Applying Flora Composition and Leaf Physiognomy to Reconstruct the Paleocommunity, Palaeoclimate, and Paleoenvironment of the Jehol Biota in Jilin, China

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Taxonomic Composition of Baishan Flora

2.1.1. Taxonomic Composition

2.1.2. Characteristics of the Baishan Flora

2.2. Paleoecology of the Flora

2.2.1. Taphonomic Analysis

2.2.2. Paleoecological Analysis of Plant Fossil Taxa

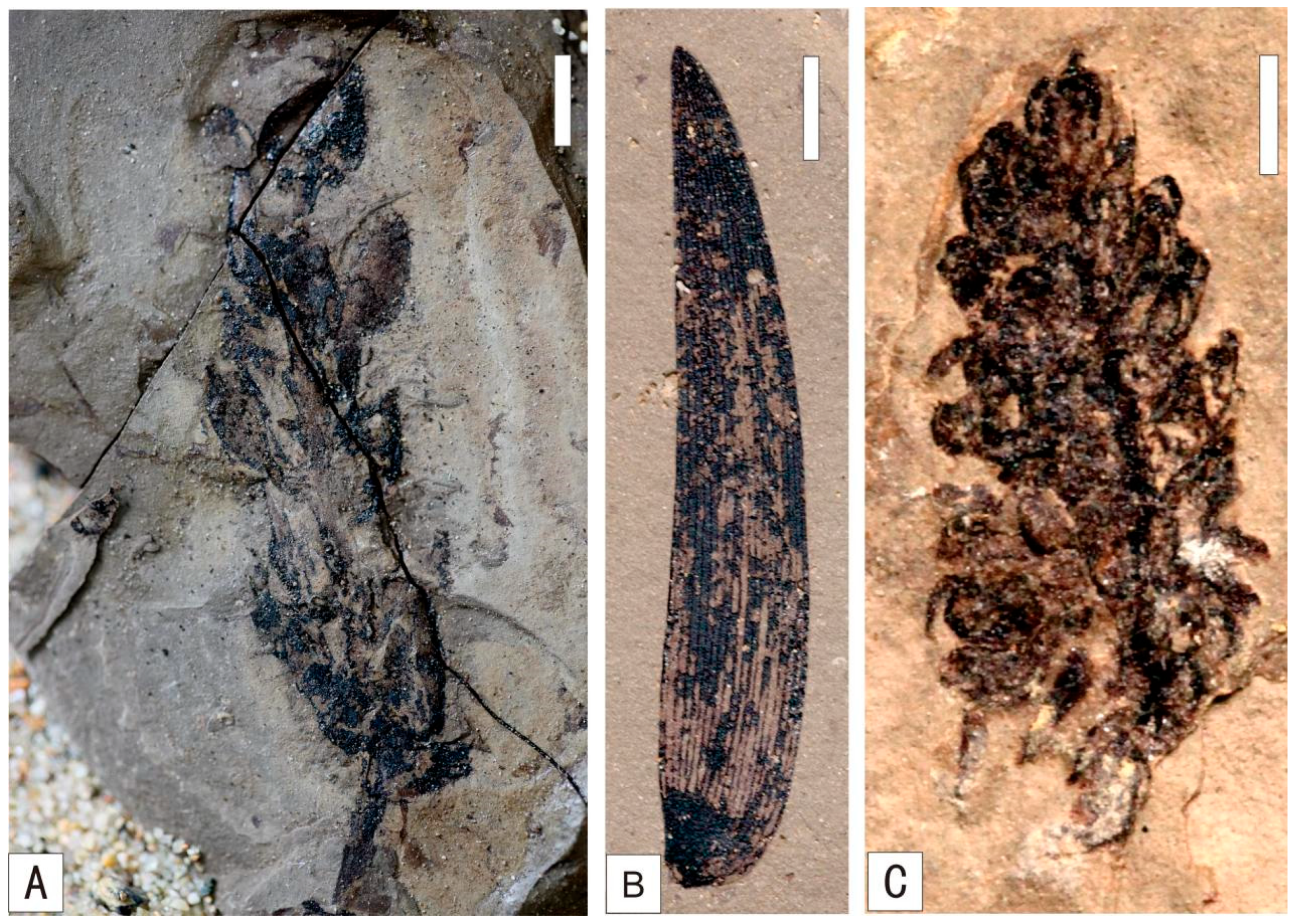

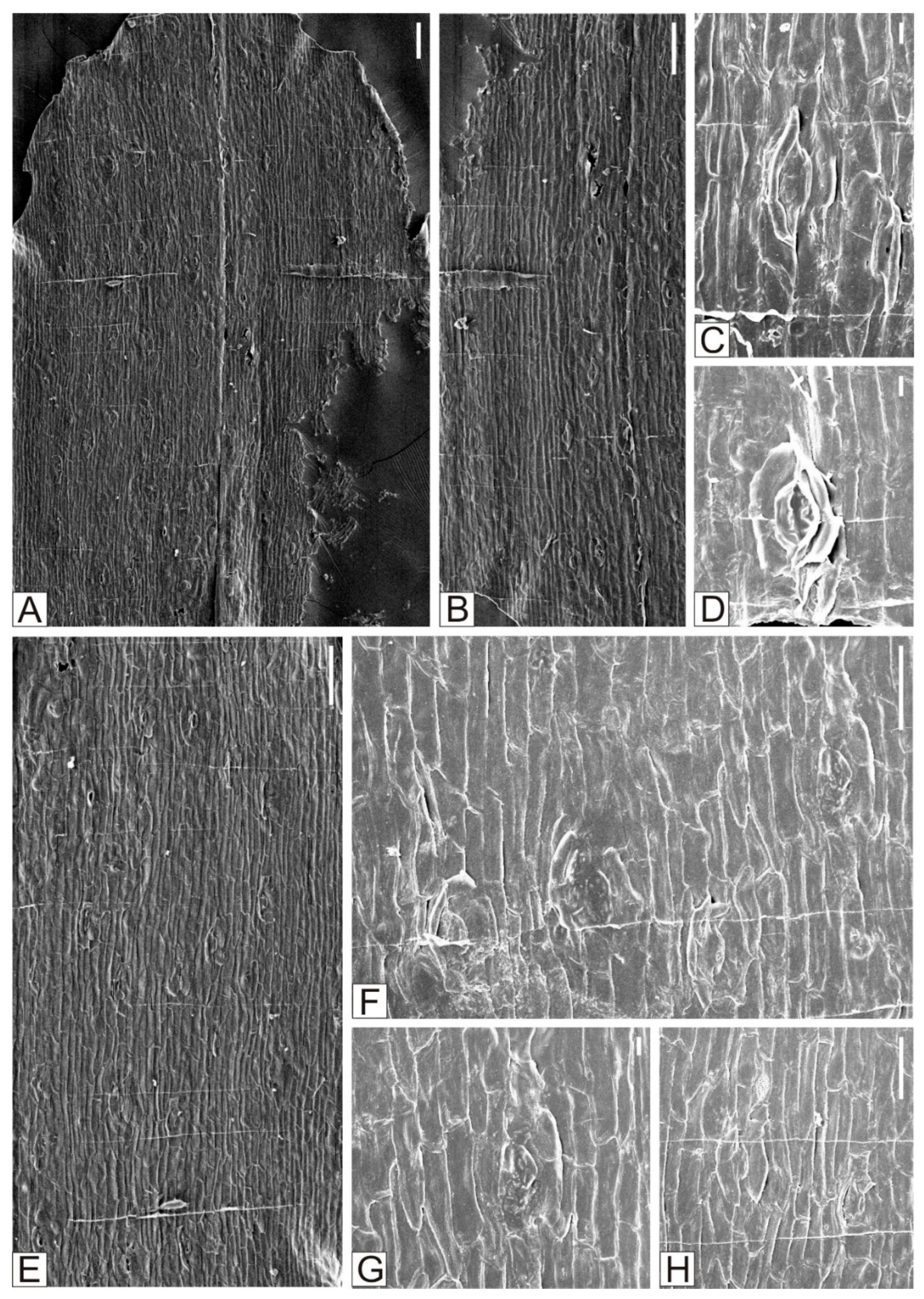

- Sphenopsida

- 2.

- Filicopsida

- 3.

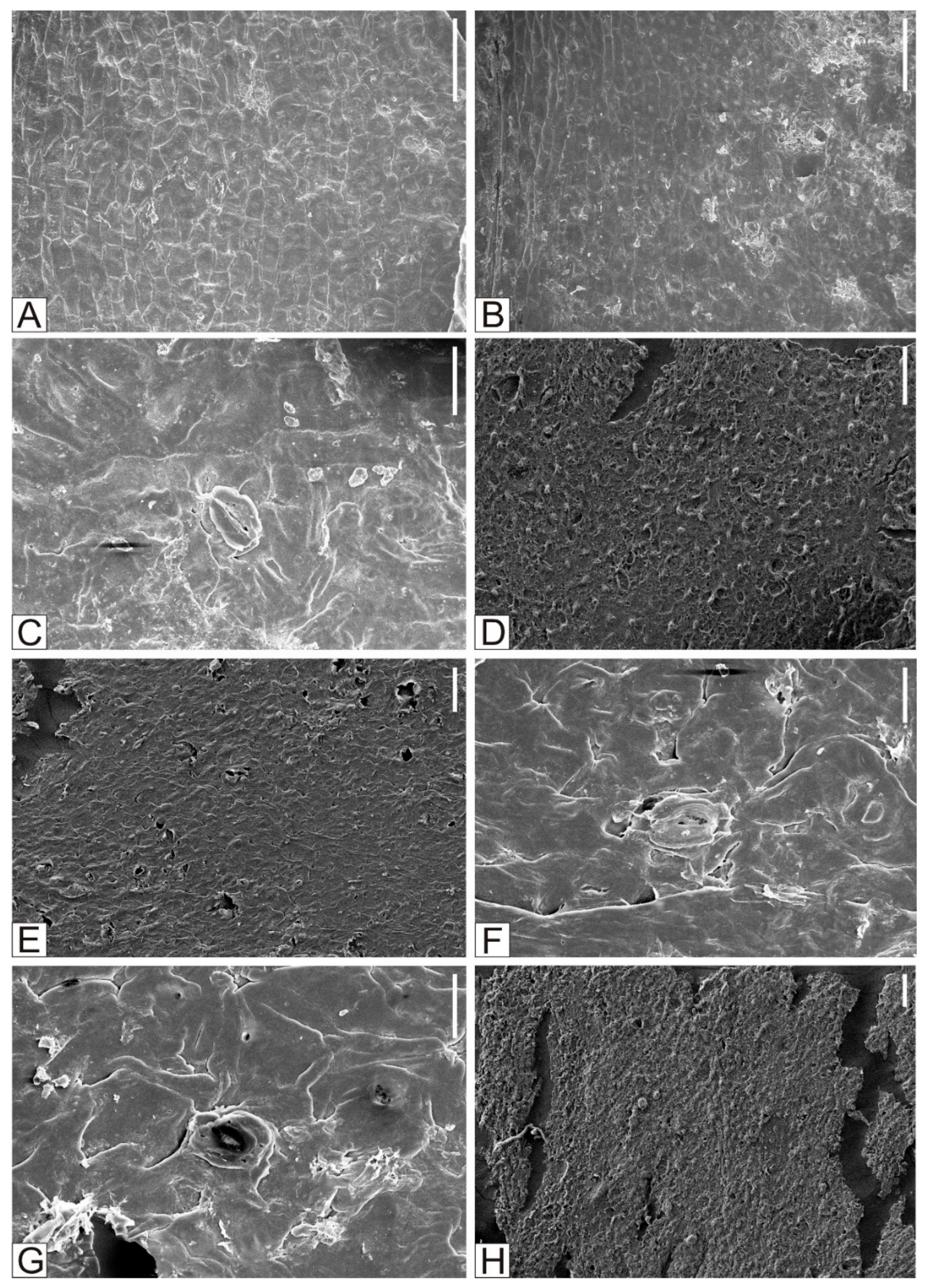

- Cycadopsida

- 4.

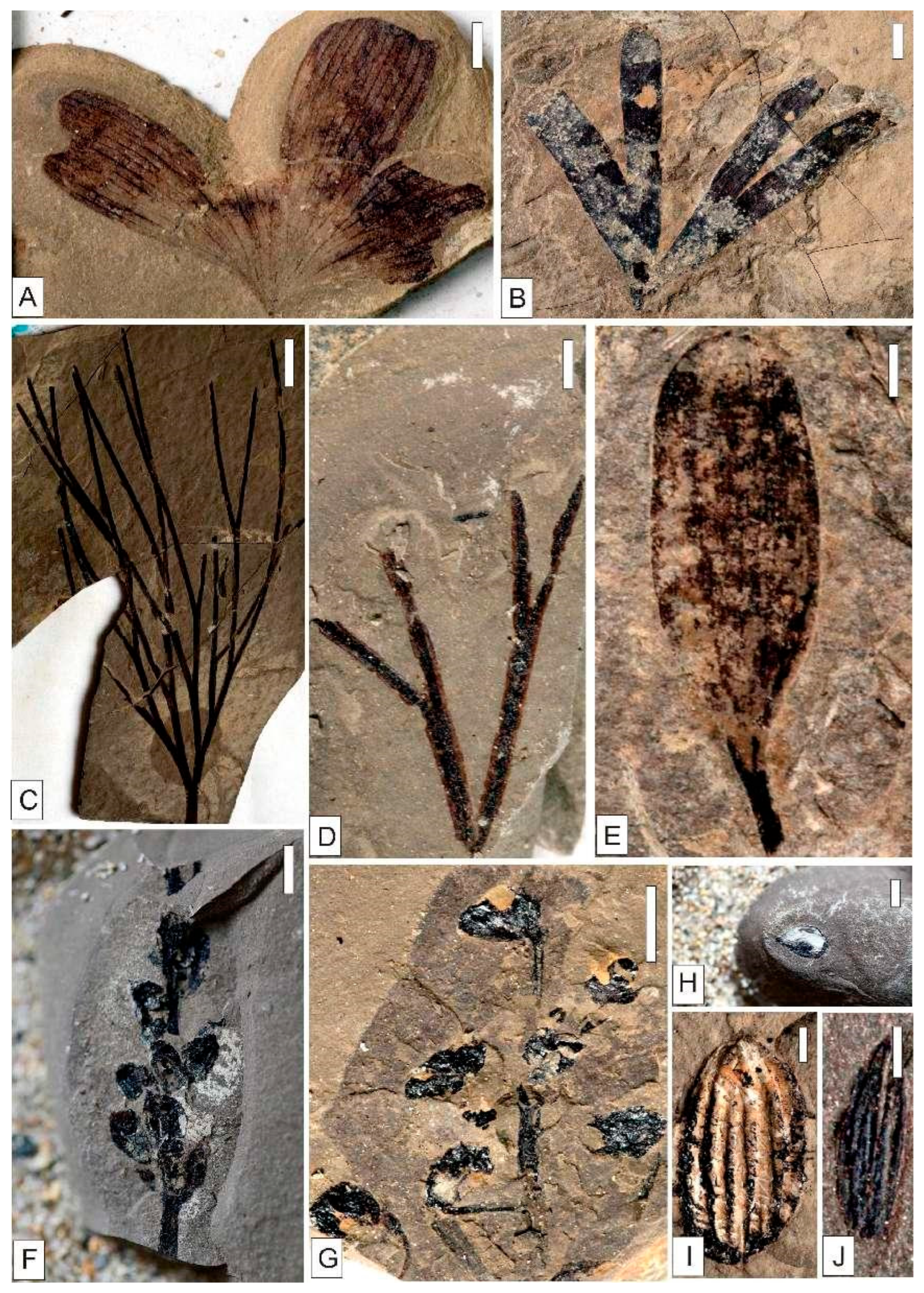

- Ginkgoopsida

- 5.

- Czekanowskiales

- 6.

- Coniferopsida

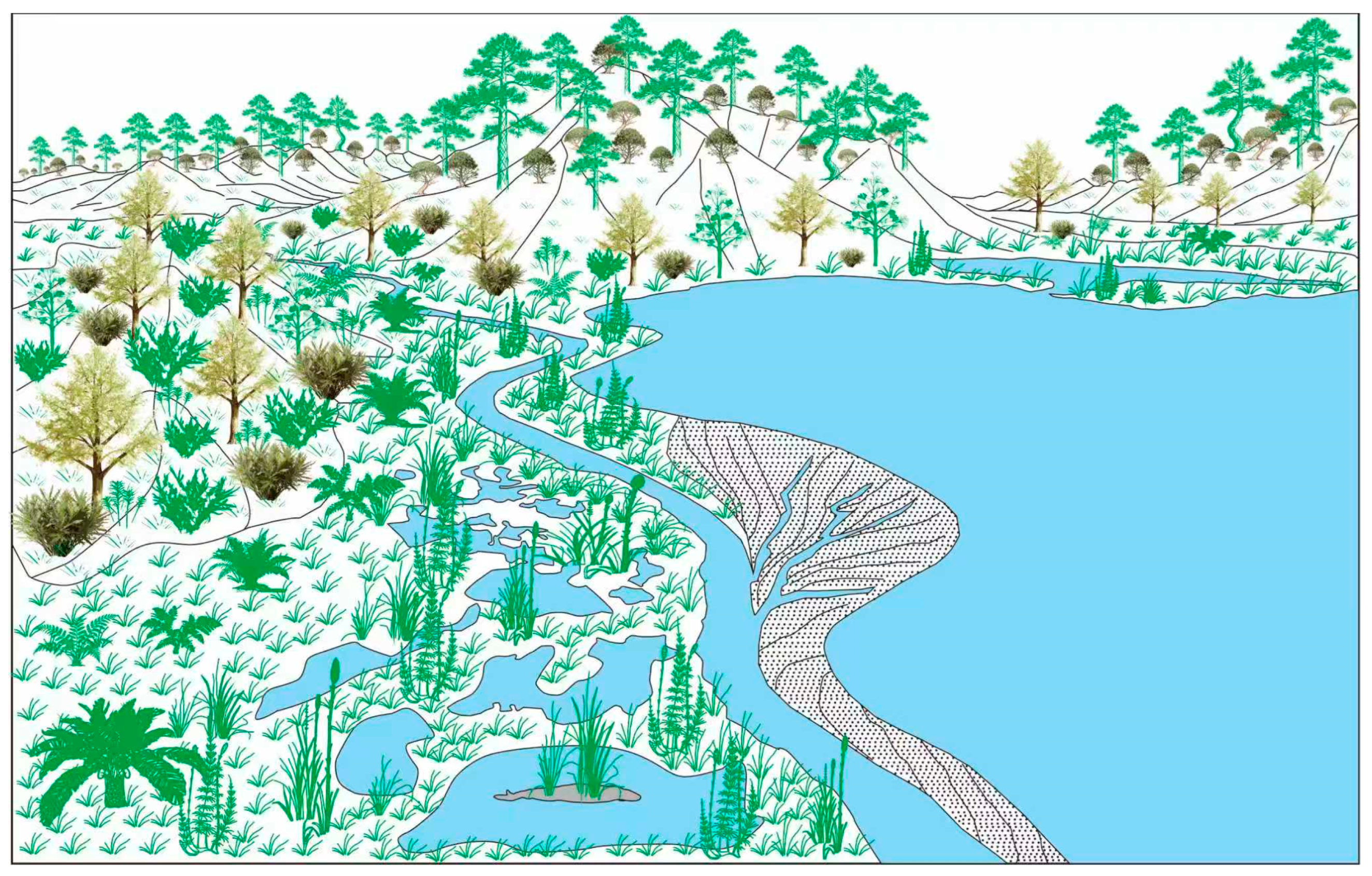

2.2.3. Reconstruction of the Yingzuilazi Formation Plant Communities

- 1.

- Riparian–Wetland Community

- 2.

- Lowland Community

- 3.

- Montane Slope Community

- 4.

- Montane Highland Community

2.3. Foliar Physiognomic Paleoclimatic Analysis of the Flora

2.3.1. Leaf Size Class Analysis

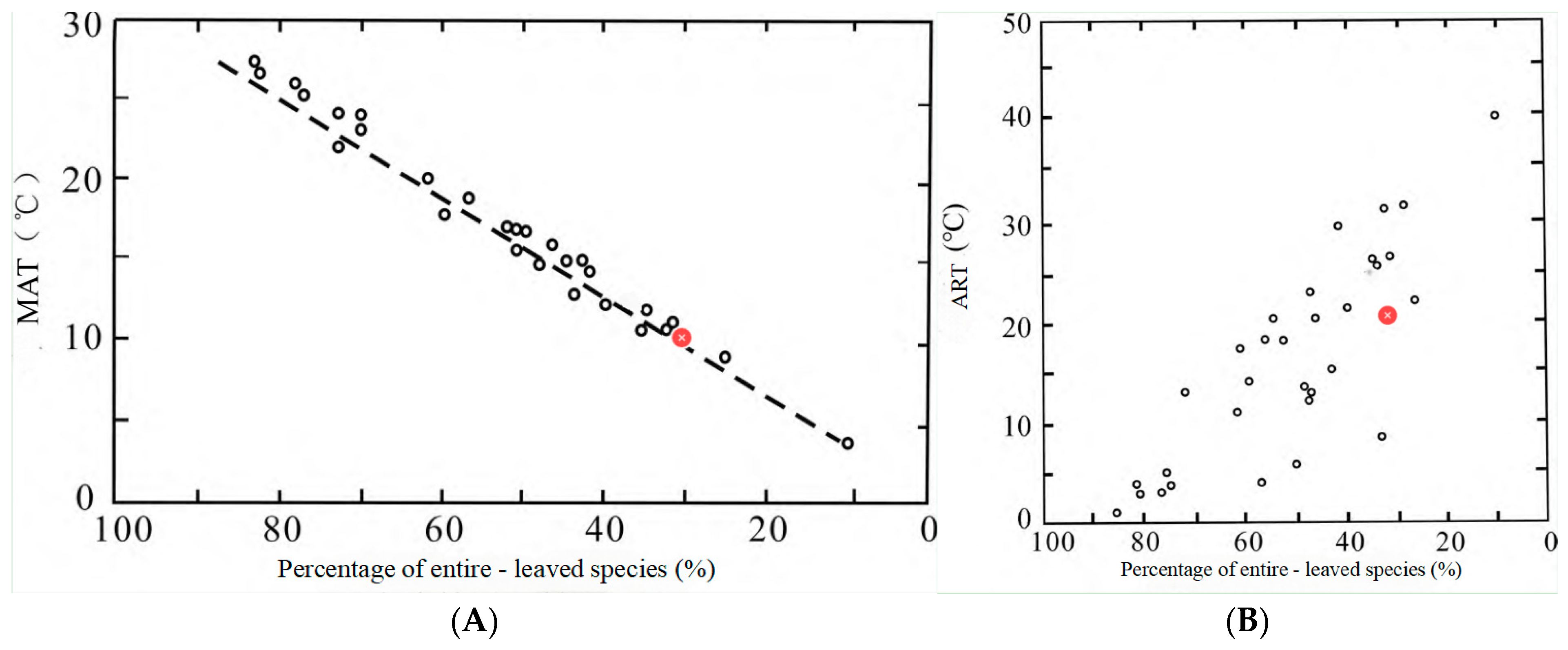

2.3.2. Leaf Margin Analysis

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chang, M.M.; Chen, P.J.; Wang, Y.Q.; Wang, Y.; Miao, D.S. The Jehol Biota: The Emergence of Feathered Dinosaurs, Beaked Birds and Flowering Plants; Shanghai Scientific & Technical Publishers: Shanghai, China, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Q.; Lv, J.C.; Gao, K.Q. The Jehol Biota in China; Geological Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.J.; Zhang, W.H.; Hu, B.; Gao, L. A New Type of Dinosaur Tracks fromLower Cretaceous of Chabu, Otog Qi, Inner Mongolia. Acta Palaeontol. Sin. 2006, 45, 221–234. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.K. Discovery and Significance of Mesozoic Jehol Biota in Qilin Hill. Master’s Thesis, China University of Geosciences, Beijing, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Cheng, X.D.; Li, W. A New Species of Cretadromus from the Lower Cretaceous Guanghua Formation in the Da Hing Gan Mountains Inner Mongolia. Geol. China 2017, 44, 818–819. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.P.; Li, J.J.; Bai, Z.Q. The First Discovery of Deinonychosaurian Tracks from Lower Cretaceous of Chabu, Otog Qi, Inner Mongolia and Its Significance. Acta Sci. Nat. Univ. Pekin. 2017, 53, 81–90. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, K.Q.; Chen, J.Y. A New Crown-Group Frog (Amphibia: Anura) from the Early Cretaceous of Northeastem Inner Mongolia, China. Am. Mus. Novit. 2017, 38, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, S.; Yang, Y.; Li, L.; Sun, D.Y.; Zhou, C.F. The First Juvenile Specimen of Manchurochelys Manchoukuoensis from the Early Cretaceous Jehol Biota. PeerJ 2017, 5, e3274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, F.M.; Gao, L.P.; Wang, J.Y. Fossil Distribution Characteristics of the Jehol Biota in Inner Mongolia and Its Palaeoclimatic and Palaeoenvironmental Significance. Geol. Resour. 2022, 31, 729–737. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Y.L.; Li, Y.; Hu, J.; Zhang, H.G. Dinosaur teeth from the Lower Cretaceous Jiufotang Formation of western Liaoning, China. PeerJ 2025, 13, 19013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Won, C.G.; So, K.S.; Pak, U.S.; Ju, I.Y.; Ri, C.J.; Jon, S.H.; Ma, J. Discovery of Early Cretaceous Sinuiju Biota in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea and Comparison with Jehol Biota in China. Cretac. Res. 2022, 139, 105303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugdaeva, E.V.; Golovneva, L.B. Siberian Jehol Biota; Geological Society: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.S.; Lin, B.; Yao, Y.L. Comparison between Mesozoic Volcanic Rock Strata in Northeast of Liaoning-South of Jilin and Yixian Formation in West of Liaoning. Acta Geol. Sin. 2016, 90, 2733–2746. [Google Scholar]

- Amiot, R.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, X.; Buffetaut, E.; Lécuyer, C.; Ding, Z.; Fluteau, F.; Hibino, T.; Kusuhashi, N.; et al. Oxygen Isotopes of East Asian Dinosaurs Reveal Exceptionally Cold Early Cretaceous Climates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 5179–5183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, M. Study on the Jehol Biota: Recent Advances and Future Prospects. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2020, 63, 757–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Wang, M.; Li, Y.; Deng, C.; He, H. New Geochronological Constraints for the Lower Cretaceous Jiufotang Formation in Jianchang Basin, NE China, and Their Implications for the Late Jehol Biota. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2021, 583, 110657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Wang, L.; Liu, J.; Deloule, E.; Hanski, E.; Gu, X.; Chen, H.; Xia, Q. Linking the Jehol Biota Evolution to the Early Cretaceous Volcanism During the North China Craton Destruction: Insights From F, Cl, S, and P. JGR Solid Earth 2022, 127, e2022JB024388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Xi, D.; Yu, Z.; Shi, Z.; Wan, X. Biotic Response to Early Cretaceous Climate Warming in Hebei, Northern China: Implications for the Phased Development of the Jehol Biota. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2022, 601, 111097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.H. Evolutionary Radiation of the Jehol Biota: Chronological and Ecological Perspectives. Geol. J. 2006, 41, 377–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Meng, Q.; Zhu, R.; Wang, M. Spatiotemporal Evolution of the Jehol Biota: Responses to the North China Craton Destruction in the Early Cretaceous. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2107859118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Zheng, S.L.; Dilcher, D.L. Early Angiosperms and Associated Floras from Western Liaoning; Shanghai Scientific & Technical Education Press: Shanghai, China, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, G.; Ji, Q.; Dilcher, D.L.; Zheng, S.; Nixon, K.C.; Wang, X. Archaefructaceae, a New Basal Angiosperm Family. Science 2002, 296, 899–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.L.; Dilcher, D.L.; Wang, H.S. A Study of Ginkgo Leaves from the Middle Jurassic of Inner Mongolia. Int. J. Plant Sci. 2008, 169, 1128–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Dilcher, D.L.; Wang, H.; Chen, Z. A Eudicot from the Early Cretaceous of China. Nature 2011, 471, 625–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilcher, D.L.; Sun, G.; Li, H. An Early Infructescence Hyrcantha decussata (Comb. Nov.) from the Yixian Formation in Northeastern China. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 9370–9374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.F.; Sun, C.L.; Li, T. Solenites (Czekanowskiales) from the Late Mesozoic Jehol Biota of Southeastern Jilin, China and Its Paleoclimatic Implications. Acta Geol. Sin. 2015, 89, 1088–1102. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, M.; Sun, C.L.; Dilcher, D.L. A New Species of Baiera from the Early Cretaceous Jehol Biota of Southeastern Jilin, China. Palaeoworld 2015, 25, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.N.; Liu, W.Z.; Su, B. Age Determination and Geological Significance of the Lower Cretaceous Yingzuilazi Formation in Baishan Basin, Southeastern Jilin. Glob. Geol. 2018, 37, 665–674. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Q.; Chen, W.; Wang, W.L.; Jin, X.C.; Zhang, J.P.; Liu, Y.Q.; Zhang, H.; Yao, P.Y.; Ji, S.; Yuan, C.X.; et al. Mesozoic Jehol Biota of Western Liaoning, China; Geological Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sui, Z.M.; Chen, Y.J. Petrogenesis of Volcanic Rocks from the Sankeyushu Formation in Southern Jilin: Evidence from Zircon U-Pb Ages and Hf Isotopes. Geoscience 2012, 26, 627–634. [Google Scholar]

- Mi, J.R.; Sun, C.L.; Sun, Y.W.; Cui, S.S.; Ai, Y.L. Plant Paleoecology and Coal Accumulation Environment of Early and Middle Jurassic in Northern Hebeiand Western Liaoning; Geological Press: Beijing, China, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.J. Plant Composition and Paleoenvironmental Analysisof Middle Jurassic Flora in Huating, Gansu Province. Master’s Thesis, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.F. Study on the Palaeoecology and Palaeogeography of the Middle Jurassic Flora in Western Hills of Beijing. Ph.D. Thesis, China University of Geosciences, Beijing, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, C.L.; Li, T.; Sun, Y.W. Several Cycad Fossils from the Early Jurassic Yihe Basin in Southern Jilin and Their Palaeoclimatic Significance. Geol. Resour. 2010, 19, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Si, X.J.; Li, X.J. Mesozoic Plants of China. In Fossil Plants of China; Science Press: Beijing, China, 1963; Volume I. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, T.N.; Taylor, E.L. The Biology and Evolution of Fossil Plants; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.R. Classification and distribution of extant cycads. J. Plants 1996, 2, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Vakhrameev, V.A. Jurassic and Early Cretaceous Floras and Paleogeographic Provinces; Nauka: Moscow, Russia, 1964; pp. 1–261. [Google Scholar]

- Vakhrameev, V.A. Jurassic and Cretaceous Floras and Climates of the Earth (In Russian); Nauka: Moscow, Russia, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Vakhrameev, V.A. Jurassic and Cretaceous Floras and Climates of the Earth; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, T.M. The Yorkshire Jurassic Flora. III. Bennettitales; British Museum (Natural History): London, UK, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.Y. An Overview of Fossil Ginkgoales. Palaeoworld 2009, 18, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, K.U.; Green, P.S. The Families and Genera of Vascular Plants; Pteridophytes and Gymnosperms; Springer-Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 1990; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Del, T.P.; Ling, H.; Guang, Y. The Ginkgos of Tian Mu Shan. Conserv. Biol. 1992, 6, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.L. Division of Early Jurassic Flora in Eurasia. Ph.D.Thesis, Jilin University, Changchun, China, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- He, S.A.; Gu, Y.; Pang, Z.J. Resources and Prospects of Ginkgo Biloba in China. In Ginkgo biloba—A Global Treasure from Biology to Medicine; Hori, T., Ridge, R.W., Tulecke, W., Eds.; Springer Verlag: Tokyo, Japan, 1997; pp. 373–383. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.W.; Liu, Z.Y.; Tan, Y.M. Investigation of Ginkgo Biloba in Jinfo Mountain. For. Res. 1999, 12, 197–201. [Google Scholar]

- Abbink, O.A.; Van Konijnenburg-Van Cittert, J.H.A.; Visscher, H. A Sporomorph Ecogroup Model for the Northwest European Jurassic-Lower Cretaceous: Concepts and Framework. Neth. J. Geosci. Geol. En Mijnb. 2004, 83, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, B.X.; Xiang, Z.; Xiang, Y.H. Wild Ginkgo in Wuchuan County, Guizhou: VII. Investigation of Ancient Ginkgo Germplasm Resources. Guizhou Sci. 2006, 24, 56–67. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, B.X.; Xiang, Z.; Xiang, Y.H. Wild Ginkgo in central Guizhou: VIII. Survey of Ginkgo germplasm resources in Guizhou. Guizhou Sci. 2007, 25, 47–55. [Google Scholar]

- Krassilov, V.A. Mesozoic Flora from the Bureja River (Ginkgoales and Czekanowskiales); Akademii Nauk SSSR: Moscow, Russia, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Krassilov, V.A. Morphology and Systematics of Ginkgos and Czekanowskias. Paleontol. J. 1972, 6, 98–102. [Google Scholar]

- Ash, S. First Occurrence of Czekanowskia (Gymnospermae, Czekanowskiales) in the United States. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 1994, 81, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, E.L.; Taylor, T.N.; Krings, M. Paleobotany: The Biology and Evolution of Fossil Plants, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.S.; Wang, Y.F.; Sun, S.G. The Quantitative Reconstruction of Paleoclimates Based on Plants. Chin. Bull. Bot. 2003, 20, 430–438. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, E.M.; Spicer, R.A.; Rees, P.M. Quantitative Palaeoclimate Estimates from Late Cretaceous and Paleocene Leaf Floras in the Northwest of the South Island, NewZealand. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2002, 184, 321–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, A. Some Limitations in Using Leaf Physiognomic Data as a Precise Method for Determining Paleoclimates with an Example from the Late Cretaceous Pautût Flora of West Greenland. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 1994, 112, 261–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, J.A. Paleoclimatic Estimates from Tertiary Leaf Assemblages. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 1995, 23, 119–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory-Wodzicki, K.M. Relationships between Leaf Morphology and Climate, Bolivia: Implications for Estimating Paleoclimate from Fossil Floras. Paleobiology 2000, 26, 668–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolph, G.E.; Dilcher, D.L. Foliar Physiognomy as an Aid in Determining Paleoclimate. Palaeontographica 1979, 170, 151–172. [Google Scholar]

- Raunkiaer, C. Life Forms of Plants and Statistical Plant Geography; The Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.H.; Zhang, S.; Jiang, Y.; Kang, M.Y.; Qiu, Y. Plant Geography, 4th ed.; Higher Education Press: Beijing, China, 2004; p. 352. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.X.; Xin, C.L.; Wang, J.J.; Di, G.Y.; Jiao, Z.P.; Zhao, H.; Wang, Z.T. Characteristics of the Middle Jurassic Flora in the Baojishan Basin, Gansu Province, and Its Study on Paleoecology and Paleoclimate. Acta Geol. Sin. 2021, 95, 3592–3605. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe, J.A. Temperature Parameters of Humid to Mesic Forests of Eastern Asia and Relation to Forests of Other Regions of the Northern Hemisphere and Australasia; United States Geological Survey Professional Paper; Library of Congress Catalog: Washington, DC, USA, 1979; p. 1106. [Google Scholar]

- Hickey, L. Stratigraphy and Paleobotany of the Golden Valley Formation (Early Tertiary) of Western North Dakota; The Geological Society of America: Boulder, CO, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B. Climatic Implication of Paleocene Flora in Altay, Xinjiang. Master’s Thesis, Graduate School of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.X. Quantitative Analysis and Spatiotemporal Distribution of Czekanowskiales Fossils in China. Master’s Thesis, Northwest Normal University, Lanzhou, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

| Stratigraphic Unit | Lithology | Interpreted Environment | Fossils |

|---|---|---|---|

| 19 | Yellow Feldspathic Quartz Sandstone | Shallow Lake Near-shore | |

| 18 | Greyish-Green Siltstone | Shallow Lake | |

| 17 | Yellow–Green Silty Mudstone Interbedded with Thin Grey Fine Sandstone | Gentle Shallow Lake Nearshore | Bivalves |

| 16 | Grey Medium-Thick-Bedded Fine Sand-stone with Thin Siltstone | Abundant Bivalves | |

| 15 | Grey–Black Siltstone | Shallow Lake | |

| 14 | Yellow–Green Argillaceous Siltstone | ||

| 13 | Grey–Green Fine Sandstone | ||

| 12 | Yellow Sandstone with Thin Grey Argilla-ceous Siltstone | Ostracods | |

| 11 | Grey Medium-Thin-Bedded Silty Mudstone | ||

| 10 | Yellow–Green, Yellow Silty Shale | Plant Fossils | |

| 9 | Light Grey, Grey Medium-Thick-Bedded Sandstone and Mudstone Interbeds | ||

| 8 | Grey Medium-Bedded Mudstone and Silty Mudstone Interbeds | Plants, Conchostracans, Bi-valves, Gastropods, Insects, Fishes, and Caudate Am-phibian | |

| 7 | Grey Mudstone with Grey–White Argilla-ceous Siltstone | ||

| 6 | Grey–Green Silty Mudstone | ||

| 5 | Yellow with Green Argillaceous Siltstone | ||

| 4 | Dark Purple Pebbly Siltstone | Braided River/Alluvial Plain | Indicative of Arid Climate |

| 3 | Dark Purple Siltstone | Braided River/Alluvial Plain | |

| 2 | Purple Pebbly Sandstone | Braided Channel |

| Class | Genus | Species | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sphenopsida | Equisetites | Equisetites cf. exiliformis Sun et Zheng; Equisetites longevaginatus Wu | 4.3 |

| Equisetostachys | Equisetostachys sp. | 2.2 | |

| Filicopsida | Todites | Todites sp. | 2.2 |

| Coniopteris | Coniopteris angustiloba Brick; Coniopteris sp. | 4.3 | |

| Gleichenites | Gleichenites sp. | 2.2 | |

| Cycadopsida | Tyrmia | Tyrmia cf. acrodonta Wu | 2.2 |

| Ginkgoopsida | Ginkgo | Ginkgo huttoni (Sternberg) Heer | 2.2 |

| Ginkgoites | Ginkgoites sibiricus (Heer) Seward | 2.2 | |

| Pseudotorellia | Pseudotorellia sp. | 2.2 | |

| Baiera | Baiera baishanensis Zhao et Sun; Baiera sp. | 4.3 | |

| Czekanowskiales | Czekanowskia | Czekanowskia setacea Heer; Czekanowskiales sp. | 4.3 |

| Phoenicopsis | Phoenicopsis sp.; Phoenicopsis (Culgoweria) uralensis Kiritchkova | 4.3 | |

| Solenites | Solenites baishanensis Li et Sun; Solenites murrayana Lindley et Hutton; Solenites gracilis Li et Sun; Solenites sp.1; Solenites sp.2 | 10.9 | |

| Sphenarion | Sphenarion sp.1; Sphenarion sp.2 | 4.3 | |

| Ixostrobus | Ixostrobus delicatus Sun et Zheng | 2.2 | |

| Coniferopsida | Pityocladus | Pityocladus sp.1; Pityocladus sp.2 | 4.3 |

| Pityophyllum | Pityophyllum staratschini (Heer) Nathorst; Pityophyllum lindstroemi Nathorst; Pityophyllum sp.1; Pityophyllum sp.2 | 8.7 | |

| Pityospermum | Pityospermum sp.1; Pityospermum sp.2 | 4.3 | |

| Schizolepis | Schizolepis moelleri Seward | 2.2 | |

| Scarburgia | Scarburgia hillii Harris | 2.2 | |

| Ferganiella | Ferganiella podozamioides Lih; Ferganiella sp. | 4.3 | |

| Lindleycladus | Lindleycladus sp. | 2.2 | |

| Podozamites | Podozamites spp. | 2.2 | |

| Gentopsida | Ephedra | Ephedra sp. | 2.2 |

| Ephedrites | Ephedrites sp. | 2.2 | |

| Fructus et Semina | Strobilites | Strobilites sp.1; Strobilites sp.2 | 4.3 |

| Carpolithus | Carpolithus sp.1; Carpolithus sp.2; Carpolithus spp. | 6.5 |

| Burial Type | Autochthonous/Parautochthonous | Allochthonous | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Criterion | |||

| Preservation State | Well preserved; possess rhizomes, stoloniferous bases, root remnants, or rhizomorphic structures; leaf outlines distinct and venation patterns clearly identifiable. | Highly fragmented with low completeness. | |

| Sorting Condition | Variable size and diverse taxa. | Uniform size with mass accumulation. | |

| Orientation Pattern | No preferred orientation. | Exhibits preferred orientation. | |

| Organ Resist | Thin-textured leaves and strobiloid reproductive organs. | Well-preserved coriaceous leaves. | |

| Species | Stratum | Host Rock | Abundance | Preservation State | Burial Style |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Equisetites cf. exiliformis Sun et Zheng | K1y | gray–yellow sandstone | ++ | leaf sheaths intact, possess sclerified ridges, distinct longitudinal grooves | autochthonous |

| Equisetites longevaginatus Wu | K1y | gray–yellow sandstone | ++ | leaf sheaths intact, possess sclerified ridges, distinct longitudinal grooves | autochthonous |

| Equisetostachys sp. | K1y | gray–yellow sandstone | + | strobili with small scutella, basal stalks connected to stems | autochthonous |

| Coniopteris angustiloba Brick | K1y | gray–yellow sandstone | +++ | bipinnate fronds, clear venation, rachises showing distinct longitudinal striations | autochthonous |

| Coniopteris sp. | K1y | gray–yellow sandstone | ++ | bipinnate fronds, clear venation, rachises showing distinct longitudinal striations | autochthonous |

| Tyrmia cf. acrodonta Wu | K1y | gray siltstone | + | pinnae attached to rachis, lobes largely intact, clear venation | parautochthonous |

| Ginkgo huttoni (Sternberg) Heer | K1y | gray mudstone | +++ | leaves intact, clear venation | autochthonous |

| Ginkgoites sibiricus (Heer) Seward | K1y | gray–yellow siltstone | ++ | leaves intact, clear venation | autochthonous |

| Pseudotorellia sp. | K1y | gray–yellow sandstone | ++ | leaves largely intact, clear venation | parautochthonous |

| Baiera baishanensis Zhao et Sun | K1y | gray–yellow siltstone | +++ | leaves intact, clear venation | autochthonous |

| Baiera sp. | K1y | gray–yellow sandstone | + | leaves largely intact, venation indistinct | parautochthonous |

| Czekanowskia setacea Heer | K1y | gray mudstone | ++ | leaves largely intact, venation indistinct | parautochthonous |

| Czekanowskiales sp. | K1y | gray–yellow siltstone | + | leaves largely intact, clear venation | autochthonous/parautochthonous |

| Phoenicopsis sp. | K1y | yellow siltstone | +++ | leaves largely intact, clear venation | autochthonous |

| Phoenicopsis (Culgoweria) uralensis Kiritchkova | K1y | yellow–green mudstone | +++ | linear leaves clustered on short shoots, leaves complete, clear venation | autochthonous |

| Solenites baishanensis Li et Sun | K1y | yellow siltstone | +++ | linear leaves clustered on short shoots, leaves complete, clear venation | autochthonous |

| Solenites murrayana Lindley et Hutton | K1y | yellow–green sandstone | +++ | leaves largely intact, venation indistinct | autochthonous |

| Solenites gracilis Li et Sun | K1y | gray–yellow mudstone | +++ | short shoots present, leaves complete, clear venation | autochthonous |

| Solenites sp.1 | K1y | yellow–green siltstone | +++ | short shoots present, leaves complete, clear venation | autochthonous |

| Sphenarion sp.1 | K1y | gray–yellow mudstone | + | leaves largely intact, clear venation | parautochthonous |

| Ixostrobus delicatus Sun et Zheng | K1y | yellow–green siltstone | ++ | structures complete | autochthonous |

| Pityocladus sp.1 | K1y | yellow–green siltstone | + | structures largely complete | parautochthonous |

| Pityophyllum staratschini (Heer) Nathorst | K1y | yellow–green sandstone | +++ | structures complete | autochthonous |

| Pityophyllum lindstroemi Nathorst | K1y | yellow sandstone | +++ | leaves intact, clear venation | autochthonous |

| Pityophyllum sp.1 | K1y | yellow–green sandstone | +++ | leaves intact, clear venation | autochthonous |

| Pityospermum sp.1 | K1y | yellow–green sandstone | + | structures complete | autochthonous/parautochthonous |

| Schizolepis moelleri Seward | K1y | gray mudstone | ++ | structures complete | autochthonous |

| Scarburgia hillii Harris | K1y | gray–yellow sandstone | + | structures complete | autochthonous/parautochthonous |

| Ferganiella podozamioides Lih | K1y | gray–yellow siltstone | ++ | leaves complete, dichotomous branching, clear venation | autochthonous |

| Ferganiella sp. | K1y | gray sandstone | +++ | leaves intact, clear venation | autochthonous |

| Lindleycladus sp. | K1y | gray–yellow mudstone | +++ | leaves intact, clear venation | autochthonous |

| Ephedra sp. | K1y | yellow–green sandstone | + | structures complete | autochthonous/ parautochthonous |

| Strobilites sp.1 | K1y | gray sandstone | ++ | structures largely complete | autochthonous |

| Carpolithus sp.1 | K1y | gray–yellow sandstone | +++ | structures complete | autochthonous |

| Community Type (Location) | Leptophyll | Nanophyll | Microphyll | Mesophyll | Macrophyll | Megaphyll |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tropical Rainforest (Africa, Eastern Ecuador) 1 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 64 | 27 | 0 |

| Tropical Rainforest (Brazil, 1°27′ S) 1 | 2.3 | 3.2 | 15.1 | 68.3 | 11.0 | 0 |

| Temperate Rainforest (Brazil, Caioba 26° S) 1 | 0 | 8.8 | 14.4 | 64.4 | 11.1 | 1.1 |

| Evergreen Broadleaved Forest (Zhejiang, China) 1 | 0 | 4.1 | 53.3 | 37.1 | 5.4 | 0 |

| Evergreen Broadleaved Forest (Lushan, China, 29°35′ N) 1 | 0 | 7.0 | 52.9 | 39.7 | 0.4 | 0 |

| Baojishan Yaojie Formation Flora (Gansu) 2 | 7.8 | 13.3 | 40.7 | 25.0 | 15.2 | 0 |

| Temperate Montane Coniferous Forest (Changbai Mountains) 1 | 6.5 | 13.0 | 39.5 | 31.8 | 8.8 | 0 |

| Baishan Yingzuilazi Formation Flora | 7.1 | 13.0 | 40.1 | 28.6 | 11.2 | 0 |

| Flora or Vegetation Type | Entire Margins (%) | Climatic Zone | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fossil Floras | Xinjiang Altay Fossil Flora (Paleocene) 3 | 77 | Tropical |

| Bear Den Member (Late Eocene) 1 | 33 | Warm–Temperate | |

| Baishan Early Cretaceous Flora | 30.4 | Temperate | |

| Gansu Baojishan Flora (Middle Jurassic) 4 | 35.4 | Warm–Temperate | |

| Chalk Bluffs (Middle Eocene) 1 | 46 | Orizaban Subtropical | |

| Wilcox (Eocene) 1 | 83 | Tropical | |

| Modern Vegetation | Pennsylvania 1 | 30 | Temperate |

| Evergreen Broadleaf Forest (Zhejiang) 2 | 46 | Subtropical | |

| Taiwan (0–500 m elev.) 1 | 61 | Subtropical | |

| Philippines 1 | 76 | Tropical | |

| Panama Lowland Rainforest 1 | 88 | Tropical |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Huang, W.; Zhang, D. Applying Flora Composition and Leaf Physiognomy to Reconstruct the Paleocommunity, Palaeoclimate, and Paleoenvironment of the Jehol Biota in Jilin, China. Plants 2026, 15, 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010022

Huang W, Zhang D. Applying Flora Composition and Leaf Physiognomy to Reconstruct the Paleocommunity, Palaeoclimate, and Paleoenvironment of the Jehol Biota in Jilin, China. Plants. 2026; 15(1):22. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010022

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Wei, and Dejun Zhang. 2026. "Applying Flora Composition and Leaf Physiognomy to Reconstruct the Paleocommunity, Palaeoclimate, and Paleoenvironment of the Jehol Biota in Jilin, China" Plants 15, no. 1: 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010022

APA StyleHuang, W., & Zhang, D. (2026). Applying Flora Composition and Leaf Physiognomy to Reconstruct the Paleocommunity, Palaeoclimate, and Paleoenvironment of the Jehol Biota in Jilin, China. Plants, 15(1), 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010022