The Interplay of One-Carbon Metabolism, Mitochondrial Function, and Developmental Programming in Ruminant Livestock

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Developmental Programming

3. Maternal Nutrition as a Key Regulator of Fetal Development

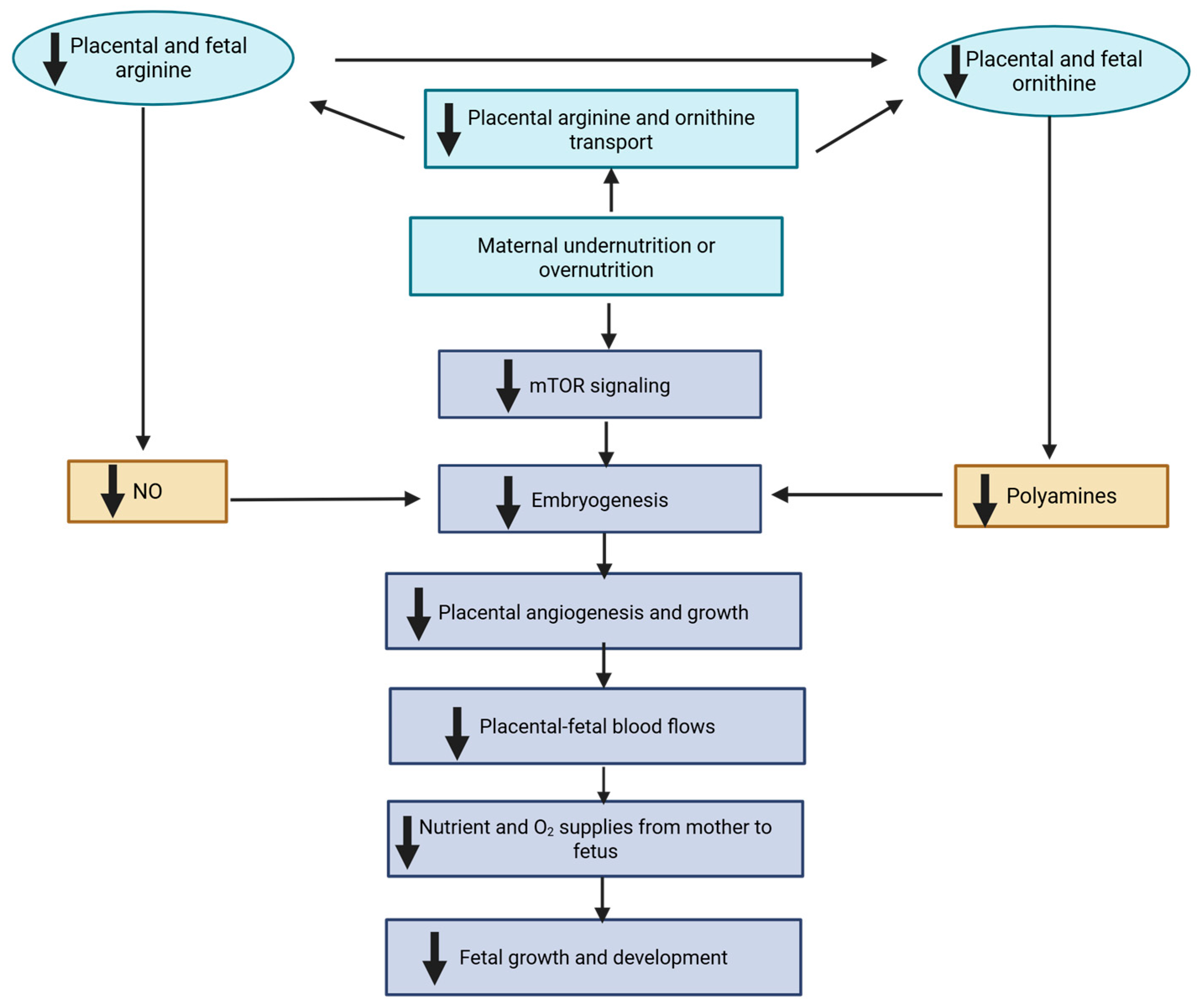

3.1. Consequences of Nutrient Deficiency or Imbalance

3.2. Timing of Nutritional Alterations Matter

3.3. Livestock-Specific Challenges

4. One-Carbon Metabolism and Its Role in Fetal Development

4.1. Importance for Methylation and Cell Growth

4.2. One-Carbon Nutrient Supplementation Studies in Livestock Throughout Gestation

5. Mitochondrial Function in Fetal Development and Programming

6. Metabolomics as a Tool to Study Fetal Development

7. Integrated Mito-Metabolomics Perspective in Maternal-Fetal Research

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vickers, M.H. Early life nutrition, epigenetics and programming of later life disease. Nutrients 2014, 6, 2165–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, D. Nutrition in early life: How important is it? Clin. Perinatol. 2002, 29, 203–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabory, A.; Attig, L.; Junien, C. Developmental programming and epigenetics. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 94, S1943–S1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenwood, P.L.; Bell, A.W. Consequences of nutrition during gestation, and the challenge to better understand and enhance livestock productivity and efficiency in pastoral ecosystems. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2014, 54, 1109–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, J.; Gustafson, K.M.; Carlson, S.E. Critical and sensitive periods in development and nutrition. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2019, 75, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Bazer, F.W.; Cross, H.R. Land-based production of animal protein: Impacts, efficiency, and sustainability. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2014, 1328, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, L.P.; Caton, J.S.; Redmer, D.A.; Grazul-Bilska, A.T.; Vonnahme, K.A.; Borowicz, P.P.; Ward, J.; Taylor, J.B. Importance of animals in agricultural sustainability and food security. J. Nutr. 2015, 145, 1377–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, G.A.D.; da Silva, L.F.A.; Oguejiofor, C.F.; Balico-Silva, A.L.; Chagas, L.M.; de Moraes, G.V.; Pontes, J.H.F.; Mapletoft, R.J. Fetal developmental programing: Insights from human studies and experimental models. J. Matern.-Fetal Neonatal Med. 2017, 30, 722–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, P.L.; Slepetis, R.M.; Bell, A.W. Influences on fetal and placental weights during mid to late gestation in prolific ewes well nourished throughout pregnancy. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 2000, 12, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makiabadi, M.J.M.; Dadashpour Davachi, N.; Mirzaei, A.; Jalili, M.; Seifi, H.A. Developmental programming of production and reproduction in dairy cows: II. Association of gestational stage of maternal exposure to heat stress with offspring’s birth weight, milk yield, reproductive performance and AMH concentration during the first lactation period. Theriogenology 2023, 212, 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Otomaru, K.; Oshima, K.; Goto, Y.; Oshima, I.; Muroya, S.; Sano, M.; Roh, S.; Gotoh, T. Maternal nutrition during gestation alters histochemical properties, and mRNA and microRNA expression in adipose tissue of Wagyu fetuses. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 12, 797680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradis, F.; Wood, K.M.; Swanson, K.C.; Miller, S.P.; McBride, B.W. Maternal nutrient restriction in mid-to-late gestation influences fetal mRNA expression in muscle tissues in beef cattle. BMC Genom. 2017, 18, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diniz, W.J.S.; Reynolds, L.P.; Ward, A.K.; Caton, J.S.; Dahlen, C.R.; McCarthy, K.L.; Menezes, A.C.B.; Cushman, R.A.; Crouse, M.S. Epigenetics and nutrition: Molecular mechanisms and tissue adaptation in developmental programming. In Molecular Mechanisms in Nutritional Epigenetics; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 49–69. [Google Scholar]

- Friso, S.; Udali, S.; De Santis, D.; Choi, S.W. One-carbon metabolism and epigenetics. Mol. Asp. Med. 2017, 54, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casanova, A.; dos Santos, C.V.; Lima, M.H.S.; Oliveira, M.L.M.; da Silva, D.H.; de Oliveira, H.C.F. Mitochondria: It is all about energy. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1114231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, S. Emerging insights into the metabolic alterations in aging using metabolomics. Metabolites 2019, 9, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, D.J. The developmental origins of well–being. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2004, 359, 1359–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piro, E.; Giordano, D.; La Placa, S.; Schimmenti, M.G.; Corsello, G. Fetal growth restriction: A growth pattern with fetal, neonatal and long-term consequences. Eur. Biomed. J. 2019, 14, 038–044. [Google Scholar]

- Bazer, F.W.; Johnson, G.A.; Wu, G.; Bayless, K.; Wallace, J.M.; Spencer, T.E. Maternal nutrition and fetal development. J. Nutr. 2004, 134, 2169–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, P.; Hunt, A.; Hermanson, J.; Bell, A.W. Effects of birth weight and postnatal nutrition on neonatal sheep: II. Skeletal muscle growth and development. J. Anim. Sci. 2000, 78, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, K.; Burns, G.; Spencer, T.E. Conceptus elongation in ruminants: Roles of progesterone, prostaglandin, interferon tau and cortisol. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2014, 5, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazer, F.W.; Wu, G.; Johnson, G.A.; Kim, J.; Song, G. Uterine histotroph and conceptus development: Select nutrients and secreted phosphoprotein 1 affect mechanistic target of rapamycin cell signaling in ewes. Biol. Reprod. 2011, 85, 1094–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, N.E.; Abrams, B.; Barbour, L.A.; Catalano, P.M.; Christian, P.; Friedman, J.E.; Hay, W.W.; Hernandez, T.L.; Krebs, N.F.; Rasmussen, K.M.; et al. The importance of nutrition in pregnancy and lactation: Lifelong consequences. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 226, 607–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwachukwu, C. Nutritional effects on fetal development during gestation in ruminants. Niger. J. Anim. Prod. 2020, 47, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A. The Effects of Poor Maternal Nutrition on Offspring Growth and Maternal and Offspring Inflammatory Status During Gestation. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fowden, A.L.; Giussani, D.A.; Forhead, A.J. Intrauterine programming of physiological systems: Causes and consequences. Physiology 2006, 21, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gernand, A.D.; Schulze, K.J.; Stewart, C.P.; West, K.P.; Christian, P. Micronutrient deficiencies in pregnancy worldwide: Health effects and prevention. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2016, 12, 274–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koblinsky, M.A. Beyond maternal mortality—Magnitude, interrelationship and consequences of women's health, pregnancy-related complications and nutritional status on pregnancy outcomes. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 1995, 48, S21–S32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansson, T.; Powell, T.L. Human placental transport in altered fetal growth: Does the placenta function as a nutrient sensor?–a review. Placenta 2006, 27, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caton, J.; Hess, B. Maternal plane of nutrition: Impacts on fetal outcomes and postnatal offspring responses. In Proceedings of the 4th Grazing Livestock Nutrition Conference, Estes Park, CO, USA, 9–10 July 2010; American Society of Animal Science: Champaign, IL, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Redmer, D.A.; Wallace, J.M.; Reynolds, L.P. Effect of nutrient intake during pregnancy on fetal and placental growth and vascular development. Domest. Anim. Endocrinol. 2004, 27, 199–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reed, J.J.; Ward, M.A.; Vonnahme, K.A.; Soto-Navarro, S.A.; Hallford, D.M.; Redmer, D.A.; Reynolds, L.P.; Caton, J.S. Effects of selenium supply and dietary restriction on maternal and fetal body weight, visceral organ mass and cellularity estimates, and jejunal vascularity in pregnant ewe lambs. J. Anim. Sci. 2007, 85, 2721–2733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vonnahme, K.A.; Lemley, C.O.; Shukla, P.; O’Rourke, S.T. Impacts of maternal nutrition on vascularity of nutrient transferring tissues during gestation and lactation. Nutrients 2015, 7, 3497–3523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, D.L.; Cafe, L.M.; McKiernan, W.A. Heritability of muscle score and genetic and phenotypic relationships with weight, fatness and eye muscle area in beef cattle. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2014, 54, 1443–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcondes, M.I.; Ferreira, R.M.A.; Paulino, M.F.; Machado, F.S.; Oliveira, S.C.; Detmann, E. Protein requirements for pregnant dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2023, 106, 8821–8834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larson, D.M.; Martin, J.L.; Adams, D.C.; Funston, R.N. Winter grazing system and supplementation during late gestation influence performance of beef cows and steer progeny. J. Anim. Sci. 2009, 87, 1147–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stalker, L.A.; Adams, D.C.; Klopfenstein, T.J.; Feuz, D.M.; Funston, R.N. Effects of pre-and postpartum nutrition on reproduction in spring calving cows and calf feedlot performance. J. Anim. Sci. 2006, 84, 2582–2589. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, L.P.; Caton, J.S. Role of the pre-and post-natal environment in developmental programming of health and productivity. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2012, 354, 54–59. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, D.L.; Cafe, L.M.; Greenwood, P.L. Meat science and muscle biology symposium: Developmental programming in cattle: Consequences for growth, efficiency, carcass, muscle, and beef quality characteristics. J. Anim. Sci. 2013, 91, 1428–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, T.J.; Hammer, C.J.; Luther, J.S.; Carlson, D.B.; Taylor, J.B.; Redmer, D.A.; Reynolds, L.P.; Caton, J.S. Effects of gestational plane of nutrition and selenium supplementation on mammary development and colostrum quality in pregnant ewe lambs. J. Anim. Sci. 2008, 86, 2415–2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace, J.M.; Bourke, D.A.; Aitken, R.P. Nutrition and fetal growth: Paradoxical effects in the overnourished adolescent sheep. J. Reprod. Fertil. Suppl. 1999, 54, 385–399. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood, P.L.; Hunt, A.S.; Hermanson, J.W.; Bell, A.W. Effects of birth weight and postnatal nutrition on neonatal sheep: I. Body growth and composition, and some aspects of energetic efficiency. J. Anim. Sci. 1998, 76, 2354–2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funston, R.N.; Summers, A.F.; Roberts, A.J. Alpharma Beef Cattle Nutrition Symposium: Implications of nutritional management for beef cow-calf systems. J. Anim. Sci. 2012, 90, 2301–2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, J.M.; Milne, J.S.; Aitken, R.P. Postnatal hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal function in sheep is influenced by age and sex, but not by prenatal growth restriction. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 2011, 23, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuzaki, M.; Milne, J.S.; Aitken, R.P.; Wallace, J.M. Overnourishing pregnant adolescent ewes preserves perirenal fat deposition in their growth-restricted fetuses. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 2006, 18, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, J.M.; Aitken, R.P.; Cheyne, M.A.; Humblot, P. Influence of progesterone supplementation during the first third of pregnancy on fetal and placental growth in overnourished adolescent ewes. Reproduction 2003, 126, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.J.; Ma, Y.; Long, N.M.; Du, M.; Ford, S.P. Maternal obesity markedly increases placental fatty acid transporter expression and fetal blood triglycerides at midgestation in the ewe. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2010, 299, R1224–R1231. [Google Scholar]

- Muhlhausler, B.S.; Duffield, J.A.; McMillen, I.C. Increased maternal nutrition stimulates peroxisome proliferator activated receptor-γ, adiponectin, and leptin messenger ribonucleic acid expression in adipose tissue before birth. Endocrinology 2007, 148, 878–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, X.; Zhu, M.J.; Dodson, M.V.; Du, M. Developmental programming of fetal skeletal muscle and adipose tissue development. J. Genom. 2013, 1, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.L.; Vonnahme, K.A.; Adams, D.C.; Lardy, G.P.; Funston, R.N. Effects of dam nutrition on growth and reproductive performance of heifer calves. J. Anim. Sci. 2007, 85, 841–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, A.M.; Caton, J.S. Role of the small intestine in developmental programming: Impact of maternal nutrition on the dam and offspring. Adv. Nutr. 2016, 7, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, G.J.; Lewis, R.M.; Jauniaux, E.R.M. Placental anatomy and physiology. In Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies, 9th ed.; Gabbe, S.G., Niebyl, J.R., Simpson, J.L., Landon, M.B., Galan, H.L., Jauniaux, E.R.M., Driscoll, D.A., Berghella, V., Grobman, W.A., Eds.; Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2016; pp. 2–17. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, H.; Zhang, M.; Yang, J.; Liu, H.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Z.; Liu, H.; Su, R.; Zhang, Y. Modulation of PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway in the ovine liver and duodenum during early pregnancy. Domest. Anim. Endocrinol. 2024, 89, 106870. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, S.P.; Hess, B.W.; Schwope, M.M.; Nijland, M.J.; Gilbert, J.S.; Vonnahme, K.A.; Means, W.J.; Han, H.; Nathanielsz, P.W. Maternal undernutrition during early to mid-gestation in the ewe results in altered growth, adiposity, and glucose tolerance in male offspring. J. Anim. Sci. 2007, 85, 1285–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, E.; Hafner, H.; Varma, K.; Gaire, T.N.; Bakaysa, D.L.; Kumar, S. Programming effects of maternal and gestational obesity on offspring metabolism and metabolic inflammation. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 16027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dancause, K.N.; Laplante, D.P.; Fraser, S.; Brunet, A.; Ciampi, A.; Schmitz, N.; King, S. Prenatal exposure to a natural disaster increases risk for obesity in 5½-year-old children. Pediatr. Res. 2012, 71, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.I.; Odhiambo, J.F.; Henningson, J.N.; Parr, A.; Rhoads, R.P.; McFadden, J.W. Mid-to late-gestational maternal nutrient restriction followed by realimentation alters development and lipid composition of liver and skeletal muscles in ovine fetuses. J. Anim. Sci. 2021, 99, skab299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, L.P.; Redmer, D.A. Expression of the angiogenic factors, basic fibroblast growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor, in the ovary. J. Anim. Sci. 1998, 76, 1671–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, L.P.; Redmer, D.A. Angiogenesis in the placenta. Biol. Reprod. 2001, 64, 1033–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, A.W. Regulation of organic nutrient metabolism during transition from late pregnancy to early lactation. J. Anim. Sci. 1995, 73, 2804–2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynolds, L.P.; Ward, A.K.; Caton, J.S. Epigenetics and developmental programming in ruminants: Long-term impacts on growth and development. In Biology of Domestic Animals; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017; pp. 85–121. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, L.P.; Borowicz, P.P.; Vonnahme, K.A.; Johnson, M.L.; Grazul-Bilska, A.T.; Redmer, D.A.; Caton, J.S. Developmental programming: The concept, large animal models, and the key role of uteroplacental vascular development. J. Anim. Sci. 2010, 88, E61–E72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Funston, R.N.; Larson, D.M.; Vonnahme, K.A. Effects of maternal nutrition on conceptus growth and offspring performance: Implications for beef cattle production. J. Anim. Sci. 2010, 88, E205–E215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouse, M.S.; Ward, A.K.; Dahlen, C.R.; Reynolds, L.P.; Caton, J.S. International Symposium on Ruminant Physiology: One-carbon metabolism in beef cattle throughout the production cycle. J. Dairy Sci. 2024, 108, 7615–7630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clare, C.E.; Brassington, A.H.; Kwong, W.Y.; Sinclair, K.D. One-carbon metabolism: Linking nutritional biochemistry to epigenetic programming of long-term development. Annu. Rev. Anim. Biosci. 2019, 7, 263–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safain, K.S.; Ward, A.K.; Dahlen, C.R.; Reynolds, L.P.; Caton, J.S.; Crouse, M.S. One-carbon metabolites supplementation and nutrient restriction alter the fetal liver metabolomic profile during early gestation in beef heifers. J. Anim. Sci. 2024, 102, skae258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steane, S.E.; Cuffe, J.S.M.; Moritz, K.M. The role of maternal choline, folate and one-carbon metabolism in mediating the impact of prenatal alcohol exposure on placental and fetal development. J. Physiol. 2023, 601, 1061–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, D.N.; Vailati-Riboni, M.; Kennedy, A.; Zhang, F.; Loor, J.J. Multifaceted role of one-carbon metabolism on immunometabolic control and growth during pregnancy, lactation and the neonatal period in dairy cattle. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2021, 12, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alenad, A. The Role of DNA Methyltransferases in Fetal Programming. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Southampton, Southampton, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Averill-Bates, D.A. The antioxidant glutathione. In Vitamins Horm; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; Volume 112, pp. 109–141. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, J.; Mai, C.T.; Mulinare, J.; Isenburg, J.; Flood, T.J.; Ethen, M.; Frohnert, B.; Kirby, R.S. Updated estimates of neural tube defects prevented by mandatory folic acid fortification—United States, 1995–2011. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2015, 64, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Selhub, J.; Rosenberg, I.H. Excessive folic acid intake and relation to adverse health outcome. Biochimie 2016, 126, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, G.L.; Kodell, R.L.; Moore, S.R.; Cooney, C.A. Maternal epigenetics and methyl supplements affect agouti gene expression in Avy/a mice. FASEB J. 1998, 12, 949–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waterland, R.A.; Jirtle, R.L. Transposable elements: Targets for early nutritional effects on epigenetic gene regulation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003, 23, 5293–5300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez-Salas, P.; Moore, S.E.; Cole, D.; da Costa, K.A.; Cox, S.E.; Dyer, R.A.; Fulford, A.J.; Innis, S.M.; Waterland, R.A.; Prentice, A.M. Maternal nutrition at conception modulates DNA methylation of human metastable epialleles. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clare, C.E. One-Carbon Metabolism and Epigenetic Programming of Mammalian Development. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Stover, P.J. One-carbon metabolism–genome interactions in folate-associated pathologies. J. Nutr. 2009, 139, 2402–2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, D.; Pate, R.T.; Clark, J.A.; Loor, J.J. Rumen-protected methionine during heat stress alters mTOR, insulin signaling, and 1-carbon metabolism protein abundance in liver, and whole-blood transsulfuration pathway genes in Holstein cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2022, 105, 7787–7804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouse, M.S.; Pruski, M.L.; Borowicz, P.P.; Reynolds, L.P.; Caton, J.S. Epigenetic modifier supplementation improves mitochondrial respiration and growth rates and alters DNA methylation of bovine embryonic fibroblast cells cultured in divergent energy supply. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 812764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chavatte-Palmer, P.; Tarrade, A.; Rousseau-Ralliard, D. Epigenetics, developmental programming and nutrition in herbivores. Animal 2018, 12, s363–s371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syring, J.G.; Crouse, M.S.; Dahlen, C.R.; Reynolds, L.P.; Caton, J.S. One-carbon metabolite supplementation increases vitamin B12, folate, and methionine cycle metabolites in beef heifers and fetuses in an energy dependent manner at day 63 of gestation. J. Anim. Sci. 2024, 102, skae202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daneshi, M.; Syring, J.G.; Dahlen, C.R.; Reynolds, L.P.; Caton, J.S.; Crouse, M.S. Influence of Maternal Nutrition and One-Carbon Metabolites Supplementation during Early Pregnancy on Bovine Fetal Small Intestine Vascularity and Cell Proliferation. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouse, M.S.; Ward, A.K.; McLean, K.J.; Dahlen, C.R.; Reynolds, L.P.; Caton, J.S. Moderate nutrient restriction of beef heifers alters expression of genes associated with tissue metabolism, accretion, and function in fetal liver, muscle, and cerebrum by day 50 of gestation. Transl. Anim. Sci. 2019, 3, 855–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, L.; Crouse, M.S.; Dahlen, C.R.; Reynolds, L.P.; Caton, J.S. 180 Supplementation of One-Carbon Metabolites to Beef Heifers During Early Gestation Increases Fetal Organ Weight at Day 63 of Gestation. J. Anim. Sci. 2022, 100, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouvêa, V.N.; Pate, R.T.; Feitosa, F.L.B.; Loor, J.J.; Piccioli-Cappelli, F.; Silva, T.H.; Silva, F.F.; Valadares Filho, S.C.; Rotta, P.P. Methionine supply during mid-gestation modulates the bovine placental mTOR pathway, nutrient transporters, and offspring birth weight in a sex-specific manner. J. Anim. Sci. 2024, 102, skae305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, E.A.; Paulino, P.V.R.; Coleman, D.N.; Camp, R.S.; Domenech, K.I.; Farias, N.A.R.; Cooke, R.F.; Vasconcelos, J.T. Maternal supplement type and methionine hydroxy analogue fortification effects on performance of Bos indicus-influenced beef cows and their offspring. Livest. Sci. 2020, 240, 104176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redifer, C.A.; Wichman, L.G.; Meyer, A.M. 70 Nutrient Restriction During Late Gestation Alters Maternal Circulating Amino Acid Concentrations in Primiparous Beef Females. J. Anim. Sci. 2023, 101, 204–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palombo, V.; Coleman, D.N.; Loor, J.J.; Nelson, C.D.; Latham, K.E. Unique adaptations in neonatal hepatic transcriptome, nutrient signaling, and one-carbon metabolism in response to feeding ethyl cellulose rumen-protected methionine during late-gestation in Holstein cows. BMC Genom. 2021, 22, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redifer, C.A.; Wichman, L.G.; Meyer, A.M. Evaluation of peripartum supplementation of methionine hydroxy analogue on beef cow–calf performance. Transl. Anim. Sci. 2023, 7, txad046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waterman, R.C.; Lardy, G.P.; Caton, J.S.; Soto-Navarro, S.A.; Roberts, A.J.; Adams, D.C. Supplemental methionine and urea for gestating beef cows consuming low quality forage diets. J. Anim. Sci. 2007, 85, 731–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safain, K.S.; Crouse, M.S.; Dahlen, C.R.; Reynolds, L.P.; Caton, J.S. Tissue-specific mitochondrial functionality and mitochondrial-related gene profiles in response to maternal nutrition and one-carbon metabolite supplementation during early pregnancy in heifers. Animals 2025, 15, 2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandel, N.S. Evolution of mitochondria as signaling organelles. Cell Metab. 2015, 22, 204–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Z.; Ristow, M. Mitochondria and metabolic homeostasis. In Future Medicine; Mary Ann Liebert, Inc.: New Rochelle, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 240–242. [Google Scholar]

- Lane, N. Mitonuclear match: Optimizing fitness and fertility over generations drives ageing within generations. Bioessays 2011, 33, 860–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pendleton, A.L.; Whitfield, B.R.; Long, N.M.; Ford, S.P.; Nathanielsz, P.W.; Nijland, M.J. Dimming the powerhouse: Mitochondrial dysfunction in the liver and skeletal muscle of intrauterine growth restricted fetuses. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 612888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.K.; Pena, G.; Long, N.M.; Ford, S.P.; Nathanielsz, P.W.; Nijland, M.J. Differential effects of intrauterine growth restriction and a hyperinsulinemic-isoglycemic clamp on metabolic pathways and insulin action in the fetal liver. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2019, 316, R427–R440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muroya, S.; Zhang, Y.; Otomaru, K.; Oshima, K.; Oshima, I.; Sano, M.; Roh, S.; Ojima, K.; Gotoh, T. Maternal nutrient restriction disrupts gene expression and metabolites associated with urea cycle, steroid synthesis, glucose homeostasis, and glucuronidation in fetal calf liver. Metabolites 2022, 12, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saben, J.L.; Boudoures, A.L.; Asghar, Z.; Thompson, A.; Drury, A.; Zhang, W.; Chi, M.; Cusumano, A.; Scheaffer, S.; Moley, K.H. Maternal metabolic syndrome programs mitochondrial dysfunction via germline changes across three generations. Cell Rep. 2016, 16, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudzińska, E.; Kowalski, J.; Bartosiewicz, B.; Kowalska, A.; Wawrzyniak, R.; Cibor, D.; Walkowiak, J. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Reduced TCA Cycle Metabolite Levels in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients. J. Inflamm. Res. 2025, 18, 5205–5216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Shen, L. Advances and trends in omics technology development. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 911861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrova, B.; Mihaylova, E.; Kalaydjieva, L.; Dimitrov, R. Regulatory mechanisms of one-carbon metabolism enzymes. J. Biol. Chem. 2023, 299, 105457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, B.B.; Langefeld, C.D.; Olivier, M.; Cox, L.A. Integrated omics: Tools, advances and future approaches. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2019, 62, R21–R45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Meng, Y.; Han, J. Emerging roles of mitochondrial functions and epigenetic changes in the modulation of stem cell fate. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2024, 81, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.I.; Vásquez-Hidalgo, M.A.; Li, X.; Vonnahme, K.A.; Grazul-Bilska, A.T.; Swanson, K.C.; Moore, T.E.; Reed, S.A.; Govoni, K.E. The Effects of Maternal Nutrient Restriction during Mid to Late Gestation with Realimentation on Fetal Metabolic Profiles in the Liver, Skeletal Muscle, and Blood in Sheep. Metabolites 2024, 14, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, T.J.; Osei-Hyiaman, D.; Page, R.L.; O’Brien, W.D.; Rivera, R.M.; Stiles, J.K.; Kim, E.; Fisher, A.L. Diet-induced obesity alters the maternal metabolome and early placenta transcriptome and decreases placenta vascularity in the mouse. Biol. Reprod. 2018, 98, 795–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Reyes, I.; Chandel, N.S. Mitochondrial TCA cycle metabolites control physiology and disease. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthubharathi, B.C.; Gowripriya, T.; Balamurugan, K. Metabolomics: Small molecules that matter more. Mol. Omics 2021, 17, 210–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, M.; Guo, L. Mitochondrial DNA methylation: State-of-the-art in molecular mechanisms and disease implications. J. Adv. Res. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menezes, A.C.B.; Moreira, G.R.; Santos, D.O.; Souza, F.D.A.; Bonilha, S.F.M.; Cardoso, M.T.; Machado, F.S. Fetal Hepatic Lipidome Is More Greatly Affected by Maternal Rate of Gain Compared with Vitamin and Mineral Supplementation at Day 83 of Gestation. Metabolites 2023, 13, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crouse, M.S.; Borowicz, P.P.; Dahlen, C.R.; Reynolds, L.P.; Caton, J.S. Vitamin and mineral supplementation and rate of weight gain during the first trimester of gestation in beef heifers alters the fetal liver amino acid, carbohydrate, and energy profile at day 83 of gestation. Metabolites 2022, 12, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schalch Junior, F.J.; Dias, D.M.; Barbero, M.M.; Silva, M.C.; Oliveira, R.L.; Marcondes, M.I. Prenatal supplementation in beef cattle and its effects on plasma metabolome of dams and calves. Metabolites 2022, 12, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safain, K.S.; Crouse, M.S.; Dahlen, C.R.; Reynolds, L.P.; Caton, J.S. Early gestational hepatic lipidomic profiles are modulated by one-carbon metabolite supplementation and nutrient restriction in beef heifers and fetuses. Metabolites 2025, 15, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phomvisith, O.; Muroya, S.; Otomaru, K.; Oshima, K.; Oshima, I.; Nishino, D.; Haginouchi, T.; Gotoh, T. Maternal undernutrition affects fetal thymus DNA methylation, gene expression, and, thereby, metabolism and immunopoiesis in Wagyu (Japanese black) cattle. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muroya, S.; Ojima, K.; Shimamoto, S.; Sugasawa, T.; Gotoh, T. Promoter H3K4me3 and Gene Expression Involved in Systemic Metabolism Are Altered in Fetal Calf Liver of Nutrient-Restricted Dams. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caton, J.S.; Crouse, M.S.; Dahlen, C.R.; Ward, A.K.; Diniz, W.J.; Hammer, C.J.; Swanson, R.M.; Hauxwell, K.M.; Syring, J.G.; Safain, K.S.; et al. International Symposium on Ruminant Physiology: Maternal nutrient supply—Impacts on physiological and whole-animal outcomes in offspring. J. Dairy Sci. 2025, 108, 7696–7709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kivelä, J.; Paldánius, P.M.; Sebert, S.; Eriksson, J.G.; Hämäläinen, E.; Laivuori, H. Longitudinal metabolic profiling of maternal obesity, gestational diabetes, and hypertensive pregnancy disorders. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 106, e4372–e4388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermick, J.; Holland, C.; Agarwal, D.; Koenig, J.M. Chorioamnionitis exposure remodels the unique histone modification landscape of neonatal monocytes and alters the expression of immune pathway genes. FEBS J. 2019, 286, 82–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermick, J.R.; Holbrook, J.; Koenig, J.M. Neonatal monocytes exhibit a unique histone modification landscape. Clin. Epigenet. 2016, 8, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, T.; Sun, J.; He, Z.; Zhang, D.; Xu, G. Transcriptome analysis of compensatory growth and meat quality alteration after varied restricted feeding conditions in beef cattle. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imaz, J.A.; García, S.; González, L.A. The metabolomics profile of growth rate in grazing beef cattle. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 2554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Safain, K.S.; Swanson, K.C.; Caton, J.S. The Interplay of One-Carbon Metabolism, Mitochondrial Function, and Developmental Programming in Ruminant Livestock. J. Dev. Biol. 2026, 14, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/jdb14010003

Safain KS, Swanson KC, Caton JS. The Interplay of One-Carbon Metabolism, Mitochondrial Function, and Developmental Programming in Ruminant Livestock. Journal of Developmental Biology. 2026; 14(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/jdb14010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleSafain, Kazi Sarjana, Kendall C. Swanson, and Joel S. Caton. 2026. "The Interplay of One-Carbon Metabolism, Mitochondrial Function, and Developmental Programming in Ruminant Livestock" Journal of Developmental Biology 14, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/jdb14010003

APA StyleSafain, K. S., Swanson, K. C., & Caton, J. S. (2026). The Interplay of One-Carbon Metabolism, Mitochondrial Function, and Developmental Programming in Ruminant Livestock. Journal of Developmental Biology, 14(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/jdb14010003