Molecular Cloning and Expression Profile of Class E Genes Related to Sepal Development in Nelumbo nucifera

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Materials

2.2. Total RNA Extraction and cDNA Synthesis

2.3. Gene Clone and Sequence Identification

2.4. Sequence Analysis

2.5. Subcellular Localization

2.6. Gene Expression Analysis

2.7. Yeast Two-Hybrid (Y2H) Assay

3. Results

3.1. Cloning of the Full-Length cDNA of the SEP Gene

3.2. Analysis of Physicochemical Properties of Proteins

3.3. Secondary and Tertiary Structures of Proteins

3.4. Phylogenetic Analysis of NnSEP1, NnAGL9 and NnMADS6-Like Proteins

3.5. Subcellular Localization of NnSEP1, NnAGL9 and NnMADS6-Like Proteins

3.6. Expression Pattern Analysis of NnSEP1, NnAGL9 and NnMADS6-like Genes

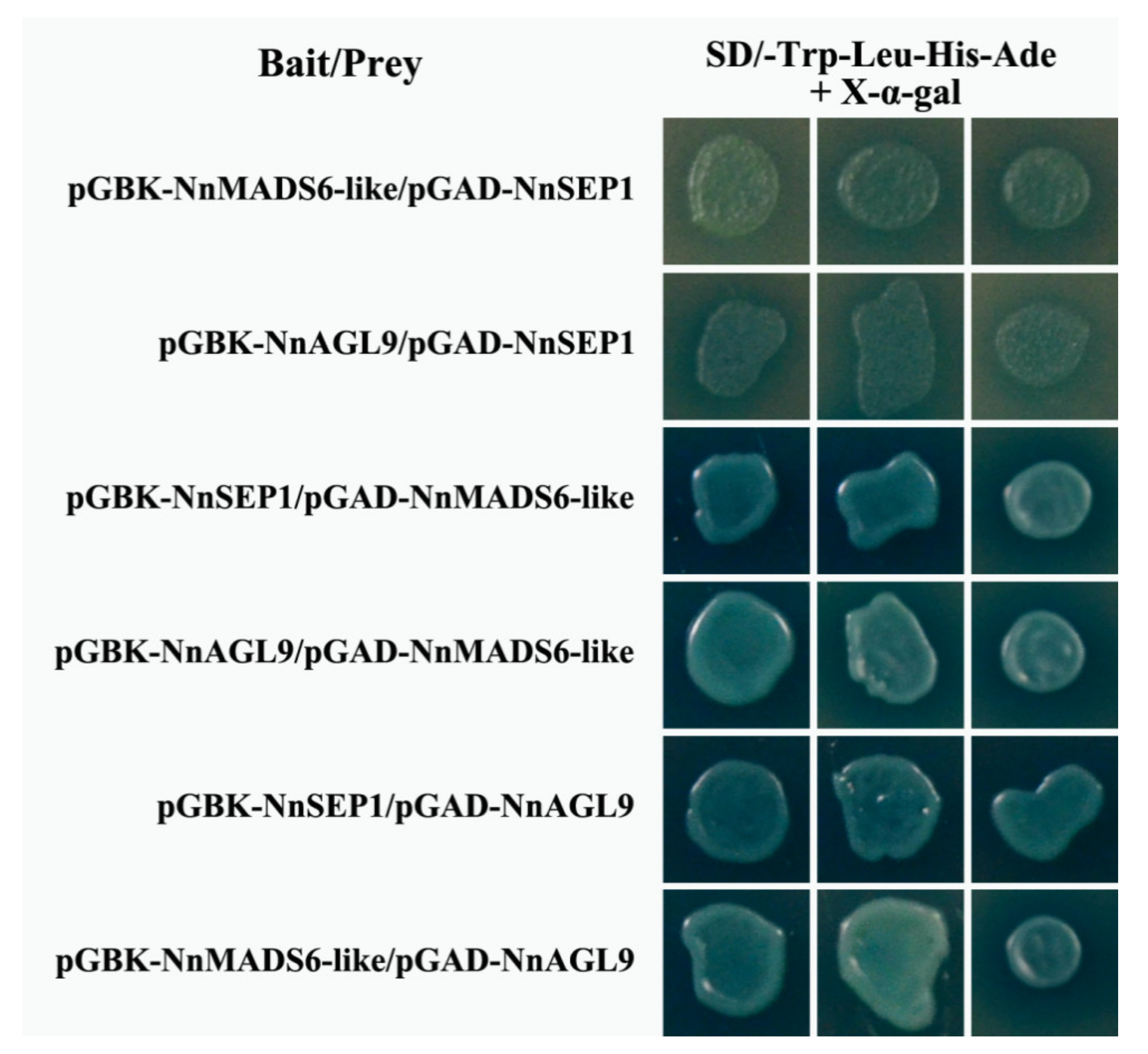

3.7. Protein Interaction Between NnSEP1, NnMADS6-Like and NnAGL9

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bowman, J.L.; Smyth, D.R.; Meyerowitz, E.M. The ABC model of flower development: Then and now. Development 2012, 139, 4095–4098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Norman, C.; Runswick, M.; Pollock, R.; Treisman, R. Isolation and properties of cDNA clones encoding SRF, a transcription factor that binds to the c-fos serum response element. Cell 1988, 55, 989–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passmore, S.; Maine, G.T.; Elble, R.; Christ, C.; Tye, B.K. Saccharomyces cerevisiae protein involved in plasmid maintenance is necessary for mating of MAT alpha cells. J. Mol. Biol. 1988, 204, 593–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, H.; Beltran, J.P.; Huijser, P.; Pape, H.; Lonnig, W.E.; Saedler, H.; Schwarz-Sommer, Z. Deficiens, a homeotic gene involved in the control of flower morphogenesis in Antirrhinum majus: The protein shows homology to transcription factors. EMBO J. 1990, 9, 605–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez-Buylla, E.R.; Pelaz, S.; Liljegren, S.J.; Gold, S.E.; Burgeff, C.; Ditta, G.S.; Ribas-de Pouplana, L.; Martinez-Castilla, L.; Yanofsky, M.F. An ancestral MADS-box gene duplication occurred before the divergence of plants and animals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 5328–5333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Parenicova, L.; de Folter, S.; Kieffer, M.; Horner, D.S.; Favalli, C.; Busscher, J.; Cook, H.E.; Ingram, R.M.; Kater, M.M.; Davies, B.; et al. Molecular and phylogenetic analyses of the complete MADS-box transcription factor family in Arabidopsis: New openings to the MADS world. Plant Cell 2003, 15, 1538–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alvarez-Buylla, E.R.; Liljegren, S.J.; Pelaz, S.; Gold, S.E.; Burgeff, C.; Ditta, G.S.; Vergara-Silva, F.; Yanofsky, M.F. MADS-box gene evolution beyond flowers: Expression in pollen, endosperm, guard cells, roots and trichomes. Plant J. 2000, 24, 457–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Forde, B.G. An Arabidopsis MADS box gene that controls nutrient-induced changes in root architecture. Science 1998, 279, 407–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Xu, G.L.; Chi, Y.J.; Liu, H.C.; Xue, Q.; Zhao, T.J.; Gai, J.Y.; Yu, D.Y. A soybean MADS-box protein modulates floral organ numbers, petal identity and sterility. BMC Plant Biol. 2014, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pelucchi, N.; Fornara, F.; Favalli, C.; Masiero, S.; Lago, C.; Pe, M.E.; Colombo, L.; Kater, M.M. Comparative analysis of rice MADS-box genes expressed during flower development. Sex. Plant Reprod. 2002, 15, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Hu, L.F.; Song, J.B.; Jiang, L.W.; Liu, S.Q. Isolation and characterization of a MADS-box gene in cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) that affects flowering time and leaf morphology in transgenic Arabidopsis. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2019, 33, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vandenbussche, M.; Zethof, J.; Souer, E.; Koes, R.; Tornielli, G.B.; Pezzotti, M.; Ferrario, S.; Angenent, G.C.; Gerats, T. Toward the analysis of the petunia MADS box gene family by reverse and forward transposon insertion mutagenesis approaches: B, C, and D floral organ identity functions require SEPALLATA-like MADS box genes in Petunia. Plant Cell 2003, 15, 2680–2693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Seymour, G.B.; Ryder, C.D.; Cevik, V.; Hammond, J.P.; Popovich, A.; King, G.J.; Vrebalov, J.; Giovannoni, J.J.; Manning, K. A SEPALLATA gene is involved in the development and ripening of strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa Duch.) fruit, a non-climacteric tissue. J. Exp. Bot. 2011, 62, 1179–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coen, E.S.; Meyerowitz, E.M. The war of the whorls: Genetic interactions controlling flower development. Nature 1991, 353, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles, P.; Pelaz, S. Flower and fruit development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2005, 49, 633–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smaczniak, C.; Immink, R.G.H.; Muino, J.M.; Blanvillain, R.; Busscher, M.; Busscher-Lange, J.; Dinh, Q.D.; Liu, S.J.; Westphal, A.H.; Boeren, S.; et al. Characterization of MADS-domain transcription factor complexes in Arabidopsis flower development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 1560–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Theissen, G.; Saedler, H. Plant biology. Floral quartets. Nature 2001, 409, 469–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honma, T.; Goto, K. Complexes of MADS-box proteins are sufficient to convert leaves into floral organs. Nature 2001, 409, 525–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelaz, S.; Ditta, G.S.; Baumann, E.; Wisman, E.; Yanofsky, M.F. B and C floral organ identity functions require SEPALLATA MADS-box genes. Nature 2000, 405, 200–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, A.R.; Malcomber, S.T. Duplication and diversification of the LEAFY HULL STERILE1 and Oryza sativa MADS5 SEPALLATA lineages in graminoid Poales. Evodevo 2012, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nishikawa, F.; Endo, T.; Shimada, T.; Fujii, H.; Shimizu, T.; Kobayashi, Y.; Araki, T.; Omura, M. Transcriptional changes in CiFT-introduced transgenic trifoliate orange (Poncirus trifoliata L. Raf.). Tree Physiol. 2010, 30, 431–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, S.S.; Lu, S.J.; Yi, S.S.; Han, H.J.; Liu, L.; Zhang, J.Q.; Bao, M.Z.; Liu, G.F. Functional conservation and divergence of five SEPALLATA-like genes from a basal eudicot tree, Platanus acerifolia. Planta 2017, 245, 439–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, G.; Yang, C.H.; Shen, C.Y.; Huang, K.S. Origination and selection of ABCDE and AGL6 subfamily MADS-box genes in gymnosperms and angiosperms. Biol. Res. 2019, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melzer, R.; Wang, Y.Q.; Theissen, G. The naked and the dead: The ABCs of gymnosperm reproduction and the origin of the angiosperm flower. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2010, 21, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morel, P.; Chambrier, P.; Boltz, V.; Chamot, S.; Rozier, F.; Bento, S.R.; Trehin, C.; Monniaux, M.; Zethof, J.; Vandenbussche, M. Divergent functional diversification patterns in the SEP/AGL6/AP1 MADS-Box transcription factor superclade. Plant Cell 2019, 31, 3033–3056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rijpkema, A.S.; Zethof, J.; Gerats, T.; Vandenbussche, M. The petunia AGL6 gene has a SEPALLATA-like function in floral patterning. Plant J. 2009, 60, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.H.; Yan, T.X.; Shen, Q.; Lu, X.; Pan, Q.F.; Huang, Y.R.; Tang, Y.L.; Fu, X.Q.; Liu, M.; Jiang, W.M.; et al. Glandular trichome-specific wrky 1 promotes artemisinin biosynthesis in Artemisia annua. New Phytol. 2017, 214, 304–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.J.; Hao, X.Y.; Liang, Z.S.; Ke, W.D.; Guo, H.B. Efficient isolation of high-quality RNA from lotus Nelumbo nucifera ssp. nucifera tissues. Genet. Mol. Res. 2013, 12, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.B.; Lian, H.L.; Xu, F.; Zhang, T.; Wang, S.; Wang, W.X.; Du, S.S.; Huang, J.R.; Yang, H.Q. Phytochrome B and AGB1 coordinately regulate photomorphogenesis by antagonistically modulating PIF3 stability in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant. 2019, 12, 229–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saitou, N.; Nei, M. The neighbor-joining method-a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1987, 4, 406–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Nei, M. Estimation of the number of nucleotide substitutions in the control region of mitochondrial-dna in humans and chimpanzees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1993, 10, 512–526. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Thompson, J.D.; Higgins, D.G.; Gibson, T.J. Clustal-W improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994, 22, 4673–4680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lin, Z.Y.; Damaris, R.N.; Shi, T.; Li, J.J.; Yang, P.F. Transcriptomic analysis identifies the key genes involved in stamen petaloid in lotus (Nelumbo nucifera). BMC Genom. 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lin, Z.Y.; Liu, M.; Damaris, R.N.; Nyong’a, T.M.; Cao, D.D.; Ou, K.F.; Yang, P.F. Genome-Wide DNA methylation profiling in the lotus (Nelumbo nucifera) flower showing its contribution to the stamen petaloid. Plants 2019, 8, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Flanagan, C.A.; Ma, H. Spatially and temporally regulated expression of the MADS-box gene AGL2 in wild-type and mutant Arabidopsis flowers. Plant Mol. Biol. 1994, 26, 581–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Yanofsky, M.F.; Meyerowitz, E.M. AGL1-AGL6, an Arabidopsis gene family with similarity to floral homeotic and transcription factor genes. Genes Dev. 1991, 5, 484–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rounsley, S.D.; Ditta, G.S.; Yanofsky, M.F. Diverse roles for MADS box genes in Arabidopsis development. Plant Cell 1995, 7, 1259–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Endress, P.K. Evolutionary diversificatin of the flowers in angiosperms. Am. J. Bot. 2011, 98, 370–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ohmori, S.; Kimizu, M.; Sugita, M.; Miyao, A.; Hirochika, H.; Uchida, E.; Nagato, Y.; Yoshida, H. Mosaic floral organs1, an AGL6-like MADS box gene, regulates floral organ identity and meristem fate in rice. Plant Cell 2009, 21, 3008–3025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, L.S.; Chen, F.; Zhang, X.T.; Li, Z.; Zhao, Y.Y.; Lohaus, R.; Chang, X.J.; Dong, W.; Ho, S.Y.W.; Liu, X.; et al. The water lily genome and the early evolution of flowering plants. Nature 2020, 577, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Immink, R.G.H.; Tonaco, I.A.N.; de Folter, S.; Shchennikova, A.; van Dijk, A.D.J.; Busscher-Lange, J.; Borst, J.W.; Angenent, G.C. SEPALLATA3: The ‘glue’ for MADS box transcription factor complex formation. Genome Biol. 2009, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jetha, K.; Theissen, G.; Melzer, R. Arabidopsis SEPALLATA proteins differ in cooperative DNA-binding during the formation of floral quartet-like complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, 10927–10942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Melzer, R.; Theissen, G. Reconstitution of floral quartets in vitro involving class B and class E floral homeotic proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, 2723–2736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pajoro, A.; Madrigal, P.; Muino, J.M.; Tomas Matus, J.; Jin, J.; Mecchia, M.A.; Debernardi, J.M.; Palatnik, J.F.; Balazadeh, S.; Arif, M.; et al. Dynamics of chromatin accessibility and gene regulation by MADS-domain transcription factors in flower development. Genome Biol. 2014, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malcomber, S.T.; Kellogg, E.A. SEPALLATA gene diversification: Brave new whorls. Trends Plant Sci. 2005, 10, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Primer Name | Sequence (5′→3′) |

|---|---|

| AP | GGCCACGCGTCGACTAGTACTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTT |

| AUAP | GTACTAGTCGACGCGTGGCC |

| NnSEP1-full-F | ATGGGGAGAGGAAGGGTAGA |

| NnSEP1-RT-F | GGAAGCTGGATGAAAGTAGT |

| NnSEP1-RT-R | AAGCATCCACCCAGGAATAT |

| NnAGL9-RT-F | AGGGAGTCAGAGGAGCTGAG |

| NnAGL9-RT-R | CAATGCCCTGTTAGCTTCGC |

| NnMADS6-like-RT-F | AGCTAGGCAACGGAAGACAC |

| NnMADS6-like-RT-R | TCCCTCCGGTGGAACATAGT |

| NnActin-F | ACCACTGCTGAACGGGAAAT |

| NnActin-R | ATGGCTGGAATAGAACCTCA |

| 1300-NnSEP1-GFP-F | GGATCCATGGGGAGAGGAAGGGTAGA |

| 1300-NnSEP1-GFP-R | TCTAGAAAGCATCCACCCAGGAA |

| 1300-Nn AGL9-GFP-F | GGATCCATGGGGAGAGGTAGGGTTGA |

| 1300-Nn AGL9-GFP-R | TCTAGATGCCAGCCACCCAGGC |

| 1300-NnMADS6-like-GFP-F | GGATCCATGGGAAGAGGACGAGTAGA |

| 1300-NnMADS6-like-GFP-R | TCTAGAGAGAACCCATCCTTGAAT |

| AD-NnSEP1-F | CATATGGGGAGAGGAAGGGTAGAGCTGAA |

| AD-NnSEP1-R | GGATCCCAAGCATCCACCCAGGAATATAACCATT |

| AD-NnAGL9-F | CATATGGGGAGAGGAAGGGTAGAGCTGAA |

| AD-NnAGL9-R | GGATCCCTGCCAGCCACCCAGGCATATAACTA |

| AD-NnMADS6-like-F | CATATGGGGAGAGGAAGGGTAGAGCTG |

| AD-NnMADS6-like-R | GGATCCCGAGAACCCATCCTTGAATGAAGTTA |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, Z.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, W.; Xiong, L.; Liu, Q.; Liu, F.; Li, H.; An, X.; Cui, L.; Tian, D. Molecular Cloning and Expression Profile of Class E Genes Related to Sepal Development in Nelumbo nucifera. Plants 2021, 10, 1629. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10081629

Liu Z, Zhang D, Zhang W, Xiong L, Liu Q, Liu F, Li H, An X, Cui L, Tian D. Molecular Cloning and Expression Profile of Class E Genes Related to Sepal Development in Nelumbo nucifera. Plants. 2021; 10(8):1629. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10081629

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Zhuoxing, Dasheng Zhang, Weiwei Zhang, Lei Xiong, Qingqing Liu, Fengluan Liu, Hanchun Li, Xiangjie An, Lijie Cui, and Daike Tian. 2021. "Molecular Cloning and Expression Profile of Class E Genes Related to Sepal Development in Nelumbo nucifera" Plants 10, no. 8: 1629. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10081629

APA StyleLiu, Z., Zhang, D., Zhang, W., Xiong, L., Liu, Q., Liu, F., Li, H., An, X., Cui, L., & Tian, D. (2021). Molecular Cloning and Expression Profile of Class E Genes Related to Sepal Development in Nelumbo nucifera. Plants, 10(8), 1629. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10081629