Planar Cell Polarity Signaling: Coordinated Crosstalk for Cell Orientation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Historical Notes

3. Molecular/Cellular Mechanisms—PCP Signaling Pathway

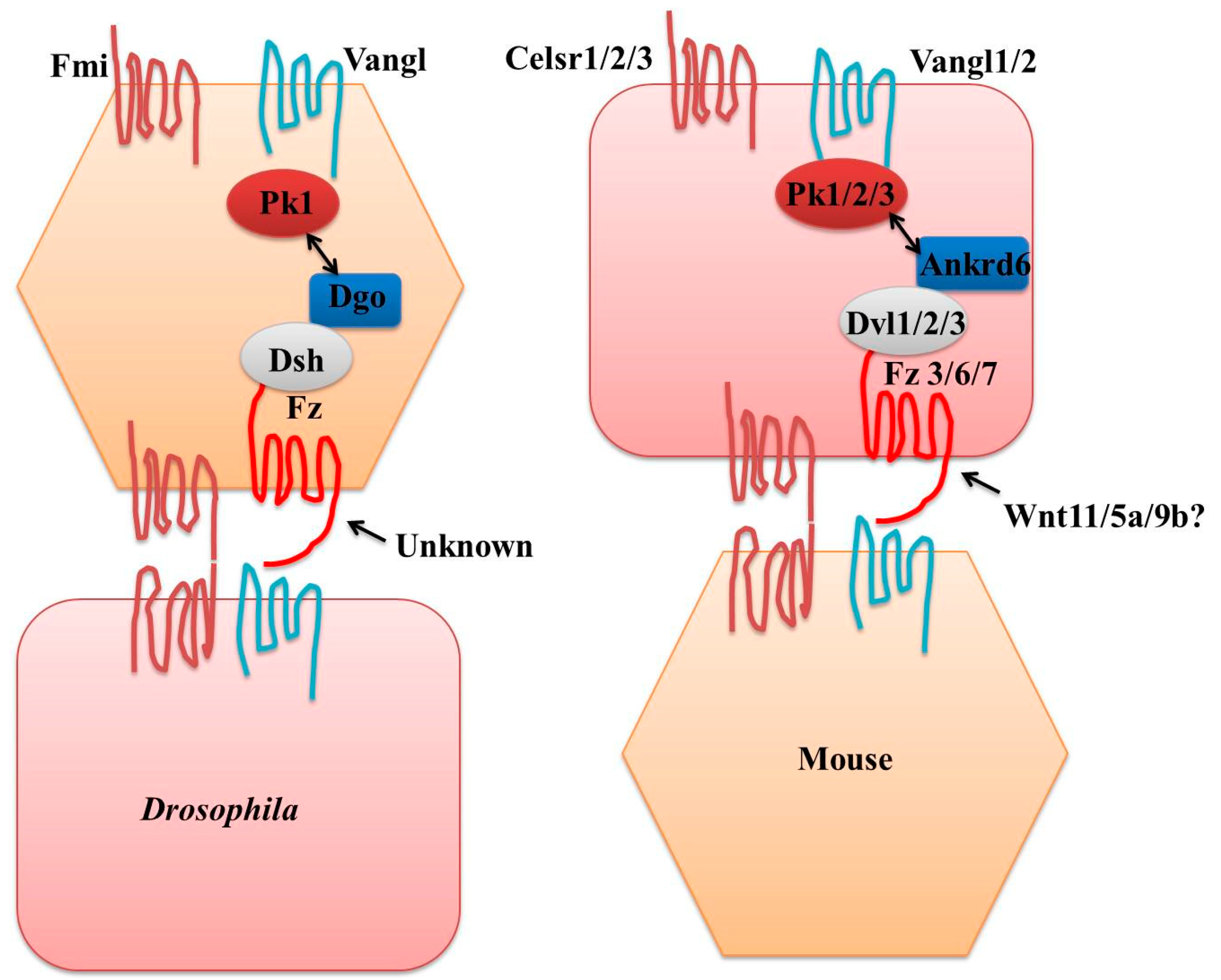

4. Core Components

5. PCP Complex

6. Role of Cell Adhesion Molecules

7. Tissue Morphogenesis—Planar Cell Polarity

8. Neural Tube Closure

9. Tissue Regeneration

10. Developmental Process

- (i)

- Convergent Extension Process: It is the first process that is found to be associated with PCP [56]. MSCs stretch and produce mediolateral protrusions during the convergent extension process. These protrusions incorporate mediolaterally, restricting the mediolateral axis and lengthening the AP axis (Figure 3) [101]. Depletion of PCP components has been linked to mediolateral intercalation, polarization, and elongation, according to several experimental findings [54,56,59,102]. Only two discoveries provide direct mechanistic links between convergent extension behaviors and asymmetrically localized core components of PCP, even though many PCP-dependent mechanisms have been hypothesized to mediate convergent extension movements. On the A-P sites of intercalating cells in neuro-epithelial cells, PCP determines the region of myosin localization. Dvl and Fmi/Celsr1 recruit formin-DAAM1 to A-P sites, where it interacts with PDZ-RhoGEF, activates RhoA, and increases myosin contractility, bending the neural plate and mediating directed intercalation of cells [103]. A comparable mechanism has been observed to propel the convergent extension movements of MSCs during the gastrulation process of Xenopus laevis. In Xenopus laevis gastrulation, Dsh and Fritz induce localization of septin towards the mediolateral vertices, where they restrict junctional shrinkage and cortical contractility of cortical actomyosin spatially to the margins of A-P cell ends [104,105]. Collectively, these investigations demonstrate how spatial cytoskeleton modification resulting from asymmetric PCP localization leads to collectively polarized cell behaviors.

- (ii)

- Positioning—Cilia and Centrosome: PCP controls the orientation of microtubule-based structures such as cilia and the mitotic spindle by regulating the positioning of the mitotic spindle along the plane of epithelial cells through interaction with the SOC (spindle orientation complex), followed by binding of microtubules astral to the cell periphery with the help of dynein complex [106]. To orient the spindle posteriorly, astral microtubules and the dynein complex are brought to the posterior cortex through the interaction of Dsh with Mud/NuMA, and Mud/NuMA is recruited by Pins/LGN on the anterior side, which causes the spindle to orient A-P. A non-dividing inner ear cell’s kinocilium is orientated by PCP in conjunction with its spindle orientation machinery [107,108]. The mPins/LGN and Gai localize in vestibular hair cells to the abneural periphery, which is located across from Vangl2; they are necessary for the positioning of kinocilia, followed by subsequent stereocilia bundle alignment [107]. Dynein and the plus ends of microtubules also exhibit an abneural bias, indicating that Gai-mPins/LGN pull on microtubules through a process akin to that because it is responsible for centrosome positioning during spindle orientation. According to one study, Vangl2 is needed for Gai-Pins/LGN-crescent to properly align between cells that coordinate the positioning and polarity of kinocilia and stereocilia, respectively, throughout the tissue [107]. Studies have observed that PCP is needed for asymmetric positioning of cilia in a wide range of cells [67,68,69,109]. Hence, PCP determines both the plane of cell division in dividing cells and specifies cilia positioning in non-dividing cells.

- (iii)

- Distal Positioning—Wing Hairs: Every Drosophila wing blade cell has a distal end with an actin-rich protrusion. The locations of wing hair and the Fz-Dsh-Fmi positions are closely correlated, which implies that core proteins may be responsible for localizing cytoskeletal regulators to certain areas of cells [110]. A group of proteins known as Fuzzy, Fritz, and Inturned is recruited by Vang to the proximal junction, which negatively regulates the formation of actin pre-hairs [103,104]. Actin polymerization is thought to be repressed by Fuzzy, Fritz, and Inturned proteins by regulating multiple wing hairs, a GBD/FH (GTP-binding/formin homology)-3 domain protein [110,111,112]. As a result, actin nucleation occurs at distant positions within the cell, and ectopic actin bundles grow over the apical surface in the absence of multiple wing hairs [113]. The pre-hair nucleation process precedes distal nucleation, and casein kinase 1g CK1/gilamesh is required for further vesicle trafficking coordination with Rab11 [114]. Rho and Drok (Rho–kinase complex) also play a role in wing-hair formation, but the precise role of Rho is tedious to explore because of its involvement in various functions in cells, including cell division and cell shape [115,116].

11. Cochlea

12. Skin

13. Other Signaling Pathways

- (i)

- Wnt Signaling: The Wnt protein activates the PCP signaling pathway through the activation of a transmembrane protein called Fz [9]. Data from multiple vertebrate investigations showed that Wnt11 and Wnt5a are involved in the induction of PCP [142,143,144,145]. Wing experiments on Drosophila reported that dWnt4 and Wg exhibit a crucial instructive role in positioning the PCP axis [146]. It has been demonstrated that Wnt5a interacts with complex receptors in PCP signaling that contain Ryk, Fz, Ror2, and Vangl2 [146,147,148]. In vertebrates, Wnt5a and Wnt11 also play an instructive role in activating PCP [147,149]. Studies on mutants (silberblick and pipetail) observed that mutations in Wnt11 and Wnt5a exhibit defective A-P axis (shortened and broadened) because of disrupted convergent extension movements, indicating that a Wnt signaling pathway is needed to control the convergent extension process via PCP [90,147]. Wnt signaling is not only involved in the regulation of PCP-mediated convergent extension processes but also mediates limb elongation by regulating PCP. Outcomes obtained from the Wnt5a mutant mice model showed that Wnt5a is implicated in the regulation of PCP-mediated limb elongation [150]. Genetic studies on the Wnt5a null mice models found that Wnt5a is very crucial for the establishment of PCP in the developing limb [151].

- (ii)

- Hippo Signaling: Hippo signaling is considered as a key regulator of organ size by regulating cell apoptosis and proliferation in mammals and flies [152]. Several lines of experimental evidence have reported the crosstalk between Hippo and PCP signaling pathways [152,153]. The relationship between Hippo and PCP signaling may be crucial for regulating the orientation of cell division during embryonic development, which is crucial for defining the form of tissues [154]. Ft, a proto-cadherin molecule of the Hippo signaling pathway, is needed for proper PCP in multiple developing tissues in Drosophila like fate choice positioning during the development of ommatidia, hair positioning in the abdomen and wings, and larval denticle orientation [30,48,155,156]. Through the regulation of Ft activity, patterned Ds serve as a cue for PCP orientation and the formation of imaginal discs in Drosophila [30,49,157,158]. While depletion of Fj and Ds causes partial changes in the growth of wings, PCP is engaged in the normal development of wings with uniform expression of Fj and Ds [50,51,153]. The study on the Ft mutant showed that the absence of the ECD (extracellular domain) greatly improved the PCP defects in the abdomen and wings of the ft mutant [157]. An in vivo study conducted on mammals observed that depletion of Fat4 is associated with PCP defects owing to loss of Ds1 [158,159,160]. It has been proposed that there is an overlap between PCP and Hippo functions since the Hippo pathway controls Fj expression [152]. Atrophine/Grunge (a transcriptional co-regulator) is also involved in the regulation of PCP by interacting with the ICD (intracellular domain) of Ft [52].

- (iii)

- Notch Signaling: Notch signaling is a highly conserved signaling cascade involved in the coordination of multiple developmental processes [161,162,163]. It has been demonstrated that Notch signaling is regulated by PCP, like in the development of Drosophila legs and eyes [163,164]. Studies observed the interplay of Notch signaling and PCP in ommatidial rotation in the eyes of insects [164,165,166]. One study on PCP mutant legs showed that ectopic Notch activity is associated with ectopic joints, indicating that PCP regulates Notch signaling [167]. In the Drosophila eye, PCP/Fz signaling determines the R3 fate from the precursor while inducing Notch-mediated signaling in adjacent cells to determine the R4 fate [164,165,166]. Genetic alterations in PCP result in random location of the ommatidial, R3/R4 specification, and related chirality [168].

- (iv)

- Sonic Hedgehog (Shh) signaling: The complex signal transduction mechanisms that control the finely tuned developmental processes of multicellular animals include the Sonic Hedgehog (Shh) signaling cascade. It also has a significant part in the processes of post-embryonic tissue regeneration and repair in addition to setting the patterns of cellular differentiation that control the creation of complex organs. The development of diverse neuronal populations in the central nervous system is specifically linked to Shh signaling [169]. The Shh signaling pathway involves a series of molecular events that occur when the Shh protein binds to its receptor, Patched (Ptch), relieving its inhibition on another receptor called Smoothened (Smo). This activation of Smo triggers a cascade of intracellular events, ultimately leading to the activation of transcription factors such as Gli proteins. These Gli proteins then regulate the expression of target genes involved in cell fate determination, proliferation, and differentiation. The Shh signaling pathway is essential for the development of various tissues and organs, including the central nervous system, limbs, and organs such as the lungs and gastrointestinal tract. Dysregulation of this pathway can lead to developmental defects and diseases, including various types of cancer. Therefore, understanding the mechanisms of Shh signaling holds great promise for both developmental biology and clinical applications.

14. Negative Regulation

15. Genetic Disorders

16. CRISPR/Cas9

17. Challenges in Planar Cell Polarity (PCP)

18. Conclusion and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ajduk, A.; Zernicka-Goetz, M. Polarity and cell division orientation in the cleavage embryo: From worm to human. MHR Basic Sci. Reprod. Med. 2016, 22, 691–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, R.S.; Roszko, I.; Solnica-Krezel, L. Planar cell polarity: Coordinating morphogenetic cell behaviors with embryonic polarity. Dev. Cell 2011, 21, 120–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, M.T.; Wallingford, J.B. Planar cell polarity in development and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 18, 375–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodrich, L.V.; Strutt, D. Principles of planar polarity in animal development. Development 2011, 138, 1877–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adler, P.N. The frizzled/stan pathway and planar cell polarity in the Drosophila wing. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 2012, 101, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Peng, Y.; Axelrod, J.D. Asymmetric protein localization in planar cell polarity: Mechanisms, puzzles, and challenges. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 2012, 101, 33–53. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lawrence, P.A.; Casal, J. The mechanisms of planar cell polarity, growth and the Hippo pathway: Some known unknowns. Dev. Biol. 2013, 377, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Mlodzik, M. Wnt-Frizzled/planar cell polarity signaling: Cellular orientation by facing the wind (Wnt). Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2015, 31, 623–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydeck, W.; Liu, A. PCP effector proteins inturned and fuzzy play nonredundant roles in the patterning but not convergent extension of mammalian neural tube. Dev. Dyn. 2011, 240, 1938–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, P.A.; Struhl, G.; Casal, J. Planar cell polarity: One or two pathways? Nat. Rev. Genet. 2007, 8, 555–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strutt, D. The planar polarity pathway. Curr. Biol. 2008, 18, R898–R902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vladar, E.K.; Antic, D.; Axelrod, J.D. Planar cell polarity signaling: The developing cell’s compass. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2009, 1, a002964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davey, C.F.; Moens, C.B. Planar cell polarity in moving cells: Think globally, act locally. Development 2017, 144, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfgang, W.J.; Fristrom, D.; Fristrom, J.W. The pupal cuticle of Drosophila: Differential ultrastructural immunolocalization of cuticle proteins. J. Cell Biol. 1986, 102, 306–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adler, P.N. Planar signaling and morphogenesis in Drosophila. Dev. Cell 2002, 2, 525–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, T.J.; Mlodzik, M. Planar cell polarization: An emerging model points in the right direction. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2005, 21, 155–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, P.A.; Casal, J.; Struhl, G. Cell interactions and planar polarity in the abdominal epidermis of Drosophila. Development 2004, 131, 4651–4664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mlodzik, M. Planar polarity in the Drosophila eye: A multifaceted view of signaling specificity and cross-talk. EMBO J. 1999, 18, 6873–6879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridges, C.B.; Brehme, K.S. The Mutants of Drosophila Melanogaster; Publication Carnegie Institution of Washington, D.C.: Washington, DC, USA, 1944. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, N.A.; Tolwinski, N.S. Spatially defined Dsh–Lgl interaction contributes to directional tissue morphogenesis. J. Cell Sci. 2010, 123, 3157–3165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilder, D.; Perrimon, N. Localization of apical epithelial determinants by the basolateral PDZ protein Scribble. Nature 2000, 403, 676–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilder, D. Epithelial polarity and proliferation control: Links from the Drosophila neoplastic tumor suppressors. Genes Dev. 2004, 18, 1909–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawrence, P.A.; Shelton, P.M. The determination of polarity in the developing insect retina. Development 1975, 33, 471–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regolini, M.F. Centrosome: Is it a geometric, noise resistant, 3D interface that translates morphogenetic signals into precise locations in the cell? Ital. J. Anat. Embryol. 2013, 118, 19–66. [Google Scholar]

- Wansleeben, C.; Meijlink, F. The planar cell polarity pathway in vertebrate development. Dev. Dyn. 2011, 240, 616–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, C.; Shao, H.; Strutt, H.; Strutt, D. Molecular mechanisms mediating asymmetric subcellular localisation of the core planar polarity pathway proteins. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2020, 48, 1297–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deans, M.R. Conserved and divergent principles of planar polarity revealed by hair cell development and function. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 742391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zallen, J.A. Planar polarity and tissue morphogenesis. Cell 2007, 129, 1051–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yen, H.J.; Tayeh, M.K.; Mullins, R.F.; Stone, E.M.; Sheffield, V.C.; Slusarski, D.C. Bardet–Biedl syndrome genes are important in retrograde intracellular trafficking and Kupffer’s vesicle cilia function. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2006, 15, 667–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Yang, C.H.; McNeill, H.; Simon, M.A.; Axelrod, J.D. Fidelity in planar cell polarity signaling. Nature 2003, 421, 543–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, M.; Mlodzik, M. Planar cell polarity signaling: From fly development to human disease. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2008, 42, 517–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelrod, J.D. Unipolar membrane association of Dishevelled mediates Frizzled planar cell polarity signaling. Genes Dev. 2001, 15, 1182–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strutt, D.I. Asymmetric localization of frizzled and the establishment of cell polarity in the Drosophila wing. Mol. Cell 2001, 7, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usui, T.; Shima, Y.; Shimada, Y.; Hirano, S.; Burgess, R.W.; Schwarz, T.L.; Takeichi, M.; Uemura, T. Flamingo, a seven-pass transmembrane cadherin, regulates planar cell polarity under the control of Frizzled. Cell 1999, 98, 585–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.S.; Antic, D.; Matis, M.; Logan, C.Y.; Povelones, M.; Anderson, G.A.; Nusse, R.; Axelrod, J.D. Asymmetric homotypic interactions of the atypical cadherin flamingo mediate intercellular polarity signaling. Cell 2008, 133, 1093–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimada, Y.; Yonemura, S.; Ohkura, H.; Strutt, D.; Uemura, T. Polarized transport of Frizzled along the planar microtubule arrays in Drosophila wing epithelium. Dev. Cell 2006, 10, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strutt, H.; Strutt, D. Differential stability of flamingo protein complexes underlies the establishment of planar polarity. Curr. Biol. 2008, 18, 1555–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinson, C.R.; Adler, P.N. Directional non-cell autonomy and the transmission of polarity information by the frizzled gene of Drosophila. Nature 1987, 329, 549–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amonlirdviman, K.; Khare, N.A.; Tree, D.R.; Chen, W.S.; Axelrod, J.D.; Tomlin, C.J. Mathematical modeling of planar cell polarity to understand domineering nonautonomy. Science 2005, 307, 423–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djiane, A.; Yogev, S.; Mlodzik, M. The apical determinants aPKC and dPatj regulate Frizzled-dependent planar cell polarity in the Drosophila eye. Cell 2005, 121, 621–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessen, J.R.; Topczewski, J.; Bingham, S.; Sepich, D.S.; Marlow, F.; Chandrasekhar, A.; Solnica-Krezel, L. Zebrafish trilobite identifies new roles for Strabismus in gastrulation and neuronal movements. Nat. Cell Biol. 2002, 4, 610–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, M.L.; Mlodzik, M. Drosophila Furrowed/Selectin is a homophilic cell adhesion molecule stabilizing Frizzled and intercellular interactions during PCP establishment. Dev. Cell 2013, 26, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenny, A.; Darken, R.S.; Wilson, P.A.; Mlodzik, M. Prickle and Strabismus form a functional complex to generate a correct axis during planar cell polarity signaling. EMBO J. 2003, 22, 4409–4420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tree, D.R.; Shulman, J.M.; Rousset, R.; Scott, M.P.; Gubb, D.; Axelrod, J.D. Prickle mediates feedback amplification to generate asymmetric planar cell polarity signaling. Cell 2002, 109, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, G.; Jenny, A.; Klein, T.J.; Eaton, S.; Mlodzik, M. Diego interacts with Prickle and Strabismus/Van Gogh to localize planar cell polarity complexes. Development 2004, 131, 4467–4476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feiguin, F.; Hannus, M.; Mlodzik, M.; Eaton, S. The ankyrin repeat protein Diego mediates Frizzled-dependent planar polarization. Dev. Cell 2001, 1, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenny, A.; Reynolds-Kenneally, J.; Das, G.; Burnett, M.; Mlodzik, M. Diego and Prickle regulate Frizzled planar cell polarity signaling by competing for Dishevelled binding. Nat. Cell Biol. 2005, 7, 691–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebnet, K.; Kummer, D.; Steinbacher, T.; Singh, A.; Nakayama, M.; Matis, M. Regulation of cell polarity by cell adhesion receptors. In Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; Volume 81, pp. 2–12. [Google Scholar]

- Casal, J.; Struhl, G.; Lawrence, P.A. Developmental compartments and planar polarity in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 2002, 12, 1189–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.H.; Axelrod, J.D.; Simon, M.A. Regulation of Frizzled by fat-like cadherins during planar polarity signaling in the Drosophila compound eye. Cell 2002, 108, 675–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawls, A.S.; Guinto, J.B.; Wolff, T. The cadherins fat and dachsous regulate dorsal/ventral signaling in the Drosophila eye. Curr. Biol. 2002, 12, 1021–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matakatsu, H.; Blair, S.S. Interactions between Fat and Dachsous and the regulation of planar cell polarity in the Drosophila wing. Development 2004, 131, 3785–3794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, M.A. Planar cell polarity in the Drosophila eye is directed by graded Four-jointed and Dachsous expression. Development 2004, 131, 6175–6184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fanto, M.; Clayton, L.; Meredith, J.; Hardiman, K.; Charroux, B.; Kerridge, S.; McNeill, H. The tumor-suppressor and cell adhesion molecule Fat controls planar polarity via physical interactions with Atrophin, a transcriptional co-repressor. Development 2003, 130, 763–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heisenberg, C.P.; Tada, M.; Rauch, G.J.; Saúde, L.; Concha, M.L.; Geisler, R.; Stemple, D.L.; Smith, J.C.; Wilson, S.W. Silberblick/Wnt11 mediates convergent extension movements during zebrafish gastrulation. Nature 2000, 405, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tada, M.; Smith, J.C. Xwnt11 is a target of Xenopus Brachyury: Regulation of gastrulation movements via Dishevelled, but not through the canonical Wnt pathway. Development 2000, 127, 2227–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topczewski, J.; Sepich, D.S.; Myers, D.C.; Walker, C.; Amores, A.; Lele, Z.; Hammerschmidt, M.; Postlethwait, J.; Solnica-Krezel, L. The zebrafish glypican knypek controls cell polarity during gastrulation movements of convergent extension. Dev. Cell 2001, 1, 251–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallingford, J.B.; Rowning, B.A.; Vogeli, K.M.; Rothbächer, U.; Fraser, S.E.; Harland, R.M. Dishevelled controls cell polarity during Xenopus gastrulation. Nature 2000, 405, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shindo, A.; Inoue, Y.; Kinoshita, M.; Wallingford, J.B. PCP-dependent transcellular regulation of actomyosin oscillation facilitates convergent extension of vertebrate tissue. Dev. Biol. 2019, 446, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, R.; Davidson, L.; Edlund, A.; Elul, T.; Ezin, M.; Shook, D.; Skoglund, P. Mechanisms of convergence and extension by cell intercalation. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 2000, 355, 897–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, C.; Kiskowski, M.; Pouille, P.A.; Farge, E.; Solnica-Krezel, L. Cooperation of polarized cell intercalations drives convergence and extension of presomitic mesoderm during zebrafish gastrulation. J. Cell Biol. 2008, 180, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallingford, J.B.; Harland, R.M. Neural tube closure requires Dishevelled-dependent convergent extension of the midline. Development 2002, 129, 5815–5825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawk, M.; Araya, C.; Lyons, D.A.; Reugels, A.M.; Girdler, G.C.; Bayley, P.R.; Hyde, D.R.; Tada, M.; Clarke, J.D. A mirror-symmetric cell division that orchestrates neuroepithelial morphogenesis. Nature 2007, 446, 797–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciruna, B.; Jenny, A.; Lee, D.; Mlodzik, M.; Schier, A.F. Planar cell polarity signaling couples cell division and morphogenesis during neurulation. Nature 2006, 439, 220–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kibar, Z.; Torban, E.; McDearmid, J.R.; Reynolds, A.; Berghout, J.; Mathieu, M.; Kirillova, I.; De Marco, P.; Merello, E.; Hayes, J.M.; et al. Mutations in VANGL1 associated with neural-tube defects. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 356, 1432–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, Y.P.; Zhang, T.; Li, H.; Wu, B.L.; Jin, L.; Wang, H.Y. VANGL2 mutations in human cranial neural-tube defects. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 2232–2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devenport, D.; Fuchs, E. Planar polarization in embryonic epidermis orchestrates global asymmetric morphogenesis of hair follicles. Nat. Cell Biol. 2008, 10, 1257–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, N.; Hawkins, C.; Nathans, J. Frizzled6 controls hair patterning in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 9277–9281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antic, D.; Stubbs, J.L.; Suyama, K.; Kintner, C.; Scott, M.P.; Axelrod, J.D. Planar cell polarity enables posterior localization of nodal cilia and left-right axis determination during mouse and Xenopus embryogenesis. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e8999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borovina, A.; Superina, S.; Voskas, D.; Ciruna, B. Vangl2 directs the posterior tilting and asymmetric localization of motile primary cilia. Nat. Cell Biol. 2010, 12, 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashimoto, M.; Shinohara, K.; Wang, J.; Ikeuchi, S.; Yoshiba, S.; Meno, C.; Nonaka, S.; Takada, S.; Hatta, K.; Wynshaw-Boris, A.; et al. Planar polarization of node cells determines the rotational axis of node cilia. Nat. Cell Biol. 2010, 12, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quesada-Hernández, E.; Caneparo, L.; Schneider, S.; Winkler, S.; Liebling, M.; Fraser, S.E.; Heisenberg, C.P. Stereotypical cell division orientation controls neural rod midline formation in zebrafish. Curr. Biol. 2010, 20, 1966–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenstermaker, A.G.; Prasad, A.A.; Bechara, A.; Adolfs, Y.; Tissir, F.; Goffinet, A.; Zou, Y.; Pasterkamp, R.J. Wnt/planar cell polarity signaling controls the anterior–posterior organization of monoaminergic axons in the brainstem. J. Neurosci. 2010, 30, 16053–16064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodrich, L.V. The plane facts of PCP in the CNS. Neuron 2008, 60, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikolopoulou, E.; Galea, G.L.; Rolo, A.; Greene, N.D.; Copp, A.J. Neural tube closure: Cellular, molecular and biomechanical mechanisms. Development 2017, 144, 552–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kancherla, V. Neural tube defects: A review of global prevalence, causes, and primary prevention. Child’s Nerv. Syst. 2023, 39, 1703–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrman, R.E.; Vaughan, V.C., III. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics, 12th ed.; WB Saunders company: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- McComb, J.G. A practical clinical classification of spinal neural tube defects. Child’s Nerv. Syst. 2015, 31, 1641–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detrait, E.R.; George, T.M.; Etchevers, H.C.; Gilbert, J.R.; Vekemans, M.; Speer, M.C. Human neural tube defects: Developmental biology, epidemiology, and genetics. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 2005, 27, 515–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ybot-Gonzalez, P.; Savery, D.; Gerrelli, D.; Signore, M.; Mitchell, C.E.; Faux, C.H.; Greene, N.D.; Copp, A.J. Convergent extension, planar-cell-polarity signaling and initiation of mouse neural tube closure. Development 2007, 134, 789–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallingford, J.B. Planar cell polarity, ciliogenesis and neural tube defects. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2006, 15 (Suppl. S2), R227–R234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rai, S.; Leydier, L.; Sharma, S.; Katwala, J.; Sahu, A. A quest for genetic causes underlying signaling pathways associated with neural tube defects. Front. Pediatr. 2023, 11, 1126209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copp, A.J.; Greene, N.D. Genetics and development of neural tube defects. J. Pathol. A J. Pathol. Soc. Great Br. Irel. 2010, 220, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marlow, F.; Zwartkruis, F.; Malicki, J.; Neuhauss, S.C.; Abbas, L.; Weaver, M.; Driever, W.; Solnica-Krezel, L. Functional Interactions of Genes Mediating Convergent Extension, knypekandtrilobite, during the Partitioning of the Eye Primordium in Zebrafish. Dev. Biol. 1998, 203, 382–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kibar, Z.; Vogan, K.J.; Groulx, N.; Justice, M.J.; Underhill, D.A.; Gros, P. Ltap, a mammalian homolog of Drosophila Strabismus/Van Gogh, is altered in the mouse neural tube mutant Loop-tail. Nat. Genet. 2001, 28, 251–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Guo, N.; Nathans, J. The role of Frizzled3 and Frizzled6 in neural tube closure and in the planar polarity of inner-ear sensory hair cells. J. Neurosci. 2006, 26, 2147–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.; Smallwood, P.M.; Wang, Y.; Vidaltamayo, R.; Reed, R.; Nathans, J. Frizzled 1 and frizzled 2 genes function in palate, ventricular septum and neural tube closure: General implications for tissue fusion processes. Development 2010, 137, 3707–3717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinoshita, N.; Sasai, N.; Misaki, K.; Yonemura, S. Apical accumulation of Rho in the neural plate is important for neural plate cell shape change and neural tube formation. Mol. Biol. Cell 2008, 19, 2289–2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curtin, J.A.; Quint, E.; Tsipouri, V.; Arkell, R.M.; Cattanach, B.; Copp, A.J.; Henderson, D.J.; Spurr, N.; Stanier, P.; Fisher, E.M.; et al. Mutation of Celsr1 disrupts planar polarity of inner ear hair cells and causes severe neural tube defects in the mouse. Curr. Biol. 2003, 13, 1129–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koca, Y.; Collu, G.M.; Mlodzik, M. Wnt-frizzled planar cell polarity signaling in the regulation of cell motility. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 2022, 150, 255–297. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Murdoch, J.N.; Doudney, K.; Paternotte, C.; Copp, A.J.; Stanier, P. Severe neural tube defects in the loop-tail mouse result from mutation of Lpp1, a novel gene involved in floor plate specification. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001, 10, 2593–2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, D.; Jones, C.; Rzadzinska, A.; Mark, S.; Zhang, X.; Steel, K.P.; Dai, X.; Chen, P. Wnt5a functions in planar cell polarity regulation in mice. Dev. Biol. 2007, 306, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, T.; Raya, Á.; Kawakami, Y.; Callol-Massot, C.; Capdevila, J.; Rodríguez-Esteban, C.; Belmonte, J.C. Noncanonical Wnt signaling regulates midline convergence of organ primordia during zebrafish development. Genes Dev. 2005, 19, 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veeman, M.T.; Slusarski, D.C.; Kaykas, A.; Louie, S.H.; Moon, R.T. Zebrafish prickle, a modulator of noncanonical Wnt/Fz signaling, regulates gastrulation movements. Curr. Biol. 2003, 13, 680–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, M.; Nakabayashi, J.; Sakaguchi, T.; Yamamoto, T.S.; Takahashi, H.; Takeda, H.; Ueno, N. The prickle-related gene in vertebrates is essential for gastrulation cell movements. Curr. Biol. 2003, 13, 674–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, G.; Huang, X.; Hua, Y.; Mu, D. Roles of planar cell polarity pathways in the development of neutral tube defects. J. Biomed. Sci. 2011, 18, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigo Albors, A.; Tazaki, A.; Rost, F.; Nowoshilow, S.; Chara, O.; Tanaka, E.M. Planar cell polarity-mediated induction of neural stem cell expansion during axolotl spinal cord regeneration. Elife 2015, 4, e10230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viktorinová, I.; Pismen, L.M.; Aigouy, B.; Dahmann, C. Modelling planar polarity of epithelia: The role of signal relay in collective cell polarization. J. R. Soc. Interface 2011, 8, 1059–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roignot, J.; Peng, X.; Mostov, K. Polarity in mammalian epithelial morphogenesis. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2013, 5, a013789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beane, W.S.; Tseng, A.S.; Morokuma, J.; Lemire, J.M.; Levin, M. Inhibition of planar cell polarity extends neural growth during regeneration, homeostasis, and development. Stem Cells Dev. 2012, 21, 2085–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warchol, M.E.; Montcouquiol, M. Maintained expression of the planar cell polarity molecule Vangl2 and reformation of hair cell orientation in the regenerating inner ear. J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 2010, 11, 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salbreux, G.; Barthel, L.K.; Raymond, P.A.; Lubensky, D.K. Coupling mechanical deformations and planar cell polarity to create regular patterns in the zebrafish retina. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2012, 8, e1002618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, R. Shaping the vertebrate body plan by polarized embryonic cell movements. Science 2002, 298, 1950–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goto, T.; Keller, R. The planar cell polarity gene strabismus regulates convergence and extension and neural fold closure in Xenopus. Dev. Biol. 2002, 247, 165–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishimura, T.; Honda, H.; Takeichi, M. Planar cell polarity links axes of spatial dynamics in neural-tube closure. Cell 2012, 149, 1084–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.K.; Shindo, A.; Park, T.J.; Oh, E.C.; Ghosh, S.; Gray, R.S.; Lewis, R.A.; Johnson, C.A.; Attie-Bittach, T.; Katsanis, N.; et al. Planar cell polarity acts through septins to control collective cell movement and ciliogenesis. Science 2010, 329, 1337–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shindo, A.; Wallingford, J.B. PCP and septins compartmentalize cortical actomyosin to direct collective cell movement. Science 2014, 343, 649–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ségalen, M.; Johnston, C.A.; Martin, C.A.; Dumortier, J.G.; Prehoda, K.E.; David, N.B.; Doe, C.Q.; Bellaïche, Y. The Fz-Dsh planar cell polarity pathway induces oriented cell division via Mud/NuMA in Drosophila and zebrafish. Dev. Cell 2010, 19, 740–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ezan, J.; Lasvaux, L.; Gezer, A.; Novakovic, A.; May-Simera, H.; Belotti, E.; Lhoumeau, A.C.; Birnbaumer, L.; Beer-Hammer, S.; Borg, J.P.; et al. Primary cilium migration depends on G-protein signaling control of subapical cytoskeleton. Nat. Cell Biol. 2013, 15, 1107–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarchini, B.; Jolicoeur, C.; Cayouette, M. A molecular blueprint at the apical surface establishes planar asymmetry in cochlear hair cells. Dev. Cell 2013, 27, 88–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, H.; Hu, J.; Chen, W.; Elliott, G.; Andre, P.; Gao, B.; Yang, Y. Planar cell polarity breaks bilateral symmetry by controlling ciliary positioning. Nature 2010, 466, 378–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strutt, D.; Warrington, S.J. Planar polarity genes in the Drosophila wing regulate the localisation of the FH3-domain protein Multiple Wing Hairs to control the site of hair production. Development 2008, 135, 3103–3111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, P.N.; Zhu, C.; Stone, D. Inturned localizes to the proximal side of wing cells under the instruction of upstream planar polarity proteins. Curr. Biol. 2004, 14, 2046–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Huen, D.; Morely, T.; Johnson, G.; Gubb, D.; Roote, J.; Adler, P.N. The multiple-wing-hairs gene encodes a novel GBD–FH3 domain-containing protein that functions both prior to and after wing hair initiation. Genetics 2008, 180, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, L.L.; Adler, P.N. Tissue polarity genes of Drosophila regulate the subcellular location for prehair initiation in pupal wing cells. J. Cell Biol. 1993, 123, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gault, W.J.; Olguin, P.; Weber, U.; Mlodzik, M. Drosophila CK1-γ, gilgamesh, controls PCP-mediated morphogenesis through regulation of vesicle trafficking. J. Cell Biol. 2012, 196, 605–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winter, C.G.; Wang, B.; Ballew, A.; Royou, A.; Karess, R.; Axelrod, J.D.; Luo, L. Drosophila Rho-associated kinase (Drok) links Frizzled-mediated planar cell polarity signaling to the actin cytoskeleton. Cell 2001, 105, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, J.; Lu, Q.; Fang, X.; Adler, P.N. Rho1 has multiple functions in Drosophila wing planar polarity. Dev. Biol. 2009, 333, 186–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, T.J.; Haigo, S.L.; Wallingford, J.B. Ciliogenesis defects in embryos lacking inturned or fuzzy function are associated with failure of planar cell polarity and Hedgehog signaling. Nat. Genet. 2006, 38, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montcouquiol, M.; Crenshaw, I.I.I.E.B.; Kelley, M.W. Noncanonical Wnt signaling and neural polarity. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2006, 29, 363–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montcouquiol, M.; Rachel, R.A.; Lanford, P.J.; Copeland, N.G.; Jenkins, N.A.; Kelley, M.W. Identification of Vangl2 and Scrb1 as planar polarity genes in mammals. Nature 2003, 423, 173–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, X.; Borchers, A.G.; Jolicoeur, C.; Rayburn, H.; Baker, J.C.; Tessier-Lavigne, M. PTK7/CCK-4 is a novel regulator of planar cell polarity in vertebrates. Nature 2004, 430, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Hamblet, N.S.; Mark, S.; Dickinson, M.E.; Brinkman, B.C.; Segil, N.; Fraser, S.E.; Chen, P.; Wallingford, J.B.; Wynshaw-Boris, A. Dishevelled genes mediate a conserved mammalian PCP pathway to regulate convergent extension during neurulation. Development 2006, 133, 1767–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabdoub, A.; Donohue, M.J.; Brennan, A.; Wolf, V.; Montcouquiol, M.; Sassoon, D.A.; Hseih, J.C.; Rubin, J.S.; Salinas, P.C.; Kelley, M.W. Wnt signaling mediates reorientation of outer hair cell stereociliary bundles in the mammalian cochlea. Development 2003, 130, 2375–2384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.; Roper, V.C.; Foucher, I.; Qian, D.; Banizs, B.; Petit, C.; Yoder, B.K.; Chen, P. Ciliary proteins link basal body polarization to planar cell polarity regulation. Nat. Genet. 2008, 40, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelrod, J.D. Basal bodies, kinocilia and planar cell polarity. Nat. Genet. 2008, 40, 10–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkins, R.D.; Lovett, M. The developmental genetics of auditory hair cells. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2004, 13, R289–R296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooker, R.; Hozumi, K.; Lewis, J. Notch ligands with contrasting functions: Jagged1 and Delta1 in the mouse inner ear. Development 2006, 133, 1277–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Mark, S.; Zhang, X.; Qian, D.; Yoo, S.J.; Radde-Gallwitz, K.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, X.; Collazo, A.; Wynshaw-Boris, A.; et al. Regulation of polarized extension and planar cell polarity in the cochlea by the vertebrate PCP pathway. Nat. Genet. 2005, 37, 980–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montcouquiol, M.; Sans, N.; Huss, D.; Kach, J.; Dickman, J.D.; Forge, A.; Rachel, R.A.; Copeland, N.G.; Jenkins, N.A.; Bogani, D.; et al. Asymmetric localization of Vangl2 and Fz3 indicate novel mechanisms for planar cell polarity in mammals. J. Neurosci. 2006, 26, 5265–5275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dworkin, S.; Jane, S.M.; Darido, C. The planar cell polarity pathway in vertebrate epidermal development, homeostasis and repair. Organogenesis 2011, 7, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Nathans, J. Tissue/planar cell polarity in vertebrates: New insights and new questions. Development 2007, 134, 647–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murayama, K.; Kimura, T.; Tarutani, M.; Tomooka, M.; Hayashi, R.; Okabe, M.; Nishida, K.; Itami, S.; Katayama, I.; Nakano, T. Akt activation induces epidermal hyperplasia and proliferation of epidermal progenitors. Oncogene 2007, 26, 4882–4888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morel, V.; Arias, A.M. Armadillo/β-catenin-dependent Wnt signaling is required for the polarisation of epidermal cells during dorsal closure in Drosophila. Development 2004, 131, 3273–3283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravni, A.; Qu, Y.; Goffinet, A.M.; Tissir, F. Planar cell polarity cadherin Celsr1 regulates skin hair patterning in the mouse. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2009, 129, 2507–2509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, B.; Fischer, J.A. Ral GTPase promotes asymmetric Notch activation in the Drosophila eye in response to Frizzled/PCP signaling by repressing ligand-independent receptor activation. Development 2011, 138, 1349–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, S.E.; Beronja, S.; Pasolli, H.A.; Fuchs, E. Asymmetric cell divisions promote Notch-dependent epidermal differentiation. Nature 2011, 470, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ting, S.B.; Caddy, J.; Wilanowski, T.; Auden, A.; Cunningham, J.M.; Elias, P.M.; Holleran, W.M.; Jane, S.M. The epidermis of grhl3-null mice displays altered lipid processing and cellular hyperproliferation. Organogenesis 2005, 2, 33–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caddy, J.; Wilanowski, T.; Darido, C.; Dworkin, S.; Ting, S.B.; Zhao, Q.; Rank, G.; Auden, A.; Srivastava, S.; Papenfuss, T.A.; et al. Epidermal wound repair is regulated by the planar cell polarity signaling pathway. Dev. Cell 2010, 19, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Lin, K.K.; Bhandari, A.; Spencer, J.A.; Xu, X.; Wang, N.; Lu, Z.; Gill, G.N.; Roop, D.R.; Wertz, P.; et al. The Grainyhead-like epithelial transactivator Get-1/Grhl3 regulates epidermal terminal differentiation and interacts functionally with LMO4. Dev. Biol. 2006, 299, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mace, K.A.; Pearson, J.C.; McGinnis, W. An epidermal barrier wound repair pathway in Drosophila is mediated by grainy head. Science 2005, 308, 381–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dynlacht, B.D.; Hoey, T.; Tjian, R. Isolation of coactivators associated with the TATA-binding protein that mediate transcriptional activation. Cell 1991, 66, 563–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Axelrod, J.D. Studies of epithelial PCP. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2009, 20, 956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhanot, P.; Brink, M.; Samos, C.H.; Hsieh, J.C.; Wang, Y.; Macke, J.P.; Andrew, D.; Nathans, J.; Nusse, R. A new member of the frizzled family from Drosophila functions as a Wingless receptor. Nature 1996, 382, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aigouy, B.; Farhadifar, R.; Staple, D.B.; Sagner, A.; Röper, J.C.; Jülicher, F.; Eaton, S. Cell flow reorients the axis of planar polarity in the wing epithelium of Drosophila. Cell 2010, 142, 773–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagner, A.; Merkel, M.; Aigouy, B.; Gaebel, J.; Brankatschk, M.; Jülicher, F.; Eaton, S. Establishment of global patterns of planar polarity during growth of the Drosophila wing epithelium. Curr. Biol. 2012, 22, 1296–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Roman, A.C.; Carvajal-Gonzalez, J.M.; Mlodzik, M. Wg and Wnt4 provide long-range directional input to planar cell polarity orientation in Drosophila. Nat. Cell Biol. 2013, 15, 1045–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grumolato, L.; Liu, G.; Mong, P.; Mudbhary, R.; Biswas, R.; Arroyave, R.; Vijayakumar, S.; Economides, A.N.; Aaronson, S.A. Canonical and noncanonical Wnts use a common mechanism to activate completely unrelated coreceptors. Genes Dev. 2010, 24, 2517–2530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, B.; Song, H.; Bishop, K.; Elliot, G.; Garrett, L.; English, M.A.; Andre, P.; Robinson, J.; Sood, R.; Minami, Y.; et al. Wnt signaling gradients establish planar cell polarity by inducing Vangl2 phosphorylation through Ror2. Dev. Cell 2011, 20, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andre, P.; Wang, Q.; Wang, N.; Gao, B.; Schilit, A.; Halford, M.M.; Stacker, S.A.; Zhang, X.; Yang, Y. The Wnt coreceptor Ryk regulates Wnt/planar cell polarity by modulating the degradation of the core planar cell polarity component Vangl2. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 44518–44525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gros, J.; Serralbo, O.; Marcelle, C. WNT11 acts as a directional cue to organize the elongation of early muscle fibres. Nature 2009, 457, 589–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamaguchi, T.P.; Bradley, A.; McMahon, A.P.; Jones, S. A Wnt5a pathway underlies outgrowth of multiple structures in the vertebrate embryo. Development 1999, 126, 1211–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grusche, F.A.; Richardson, H.E.; Harvey, K.F. Upstream regulation of the hippo size control pathway. Curr. Biol. 2010, 20, R574–R582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Irvine, K.D. Fat and expanded act in parallel to regulate growth through warts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 20362–20367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brittle, A.L.; Repiso, A.; Casal, J.; Lawrence, P.A.; Strutt, D. Four-jointed modulates growth and planar polarity by reducing the affinity of dachsous for fat. Curr. Biol. 2010, 20, 803–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Tournier, A.L.; Bates, P.A.; Gale, J.E.; Tapon, N.; Thompson, B.J. Planar polarization of the atypical myosin Dachs orients cell divisions in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 2011, 25, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hogan, J.; Valentine, M.; Cox, C.; Doyle, K.; Collier, S. Two frizzled planar cell polarity signals in the Drosophila wing are differentially organized by the Fat/Dachsous pathway. PLoS Genet. 2011, 7, e1001305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donoughe, S.; DiNardo, S. dachsous and frizzled contribute separately to planar polarity in the Drosophila ventral epidermis. Development 2011, 138, 2751–2759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matakatsu, H.; Blair, S.S. Separating the adhesive and signaling functions of the Fat and Dachsous protocadherins. Development 2006, 133, 2315–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, Y.; Mulvaney, J.; Zakaria, S.; Yu, T.; Morgan, K.M.; Allen, S.; Basson, M.A.; Francis-West, P.; Irvine, K.D. Characterization of a Dchs1 mutant mouse reveals requirements for Dchs1-Fat4 signaling during mammalian development. Development 2011, 138, 947–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saburi, S.; Hester, I.; Fischer, E.; Pontoglio, M.; Eremina, V.; Gessler, M.; Quaggin, S.E.; Harrison, R.; Mount, R.; McNeill, H. Loss of Fat4 disrupts PCP signaling and oriented cell division and leads to cystic kidney disease. Nat. Genet. 2008, 40, 1010–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Höng, J.C.; Ivanov, N.V.; Hodor, P.; Xia, M.; Wei, N.; Blevins, R.; Gerhold, D.; Borodovsky, M.; Liu, Y. Identification of new human cadherin genes using a combination of protein motif search and gene finding methods. J. Mol. Biol. 2004, 337, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiúza, U.M.; Arias, A.M. Cell and molecular biology of Notch. J. Endocrinol. 2007, 194, 459–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortini, M.E. Notch signaling: The core pathway and its posttranslational regulation. Dev. Cell 2009, 16, 633–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capilla, A.; Johnson, R.; Daniels, M.; Benavente, M.; Bray, S.J.; Galindo, M.I. Planar cell polarity controls directional Notch signaling in the Drosophila leg. Development 2012, 139, 2584–2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, M.T.; Bray, S.J. Frizzled regulation of Notch signaling polarizes cell fate in the Drosophila eye. Nature 1999, 397, 526–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fanto, M.; Mlodzik, M. Asymmetric Notch activation specifies photoreceptors R3 and R4 and planar polarity in the Drosophila eye. Nature 1999, 397, 523–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudhry, Z.; Rikani, A.A.; Choudhry, A.M.; Tariq, S.; Zakaria, F.; Asghar, M.W.; Sarfraz, M.K.; Haider, K.; Shafiq, A.A.; Mobassarah, N.J. Sonic hedgehog signalling pathway: A complex network. Ann. Neurosci. 2014, 21, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomlinson, A.; Struhl, G. Decoding vectorial information from a gradient: Sequential roles of the receptors Frizzled and Notch in establishing planar polarity in the Drosophila eye. Development 1999, 126, 5725–5738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bishop, S.A.; Klein, T.; Arias, A.M.; Couso, J.P. Composite signaling from Serrate and Delta establishes leg segments in Drosophila through Notch. Development 1999, 126, 2993–3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, J.; Mlodzik, M. Planar cell polarity signaling: Coordination of cellular orientation across tissues. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Dev. Biol. 2012, 1, 479–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carreira-Barbosa, F.; Concha, M.L.; Takeuchi, M.; Ueno, N.; Wilson, S.W.; Tada, M. Prickle 1 regulates cell movements during gastrulation and neuronal migration in zebrafish. Development 2003, 130, 4037–4046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaoka, T.; Furuse, M.; Ohtsuka, T.; Tsuchida, K.; Kishi, M. Vangl2 interaction plays a role in the proteasomal degradation of Prickle2. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 2912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strutt, H.; Searle, E.; Thomas-MacArthur, V.; Brookfield, R.; Strutt, D. A Cul-3-BTB ubiquitylation pathway regulates junctional levels and asymmetry of core planar polarity proteins. Development 2013, 140, 1693–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strutt, H.; Thomas-MacArthur, V.; Strutt, D. Strabismus promotes recruitment and degradation of farnesylated prickle in Drosophila melanogaster planar polarity specification. PLoS Genet. 2013, 9, e1003654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narimatsu, M.; Bose, R.; Pye, M.; Zhang, L.; Miller, B.; Ching, P.; Sakuma, R.; Luga, V.; Roncari, L.; Attisano, L.; et al. Regulation of planar cell polarity by Smurf ubiquitin ligases. Cell 2009, 137, 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luyten, A.; Su, X.; Gondela, S.; Chen, Y.; Rompani, S.; Takakura, A.; Zhou, J. Aberrant regulation of planar cell polarity in polycystic kidney disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. JASN 2010, 21, 1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juriloff, D.M.; Harris, M.J. A consideration of the evidence that genetic defects in planar cell polarity contribute to the etiology of human neural tube defects. Birth Defects Res. Part A Clin. Mol. Teratol. 2012, 94, 824–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sans, N.; Ezan, J.; Moreau, M.M.; Montcouquiol, M. Planar cell polarity gene mutations in autism spectrum disorder, intellectual disabilities, and related deletion/duplication syndromes. In Neuronal and Synaptic Dysfunction in Autism Spectrum Disorder and Intellectual Disability; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016; pp. 189–219. [Google Scholar]

- Hamblet, N.S.; Lijam, N.; Ruiz-Lozano, P.; Wang, J.; Yang, Y.; Luo, Z.; Mei, L.; Chien, K.R.; Sussman, D.J.; Wynshaw-Boris, A. Dishevelled 2 is essential for cardiac outflow tract development, somite segmentation and neural tube closure. Development 2002, 129, 5827–5838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezaei, M.; Cao, J.; Friedrich, K.; Kemper, B.; Brendel, O.; Grosser, M.; Adrian, M.; Baretton, G.; Breier, G.; Schnittler, H.J. The expression of VE-cadherin in breast cancer cells modulates cell dynamics as a function of tumor differentiation and promotes tumor–endothelial cell interactions. Histochem. Cell Biol. 2018, 149, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humphries, A.C.; Mlodzik, M. From instruction to output: Wnt/PCP signaling in development and cancer. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2018, 51, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Neogi, A.; Mani, A. The role of Wnt signaling in development of coronary artery disease and its risk factors. Open Biol. 2020, 10, 200128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Liu, A.; Wu, G.; Ding, H.F.; Huang, S.; Nahman, S.; Dong, Z. The CPLANE protein Intu protects kidneys from ischemia-reperfusion injury by targeting STAT1 for degradation. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, M.M.; Abu-Asab, M.S. Loss of endothelial planar cell polarity and cellular clearance mechanisms in age-related macular degeneration. Ultrastruct. Pathol. 2017, 41, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, H.M.; Rhee, H.J.; Murdoch, J.N.; Hildreth, V.; Peat, J.D.; Anderson, R.H.; Copp, A.J.; Chaudhry, B.; Henderson, D.J. Disruption of planar cell polarity signaling results in congenital heart defects and cardiomyopathy attributable to early cardiomyocyte disorganization. Circ. Res. 2007, 101, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, H.M.; Hildreth, V.; Peat, J.D.; Murdoch, J.N.; Kobayashi, K.; Chaudhry, B.; Henderson, D.J. Non–cell-autonomous roles for the planar cell polarity gene Vangl2 in development of the coronary circulation. Circ. Res. 2008, 102, 615–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etheridge, S.L.; Ray, S.; Li, S.; Hamblet, N.S.; Lijam, N.; Tsang, M.; Greer, J.; Kardos, N.; Wang, J.; Sussman, D.J.; et al. Murine dishevelled 3 functions in redundant pathways with dishevelled 1 and 2 in normal cardiac outflow tract, cochlea, and neural tube development. PLoS Genet. 2008, 4, e1000259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torban, E.; Patenaude, A.M.; Leclerc, S.; Rakowiecki, S.; Gauthier, S.; Andelfinger, G.; Epstein, D.J.; Gros, P. Genetic interaction between members of the Vangl family causes neural tube defects in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 3449–3454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandenberg, A.L.; Sassoon, D.A. Non-canonical Wnt signaling regulates cell polarity in female reproductive tract development via van gogh-like 2. Development 2009, 136, 1559–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VanderVorst, K.; Hatakeyama, J.; Berg, A.; Lee, H.; Carraway, I.I.I.K.L. Cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying planar cell polarity pathway contributions to cancer malignancy. In Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; Volume 81, pp. 78–87. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.S.; Lin, X.; Chan, T.F.; Chan, H.Y. Pan-cancer investigation reveals mechanistic insights of planar cell polarity gene Fuz in carcinogenesis. Aging 2021, 13, 7259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyberg, C.; Papachristou, P.; Haug, B.H.; Lagercrantz, H.; Kogner, P.; Ringstedt, T.; Wickström, M.; Johnsen, J.I. Planar cell polarity gene expression correlates with tumor cell viability and prognostic outcome in neuroblastoma. BMC Cancer 2016, 16, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, B.K.; Yoo, H.I.; Kim, I.; Park, J.; Yoon, S.K. FZD6 expression is negatively regulated by miR-199a-5p in human colorectal cancer. BMB Rep. 2015, 48, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corda, G.; Sala, G.; Lattanzio, R.; Iezzi, M.; Sallese, M.; Fragassi, G.; Lamolinara, A.; Mirza, H.; Barcaroli, D.; Ermler, S.; et al. Functional and prognostic significance of the genomic amplification of frizzled 6 (FZD6) in breast cancer. J. Pathol. 2017, 241, 350–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakoli, K.; Pour-Aboughadareh, A.; Kianersi, F.; Poczai, P.; Etminan, A.; Shooshtari, L. Applications of CRISPR-Cas9 as an advanced genome editing system in life sciences. BioTech 2021, 10, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Karakikes, I. Translating genomic insights into cardiovascular medicine: Opportunities and challenges of CRISPR-Cas9. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 31, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.Y.; Hu, H.B.; Cheng, Y.X.; Lu, X.J. CRISPR in medicine: Applications and challenges. Brief. Funct. Genom. 2020, 19, 151–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, S.; Wei, X.; Sheng, Z.; Hu, P.; Tang, S. CRISPR/Cas9 for development of disease resistance in plants: Recent progress, limitations and future prospects. Brief. Funct. Genom. 2020, 19, 26–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, T.; Ali, Q.; Rashid, M.S.; Malik, A. The journey of CRISPR-Cas9 from bacterial defense mechanism to a gene editing tool in both animals and plants. Biol. Clin. Sci. Res. J. 2020, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basta, L.P.; Sil, P.; Jones, R.A.; Little, K.A.; Hayward-Lara, G.; Devenport, D. Celsr1 and Celsr2 exhibit distinct adhesive interactions and contributions to planar cell polarity. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 10, 1064907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozak, E.L. Studies of the Planar Bipolar Epithelium of Zebrafish Neuromasts. Ph.D. Thesis, Technische Universität München, München, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey, I.I.G.W. Characterizing the Role of Key Planar Cell Polarity Pathway Components in Axon Guidance. Master’s Thesis, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Humphries, A.C.; Narang, S.; Mlodzik, M. Mutations associated with human neural tube defects display disrupted planar cell polarity in Drosophila. Elife 2020, 9, e53532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaffe, K.M.; Grimes, D.T.; Schottenfeld-Roames, J.; Werner, M.E.; Ku, T.S.; Kim, S.K.; Pelliccia, J.L.; Morante, N.F.; Mitchell, B.J.; Burdine, R.D. c21orf59/kurly controls both cilia motility and polarization. Cell Rep. 2016, 14, 1841–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.S.; Li, L.; Peng, S.; Chen, F.M.; Zhang, Q.; An, Y.; Lin, X.; Li, W.; Koon, A.C.; Chan, T.F.; et al. Planar cell polarity gene Fuz triggers apoptosis in neurodegenerative disease models. EMBO Rep. 2018, 19, e45409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voutsadakis, I.A. Molecular Alterations and Putative Therapeutic Targeting of Planar Cell Polarity Proteins in Breast Cancer. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, B.; Freitas, A.E.; Gorodetski, L.; Wang, J.; Tian, R.; Lee, Y.R.; Grewal, A.S.; Zou, Y. Planar cell polarity signaling components are a direct target of β-amyloid–associated degeneration of glutamatergic synapses. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabh2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, P.N.; Taylor, J.; Charlton, J. The domineering non-autonomy of frizzled and van Gogh clones in the Drosophila wing is a consequence of a disruption in local signaling. Mech. Dev. 2000, 96, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.; Adler, P.N. The function of the frizzled pathway in the Drosophila wing is dependent on inturned and fuzzy. Genetics 2002, 160, 1535–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strutt, D.; Johnson, R.; Cooper, K.; Bray, S. Asymmetric localization of frizzled and the determination of notch-dependent cell fate in the Drosophila eye. Curr. Biol. 2002, 12, 813–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casal, J.; Lawrence, P.A.; Struhl, G. Two separate molecular systems, Dachsous/Fat and Starry night/Frizzled, act independently to confer planar cell polarity. Development 2006, 133, 4561–4572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repiso, A.; Saavedra, P.; Casal, J.; Lawrence, P.A. Planar cell polarity: The orientation of larval denticles in Drosophila appears to depend on gradients of Dachsous and Fat. Development 2010, 137, 3411–3415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Drosophila | Vertebrates | Type of Protein |

|---|---|---|

| Fz (Frizzled) | Fz3, Fz2, Fz7, Fz6 | Extracellular-rich cysteine domain, |

| VII-pass trans-membrane receptor | ||

| Stan/Fmi (Starry night/Flamingo) | Celsr3, Celsr2, and Celsr1 | VII-pass trans-membrane receptor, |

| Extracellular cadherin-repeat | ||

| Pk (Prickle) | Pk2 and Pk1 | PET-domain, Triple-LIM domains, |

| Cytoplasmic | ||

| Dsh (Dishevelled) | Dvl3, Dvl1, and Dvl2 | PDZ, DIX, DEP, Cytoplasmic domains |

| Vang Gogh/Strabismus | Vangl2 and Vangl1 | PDZ-binding domains, IV-pass |

| Trans-membrane receptor | ||

| Dgo (Diego) | Inv (Inversin) | Ankyrin-repeats, Cytoplasmic |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kacker, S.; Parsad, V.; Singh, N.; Hordiichuk, D.; Alvarez, S.; Gohar, M.; Kacker, A.; Rai, S.K. Planar Cell Polarity Signaling: Coordinated Crosstalk for Cell Orientation. J. Dev. Biol. 2024, 12, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/jdb12020012

Kacker S, Parsad V, Singh N, Hordiichuk D, Alvarez S, Gohar M, Kacker A, Rai SK. Planar Cell Polarity Signaling: Coordinated Crosstalk for Cell Orientation. Journal of Developmental Biology. 2024; 12(2):12. https://doi.org/10.3390/jdb12020012

Chicago/Turabian StyleKacker, Sandeep, Varuneshwar Parsad, Naveen Singh, Daria Hordiichuk, Stacy Alvarez, Mahnoor Gohar, Anshu Kacker, and Sunil Kumar Rai. 2024. "Planar Cell Polarity Signaling: Coordinated Crosstalk for Cell Orientation" Journal of Developmental Biology 12, no. 2: 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/jdb12020012

APA StyleKacker, S., Parsad, V., Singh, N., Hordiichuk, D., Alvarez, S., Gohar, M., Kacker, A., & Rai, S. K. (2024). Planar Cell Polarity Signaling: Coordinated Crosstalk for Cell Orientation. Journal of Developmental Biology, 12(2), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/jdb12020012