Optimization of the Convective Dose in On-Line Hemodiafiltration: Prospective Interventional Cohort Study—Conducted at Soissons Hospital, France

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Nature, Setting and Period of the Study

2.2. Study Population and Patient Selection

2.3. Dialysis Equipment

2.4. Study Parameters of Interest

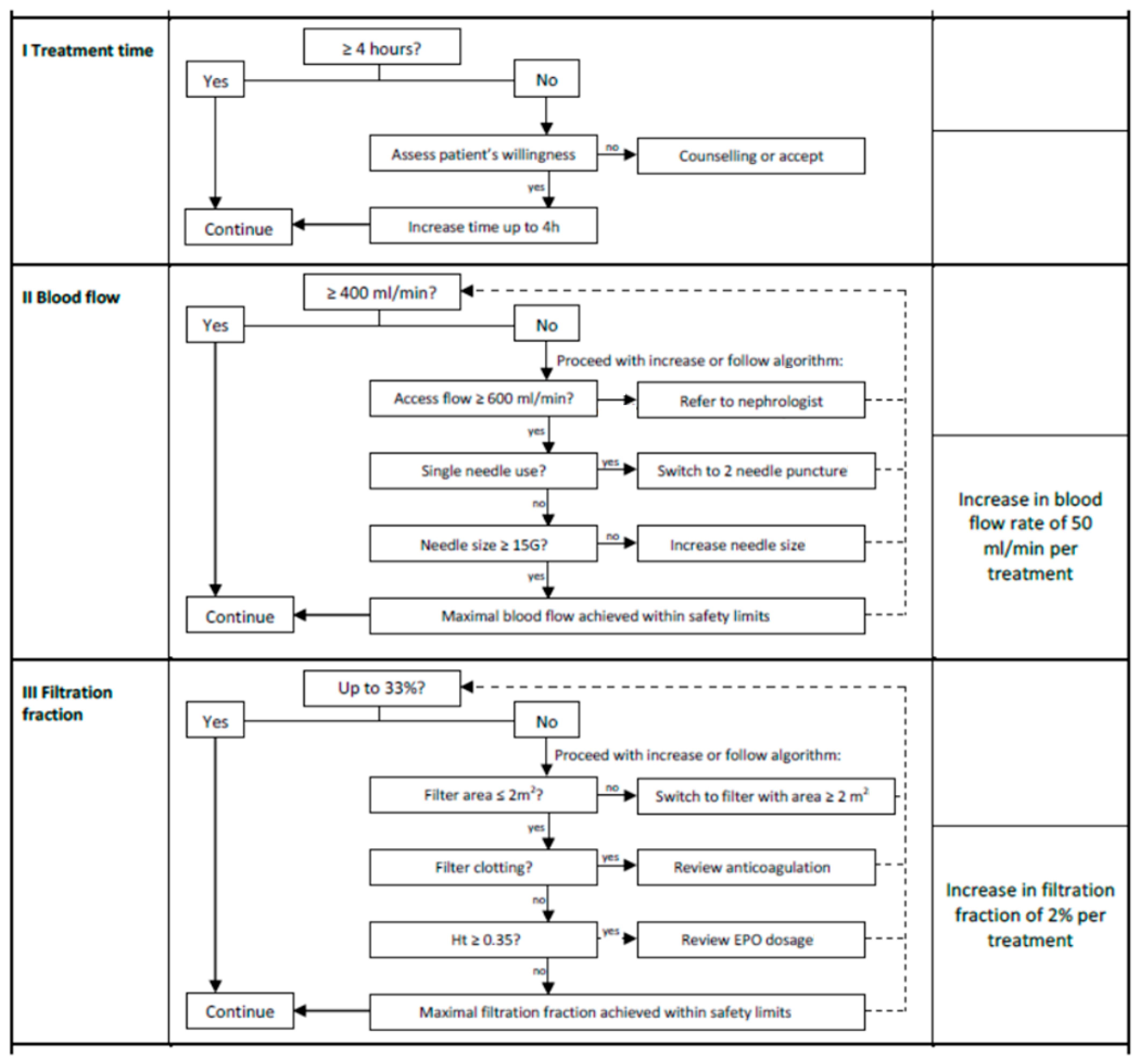

2.5. Intervention

2.6. Statistical Analysis

2.7. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics of the Study Population

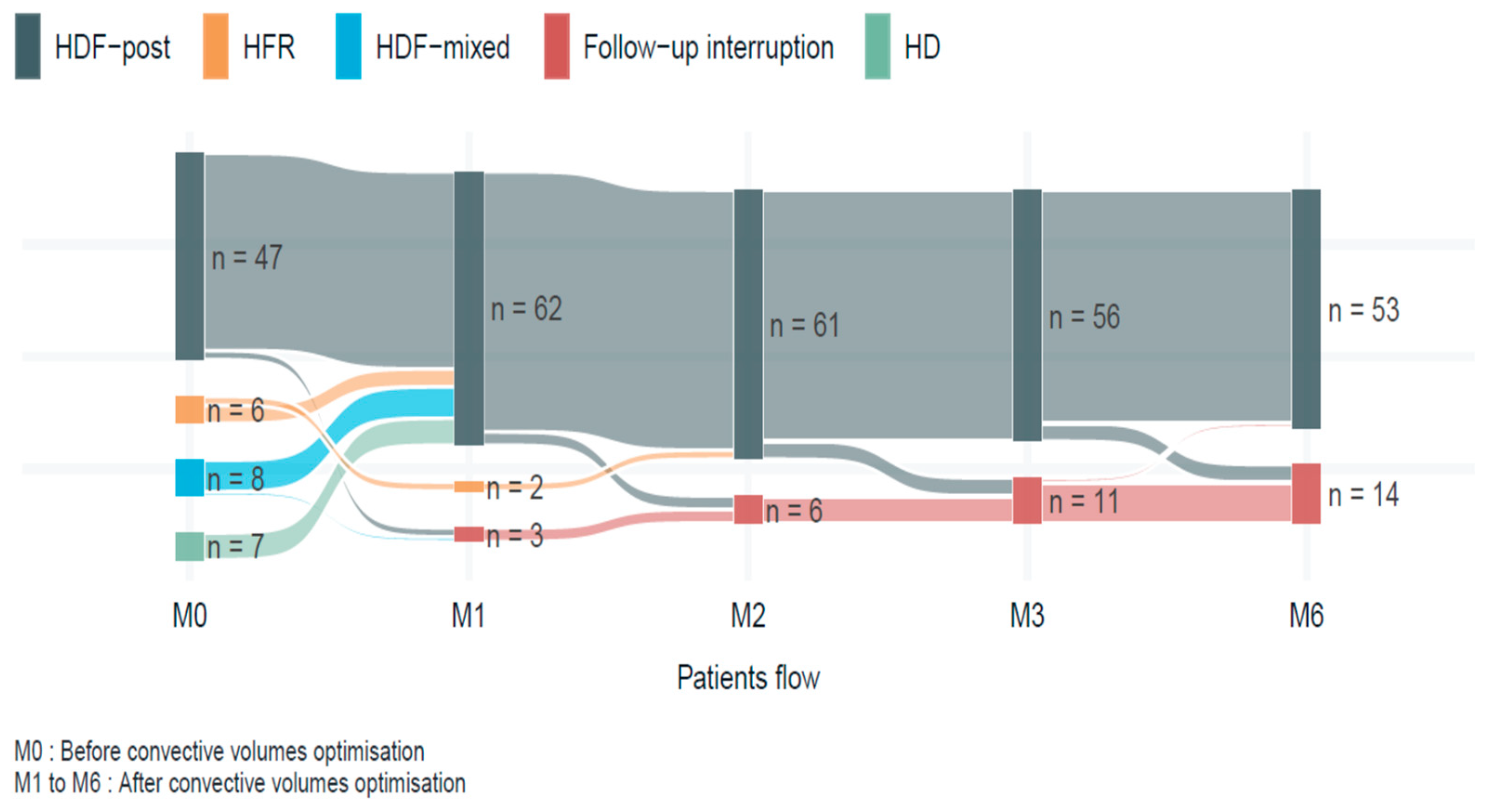

3.2. Evolution of OL-HDF Sessions After Optimization Protocol

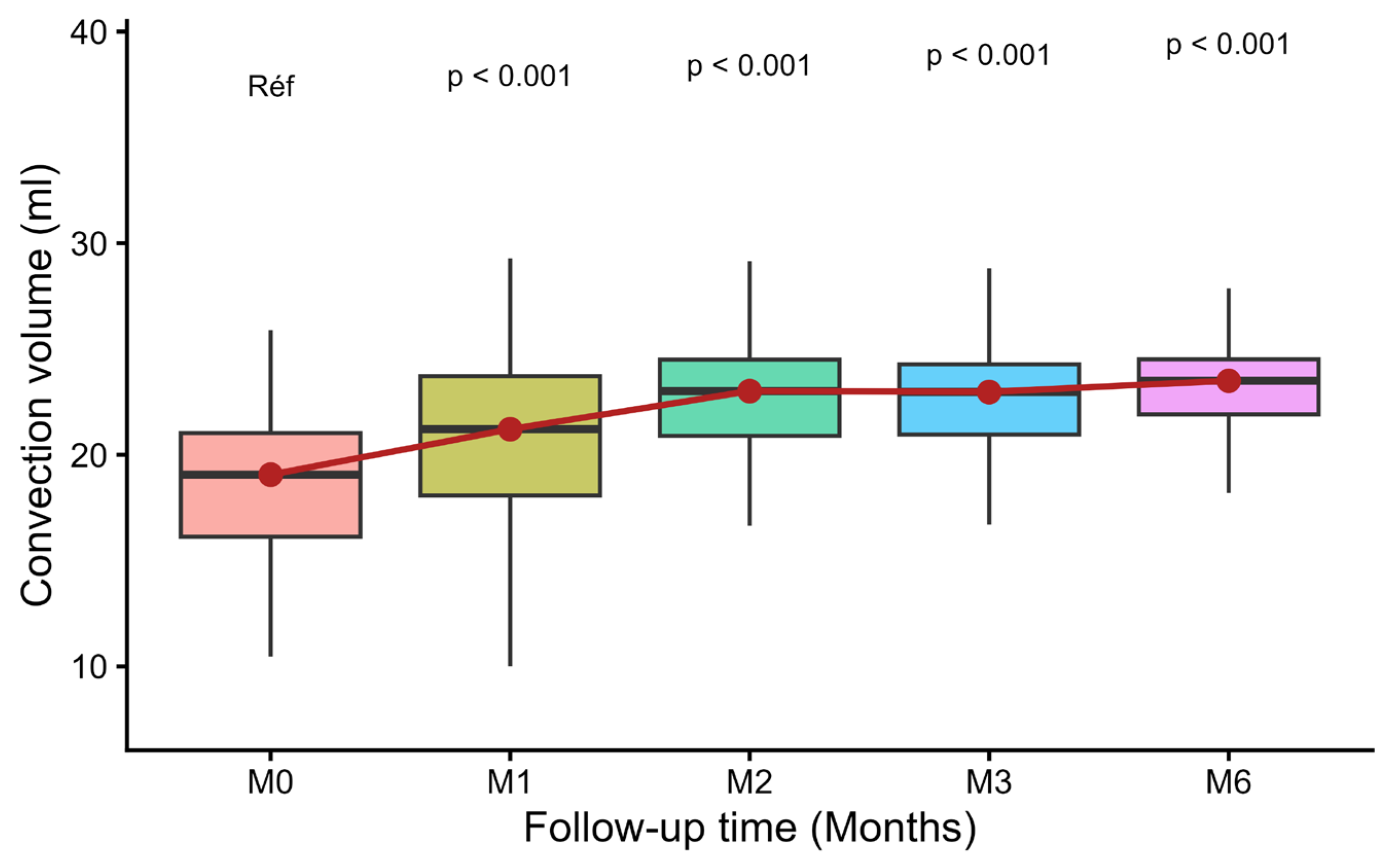

3.3. Evolution of Convective Volume

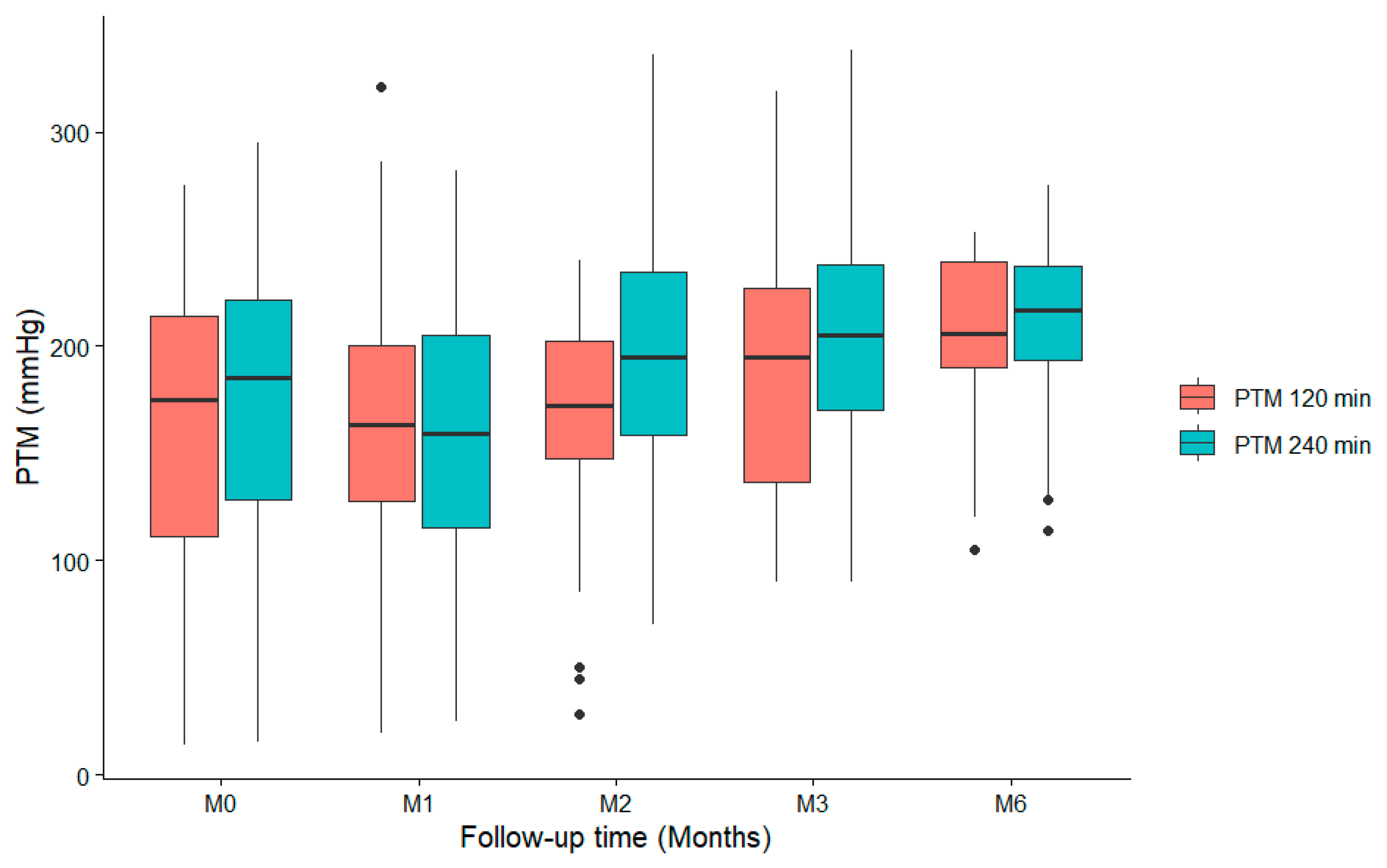

3.4. Evolution of TMP

3.5. Patient Characteristics by Convective Volume

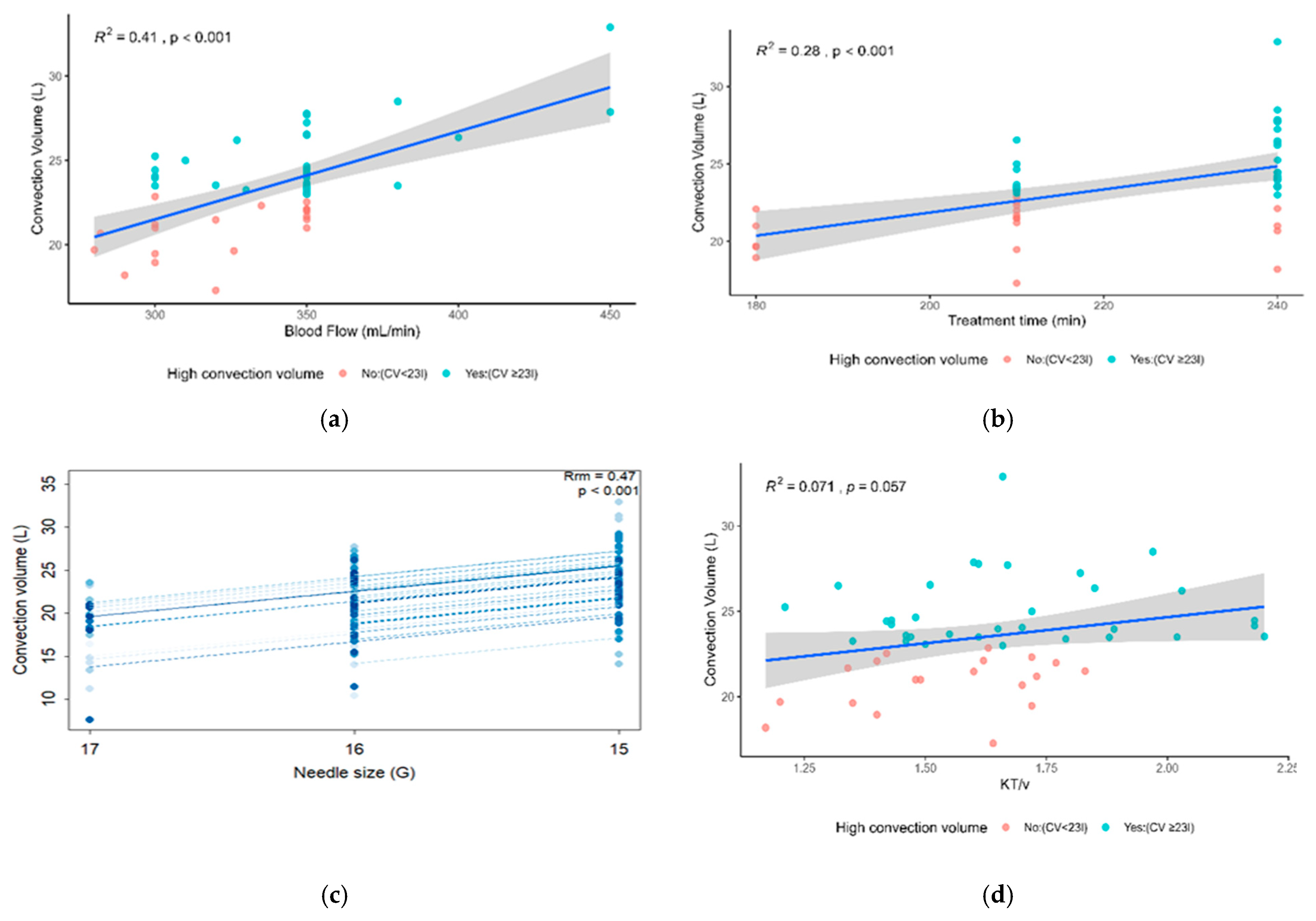

3.6. Factors Associated with Reaching High Convective Volume (M6)

4. Discussion

4.1. General Characteristics of the Population

4.2. Changes in Dialysis Parameters After Optimization

- The prevalence of hemodynamic fragility in the populations studied, particularly in elderly subjects;

- The variability of practices between centers, in particular the size of needles used, vascular puncture protocols and clinical tolerance thresholds;

- Vascular access (AVF vs. catheter), which may limit flow rates in certain populations.

4.3. Evolution of Convective Volume and Factors Associated with Achieving High Convective Volume

4.4. Purification of β2-Microglobulin

4.5. Strengths, Limitations and Outlook

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- GBD Chronic Kidney Disease Collaboration. Global, regional, and national burden of chronic kidney disease, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2020, 395, 709–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kazes, I.; Solignac, J.; Lassalle, M.; Mercadal, L.; Couchoud, C.; on behalf of the REIN Registry. Twenty years of the French Renal Epidemiology and Information Network. Clin. Kidney J. 2024, 17, sfad240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couchoud, C.; Raffray, M.; Lassalle, M.; Duisenbekov, Z.; Moranne, O.; Erbault, M.; Lazareth, H.; Parmentier, C.; Guebre-Egziabher, F.; Hamroun, A.; et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in France: Methodological considerations and pitfalls with the use of Health claims databases. Clin. Kidney J. 2024, 17, sfae117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huijben, J.A.; Kramer, A.; Kerschbaum, J.; de Meester, J.; Collart, F.; Arévalo, O.L.R.; Helve, J.; Lassalle, M.; Palsson, R.; Dam, M.T.; et al. Increasing numbers and improved overall survival of patients on kidney replacement therapy over the last decade in Europe: An ERA Registry study. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2023, 38, 1027–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liyanage, T.; Toyama, T.; Hockham, C.; Ninomiya, T.; Perkovic, V.; Woodward, M.; Fukagawa, M.; Matsushita, K.; Praditpornsilpa, K.; Hooi, L.S.; et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in Asia: A systematic review and analysis. BMJ Glob. Health 2022, 7, e007525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumaili, E.K. Kidney health for all in sub-Saharan Africa: Challenges and prospects. Ann. Afr. Med. 2022, 16, e5018–e5024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaze, A.D.; Ilori, T.; Jaar, B.G.; Echouffo-Tcheugui, J.B. Burden of chronic kidney disease on the African continent: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Nephrol. 2018, 19, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Diallo, A.; Niamkey, E.; Beda, Y. Chronic renal failure in Côte d’Ivoire: A study of 800 hospitalised cases. Bull. Soc. Pathol. Exot. 1997, 90, 346–348. [Google Scholar]

- Ene-Iordache, B.; Perico, N.; Bikbov, B.; Carminati, S.; Remuzzi, A.; Perna, A.; Islam, N.; Bravo, R.F.; Aleckovic-Halilovic, M.; Zou, H.; et al. Chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular risk in six regions of the world (ISN-KDDC): A cross-sectional study. Lancet Glob. Health 2016, 4, e307–e319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanifer, J.W.; Jing, B.; Tolan, S.; Helmke, N.; Mukerjee, R.; Naicker, S.; Patel, U. The epidemiology of chronic kidney disease in sub-Saharan Africa: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2014, 2, e174–e181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sumaili, E.K.; Krzesinski, J.M.; Cohen, E.P.; Nseka, N.M. Epidemiology of chronic kidney disease in the Democratic Republic of Congo: A review of cross-sectional studies from Kinshasa, the capital. Nephrol. Ther. 2010, 6, 232–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, S.A.; Bots, M.L.; Canaud, B.; Davenport, A.; Grooteman, M.P.; Kircelli, F.; Locatelli, F.; Maduell, F.; Morena, M.; Nubé, M.J.; et al. Haemodiafiltration and mortality in patients with end-stage renal disease: Analysis of pooled individual data from four randomised controlled trials. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2016, 31, 978–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eknoyan, G.; Beck, G.J.; Cheung, A.K.; Daugirdas, J.T.; Greene, T.; Kusek, J.W.; Allon, M.; Bailey, J.; Delmez, J.A.; Depner, T.A.; et al. Effect of dialysis dose and membrane flux in maintenance hemodialysis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 347, 2010–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locatelli, F.; Martin-Malo, A.; Hannedouche, T.; Loureiro, A.; Papadimitriou, M.; Wizemann, V.; Jacobson, S.H.; Czekalski, S.; Ronco, C.; Vanholder, R.; et al. Effect of membrane permeability on survival in hemodialysis patients. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2009, 20, 645–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ledebo, I.; Blankestijn, P.J. Hemodiafiltration-optimal efficacy and safety. NDT Plus 2010, 3, 8–16. [Google Scholar]

- Grooteman, M.P.; van den Dorpel, M.A.; Bots, M.L.; Penne, E.L.; van der Weerd, N.C.; Mazairac, A.H.; den Hoedt, C.H.; van der Tweel, I.; Lévesque, R.; Nubé, M.J.; et al. Effect of online hemodiafiltration on all-cause mortality and cardiovascular outcomes. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2012, 23, 1087–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Blankestijn, P.J.; Vernooij, R.W.M.; Hockham, C.; Strippoli, G.F.M.; Canaud, B.; Hegbrant, J.; Barth, C.; Covic, A.; Cromm, K.; Cucui, A.; et al. Effect of Hemodiafiltration or Hemodialysis on Mortality in Kidney Failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 700–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, A.; Park, H.C.; Kim, D.H.; Choi, H.B.; Song, G.H.; Kim, H.; Kim, S.H.; Choi, G.; Kim, J.K.; Song, Y.R.; et al. Impact of needle type on substitution volume during online hemodiafiltration: Plastic cannulae versus metal needles. Kidney Res. Clin. Pract. 2023, 42, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Carrera, F.; Jacobson, S.H.; Costa, J.; Marques, M.; Ferrer, F. Better Anti-Spike IgG Antibody Response to SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine in Patients on Haemodiafiltration than on Haemodialysis. Blood Purif. 2023, 52, 600–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maduell, F.; Moreso, F.; Pons, M.; Ramos, R.; Mora-Macià, J.; Carreras, J.; Soler, J.; Torres, F.; Campistol, J.M.; Martinez-Castelao, A.; et al. High-efficiency postdilution online hemodiafiltration reduces all-cause mortality in hemodialysis patients. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2013, 24, 487–497, Erratum in J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2014, 25, 1130. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2012080875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Morena, M.; Jaussent, A.; Chalabi, L.; Leray-Moragues, H.; Chenine, L.; Debure, A.; Thibaudin, D.; Azzouz, L.; Patrier, L.; Maurice, F.; et al. Treatment tolerance and patient-reported outcomes favor online hemodiafiltration compared to high-flux hemodialysis in the elderly. Kidney Int. 2017, 91, 1495–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ok, E.; Asci, G.; Toz, H.; Ok, E.S.; Kircelli, F.; Yilmaz, M.; Hur, E.; Demirci, M.S.; Demirci, C.; Duman, S.; et al. Mortality and cardiovascular events in online haemodiafiltration (OL-HDF) compared with high-flux dialysis: Results from the Turkish OL-HDF Study. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2013, 28, 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Roij van Zuijdewijn, C.L.M.; Chapdelaine, I.; Nubé, M.J.; Blankestijn, P.J.; Bots, M.L.; Konings, C.J.A.M.; Kremer Hovinga, T.K.; Molenaar, F.M.; van der Weerd, N.C.; Grooteman, M.P.C. Achieving high convection volumes in postdilution online hemodiafiltration: A prospective multicenter study. Clin. Kidney J. 2017, 10, 804–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chapdelaine, I.; Mostovaya, I.M.; Blankestijn, P.J.; Bots, M.L.; van den Dorpel, M.A.; Lévesque, R.; Nubé, M.J.; ter Wee, P.M.; Grooteman, M.P.; CONTRAST Investigators. Treatment policy rather than patient characteristics determines convection volume in online post-dilution hemodiafiltration. Blood Purif. 2014, 37, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penne, E.L.; van der Weerd, N.C.; Bots, M.L.; van den Dorpel, M.A.; Grooteman, M.P.; Lévesque, R.; Nubé, M.J.; Ter Wee, P.M.; Blankestijn, P.J.; CONTRAST Investigators. Patient- and treatment-related determinants of convective volume in post-dilution haemodiafiltration in clinical practice. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2009, 24, 3493–3499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcelli, D.; Kopperschmidt, P.; Bayh, I.; Jirka, T.; Merello, J.I.; Ponce, P.; Ladanyi, E.; Di Benedetto, A.; Dovc-Dimec, R.; Rosenberger, J.; et al. Modifiable factors associated with achievement of high-volume post-dilution hemodiafiltration: Results from an international study. Int. J. Artif. Organs 2015, 38, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables n = 67 | |

|---|---|

| Demographic * | |

| Average age (Years) | 68.75 ± 14.85 |

| Men (n, %) | 38 (56.72%) |

| Weight (kg) | 75.22 ± 16.93 |

| Height (cm) | 167.45 ± 10.27 |

| BMI | 26.7 ± 4.7 |

| Clinical data | |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 39 (59.09%) |

| Coronary artery disease, n (%) | 13 (19.70%) |

| High blood pressure, n (%) | 59 (89.39%) |

| ACFA | 16 (24.2%) |

| Dyslipidemia | 48 (71.60%) |

| Alcohol | 25 (37.30%) |

| Tobacco | 35 (52.20%) |

| Previous kidney transplant | 6 (9.10%) |

| Nephropathy | |

| Glomerular nephropathy | 11 (16.67%) |

| Vascular | 35 (53.03%) |

| Diabetic | 26 (39.39%) |

| Polycystic kidney disease | 2 (3.03%) |

| CTIN | 8 (12.10%) |

| Undetermined | 5 (27.8) |

| Length of time on dialysis (months) | 60 ± 81 |

| History of renal transplantation | 6 (9.09%) |

| Residual urine output | |

| <500 (mL/d) | 30 (44.80%) |

| Laboratory data | |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 35.7 ± 4.3 |

| Hematocrit | 34.9 ± 3.7 |

| Hematocrit > 0.35 (>35%) | 34 (51.52%) |

| Phosphate (mmol/L) | 1.6 (0.7–3) |

| Calcium (mmol/L) | 2.3 (2.2–2.4) |

| NT-proBNP ¥ | 10,802 (2763–11,644) |

| Treatment characteristics (dialysis) | |

| Session duration (min) ¥ | 219 (270–240) |

| Blood flow (mL/min) ¥ | 286 (270–295) |

| Vascular access | |

| Central venous catheter | 18 (26.9%) |

| AVF | 49 (73.1%) |

| AVF flow mL/min | 1000 (825–1275) |

| spKt/Vurea | 1.2 (1.1–1.3) |

| Net UF (mL) | 1761.1 (1075–2215) |

| Characteristics | M0 | M1 | p | M2 | p | M3 | p | M6 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 67 | 62 | 61 | 56 | 53 | ||||

| Number of patients in OL-HDF | 47 | 62 | 61 | 56 | 53 | ||||

| Total antico./session (IU) | 4484 ± 1860 | 4644 ± 1789 | 4535 ± 1868 | 4509 ± 1793 | 4592 ± 1914 | ||||

| Actual blood flow (mL/min) § | 284.6 ± 29.8 | 320.3 ± 36.6 | <0.001 | 332.6 ± 38.7 | <0.001 | 332.8 ± 35.7 | <0.001 | 338.5 ± 34.7 | <0.001 |

| Effective session time (min) § | 218.9 ± 23.9 | 224.6 ± 32.7 | 0.34 | 222.5 ± 21.6 | 0.34 | 222.7 ± 21.1 | 0.32 | 222.1 ± 19.9 | 0.46 |

| Convective volume (CV) | 18.5 ± 3.8 | 21.0 ± 4.2 | <0.001 | 22.7 ± 3.1 | <0.001 | 22.7 ± 3.0 | <0.001 | 23.5 ± 2.8 | <0.001 |

| of which patients with CV > 23 L, n(%) | 8 (17%) | 17 (27%) | 0.02 | 31 (50%) | <0.001 | 27 (48.2%) | <0.001 | 33 (62.3%) | <0.001 |

| Substitution volume (L) § | 16.7 ± 3.7 | 19.1 ± 3.9 | <0.001 | 20.7 ± 3.0 | <0.001 | 20.7 ± 3.1 | <0.001 | 21.0 ± 2.8 | <0.001 |

| Net patient ultrafiltration (mL) § | 1777.1 ± 932.5 | 1927.9 ± 956.2 | 0.29 | 2007.5 ± 986.4 | 0.16 | 2017.5 ± 1055.2 | 0.18 | 2487.7 ± 782.8 | <0.001 |

| Filtration fraction (Q Conv/QB) § | 29.8 ± 5.0 | 29.6 ± 5.6 | 0.27 | 30.8 ± 3.1 | 0.43 | 30.9 ± 3.5 | 0.49 | 31.5 ± 2.8 | 0.13 |

| spKt/V § | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 0.017 | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 0.035 | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 0.01 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 0.01 |

| Beta2 microglobulin (ng/mL) § | 27.2 ± 88 | 29.3 ± 9.4 | 0.21 | - | - | 29.5 ± 10.7 | 0.28 | 25.4 ± 8.7 | 0.21 |

| % patients with 15G needle | 2 (8.2%) | 30 (65.2%) | 0.01 | 26 (59.1%) | 0.03 | 20 (48.8%) | 0.03 | 15 (39.5%) | 0.03 |

| Dialyzer Adsorbents * (n, %) * | 15 (10.7) | 6 (4.4) | 0.01 | 4 (3.0) | 0.001 | 3 (2.5) | 0.002 | 3 (2.7) | <0.001 |

| Membrane surface area (m2) * | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | <0.001 | 2.04 ± 0.1 | <0.001 | 2.1 ± 0.1 | <0.001 | 2.1 ± 0.1 | <0.001 |

| of which n % surfaces ≥ 2 m2 | 21 (31.3%) | 29 (46.0%) | 0.06 | 29 (48.3%) | 0.06 | 25 (43.9%) | 0.29 | 27 (51.9%) | 0.15 |

| Characteristics * | CV ≥ 23 L N = 33 | CV < 23 L N = 19 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 69 (13) | 72 (16) | 0.5 |

| Sex: M | 19 (57.58%) | 10 (52.63%) | 0.7 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.3 (4.4) | 24.7 (3.2) | 0.028 |

| BMI > 30 (kg/m2) | 21 (63.64%) | 7 (36.84%) | 0.06 |

| Diabetes | 22 (66.67%) | 11 (57.89%) | 0.5 |

| Coronary artery disease | 6 (18.18%) | 4 (21.05%) | >0.9 |

| HTA | 32 (96.97%) | 15 (78.95%) | 0.054 |

| ACFA | 10 (30.30%) | 5 (26.32%) | 0.8 |

| Dyslipidemia | 24 (72.73%) | 11 (57.89%) | 0.3 |

| Alcohol | 8 (24.24%) | 7 (36.84%) | 0.3 |

| Tobacco | 17 (51.52%) | 8 (42.11%) | 0.5 |

| atcd_transpl_renal | 3 (9.09%) | 2 (10.53%) | >0.9 |

| nephro_glomerular | 4 (12.12%) | 4 (21.05%) | 0.4 |

| nephro_vascular | 18 (54.55%) | 10 (52.63%) | 0.9 |

| nephro_diabetic | 14 (42.42%) | 9 (47.37%) | 0.7 |

| CTIN | 7 (21.21%) | 1 (5.26%) | 0.2 |

| old_dialysis_(months) | 51 (64) | 82 (120) | 0.2 |

| Race: Caucasian | 32 (96.97%) | 19 (100.00%) | >0.9 |

| Black | 1 (3.03%) | 0 (0.00%) | |

| Oral anticoagulants | 8 (24.24%) | 7 (36.84%) | 0.3 |

| Residual urine output > 0.5 (L) | 16 (53.33%) | 8 (50.00%) | 0.8 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 137(21) | 141(18) | 0.47 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 35.7 (4.4) | 34.4 (4.0) | 0.2 |

| Hcte > 0.35 | 20 (60.61%) | 10 (52.63%) | 0.6 |

| Phosphate (mmol/L) | 1.60 (0.50) | 1.33 (0.40) | 0.067 |

| Ca++ (mmol/L) | 2.27 (0.17) | 2.22 (0.16) | 0.2 |

| Ntprobnp (ng/mL) | 10,403 (13,134) | 13,954 (14,579) | 0.4 |

| Session time (min) | 228 (19) | 204 (23) | <0.001 |

| Blood flow (mL/min) | 299 (38) | 278 (24) | 0.049 |

| Vascular access | |||

| Tunnelled central venous catheter | 7 (21.21%) | 7 (36.84%) | 0.33 |

| AVF | 26 (78.79%) | 12 (63.16%) | 0.2 |

| Kt/V | 1.28 (0.22) | 1.21 (0.21) | >0.9 |

| Net ultrafiltration (mL) | 1850 (931) | 1625 (656) | 0.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lukoki-Beudin, B.; Kakomkate, T.; Ibeghouchene, W.; Carreira, C.; Ouertani, I.; Wembulua, B.S.; Nlandu, Y.M.; Engole, Y.M.; Ingole, M.-F.M.; Longo, A.L.; et al. Optimization of the Convective Dose in On-Line Hemodiafiltration: Prospective Interventional Cohort Study—Conducted at Soissons Hospital, France. Diseases 2026, 14, 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases14010020

Lukoki-Beudin B, Kakomkate T, Ibeghouchene W, Carreira C, Ouertani I, Wembulua BS, Nlandu YM, Engole YM, Ingole M-FM, Longo AL, et al. Optimization of the Convective Dose in On-Line Hemodiafiltration: Prospective Interventional Cohort Study—Conducted at Soissons Hospital, France. Diseases. 2026; 14(1):20. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases14010020

Chicago/Turabian StyleLukoki-Beudin, Bedel, Tchilabalo Kakomkate, Wahiba Ibeghouchene, Céline Carreira, Imene Ouertani, Bruce Shinga Wembulua, Yannick Mayamba Nlandu, Yannick Mompango Engole, Marie-France Mboliasa Ingole, Augustin Luzayadio Longo, and et al. 2026. "Optimization of the Convective Dose in On-Line Hemodiafiltration: Prospective Interventional Cohort Study—Conducted at Soissons Hospital, France" Diseases 14, no. 1: 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases14010020

APA StyleLukoki-Beudin, B., Kakomkate, T., Ibeghouchene, W., Carreira, C., Ouertani, I., Wembulua, B. S., Nlandu, Y. M., Engole, Y. M., Ingole, M.-F. M., Longo, A. L., Kajingulu, F. M., Makulo, J. R. R., Nsumbu, J. B., Mokoli, V. M., Nseka, N. M., Sumaili, E. K., Bukasa-Kakamba, J., Tran, H. H.-V., Thu, A., ... Bukabau, J. B. (2026). Optimization of the Convective Dose in On-Line Hemodiafiltration: Prospective Interventional Cohort Study—Conducted at Soissons Hospital, France. Diseases, 14(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases14010020