Effect of Various Drying Techniques on Apricot Volatiles Analysed Using Direct Thermal Desorption-GC–TOF/MS. Talanta 2007, 73, 321–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varlet, V.; Knockaert, C.; Prost, C.; Serot, T. Comparison of Odor-Active Volatile Compounds of Fresh and Smoked Salmon. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 3391–3401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rapior, S.; Breheret, S.; Talou, T.; Pélissier, Y.; Bessière, J.-M. The Anise-like Odor of Clitocybe odora, Lentinellus cochleatus and Agaricus essettei. Mycologia 2002, 94, 373–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, I.; Petkova, N.; Tumbarski, J.; Dincheva, I.; Badjakov, I.; Denev, P.; Pavlov, A. GC-MS Characterization of n-Hexane Soluble Fraction from Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale Weber Ex F.H. Wigg.) Aerial Parts and Its Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Properties. Z. Naturforsch. C. J. Biosci. 2018, 73, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Chen, T.; Ye, S.; Gao, S.; Dong, Y. Comparative Analysis with GC–MS of Fatty Acids and Volatile Compounds of Taraxacum kok-saghyz Rodin and Taraxacum officinale as Edible Resource Plants. Separations 2022, 9, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitrytė, V.; Narkevičiutė, A.; Tamkutė, L.; Syrpas, M.; Pukalskienė, M.; Venskutonis, P. Consecutive High-Pressure and Enzyme Assisted Fractionation of Blackberry (Rubus fruticosus L.) Pomace into Functional Ingredients: Process Optimization and Product Characterization. Food Chem. 2020, 312, 126072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitrytė, V.; Laurinavičienė, A.; Syrpas, M.; Pukalskas, A.; Venskutonis, P. Modeling and Optimization of Supercritical Carbon Dioxide Extraction for Isolation of Valuable Lipophilic Constituents from Elderberry (Sambucus nigra L.) Pomace. J. CO2 Util. 2020, 35, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagybákay, N.; Sarapinaitė, L.; Syrpas, M.; Venskutonis, P.; Kitrytė-Syrpa, V. Optimization of Pressurized Ethanol Extraction for Efficient Recovery of Hyperoside and Other Valuable Polar Antioxidant-Rich Extracts from Betula pendula Roth Leaves. Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 205, 117565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitrytė, V.; Kavaliauskaitė, A.; Tamkutė, L.; Pukalskienė, M.; Syrpas, M.; Venskutonis, P. Zero Waste Biorefining of Lingonberry (Vaccinium vitis-idaea L.) Pomace into Functional Ingredients by Consecutive High Pressure and Enzyme Assisted Extractions with Green Solvents. Food Chem. 2020, 322, 126767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vongsak, B.; Sithisarn, P.; Mangmool, S.; Thongpraditchote, S.; Wongkrajang, Y.; Gritsanapan, W. Maximizing Total Phenolics, Total Flavonoids Contents and Antioxidant Activity of Moringa oleifera Leaf Extract by the Appropriate Extraction Method. Ind. Crops Prod. 2013, 44, 566–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, A.K.; Sahoo, J.; Chatli, M.K. A Simple UV-Vis Spectrophotometric Method for Determination of β-Carotene Content in Raw Carrot, Sweet Potato and Supplemented Chicken Meat Nuggets. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 44, 1809–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayre, R.M.; Agin, P.P.; LeVee, G.J.; Marlowe, E. A Comparison of In Vivo and In Vitro Testing of Sunscreening Formulas. Photochem. Photobiol. 1979, 29, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagybákay, N.E.; Syrpas, M.; Vilimaitė, V.; Tamkutė, L.; Pukalskas, A.; Venskutonis, P.R.; Kitrytė, V. Optimized Supercritical CO2 Extraction Enhances the Recovery of Valuable Lipophilic Antioxidants and Other Constituents from Dual-Purpose Hop (Humulus lupulus L.) Variety Ella. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Samples | SFE-CO2 | SFE-CO2 + 5% EtOH | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 40 °C, 35 MPa, 195 min | 40 °C, 35 MPa, 195 min | ||

| In vitro antioxidant activity: | |||

| TEACCUPRAC | mg TE/g E | 84.42 ± 0.50 a | 169.78 ± 0.99 b |

| mg TE/g DF | 4.06 ± 0.02 a | 12.29 ± 0.07 b | |

| TEACABTS | mg TE/g E | 17.54 ± 0.60 a | 193.80 ± 0.65 b |

| mg TE/g DF | 0.84 ± 0.03 a | 14.03 ± 0.05 b | |

| Total phenolic and flavonoid content: | |||

| TPC | mg GAE/g E | 29.12 ± 0.52 a | 91.30 ± 1.07 b |

| mg GAE/g DF | 1.40 ± 0.02 a | 6.61 ± 0.08 b | |

| TFC | mg QE/g E | 13.11 ± 0.22 a | 23.91 ± 0.39 b |

| mg QE/g DF | 0.63 ± 0.03 a | 1.73 ± 0.03 b | |

| Pigment content: | |||

| β-carotene | mg/g E | 28.16 ± 0.13 a | 44.71 ± 0.24 b |

| mg/g DF | 1.35 ± 0.01 a | 3.24 ± 0.02 ba | |

| Extract | Concentration (mg/mL) | Sun Protection Factor (SPF) | UV-B Absorption % |

|---|---|---|---|

| SFE-CO2 (35 MPa, 40 °C, 195 min) | 0.05 | 0.83 ± 0.03 a | - |

| 0.10 | 1.63 ± 0.05 ab | 39 | |

| 0.25 | 3.84 ± 0.12 cd | 74 | |

| 0.50 | 7.26 ± 0.24 f | 86 | |

| 1.00 | 13.92 ± 0.45 g | 93 | |

| SFE-CO2 + 5% EtOH (35 MPa, 40 °C, 195 min) | 0.05 | 2.96 ± 0.10 c | 66 |

| 0.10 | 5.62 ± 0.18 e | 82 | |

| 0.25 | 13.53 ± 0.44 g | 93 | |

| 0.50 | 26.62 ± 0.86 h | 96 | |

| 1.00 | 49.51 ± 1.61 i | 98 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sutkaitienė, J.; Syrpas, M.; Venskutonis, P.R.; Kitrytė-Syrpa, V. In Vitro Antioxidant, Photoprotective, and Volatile Compound Profile of Supercritical CO2 Extracts from Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale L.) Flowers. Plants 2026, 15, 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010099

Sutkaitienė J, Syrpas M, Venskutonis PR, Kitrytė-Syrpa V. In Vitro Antioxidant, Photoprotective, and Volatile Compound Profile of Supercritical CO2 Extracts from Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale L.) Flowers. Plants. 2026; 15(1):99. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010099

Chicago/Turabian StyleSutkaitienė, Janina, Michail Syrpas, Petras Rimantas Venskutonis, and Vaida Kitrytė-Syrpa. 2026. "In Vitro Antioxidant, Photoprotective, and Volatile Compound Profile of Supercritical CO2 Extracts from Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale L.) Flowers" Plants 15, no. 1: 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010099

APA StyleSutkaitienė, J., Syrpas, M., Venskutonis, P. R., & Kitrytė-Syrpa, V. (2026). In Vitro Antioxidant, Photoprotective, and Volatile Compound Profile of Supercritical CO2 Extracts from Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale L.) Flowers. Plants, 15(1), 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010099