Substance Use and Attendance Motives of Electronic Dance Music (EDM) Event Attendees: A Survey Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection and Inclusion Criteria

2.2. Measures

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

3.2. Substance Use

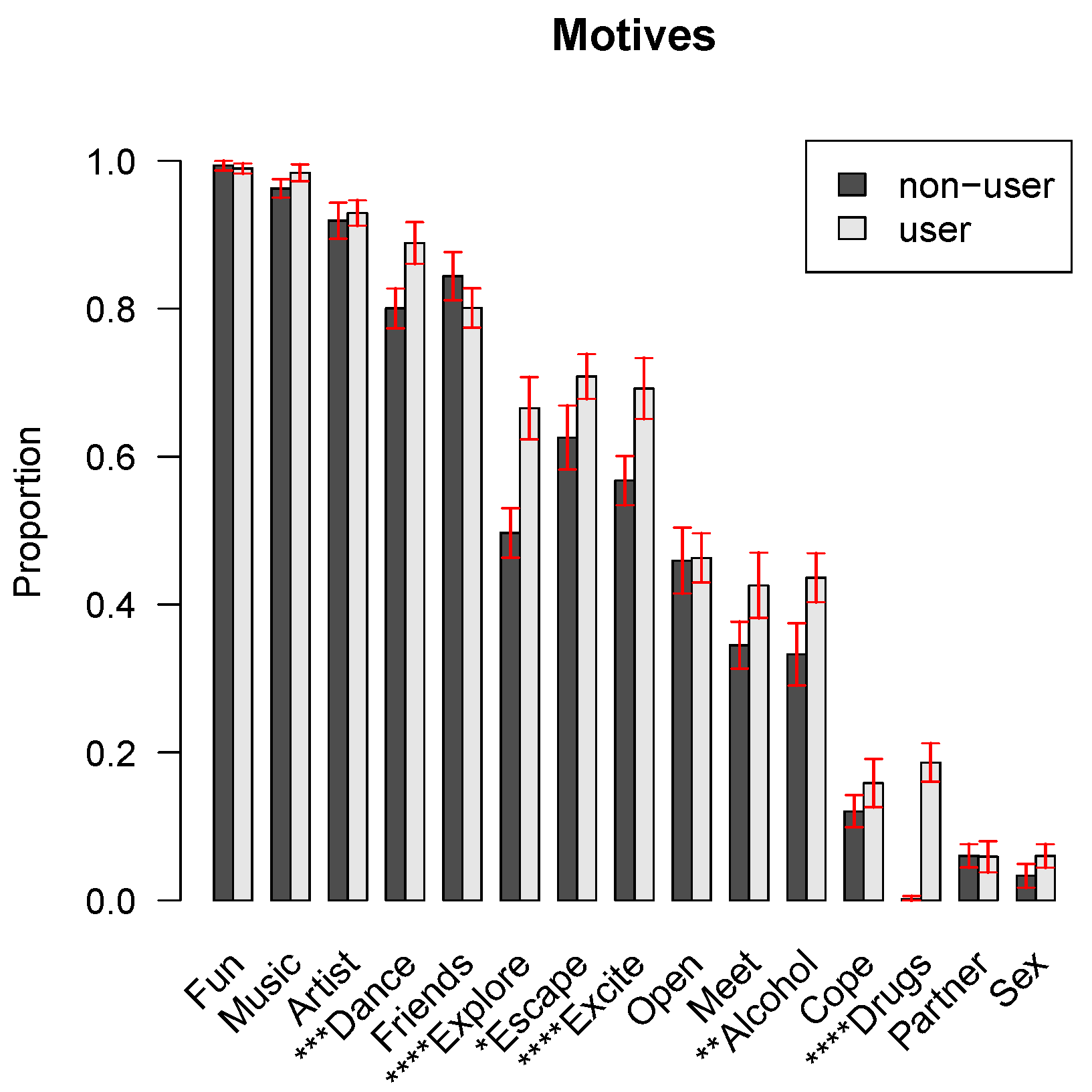

3.3. Attendance Motives

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lund, A.; Turris, S.A. Mass-gathering medicine: Risks and patient presentations at a 2-day electronic dance music event. Prehosp. Disaster Med. 2015, 30, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weir, E. Raves: A review of the culture, the drugs, and the prevention of harm. CMAJ 2000, 162, 1843–1848. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- John, G.S. Introduction: Dance music festivals and event-cultures. In Weekend Societies: Electronic Dance Music Festivals and Event-cultures; John, G.S., Ed.; Bloomsbury: London, UK, 2017; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Little, N.; Burger, B.; Croucher, S.M. EDM and Ecstasy: The lived experiences of electronic dance music festival attendees. J. New Music Res. 2017, 47, 78–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IMS Business Report 2019: An Annual Study of the Electronic Music Industry. Available online: https://www.internationalmusicsummit.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/IMS-Business-Report-2019-vFinal.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2022).

- Buckland, F. Impossible Dance: Club Culture and Queer World-Making, 1st ed.; Wesleyan University Press: Middletown, CT, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Electronic Dance Music (EDM) Fan Behavior Differs Greatly from that of Other Music Fans. Available online: https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2013/06/17/1334297/0/en/Electronic-Dance-Music-EDM-Fan-Behavior-Differs-Greatly-From-That-of-Other-Music-Fans.html (accessed on 15 November 2022).

- Kurtz, S.P.; Buttram, M.E.; Pagano, M.E.; Surratt, H.L. A randomized trial of brief assessment interventions for young adults who use drugs in the club scene. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2017, 78, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palamar, J.J.; Griffin-Tomas, M.; Ompad, D.C. Illicit drug use among rave attendees in a nationally representative sample of US high school seniors. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015, 152, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parsons, J.T.; Grov, C.; Kelly, B.C. Club drug use and dependence among young adults recruited through time-space sampling. Public Health Rep. 2009, 124, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanckaert, P.; Cannaert, A.; Van Uytfanghe, K.; Hulpia, F.; Deconinck, E.; Van Calenbergh, S.; Stove, C. Report on a novel emerging class of highly potent benzimidazole NPS opioids: Chemical and in vitro functional characterization of isotonitazene. Drug Test. Anal. 2020, 12, 422–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EMCDDA. New Psychoactive Substances (NPS). Publications Office of the European Union. 2020. Available online: https://www.emcdda.europa.eu/topics/nps_ro (accessed on 15 November 2022).

- German, C.L.; Fleckenstein, A.E.; Hanson, G.R. Bath salts and synthetic cathinones: An emerging designer drug phenomenon. Life Sci. 2014, 97, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musselman, M.E.; Hampton, J.E. “Not for human consumption”: A review of emerging designer drugs. Pharmacotherapy 2014, 34, 745–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, C.E.; Moxham-Hall, V.; Ritter, A.; Weatherburn, D.; MacCoun, R. The deterrent effects of Australian street-level drug law enforcement on illicit drug offending at outdoor music festivals. Int. J. Drug Policy 2017, 41, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krotulski, A.J.; Mohr, A.L.A.; Fogarty, M.F.; Logan, B.K. The detection of novel stimulants in oral fluid from users reporting ecstasy, Molly and MDMA ingestion. J. Anal. Toxicol. 2018, 42, 544–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramo, D.E.; Grov, C.; Delucchi, K.L.; Kelly, B.C.; Parsons, J.T. Cocaine use trajectories of club drug-using young adults recruited using time-space sampling. Addict. Behav. 2011, 36, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chhabra, N.; Gimbar, R.P.; Walla, L.M.; Thompson, T.M. Emergency department patient burden from an electronic dance music festival. J. Emerg. Med. 2018, 54, 435–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furr-Holden, D.; Voas, R.B.; Kelley-Baker, T.; Miller, B. Drug and alcohol-impaired driving among electronic music dance event attendees. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006, 85, 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.B.; Voas, R.S.; Miller, B.A.; Holder, H.D. Predicting drug use at electronic music dance events: Self-reports and biological measurements. Eval. Rev. 2009, 33, 211–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palamar, J.J.; Acosta, P.; Le, A.; Cleland, C.M.; Nelson, L.S. Adverse drug-related effects among electronic dance music party attendees. Int. J. Drug Policy 2019, 73, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palamar, J.J.; Le, A.; Acosta, P.; Cleland, C.M. Consistency of self-reported drug use among electronic dance music party attendees. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2019, 38, 798–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Havere, T.; Vanderplasschen, W.; Lammertyn, J.; Broekaert, E.; Bellis, M. Drug use and nightlife: More than just dance music. Subst. Abuse Treat. Prev. Policy 2011, 6, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Box, S.A.; Prescott, L.F.; Freestone, S. Hyponatremia at a rave. Postgrad. Med. J. 1997, 78, 53–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britt, G.C.; McCance-Katz, E.F. A brief overview of the clinical pharmacology of “club drugs”. Subst. Use Misuse 2005, 40, 1189–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.B.; Voas, R.B.; Miller, B.A. Driving decisions when leaving electronic music dance events: Driver, passenger, and group effects. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2012, 13, 577–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soomaroo, L.; Murray, V. Disasters at mass gatherings: Lessons from history. PLoS Curr. 2012, 4, RRN1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, R.V.; Venkatesh, M. A cognitive-motivational model of decision satisfaction. Instr. Sci. 2000, 28, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Attitude-behavior relations: A theoretical analysis and review of empirical research. Psychol. Bull. 1977, 84, 888–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnoth, J. Tourism motivation and expectation formation. Ann. Tour. Res. 1997, 21, 283–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, J.L. Motivations for pleasure vacation. Ann. Tour. Res. 1979, 6, 408–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, J.L.; McKay, S.L. Motives of visitors attending festival events. Ann. Tour. Res. 1997, 24, 425–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dann, G.M.S. Tourism motivation: An appraisal. Ann. Tour. Res. 1981, 8, 187–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manolika, M.; Baltzis, A.; Tsigilis, N. Measuring motives for cultural consumption: A review of the literature. Am. J. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 3, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Uysal, M.; Gahan, L.W.; Martin, B. An examination of event motivations: A case study. Festiv. Manag. Event Tour. 1993, 1, 5–10. [Google Scholar]

- Trail, G.T.; James, J.D. The motivation scale for sport consumption: Assessment of the scale’s psychometric properties. J. Sport Behav. 2001, 24, 108–127. [Google Scholar]

- Snepenger, D.; King, J.; Marshall, E.; Uysal, M. Modeling Iso-Ahola’s motivation theory in the tourism context. J. Travel Res. 2006, 45, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dann, G.M.S. Anomie, ego-enhancement and tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1977, 4, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, D.; Iso-Ahola, S.E. Leisure and health: The role of social support and self-determination. J. Leis. Res. 1993, 25, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iso-Ahola, S.E. Towards a social psychology theory of tourism motivation: A rejoinder. Ann. Tour. Res. 1982, 9, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, D. Festivals, Special Events and Tourism; Van Nostrand Reinhold: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Getz, D. Event tourism: Definition, evolution, and research. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 403–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, K. A Theory of human motivation by Abraham H. Maslow (1942). Br. J. Psychiatry 2016, 208, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abulof, U. Introduction: Why we deed Maslow in the twenty-first century. Society 2017, 54, 508–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansfeld, Y. From motivation to actual travel. Ann. Tour. Res. 1992, 19, 399–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinnicombe, T.; Sou, P.U.J. Socialization or genre appreciation: The motives of music festival participants. Int. J. Event Festiv. Man. 2017, 8, 274–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, H.; Daniels, M. Does the music matter? Motivations for attending a music festival. Event Manag. 2005, 9, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faulkner, B.; Fredline, E.; Larson, M.; Tomljenovic, R. A marketing analysis of Sweden’s storsjoyran music festival. Tour. Anal. 1999, 4, 157–171. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson, R.; Pearce, D.G. Why do people attend events: A comparative analysis of visitor motivations at four south island events. J. Travel Res. 2001, 39, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelder, G.; Robinson, P. A critical comparative study of visitor motivations for attending music festivals: A case study of Glastonbury and V Festival. Event Manag. 2009, 13, 181–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blešić, I.; Pivac, T.; Stamenkovic, I.; Besermenji, S. Motives of visits to ethno music festivals with regard to gender and age structure of visitors. Event Manag. 2013, 17, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-N.; Wood, E.H. Music festival motivation in China: Free the mind. Leis. Stud. 2014, 35, 332–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EMCDDA. European Drug Report 2020: Trends and Developments; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Waldron, J.; Grabski, M.; Freeman, T.P.; Mokrysz, C.; Hindocha, C.; Measham, F.; van Beek, R.; van der Pol, P.; Hauspie, B.; Dirkx, N.; et al. How do online and offline sampling compare in a multinational study of drug use and nightlife behaviour? Int. J. Drug Policy 2020, 82, 102812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resident Advisor. Available online: https://ra.co/ (accessed on 15 November 2022).

- Graham, K.; Bernards, S.; Clapp, J.D.; Dumas, T.M.; Kelley-Baker, T.; Miller, P.G.; Wells, S. Street intercept method: An innovative approach to recruiting young adult high-risk drinkers. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2014, 33, 449–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Goncy, E.A.; Mrug, S. Where and when adolescents use tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana: Comparisons by age, gender, and race. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2013, 74, 288–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pegg, S.; Patterson, I. Rethinking music festivals as a staged event: Gaining insights from understanding visitor motivations and the experiences they seek. J. Conv. Event Tour. 2010, 11, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, F.D.; Engelhardt, L.; Briley, D.A.; Grotzinger, A.D.; Patterson, M.W.; Tackett, J.L.; Strathan, D.B.; Heath, A.; Lynskey, M.; Slutske, W.; et al. Sensation seeking and impulsive traits as personality endophenotypes for antisocial behavior: Evidence from two independent samples. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2017, 105, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terracciano, A.; Esko, T.; Sutin, A.R.; de Moor, M.H.M.; Meirelles, O.; Zhu, G.; Tanaka, T.; Giegling, I.; Nutile, T.; Realo, A.; et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies identifies common variants in CTNNA2 associated with excitement-seeking. Transl. Psychiatry 2017, 1, e49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, K.L.; McCrae, R.R.; Angleitner, A.; Riemann, R.; Livesley, W.J. Heritability of facet-level traits in a cross-cultural twin sample: Support for a hierarchical model of personality. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 74, 1556–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrae, R.R.; Kurtz, J.E.; Yamagata, S.; Terracciano, A. Internal consistency, retest reliability, and their implications for personality scale validity. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 15, 28–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoel, R.D.; De Geus, E.J.; Boomsma, D.I. Genetic analysis of sensation seeking with an extended twin design. Behav. Genet. 2006, 36, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ter Bogt, T.F.M.; Engels, R.C.M.E. “Partying” hard: Party style, motives for and effects of MDMA use at rave parties. Subst. Use Misuse 2005, 40, 1479–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parrott, A.C.; Lock, J.; Conner, A.C.; Kissling, C.; Thome, J. Dance clubbing on MDMA and during abstinence from Ecstasy/MDMA: Prospective neuroendocrine and psychobiological changes. Neuropsychobiology 2008, 57, 165–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, R.H.; Miller, N.S. MDMA (ecstasy) and the rave: A review. Pediatrics 1997, 100, 705–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shafi, A.; Berry, A.J.; Sumnall, H.; Wood, D.M.; Tracy, D.K. New psychoactive substances: A review and updates. Ther. Adv. Psychopharmacol. 2020, 10, 2045125320967197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creagh, S.; Warden, D.; Latif, M.A.; Paydar, A. The new classes of synthetic illicit drugs can significantly harm the brain: A neuro imaging perspective with full review of MRI findings. Clin. Radiol. Imaging J. 2018, 2, 000116. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Stockwell, T.; Macdonald, S. Non–response bias in alcohol and drug population surveys. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2009, 28, 648–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talari, K.; Goyal, M. Retrospective studies—Utility and caveats. J. R. Coll. Physicians Edinb. 2020, 50, 398–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, R.S.; Ames, G.M. Survey confidentiality vs. anonymity: Young men’s self-reported substance use. J. Alcohol Drug Educ. 2002, 47, 32–41. [Google Scholar]

- Richter, L.; Johnson, P.B. Current methods of assessing substance use: A review of strengths, problems, and developments. J. Drug Issues 2001, 31, 809–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decorte, T. Small scale domestic cannabis cultivation: An anonymous web survey among 659 cannabis cultivators in Belgium. Contemp. Drug Probl. 2010, 37, 341–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Więckiewicz, G.; Smardz, J.; Wieczorek, T.; Rymaszewska, J.; Grychowska, N.; Danel, D.; Więckiewicz, M. Patterns of synthetic cathinones use and their impact on depressive symptoms and parafunctional oral behaviors. Psychiatr. Pol. 2021, 55, 1101–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Alcohol | Cannabis | Ecstasy/MDMA/Molly | Cocaine | Ketamine | Amphetamines | Magic Mushrooms | Alkyl Nitrites (Poppers) | Nitrous Oxide | LSD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cannabis | 0.04 | |||||||||

| Ecstasy/MDMA/Molly | 0.14 ** | 0.24 **** | ||||||||

| Cocaine | 0.14 ** | 0.19 *** | 0.47 **** | |||||||

| Ketamine | −0.08 | 0.22 *** | 0.38 **** | 0.24 *** | ||||||

| Amphetamines | −0.03 | 0.09 | 0.30 **** | 0.26 **** | 0.26 *** | |||||

| Magic mushrooms | −0.01 | 0.28 **** | 0.29 **** | 0.16 * | 0.38 **** | 0.08 | ||||

| Alkyl nitrites (poppers) | −0.01 | 0.10 | 0.37 **** | 0.23 ** | 0.18 * | 0.18 * | 0.18 * | |||

| Nitrous oxide | −0.12 | 0.20 ** | 0.27 *** | 0.09 | 0.25 ** | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.28 ** | ||

| LSD | −0.09 | 0.20 ** | 0.19 * | 0.16 * | 0.33 *** | 0.06 | 0.36 **** | 0.04 | 0.12 | |

| Other synthetic hallucinogens | −0.10 | 0.34 **** | 0.31 *** | 0.12 | 0.45 **** | 0.18 | 0.33 *** | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.36 *** |

| Alcohol | Cannabis | Ecstasy/MDMA/Molly | Cocaine | Ketamine | Amphetamines | Magic Mushrooms | Alkyl Nitrites (Poppers) | Nitrous Oxide | LSD | Other Synthetic Hallucinogens | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants (%) who used the substance in the past year | |||||||||||

| 96.43 | 59.03 | 33.01 | 24.01 | 16.21 | 13.46 | 10.63 | 8.62 | 8.25 | 8.18 | 7.14 | |

| Distribution (%) of the location where each substance is most often used | |||||||||||

| Nightclub | 14.38 | 1.43 | 42.73 | 32.29 | 24.54 | 30.90 | 2.10 | 23.28 | 7.21 | 6.54 | 15.79 |

| Licensed festival/outdoor party/rave | 9.11 | 9.08 | 48.64 | 18.50 | 33.80 | 33.15 | 2.80 | 29.31 | 21.62 | 32.71 | 48.42 |

| Unlicensed festival/outdoor party/rave | 0.47 | 0.78 | 3.64 | 1.25 | 8.33 | 7.30 | 2.10 | 3.45 | 10.81 | 8.41 | 5.26 |

| Pub/bar | 47.76 | 2.20 | 0.68 | 7.84 | 2.31 | 1.12 | 1.40 | 2.59 | 2.70 | 0.00 | 2.11 |

| Outside/public space | 2.20 | 15.69 | 0.00 | 0.31 | 2.31 | 1.12 | 23.08 | 2.59 | 9.91 | 17.76 | 4.21 |

| Public events | 73.92 | 29.18 | 95.69 | 60.19 | 71.29 | 73.59 | 31.48 | 61.22 | 52.25 | 65.42 | 75.79 |

| House party | 9.51 | 10.64 | 1.82 | 16.30 | 8.80 | 6.18 | 4.90 | 13.79 | 12.61 | 2.80 | 7.37 |

| Own/friend’s home | 14.53 | 58.24 | 1.82 | 22.26 | 18.06 | 16.85 | 61.54 | 24.14 | 35.14 | 28.97 | 13.68 |

| Private events | 24.04 | 68.88 | 3.64 | 38.56 | 26.86 | 23.03 | 66.44 | 37.93 | 47.75 | 31.77 | 21.05 |

| Other | 2.04 | 1.95 | 0.68 | 1.25 | 1.85 | 3.37 | 2.10 | 0.86 | 0.00 | 2.80 | 3.16 |

| Not Important | Not Very Important | Slightly Important | Very Important (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fun | 0.45 | 0.45 | 10.86 | 88.25 |

| Music | 0.22 | 2.16 | 22.53 | 75.09 |

| Artist | 1.56 | 5.87 | 38.14 | 54.42 |

| Dance | 2.16 | 12.12 | 40.52 | 45.20 |

| Friends | 2.83 | 15.54 | 46.10 | 35.54 |

| Explore | 9.67 | 29.81 | 38.74 | 21.78 |

| Escape | 11.23 | 20.89 | 46.47 | 21.41 |

| Excite | 9.14 | 26.10 | 45.43 | 19.33 |

| Open | 21.41 | 32.42 | 38.88 | 7.29 |

| Meet | 11.97 | 48.33 | 32.49 | 7.21 |

| Alcohol | 20.37 | 39.70 | 34.57 | 5.35 |

| Cope | 53.16 | 32.34 | 10.93 | 3.57 |

| Drugs | 61.71 | 26.25 | 11.15 | 0.89 |

| Partner | 65.80 | 28.25 | 5.50 | 0.45 |

| Sex | 69.22 | 25.72 | 4.76 | 0.30 |

| Fun | Music | Artist | Dance | Friends | Explore | Escape | Excite | Open | Meet | Alc | Cope | Drugs | Partner | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Music | 0.14 **** | |||||||||||||

| Artist | 0.03 | 0.37 **** | ||||||||||||

| Dance | 0.17 **** | 0.16 **** | 0.06 * | |||||||||||

| Friends | 0.10 *** | −0.19 **** | −0.10 *** | 0.04 | ||||||||||

| Explore | 0.12 **** | 0.28 **** | 0.16 **** | 0.16 **** | −0.09 ** | |||||||||

| Escape | 0.12 **** | 0.13 **** | 0.07 ** | 0.03 | −0.02 | 0.21 **** | ||||||||

| Excite | 0.12 **** | 0.16 **** | 0.13 **** | 0.12 **** | 0.01 | 0.39 **** | 0.24 **** | |||||||

| Open | 0.04 | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.24 **** | 0.21 **** | 0.16 **** | 0.19 **** | ||||||

| Meet | 0.06 * | 0.07 * | 0.04 | 0.06 * | 0.08 ** | 0.25 **** | 0.16 **** | 0.23 **** | 0.25 **** | |||||

| Alc | 0.05 | −0.13 **** | −0.07 * | −0.02 | 0.20 **** | −0.02 | 0.16 **** | 0.14 **** | 0.17 **** | 0.09 *** | ||||

| Cope | 0.04 | 0.06 * | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.29 **** | 0.31 **** | 0.23 **** | 0.36 **** | 0.20 **** | 0.15 **** | |||

| Drugs | 0.01 | 0.15 **** | 0.08 ** | 0.21 **** | −0.06 * | 0.24 **** | 0.21 **** | 0.20 **** | 0.02 | 0.07 * | 0.13 **** | 0.15 **** | ||

| Partner | 0.03 | −0.04 | 0.02 | −0.04 | 0.08 ** | 0.11 **** | 0.21 **** | 0.15 **** | 0.20 **** | 0.31 **** | 0.21 **** | 0.19 **** | 0.08 ** | |

| Sex | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.06 * | 0.10 *** | 0.18 **** | 0.21 **** | 0.17 **** | 0.32 **** | 0.27 **** | 0.22 **** | 0.20 **** | 0.61 **** |

| Fun | Music | Artist | Dance | Friends | Explore | Escape | Excite | Open | Meet | Alcohol | Cope | Drugs | Partner | Sex | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol | 0.00 | −0.03 | −0.01 | 0.04 | 0.09 *** | −0.03 | 0.05 | 0.09 ** | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.35 **** | 0.04 | 0.10 *** | 0.03 | 0.13 **** |

| Cannabis | −0.01 | 0.16 **** | 0.09 ** | 0.09 ** | −0.10 ** | 0.23 **** | 0.10 ** | 0.10 ** | −0.01 | 0.07 * | −0.09 ** | 0.10 ** | 0.48 **** | 0.02 | 0.08 ** |

| Ecstasy/MDMA/Molly | 0.11 * | 0.13 ** | −0.02 | 0.24 **** | 0.00 | 0.14 ** | 0.09 * | 0.15 *** | 0.01 | 0.04 | −0.02 | 0.02 | 0.39 **** | 0.01 | 0.07 |

| Cocaine | −0.02 | 0.11 * | 0.04 | 0.06 | −0.01 | 0.11 * | 0.04 | 0.17 *** | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.27 **** | 0.10 * | 0.15 ** |

| Ketamine | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.02 | −0.03 | 0.17 ** | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.07 | −0.15 * | −0.06 | 0.12 * | −0.05 | −0.07 |

| Amphetamines | 0.09 | 0.13 * | 0.16 ** | 0.04 | −0.13 * | 0.22 **** | 0.16 ** | 0.18 ** | 0.02 | 0.09 | −0.04 | 0.05 | 0.24 **** | −0.01 | 0.00 |

| Magic mushrooms | 0.00 | 0.11 | 0.02 | 0.04 | −0.03 | 0.13 * | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.07 | −0.03 | 0.14 * | 0.24 **** | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Alkyl nitrites (poppers) | 0.06 | 0.02 | −0.03 | 0.14 * | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.17 * | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.12 | −0.02 | 0.21 ** |

| Nitrous oxide | −0.03 | 0.08 | −0.03 | 0.03 | −0.05 | 0.12 | 0.01 | 0.09 | −0.02 | 0.12 | −0.10 | 0.04 | 0.09 | −0.16 * | −0.06 |

| LSD | 0.14 | 0.01 | −0.09 | 0.10 | −0.07 | 0.19 ** | −0.06 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.08 | −0.15 * | 0.01 | 0.16 * | −0.01 | −0.04 |

| Other synthetic hallucinogens | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.04 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.07 | 0.13 | −0.04 | 0.05 | 0.28 ** | 0.20 * | 0.18 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Van Dyck, E.; Ponnet, K.; Van Havere, T.; Hauspie, B.; Dirkx, N.; Schrooten, J.; Waldron, J.; Grabski, M.; Freeman, T.P.; Curran, H.V.; et al. Substance Use and Attendance Motives of Electronic Dance Music (EDM) Event Attendees: A Survey Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1821. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20031821

Van Dyck E, Ponnet K, Van Havere T, Hauspie B, Dirkx N, Schrooten J, Waldron J, Grabski M, Freeman TP, Curran HV, et al. Substance Use and Attendance Motives of Electronic Dance Music (EDM) Event Attendees: A Survey Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(3):1821. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20031821

Chicago/Turabian StyleVan Dyck, Edith, Koen Ponnet, Tina Van Havere, Bert Hauspie, Nicky Dirkx, Jochen Schrooten, Jon Waldron, Meryem Grabski, Tom P. Freeman, Helen Valerie Curran, and et al. 2023. "Substance Use and Attendance Motives of Electronic Dance Music (EDM) Event Attendees: A Survey Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 3: 1821. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20031821

APA StyleVan Dyck, E., Ponnet, K., Van Havere, T., Hauspie, B., Dirkx, N., Schrooten, J., Waldron, J., Grabski, M., Freeman, T. P., Curran, H. V., & De Neve, J. (2023). Substance Use and Attendance Motives of Electronic Dance Music (EDM) Event Attendees: A Survey Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(3), 1821. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20031821