Abstract

This paper describes a novel autonomous ground vehicle that is designed for exploring unknown environments which contain sources of ionising radiation, such as might be found in a nuclear disaster site or a legacy nuclear facility. While exploring the environment, it is important that the robot avoids radiation hot spots to minimise breakdowns. Broken down robots present a real problem: they not only cause the mission to fail but they can block access routes for future missions. Until now, such robots have had no autonomous gamma radiation avoidance capabilities. New software algorithms are presented that allow radiation measurements to be converted into a format in which they can be integrated into the robot’s navigation system so that it can actively avoid receiving a high radiation dose during a mission. An unmanned ground vehicle was fitted with a gamma radiation detector and an autonomous navigation package that included the new radiation avoidance software. The full system was evaluated experimentally in a complex semi-structured environment that contained two radiation sources. In the experiment, the robot successfully identified both sources and avoided areas that were found to have high levels of radiation while navigating between user defined waypoints. This advancement in the state-of-the-art has the potential to deliver real benefit to the nuclear industry, in terms of both increased chance of mission success and reduction of the reliance on human operatives to perform tasks in dangerous radiation environments.

Keywords:

nuclear; autonomous; costmap; 3D navigation; radiation detector; field robotics; experimental 1. Introduction

In nuclear facilities, there is often a need to explore and characterise an environment that has constrained access due to the risk posed by extreme levels of radiation exposure. Characterisation often involves, but is not limited to: camera surveys, LiDAR scans, measuring radiation levels and identifying locations of radiation hot spots. The unknown environment could be an aging legacy facility that must be characterised prior to decommissioning, such as at Sellafield in the UK, or an active facility following a nuclear incident, such as Fukushima Daiichi in 2011 or Chernobyl in 1986. Robotic systems offer an ideal solution for exploring these environments as they remove the need for humans to access dangerous areas. However, it is essential that these robots do not fail during a mission. Broken down robots can block access routes and make cleanup tasks even more difficult [1]. Exposure to gamma radiation has a damaging effect on electronic systems and the severity of this damage is related to the total ionising dose (TID) that the electronic system receives [2]. The precise impact of gamma radiation on the electronic devices is stochastic to a certain extent and hence robot breakdowns due to exposure will be unpredictable. Robots can be built using radiation hardened components; however the range of components is very limited and their cost is often several orders of magnitude higher than standard components [3]. Radiation hardening also causes drawbacks in terms of the robot’s performance and battery life, due to the limited selection of components and the extra mass [4]. Moreover, irrespective of the level of radiation hardening, avoiding radiation hot-spots will always decrease the chance of robot breakdowns. In any decommissioning or clean-up environment there will be areas with high and low radioactivity levels; therefore paths can be taken that minimise the radiation dose received by the robot, helping to extend its life. The motivation of this work is to reduce robot breakdowns by planning and following paths that minimise the radiation dose received by the robot.

Time spent navigating close to gamma sources is a key factor in minimising the dose received by the robot. For an operator driving a robot, careful consideration of live radiation measurements and planning routes appropriately is generally not a practical method of minimising the dose received by the robot, due to the decision time. The robot will most likely be receiving some level of radiation dose throughout the whole mission so any time spent making decisions will increase the total dose received. Therefore, using autonomous path planning that makes fast, evidencebased decisions to help the robot avoid radiation can increase the lifespan of the robot and the chance of mission success. The radiation detector used on the robot is a standard ThermoFisher RadEye unit that is widely available and commonly used. The detector is not collimated so has no directional sensitivity; this means that the robot can only report radiation intensity at its current location. The effect of this is that the robot does not avoid radiation the first time it encounters it. Rather, the robot detects regions of high radiation as it passes through them and then avoids these regions for the rest of the mission, reducing the overall dose that the robot receives. The reason that this was selected as the most appropriate solution is because there is an inherent latency in gamma radiation detectors due to the stochastic nature of radioactive decay and the subsequent requirement for there to be an integration time for a dose rate to be calculated. The latency means that directional radiation detection and prediction of the radiation field in regions ahead of the robot is not practical because with a latency of 8 s and typical speed of 1 m/s the robot could travel 8 m towards a source before a high reading is measured and can be accounted for by the navigation. Therefore, if the robot was to predict radiation ahead of its arrival so that it could be avoided on the first pass, the robot velocity would need to be decreased to an impractical level that would increase the overall dose due to the extended mission time and background dose. The setup demonstrated in this paper is a practical method that can reduce the overall dose a robot receives using readily available commercial sensors.

The navigation software that was used as the basis for the work was CSIRO’s experimental navigation stack, which is currently under development as part of the DARPA Subterranean Challenge [5]. Although the navigation stack is being developed prioritising autonomous behaviours in communications constrained unknown environments, the work performed in this paper highlights its versatility and modularity with respect to existing out-of-the-box solutions such as the ROS navigation stack [6].

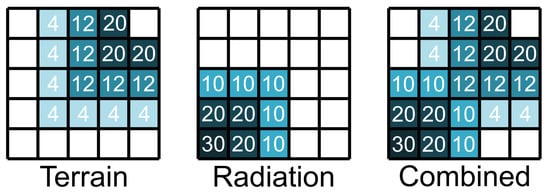

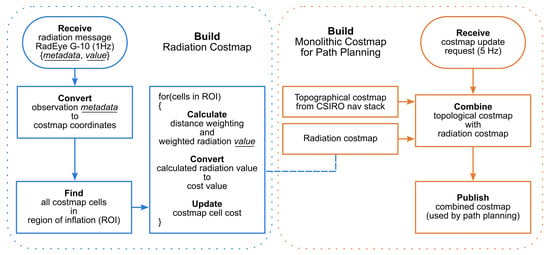

Additional software packages were written to give the robot real-time radiation avoidance functionality. The first package written builds a 2D costmap using the position stamped radiation measurements from the onboard Gamma detector and the second package integrates the new 2D costmap into the robot’s existing costmap. The new algorithms were experimentally validated on a real robot using safe (non-ionising) radiation sources. The robot operated in a complex 3D environment and a 3D voxel map of the geographic area was produced alongside a 2.5D radiation map. The robot was guided at a high level by a user placing waypoints; navigation between waypoints and radiation avoidance was handled by the robot’s autonomy package.

More specifically, novel contributions of the work presented in this paper are as follows:

- An online method of generating a variable value radiation costmap from nonuniform point measurements of radiation and integration of this costmap into an existing costmap based navigation stack.

- Experimental verification that our unmanned ground vehicle (UGV) can autonomously avoid gamma radiation in real-time, while exploring unknown environments.

- Experimental verification that CSIRO’s Navigation Pack and accompanying experimental navigation stack can navigate obstacles and topography in varied and complex environments.

In the literature, both ground and aerial robots have been used to produce location tagged nuclear radiation data, with varying levels of sophistication in terms of autonomy and radiation mapping ability. Many of the robots and systems used to date were developed in response to the Fukushima Daiichi incident in 2011.

Nagatani [7] discusses the ground vehicles that were sent onto the Fukushima Daiichi site following the incident in 2011. They were remotely operated and the radiation detectors were not integrated into the software; the dosimeter measurement was observed using a camera pointed at the readout.

Multirotor unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) were developed to improve the resolution of contamination monitoring on the Fukushima site. In [8], MacFarlane et al. presented a system comprising a LiDAR, GPS module and a gamma spectrometer, which is capable of transmitting georeferenced radiation measurements in realtime. In [8,9], radiation was presented on a 2D map and in a later publication [10], Martin et al. collected and rendered a 3D radiation map of stepped farmland in the Kawamata region of Fukushima.

In a series of recent works including [11,12,13], Vetter et al. furthered the stateoftheart in realtime mapping of nuclear radiation by developing a multi-sensor instrument that can map a local area and fuse scene data with nuclear radiation data.

Although the research area is well developed in terms of mapping of gamma radiation sources, the use of robot autonomy in the data collection is uncommon. None of the work cited thus far includes autonomous navigation that is influenced by the radiation measurement. The more advanced schemes have automated coverage [14], or human-in -the-loop waypoint navigation [15]. Work in the area of radiationinfluenced autonomous navigation is limited. In [16], Li et al. present a UAV that can autonomously search for a radiation source. Three different search algorithms are suggested, but field tests did not incorporate automated searching as their UAV had no means of localisation. In [17], Cortez et al. use a Bayesian-based strategy to alter the amount of time that the robot spends in each cell of a square gridded search area and control measurement uncertainty. In [18], Bird et al. describe the design and development of an autonomous, groundbased, alpha radiation monitoring robot named CARMA. The CARMA robot was unique in its ability to autonomously monitor for alpha radiation and because its navigation algorithms took account of the radiation measurements. Alpha radiation can be stopped by a few cm of air, therefore CARMA needed to be in close physical proximity to the radiation source to detect it. When contamination was detected, CARMA reversed and added a synthetic obstacle to its map. This method worked well for ground level alpha contamination that can be classed as present or not present, but is not suited to highly penetrative gamma radiation with varying intensity.

Outside of the radiation monitoring field, the use of additional information to improve the navigation scheme of an autonomous robot is common. For example, Sebastian and Pinhas [19] developed a path planning method for a tracked vehicle that takes into account information such as slip, slope of terrain and actuator limitations. In [20], an energy requirement costmap was generated for a UAV and used to increase flight times.

2. Hardware Architecture

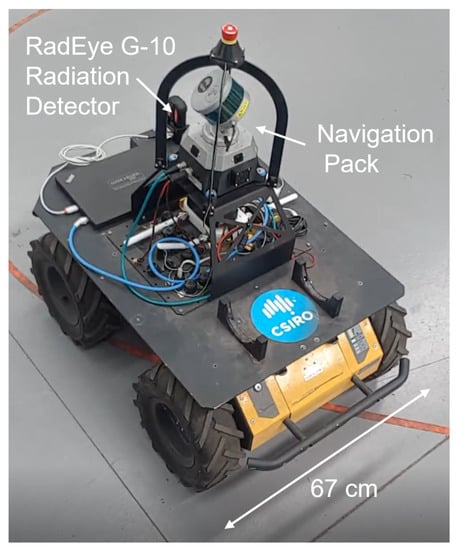

The UGV used for all experimental work presented in this paper was a modified Clearpath Husky [21], shown in Figure 1. The equipment added to the offtheshelf platform was: a CSIRO Navigation Pack, a Thermo Fischer RadEye G-10 personal gamma dosimeter with a laptop for communicating with the dosimeter, and a Rajant BreadCrumb ES1 communication node to increase the wireless range with the operator base station.

Figure 1.

The modified Clearpath Husky robot equipped with CSIRO’s Navigation Pack and a RadEye G-10 personal dosimeter.

The CSIRO Navigation Pack (also known as “CatPack” [22]) is a selfcontained 2.5D localisation and navigation solution for ground vehicles. Its sensor suite comprises a Velodyne Puck (VLP16) LiDAR, a LORD Microstrain CV525 Attitude and Heading Reference System (AHRS), four RGB cameras with wide angle lenses to visually cover the full 360 of the robot’s plane as well as LED lights to operate in underground environments. The Pack contains an NVIDIA Jetson AGX Xavier and an Intel NUC as the main sources of computational power to perform all the perception and navigation tasks. The Pack commands the Husky by sending velocity commands to the internal robot computer and is powered using the Husky internal batteries.

The G-10 dosimeter streams single value gamma radiation measurements to a laptop at 1 Hz. The laptop records the live measurements, geographically tags them in 3D space and makes the information available for the radiation avoidance software. Although the dosimeter provides radiation readings at a rate of 1 Hz, the measurement has a latency of approximately 8 s between a spike in radiation hitting the device and a spike in the value output by the device. This is due to the dosimeter averaging readings over a time history, with the aim of smoothing the noisy nature of radiation readings caused by the stochastic nature of radioactive decay.

5. Experimental Validation

5.1. Experiment Setup

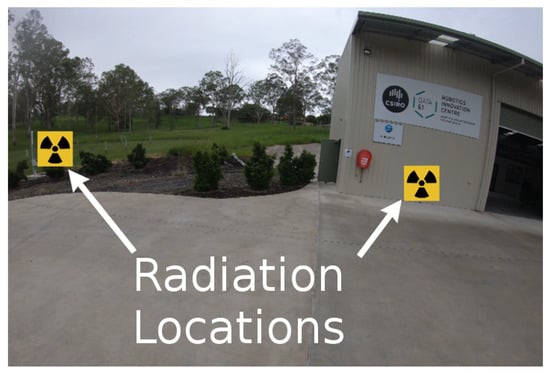

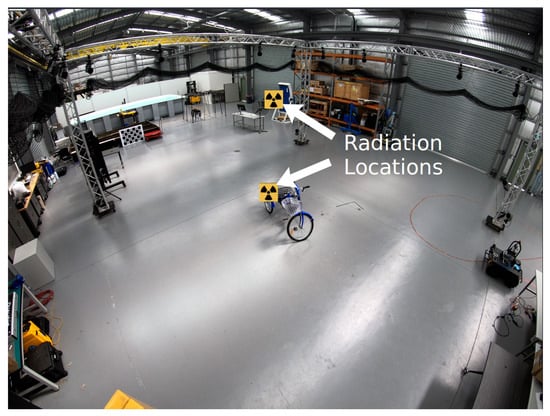

The CSIRO Navigation Pack and the real-time radiation avoidance functionality that was added to the CSIRO navigation stack was evaluated in two experiments. In both experiments the robot started at the same location inside a warehouse. In the first experiment the robot left the building and explored outside the warehouse and in the second experiment the robot was exclusively navigating inside. Figure 4 and Figure 5 show the environments that were used for the first and second experiments relatively. The first environment was semi-structured and comprised a paved loading area, an area of small bushes and an area of sloped grass. It included significant topography, many structured and unstructured obstacles and loose terrain. This varied and complex environment was selected to fully test the capabilities of the robot, in terms of both its radiation avoidance functionality and the ability of the CSIRO navigation stack to operate in a challenging environment. The second environment was the inside of a warehouse that is used for robot testing and contained a variety of obstacles such as other robots, a camera rig, a trike, office furniture and storage racks. The environment was used as it was found at the time of the testing. Neither of the environments were sanitised for the experiments and no modifications were made to the robot between the experiments. GPS is not required by the Navigation Pack for localisation and was not used in either experiment.

Figure 4.

Photograph of outdoor test environment 1, highlighting radiation source locations.

Figure 5.

Photograph of indoor test environment 2, highlighting radiation source locations.

The robot’s missions were controlled by an operator placing waypoints in the online generated 3D voxel map through Goto commands. Although higher levels of autonomy such as frontiers exploration were available, Goto waypoint navigation was considered to be the most suited to the task, because in a real-world situation, a human operator would almost certainly be kept in the loop when exploring unknown radiation environments. Using waypoint navigation, the operator has top level control of the mission, while the robot’s autonomous capabilities take care of lower level navigation challenges. This allows the operator mental capacity for higher level decision making such as choosing areas to explore and deciding when to return to base.

To simulate a gamma radiation source, two STS Safe-MiniSources [31] were placed in each environment, in the locations shown in Figure 4 and Figure 5. The Safe-MiniSources emit radio-frequency radiation and the RadEye G-10 on the robot was a modified unit [32] that had been converted to detect radio-frequency radiation rather than gamma radiation. A software package (ROS node) was produced to allow communication between the RadEye G-10 and a computer (the RadEye ROS node is on GitHub and available for use; please contact the corresponding author for access). To change the setup so that it would work in a real gamma radiation environment, the modified RadEye G-10 would simply need to be swapped for a standard RadEye G-10, commonly used in the nuclear industry.

To account for the fact that the RadEye G-10 has a latency of approximately 8 s, as radiation measurements arrive, they are shifted backwards so that they are associated with the location the robot was in, 8 s previously. This causes the radiation costmap update to tail the robot’s location.

For the experimental work, the following constants (defined in Section 4) were used: m, m, m, , . No radiation scale is attached to any of the results because radiation levels in the environment were set by the Safe-MiniSources which are uncalibrated and do not emit gamma radiation.

It is important to note that from the robot’s perspective the environments were both completely unknown: the robot had no prior information about the environments, such as a geographic or radiation map, these were built during the mission.

5.2. Results of Experiment 1

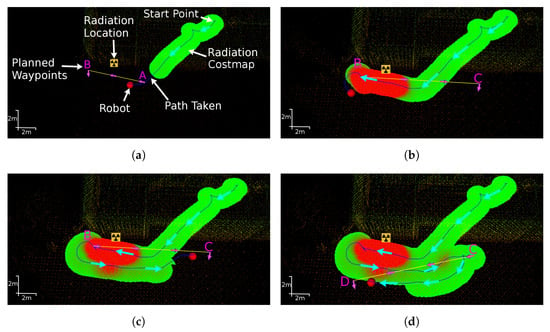

Figure 6 shows the robot navigating from the start point to each of the first four waypoints. The four images, (a) to (d), represent successive instances in time during the experiment. In each image, the global voxel map is shown, with the radiation costmap and robot’s path overlaid. With reference to Figure 6, the robot navigated from its start position inside the warehouse through the open roller door to waypoint A outside. In Figure 6a the robot is travelling between waypoints A and B and the radiation costmap laid out behind the robot is apparent. While moving from A to B, the robot passed one of the Safe-MiniSources that was placed outside against the warehouse wall. In Figure 6b the costmap shows the area of high radiation (and therefore cost) that was caused by passing close to the radiation source. In Figure 6c the path that was taken from B to C is shown and it is evident that the robot did not take the direct path (the yellow line) from B to C, rather the robot’s path planner navigated around the area of high radiation that it measured. Finally, in Figure 6d the path taken from waypoint C to D is shown; here the robot takes a curved trajectory (instead of the straight yellow line) that avoids the higher radiation levels that it measured on its path from B to C.

Figure 6.

Images showing the global voxel maps and the radiation costmap layer at four time instances during the first experiment where the robot was navigating outside. In the radiation costmap, increasing radiation is represented by green for low cost fading to red for high cost. (a) Navigating from waypoint A to B. (b) Navigating from waypoint B to C. (c) Navigating from waypoint B to C via an indirect path. (d) Navigating from waypoint C to D.

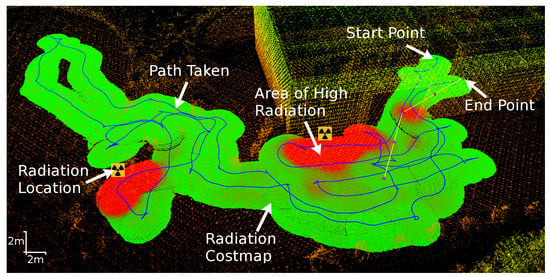

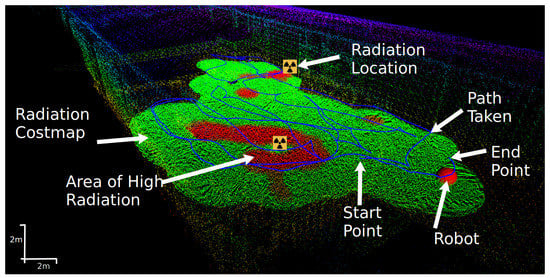

In Figure 7, the full mission path and radiation costmap is plotted over the final global voxel map. During the mission, the robot successfully identified and then subsequently avoided the two areas surrounding the radiation sources. The robot also successfully navigated in both an indoor and an outdoor environment and in challenging, varied terrain that contained multiple obstacles including walls, doorways and bushes. Twice during the mission, high levels of radiation caused a region of high cost (red) to engulf the robot and recovery behaviours were automatically triggered to move the robot out of the area of high cost.

Figure 7.

Image showing data captured during the first experiment where the robot was navigating in a complex outdoor environment. During the mission, the robot successfully identifies and then avoids two radiation sources.

In Figure 7, there are some areas showing high levels of radiation that were not near the two sources placed in the environment. It is important to note that the Safe-MiniSources operate in the RF band and will therefore not behave exactly as gamma radiation. Higher than expected sensor readings in some locations may have been caused by multipath propagation or the sensor receiving spurious readings from other equipment.

The full experiment run is best observed in the accompanying video that shows time-synced views of the global map, the local costmap and a video stream of the environment.

5.3. Results of Experiment 2

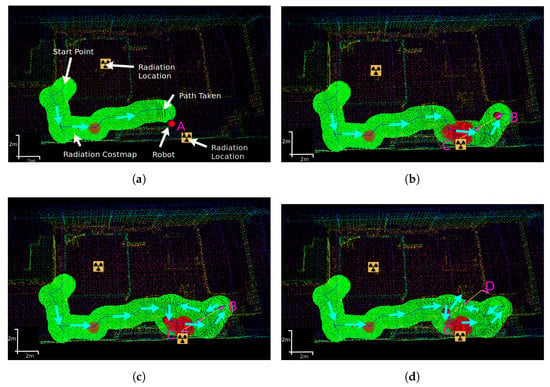

Figure 8 shows the robot’s indoor navigation for the first four placed waypoints in experiment 2. In Figure 8a the robot navigates successfully to the first waypoint but does detect some higher levels of radiation at an unexpected location. This was assumed to be due to multipath effects as described above. In Figure 8b the robot is at waypoint A and was asked by the operator to move to waypoint C which is near a radiation source and had been identified by the robot as being in a high dose rate area. In Figure 8c the robot attempts to navigate around the high radiation region to get to waypoint C and in Figure 8d the robot rejected waypoint C due to the high dose rate in its vicinity and moves on to the next waypoint.

Figure 8.

Images showing the global voxel maps and the radiation costmap layer at four time instances during the second indoor experiment. The sequence shows a waypoint being rejected due the fact that it is in a high dose rate region. In the radiation costmap, increasing radiation is represented by green for low cost fading to red for high cost. (a) Navigating to waypoint A prior to radiation detection. (b) Request to navigate from waypoint B to C. (c) Attempt to navigate around radiation to waypoint C. (d) Waypoint C rejected as inaccessible.

Figure 9 is analogous to Figure 7 and shows the full indoor mission path and radiation map plotted over the final voxel map. The robot navigated the indoor environment successfully and identified both radiation sources. It appeared that the effects of multipath from the radiation sources is stronger inside than outside as several regions away from the sources were identified as having a high dose rate. However, this does not detract from the efficacy of the radiation informed navigation system and is most likely to be a feature of the simulated radiation sources as opposed to an effect that might be expected with real gamma sources.

Figure 9.

Image showing data captured during the second experiment where the robot was navigating indoors. The robot successfully navigated around the confined environment and identified then avoided both radiation sources.

6. Conclusions

The research presented has made an important step forward in mobile robot autonomy for the nuclear sector. A method for generating a radiation costmap and combining this with an existing costmap was developed and presented. Using the new combined costmap, the robot was given the added functionality of being able to navigate around and actively remove itself from areas of high radiation that were detected during the mission.

The full system was validated in two unknown environments on a real robot using safe radiation sources. The experiment results demonstrated that the new radiation avoidance software functions properly: the robot clearly detects and then subsequently avoids areas with high radiation levels when they are available in the costmap. The costmaps produced are appropriate for the navigation stack and facilitate smooth and well-reasoned navigation. The results not only show the successful addition of real-time radiation avoidance, but also demonstrate the efficacy of the CSIRO Navigation stack in complex indoor and outdoor environments that contain significant topography and a variety of obstacles and ground conditions.

This increased level of robot autonomy has the potential to provide real benefit for the nuclear sector. Fast, evidence-based decisions can be made by the robot that reduce the radiation dose it receives during a mission in an unknown nuclear environment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.G. and A.W.; methodology, K.G. and E.H.; software, K.G. and T.W.; validation, K.G. and E.H.; resources, B.L. and E.H.; data curation, T.W.; writing—original draft preparation, K.G., E.H., T.W. and A.W.; writing—review and editing, B.L. and A.W.; visualization, T.W.; supervision, E.H. and B.L.; project administration, B.L.; funding acquisition, B.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council under grants: EP/P01366X/1, EP/R026084/1 and EP/P018505/1.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would also like to thank the CSIRO Robotics and Autonomous Systems Group for the in kind support provided for this work, specially to Thomas Hines for helping with the software setup on the robotic platform and Paul Flick for facilitating the secondment.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Tsitsimpelis, I.; Taylor, C.J.; Lennox, B.; Joyce, M.J. A review of ground-based robotic systems for the characterization of nuclear environments. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2019, 111, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nancekievill, M.; Jones, A.; Joyce, M.; Lennox, B.; Watson, S.; Katakura, J.; Okumura, K.; Kamada, S.; Katoh, M.; Nishimura, K. Development of a radiological characterization submersible rov for use at fukushima daiichi. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2018, 65, 2565–2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houssay, L.P. Robotics and Radiation Hardening in the Nuclear Industry. Master’s Thesis, University of Florida, Gainsville, FL, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ducros, C.; Hauser, G.; Mahjoubi, N.; Girones, P.; Boisset, L.; Sorin, A.; Jonquet, E.; Falciola, J.M.; Benhamou, A. RICA: A tracked robot for sampling and radiological characterization in the nuclear field. J. Field Robot. 2017, 34, 583–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DARPA Subterranean Challenge. Available online: https://www.subtchallenge.com/ (accessed on 10 October 2020).

- Marder-Eppstein, E.; Berger, E.; Foote, T.; Gerkey, B.; Konolige, K. The Office Marathon: Robust Navigation in an Indoor Office Environment. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Anchorage, AK, USA, 3–7 May 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nagatani, K.; Kiribayashi, S.; Okada, Y.; Otake, K.; Yoshida, K.; Tadokoro, S.; Nishimura, T.; Yoshida, T.; Koyanagi, E.; Fukushima, M.; et al. Emergency response to the nuclear accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plants using mobile rescue robots. J. Field Robot. 2013, 30, 44–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacFarlane, J.; Payton, O.; Keatley, A.; Scott, G.; Pullin, H.; Crane, R.; Smilion, M.; Popescu, I.; Curlea, V.; Scott, T. Lightweight aerial vehicles for monitoring, assessment and mapping of radiation anomalies. J. Environ. Radioact. 2014, 136, 127–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, P.G.; Payton, O.D.; Fardoulis, J.S.; Richards, D.A.; Yamashiki, Y.; Scott, T.B. Low altitude unmanned aerial vehicle for characterising remediation effectiveness following the FDNPP accident. J. Environ. Radioact. 2016, 151, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, P.G.; Kwong, S.; Smith, N.T.; Yamashiki, Y.; Payton, O.D.; Russell-Pavier, F.S.; Fardoulis, J.S.; Richards, D.A.; Scott, T.B. 3D unmanned aerial vehicle radiation mapping for assessing contaminant distribution and mobility. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2016, 52, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetter, K.; Barnowski, R.; Cates, J.W.; Haefner, A.; Joshi, T.H.Y.; Pavlovsky, R.; Quiter, B.J. Advances in nuclear radiation sensing: Enabling 3-D gamma-ray vision. Sensors 2019, 19, 2541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vetter, K.; Barnowksi, R.; Haefner, A.; Joshi, T.H.; Pavlovsky, R.; Quiter, B.J. Gamma-Ray imaging for nuclear security and safety: Towards 3-D gamma-ray vision. Nucl. Instruments Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A Accel. Spectrometers Detect. Assoc. Equip. 2018, 878, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellfeld, D.; Barton, P.; Gunter, D.; Haefner, A.; Mihailescu, L.; Vetter, K. Real-Time Free-Moving Active Coded Mask 3D Gamma-Ray Imaging. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2019, 66, 2252–2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosmar, M.E.; Nokleby, S.B.; Waller, E. Experimental testing of an autonomous radiation mapping robot. In Proceedings of the 2017 CCToMM M3 Symposium, Montreal, QC, Canada, 25–26 May 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Royo, P.; Pastor, E.; Macias, M.; Cuadrado, R.; Barrado, C.; Vargas, A. An unmanned aircraft system to detect a radiological point source using RIMA software architecture. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, C.; Peng, Z.R.; Ge, L. Use of multi-rotor unmanned aerial vehicles for radioactive source search. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortez, R.A.; Papageorgiou, X.; Tanner, H.G.; Klimenko, A.V.; Borozdin, K.N.; Lumia, R.; Priedhorsky, W.C. Smart radiation sensor management. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 2008, 15, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, B.; Griffiths, A.; Martin, H.; Codres, E.; Jones, J.; Stancu, A.; Lennox, B.; Watson, S.; Poteau, X. A Robot to Monitor Nuclear Facilities: Using Autonomous Radiation-Monitoring Assistance to Reduce Risk and Cost. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 2018, 26, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastian, B.; Ben-Tzvi, P. Physics based path planning for autonomous tracked vehicle in challenging terrain. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2019, 95, 511–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarty, A.; Langelaan, J.W. Energy-based long-range path planning for soaring-capable unmanned aerial vehicles. J. Guid. Control. Dyn. 2011, 34, 1002–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husky Unmanned Ground Vehicle. Available online: https://clearpathrobotics.com/husky-unmanned-ground-vehicle-robot/ (accessed on 2 October 2020).

- Hines, T.; Stepanas, K.; Talbot, F.; Sa, I.; Lewis, J.; Hernandez, E.; Kottege, N.; Hudson, N. Virtual Surfaces and Attitude Aware Planning and Behaviours for Negative Obstacle Navigation. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2021, 6, 4048–4055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosse, M.; Zlot, R. Continuous 3D scan-matching with a spinning 2D laser. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Kobe, Japan, 12–17 May 2009; pp. 4312–4319. [Google Scholar]

- Bosse, M.; Zlot, R.; Flick, P. Zebedee: Design of a Spring-Mounted 3-D Range Sensor with Application to Mobile Mapping. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2012, 28, 1104–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CSIRO Data61 Robotics and Autonomous Systems. Occupancy Homogeneous Map. Available online: https://github.com/csiro-robotics/ohm (accessed on 24 May 2021).

- Dolgov, D.; Thrun, S.; Montemerlo, M.; Diebel, J. Path Planning for Autonomous Vehicles in Unknown Semi-structured Environments. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2010, 29, 485–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemec, D.; Gregor, M.; Bubeníková, E.; Hruboš, M.; Pirník, R. Improving the Hybrid A* method for a non-holonomic wheeled robot. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 2019, 16, 1729881419826857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.; Jiang, S.; OBrien, M.; Wagner, G.; Hernandez, E.; Cox, M.; Pitt, A.; Arkin, R.; Hudson, N. Online 3D Frontier-Based UGV and UAV Exploration Using Direct Point Cloud Visibility. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Multisensor Fusion and Integration, Karlsruhe, Germany, 14–16 September 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, D.V.; Hershberger, D.; Smart, W.D. Layered costmaps for context-sensitive navigation. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Chicago, IL, USA, 14–18 September 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoll, G.F. Radiation Detection and Measurement, 4th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- STS Safe Mini-Source Simulated Radiation Source. Available online: https://www.safetrainingsystems.com/safeminisource (accessed on 6 October 2020).

- STS Safe-RadEye G-10 Simulated Survey Meter. Available online: https://www.safetrainingsystems.com/safe-radeyeg10 (accessed on 7 October 2020).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).