Plants Utilization and Perceptions in the Context of Novel Indigenous Food Spicing and Flavoring Among the Vhavenḓa People in the Vhembe Biosphere Reserve, South Africa

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

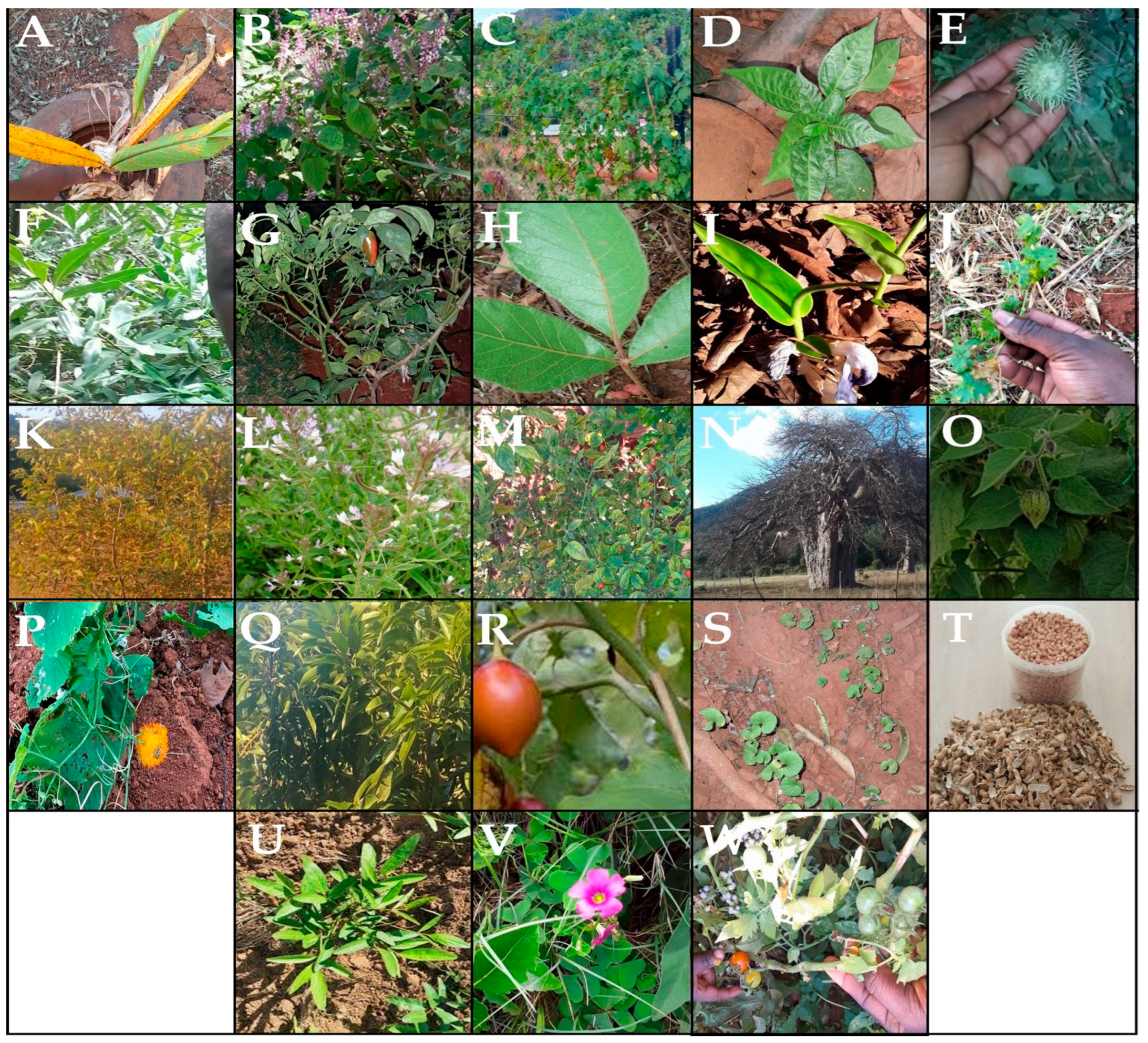

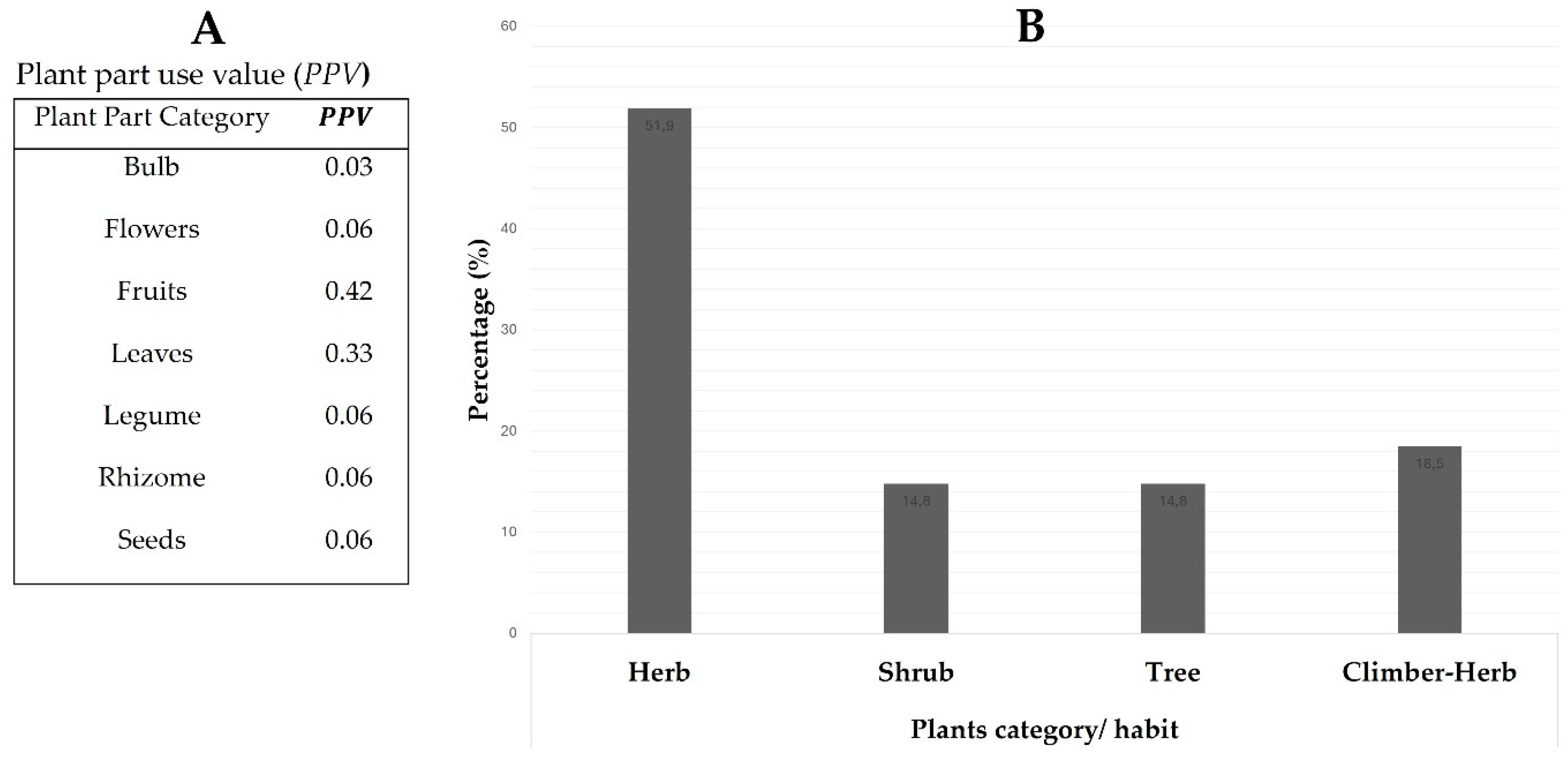

2.1. Taxonomic Diversity of the Utilized Plant Species

2.2. Inventory of Plant Species Used for Spicing or Flavoring Novel Indigenous Venḓa Foods

| Family Name | Species and Voucher Number | Vernacular Venda and English Names | Habit | Used Part | Preparational Recipe | Flavored Food | Similar Use Report | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anacardiaceae | ** Lannea edulis (Sond.) Engl. (MM52/ump/02/24) | Mutshutshungwa (V)/Mutshutshunwa (V)/Wild Grape (E) | Shrub | Fruit | Ripped fresh fruits add aroma and flavor to meat stew and mopane worms. | Mukokoroshi meat stew and mopane worms | 0.27 | 0.15 | 15 | – |

| ** Mangifera indica L. (MM51/ump/02/24) | Munngo (V)/Mango (E) | Tree | Tender seed and leaves | Seeds from fresh tender fruit are chopped into small pieces, dried, and ground together with dried tender leaves to become powder. The powder is then mixed with salt and rough or fine ground powder made from either C. annuum or C. frutescens fruits to develop achar spice. | Mango and vegetable achar | 0.38 | 38 | – | ||

| Apiaceae | ** Centella asiatica (L.) Urb. (MM33/ump/02/24) | Tshikekedzhani (V)/Mukulungwane (V)/Pepperwort (E) | Herb | Leave | Fewer chopped, tender fresh leaves are cooked with other vegetables, mopane worms, and meat stew to spice-flavor and add some aroma. | Vegetables, mopane worms, and any meat | 0.27 | 0.27 | 27 | – |

| Brassicaceae | Cleome monophylla L. (MM44/ump/02/24) | Muṱohoṱoho (V)/Cleome (E) | Herb | Flowers, fruits, and leaves | Fresh flowers and fruits are used to flavor other vegetables. Fresh leaves give the fully cooked meat a nice aroma, while dried ground leaves spice-boiled or fried eggs and meat. | Vegetables, eggs, and any meat | 0.12 | 0.12 | 12 | [37] |

| Canellaceae | ** Warburgia salutaris (G. Bertol.) Chiov. (MM26/ump/02/24) | Mulanga (V)/Fever Tree (E) | Tree | Leaves | Fresh leaves are cooked with either meat stew, mopane worms, or potato meal to add aroma and hot flavor, while chopped dried leaves are ground and used as hot flavoring herbs. | Mukokoroshi meat stew, mopane worms, termites, and potato meal | 0.22 | 0.22 | 22 | – |

| Cucurbitaceae | Cucumis zeyheri Sond. (MM31/ump/02/24) | Tshinyagu (V)/Wild Cucumber (E) | Climber-herb | Leaves | Fresh leaves are used to flavor other vegetables. | Vegetables | 0.89 | 0.36 | 36 | [38] |

| Cucurbita maxima Duchesne (MM29/ump/02/24) | Thanga (V)/Squash (E) | Climber-herb | Tender Fruit | Tender fresh fruit is chopped and cooked together to spice-flavor C. maxima, C. moschata, or C. pepo vegetables. | Vegetables | 1.00 | 100 | [39,40] | ||

| Cucurbita moschata Duchesne (MM32/ump/02/24) | Thanga (V)/Butternut squash (E) | Climber-herb | Fruit | Tender fresh fruit is chopped and cooked together to spice-flavor C. maxima, C. moschata, or C. pepo vegetables. | Vegetables | 1.00 | 100 | [41,42] | ||

| Cucurbita pepo L. (MM30/ump/02/24) | Thanga (V)/Summer squash (E) | Climber-herb | Fruit | Tender fresh fruit is chopped and cooked to spice-flavor C. maxima, C. moschata, or C. pepo vegetables. | Vegetables | 1.00 | 100 | [43,44] | ||

| Momordica balsamina L. (MM28/ump/02/24) | Tshibavhi (V)/Lukake (V)/Balsam apple (E) | Herb | Leaves and fruit | Fresh leaves and fruit are combined with other vegetables to spice-flavor, while dried powdered leaves are used to spice up mopane worms and meat stew. | Vegetables, mopane worms, and mukokoroshi meat stew | 0.98 | 98 | [43] | ||

| Momordica charantia L. (MM27/ump/02/24) | Lugu (V)/Tshibavhe (V)/Bitter squash (E) | Herb | Leaves and fruit | Fresh leaves and fruit are combined with other vegetables to spice-flavor, while dried powdered leaves are used to spice up mopane worms and meat stew. | Vegetables, mopane worms, and any meat stew | 0.89 | 90 | [43] | ||

| Momordica foetida Schumach. (MM34/ump/02/24) | Nngu (V)/Bitter cucumber (E) | Climber-herb | Leaves | Fresh leaves are combined with other vegetables to spice-flavor, while dried powdered leaves are used to spice up mopane worms and meat stew. | Vegetables, mopane worms, and mukokoroshi meat stew | 1.00 | 100 | [43] | ||

| Fabaceae | Arachis hypogaea L. (MM49/ump/02/24) | Nḓuhu (V)/Groundnut (E) | Herb | Legume | Dried legumes are used to flavor and as one of the ingredients of a novel venda meal called Tshidzimba (Venda samp meal). Dried, ground, and powdered legumes are also used to spice vegetables, mopane worms, and meat stew. | Any meat stew, mopane worms, vegetables, and samp meal called Tshidzimba | 0.98 | 1.00 | 100 | [43,44] |

| Vigna subterranea (L.) Verdc. (MM50/ump/02/24) | Phonḓa (V)/Bambara groundnut (E) | Herb | Legume | Dried legumes are cooked as part of the ingredients to flavor and make a samp Venda meal called Tshidzimba. | Samp meal called Tshidzimba | 0.96 | 96 | [43,44] | ||

| Lamiaceae | ** Plectranthus fruticosus L’Hér. (MM38/ump/02/24) | Tshiḓifhisaṋombelo (V)/Muzavhazavha (V)/Liana spur flower (E) | Herb | Leaves | Dried leaves are ground to become rough and used as flavoring herbs. | Any meat, potatoes, eggs, mopane worms, and sweet potatoes | 0.64 | 0.64 | 64 | – |

| Malvaceae | Abelmoschus esculentus (L.) Moench (MM45/ump/02/24) | Delelemandande (V)/Okra (E) | Herb | Fruit | Chopped fresh fruits are used to spice or flavor vegetables and meat stew. Alternatively, chopped fruit can be dried up, ground into fine powder, and used to spice or add flavor to novel food, including meat stew and braai meat. | Vegetable and any meat | 0.57 | 0.97 | 97 | [43] |

| * Adansonia digitata L. (MM46/ump/02/24) | Muvhuyu (V)/Baobab (E) | Tree | Tender leaves, flowers, fruit, and seeds | Tender row leaves are placed into the cooked stew meat and mopane worms to add flavor. Dried flowers, grey-whitish dried fruit, and seed powder are mixed and ground into powder to spice or flavor mopane worms, meat, potatoes, sweet potatoes, or vegetables. Powder is also used to flavor fresh milk. | Mukokoroshi meat stew, mopane worms, potato meal, sweet potatoes, and vegetables | 0.16 | 16 | [44] | ||

| ** Hibiscus sabdariffa subsp. cannabinus L. (MM47/ump/02/24) | Delelemukwayo (V)/Roselle (E) | Herb | Leaves | Dried and powdered leaver add aroma and spice-flavored meat. | Meat | 0.58 | 58 | – | ||

| Oxalidaceae | ** Oxalis semiloba Sond. (MM37/ump/02/24) | Mukulungwane (V)/Common sorrel (E) | Herb | Leaves and bulb | Dried powdered leaves are used to spice up mopane meat stew, mopane worms, mashed potatoes, and sweet potatoes. | Beef meat stew, mopane worms, potatoes, and sweet potatoes | 0.44 | 0.44 | 44 | – |

| Rhamnaceae | ** Ziziphus mucronata subsp. mucronata (MM48/ump/02/24) | Mukhalu (V)/Buffalo thorn (E) | Tree | Fruit | Fruit coats together with mesocarp are separated from the seed, then dried, and therefore ground into fine powder to spice up meat and potatoes. | Meat and potatoes | 0.29 | 0.29 | 29 | – |

| Solanaceae | Capsicum annuum var. annuum (MM39/ump/02/24) | Phiriphiri (V)/Chili pepper (E) | Shrub | Fruit | Chopped fresh fruits or dried ground powder is used to spice up meat, mopane worms, vegetables, and edible stink-bugs. | Vegetables, mopane worms, stink-bug, termites, and any meat | 0.75 | 1.00 | 100 | [22,45] |

| Capsicum frutescens L. (MM42/ump/02/24) | Phiriphiri (V)/Bird pepper (E) | Shrub | Fruit | Chopped fresh fruits or dried ground powder is used to spice up meat, mopane worms, vegetables, and edible stink-bugs. | Vegetables, mopane worms, stink-bugs, termites, and meat | 1.00 | 100 | [45] | ||

| Solanum lycopersicum L. (MM41/ump/02/24) | Muṱamaṱisi (V)/Mukudzungu (V)/Tomato (E) | Herb | Fruit | Chopped ripe fresh fruits are used to spice-flavor vegetables, eggs, potatoes, mopane worms, and meat. | Vegetables, eggs, potatoes, mopane worms, and meat | 1.00 | 100 | [28,46,47] | ||

| ** Physalis peruviana L. (MM40/ump/02/24) | Murunguḓane (V)/Cape gooseberry (E) | Herb | Fruit | Ripped-like-rot fruits are smashed and cooked with brown sugar to produce fruit jam, which is used to spice-flavor the braaied meat. | Braai meat | 0.36 | 36 | – | ||

| Solanum betaceum Cav. (MM43/ump/02/24) | Muṱamaṱisi (V)/Tree tomato (E) | Shrub | Fruit | Fresh fruit is chopped into smaller pieces to spice-flavor vegetable and meat stew. | Vegetables and meat stew | 0.41 | 41 | [48,49,50] | ||

| Zingiberaceae | * Curcuma longa L. (MM35/ump/02/24) | Mukheri (V)/Turmeric (E) | Herb | Rhizome | The chopped, dried, and powdered rhizome is used for spicing meat, potatoes, and potato chips. | Vegetable and meat | 0.24 | 0.21 | 21 | [51,52,53] |

| Siphonochilus aethiopicus (Schweinf.) B.L.Burtt (MM36/ump/02/24) | Dzhinzhaḓaka (V)/Tshirungulu (V)/Wild ginger (E) | Herb | Rhizome | A fresh rhizome is chopped into small pieces and cooked with vegetables, meat stew, or mopane worms to add aromatic flavor. Dried, ground, powdered rhizome is used to spice meat. | Vegetables and meat | 0.27 | 27 | [54,55] |

| Perceptions Category | n = 360 | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Improvement of food taste and nutrition | 155 | 43.1 |

| Provision of medicinal benefits | 120 | 33.3 |

| Fundamental cultural identity | 85 | 23.6 |

2.3. Contribution of Plants Utilized in the Context of Spicing or Flavoring Novel Indigenous Venḓa Foods, as Perceived by Participants

3. Materials and Methods

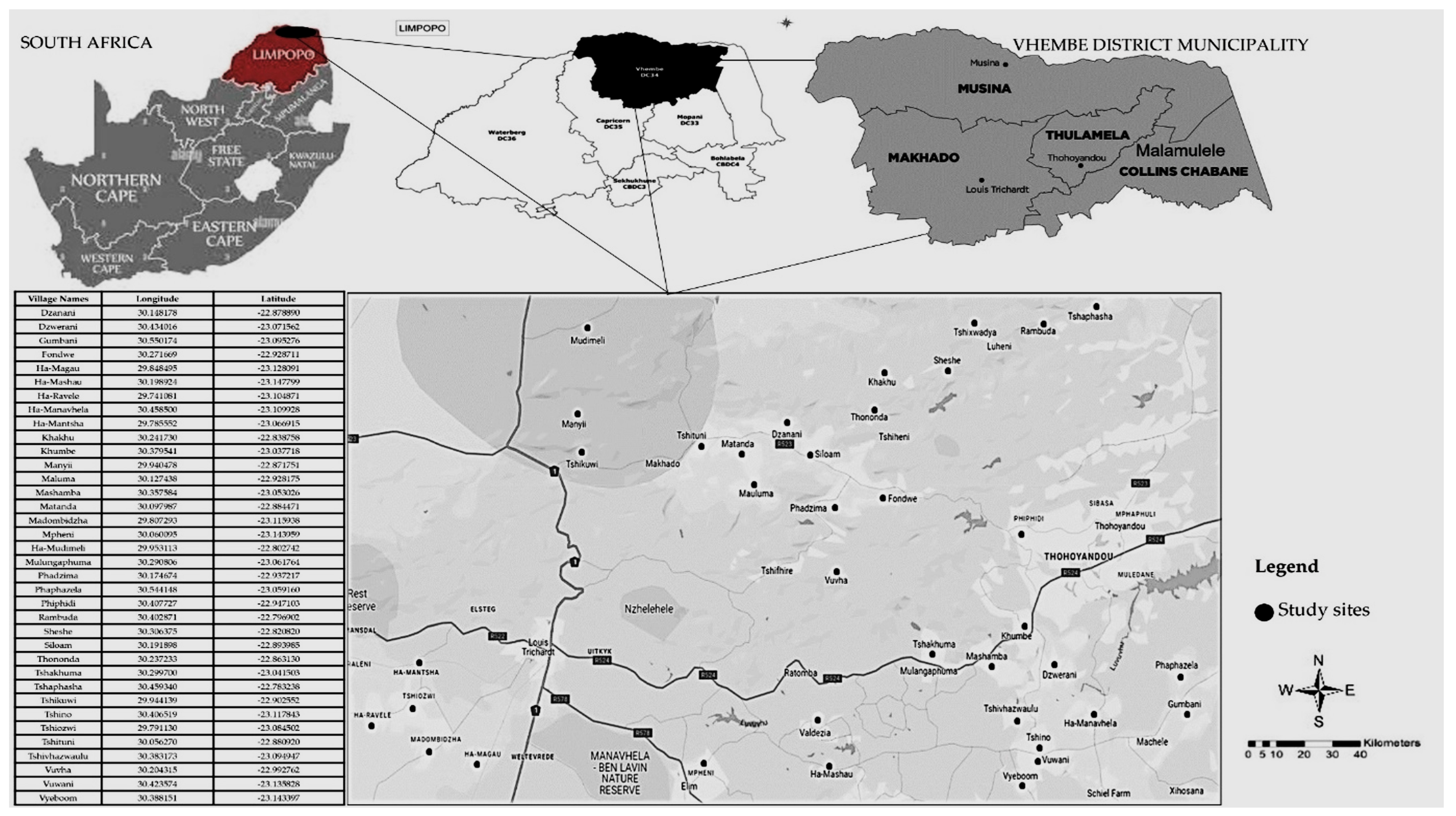

3.1. Study Sites

3.2. Participants’ Demographic Details

3.3. Data Collection and Validation

3.3.1. Phase One: Pilot Survey

3.3.2. Phase Two: Participants and Research Method Selections

- Have you ever cooked indigenous foods?

- If yes, which plant species and parts did you use to flavor your foods, and how did you prepare them?

3.3.3. Phase Three: Data Collection and Authentication

3.3.4. Plant Identification and Ethical Approval

3.3.5. Data Analysis

- (a)

- Family Importance Value (FIV)

- (b)

- Relative Frequency of Citation (RFC)

- (c)

- Fidelity Level Percentage (FL%)

- (d)

- Plant Part Use Value (PPV)

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AGRICERT | Agricultural Certification Body |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| CSIR | Council for Scientific and Industrial Research of South Africa |

| FIV | Family importance value |

| FL% | Fidelity level percentage |

| IPNI | International Plant Name Index |

| NRF | National Research Foundation of South Africa |

| POWO | Plants of the World Online |

| PPV | Plant part use value |

| RFC | Relative frequency of citation |

| SANBI | South African Biodiversity Institute |

References

- Senavirathna, R.M.I.S.K.; Ekanayake, S.; Jansz, E.R. Traditional and novel foods from indigenous flours: Nutritional quality, glycemic response, and potential use in food industry. Starch-Stärke 2016, 68, 999–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asowata-Ayodele, A.M.; Afolayan, A.J.; Otunola, G.A. Ethnobotanical survey of culinary herbs and spices used in the traditional medicinal system of Nkonkobe Municipality, Eastern Cape, South Africa. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2016, 104, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulieman, A.M.E.; Abdallah, E.M.; Alanazi, N.A.; Ed-Dra, A.; Jamal, A.; Idriss, H.; Alshammari, A.S.; Shommo, S.A. Spices as sustainable food preservatives: A comprehensive review of their antimicrobial potential. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Saqqa, G.S. What to know about food flavor? A Review. Jordan J. Agri. Sci. 2022, 18, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Casal, M.N.; Peña-Rosas, J.P.; Malavé, H.G. Sauces, spices, and condiments: Definitions, potential benefits, consumption patterns, and global markets. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2016, 1379, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, S.P.; Wu, Y.C. Spices and Seasonings. In Handbook of Fermented Meat and Poultry, 2nd ed.; Toldrá, F., Hui, Y.H., Astiasarán, I., Sebranek, J.G., Talon, R., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dini, I.; Laneri, S. Spices, condiments, extra virgin olive oil and aromas as not only flavorings, but precious allies for our wellbeing. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmayani, E.; Lestari, L.A.; Sari, P.M.; Gardjito, M. Local Food Diversification and Its (Sustainability) Challenges. In Sustainability Challenges in the Agrofood Sector, R., 1st ed.; Bhat, R., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 119–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Śmiechowska, M.; Newerli-Guz, J.; Skotnicka, M. Spices and Seasoning Mixes in European Union—Innovations and Ensuring Safety. Foods 2021, 10, 2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viuda-Martos, M.; Ruiz-Navajas, Y.; Fernández-López, J.; Pérez-Álvarez, J.A. Spices as functional foods. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2010, 51, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Gupta, A.; Prasad, R. A review on herbs, spices and functional food used in diseases. Int. J. Res. Rev. 2017, 4, 103–108. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M.; Saini, P.; Prasad, K. Spices as a Functional Food for Health. In Functional Foods: Technological Challenges and Advancement in Health Promotion; Wani, S.A., Elshikh, M.S., Al-Wahaibi, M.S., Naik, H.R., Eds.; CRC Press: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 248–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloete, P.C.; Idsardi, E.F. Consumption of indigenous and traditional food crops: Perceptions and realities from South Africa. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2013, 37, 902–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djiazet, S.; Kenfack, L.B.M.; Ngangoum, E.S.; Nzali, H.G.; Tchiegang, C. Indigenous spices consumed in the food habits of the populations living in some countries of Sub-Saharan Africa: Utilisation value, nutritional and health potentials for the development of functional foods and drugs: A review. Food Res. Int. 2022, 157, 111280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdul, M.; Ingabire, A.; Lam, C.Y.N.; Bennett, B.; Menzel, K.; MacKenzie-Shalders, K.; van Herwerden, L. Indigenous food sovereignty assessment—A systematic literature review. Nut. Diet. 2023, 81, 12–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Graciá, C.; González-Bermúdez, C.A.; Cabellero-Valcárcel, A.M.; Santaella-Pascual, M.; Frontela-Saseta, C. Use of herbs and spices for food preservation: Advantages and limitations. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2015, 6, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubisi, N.P.; Ramarumo, L.J.; Manyaga, M.; Mbeng, W.O.; Mokgehle, S. Perceptions on utilization, population, and factors that affecting local distribution of Mimusops zeyheri in the Vhembe Biosphere Reserve, South Africa. J. Biol. Divers. 2023, 24, 6432–6439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grand View Research. Seasoning & Spices Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report by Product (Spices, Herbs, Salt and Salts Substitutes), by Form (Whole, Crushed, Powder), by Distribution Channel, by Region, and Segment Forecasts, 2023–2030. 2024. Available online: https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/seasonings-spices-market# (accessed on 5 March 2024).

- Akinola, R.; Pereira, L.M.; Mabhaudhi, T.; De Bruin, F.M.; Rusch, L. A review of indigenous food crops in Africa and the implications for more sustainable and healthy food systems. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nxusani, Z.N.; Zuma, M.K.; Mbhenyane, X.G. A Systematic Review of Indigenous Food Plant Usage in Southern Africa. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masekoameng, M.R.; Molotja, M.C. The role of indigenous foods and indigenous knowledge systems for rural households’ Food Security in Sekhukhune District, Limpopo Province, South Africa. J. Consum. Sci. 2019, 4, 34–48. [Google Scholar]

- Mokganya, M.G. Documentation and Nutritional Evaluation of Some Wild Edible Fruit Plants and Traditional Vegetable of the Vhembe District Municipality, Limpopo Province, South Africa. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Venda, Thohoyandou, South Africa, 2019. Available online: https://univendspace.univen.ac.za/handle/11602/1613 (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Dawood, Q.; Seedat-Khan, M. The unforgiving work environment of black African women domestic workers in a post-apartheid South Africa. Dev. Pract. 2023, 33, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ujong, A.; Naibaho, J.; Ghalamara, S.; Tiwari, B.K.; Hanon, S.; Tiwari, U. Duckweed: Exploring its farm-to-fork potential for food production and biorefineries. Sustain. Food Technol. 2025, 3, 54–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramarumo, L.J. Harnessing Ecosystem Services from Invasive Alien Grass and Rush Species to Suppress their Aggressive Expansion in South Africa. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGaw, L.J.; Omokhua-Uyi, A.G.; Finnie, J.F.; Van Staden, J. Invasive alien plants and weeds in South Africa: A review of their applications in traditional medicine and potential pharmaceutical properties. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2022, 283, 114564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramarumo, L.J. Threatened Plant Species in Vhembe Biosphere Reserve, Limpopo Province, South Africa: Problems and Prospects of Conservation and Utilization. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Fort Hare, Alice, South Africa, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mokganya, M.G.; Mushaphi, L.F.; Tshisikhawe, M.P. Indigenous preparation and preservation methods of selected indigenous wild edible vegetables of the Vhembe District municipality. Indilinga Afr. J. Indig. Knowl. Syst. 2019, 18, 44–54. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC-173988d82b (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Ekechi, C.C.; Chukwurah, E.G.; Oyeniyi, L.D.; Okeke, C.D. A review of small business growth strategies in African economies. Int. J. Adv. Econ. 2024, 6, 76–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallick, P.K. Evaluating potential importance of cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.-Cucurbitaceae): A brief review. Int. J. Appl. Sci. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 12–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, P.K.; Singha, S.; Kar, A.; Chanda, J.; Banerjee, S.; Dasgupta, B.; Haldar, P.K.; Sharma, N. Therapeutic importance of Cucurbitaceae: A medicinally important family. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2022, 282, 114599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, P.K. Ethnopharmacology and Ethnomedicine-Inspired Drug Development. In Quality Control and Evaluation of Herbal Drugs; Mukherjee, P.K., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 29–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralte, L.; Sailo, H.; Singh, Y.T. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used by the indigenous community of the western region of Mizoram, India. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2024, 20, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, M. Exploring Ethnobotanical Knowledge: Qualitative Insights into the Therapeutic Potential of Medicinal Plants. Gold. Ratio Data Summ. 2024, 4, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oti, H.C.; Offia-Olua, B.I.; Ukom, A.N. Flavour profiles, antioxidant activity, particle size distribution and functional properties of some ethnic spice seed powder used as food additive. Food Chem. Adv. 2024, 5, 100744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J. A Study on Nyonya Food Culture from the Perspective of Cross-Cultural Adaptation Theory. Sci. Soc. Res. 2024, 6, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farapti, F.; Sari, A.N.; Adi, A.C.; Majid, H.B.A. Culinary herbs and spices for low-salt dietary management: Taste sensitivity and preference among the elderly. NFS J. 2024, 34, 100162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkumar, T.R.; Karuppusamy, S. Plant Diversity and Ethnobotanical Knowledge of Spices and Condiments. In Bioprospecting of Plant Biodiversity for Industrial Molecules; Upadhyay, S.K., Singh, S.P., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, Chapter 12; pp. 231–260. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Van Wyk, B.E. The potential of South African plants in the development of new food and beverage products. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2011, 77, 857–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlJahani, A.; Cheikhousman, R. Nutritional and sensory evaluation of pumpkin-based (Cucurbita maxima) functional juice. Nutr. Food Sci. 2017, 47, 346–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akintade, A.O.; Ifesan, B.O.; Awolu, O.O.; Olaleye, T.M. Evaluation of physicochemical properties and sensory attributes of pumpkin seed (Cucurbita maxima) bouillon cube. J. Culin. Sci. Technol. 2024, 22, 1272–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benites, J.F.; Gutiérrez, D.R.; Ruiz, S.C.; Rodriguez, S.D.C. February. Influence of the Application of Rosemary Essential Oil (Salvia rosmarinus) on the Sensory Characteristics and Microbiological Quality of Minimally Processed Pumpkin (Cucurbita moschata). Biol. Life Sci. Forum 2025, 40, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoy, J.M.; Hamid, M.A.; Ayub, M.S.; Suratman, R.; Effendi, M.M. Development of Food Seasoning using Sub-standard Fish Cracker, Pumpkin (Cucurbita moschata) and Seaweed (Kappaphycus alvarezii). IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2025, 1446, 012031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokganya, M.G.; Tshisikhawe, M.P. Medicinal uses of selected wild edible vegetables consumed by Vhavenda of the Vhembe District Municipality, South Africa. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2019, 122, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molapisi, M.; Tselaesele, N.; Makhabu, S.; Bultosa, G.; Haki, G.D.; Kobue-Lekalake, R.; Sekwati-Monang, B.; Seifu, E.; Phakama, T. Plant-based traditional foods of Mogoditshane, Mmopane and Metsimotlhabe villages, Botswana: Nutritional and bioactive compounds potential, processing, values, and challenges. Discov. Food 2024, 4, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, R.; Cheng, L.; Yu, S.; Nie, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, J.Q.; Pan, C.; Zhu, W.; Diao, J.; et al. Improvement by application of three nanomaterials on flavor quality and physiological and antioxidant properties of tomato and their comparison. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2023, 201, 107834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umeohia, U.E.; Olapade, A.A. Quality attributes, physiology, and Postharvest Technologies of Tomatoes (Lycopersicum esculentum)—A review. Am. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 12, 42–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antala, P.A.; Chakote, A.; Varshney, N.; Suthar, K.; Singh, D.; Narwade, A.; Patel, K.; Gandhi, K.; Singh, S.; Karmakar, N. Phytochemical and metabolic changes associated with ripening of Lycopersicon esculentum. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 10692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Kilmartin, P.A.; Fedrizzi, B.; Quek, S.Y. Elucidation of endogenous aroma compounds in tamarillo (Solanum betaceum) using a molecular sensory approach. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 9362–9375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isla, M.I.; Orqueda, M.E.; Moreno, M.A.; Torres, S.; Zampini, I.C. Solanum betaceum Fruits Waste: A Valuable Source of Bioactive Compounds to Be Used in Foods and Non-Foods Applications. Foods 2022, 11, 3363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machado, A.M.R.; Teodoro, A.J.; Mariutti, L.R.B.; da Fonseca, J.C.N. Tamarillo (Solanum betaceum Cav.) wastes and by-products: Bioactive composition and health benefits. Heliyon 2024, 10, e37600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibáñez, M.D.; Blázquez, M.A. Curcuma longa L. rhizome essential oil from extraction to its agri-food applications. A review. Plants 2020, 10, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güneri, N. A review on turmeric (Curcuma longa L.) and usage in seafood. Mar. Sci Technol. Bull. 2021, 10, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Wei, B.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, T.; Yu, J.; Xue, Y.; Kong, B.; Xue, C.; Tang, Q. Multifunctional curcumin/γ-cyclodextrin/sodium chloride complex: A strategy for salt reduction, flavor enhancement, and antimicrobial activity in low-sodium foods. LWT 2024, 213, 117085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes-Ríos, D.; Ortigosa, A.; Quiñonero, F.; Melguizo, C.; Ortiz, R.; Prados, J.; Díaz, A.; López-Romero, J.M. Isolation and Antitumoral Effect of a New Siphonochilone Derivative from African Ginger. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 15718–15722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortigosa-Palomo, A.; Fuentes-Ríos, D.; Quiñonero, F.; Melguizo, C.; Ortiz, R.; López-Romero, J.M.; Prados, J. Evaluation of cytotoxic effect of siphonochilone from African ginger: An in vitro analysis. Environ. Toxicol. 2024, 39, 4333–4346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahrajabian, M.H.; Sun, W. The golden spice for life: Turmeric with the pharmacological benefits of curcuminoids components, including curcumin, bisdemethoxycurcumin, and demethoxycurcumins. Curr. Org. Synth. 2024, 21, 665–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, J.; Kaur, P.; Chuwa, C. Nutritional benefits of herbs and spices to the human beings. Ann. Phytomed. Int. J. 2023, 12, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maqbool, M.; Chaudhary, K.; Chalotra, R.; Chauhan, S.; Dahiya, R.S. Phyto-pharmacology of most common Indian culinary spices and their potential in developing new pharmaceutical therapies. Curr. Tradit. Med. 2024, 10, 117–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.; Chong, S.C. How do people perceive the variability of multifeature objects? J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 2025, 51, 202–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mucina, L.; Rutherford, M.C. The Vegetation of South Africa, Lesotho and Swaziland. Strelitzia 19; South African National Biodiversity Institute: Pretoria, South Africa, 2006; pp. 2–801. [Google Scholar]

- Mpandeli, S. Managing climate risks using seasonal climate forecast information in Vhembe District in Limpopo Province, South Africa. J. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 7, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, N. An historic account of the extinct high rainfall grasslands of the Soutpansberg, South Africa. Trans. R. Soc. S. Afr. 2018, 73, 20–32. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC-c60bb4ca4 (accessed on 27 December 2024). [CrossRef]

- Mostert, T.H.; Bredenkamp, G.J.; Klopper, H.L.; Verwey, C. Major vegetation types of the Soutpansberg conservancy and the Blouberg Nature Reserve, South Africa. Koedoe 2008, 50, 32–48. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC139700 (accessed on 27 December 2024). [CrossRef]

- Nyimbili, F.; Nyimbili, L. Types of Purposive Sampling Techniques with Their Examples and Application in Qualitative Research Studies. Br. J. Multidisc. Adv. Stud. 2024, 5, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, J.R.; Baptiste, S.; Bhattacharjee, P.; Cowan, F.M.; Herce, M.E.; Lauer, K.; Sikazwe, I.; Geng, E. Programme science methodologies and practices that address “FURRIE” challenges: Examples from the field. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2024, 27, e26283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Damme, L.; Chatrou, L.; de la Peña, E.; Kibungu, P.; Bolya, C.S.; Van Damme, P.; Vanhove, W.; Ceuterick, M.; De Meyer, E. Plant use and perceptions in the context of sexual health among people of Congolese descent in Belgium. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2024, 20, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magwede, K.; Van Wyk, B.E.; Van Wyk, A.E. An inventory of Vhavenḓa useful plants. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2019, 122, 57–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabogo, D.E.N. The Ethnobotany of the Vhavenda. Master’s Thesis, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- SANBI, Red List of South African Plants. Available online: http://redlist.sanbi.org/ (accessed on 26 June 2024).

- IPNI. International Plant Names Index. Available online: https://www.ipni.org/ (accessed on 26 June 2024).

- POWO. Plants of the World Online. Available online: https://powo.science.kew.org/ (accessed on 26 June 2024).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, M.; Ankli, A.; Frei, B.; Weimann, C.; Sticher, O. Medicinal plants in Mexico: Healers’ consensus and cultural importance. Soc. Sci. Med. 1998, 47, 1859–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez-Beloz, A. Plant use knowledge of the Winikina Warao: The case for questionnaires in ethnobotany. Econ. Bot. 2002, 56, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hachlafi, N.; Chebat, A.; Bencheikh, R.S.; Fa, K. Ethnopharmacological study of medicinal plants used for the treatment of chronic diseases in the Rabat-Sale-Kenitra region (Morocco). Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 2020, 20, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Anova: Single Factor | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Groups | Count | Sum | Average | Variance | F | p-Value |

| Improvement of food taste and nutrition | 3 | 203 | 67,666 | 380,333 | 11,057 | 0.009 |

| Provision of medicinal benefits | 3 | 106 | 35,333 | 136,333 | ||

| Fundamental cultural identity | 3 | 51 | 17 | 19 | ||

| Gender | No. of Participants | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 137 | 38.06 |

| Female | 223 | 61.94 |

| Age in years | ||

| Age > 36 < 48 years old | 203 | 56.39 |

| Age > 48 < 60 years old | 106 | 29.44 |

| Age > 60 < 72 years old | 51 | 14.17 |

| Educational background | ||

| No formal education | 39 | 10.83 |

| Primary education | 109 | 30.28 |

| Secondary education | 179 | 49.72 |

| Tertiary education | 33 | 9.17 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Manyaga, M.; Mhlongo, N.P.; Matlala, M.E.; Lubisi, N.P.; Gelebe, V.; Mkhonto, C.; Kola, E.; Mbeng, W.O.; Ndhlovu, P.T.; Mokgehle, S.N.; et al. Plants Utilization and Perceptions in the Context of Novel Indigenous Food Spicing and Flavoring Among the Vhavenḓa People in the Vhembe Biosphere Reserve, South Africa. Plants 2025, 14, 1962. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14131962

Manyaga M, Mhlongo NP, Matlala ME, Lubisi NP, Gelebe V, Mkhonto C, Kola E, Mbeng WO, Ndhlovu PT, Mokgehle SN, et al. Plants Utilization and Perceptions in the Context of Novel Indigenous Food Spicing and Flavoring Among the Vhavenḓa People in the Vhembe Biosphere Reserve, South Africa. Plants. 2025; 14(13):1962. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14131962

Chicago/Turabian StyleManyaga, Mueletshedzi, Ncobile Pretty Mhlongo, Maropeng Erica Matlala, Nonhlanhla Prudence Lubisi, Vhuhwavho Gelebe, Christeldah Mkhonto, Elizabeth Kola, Wilfred Otang Mbeng, Peter Tshepiso Ndhlovu, Salmina Ngoakoana Mokgehle, and et al. 2025. "Plants Utilization and Perceptions in the Context of Novel Indigenous Food Spicing and Flavoring Among the Vhavenḓa People in the Vhembe Biosphere Reserve, South Africa" Plants 14, no. 13: 1962. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14131962

APA StyleManyaga, M., Mhlongo, N. P., Matlala, M. E., Lubisi, N. P., Gelebe, V., Mkhonto, C., Kola, E., Mbeng, W. O., Ndhlovu, P. T., Mokgehle, S. N., Matlanyane, M. M., Liuvha, N., Dlamini, N. R., & Ramarumo, L. J. (2025). Plants Utilization and Perceptions in the Context of Novel Indigenous Food Spicing and Flavoring Among the Vhavenḓa People in the Vhembe Biosphere Reserve, South Africa. Plants, 14(13), 1962. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14131962