The Impact of Proactive Fecal Calprotectin Collection in an Outreach Protocol for Biologic-Naïve Ulcerative Colitis Patients–Ulcerative Colitis Clinical Outreach (UCCO)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Patients

2.3. Protocol

2.4. Outcomes

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Patient Characteristics

3.2. Medication Adherence

3.3. Disease Activity

3.3.1. Clinical Indices

3.3.2. Hematological and Biochemical Parameters

3.3.3. FCP

3.4. Physician Surveys

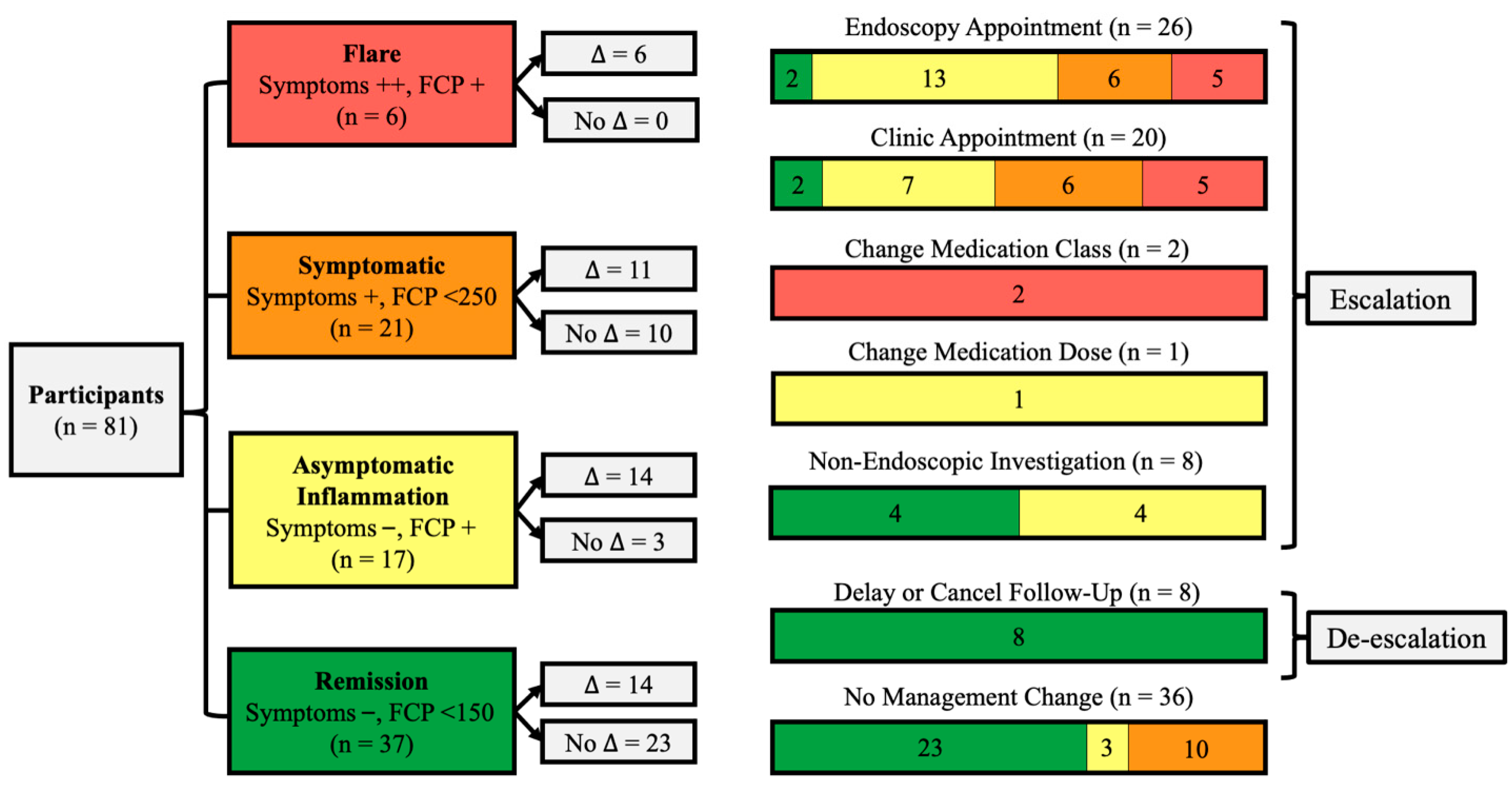

Management Changes

3.5. Endoscopy

3.6. Regression

3.7. Clinically Relevant Subgroups

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| FCP | Fecal calprotectin |

| IBD | Inflammatory Bowel Disease |

| mHealth | Mobile health |

| UC | Ulcerative Colitis |

References

- Gajendran, M.; Loganathan, P.; Jimenez, G.; Catinella, A.P.; Ng, N.; Umapathy, C.; Ziade, N.; Hashash, J.G. A comprehensive review and update on ulcerative colitis. Dis. Mon. 2019, 65, 100851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.; Ha, C. Epidemiology and pathogenesis of ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterol. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 49, 643–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windsor, J.W.; Kuenzig, M.E.; Murthy, S.K.; Bitton, A.; Bernstein, C.N.; Jones, J.L.; Lee, K.; Targownik, L.E.; Peña-Sánchez, J.N.; Rohatinsky, N.; et al. The 2023 Impact of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Canada: Executive Summary. J. Can. Assoc. Gastroenterol. 2023, 6, S1–S8. [Google Scholar]

- Solitano, V.; D’Amico, F.; Fiorino, G.; Paridaens, K.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Danese, S. Key strategies to optimize outcomes in mild-to-moderate ulcerative colitis. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, E.; Paridaens, K.; Al Awadhi, S.; Begun, J.; Cheon, J.H.; Dignass, A.U.; Magro, F.; Márquez, J.R.; Moschen, A.R.; Narula, N.; et al. Modelling the benefits of an optimised treatment strategy for 5-ASA in mild-to-moderate ulcerative colitis. BMJ Open Gastro. 2022, 9, e000853. [Google Scholar]

- Kane, S.; Huo, D.; Aikens, J.; Hanauer, S. Medication nonadherence and the outcomes of patients with quiescent ulcerative colitis. Am. J. Med. 2003, 114, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, S.; Ingle, S.B.; Dhillon, S.; Yadav, S.; Harmsen, W.S.; Zinsmeister, A.R.; Tremaine, W.J.; Sandborn, W.J.; Loftus, E.V., Jr. Cumulative incidence and risk factors for hospitalization and surgery in a population-based cohort of ulcerative colitis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2013, 19, 1858–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, C.; Lu, Y.; Shen, H.; Zhu, L. Monitoring of intestinal inflammation and prediction of recurrence in ulcerative colitis. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 57, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, L.R.; Martin, F.; Greer, S.; Robinson, M.; Greenberger, N.; Saibil, F.; Martin, T.; Sparr, J.; Prokipchuk, E.; Borgen, L. 5-Aminosalicylic acid enema in the treatment of distal ulcerative colitis, proctosigmoiditis, and proctitis. Gastroenterology 1987, 92, 1894–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.D.; Chuai, S.; Nessel, L.; Lichtenstein, G.R.; Aberra, F.N.; Ellenberg, J.H. Use of the noninvasive components of the Mayo score to assess clinical response in ulcerative colitis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2008, 14, 1660–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cross, R.K.; Langenberg, P.; Regueiro, M.; Schwartz, D.A.; Tracy, J.K.; Collins, J.F.; Katz, J.; Ghazi, L.; Patil, S.A.; Quezada, S.M.; et al. A randomized controlled trial of TELEmedicine for patients with inflammatory bowel disease (TELE-IBD). Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 114, 472–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, M.J.; Boonen, A.; van der Meulen-de, A.E.; Romberg-Camps, M.J.; van Bodegraven, A.A.; Mahmmod, N.; Markus, T.; Dijkstra, G.; Winkens, B.; van Tubergen, A.; et al. Cost-effectiveness of telemedicine-directed specialized vs standard care for patients with inflammatory bowel diseases in a randomized trial. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 18, 1744–1752. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Del Hoyo, J.; Nos, P.; Bastida, G.; Faubel, R.; Muñoz, D.; Garrido-Marín, A.; Valero-Pérez, E.; Bejar-Serrano, S.; Aguas, M. Telemonitoring of Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis (TECCU): Cost-effectiveness analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e15505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCombie, A.; Walmsley, R.; Barclay, M.; Ho, C.; Langlotz, T.; Regenbrecht, H.; Gray, A.; Visesio, N.; Inns, S.; Schultz, M. A noninferiority randomized clinical trial of the use of the smartphone-based health applications IBDsmart and IBDoc in the care of inflammatory bowel disease patients. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2020, 26, 1098–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Hoyo, J.; Millán, M.; Garrido-Marín, A.; Aguas, M. Are we ready for telemonitoring inflammatory bowel disease? A review of advances, enablers, and barriers. World J. Gastroenterol. 2023, 29, 1139–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, D.; Ricciuto, A.; Lewis, A.; D’amico, F.; Dhaliwal, J.; Griffiths, A.M.; Bettenworth, D.; Sandborn, W.J.; Sands, B.E.; Reinisch, W.; et al. STRIDE-II: An update on the Selecting Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (STRIDE) Initiative of the International Organization for the Study of IBD (IOIBD): Determining therapeutic goals for treat-to-target strategies in IBD. Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 1570–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortesi, P.A.; Fiorino, G.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Mantovani, L.G.; Jairath, V.; Paridaens, K.; Andersson, F.L.; Danese, S. Non-invasive monitoring and treat-to-target approach are cost-effective in patients with mild–moderate ulcerative colitis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2023, 57, 486–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, K.W.; Tremaine, W.J.; Ilstrup, D.M. Coated oral 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy for mildly to moderately active ulcerative colitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 1987, 317, 1625–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.H.Y.; Horne, R.; Hankins, M.; Chisari, C. The Medication Adherence Report Scale: A measurement tool for eliciting patients’ reports of nonadherence. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2020, 86, 1281–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ediger, J.P.; Walker, J.R.; Graff, L.; Lix, L.; Clara, I.; Rawsthorne, P.; Rogala, L.; Miller, N.; McPhail, C.; Deering, K.; et al. Predictors of medication adherence in inflammatory bowel disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2007, 102, 1417–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gisbert, J.P.; Bermejo, F.; Pérez-Calle, J.L.; Taxonera, C.; Vera, I.; McNicholl, A.G.; Algaba, A.; López, P.; López-Palacios, N.; Calvo, M.; et al. Fecal calprotectin and lactoferrin for the prediction of inflammatory bowel disease relapse. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2009, 15, 1190–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hart, L.; Chavannes, M.; Kherad, O.; Maedler, C.; Mourad, N.; Marcus, V.; Afif, W.; Bitton, A.; Lakatos, P.L.; Brassard, P.; et al. Faecal calprotectin predicts endoscopic and histological activity in clinically quiescent ulcerative colitis. J. Crohns Colitis 2020, 14, 46–52. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Zhao, X.; Li, X.; Lu, M.; Zhang, H. Systematic review with meta-analysis: Fecal calprotectin as a surrogate marker for predicting relapse in adults with ulcerative colitis. Mediat. Inflamm. 2019, 2019, 2136501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.; Panchal, H.; Dubinsky, M.C. Fecal calprotectin levels predict histological healing in ulcerative colitis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2017, 23, 1600–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Reis Malvão, L.; Madi, K.; Esberard, B.C.; de Amorim, R.F.; dos Santos Silva, K.; e Silva, K.F.; de Souza, H.S.P.; Carvalho, A.T.P. Fecal calprotectin as a noninvasive test to predict deep remission in patients with ulcerative colitis. Medicine 2021, 100, e24058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashorov, O.; Hamouda, D.; Dickman, R.; Perets, T.T. Clinical accuracy of a new rapid assay for fecal calprotectin measurement. Clin. Lab. 2020, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elkjaer, M.; Burisch, J.; Voxen Hansen, V.; Deibjerg Kristensen, B.; Slott Jensen, J.K.; Munkholm, P. A new rapid home test for faecal calprotectin in ulcerative colitis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2010, 31, 323–330. [Google Scholar]

- Bello, C.; Roseth, A.; Guardiola, J.; Reenaers, C.; Ruiz-Cerulla, A.; Van Kemseke, C.; Arajol, C.; Reinhard, C.; Seidel, L.; Louis, E. Usability of a home-based test for the measurement of fecal calprotectin in asymptomatic IBD patients. Dig. Liver Dis. 2017, 49, 991–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haisma, S.M.; Galaurchi, A.; Almahwzi, S.; Adekanmi Balogun, J.A.; Muller Kobold, A.C.; van Rheenen, P.F. Head-to-head comparison of three stool calprotectin tests for home use. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0214751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heida, A.; Knol, M.; Kobold, A.M.; Bootsman, J.; Dijkstra, G.; van Rheenen, P.F. Agreement between home-based measurement of stool calprotectin and ELISA results for monitoring inflammatory bowel disease activity. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 15, 1742–1749.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Age (Years) | Mean | SD | Range | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 52.4 | 13.67 | 23–81 | |||

| Sex | Frequency | Percentage (%) | |||

| Female | 51 | 63.0 | |||

| Male | 30 | 37.0 | |||

| Medications a | |||||

| Oral 5-ASA b | 68 | 84.0 | |||

| Azathioprine | 10 | 12.3 | |||

| Topical Rectal Therapies c | 15 | 18.5 | |||

| FNo Medications | 15 | 18.5 | |||

| Last Follow-up | |||||

| 6 Months to 1 Year | 43 | 53.1 | |||

| 1 Year to 2 Years | 22 | 27.2 | |||

| >2 Years | 16 | 19.8 | |||

| Partial Mayo Score (n = 81) | |||||

| Remission (<2) | 64 | 79.0 | |||

| Mild (2–4) | 13 | 16.0 | |||

| Moderate (5–6) | 2 | 2.5 | |||

| Severe (7–9) | 2 | 2.5 | |||

| Endoscopic Mayo Score (n = 22) | |||||

| No Active Disease (0) | 4 | 18.2 | |||

| Mild (1) | 9 | 40.9 | |||

| Moderate (2) | 6 | 27.2 | |||

| Severe (3) | 3 | 13.6 | |||

| Modified Sutherland Index (n = 81) | |||||

| Remission (0–2) | 54 | 66.7 | |||

| Mild (3–5) | 17 | 21.0 | |||

| Moderate (6–11) | 10 | 12.3 | |||

| Severe (12+) | 0 | 0 | |||

| MARS-5 Questionnaire (n = 66) | |||||

| Adherent (>20) | 57 | 86.4 | |||

| Non-adherent (=< 20) | 9 | 13.6 | |||

| Laboratory Results (n = 81) | Normal Values a | Median | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fecal Calprotectin | <50 µg/g | 142.00 | 379.18 | 658.10 |

| C-Reactive Protein | <8.0 mg/L | 1.75 | 4.85 | 7.41 |

| Hemoglobin * | 120–160 g/L | 142.00 | 140.44 | 11.93 |

| Mean Corpuscular Volume | 80–100 fL | 90.00 | 89.80 | 6.08 |

| Leukocytes | 4.0–11.0 × 109/L | 6.40 | 6.89 | 2.03 |

| Platelets | 140–400 × 109/L | 252.00 | 254.86 | 68.59 |

| Serum Iron * | 8–35 umol/L | 14.00 | 15.69 | 6.74 |

| Ferritin * | 20–300 umol/L | 68.00 | 93.98 | 81.52 |

| Creatinine * | 40–100 umol/L | 75.00 | 76.69 | 20.01 |

| Albumin | 30–45 g/L | 43.00 | 42.84 | 2.56 |

| Alkaline Phosphatase | 40–120 U/L | 73.00 | 86.57 | 46.76 |

| Alanine Transaminase | <50 U/L | 26.00 | 31.54 | 25.87 |

| Partial Mayo Category | Remission (n = 64) | Mild (n = 13) | Moderate (n = 2) | Severe (n = 2) | F (4, 81) | η2 | ||||

| Median | Mean (SD) | Median | Mean (SD) | Median | Mean (SD) | Median | Mean (SD) | |||

| FCP | 109.0 | 257.0 (419.2) | 267.0 | 753.7 (1149.8) | 1247.0 | 1247.0 (169.7) | 1231.5 | 1231.5 (1706.2) | 5.12 * | 0.16 |

| Sutherland Index Category | Remission (n = 54) | Mild (n = 17) | Moderate (n = 10) | Severe | F (2, 81) | η2 | ||||

| Median | Mean (SD) | Median | Mean (SD) | Median | Mean (SD) | Median | Mean (SD) | |||

| FCP | 72.5 | 217.4 (403.5) | 197.0 | 530.5 (888.2) | 782.5 | 872.1 (843.7) | n/a | n/a | 5.52 * | 0.12 |

| Endoscopic Mayo Category | No Active Disease (n = 4) | Mild (n = 9) | Moderate (n = 7) | Severe (n = 3) | F (2, 16) | η2 | ||||

| Median | Mean (SD) | Median | Mean (SD) | Median | Mean (SD) | Median | Mean (SD) | |||

| FCP | 243.0 | 415.3 (356.7) | 361.0 | 497.1 (364.2) | 804.0 | 1034.9 (766.9) | 2438.0 | 2821.7 (1201.4) | 13.02 * | 0.65 |

| Variable | β | S.E. | Exp(β) | 95% CI | p | R2N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FCP | 0.003 | 0.001 | 1.003 | 1.000, 1.006 | 0.023 | |

| CRP | 0.058 | 0.042 | 1.060 | 0.977, 1.149 | 0.163 | |

| Sutherland Index Active Disease | 1.164 | 0.579 | 3.203 | 1.030, 9.959 | 0.044 | |

| 0.440 | ||||||

| FCP (250 µg/g) | 2.482 | 0.647 | 11.964 | 3.300, 43.382 | <0.001 | |

| CRP | 0.070 | 0.043 | 1.072 | 0.986, 1.166 | 0.104 | |

| Sutherland Index Active Disease | 1.396 | 0.583 | 4.039 | 1.288, 12.660 | 0.017 | |

| 0.473 | ||||||

| FCP (150 µg/g) | 1.763 | 0.556 | 5.830 | 1.962, 17.326 | 0.002 | |

| CRP | 0.056 | 0.038 | 1.057 | 0.980, 1.140 | 0.148 | |

| Sutherland Index Active Disease | 1.288 | 0.557 | 5.357 | 1.218, 10.798 | 0.021 | |

| 0.394 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

MacKay, S.; Parsons, D.; Hagerman, C.; Lytvyak, E.; Dieleman, L.; Hoentjen, F.; Kroeker, K.; Peerani, F.; Wong, K.; Gozdzik, M.; et al. The Impact of Proactive Fecal Calprotectin Collection in an Outreach Protocol for Biologic-Naïve Ulcerative Colitis Patients–Ulcerative Colitis Clinical Outreach (UCCO). Diseases 2026, 14, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases14010002

MacKay S, Parsons D, Hagerman C, Lytvyak E, Dieleman L, Hoentjen F, Kroeker K, Peerani F, Wong K, Gozdzik M, et al. The Impact of Proactive Fecal Calprotectin Collection in an Outreach Protocol for Biologic-Naïve Ulcerative Colitis Patients–Ulcerative Colitis Clinical Outreach (UCCO). Diseases. 2026; 14(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases14010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleMacKay, Scott, Denise Parsons, Candace Hagerman, Ellina Lytvyak, Levinus Dieleman, Frank Hoentjen, Karen Kroeker, Farhad Peerani, Karen Wong, Michal Gozdzik, and et al. 2026. "The Impact of Proactive Fecal Calprotectin Collection in an Outreach Protocol for Biologic-Naïve Ulcerative Colitis Patients–Ulcerative Colitis Clinical Outreach (UCCO)" Diseases 14, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases14010002

APA StyleMacKay, S., Parsons, D., Hagerman, C., Lytvyak, E., Dieleman, L., Hoentjen, F., Kroeker, K., Peerani, F., Wong, K., Gozdzik, M., Oguro, K., McMullen, T., & Halloran, B. (2026). The Impact of Proactive Fecal Calprotectin Collection in an Outreach Protocol for Biologic-Naïve Ulcerative Colitis Patients–Ulcerative Colitis Clinical Outreach (UCCO). Diseases, 14(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases14010002