Root–Canopy Coordination Drives High Yield and Nitrogen Use Efficiency in Dryland Winter Wheat

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Divergence in Yield Component Characteristics Among Winter Wheat Cultivar Types

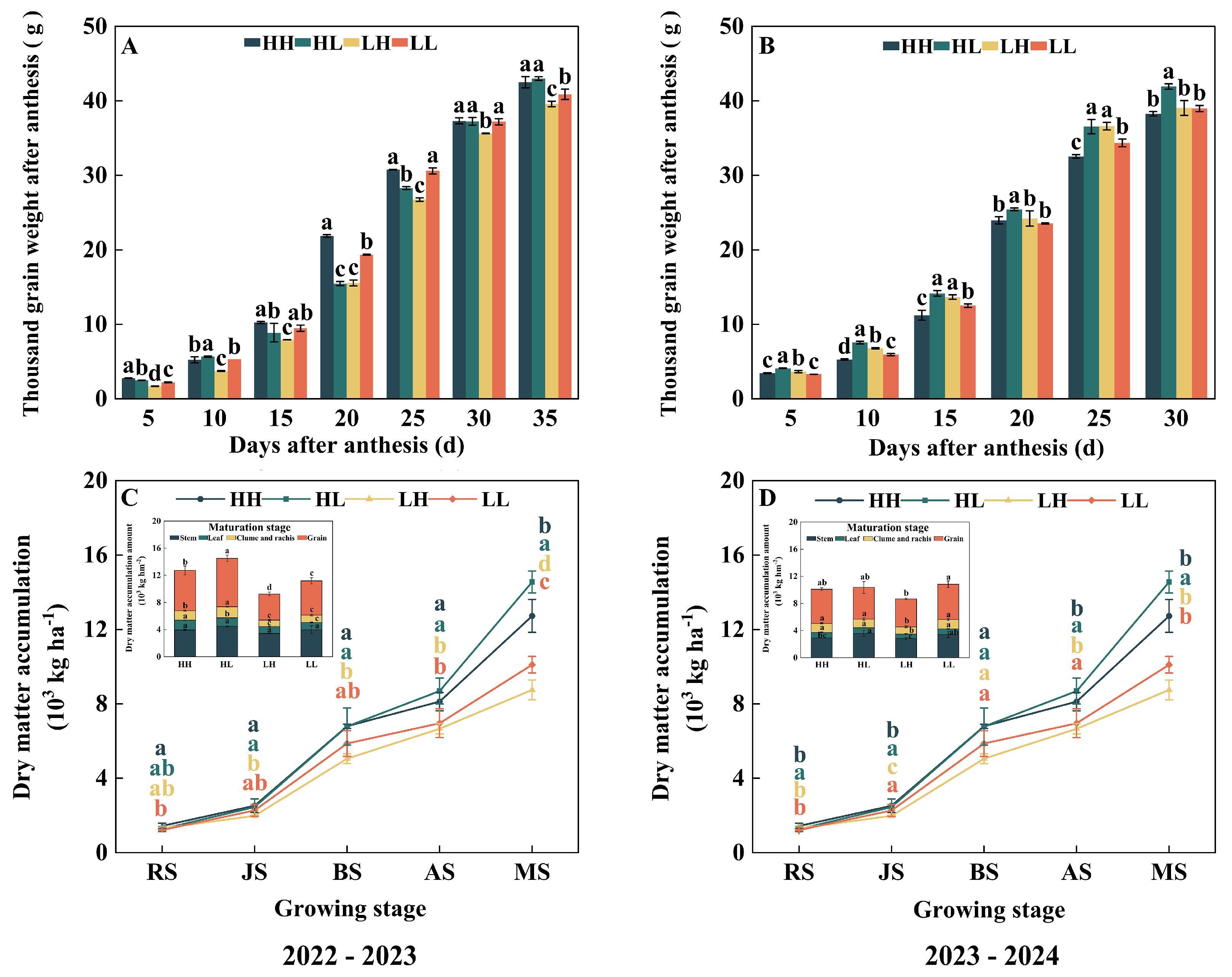

2.2. Grain-Filling Kinetics

2.3. Dry Matter Accumulation Characteristics and Organ Allocation Patterns

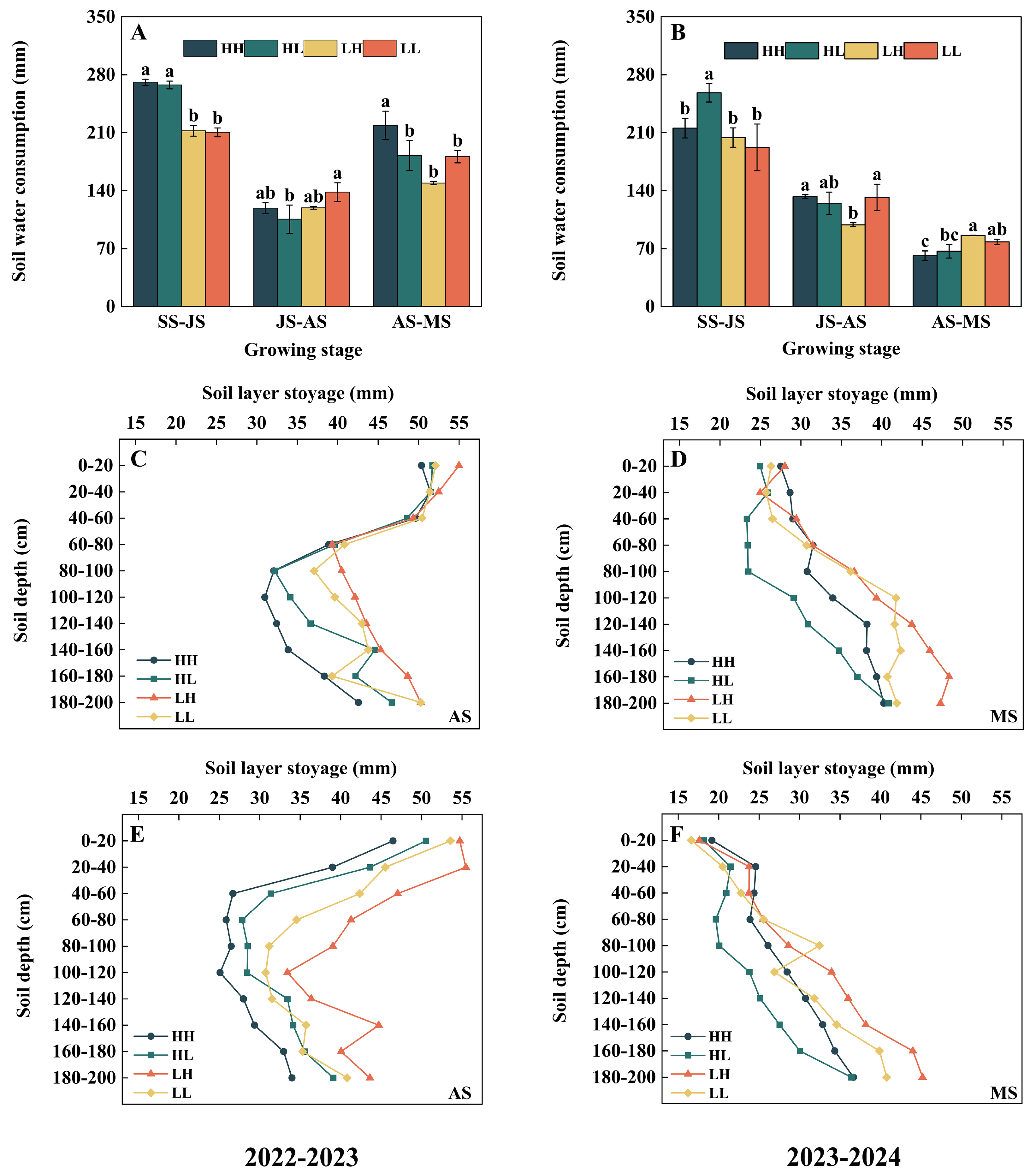

2.4. Soil Water Consumption Dynamic Characteristics

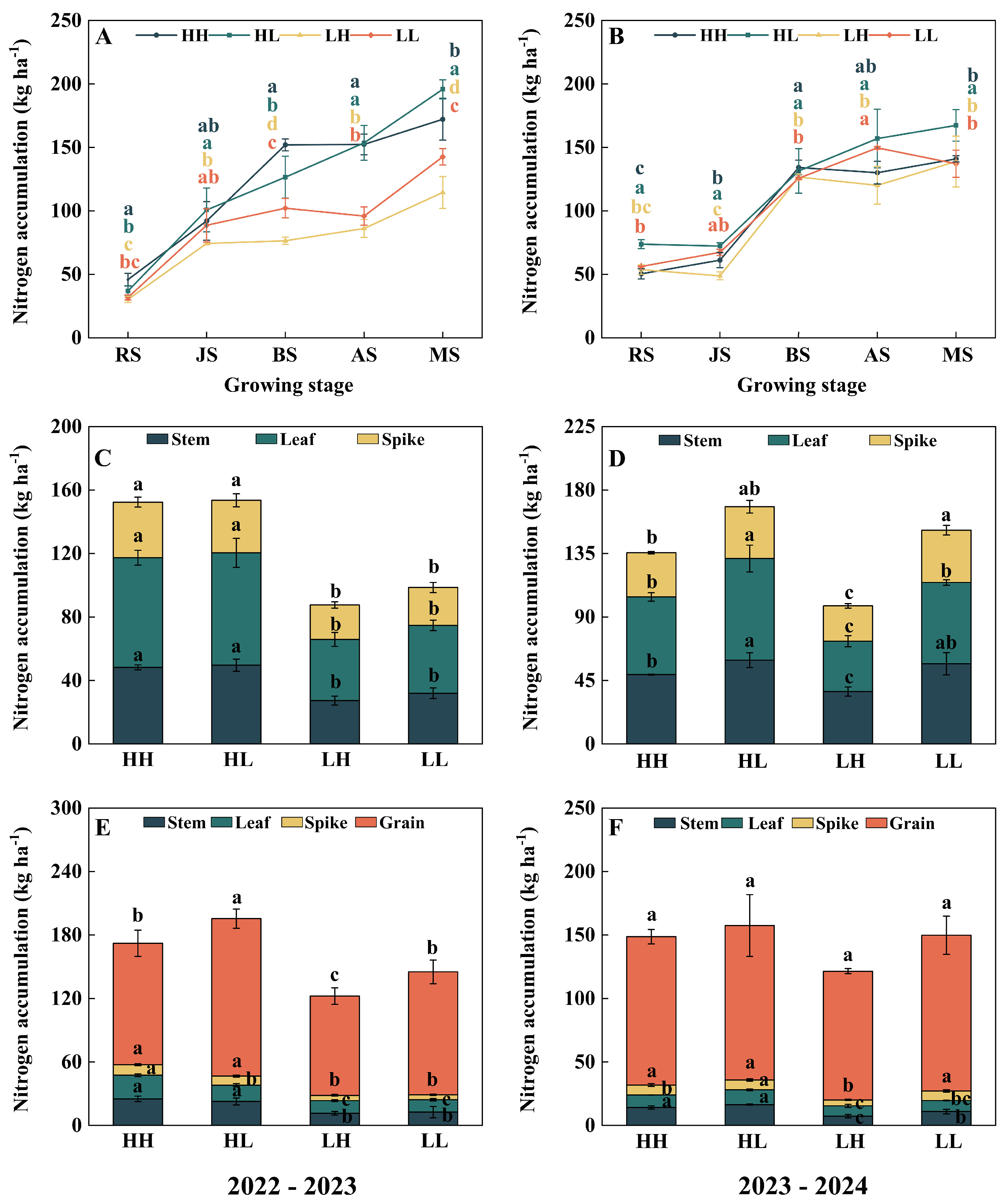

2.5. Nitrogen Dynamic Characteristics

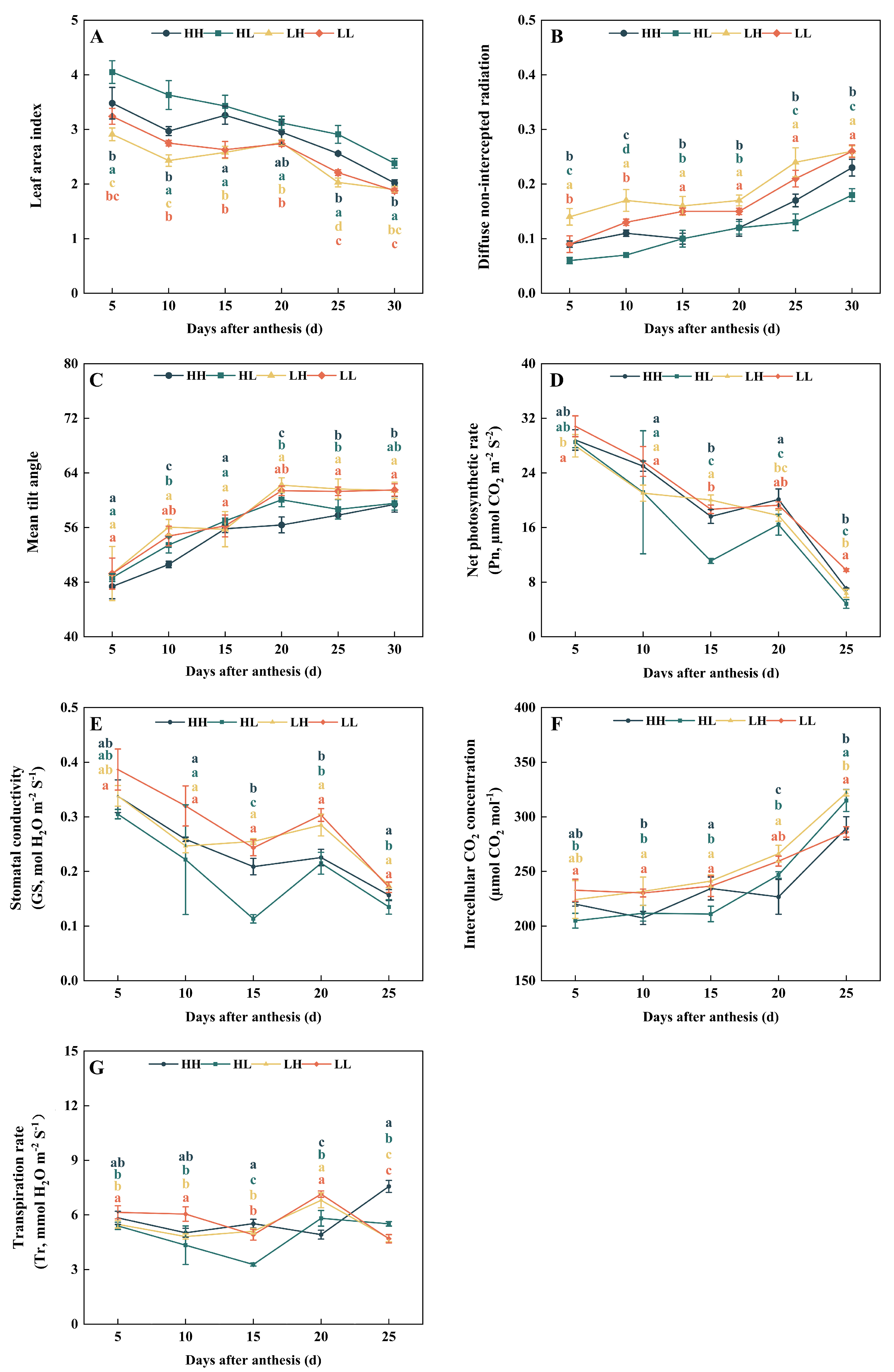

2.6. Root–Canopy Structure

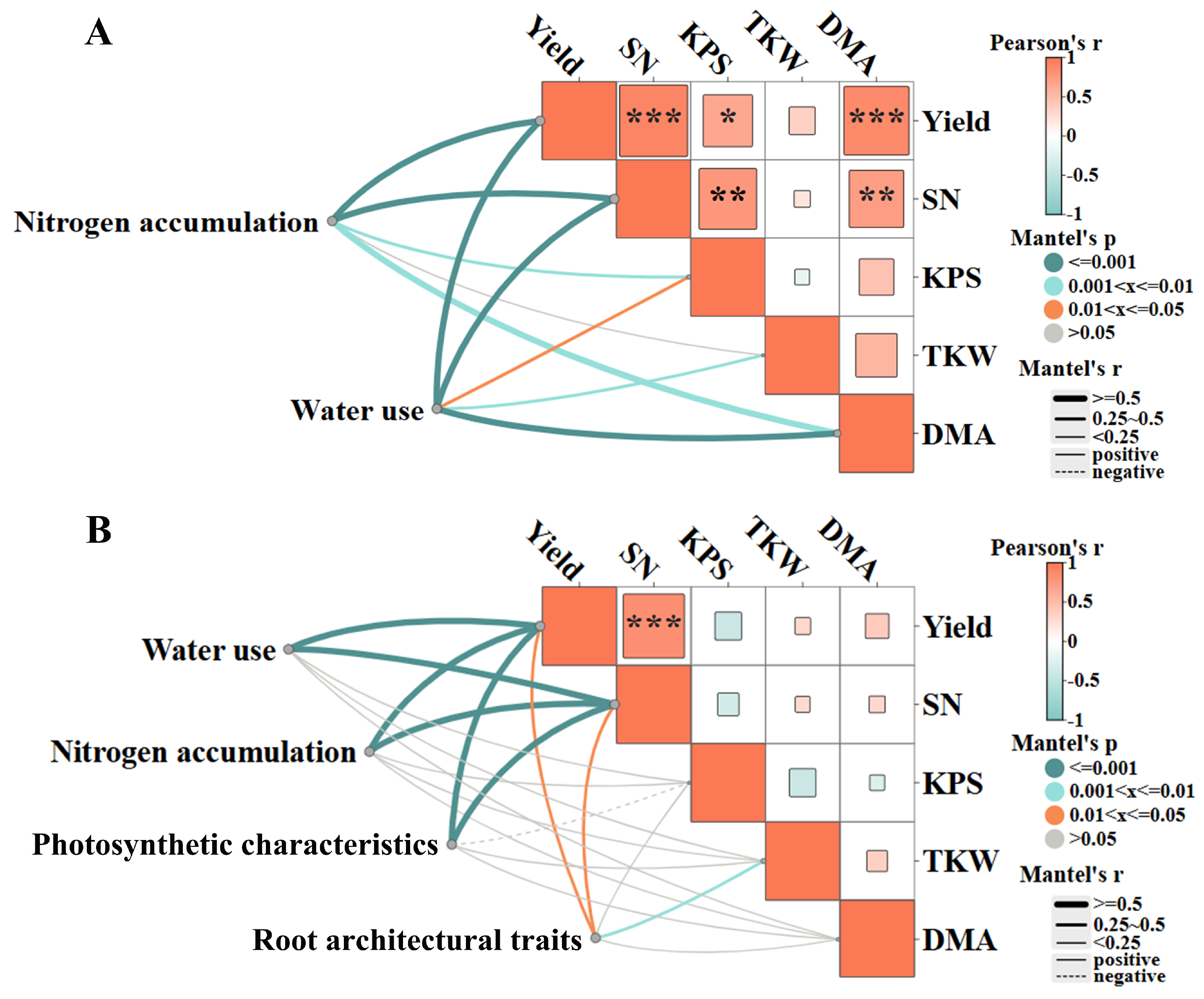

2.7. Analysis of the Association Between Factors Influencing Wheat Yield Formation

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Experimental Material

4.2. Experiment Design

4.3. Dry Matter Accumulation and Translocation

4.4. Grain Yield and Its Components

4.5. Grain Filling

4.6. Water Determination

4.7. Nitrogen Accumulation, Transport and Nitrogen Use Efficiency

4.8. Root Morphological Traits

4.9. Canopy and Photosynthetic Characteristics

4.10. Data Analysis

4.10.1. Variety Classification

4.10.2. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HH | High-yield and high-efficiency |

| HL | High-yield and low-efficiency |

| LH | Low-yield and high-efficiency |

| LL | Low-yield and low-efficiency |

| WUE | Water use efficiency |

| NUE | Nitrogen use efficiency |

| Rmean | Average grain-filling rate |

| t1 | The fast-filling phase duration |

| t2 | The slow-filling phase duration |

| Tmax | Time to maximum grain-filling rate |

| T | The total grain-filling duration |

| Rmax | Maximum grain-filling rate |

| RLD | Root length density |

| RSD | Root surface area density |

| RVD | Root volume density |

| RDWD | Root dry weight density |

| LAI | Leaf area index |

| DIFN | Diffuse non-intercepted radiation |

| MTA | Mean tilt angle |

| SN | Spike number |

| KPS | Kernels per spike |

| TKW | Thousand-kernel weight |

| DMA | Dry matter accumulation |

| SS | Sowing stage |

| RS | Returning green stage |

| JS | Jointing stage |

| BS | Booting stage |

| AS | Anthesis stage |

| MS | Maturity stage |

| Pn | Net photosynthetic rate |

| GS | Stomatal conductance |

| Ci | Intercellular CO2 concentration |

| Tr | Transpiration rate |

References

- Ma, X.L.; Wang, Z.H.; Cao, H.B.; She, X.; He, H.X.; Song, Q.Y.; Liu, J.S. Yield variation of winter wheat and its relation to yield components, NPK uptake and utilization in drylands of the Loess Plateau. J. Plant Nutr. Fertil. 2017, 23, 1135–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Sadras, V.; Chen, X.P.; Zhang, F.S. Water use efficiency of dryland wheat in the loess plateau in response to soil and crop management. Field Crops Res. 2013, 151, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.X.; Xu, B.C.; Yin, L.N.; Wang, S.W.; Zhang, S.Q.; Shan, L.; Kwak, S.S.; Ke, Q.B.; Deng, X.P. Dryland agricultural environment and sustainable productivity. Plant Biotechnol. Rep. 2020, 14, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, E.K.; Mei, X.R.; Yan, C.R.; Gong, D.Z.; Zhang, Y.Q. Effects of water stress on photosynthetic characteristics, dry matter translocation and WUE in two winter wheat genotypes. Agric. Water Manag. 2016, 167, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, W.F.; Tränkner, M.; Lu, J.W.; Yan, J.Y.; Huang, S.Y.; Ren, T.; Cong, R.H.; Li, X.K. Interactive effects of nitrogen and potassium on photosynthesis and photosynthetic nitrogen allocation of rice leaves. BMC Plant Biol. 2019, 19, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Wang, G.D.; Tang, Q.Y.; Song, Z.W.; Luo, H.H.; Li, Y.X. Nitrogen supply under mulched drip irrigation increases the rice yield by improving the photosynthetic nitrogen distribution strategy and promoting biomass accumulation. Agric. Manag. Water 2025, 320, 109839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.W.; Serret, M.D.; Elazab, A.; Pie, J.B.; Araus, J.L.; Aranjuelo, I.; Sanz-Sáez, A. Wheat ear carbon assimilation and nitrogen remobilization contribute significantly to grain yield. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2016, 58, 914–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.X.; Whalley, P.A.; Ashton, R.W.; Evans, J.; Hawkesford, M.J.; Griffiths, S.; Huang, D.Z.; Zhou, H.; Mooney, S.J.; Whalley, W.R. A comparison between water uptake and root length density in winter wheat: Effects of root density and rhizosphere properties. Plant Soil 2020, 451, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Q.; Zhang, H.Y.; He, J.N.; Li, H.R.; Wang, H.G.; Li, D.X.; Lv, X.K.; Li, R.Q. Water use strategies and shoot and root traits of high-yielding winter wheat cultivars under different water supply conditions. Agronomy 2024, 14, 826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, J.P. Root phenes that reduce the metabolic costs of soil exploration: Opportunities for 21st century agriculture. Plant Cell Environ. 2015, 38, 1775–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasson, A.P.; Richards, R.A.; Chatrath, R.; Misra, S.C.; Prasad, S.V.S.; Rebetzke, G.J.; Kirkegaard, J.A.; Christopher, J.; Watt, M. Traits and selection strategies to improve root systems and water uptake in water-limited wheat crops. J. Exp. Bot. 2012, 63, 3485–3498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Y.; Dai, X.L.; Shi, Y.H.; Cao, Q.; Men, H.W.; He, M.R. Effects of leaf area index on photosynthesis and yield of winter wheat after anthesis. J. Plant Nutr. Fertil. 2012, 18, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.Y.; Xu, S.J.; Wei, Q.R.; Yang, Y.X.; Pan, H.Q.; Fu, X.L.; Fan, Z.H.; Qin, B.T.; Wang, X.C.; Ma, X.M.; et al. Variation in leaf type, canopy architecture, and light and nitrogen distribution characteristics of two winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) varieties with high nitrogen-use efficiency. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.H.; Xu, K.; Zhao, K.; Sun, J.J.; Wei, H.H.; Xu, J.W.; Wei, H.Y.; Guo, B.W.; Huo, Z.Y.; Dai, Q.G.; et al. Canopy structure and photosynthetic characteristics of Yongyou series of Indica-Japonica hybrid rice under high-yielding cultivation condition. Acta Agron. Sin. 2015, 41, 286–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.Q.; Tang, L.; Zhang, W.Y.; Cao, W.X.; Zhu, Y. Dynamic analysis on response of dry matter accumulation and partitioning to nitrogen fertilizer in wheat cultivars with different plant types. Acta Agron. Sin. 2009, 35, 2258–2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.Y.; Wang, G.D.; Zhao, L.; Song, Z.W.; Li, Y.X. Responses of yield, root traits and their plasticity to the nitrogen environment in nitrogen-efficient cultivars of drip-irrigated rice. J. Integr. Agric. 2025, 24, 480–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joudi, M.; Van Den Ende, W. Genotypic variation in pre- and post-anthesis dry matter remobilization in iranian wheat cultivars: Associations with stem characters and grain yield. Czech J. Genet. Plant Breed. 2018, 54, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, I.S.A.; Nakata, N. Remobilization of nitrogen and carbohydrate from stems of bread wheat in response to heat stress during grain filling. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 2005, 191, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tegeder, M.; Daubresse, C.M. Source and sink mechanisms of nitrogen transport and use. New Phytol. 2017, 217, 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.C.; Zhang, J.H. Grain filling of cereals under soil drying. New Phytol. 2006, 169, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzid, A.; Arous, A.; Felouah, O.C.; Merah, O.; Adda, A. Contribution of current photosynthesis and reserves remobilization in grain filling and its composition of durum wheat under different water regimes. Acta Univ. Agric. Silvic. Mendel. Brun. 2020, 68, 937–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Kumar, T.; Foulkes, M.J.; Orford, S.; Singh, A.M.; Wingen, L.U.; Karnam, V.; Nair, L.S.; Mandal, P.K.; Griffiths, S. Nitrogen uptake and remobilization from pre- and post-anthesis stages contribute towardsgrain yield and grain protein concentration in wheat grown in limited nitrogen conditions. CABI Agric. Biosci. 2023, 4, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Bueren, E.T.L.; Struik, P.C. Diverse concepts of breeding for nitrogen use efficiency. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 37, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manna, M.; Rengasamy, B.; Sinha, A.K. Nutrient and water availability influence rice physiology, root architecture and ionomic balance via auxin signalling. Plant Cell Environ. 2025, 48, 2691–2705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jian, J.J.; Cui, N.; Liu, T.Y.; Zhang, W.F.; Zhang, Y.L. Effect of drought and lower canopy shading on the light energy utilization capacity of upper leaves in cotton. Cotton Sci. 2025, 37, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Chen, W.W.; Jing, M.Y.; Gao, Y.M.; Wang, Z.M. Canopy structure, light intensity, temperature and photosynthetic performance of winter wheat under different irrigation conditions. Plants 2023, 12, 3482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Neng, F.R.; Xiong, S.P.; Wei, Y.H.; Cao, R.; Wei, Q.R.; Ma, X.M.; Wang, X.C. Canopy light distribution effects on light use efficiency in wheat and its mechanism. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 10, 1023117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zheng, B.Y.; He, Y. Improving grain yield via promotion of kernel weight in high yielding winter wheat genotypes. Biology 2021, 11, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, M.; Sharifi, P.; Karimizadeh, R.; Shefazadeh, M.K. Relationships between grain yield and yield components in bread wheat under different water availability (dryland and supplemental irrigation conditions). Not. Bot. Horti Agrobot. Cluj-Napoca 2012, 40, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manschadi, A.M.; Christopher, J.; Devoil, P.; Hammer, G.L. The role of root architectural traits in adaptation of wheat to water-limited environments. Funct. Plant Biol. 2006, 33, 823–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singels, A.; Smit, M.A.; Redshaw, K.A.; Donaldson, R.A. The effect of crop start date, crop class and cultivar on sugarcane canopy development and radiation interception. Field Crops Res. 2005, 92, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, A. Effective use of water (EUW) and not water-use efficiency (WUE) is the target of crop yield improvement under drought stress. Field Crops Res. 2009, 112, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.J.; Yu, Z.W.; Shi, Y.; Liang, P. Differences in water consumption of wheat varieties are affected by root morphology characteristics and post-anthesis root senescence. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 12, 814658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.S.; Zhou, X.X.; Cui, Y.M.; Zhou, K.; Zhu, C.J.; Luan, Q.H. Soil moisture contribution to winter wheat water consumption from different soil layers under straw returning. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, S.D. Soil and Agricultural Chemistry Analysis, 3rd ed.; China Agriculture Press: Beijing, China, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.J.; Cheng, H.B.; Chai, S.X.; Zhang, B.; Li, R. Effect of different mulching cultivation methods on dry matter distriution and translocation in winter wheat. J. Triticeae Crops 2021, 41, 745–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Chai, Y.W.; Chang, L.; Wang, Z.Y.; Li, Y.Z.; Ma, J.H.; Xu, W.J.; Liu, X.F.; Chai, N.Y.; Huang, C.X. Effects of different mulching treatments on accumulation andtranslocation of dry matter and yield in winter wheat. Agric. Res. Arid Areas 2024, 42, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.R.; Zhong, R.; Sun, M.; Kong, W.L.; Zhang, J.J.; Hafeez, N.; Ran, A.X.; Lin, W.; Cao, Z.X. Nitrogen application rates at rainfall gradients regulate water andnitrogen use efficiency in dryland winter wheat. J. Plant Nutr. Fertil. 2022, 28, 1430–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.J.; Zhen, Q.; Ma, W.M.; Jia, J.C.; Li, P.F.; Zhang, X.C. Dynamic responses of soil aggregate-associated organic carbon and nitrogen to different vegetation restoration patterns in an agro-pastoral ecotone in northern China. Ecol. Eng. 2023, 189, 106895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.N.; Shen, D.D.; Ding, Y.G.; Li, Z.H.; Zhu, M.; Li, C.Y.; Zhu, X.K.; Ding, J.F.; Guo, W.S. Effect of nitrogen reduction models on grain yield, quality and nitrogen efficiency of medium–gluten wheat following rice. J. Triticeae Crops. 2021, 41, 1524–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.Y.; Zhou, Z.C.; Han, W.X. Effects of herbaceous root growth on soil resistance to erosion under different planting densities. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2025, 39, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | Varieties Type | t1 (d) | t2 (d) | Rmax (g 1000-Grain−1 d−1) | Tmax (d) | Rmean (g 1000-Grain−1 d−1) | T (d) | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2022–2023 | HH | 14.11 ± 0.15 b | 24.30 ± 0.11 c | 2.14 ± 0.04 ab | 20.67 ± 0.12 c | 1.00 ± 0.01 b | 44.72 ± 0.01 b | 0.998 |

| HL | 16.24 ± 0.06 a | 27.42 ± 0.21 a | 1.69 ± 0.71 b | 23.43 ± 0.11 a | 1.01 ± 0.01 b | 49.82 ± 0.75 a | 0.996 | |

| LH | 16.13 ± 0.23 a | 25.90 ± 0.54 b | 2.21 ± 0.02 a | 22.42 ± 0.44 b | 0.97 ± 0.01 c | 45.48 ± 0.84 b | 0.998 | |

| LL | 14.26 ± 0.21 b | 23.55 ± 0.11 c | 2.28 ± 0.05 a | 20.24 ± 0.15 c | 1.03 ± 0.01 a | 42.19 ± 0.09 c | 0.998 | |

| 2023–2024 | HH | 13.31 ± 0.16 a | 22.43 ± 0.53 a | 2.32 ± 0.22 a | 19.18 ± 0.31 a | 1.06 ± 0.08 a | 40.71 ± 1.25 b | 0.998 |

| HL | 12.39 ± 0.27 b | 22.97 ± 0.22 a | 2.14 ± 0.17 a | 19.20 ± 0.19 a | 1.05 ± 0.06 a | 44.19 ± 0.51 a | 0.998 | |

| LH | 12.59 ± 0.36 b | 21.98 ± 0.82 a | 2.29 ± 0.04 a | 18.64 ± 0.66 a | 1.08 ± 0.02 a | 40.83 ± 1.23 b | 0.991 | |

| LL | 13.04 ± 0.14 a | 22.43 ± 0.50 a | 2.29 ± 0.10 a | 19.08 ± 0.36 a | 1.07 ± 0.04 a | 41.25 ± 0.94 b | 0.998 |

| Soil Depth | pH | Organic Content (g kg−1) | Alkali Hydrolyzable Nitrogen Content (mg kg−1) | Available Phosphorus Content (mg kg−1) | Available Potassium Content (mg kg−1) | Total Nitrogen Content (g kg−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–20 | 7.93 | 8.72 | 33.33 | 7.5 | 119.33 | 0.67 |

| 20–40 | 7.92 | 7.49 | 28.14 | 12.53 | 115 | 0.63 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, M.; Zhang, L.; Li, Y.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, Z.; Zhang, D.; Lin, W. Root–Canopy Coordination Drives High Yield and Nitrogen Use Efficiency in Dryland Winter Wheat. Plants 2026, 15, 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010153

Li M, Zhang L, Li Y, Cao Y, Zhang Y, Gao Z, Zhang D, Lin W. Root–Canopy Coordination Drives High Yield and Nitrogen Use Efficiency in Dryland Winter Wheat. Plants. 2026; 15(1):153. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010153

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Meng, Limin Zhang, Yuanxin Li, Yunxuan Cao, Yueran Zhang, Zhiqiang Gao, Dongsheng Zhang, and Wen Lin. 2026. "Root–Canopy Coordination Drives High Yield and Nitrogen Use Efficiency in Dryland Winter Wheat" Plants 15, no. 1: 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010153

APA StyleLi, M., Zhang, L., Li, Y., Cao, Y., Zhang, Y., Gao, Z., Zhang, D., & Lin, W. (2026). Root–Canopy Coordination Drives High Yield and Nitrogen Use Efficiency in Dryland Winter Wheat. Plants, 15(1), 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010153