Essential Oil of Xylopia frutescens Controls Rice Sheath Blight Without Harming the Beneficial Biocontrol Agent Trichoderma asperellum

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Chemical Characterization of Xylopia frutescens Essential Oil

2.2. Sclerotia Germination and Mycelial Growth of Rhizoctonia solani in Response to Increasing Concentrations of Xylopia frutescens Essential Oil

2.3. Molecular Docking Study of Xylopia frutescens Essential Oil

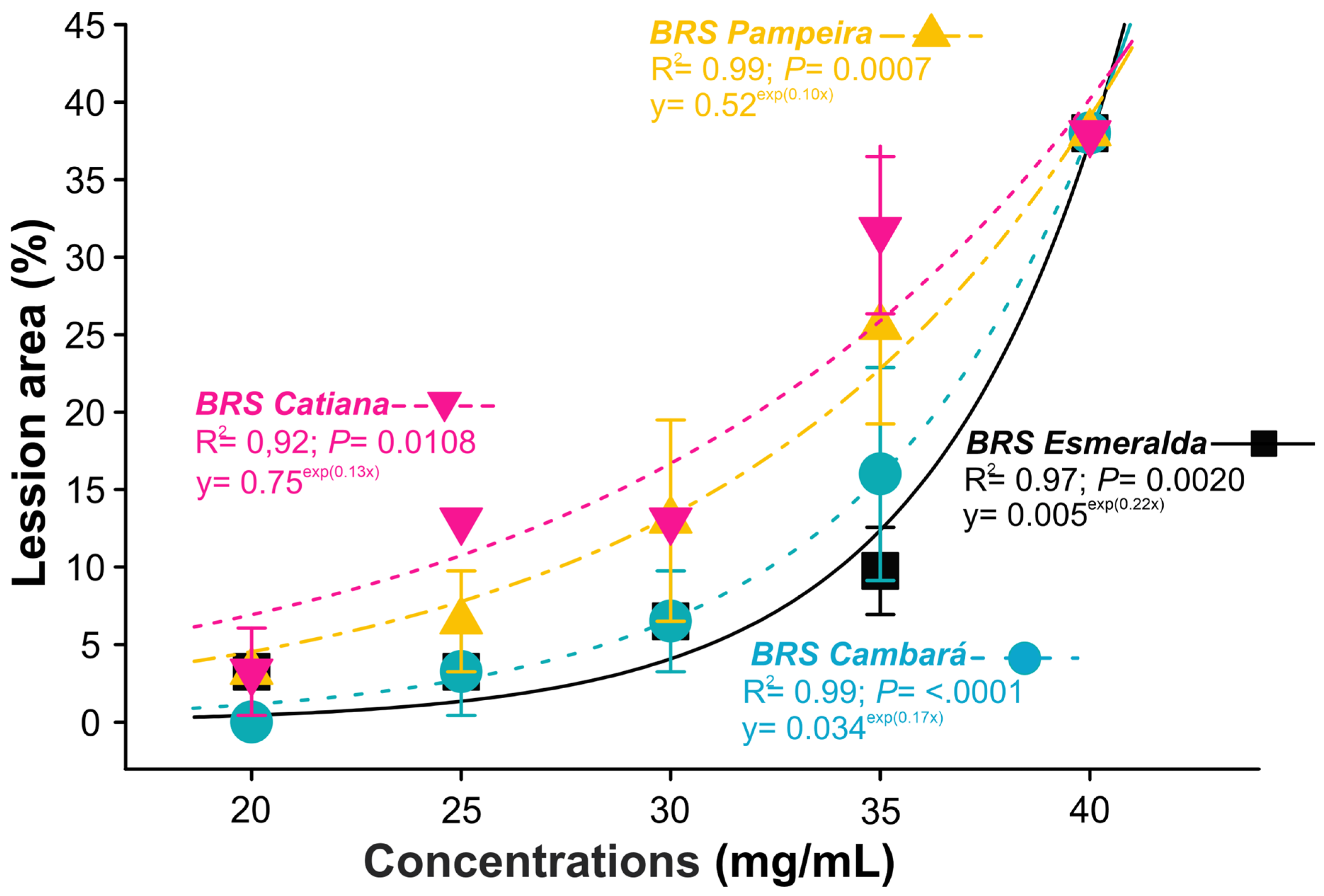

2.4. Effect of Xylopia frutescens Essential Oil on Rice Plant Phytotoxicity

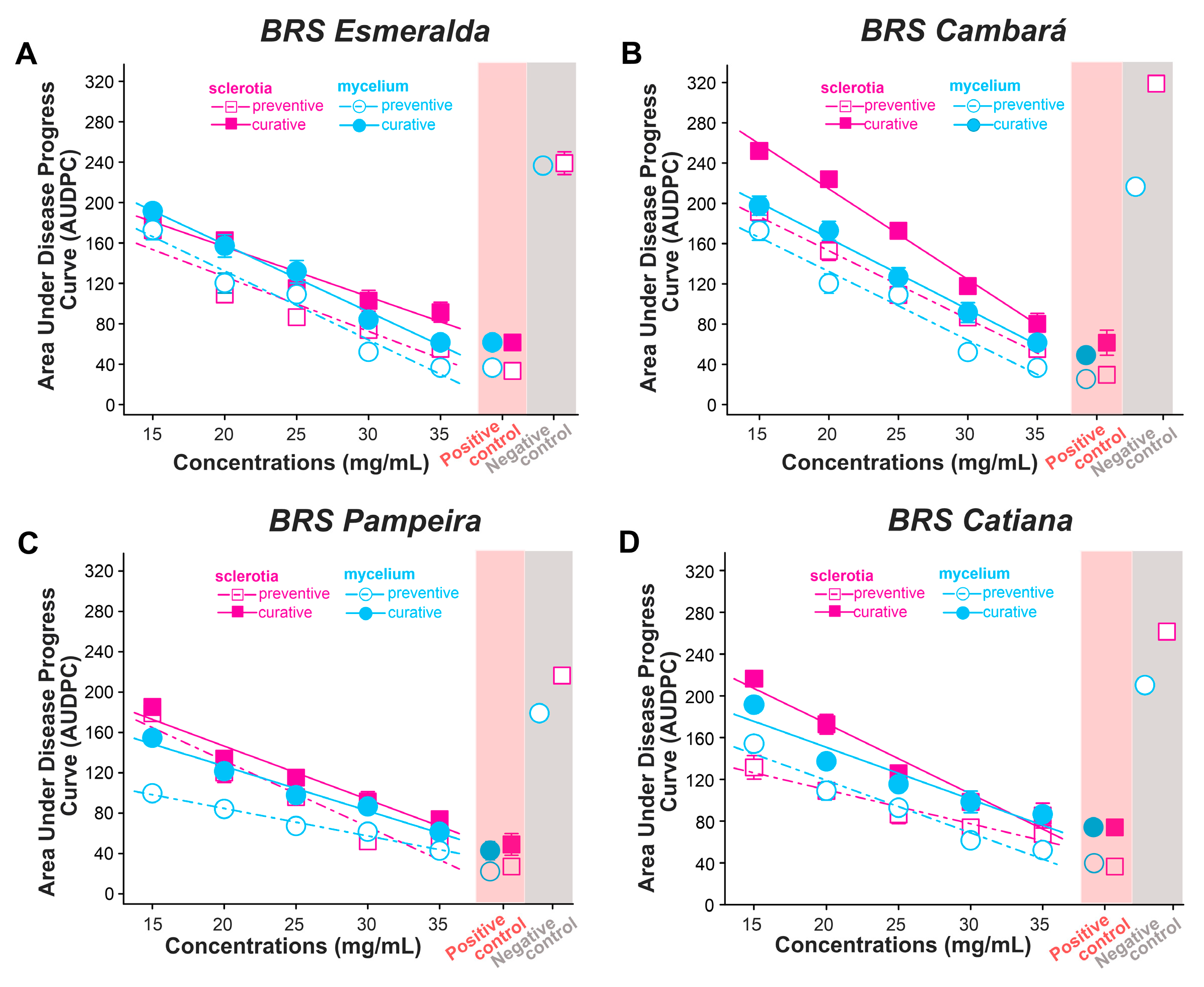

2.5. Effect of Xylopia frutescens Essential Oil on the Preventive and Curative Control of Sheath Blight Caused by Rhizoctonia solani

2.6. Effect of Xylopia frutescens Essential Oil on the Non-Target Organism Trichoderma asperellum

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Pathogen Isolation

4.2. Collection, Extraction, and Chemical Characterization of Xylopia frutescens Essential Oil

4.3. Antifungal Xylopia frutescens Essential Oil Antifungal Potential Against Rhizoctonia solani

4.4. Xylopia frutescens Essential Oil Molecular Docking

4.5. Phytotoxicity of Xylopia frutescens Essential Oil on Rice Plants

4.6. Use of Xylopia frutescens Essential Oil in the Preventive and Curative Control of Rice Sheath Blight

4.7. Assay of the Effect of Xylopia frutescens on Trichoderma asperellum

4.8. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GC-MS | Gas chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry |

| GalNAc | N-acetylgalactosamine |

References

- Paterson, G. Food Outlook: Biannual Report on Global Food Markets. Interaction 2024, 52, 27. [Google Scholar]

- Bandumula, N. Rice production in Asia: Key to global food security. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. India Sect. B Biol. Sci. 2018, 88, 1323–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, D.; Robson, G.D.; Trinci, A.P. 21st Century Guidebook to Fungi; Volume Second; Cambridge University Press: Manchester, UK, 2020; p. 610. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, N.; Yan, J.; Liang, Y.; Shi, Y.; He, Z.; Wu, Y.; Zeng, Q.; Liu, X.; Peng, J. Resistance genes and their interactions with bacterial blight/leaf streak pathogens (Xanthomonas oryzae) in rice (Oryza sativa L.)—An updated review. Rice 2020, 13, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Yan, S.; Li, Y.; Li, G.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, S.; Su, J.; Cui, Z.; Huo, J.; Sun, Y. Defense-related enzyme activities and metabolomic analysis reveal differentially accumulated metabolites and response pathways for sheath blight resistance in rice. Plants 2024, 13, 3554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhaskar Rao, T.; Chopperla, R.; Prathi, N.B.; Balakrishnan, M.; Prakasam, V.; Laha, G.S.; Balachandran, S.M.; Mangrauthia, S.K. A comprehensive gene expression profile of pectin degradation enzymes reveals the molecular events during cell wall degradation and pathogenesis of rice sheath blight pathogen Rhizoctonia solani AG1-IA. J. Fungi 2020, 6, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molla, K.A.; Karmakar, S.; Molla, J.; Bajaj, P.; Varshney, R.K.; Datta, S.K.; Datta, K. Understanding sheath blight resistance in rice: The road behind and the road ahead. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2020, 18, 895–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, G.; Liang, E.; Lan, X.; Li, Q.; Qian, J.; Tao, H.; Zhang, M.; Xiao, N.; Zuo, S.; Chen, J. ZmPGIP3 gene encodes a polygalacturonase-inhibiting protein that enhances resistance to sheath blight in rice. Phytopathology 2019, 109, 1732–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, A.; Lin, R.; Zhang, D.; Qin, P.; Xu, L.; Ai, P.; Ding, L.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Y. The evolution and pathogenic mechanisms of the rice sheath blight pathogen. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groth, D.E.; Bond, J. Effects of cultivars and fungicides on rice sheath blight, yield, and quality. Plant Dis. 2007, 91, 1647–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Ahlawat, S.; Chauhan, R.; Kumar, A.; Singh, R.; Kumar, A. In vitro and field efficacy of fungicides against sheath blight of rice and post-harvest fungicide residue in soil, husk, and brown rice using gas chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2018, 190, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Mazumdar, P.; Harikrishna, J.A.; Babu, S. Sheath blight of rice: A review and identification of priorities for future research. Planta 2019, 250, 1387–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Rahman, T.F.; Abdel-Megeed, A.; Salem, M.Z. Characterization and control of Rhizoctonia solani affecting lucky bamboo (Dracaena sanderiana hort. ex. Mast.) using some bioagents. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 6691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yan, J.; Zhao, L.; Luo, L.; Li, C.; Yang, G. Effects of chemical and biological fungicide applications on sexual sporulation of Rhizoctonia solani AG-3 TB on tobacco. Life 2024, 14, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, M.C.; Hawkins, N.J.; Sanglard, D.; Gurr, S.J. Worldwide emergence of resistance to antifungal drugs challenges human health and food security. Science 2018, 360, 739–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, N.J.; Bass, C.; Dixon, A.; Neve, P. The evolutionary origins of pesticide resistance. Biol. Rev. 2019, 94, 135–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, T.-F.; Shen, Y.-M.; Huang, J.-H.; Tsai, J.-N.; Lu, M.-T.; Lin, C.-P. Insights into grape ripe rot: A focus on the Colletotrichum gloeosporioides species complex and its management strategies. Plants 2023, 12, 2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, T.; Danishuddin; Tamanna, N.T.; Matin, M.N.; Barai, H.R.; Haque, M.A. Resistance mechanisms of plant pathogenic fungi to fungicide, environmental impacts of fungicides, and sustainable solutions. Plants 2024, 13, 2737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Cheng, Y.; Liu, Y.; Shi, X.; Zhang, T.; Qin, W. Characterization and fungicides sensitivity of Colletotrichum species causing Hydrangea macrophylla anthracnose in Beijing, China. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 15, 1504135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Li, Z.; Liu, J.; Shen, Z.; Gao, G.; Zhang, Q.; He, Y. Development and evaluation of improved lines with broad-spectrum resistance to rice blast using nine resistance genes. Rice 2019, 12, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mengistie, B.T.; Ray, R.L.; Iyanda, A. Environmental and Human Health Impacts of Agricultural Pesticides on BIPOC Communities in the United States: A Review from an Environmental Justice Perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavalcante, A.L.A.; Negreiros, A.M.P.; Melo, N.J.d.A.; Santos, F.J.Q.; Soares Silva, C.S.A.; Pinto, P.S.L.; Khan, S.; Sales, I.M.M.; Sales Júnior, R. Adaptability and sensitivity of Trichoderma spp. isolates to environmental factors and fungicides. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayo-Prieto, S.; Squarzoni, A.; Carro-Huerga, G.; Porteous-Álvarez, A.J.; Gutiérrez, S.; Casquero, P.A. Organic and conventional bean pesticides in development of autochthonous Trichoderma strains. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez-Garay, A.; Astudillo Calderón, S.; Tello Mariscal, M.L.; López, B.P. Effective Control of Neofusicoccum parvum in Grapevines: Combining Trichoderma spp. with Chemical Fungicides. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parraguirre Lezama, C.; Romero-Arenas, O.; Valencia de Ita, M.D.L.A.; Rivera, A.; Sangerman Jarquín, D.M.; Huerta-Lara, M. In vitro study of the compatibility of four species of Trichoderma with three fungicides and their antagonistic activity against Fusarium solani. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Peng, G.; Sun, Y.; Chen, X. Increasing the tolerance of Trichoderma harzianum T-22 to DMI fungicides enables the combined utilization of biological and chemical control strategies against plant diseases. Biol. Control 2024, 192, 105479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widmer, T.L. Compatibility of Trichoderma asperellum isolates to selected soil fungicides. Crop Prot. 2019, 120, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deresa, E.M.; Diriba, T.F. Phytochemicals as alternative fungicides for controlling plant diseases: A comprehensive review of their efficacy, commercial representatives, advantages, challenges for adoption, and possible solutions. Heliyon 2023, 9, e13810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, L.; Wang, Y.; Chen, X.; Zheng, X.; Chen, S.; Li, S.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Y. Exploring the potential of natural products from mangrove rhizosphere bacteria as biopesticides against plant diseases. Plant Dis. 2019, 103, 2925–2932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, H.; Sharma, A.; Roohi; Srivastava, A.K. Biocontrol potential of Bacillus subtilis RH5 against sheath blight of rice caused by Rhizoctonia solani. J. Basic Microbiol. 2020, 60, 268–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakthiyavathi, S.S.K.; Malaisamy, K.; Kamalakannan, M.; Murugesan, V.; Palanisamy, S.R.; Theerthagiri, A.; Rajasekaran, R.; Kasivelu, G. Eco-nanotechnology: Phyto essential oil-based pest control for stored products. Environ. Sci. Nano 2025, 12, 4150–4180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.C.; Viteri, L.O.; Fernandes, P.R.; Carvalho, R.C.; Gonzalez, M.A.; Herrera, O.M.; Osório, P.R.; Mourão, D.S.C.; Araujo, S.H.; Moraes, C.B.; et al. Morinda citrifolia Essential Oil in the Control of Banana Anthracnose: Impacts on Phytotoxicity, Preventive and Curative Effects and Fruit Quality. Microbiol. Res. 2025, 16, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, S.; Yadav, P.K.; Sarhan, A. Botanical fungicides; current status, fungicidal properties and challenges for wide scale adoption: A review. RFNA 2021, 2, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Gómez, S.; Jiménez-García, S.; Campos, V.B.; Ma, L.G.C. Plant Pathology and Management of Plant Diseases. In Plant Diseases—Current Threats and Management Trends; Topolovec-Pintarić, S., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Damascena, J.F.; Viteri, L.O.; Souza, M.H.P.; Aguiar, R.W.; Camara, M.P.; Moura, W.S.; Oliveira, E.E.; Santos, G.R. The Preventive and Curative Potential of Morinda citrifolia Essential Oil for Controlling Anthracnose in Cassava Plants: Fungitoxicity, Phytotoxicity and Target Site. Stresses 2024, 4, 663–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, E.A.J.; da Silva, V.P.; Alves, C.C.F.; Alves, J.M.; Souchie, E.L.; de Almeida Barbosa, L.C. Chemical composition of the essential oil of Psidium guajava leaves and its toxicity against Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Semin. Ciênc. Agrár. 2018, 39, 865–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, B.L.; Ferreira, T.P.d.S.; Dalcin, M.S.; Mourão, D.d.S.C.; Fernandes, P.R.d.S.; Neitzke, T.R.; Oliveira, J.V.d.A.; Dias, T.; Jumbo, L.O.V.; de Oliveira, E.E.; et al. Lippia sidoides Cham. Compounds Induce Biochemical Defense Mechanisms Against Curvularia lunata sp. in Maize Plants. J 2025, 8, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourão, D.d.S.C.; Dias, B.L.; Dalcin, M.S.; Viteri, L.O.; Gonzales, M.A.; Fernandes, P.R.; Silva, V.B.; Costa, M.A.; González, M.J.; Amaral, A.G. Effect of Xylopia frutescens Essential Oil on the Activation of Defense Mechanisms Against Phytopathogenic Fungi. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahraoui, E.M. Essential Oils: Antifungal activity and study methods. Rev. Mar. Sci. Agro. Vet. 2025, 6, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estevam, E.; Silva, E.; Miranda, M.; Alves, J.; Pereira, P.; Silva, F.; Esperandim, V.; Martins, C.; Ambrosio, M.; Tófoli, D. Avaliação das atividades antibacteriana, tripanocida e citotóxica do extrato hidroalcóolico das raízes de Tradescantia sillamontana Matuda (Veludo Branco)(Commelinaceae). Rev. Bras. Plants Med. 2016, 18, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamokou, J.D.D.; Mbaveng, A.T.; Kuete, V. Chapter 8—Antimicrobial Activities of African Medicinal Spices and Vegetables. In Medicinal Spices and Vegetables from Africa; Kuete, V., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 207–237. [Google Scholar]

- Lobão, A.Q.; de Carvalho Lopes, J.; de Mello-Silva, R. Check-list das Annonaceae do estado do Mato Grosso do Sul, Brasil. Iheringia Sér. Bot. 2018, 73, 123–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Moraes, Â.A.B.; Cascaes, M.M.; do Nascimento, L.D.; de Jesus Pereira Franco, C.; Ferreira, O.O.; Anjos, T.O.d.; Karakoti, H.; Kumar, R.; da Silva Souza-Filho, A.P.; de Oliveira, M.S. Chemical evaluation, phytotoxic potential, and in silico study of essential oils from leaves of Guatteria schomburgkiana Mart. and Xylopia frutescens Aubl.(Annonaceae) from the Brazilian Amazon. Molecules 2023, 28, 2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Karkouri, J.; Bouhrim, M.; Al Kamaly, O.M.; Mechchate, H.; Kchibale, A.; Adadi, I.; Amine, S.; Alaoui Ismaili, S.; Zair, T. Chemical Composition, Antibacterial and Antifungal Activity of the Essential Oil from Cistus ladanifer L. Plants 2021, 10, 2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Menezes Filho, A.C.P.; de Sousa, W.C.; Silva, J.L.; da Cruz, R.M.; da Silva, A.P.; de Souza Castro, C.F. Chemical profile and antifungal activity of essential oil from the flower of Bauhinia rufa (Bong.) Steud. Braz. J. Sci. 2022, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghani Bidgoli, R. Chemical composition of essential oil and antifungal activity of Artemisia persica Boiss. from Iran. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 58, 1313–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, A.; Maia, T.; Soares, T.; Menezes, L.; Scher, R.; Costa, E.; Cavalcanti, S.; La Corte, R. Repellency and larvicidal activity of essential oils from Xylopia laevigata, Xylopia frutescens, Lippia pedunculosa, and their individual compounds against Aedes aegypti Linnaeus. Neotrop. Entomol. 2017, 46, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, T.B.; Costa, C.O.D.S.; Galvão, A.F.; Bomfim, L.M.; Rodrigues, A.C.B.d.C.; Mota, M.C.; Dantas, A.A.; Dos Santos, T.R.; Soares, M.B.; Bezerra, D.P. Cytotoxic potential of selected medicinal plants in northeast Brazil. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2016, 16, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraz, R.P.; Cardoso, G.M.; da Silva, T.B.; Fontes, J.E.d.N.; Prata, A.P.d.N.; Carvalho, A.A.; Moraes, M.O.; Pessoa, C.; Costa, E.V.; Bezerra, D.P. Antitumour properties of the leaf essential oil of Xylopia frutescens Aubl.(Annonaceae). Food Chem. 2013, 141, 196–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cascaes, M.M.; Marques da Silva, S.H.; de Oliveira, M.S.; Cruz, J.N.; de Moraes, Â.A.B.; do Nascimento, L.D.; Ferreira, O.O.; Guilhon, G.M.S.P.; Andrade, E.H.d.A. Exploring the chemical composition, in vitro and in silico study of the anticandidal properties of annonaceae species essential oils from the Amazon. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0289991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakri, N.M.; Salleh, W.M.N.H.W.; Khamis, S.; Mohamad Ali, N.A.; Nadri, M.H. Composition of the essential oils of three Malaysian Xylopia species (Annonaceae). Z. Naturforsch. B 2020, 75, 479–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almas, I.; Innocent, E.; Machumi, F.; Kisinza, W. Effect of Geographical location on yield and chemical composition of essential oils from three Eucalyptus species growing in Tanzania. Asian J. Tradit. Med. 2018, 14, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- da Cruz, E.d.N.S.; Peixoto, L.d.S.; da Costa, J.S.; Mourão, R.H.V.; do Nascimento, W.M.O.; Maia, J.G.S.; Setzer, W.N.; da Silva, J.K.; Figueiredo, P.L.B. Seasonal variability of a caryophyllane chemotype essential oil of Eugenia patrisii Vahl occurring in the Brazilian Amazon. Molecules 2022, 27, 2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascaes, M.M.; De Moraes, Â.A.B.; Cruz, J.N.; Franco, C.d.J.P.; E Silva, R.C.; Nascimento, L.D.d.; Ferreira, O.O.; Anjos, T.O.d.; de Oliveira, M.S.; Guilhon, G.M.S.P. Phytochemical profile, antioxidant potential and toxicity evaluation of the essential oils from Duguetia and Xylopia species (Annonaceae) from the Brazilian Amazon. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camara, M.B.; Lima, A.S.; Jumbo, L.O.V.; Tavares, C.P.; Mendonça, C.d.J.S.; Monteiro, O.S.; Araújo, S.H.C.; Oliveira, E.E.d.; Lima Neto, J.S.; Maia, J.G.S. Seasonal and circadian evaluation of the Pectis brevipedunculata essential oil and Its acaricidal activity against Rhipicephalus microplus (Acari: Ixodidae). J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2023, 34, 1020–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, Y.J.; de Brito Machado, D.; de Queiroz, G.A.; Guimarães, E.F.; e Defaveri, A.C.A.; de Lima Moreira, D. Chemical composition of the essential oils of circadian rhythm and of different vegetative parts from Piper mollicomum Kunth-A medicinal plant from Brazil. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2020, 92, 104116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, N.; Kefi, S.; Tabben, O.; Ayed, A.; Jallouli, S.; Feres, N.; Hammami, M.; Khammassi, S.; Hrigua, I.; Nefisi, S. Variation in chemical composition of Eucalyptus globulus essential oil under phenological stages and evidence synergism with antimicrobial standards. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2018, 124, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radušienė, J.; Karpavičienė, B.; Marksa, M.; Ivanauskas, L.; Raudonė, L. Distribution patterns of essential oil terpenes in native and invasive Solidago species and their comparative assessment. Plants 2022, 11, 1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasconcelos, P.G.S.; Lee, K.M.; Abuna, G.F.; Costa, E.M.M.B.; Murata, R.M. Monoterpene antifungal activities: Evaluating geraniol, citronellal, and Linalool on Candida biofilm, host inflammatory responses, and structure–activity relationships. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1394053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skamnaki, V.T.; Peumans, W.J.; Kantsadi, A.L.; Cubeta, M.A.; Plas, K.; Pakala, S.; Zographos, S.E.; Smagghe, G.; Nierman, W.C.; Van Damme, E.J. Structural analysis of the Rhizoctonia solani agglutinin reveals a domain-swapping dimeric assembly. FEBS J. 2013, 280, 1750–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tegang, A.S.; Beumo, T.M.N.; Dongmo, P.M.J.; Ngoune, L.T. Essential oil of Xylopia aethiopica from Cameroon: Chemical composition, antiradical and in vitro antifungal activity against some mycotoxigenic fungi. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2018, 30, 466–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndoye, S.F.; Tine, Y.; Seck, I.; Ba, L.A.; Ka, S.; Ciss, I.; Ba, A.; Sokhna, S.; Ndao, M.; Gueye, R.S. Chemical constituents and antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of essential oil from dried seeds of Xylopia aethiopica. Biochem. Res. Int. 2024, 2024, 3923479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xavier, M.N.; Alves, J.M.; Carneiro, N.S.; Souchie, E.L.; Silva, E.A.J.; Martins, C.H.G.; Ambrósio, M.A.L.; Egea, M.B.; Alves, C.C.F.; Miranda, M.L.D. Composição química do óleo essencial de Cardiopetalum calophyllum Schltdl. (Annonaceae) e suas atividades antioxidante, antibacteriana e antifúngica. Rev. Virtual Quim. 2016, 8, 1433–1448. [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca, A.C.C.; Rotili, E.; Ferreira, T.; Mourão, D.; Dias, B.; Oliveira, G.; Santos, G. Potencial do óleo essencial de noni no controle preventivo e curativo da antracnose da mangueira. J. Biotechnol. Biodivers 2019, 7, 356–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahizan, N.A.; Yang, S.-K.; Moo, C.-L.; Song, A.A.-L.; Chong, C.-M.; Chong, C.-W.; Abushelaibi, A.; Lim, S.-H.E.; Lai, K.-S. Terpene derivatives as a potential agent against antimicrobial resistance (AMR) pathogens. Molecules 2019, 24, 2631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd-ElGawad, A.M.; El Gendy, A.E.-N.G.; Assaeed, A.M.; Al-Rowaily, S.L.; Alharthi, A.S.; Mohamed, T.A.; Nassar, M.I.; Dewir, Y.H.; Elshamy, A.I. Phytotoxic effects of plant essential oils: A systematic review and structure-activity relationship based on chemometric analyses. Plants 2020, 10, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fialho, R.d.O.; Papa, M.d.F.S.; Pereira, D.A.d.S. Efeito fungitóxico de óleos essenciais sobre Phakopsora euvitis, agente causal da ferrugem da videira. Arq. Inst. Biol. 2015, 82, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, R.C.d.S.; Amaral, B.d.O.; Lima, N.K.; Lopes, A.d.S.; Carmo, D.F.d.M.; Guesdon, I.R.; Bardales-Lozano, R.M.; Schwartz, G.; Dionisio, L.F.; Ávila, M.d.S. Phytotoxicity of Piper marginatum Jacq. essential oil on detached leaves and post-emergence of plants. Rev. Bras. Eng. Agríc. Ambient. 2024, 29, e284276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiva-Mora, M.; Bustillos, D.; Arteaga, C.; Hidalgo, K.; Guevara-Freire, D.; López-Hernández, O.; Saa, L.R.; Padilla, P.S.; Bustillos, A. Antifungal Mechanisms of Plant Essential Oils: A Comprehensive Literature Review for Biofungicide Development. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourão, D.D.S.C.; De Souza, M.R.; Dos Reis, J.V.L.; Ferreira, T.P.D.S.; Osorio, P.R.A.e.; Dos Santos, E.R.; Da Silva, D.B.; Tschoeke, P.H.; Campos, F.S.; Dos Santos, G.R. Fungistatic activity of essential oils for the control of bipolaris leaf spot in maize. J. Med. Plants Res. 2019, 13, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.A.; Wanderley-Teixeira, V.; Navarro, D.M.; Dutra, K.A.; Cruz, G.S.; Teixeira, Á.A.; Oliveira, J.V.; Milet-Pinheiro, P. Oviposition behaviour and electrophysiological responses of Alabama argillacea (Hübner, 1823) (Lepidoptera: Erebidae) to essential oils and chemical compounds. Austral Entomol. 2021, 60, 390–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Li, S.; Wei, S.; Sun, W. Strategies to manage rice sheath blight: Lessons from interactions between rice and Rhizoctonia solani. Rice 2021, 14, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, R.; He, L.; He, J.; Qin, P.; Wang, Y.; Deng, Q.; Yang, X.; Li, S.; Wang, S.; Wang, W. Comprehensive analysis of microRNA-Seq and target mRNAs of rice sheath blight pathogen provides new insights into pathogenic regulatory mechanisms. DNA Res. 2016, 23, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Zhao, S.-L.; Liu, K.; Sun, Y.-B.; Ni, Z.-B.; Zhang, G.-Y.; Tang, H.-S.; Zhu, J.-W.; Wan, B.-J.; Sun, H.-Q. Comparison of leaf transcriptome in response to Rhizoctonia solani infection between resistant and susceptible rice cultivars. BMC Genom. 2020, 21, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mousa, W.K.; Raizada, M.N. The diversity of anti-microbial secondary metabolites produced by fungal endophytes: An interdisciplinary perspective. Front. Microbiol. 2013, 4, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Kosma, D.K.; Lü, S. Functional role of long-chain acyl-CoA synthetases in plant development and stress responses. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 640996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, A.; Mubeen, M.; Iftikhar, Y.; Shakeel, Q.; Imran Arshad, H.M.; Carmen Zuñiga Romano, M.d.; Hussain, S. Rice Sheath Blight: A Comprehensive Review on the Disease and Recent Management Strategies. Sarhad J. Agric. 2023, 39, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvind, M.; Prashanthi, S. Comparative analysis of two predominant methods of rice sheath blight inoculation. J. Crop Weed 2023, 19, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Akhtar, M.N.; Kumar, T. Standardization of inoculation techniques for sheath blight of rice caused by Rhizoctonia solani (Kuhn). Bangladesh J. Bot. 2019, 48, 1107–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doni, F.; Isahak, A.; Fathurrahman, F.; Yusoff, W.M.W. Rice plants’ resistance to sheath blight infection is increased by the synergistic effects of Trichoderma inoculation with SRI management. Agronomy 2023, 13, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurhayati, Y.; Suryanti, S.; Wibowo, A. In vitro evaluation of Trichoderma asperellum isolate UGM-LHAF against Rhizoctonia solani causing sheath blight disease of rice. JPTI 2021, 25, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seixas, P.T.L.; Castro, H.G.; Cardoso, D.P.; Junior, A.F.C.; do Nascimento, I.R. Bioactivity of essential oils on the fungus Didymella bryoniae of the cucumber culture. Appl. Res. Agrotechnology 2012, 5, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, L.G.d.L.; Cardoso, M.d.G.; Zacaroni, L.M.; Lima, R.K.d.; Pimentel, F.A.; Morais, A.R.d. Influence of light and temperature on the oxidation of the essential oil of lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus (DC) Stapf). Quim. Nova 2008, 31, 1476–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio, P.R.A.; Leão, E.U.; Veloso, R.A.; Mourão, D.d.S.C.; Santos, G.R.d. Essential oils for alternative teak rust control. Floresta Ambient. 2018, 25, e20160391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krutmuang, P.; Rajula, J.; Pittarate, S.; Chatima, C.; Thungrabeab, M.; Mekchay, S.; Senthil-Nathan, S. The inhibitory action of plant extracts on the mycelial growth of Ascosphaera apis, the causative agent of chalkbrood disease in Honey bee. Toxicol. Rep. 2022, 9, 713–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, A.B.L.; Martins, R.L.; de Menezes Rabelo, É.; de Matos, J.L.; Santos, L.L.; Brandão, L.B.; Chaves, R.d.S.B.; da Costa, A.L.P.; Faustino, C.G.; da Cunha Sá, D.M. In silico and in vivo study of adulticidal activity from Ayapana triplinervis essential oils nano-emulsion against Aedes aegypti. Arab. J. Chem. 2022, 15, 104033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, A.S.; de Oliveira Farias, J.C.R.; da Silva Nascimento, J.; Costa, E.C.S.; dos Santos, F.H.G.; de Araújo, H.D.A.; da Silva, N.H.; Pereira, E.C.; Martins, M.C.; Falcão, E.P.S. Larvicidal activity and docking study of Ramalina complanata and Cladonia verticillaris extracts and secondary metabolites against Aedes aegypti. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2023, 195, 116425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persaud, R.; Saravanakumar, D.; Persaud, M. Identification of resistant cultivars for sheath blight and use of AMMI models to understand genotype and environment interactions. Plant Dis. 2019, 103, 2204–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, G.M.; Huey, R.; Lindstrom, W.; Sanner, M.F.; Belew, R.K.; Goodsell, D.S.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 2009, 30, 2785–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Y.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, B.; Luo, Y.; Tian, J.; Wang, Y.; Ju, X.; Wu, J.; Li, Y. Integrating Network Pharmacology, Molecular Docking, and Experimental Validation to Investigate the Mechanism of (−)-Guaiol Against Lung Adenocarcinoma. Med. Sci. Monit. 2022, 28, e937131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dequech, S.; Ribeiro, L.d.P.; Sausen, C.; Egewarth, R.; Kruse, N. Fitotoxicidade causada por inseticidas botânicos em feijão-de-vagem (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) cultivado em estufa plástica. Rev. Fac. Zootec. Vet. Agron. 2008, 15, 71–80. [Google Scholar]

- Freitas, S.; Moreira, J.; Freitas, I.; Freitas Júnior, S.; Amaral Júnior, A.d.; Silva, V. Fitotoxicidade de herbicidas a diferentes cultivares de milho-pipoca. Planta Daninha 2009, 27, 1095–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cogliatti, M.; Juan, V.; Bongiorno, F.; Dalla Valle, H.; Rogers, W. Control of grassy weeds in annual canarygrass. Crop Prot. 2011, 30, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, G.R.d.; Café-Filho, A.C.; Leão, F.F.; César, M.; Fernandes, L.E. Progresso do crestamento gomoso e perdas na cultura da melancia. Hortic. Bras. 2005, 23, 228–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, R.; Williams, R.; Sinclair, J. Cercospora leaf spot of cowpea: Models for estimating yield loss. Phytopathology 1976, 66, 384–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SAS. SAS/STAT User’s Guide: GLM-VARCOMP; SAS Institute Incorporated: Cary, NC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

| CN | Constituents | RT | RIC | RIR | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2,5-cyclohexadiene-1-methanol | 3890 | 3860 | 3925 | 0.29 |

| 2 | α-pinene | 4969 | 4915 | 5105 | 7.87 |

| 3 | Thuja-2,4(10)-diene | 5430 | 5380 | 5525 | 2.05 |

| 4 | β-pinene | 5948 | 5890 | 6070 | 6.57 |

| 5 | o-Cymol | 7160 | 7110 | 7210 | 2.06 |

| 6 | Eucalyptol | 7305 | 7210 | 7415 | 2.53 |

| 7 | Comphene | 7475 | 7415 | 7547.5 | 1.62 |

| 8 | Canfenilone | 8690 | 8640 | 8755 | 0.39 |

| 9 | Dihydrocarveol | 8855 | 8785 | 8880 | 0.51 |

| 10 | α-campholenal | 8900 | 8880 | 8960 | 0.38 |

| 11 | α-fenchocamphorona | 9261 | 9230 | 9300 | 0.39 |

| 12 | Phenylic alcohol | 9544 | 9490 | 9595 | 0.61 |

| 13 | α-fluorohenaldehyde | 9862 | 9815 | 9925 | 1.34 |

| 14 | Nopinone | 10,126 | 10,065 | 10,170 | 3.74 |

| 15 | Trans-pinocarveol | 10,219 | 10,170 | 10,275 | 11.49 |

| 16 | Cis-verbenol | 10,299 | 10,275 | 10,360 | 1.21 |

| 17 | Trans-verbenol | 10,401 | 10,360 | 10,460 | 3.07 |

| 18 | Mentha-1,5-dieno-8-ol | 10,506 | 10,460 | 10,610 | 1.23 |

| 19 | 2-methylene-6,6-dimethyl-bicyclo [3.2.0] heptane-3-ol | 10,727 | 10,670 | 10,760 | 0.69 |

| 20 | Pinocamphone | 10,785 | 10,760 | 10,805 | 0.46 |

| 21 | Pinocarvone | 10,845 | 10,805 | 10,900 | 6.46 |

| 22 | 3,5-Dimethyl-5-ethyl-. DELTA [2]-pyrazoline | 10,915 | 10,900 | 10,940 | 0.45 |

| 23 | Borneol | 10,980 | 10,940 | 11,000 | 1.32 |

| 24 | p-1,5-Menthodienol-8 | 11,028 | 11,000 | 11,130 | 2.61 |

| 25 | (2,2,6-trimethyl-bicyclo[4.1.0]hept-1-yl)-methanol | 11,221 | 11,130 | 11,255 | 0.5 |

| 26 | 4-terpineol | 11,295 | 11,255 | 11,345 | 0.95 |

| 27 | Mirta | 11,394 | 11,345 | 11,485 | 0.76 |

| 28 | P-cymen-8-ol | 11,557 | 11,490 | 11,640 | 1.37 |

| 29 | α-TERPINEOL | 11,687 | 11,640 | 11,725 | 0.78 |

| 30 | Myrtenal | 11,777 | 11,725 | 11,810 | 9.99 |

| 31 | Myrtenol | 11,839 | 11,810 | 11,980 | 6.68 |

| 32 | Verbenone | 12,139 | 12,085 | 12,280 | 7.16 |

| 33 | Cis-carveol | 12,475 | 12,425 | 12,560 | 1.03 |

| 34 | Cyclooctene, 3-(1-methylethenyl) | 13,940 | 13,895 | 14,015 | 0.39 |

| 35 | Perillyl alcohol | 14,641 | 14,600 | 16,685 | 0.32 |

| 36 | Cycloactive | 16,370.5 | 16,332.5 | 16,417.5 | 0.7 |

| 37 | Copaene | 16,625 | 16,580 | 16,685 | 0.43 |

| 38 | Thujpsadiene | 17,380 | 17,335 | 17,430 | 0.29 |

| 39 | 2,3,3-Trimethyl-2-(3-methyl-buta-1,3-dienyl)-cyclohexanone | 20,978 | 20,930 | 21,020 | 0.44 |

| 40 | 1H-cycloprop[e]azulen-7-ol, decahydro-1,1,7-trimethyl-4-methylene-, [1ar-(1a.α,4a.α,7 β,7a. β,7b.α)] | 21,577 | 21,470 | 21,655 | 4.33 |

| 41 | Caryophyllene oxide | 21,682 | 21,655 | 21,765 | 0.7 |

| 42 | Spiro[4.5]dec-6-en-8-one, 1,7-dimethyl-4-(1-methylethyl) | 22,191 | 22,135 | 22,225 | 0.28 |

| 43 | 4,8,8-trimethyl-2-methylene-bicyclo[5.2.0]nonane- | 22,299 | 22,225 | 22,350 | 0.43 |

| 44 | Isospathulenol | 22,761 | 22,705 | 22,860 | 0.75 |

| 45 | Widdrol | 23,290 | 23,235 | 23,345 | 0.92 |

| 46 | (4,6,8,9-tetramethyl-3-oxabicyclo[3.3.1]non-6-eno-1-yl)methyl acetate | 23,390 | 23,345 | 23,475 | 0.72 |

| 47 | Mustakone | 23,831 | 23,770 | 23,880 | 0.74 |

| Total | - | 600,460 | 598,143 | 605,510 | 100 |

| Treatment (mg/mL) | Sclerotia Germination Over Time (mm ±SE) | IGS a (%) | Mycelial Growth Over Time (mm ± SE) | IGM b (%) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 10 | |||

| Control | 78.2 ± 9.5 | 90 ± 0 | 90 ± 0 | 90 ± 0 | 90 ± 0 | - | 42.6 ± 1.9 | 90 ± 0 | 90 ± 0 | 90 ± 0 | 90 ± 0 | - |

| Methyl thiophanate (20) | 12 ± 0.4 | 13.5 ± 0.6 | 13.5 ± 0.6 | 13.5 ± 0.6 | 13.5 ± 0.6 | 85 | 8.1 ± 3.4 | 18 ± 3.8 | 18.3 ± 6.3 | 18.3 ± 6.3 | 18.3 ± 6.3 | 79.95 |

| 5.0 | - | 47.7 ± 8.2 | 90 ± 0 | 90 ± 0 | 90 ± 0 | 29.4 | 18.6 ± 1.7 | 90 ± 0 | 90 ± 0 | 90 ± 0 | 90 ± 0 | 11.3 |

| 7.5 | - | - | - | - | 30 ± 25 | 93.3 | 16.2 ± 0.4 | 86.1 ± 3.2 | 90 ± 0 | 90 ± 0 | 90 ± 0 | 13.3 |

| 10.0 | - | - | - | - | - | 100 | 12 ± 0.8 | 76.4 ± 0.8 | 90 ± 0 | 90 ± 0 | 90 ± 0 | 17.4 |

| 25.0 | - | - | - | - | - | 100 | - | - | 23 ± 10.6 | 54.2 ± 22.5 | 60 ± 24.5 | 70.8 |

| 50.0 | - | - | - | - | - | 100 | - | - | 7.3 ± 6 | 26.3 ± 21.5 | 30 ± 24.5 | 86.7 |

| Specie | Molecule | Bond Energy (Kcal/mol) | Ki (nM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Xylopia frutescens | Trans-pinocarveol | −5.36 | 117.71 |

| Myrtenal | −5.01 | 213.86 |

| Model | Cultivate | Target | Exposure | Estimated Parameters (±SE) | df Error | F | P | R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | y0 | ||||||||

| f = y0 + ax | BRS Esmeralda | sclerotia | preventive | −5.40 ± 1.12 a | 234.50 ± 29.13 a | 4 | 23.18 | 0.0171 | 0.88 |

| curative | −4.95 ± 0.75 a | 255.25 ± 19.68 a | 4 | 42.67 | 0.0073 | 0.93 | |||

| mycelium | preventive | −6.81 ± 0.80 a | 268.43 ± 20.95 a | 4 | 71.36 | 0.0035 | 0.94 | ||

| curative | −6.66 ± 0.38 a | 291.68 ± 10.06 a | 4 | 296.02 | 0.0004 | 0.99 | |||

| BRS Cambará | sclerotia | preventive | −6.77 ± 0.43 a | 288.37 ± 1.24 a | 4 | 245.07 | 0.0006 | 0.98 | |

| curative | −9.00 ± 0.51 b | 394.38 ± 13.45 b | 4 | 301.86 | 0.0004 | 0.99 | |||

| mycelium | preventive | −6.81 ± 0.80 a | 268.43 ± 20.95 a | 4 | 71.36 | 0.0035 | 0.96 | ||

| curative | −7.07 ± 0.34 a | 306.87 ± 9.02 b | 4 | 414.96 | 0.0003 | 0.99 | |||

| BRS Pampeira | sclerotia | preventive | −6.56 ± 1.02 a | 263.31 ± 26.69 a | 4 | 40.79 | 0.0078 | 0.93 | |

| curative | −5.30 ± 0.71 a | 252.50 ± 18.53 a | 4 | 55.16 | 0.0051 | 0.95 | |||

| mycelium | preventive | −2.72 ± 0.21 a | 139.13 ± 5.63 a | 4 | 157.71 | 0.0011 | 0.98 | ||

| curative | −4.42 ± 0.40 b | 215.00 ± 10.60 b | 4 | 117.63 | 0.0017 | 0.98 | |||

| BRS Catiana | sclerotia | preventive | −3.25 ± 0.42 a | 175.00 ± 11.04 a | 4 | 58.41 | 0.0047 | 0.95 | |

| curative | −6.73 ± 0.82 b | 308.19 ± 21.33 b | 4 | 67.31 | 0.0038 | 0.95 | |||

| mycelium | preventive | −5.02 ± 0.65 a | 219.50 ± 17.06 a | 4 | 58.52 | 0.0046 | 0.95 | ||

| curative | −4.97 ± 0.94 a | 250.13 ± 24.46 a | 4 | 192.23 | 0.0007 | 0.90 | |||

| Treatments (mg/mL) | Mycelial Growth Over Time (mm ± SE) | MGI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 10 | (%) | |

| Control | 55.8 ± 1.06 | 90 ± 0 | 90 ± 0 | 90 ± 0 | 90 ± 0 | 0.00 |

| Methyl thiophanate | 17.73 ± 1.05 | 17.73 ± 0.94 | 17.73 ± 0.94 | 17.73 ± 0.94 | 17.73 ± 0.94 | 77.88 |

| 15.0 | 53.32 ± 2.19 | 90 ± 00 | 90 ± 00 | 90 ± 00 | 90 ± 00 | 1 |

| 20.0 | 49.23 ± 1.20 | 90 ± 00 | 90 ± 00 | 90 ± 00 | 90 ± 00 | 2 |

| 25.0 | 46.61 ± 1.26 | 90 ± 00 | 90 ± 00 | 90 ± 00 | 90 ± 00 | 3 |

| 30.0 | 46.61 ± 1.26 | 90 ± 00 | 90 ± 00 | 90 ± 00 | 90 ± 00 | 3 |

| 35.0 | 39.97 ± 1.22 | 90 ± 00 | 90 ± 00 | 90 ± 00 | 90 ± 00 | 6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fernandes, P.R.S.; Mourão, D.d.S.C.; Viteri, L.O.; Silva Júnior, A.A.; Bilal, M.; Kanwal, A.; Herrera, O.M.; Gonzalez, M.A.; Souza, L.A.; Amaral, A.G.; et al. Essential Oil of Xylopia frutescens Controls Rice Sheath Blight Without Harming the Beneficial Biocontrol Agent Trichoderma asperellum. Plants 2026, 15, 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010031

Fernandes PRS, Mourão DdSC, Viteri LO, Silva Júnior AA, Bilal M, Kanwal A, Herrera OM, Gonzalez MA, Souza LA, Amaral AG, et al. Essential Oil of Xylopia frutescens Controls Rice Sheath Blight Without Harming the Beneficial Biocontrol Agent Trichoderma asperellum. Plants. 2026; 15(1):31. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010031

Chicago/Turabian StyleFernandes, Paulo Ricardo S., Dalmarcia de Souza C. Mourão, Luís O. Viteri, Adauto A. Silva Júnior, Muhammad Bilal, Anila Kanwal, Osmany M. Herrera, Manuel A. Gonzalez, Leandro A. Souza, Ana G. Amaral, and et al. 2026. "Essential Oil of Xylopia frutescens Controls Rice Sheath Blight Without Harming the Beneficial Biocontrol Agent Trichoderma asperellum" Plants 15, no. 1: 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010031

APA StyleFernandes, P. R. S., Mourão, D. d. S. C., Viteri, L. O., Silva Júnior, A. A., Bilal, M., Kanwal, A., Herrera, O. M., Gonzalez, M. A., Souza, L. A., Amaral, A. G., Rocha, T. C. d., Câmara, M. P. S., Pimenta, R. S., Giongo, M. V., Oliveira, E. E., Aguiar, R. W. S., & Santos, G. R. (2026). Essential Oil of Xylopia frutescens Controls Rice Sheath Blight Without Harming the Beneficial Biocontrol Agent Trichoderma asperellum. Plants, 15(1), 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010031