Benefits of Traditional Medicinal Plants to African Women’s Health: An Overview of the Literature

Abstract

1. Introduction

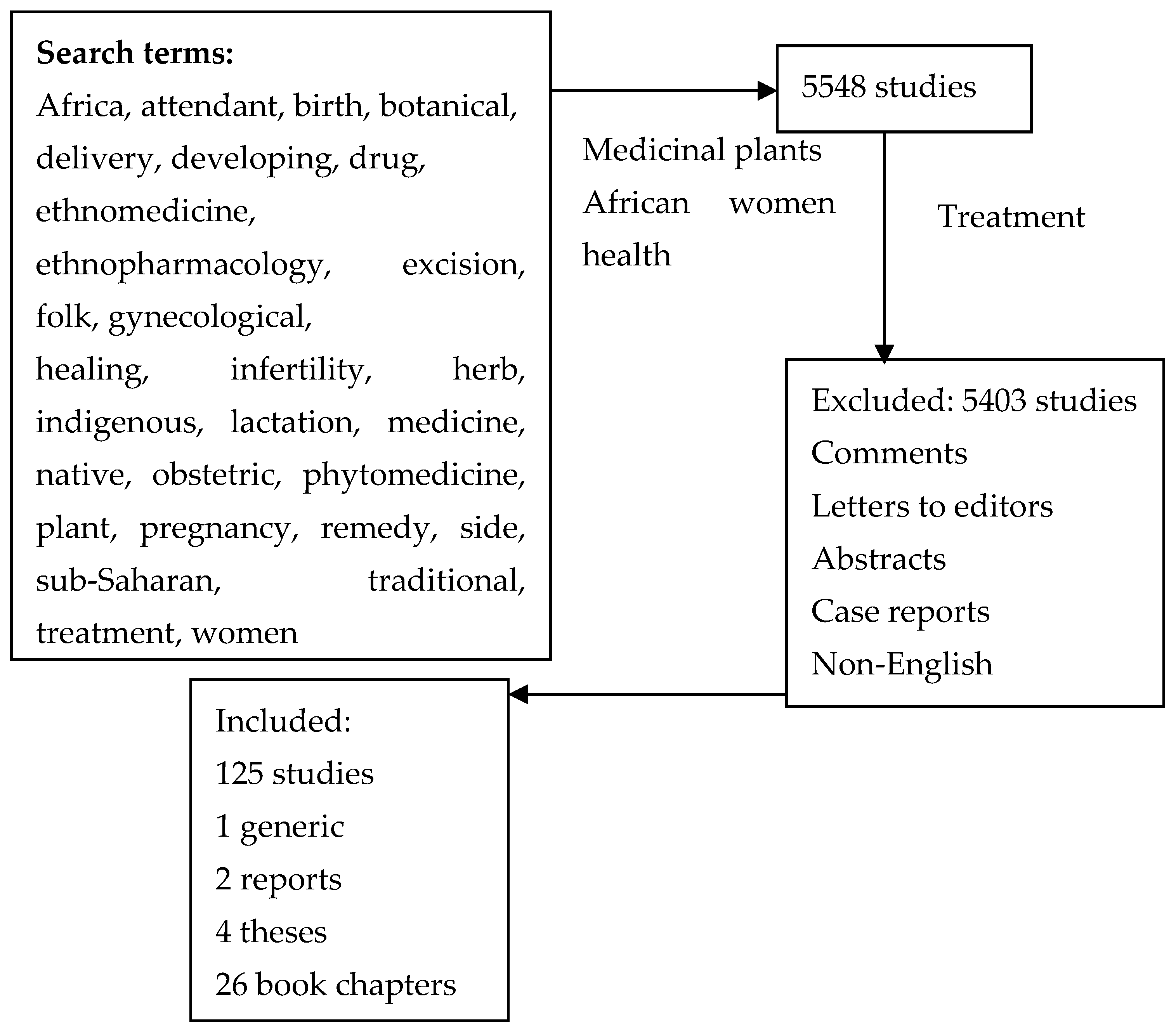

2. Materials and Methods

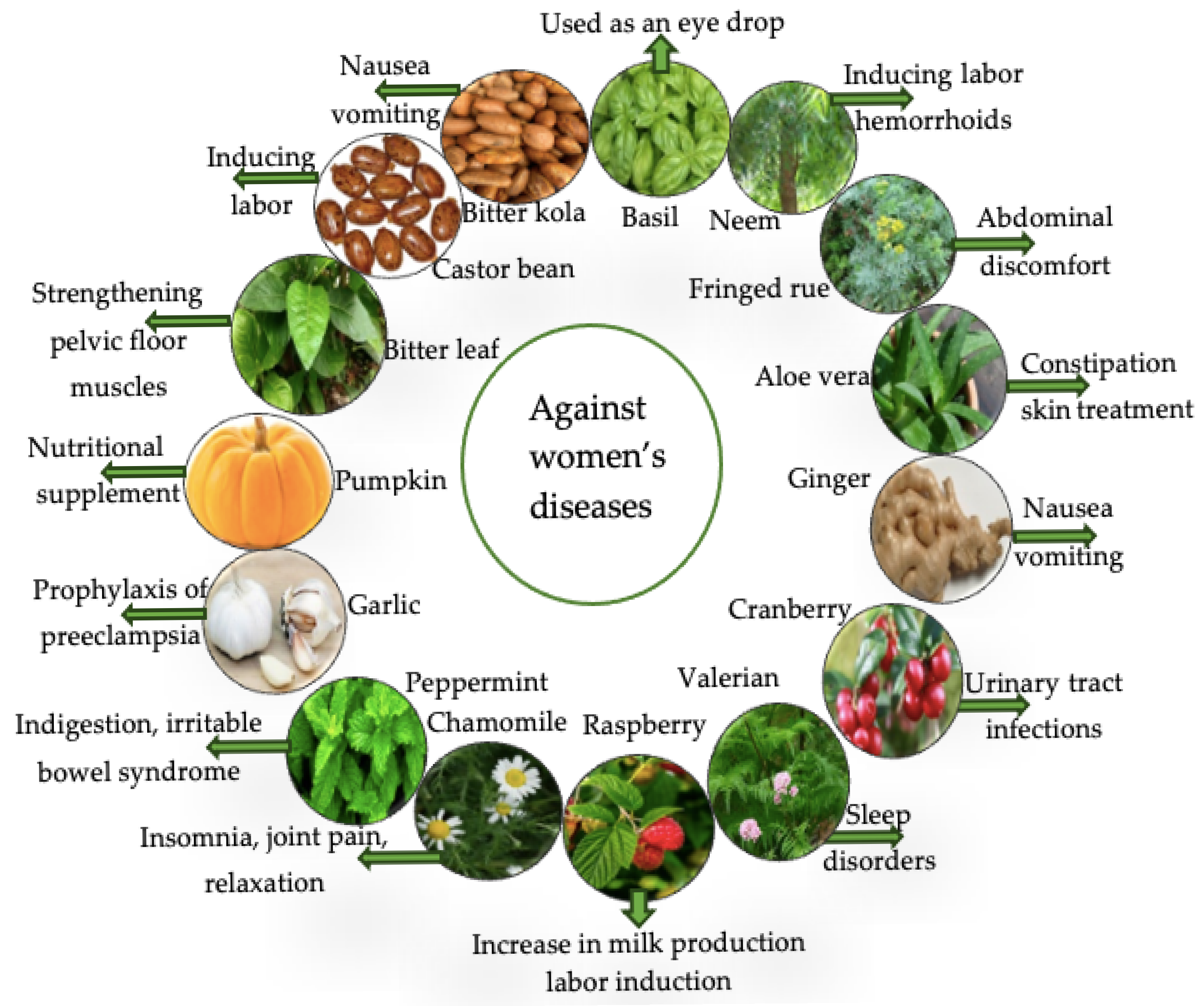

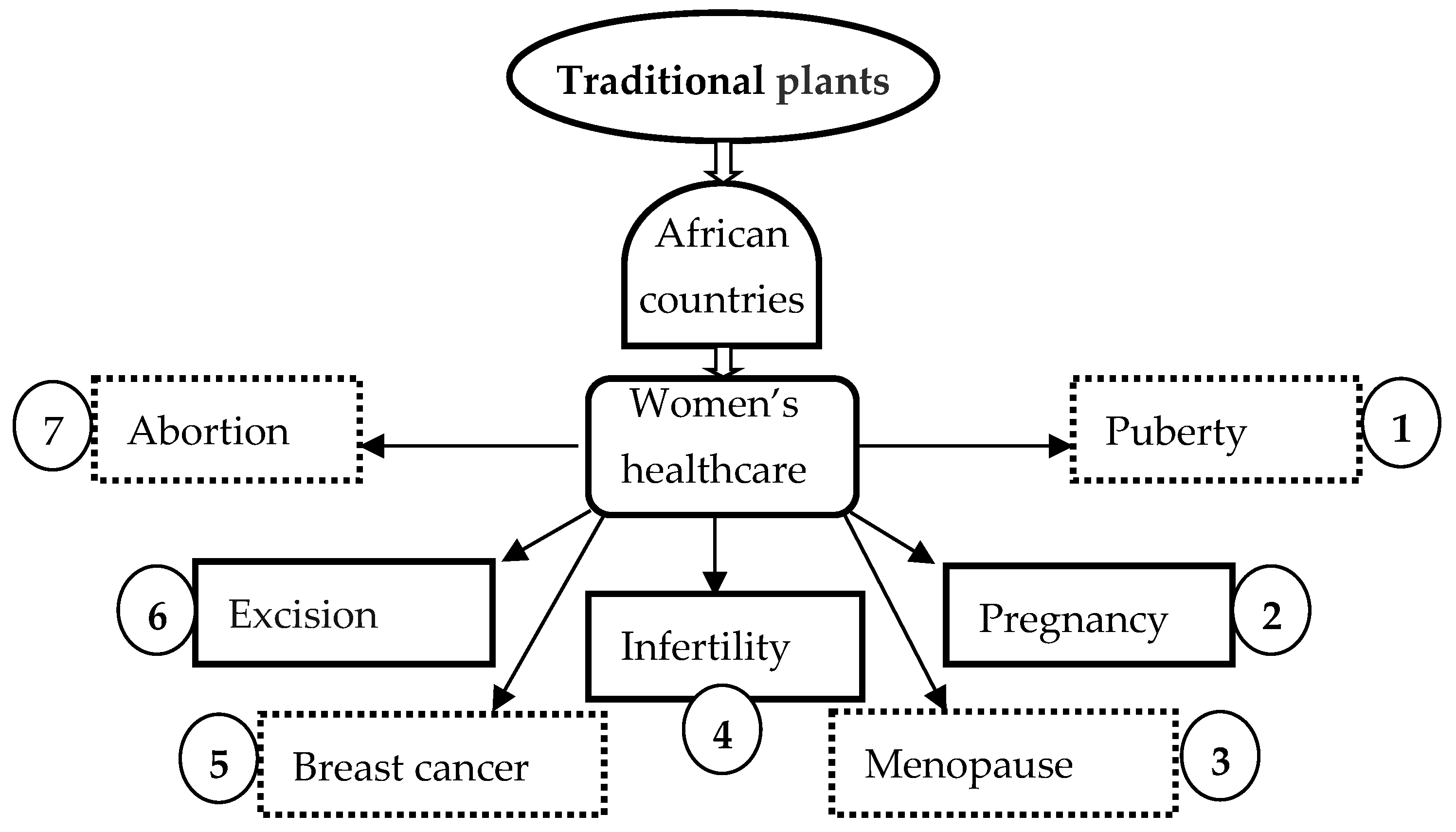

3. Traditional Herbal Medicines for the Management of Major Diseases Affecting African Women

3.1. Puberty

3.2. Pregnancy

3.3. During Labor and the Postpartum Recovery Period

3.3.1. Expelling Placenta

3.3.2. For Postpartum Hemorrhage

3.3.3. For Postpartum Contractions

3.3.4. Help to Breastfeeding

3.3.5. Treatment of Genitalia

3.4. Menopause

3.5. Infertility

3.6. Uterine Fibroids and Matrix Troubles

3.7. Breast Cancer

3.8. Abortion

3.9. Excision

| Country | Plant Names | Usage/Indication | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benin | Violet tree (Securidaca longipedunculata Fresen.), Buckbrush (Dichapetalum madagascariense Poir.), Tabaco cimarron (Schwenckia americana L.), Sierra leone (Pavetta corymbosa F.N. Williams), African peach (Sarcocephalus latifolius (Sm.) E.A.Bruce), Spanish shawl (Heterotis rotundi- folia (Sm.) Jacq.-Fél.), Roundleaf sensitive pea (Chamaecrista rotundifolia (Pers.) Greene), Boundary tree (Newbouldia laevis (P. Beauv.) Seem) | Consumed during pregnancy: strengthening | [17] |

| Cameroon | Lambe pundo (Senecio biafrae (Oliv. & Hiern) C.Jeffrey. | For the treatment of female infertility, painful menstruations, horn’s gulps acid reflux | [69] |

| Cameroon | a-guare-(a)nsra (Eremomastax speciosa (Hochst.) Cufod.), Aframomum (Aframomum letestuanum Gagnep), White Weed (Ageratum conyzoides L.), Ooso (Justicia insularis T. Anderson), West African aloe (Aloe buettneri A. Berger) | For the treatment of female infertility | [69] |

| Cameroon | Lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus (DC.) Stapf), Ragleaf, thickhead (Crassocephalum bauchiense (Hutch.) Milne-Redh.) | Swelling of legs and ankles, cleaning of the baby | [16] |

| Cameroon | West African aloe (Morton) | Swelling of legs and ankles, facilitate baby delivery, baby cleaning purposes, urogenital infections, postpartum abdominal pain. | [16] |

| Cameroon | Heartleaf fanpetals (Sida veronicifolia Lam.) | Swelling of legs and ankles or postpartum abdominal pain, in reducing pains of labor during or after childbirth, facilitation of delivery, body sweats, bleeding during pregnancy | [16] |

| Cameroon | Wandering jew (Commelina benghalensis L.) | Facilitate baby delivery, swelling of legs and ankles | [16] |

| Cameroon | Roselle (Hibiscus noldeae Baker f.) | Facilitate baby delivery, urogenital infections, postpartum abdominal pain; swelling of legs and ankles, cleaning of the baby | [16] |

| Cameroon | Neverdie (Kalanchoe crenata (Andrews) Haw.), Chinese hibiscus (Hibiscus rosa- sinensis L.) | Facilitate baby delivery | [16] |

| Côte d’Ivoire Nigeria | Scent leaf (Ocimum gratissimum L.) | Abdominal pain, loss of appetite, fever, cold and catarrh | [92,93] |

| Egypt | Peppermint (Mentha × piperita L.) | Gastrointestinal disorders, common cold, muscle pain, headache | [94,95] |

| Egypt | Anise (Pimpinella anisum L.) | Nausea, vomiting, abdominal colic | [94,95] |

| Egypt | Fenugreek (Trigonella foenumgraecum) | Stimulates uterine contractions, milk production, blood sugar levels reduction, stomachache | [94,95] |

| Egypt | Aniseed (Anisum odoratum Raf.), fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum L.), Ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe), garlic (Allium sativum L.), green tea (Camellia sinensis L. Kuntze), and peppermint (Mentha × pepirita L.) | To treat abdominal colic during pregnancy, nausea, vomiting, and headache | [94] |

| Ethiopia | Ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe) | Pregnancy emesis, morning/motion sickness | [22,96] |

| Etiopia Nigeria | Garlic (Allium sativum L.) | Pregnancy symptoms | [22,97] |

| Ethiopia Nigeria | Pumpkins (Cucurbita pepo L.) | Nutritional supplement for pregnancy | [96,97] |

| Ethiopia | Fringed rue (Ruta chalepensis L.) | Nausea, vomiting, common cold, stomachache | [22,96] |

| Ethiopia | Eucalyptus (Eucalyptus globulus Labill.) | Fever, upset stomach, help loosen coughs | [22,98] |

| Ethiopia | Fringed rue (Ruta chalepensis L.), Eucalyptus (Eucalyptus globulus Labill.), Ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe), Garlic (Allium sativum L.) | Pregnant women: for treatment of nausea, morning sickness, vomiting, cough, nutritional deficiency | [98] |

| Ethiopia | Garlic (Allium sativum L.), Ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe), Fringed rue (Ruta chalepensis L.), Eucalyptus (Eucalyptus globulus Labill.), Basil (Ocimum lamiifolium Hochst) | Pregnant women: management of nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, common cold, fever | [22] |

| Ethiopia | Ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe), Basil (Ocimum lamiifolium Hochst.) | Common cold, inflammation | [99] |

| Ethiopia | Ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe) | By pregnant mothers: morning sickness, cough during common old, aid digestion | [20] |

| Ethiopia | Garlic (Allium Sativum L.) | By pregnant mothers: common cold, flu, prevention of preeclampsia | [20] |

| Ethiopia | Basil (Ocimum lamiifolium Hochst.) | By pregnant mothers: headache, fever, hypertension, and flank pain | [20] |

| Ethiopia | Fringed rue (Ruta chalepensis L.) | By pregnant mothers: headache, fever, and cold | [20] |

| Ethiopia | Thyme (Thymus schimperi Ronniger) | By pregnant mothers: cough, stomach pain, and as a flavoring agent | [20] |

| Ghana | Coffee senna (Senna occidentalis (L.) Link), Common wireweed (Sida acuta Burm.f.) Giant cola (Cola gigantea A. Chev.) | To ease labor and improve fetal outcomes | [100] |

| Ghana | Groundnut tree (Ricinodendron heudelotii (Baill.) Pierre ex Heckel), Oil palm (Elaeis guineensis Jacq.), Spice tree (Xylopia aethiopica (Dunal) A. Rich.), Boundary tree (Newbouldia laevis (P. Beauv.) Seem, African tulip tree (Spathodea campanulata P. Beauv.), Giant sword fern (Nephrolepis biserrata (Sw.) Schott J.J.deWilde), African dragon tree (Dracaena arborea (Willd.) Link, Senegal Mahogany (Khaya senegalensis A. Juss) | Consumed during pregnancy: strengthening | [17] |

| Ghana | Trade banayi (Trichilia monadelpha (Thonn.), Bitter cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) | Consumed during pregnancy: antiemetic | [17] |

| Ghana | Black Afara (Terminalia ivorensis A.Chev) | Consumed during pregnancy: strengthening, to treat anemia | [17] |

| Kenya | Perennial soybean (Glycine wightii (Wight & Arn.) J.A. Lackey), Noseburn (Tragia brevipes Pax.) | To treat breast cancer | [80] |

| Kenya Nigeria | Castor oil (Ricinus communis L.) | Pregnant: delayed/protracted labor, retained after birth, postpartum hemorrhage, constipation and labor induction | [97,101] |

| Mali | English tea bush (Lippia chevalierii Moldenke.) | During pregnancy: well-being, nutrition or as a dietary supplement, common cold | [15,19] |

| Mali | Kinkeliba (Combretum micranthum G. Don) | During pregnancy: symptoms of malaria, edema, nausea | [15,19] |

| Mali | African locust bean (Parkia biglobosa (Jacq.) R.Br. ex G.Don) | During pregnancy: well-being, urinary tract infection, symptoms of malaria | [15,19] |

| Mali | Guiziga, Mofou (Vepris heterophylla (Engl.) Letouzey) | During pregnancy: symptoms of malaria, constipation, edema | [15,19] |

| Mali | Nigerian stylo (Stylosanthes erecta P.Beauv.) | During pregnancy: symptoms of malaria Tiredness | |

| Mali | Hog plum (Ximenia americana L.) | During pregnancy: well-being To increase appetite, heartburn | [15,19] |

| Mali | English false abura (Mitragyna inermis (Willd.) Kuntze) | During pregnancy: symptoms of malaria, Urinary tract infection | [15,19] |

| Mali | Dooki in Pulaar (Combretum glutinosum Perr. ex DC.) | During pregnancy: symptoms of malaria tiredness | [15,19] |

| Mali | Manjanda marm (Opilia amentacea Roxb.) | During pregnancy: Symptoms of malaria, to increase appetite, tiredness | [15,19] |

| Mali | Kola tree (Cola cordifolia) | During pregnancy: Well-being, symptoms of malaria, to increase appetite | [15] |

| Mali | Natal mahogany (Trichilia emetica Vahl) | During pregnancy: malaria tiredness | [15,19] |

| Morocco | Vervain (Verbena officinalis L.), cresson (Nasturtium officinale R.Br.), Madder (Rubia tinctorum L.), fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum L.), Cinnamon (Cinnamomum verum J.Presl), ginger (Zingiber officinale) | Mothers who gave birth in the last 5 years: To get back in shape after delivery, facilitate child birth, vomiting, increase breast milk secretion | [102] |

| Nigeria | Bitter leaf (Vernonia amygdalina (Delile) Sch.Bip.) | Emesis, fever, constipation, loss of appetite during pregnancy | [92,103] |

| Nigeria | Bitter kola (Garcinia kola Heckel) | Nausea, vomiting | [97,104] |

| Nigeria | Nim tree (Azadirachta indica A. Juss.) | Pain, anemia, malaria, piles, make the unborn baby strong | [97,103] |

| Nigeria | Aloe vera (Aloe vera (L.) Burm.f.) | Pregnancy symptoms, skin treatment | [97,104] |

| Nigeria | Cannabis (Cannabis sativa L.) | Pain, fever, catarrh, loss of appetite, labor induction/speed up | [92,105] |

| Nigeria | Moringa (Moringa oleifera Lam.) | Fever, cough, emesis, helminths, diarrhea, diuretic | [97,104] |

| Nigeria | Camwood (Baphia nitida G. Lodd.) | Therapeutic meal | [93,97] |

| Nigeria | Palm kernel oil (Elaeis guineensis Jacq.) | Pregnancy symptoms | [103,104] |

| Nigeria | Gum arabic tree (Acacia nilotica (L.) Willd. ex) | Postpartum wound healing | [106] |

| Nigeria | Moshi medicine (Guiera senegalensis J.F.Gmel) | Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea and general well-being in maternal healthcare | [106] |

| Sierra Leone | Angled luffa (Luffa acutangula Roxb) ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe), lime (Citrus aurantiifolia (Christm.) Swingle) | Urinary tract infections, pedal edema, to improve fetal outcomes | [107] |

| South Africa | Dassiepis (Hippobromus alata Eckl. & Zeyh.) | Combined with Bakbos for cleansing after birth | [108] |

| South Africa | Moerbossie (Anacampseros albissima Marloth) | To cleanse womb after birth | [108] |

| South Africa | Isihlambezo | Quick and painless delivery, reduced vaginal discharge, reduce placental size, drain edema, fetal well-being | [109,110] |

| South Africa | Black monkey thorn (Acacia burkei Benth.) | To ease labor and labor pain | [7] |

| South Africa | Umpendulo (Acalypha villicaulis Hochst. ex A.Rich.) | During her first menstruation to shorten menstruation period, to regulate blood flow for next consecutive menses dysmenorrhea, and during pregnancy to ensure safe pregnancy and an uncomplicated delivery | [7] |

| South Africa | Creeping starbur (Acanthospermum glabratum (DC.) Wild) | To treat cervical pains during pregnancy | [7] |

| South Africa | Blue sweetberry (Bridelia cathartica Bertol.) | Dysmenorrhoea and infertility, to treat menorrhagia | [7] |

| South Africa | Corkwood (Commiphora neglecta I. Verd.) | To treat dysmenorrhea, menorrhagia, infertility, oligomenorrhoea, premature birth, and to cleanse the blood when pregnant | [7] |

| South Africa | Small-leaved Rattle-pod (Crotalaria monteiroi Trubert ex Baker f.) | To treat dysmenorrhea, menorrhagia, infertility, oligomenorrhoea, premature birth, and to cleanse the blood when pregnant | [7] |

| South Africa | Giant Dune Sedge (Cyperus natalensis Hochst. ex. C. Krauss) | To treat menorrhagia | [7] |

| South Africa | Hairy star-apple (Doispyros villosa (L.) De Winter) | For dysmenorrhoea | [7] |

| South Africa | Dwarf coral tree (Erythrina humeana Spreng.) | Dysmenorrhea and once a day for infertility; to prevent miscarriage as soon as a person knows they are pregnant | [7] |

| South Africa | Natal guarri (Euclea natalensis A.DC.) | Pregnant women for blood purification | [7] |

| South Africa | Common bushweed (Flueggea virosa Roxb. Ex Willd Royle) | For antepartum hemorrhage and to prevent premature birth. | [7] |

| South Africa | African Mangosteen (Garcinia livingstonei T. Anderson) | To treat dysmenorrhea and postpartum hemorrhage | [7] |

| South Africa | Crossberry (Grewia occidentalis L.) | To treat dysmenorrhoea, menorrhagia, infertility, oligomenorrhoea, premature birth, and to cleanse the blood when pregnant | [7] |

| South Africa | Red spikethorn (Gymnosporia senegalensis Loes.) | Used as an enema and to treat infertility | [7] |

| South Africa | Gombossie (Hermannia boraginiflora Hook.) | To treat dysmenorrhoea and during pregnancy to ease labor | [7] |

| South Africa | Lala palm (Hyphaene coriacea Gaertn.) | For dysmenorrhoea, infertility, after birth pains, postpartum bleeding, and to ease labor | [7] |

| South Africa | Qtar-grass (Hypoxis cf. longifolia Baker) | To treat menorrhagia | [7] |

| South Africa | Star flower (Hypoxis hemerocallidea Fisch., C.A.Mey. & Avé-Lall.) | For dysmenorrhagia | [7] |

| South Africa | Sausage tree (Kigelia africana (Lam.) Benth.) | For blood cleansing and pelvic pains during pregnancy | [7] |

| South Africa | Showy plane (Ochna natalitia Walp.) | To treat dysmenorrhoea, menorrhagia and infertility taken for after-birth pain. To ease labor and reduce delivery complications. To treat menorrhagia, dysmenorrhoea and for blood purification in a pregnant woman. | [7] |

| South Africa | Erect prickly pea (Opuntia stricta (Haw.) Haw. | Pregnant at the third trimester to dilate the cervix and to cleanse blood | [7] |

| South Africa | Weeping resintree (Ozoroa engleri R.Fern & A. Fern. | To treat dysmenorrhoea and after birth pains | [7] |

| South Africa | Rhodesian blackwood (Peltophorum africanum Sond.) | For dysmenorrhoea and blood cleansing when pregnant. | [7] |

| South Africa | Wild Buttercup (Ranunculus multifidus Forssk.) | To treat infertility, to cleanse blood when pregnant and to ease labor | [7] |

| South Africa | Baboon grape (Rhoicissus digitata Gilg & M.Brandt) | To treat dysmenorrhoea and infertility, amenorrhoea. | [7] |

| South Africa | Sapium integerrimum Hochst. | For menstruation and dysmenorrhoea | [7] |

| South Africa | Jelly plum (Sclerocarya birrea Hochst.) | For pregnancy to induce abortion | [7] |

| South Africa | Hairy coastal currant (Searsia nebulosa (Schönland) Moffett) | For dysmenorrhoea and infertility | [7] |

| South Africa | Canary creeper (Senecio deltoideus Less) | To treat infertility. | [7] |

| South Africa | Ichazampuk-ane (Senecio serratuloides DC.) | To treat infertility, to cleanse blood when pregnant and to ease labor | [7] |

| South Africa | Toad tree (Tabernaemontana elegans Stapf) | Dysmenorrhoea and infertility | [7] |

| South Africa | Natal mahogany (Trichilia emetica Vahl) | To induce abortion at a first trimester of pregnancy used to massage the belly of a woman during labor and reduce pains | [7] |

| South Africa | Heart-leaved brooms and brushes (Acalypha brachiata Krauss) | For contraception | [111] |

| South Africa | Bitter aloe, tap aloe, red aloe (Aloe spp.) | For contraception | [112] |

| South Africa | Holy thistle (Centaurea benedicta (L.) L.) | For contraception | [113] |

| South Africa | Blue bitter-tea (Gymnanthemum myrianthum (Hook.f.) H. Rob) | For contraception | [114] |

| South Africa | Bitter karkoe (Kedrostis nana Cogn.) | For contraception | [115] |

| South Africa | Hell-fire bean (Mucuna coriacea Baker) | For contraception | [116] |

| South Africa | Sausage tree (Kigelia africana (Lam.) Benth.) | For contraception | [7] |

| South Africa | Soap-nettle (Pouzolzia mixta Solms) | For contraception | [117] |

| South Africa | Cauliflower (Salsola tuberculatiformis Botsch.) | For contraception | [118] |

| South Africa | Dwarf Mexican (Schkuhria pinnata (Lam.) Kuntze | For contraception | [117] |

| South Africa | Violet tree (Securidaca longepedunculata Fresen.) | For contraception | [114] |

| South Africa | Marula (Sclerocarya Birrea Hochst.) | Female infertility | [23] |

| South Africa | Beggar’s tick (Bidens pilosa L.) | Menstrual disorder | [23] |

| South Africa | Coast silver oak (Brachylaena discolor DC.) | Female infertility | [23] |

| South Africa | Misbeksiektebos (Geigeria aspera Harv.) | Period pains | [23] |

| South Africa | Paintbrush flower (Kleinia longiflora DC.) | Menstrual disorder | [23] |

| South Africa | Pawpaw (Carica papaya L.) | Abortion | [23] |

| South Africa | Bushveld saffron (Elaeodendron transvaalense (Burtt Davy) R.H.Archer) | Female infertility | [23] |

| South Africa | Paper reed (Cyperus papyrus L.) | Menstrual disorder | [23] |

| South Africa | Prostrate Sandmat (Chamaesyce Prostrata Aiton) | Womb problem | [23] |

| South Africa | Candelabra tree (Euphorbia ingens E.Mey. ex Boiss.) | Breast cancer | [23] |

| South Africa | Purging nut (Jatropha curcas L.) | Impotence, vaginal candidiasis | [23] |

| South Africa | Cork bush (Mundulea Sericea (Wild.) A.Chev.) | Menstrual disorders | [23] |

| South Africa | African blackwood (Peltophorum africanum Sond.) | Female infertility, post-partum | [23] |

| South Africa | Spanish gold (Sesbania punicea (Cav.) Benth.), Lavender tree (Heteropyxis Transvaalensis Schinz.) | Menstrual disorder | [23] |

| South Africa | Satin squill (Drimia elata Jacq. ex Willd.) | Female infertility; impotence | [23] |

| South Africa | Star-grass (Hypoxis obtusa Burch.) | Female infertility | [23] |

| South Africa | African soapberry (Phytolacca dodecandra L’Hér.) | Female infertility; menstrual disorder | [23] |

| South Africa | African sandalwood (Osyris lanceolata Hochst. & Steud.) | Impotence; menstrual disorder | [23] |

| South Africa | Habanero pepper (Capsicum chinense Jacq.) | Period pains | [23] |

| South Africa | Hell-fire bean (Mucuna coriacea Baker. | For contraception | [116] |

| South Africa | Sausage tree (Kigelia africana (Lam.) Benth.) | For contraception | [7] |

| South Africa | Soap-nettle (Pouzolzia mixta Solms), Dwarf Mexican (Schkuhria pinnata (Lam.) Kuntze ex Thell.) | For contraception | [117] |

| Cauliflower (Salsola tuberculatiformis Botsch.), Saltwort | For contraception | [118] | |

| South Africa | Violet tree (Securidaca longipedunculata Fresen.) | For contraception | [114] |

| Zimbabwe | Snuggle-leaf (Pouzolzia mixta Sohms) Okra (Abelmoschus esculentus Moench) | For widening of birth canal, labor induction, nutritional supplement | [105] |

| Zimbabwe | Makoni (Fadogia ancylantha Schweinf.) Tea Bush (Abelmoschus esculentus Moench) Okra Chir pine (Pinus roxburghii Sarg.) | To facilitate childbirth, for “widening of birth canal” | [119] |

4. Scientific Evidence for the Efficacy of the Most Reported Herbal Remedies (Castor Bean, Garlic, Ginger, Pumpkin)

4.1. Castor Bean

4.2. Garlic

4.3. Ginger

4.4. Pumpkin

5. Risks Possibly Associated with Herbal Treatments for African Women

5.1. Quality and Safety Concerns

5.2. Self-Medication and Lack of Information on the Use of Plants

5.3. Risks of Over- or Under-Dosage and Toxicity

5.4. Risks Associated with the Use of Plants by Pregnant Women

5.5. Suggestions for Guidance

5.5.1. Quality Aspects

5.5.2. Particular Precautions for Pregnancy and Menopause

5.5.3. Pharmacovigilance Aspects

6. Deficiencies, Development Challenges and Possible Strategies

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahmed, S.M.; Nordeng, H.; Sundby, J.; Aragaw, Y.A.; de Boer, H. The use of medicinal plants by pregnant women in Africa: A systematic review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 224, 297–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Towns, A.M.; Ruysschaert, S.; van Vliet, E.; van Andel, T. Evidence in support of the role of disturbance vegetation for women’s health and childcare in Western Africa. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2014, 10, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gyasi, R.M.; Abass, K.; Adu-Gyamfi, S.; Accam, B.T.; Nyamadi, V.M. The capabilities of nurses for complementary and traditional medicine integration in Africa. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2018, 24, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mothupi, M.C. Use of herbal medicine during pregnancy among women with access to public healthcare in Nairobi, Kenya: A cross-sectional survey. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2014, 14, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Odedina, S.; Agwai, I.; Ojengbede, O.; Huo, D.; Olopade, O.I. Traditional medicine usage among adult women in Ibadan, Nigeria: A cross-sectional study. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2020, 20, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OMS. Régional de l’Afrique, C. Relever le défi en Matière de Santé de la Femme en Afrique: Rapport de la Commission sur la Santé de la Femme dans la Région Africaine; (Document AFR/RC63/8) (No. AFR/RC63/R4); Bureau régional de l’Afrique: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- De Wet, H.; Ngubane, S. Traditional herbal remedies used by women in a rural community in northern Maputaland (South Africa) for the treatment of gynaecology and obstetric complaints. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2014, 94, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantuan, V.; Sannomiya, M. Women and medicinal plants: A systematic review in the field of ethnobotany. Acta Sci. Biol. Sci. 2024, 46, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, M.; Liu, X.; Ren, Y.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, L.; Liang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, T.; Wang, W.; Mei, Z. Comparison of herbal medicines used for women’s menstruation diseases in different areas of the world. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 12, 751207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Andel, T.; de Boer, H.J.; Barnes, J.; Vandebroek, I. Medicinal plants used for menstrual disorders in Latin America, the Caribbean, sub-Saharan Africa, South and Southeast Asia and their uterine properties: A review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 155, 992–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veale, D.; Furman, K.; Oliver, D. South African traditional herbal medicines used during pregnancy and childbirth. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1992, 36, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Kooi, R.; Theobald, S. Traditional medicine in late pregnancy and labour: Perceptions of Kgaba remedies amongst the Tswana in South Africa. Afr. J. Tradit. Complement. Altern. Med. 2006, 3, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banda, Y.; Chapman, V.; Goldenberg, R.L.; Stringer, J.S.; Culhane, J.F.; Sinkala, M.; Vermund, S.H.; Chi, B.H. Use of traditional medicine among pregnant women in Lusaka, Zambia. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2007, 13, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakeye, T.O.; Adisa, R.; Musa, I.E. Attitude and use of herbal medicines among pregnant women in Nigeria. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2009, 9, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nergard, C.S.; Ho, T.P.T.; Diallo, D.; Ballo, N.; Paulsen, B.S.; Nordeng, H.; ethnomedicine. Attitudes and use of medicinal plants during pregnancy among women at health care centers in three regions of Mali, West-Africa. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2015, 11, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yemele, M.; Telefo, P.; Lienou, L.; Tagne, S.; Fodouop, C.; Goka, C.; Lemfack, M.; Moundipa, F. Ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants used for pregnant women’s health conditions in Menoua division-West Cameroon. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 160, 14–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Towns, A.; Van Andel, T. Wild plants, pregnancy, and the food-medicine continuum in the southern regions of Ghana and Benin. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 179, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hajj, M.; Holst, L. Herbal medicine use during pregnancy: A review of the literature with a special focus on sub-Saharan Africa. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordeng, H.; Al-Zayadi, W.; Diallo, D.; Ballo, N.; Paulsen, B.S. Traditional medicine practitioners’ knowledge and views on treatment of pregnant women in three regions of Mali. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2013, 9, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kahssay, S.W.; Tadege, G.; Muhammed, F. Self-medication practice with modern and herbal medicines and associated factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care at Mizan-Tepi University Teaching Hospital, Southwest Ethiopia. Heliyon 2022, 8, e10398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thipanyane, M.P.; Nomatshila, S.C.; Oladimeji, O.; Musarurwa, H. Perceptions of pregnant women on traditional health practices in a rural setting in South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laelago, T.; Yohannes, T.; Lemango, F. Prevalence of herbal medicine use and associated factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care at public health facilities in Hossana Town, Southern Ethiopia: Facility based cross sectional study. Arch. Public Health 2016, 74, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semenya, S.; Maroyi, A.; Potgieter, M.; Erasmus, L. Herbal medicines used by Bapedi traditional healers to treat reproductive ailments in the Limpopo Province, South Africa. Afr. J. Tradit. Complement. Altern. Med. 2013, 10, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babikir, S.A.; Elhassan, G.O.; Hamad-Alneil, A.I.; Alfadl, A.A. Complementary medicine seeking behaviour among infertile women: A Sudanese study. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2021, 42, 101264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekele, G.G.; Woyo, T.; Fekene, D.B.; Gonfa, D.N.; Moti, B.E.; Roga, E.Y.; Yami, A.T.; Bacha, A.J.; Kabale, W.D. Concomitant use of medicinal plants and pharmaceutical drugs among pregnant women in southern Ethiopia. Heliyon 2023, 9, e14805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitessa, D.A.; Bacha, K.; Tola, Y.B.; Murimi, M.; Smith, E.; Gershe, S. Nutritional compositions and bioactive compounds of “Shameta”, A traditional home made fermented porridge provided exclusively to lactating mothers in the western part of Ethiopia. Heliyon 2022, 8, e08990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukong, K.E.; Ogunbolude, Y.; Kamdem, J.P. Breast cancer in Africa: Prevalence, treatment options, herbal medicines, and socioeconomic determinants. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2017, 166, 351–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moroole, M.A.; Materechera, S.A.; Mbeng, W.O.; Aremu, A.O. Medicinal plants used for contraception in South Africa: A review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2019, 235, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shewamene, Z.; Dune, T.; Smith, C. The use of traditional medicine in maternity care among African women in Africa and the diaspora: A systematic review. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 17, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shewamene, Z.; Dune, T.; Smith, C. Use of traditional and complementary medicine for maternal health and wellbeing by African migrant women in Australia: A mixed method study. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2020, 20, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ntoimo, L.C.; Okonofua, F.E.; Ekwo, C.; Solanke, T.O.; Igboin, B.; Imongan, W.; Yaya, S. Why women utilize traditional rather than skilled birth attendants for maternity care in rural Nigeria: Implications for policies and programs. Midwifery 2022, 104, 103158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, L.A.; Soldera, J.C.; Emim, J.A.; Godinho, R.O.; Souccar, C.; Lapa, A.J. Pharmacological screening of Ageratum conyzoides L. (mentrasto). Memórias Do Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 1991, 86, 145–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duke, J.A. Handbook of Medicinal Herbs; CRC press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Pharmacopoeia, A. The Organisation of African Unity’s Scientific Technical and Research Commission, 1st ed.; The Organisation of African Unity’s Scientific Technical and Research Commission: Lagos, Nigeria, 1985; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Mutambwa, M. Représentations populaires de la maladie. In Le Profil Sanitaire du Lushois; Sakatolo, K., Ed.; UNILU: Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Karou, D.; Dicko, M.H.; Sanon, S.; Simpore, J.; Traore, A.S. Antimalarial activity of sida acuta burm. F.(Malvaceae) and pterocarpus erinaceus poir.(Fabaceae). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2003, 89, 291–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schatzman, L.; Strauss, A. Field Research: Strategies for a Natural Sociology; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliff, NJ, USA, 1973; p. 149. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, L.M.; Metzger, J. Medicinal Plants of East and Southeast Asia: Attributed Properties and Uses; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Robineau, L. Hacia una Farmacopea Caribeia; Enda-Caribe y Universidad National Autonoma de Honduras: Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Standley, P.C.; Steyermark, J.A. Flora of Guatemala. Fieldiana: Botany; Natur. Hist. Mus.: Chicago, IL, USA, 1946; p. 493. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S.K.; Yadav, R.; Singh, D.; Singh, A. Toxic effect of two common Euphorbiales latices on the freshwater snail Lymnaea acuminata. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2004, 15, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldé, M.A. Biological and Phytochemical Investigations on Three Plants Widely Used in GUINEAN Traditional Medicine; Universitaire Instelling Antwerpen (Belgium): Antwerp, Belgium, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Galvez, J.; Zarzuelo, A.; Crespo, M.; Lorente, M.; Ocete, M.; Jimenez, J. Antidiarrhoeic activity of Euphorbia hirta extract and isolation of an active flavonoid constituent. Planta Med. 1993, 59, 333–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apitz-Castro, R.; Escalante, J.; Vargas, R.; Jain, M.K. Ajoene, the antiplatelet principle of garlic, synergistically potentiates the antiaggregatory action of prostacyclin, forskolin, indomethacin and dypiridamole on human platelets. Thromb. Res. 1986, 42, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronquillo, F.; Melgar, M.; Carrillo, J.; Martínez, A. Especies Vegetales de Uso Actual y Potencial en Alimentación y Medicina de las Zonas Semiáridas del Nororiente de Guatemala; Cuadernos DIGI: Guatemala City, Guatemala, 1988; p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Illamola, S.M.; Amaeze, O.U.; Krepkova, L.V.; Birnbaum, A.K.; Karanam, A.; Job, K.M.; Bortnikova, V.V.; Sherwin, C.M.; Enioutina, E.Y. Use of herbal medicine by pregnant women: What physicians need to know. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 10, 1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Hwang, J.H.; Hasan, M.A.; Han, D. Herbal medicine use by pregnant women in Bangladesh: A cross-sectional study. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2018, 18, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Reis Altschul, S. Drugs and Foods from Little-Known Plants; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1973; p. 366. [Google Scholar]

- Petit, P. Ménages de Lubumbashi Entre Précarité et Recomposition; L’Harmattan: Paris, France, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Agyare, C.; Asase, A.; Lechtenberg, M.; Niehues, M.; Deters, A.; Hensel, A. An ethnopharmacological survey and in vitro confirmation of ethnopharmacological use of medicinal plants used for wound healing in Bosomtwi-Atwima-Kwanwoma area, Ghana. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2009, 125, 393–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffré, Y.; de Sardan, J.-P.O. Une médecine inhospitalière. Les difficiles relations entre soignants et soignés dans cinq capitales d’Afrique de l’Ouest. In Hommes et Sociétés; APAD; Karthala: Paris, France, 2003; p. 449. [Google Scholar]

- Wome, B. Recherches Ethnopharmacognosiques sur les Plantes Médicinales Utilisées en Médecine Traditionnelle à Kisangani (Haut-Zaïre). Doctoral Thesis, Université libre de Bruxelles, Fac. Sc., Brussels, Belgium, 1985; 561p. [Google Scholar]

- Adjanohoun, E.; Adjakidje, V.; Ahyi, M.; Akpagana, K.; Chibon, P.; El-Hadji, A.; Eyme, J.; Garba, M.; Gassita, J.; Gbeassor, M. Contribution aux Etudes Ethnobotaniques et Floristiques au Togo; From the data bank PHARMEL 2 (ref. HP 10): 1986; Agence de coopération culturelle et technique (ACCT): Paris, France, 1986; p. 671. [Google Scholar]

- Kabangu, K. La Médecine Traditionnelle Africaine; Université d’Indiana; CRP: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1988; Volume 25. [Google Scholar]

- Mbayo, K.M.; Kalonda, M.E.; Tshisand, T.P.; Kisimba, K.E.; Mulamba, M.; Richard, M.K.; Sangwa, K.G.; Mbayo, K.G.; Maseho, M.F.; Bakari, S. Contribution to ethnobotanical knowledge of some Euphorbiaceae used in traditional medicine in Lubumbashi and its surroundings (DRC). J. Adv. Bot. Zool. 2016, 4, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Mensah, A.; Houghton, P.; Fleischer, T.; Adu, C.; Agyare, C.; Ameade, A. Antimicrobial and antioxidant properties of two Ghanaian plants used traditionally for wound healing. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2003, 55, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Fakae, B.; Campbell, A.; Barrett, J.; Scott, I.; Teesdale-Spittle, P.; Liebau, E.; Brophy, P. Inhibition of glutathione S-transferases (GSTs) from parasitic nematodes by extracts from traditional Nigerian medicinal plants. Phytother. Res. 2000, 14, 630–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burkill, H.M. The useful plants of west tropical Africa. In Families EI; Royal Botanic Gardens: Kew, UK, 1994; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Irvine, F.R. Woody Plants of Ghana; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Chukwujekwu, J.C.; Van Staden, J.; Smith, P.; Meyer, J. Antibacterial, anti-inflammatory and antimalarial activities of some Nigerian medicinal plants. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2005, 71, 316–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tona, L.; Cimanga, R.; Mesia, K.; Musuamba, C.; De Bruyne, T.; Apers, S.; Hernans, N.; Van Miert, S.; Pieters, L.; Totté, J. In vitro antiplasmodial activity of extracts and fractions from seven medicinal plants used in the Democratic Republic of Congo. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2004, 93, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samy, R.P.; Ignacimuthu, S. Antibacterial activity of some folklore medicinal plants used by tribals in Western Ghats of India. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2000, 69, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soukup, J. Vocabulary of the Common Names of the Peruvian Flora and Catalog of the Genera; Editorial Salesiano: Lima, Perú, 1970; Volume 436. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter, R.A. Catálogo de Plantas Utiles de la Amazonia Peruana. 1990. Available online: http://repositorio.cultura.gob.pe/handle/CULTURA/645 (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Coimbra, R. Manual de Fitoterapia, 2nd ed.; Editora Cejup: Belem, Brazil, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ayensu, E.S. Medicinal Plants of the West Indies; Reference Publications, Inc.: Algonic, MI, USA, 1981. Available online: https://www.biblio.com/9780917256127 (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Kabiruddin, M. Makhzanul Advia Shaikh Mohd; Bashir and Sons, Lucknow: Lucknow, India, 1951; pp. 454–455. [Google Scholar]

- Kirthikar, K.R.; Basu, B.D.; An, I.C.S. Indian Medicinal Plants; Lalit Mohan Basu: Allahabad, India, 1969; Available online: http://asi.nic.in/asi_books/2047.pdf (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Telefo, P.; Lienou, L.; Yemele, M.; Lemfack, M.; Mouokeu, C.; Goka, C.; Tagne, S.; Moundipa, F. Ethnopharmacological survey of plants used for the treatment of female infertility in Baham, Cameroon. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011, 136, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraf, S.; Dixit, V.K.; Tripathi, S.C.; Patnaik, G.K. Antihepatotoxic activity of Cassia occidentalis. Int. J. Pharmacogn. 1994, 32, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, S.C.; Chen, S.C.; La, C.F.; Teng, C.M.; Wang, J.P. Studies on the anti-inflammatory and antiplatelet activities of constituents isolated from the roots and stem of Cassia occidentalis L. Chin. Pharm. J. 1996, 48, 291–302. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, L. Ethnomedical Uses of Plants in Nigeria; Uniben Press: Benin City, Nigeria, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Pool, R. Dialogue and the Interpretation of Illness. In Conversations in a Cameroon Village; Oxford et Providence: Heidelberg, Germany; Oxford, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Lockett, C.; Calvert, C.C.; Louis, E.; Grivetti, L. Energy and micronutrient composition of dietary and medicinal wild plants consumed during drought. Study of rural Fulani, Northeastern Nigeria. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2000, 51, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambeze, K.S. Le Profil Sanitaire du Lushois, Rapport de Recherches Effectuées Durant la Troisième Session des Travaux de l’Observatoire de Changement Urbain en Février-Juin 2001; Université de Lubumbashi, UNILU: Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Odeleye, O.M. Comparative Pharmacognostical Studies on Aloe Schweinfurthii Baker and Aloe vera (Linn.) Burm; Obafemi Awolowo University: Ile-Ife, Nigeria, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Delaude, C.; Breyne, M. Plantes Médicinales et Ingrédients Magiques du Grand Marché de Kinshasa. Africa-Tervuren, n 17 1971. Available online: http://nzenzeflowerspauwels.be/Plantes_Medicinales_du_Zaire.pdf (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Tabuti, J.; Lye, K.; Dhillion, S. Traditional herbal drugs of Bulamogi, Uganda: Plants, use and administration. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2003, 88, 19–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apitz-Castro, R.; Badimon, J.J.; Badimon, L. Effect of ajoene, the major antiplatelet compound from garlic, on platelet thrombus formation. Thromb. Res. 1992, 68, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochwang’i, D.O.; Kimwele, C.N.; Oduma, J.A.; Gathumbi, P.K.; Mbaria, J.M.; Kiama, S. Medicinal plants used in treatment and management of cancer in Kakamega County, Kenya. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 151, 1040–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noumi, E.; Tchakonang, N. Plants used as abortifacients in the Sangmelima region of Southern Cameroon. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2001, 76, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quiroz, D.; Towns, A.; Legba, S.I.; Swier, J.; Brière, S.; Sosef, M.; van Andel, T. Quantifying the domestic market in herbal medicine in Benin, West Africa. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 151, 1100–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, S.; Yeung, H.; Leung, K. The immunosuppressive activities of two abortifacient proteins isolated from the seeds of bitter melon (Momordica charantia). Immunopharmacology 1987, 13, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolajsen, T.; Nielsen, F.; Rasch, V.; Sørensen, P.H.; Ismail, F.; Kristiansen, U.; Jäger, A.K. Uterine contraction induced by Tanzanian plants used to induce abortion. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011, 137, 921–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehane, K.L. Abortion in the north of Burkina Faso. Afr. J. Reprod. Health 1999, 3, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, B.; Soelberg, J.; Kristiansen, U.; Jäger, A. Uterine contraction induced by Ghanaian plants used to induce abortion. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2016, 106, 137–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calder, B.L.; Brown, Y.M.; Rae, D.I. Female circumcision/genital mutilation: Culturally sensitive care. Health Care Women Int. 1993, 14, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouba, L.J.; Muasher, J. Female circumcision in Africa: An overview. Afr. Stud. Rev. 1985, 28, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birge, Ö.; Serin, A.N. The relationship between female circumcision and the religion. In Circumcision and the Community; IntechOpen Limited: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyangweso, M. Christ’s salvific message and the Nandi ritual of female circumcision. Theol. Stud. 2002, 63, 579–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergiat, A.-M. Plantes magiques et médicinales des Féticheurs de l’Oubangui (Région de Bangui) (suite). J. Agric. Trad. Bot. Appl 1970, 17, 60–91. [Google Scholar]

- Olowokere, A.; Olajide, O. Women’s perception of safety and utilization of herbal remedies during pregnancy in a local government area in Nigeria. Clin. Nurs. Stud. 2013, 1, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malan, D.F.; Neuba, D.F. Traditional practices and medicinal plants use during pregnancy by Anyi-Ndenye women (Eastern Côte d’Ivoire). Afr. J. Reprod. Health 2011, 15, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Orief, Y.I.; Farghaly, N.F.; Ibrahim, M.I.A. Use of herbal medicines among pregnant women attending family health centers in Alexandria. Middle East. Fertil. Soc. J. 2014, 19, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanafy, S.A.; Sallam, S.A.; Kharboush, I.F.; Wahdan, I. Drug utilization pattern during pregnancy in Alexandria, Egypt. Eur. J. Pharm. Med. Res. 2016, 3, 19–29. [Google Scholar]

- Kebede, B.; Gedif, T.; Getachew, A. Assessment of drug use among pregnant women in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2009, 18, 462–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyiapat, J.-L.E. Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use Among Pregnant Women in Udi Local Government Area of Enugu State; University of Nigeria: Nsukka, Nigeria, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bayisa, B.; Tatiparthi, R.; Mulisa, E. Use of herbal medicine among pregnant women on antenatal care at Nekemte Hospital, Western Ethiopia. Jundishapur J. Nat. Pharm. Prod. 2014, 9, e17368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekuria, A.B.; Erku, D.A.; Gebresillassie, B.M.; Birru, E.M.; Tizazu, B.; Ahmad, A. Prevalence and associated factors of herbal medicine use among pregnant women on antenatal care follow-up at University of Gondar referral and teaching hospital, Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 17, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adusi-Poku, Y.; Vanotoo, L.; Detoh, E.; Oduro, J.; Nsiah, R.; Natogmah, A. Type of herbal medicines utilized by pregnant women attending ante-natal clinic in Offinso north district: Are orthodox prescribers aware? Afr. J. Reprod. Health 2015, 49, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillary, N.C. Utilization of Herbal Medicine During Pregnancy, Labour and Post-Partum Period Among Women at Embu Provincial General Hospital. Unpublished Thesis. Nairobi University, College of Humanities and Social Science, Sociology: Nairobi, Kenya, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Elkhoudri, N.; Baali, A.; Amor, H. Maternal Morbidity and the Use of Medicinal Herbs in the City of Marrakech, Morocco. Indian J. Tradit. Knowl. 2016, 15, 79–85. [Google Scholar]

- Duru, C.; Nnebue, C.; Uwakwe, K.; Diwe, K.; Agunwa, C.; Achigbu, K.; Iwu, C.; Merenu, I. Prevalence and pattern of herbal medicine use in pregnancy among women attending clinics in a tertiary hospital in Imo State, South East Nigeria. Int. J. Curr. Res. Biosci. Plant. Biol. 2016, 3, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duru, C.B.; Uwakwe, K.A.; Chinomnso, N.C.; Mbachi, I.I.; Diwe, K.C.; Agunwa, C.C.; Iwu, A.C.; Merenu, I.A. Socio-demographic determinants of herbal medicine use in pregnancy among Nigerian women attending clinics in a tertiary Hospital in Imo State, south-east, Nigeria. J. Am. J. Med. Stud. 2016, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Mureyi, D.D.; Monera, T.G.; Maponga, C.C. Prevalence and patterns of prenatal use of traditional medicine among women at selected harare clinics: A cross-sectional study. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2012, 12, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kankara, S.S.; Ibrahim, M.; Mustafa, M.; Go, R. Ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants used for traditional maternal healthcare in Katsina state, Nigeria. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2015, 97, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, P.B.; Taidy-Leigh, L.; Bah, A.J.; Kanu, J.S.; Kangbai, J.B.; Sevalie, S. Prevalence and correlates of herbal medicine use among women seeking Care for Infertility in Freetown, Sierra Leone. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2018, 2018, 9493807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahams, N.; Jewkes, R.; Mvo, Z. Indigenous healing practices and self-medication amongst pregnant women in Cape Town, South Africa. Afr. J. Reprod. Health 2002, 6, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga, C.A.; Veale, D. Isihlambezo: Utilization patterns and potential health effects of pregnancy-related traditional herbal medicine. Soc. Sci. Med. 1997, 44, 911–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabina, M.; Moodley, J.; Pitsoe, S. The use of traditional herbal medication during pregnancy. Trop. Dr. 1997, 27, 84–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watt, J.M.; Breyer-Brandwijk, M.G. The Medicinal and Poisonous Plants of Southern and Eastern Africa Being an Account of Their Medicinal and Other Uses, Chemical Composition, Pharmacological Effects and Toxicology in Man and Animal; E. & S. Livingstone Ltd.: Edinburgh, UK, 1962; pp. 16–17. [Google Scholar]

- Hutching, A. Zulu Medicinal Plants, an Inventory; University of Natal Press: Pietermaritzburg, South Africa, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Deutschländer, M.; Van de Venter, M.; Roux, S.; Louw, J.; Lall, N. Hypoglycaemic activity of four plant extracts traditionally used in South Africa for diabetes. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2009, 124, 619–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabogo, D. The Ethnobotany of the VHA-VENDA. Master’s Thesis, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Rood, B. Uit Die Veldapteek; Tafelberg-Publishers: Cape Town, South Africa, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Mahwasane, S.; Middleton, L.; Boaduo, N. An ethnobotanical survey of indigenous knowledge on medicinal plants used by the traditional healers of the Lwamondo area, Limpopo province, South Africa. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2013, 88, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wyk, B.-E.; Gericke, N. People’s Plants: A Guide to Useful Plants of Southern Africa. Briza Publications: Pretoria, South Africa, 2000; p. 352. [Google Scholar]

- Maritz, K. Gannabossie Is Beter as “Die Pil”; Dagbreek en Landstem: Johannesburg, South Africa, 1969; Volume 23, p. 33. [Google Scholar]

- Mawoza, T.; Nhachi, C.; Magwali, T. Prevalence of traditional medicine use during pregnancy, at labour and for postpartum care in a rural area in Zimbabwe. Clin. Mother. Child. Health 2019, 16, 321, NIHMSID: NIHMS1036101. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Okwuasaba, F.; Osunkwo, U.; Ekwenchi, M.; Ekpenyong, K.; Onwukeme, K.; Olayinka, A.; Uguru, M.; Das, S. Anticonceptive and estrogenic effects of a seed extract of Ricinus communis var. minor. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1991, 34, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okwuasaba, F.; Das, S.; Isichei, C.; Ekwenchi, M.; Onoruvwe, O.; Olayinka, A.; Uguru, V.; Dafur, S.; Ekwere, E.; Parry, O. Pharmacological studies on the antifertility effects of RICOM-1013-J from Ricinus communis var minor and preliminary clinical studies on women volunteers. Phytother. Res. Int. J. Devoted Med. Sci. Res. Plants Plant Prod. 1997, 11, 547–551. [Google Scholar]

- Nath, S.; Kadasi, A.; Grossmann, R.; Sirotkin, A.; Kolesarova, A.; Talukdar, A.; Choudhury, M. Ricinus communis L. stem bark extracts regulate ovarian cell functions and secretory activity and their response to Luteinising hormone. Int. J. Impot. Res. 2015, 27, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iornmube, U.J.; Ekwere, E.O.; McNeil, R.T.; Francis, O.K. The Mechanism of Action and Effect on the Cervix of the Seed of Ricinus communis Var. Minor (RICOM-1013-J) in Women Volunteers in Nigeria. J. Nat. Sci. 2016, 6, 64–70. [Google Scholar]

- Sanni, A.C.; Moritiwon, O.; Ogundeko, T.O.; Ramyil, S.M.C.; Bassi, P.A.; Okwuasaba, F.K. Antifertility Efficacy of n-Hexane Seed Extract of Ricinus communis Var Minor in Wistar Rats Uterus In Vitro. Path Sci. 2024, 10, 8001–8009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salami, S.A.; Raji, Y. Oral Ricinus communis oil exposure at different stages of pregnancy impaired hormonal, lipid profile and histopathology of reproductive organs in Wistar rats. J. Med. Plant Res. 2014, 18, 1289–1298. [Google Scholar]

- Majumder, M.; Debnath, S.; Gajbhiye, R.L.; Saikia, R.; Gogoi, B.; Samanta, S.K.; Das, D.K.; Biswas, K.; Jaisankar, P.; Mukhopadhyay, R. Ricinus communis L. fruit extract inhibits migration/invasion, induces apoptosis in breast cancer cells and arrests tumor progression in vivo. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 14493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, F.; Khalilzadeh, S.; Nejatbakhsh, F. Therapeutic effects of garlic (Allium sativum) on female reproductive system: A systematic review. Heliyon 2023, 9, e22555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongiorno, P.B.; Fratellone, P.M.; LoGiudice, P. Potential health benefits of garlic (Allium sativum): A narrative review. J. Complement. Integr. Med. 2008, 5, 1–24. Available online: http://www.bepress.com/jcim/vol5/iss1/1 (accessed on 8 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Barnes, J. Pharmacovigilance for Herbal and Traditional Medicines; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astuti, L.P.; Amelia, P.F.; Wijayanti, H. Application of the WBZ (Warm Belt Zinger) Method to the Intensity of Labor Pain at the BL 31-32 Meridian Points in PMB Semarang City. Health Notions 2020, 4, 375–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrisnijati, D.; Wiboworini, B.; Sugiarto, S. Effects of Pineapple Juice and Ginger Drink for Relieving Primary Dysmenorrhea Pain among Adolescents. Indones. J. Med. 2019, 4, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace, I.; Anyanwu, C.F.; Obinna, V.C. Oestrogenic Activity of Aqueous Ethanol Extract of Cucurbita pepo (Pumpkin) Seed in Female Wistar Rats. Asian J. Res. Rep. Endocrinol. 2023, 6, 170–178. [Google Scholar]

- Lestari, B.; Meiyanto, E. A review: The emerging nutraceutical potential of pumpkin seeds. Indones. J. Cancer Chemoprevention 2018, 9, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.; Hong, S.; Ko, S.-H.; Kim, H.-S. Evaluation of Antioxidant Effects of Pumpkin (Cucurbita pepo L.) Seed Extract on Aging-and Menopause-Related Diseases Using Saos-2 Cells and Ovariectomized Rats. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traore, O.; Ouedraogo, A.; Compaore, M.; Nikiema, K.; Zombre, A.; Kiendrebeogo, M.; Blankert, B.; Duez, P. Social perceptions of malaria and diagnostic-driven malaria treatment in Burkina Faso. Heliyon 2021, 7, e05553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahumba, J.; Rasamiravaka, T.; Okusa Ndjolo, P.; Bakari, S.A.; Bizumukama, L.; Kiendrebeogo, M.; El Jaziri, M.; Williamson, E.; Duez, P. Traditional African medicine: From ancestral knowledge to a modern integrated future. Science 2015, 350, S61–S63. [Google Scholar]

- Okaiyeto, K.; Oguntibeju, O.O. African herbal medicines: Adverse effects and cytotoxic potentials with different therapeutic applications. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, E.; Chan, K.; Xu, Q.; Nachtergael, A.; Bunel, V.; Zhang, L.; Ouedraogo, M.; Nortier, J.; Qu, F.; Shaw, D. Integrated toxicological approaches to evaluating the safety of herbal medicine. Science 2015, 347, S47–S49. [Google Scholar]

- Steenkamp, V. Traditional herbal remedies used by South African women for gynaecological complaints. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2003, 86, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, L.O.; Simoes, R.S.; de Jesus Simoes, M.; Girão, M.J.B.C.; Grundmann, O. Pregnancy and herbal medicines: An unnecessary risk for women’s health—A narrative review. Phytother. Res. 2018, 32, 796–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouedraogo, M.; Baudoux, T.; Stévigny, C.; Nortier, J.; Colet, J.-M.; Efferth, T.; Qu, F.; Zhou, J.; Chan, K.; Shaw, D. Review of current and “omics” methods for assessing the toxicity (genotoxicity, teratogenicity and nephrotoxicity) of herbal medicines and mushrooms. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012, 140, 492–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamel, N.; El Boullani, R.; Cherrah, Y. Use of Medicinal Plants during Pregnancy, Childbirth and Postpartum in Southern Morocco. Healthcare 2022, 10, 2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevrin, T.; Boquien, C.-Y.; Gandon, A.; Grit, I.; de Coppet, P.; Darmaun, D.; Alexandre-Gouabau, M.-C. Fenugreek stimulates the expression of genes involved in milk synthesis and milk flow through modulation of insulin/GH/IGF-1 axis and oxytocin secretion. Genes 2020, 11, 1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bournine, L.; Bensalem, S.; Fatmi, S.; Bedjou, F.; Mathieu, V.; Iguer-Ouada, M.; Kiss, R.; Duez, P. Evaluation of the cytotoxic and cytostatic activities of alkaloid extracts from different parts of Peganum harmala L.(Zygophyllaceae). Eur. J. Integr. Med. 2017, 9, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achour, S.; Saadi, H.; Turcant, A.; Banani, A.; Mokhtari, A.; Soulaymani, A. Peganum harmala L. poisoning and pregnancy: Two cases in Morocco. Med. Sante Trop. 2012, 22, 84–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamoudi, M.K.; Almehmadi, K.A.; Ali, M.S.; Hashmi, S. Ethnopharmacological Study on Nigella Sativa Seeds Extracts: Pharmacognostical Screening, Abortifacient Potential and its Evolution Parameters. Migr. Lett. 2023, 20, 765–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbuKhader, M.M.; Khater, S.H.; Al-Matubsi, H.Y. Acute effects of thymoquinone on the pregnant rat and embryo-fetal development. Drug Chem. Toxicol. 2013, 36, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemonica, I.; Damasceno, D.; Di-Stasi, L. Study of the embryotoxic effects of an extract of rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.). Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 1996, 29, 223–227. [Google Scholar]

- Sá, R.C.S.; Leite, M.N.; Oliveira, L.E.; Toledo, M.M.; Greggio, T.C.; Guerra, M.O. Preliminary assessment of Rosmarinus officinalis toxicity on male Wistar rats’ organs and reproductive system. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 2006, 16, 324–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souhila, T.; Fatma Zohra, B.; Tahar, H.S. Identification and quantification of phenolic compounds of Artemisia herba-alba at three harvest time by HPLC–ESI–Q-TOF–MS. Int. J. Food Prop. 2019, 22, 843–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laadraoui, J.; Aboufatima, R.; El Gabbas, Z.; Ferehan, H.; Bezza, K.; Laaradia, M.A.; Marhoume, F.; Wakrim, E.M.; Chait, A. Effect of Artemisia herba-alba consumption during pregnancy on fertility, morphological and behaviors of mice offspring. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 226, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernstein, N.; Akram, M.; Yaniv-Bachrach, Z.; Daniyal, M. Is it safe to consume traditional medicinal plants during pregnancy? Phytother. Res. 2021, 35, 1908–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, N.; Nath, D.; Singh, R. Teratological Aspects of Abrus Precatorius Seeds in Rats; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 1990; ISSN 0367-326X. cabidigitallibrary.org. CABI Record Number: 19900360321. [Google Scholar]

- Shibeshi, W.; Makonnen, E.; Zerihun, L.; Debella, A. Effect of Achyranthes aspera L. on fetal abortion, uterine and pituitary weights, serum lipids and hormones. Afr. Health Sci. 2006, 6, 108–112. [Google Scholar]

- Cuzzolin, L.; Francini-Pesenti, F.; Verlato, G.; Joppi, M.; Baldelli, P.; Benoni, G. Use of herbal products among 392 Italian pregnant women: Focus on pregnancy outcome. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2010, 19, 1151–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, L.; Cohen, M. Herbs and Natural Supplements-an Evidence-Based Guide; Elselvier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha, J.; Shanbhag, T.; Shenoy, S.; Amuthan, A.; Prabhu, K.; Sharma, S.; Banerjee, S.; Kafle, S. Antiovulatory and abortifacient effects of Areca catechu (betel nut) in female rats. Indian J. Pharmacol. 2010, 42, 306–311. [Google Scholar]

- Samavati, R.; Ducza, E.; Hajagos-Tóth, J.; Gaspar, R. Herbal laxatives and antiemetics in pregnancy. Reprod. Toxicol. 2017, 72, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, F.; Johnson, C. Complementary and alternative medicine in obstetrics. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2005, 91, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, N.; Nath, D.; Shukla, S.; Dyal, R. Abortifacient activity of a medicinal plant “Moringa oleifera” in rats. Anc. Sci. Life 1988, 7, 172–174. [Google Scholar]

- Namulindwa, A.; Nkwangu, D.; Oloro, J. Determination of the abortifacient activity of the aqueous extract of Phytolacca dodecandra (LHer) leaf in Wistar rats. Afr. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2015, 9, 43–47. [Google Scholar]

- Dabhadkar, D.; Zade, V. Abortifacient activity of Plumeria rubra (Linn) pod extract in female albino rats. Indian J. Exp. Biol. 2012, 50, 702–707. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- O’Sullivan, M.D.; Hehir, M.P.; O’Brien, Y.M.; Morrison, J.J. 17 alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate vehicle, castor oil, enhances the contractile effect of oxytocin in human myometrium in pregnancy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 202, 453.e1–453.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Pajares, J.L.; Zúñiga, L.; Pino, J. Ruta graveolens aqueous extract retards mouse preimplantation embryo development. Reprod. Toxicol. 2003, 17, 667–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakubu, M.T.; Bukoye, B.B. Abortifacient potentials of the aqueous extract of Bambusa vulgaris leaves in pregnant Dutch rabbits. Contraception 2009, 80, 308–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golub, M.S.; Takeuchi, P.T.; Keen, C.L.; Hendrickx, A.G.; Gershwin, M.E. Activity and attention in zinc-deprived adolescent monkeys. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1996, 64, 908–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niroumand, M.C.; Heydarpour, F.; Farzaei, M.H. Pharmacological and therapeutic effects of Vitex agnus-castus L.: A review. Pharmacogn. Rev. 2018, 12, 103–114. [Google Scholar]

- Dog, T.L.; Marles, R.; Mahady, G.; Gardiner, P.; Ko, R.; Barnes, J.; Chavez, M.L.; Griffiths, J.; Giancaspro, G.; Sarma, N.D. Assessing safety of herbal products for menopausal complaints: An international perspective. Maturitas 2010, 66, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masullo, M.; Montoro, P.; Mari, A.; Pizza, C.; Piacente, S. Medicinal plants in the treatment of women’s disorders: Analytical strategies to assure quality, safety and efficacy. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2015, 113, 189–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, S. Safety and Pharmacovigilance of Herbal Medicines in Pregnancy. In Pharmacovigilance for Herbal and Traditional Medicines: Advances, Challenges and International Perspectives; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 77–91. [Google Scholar]

- Kargozar, R.; Azizi, H.; Salari, R. A review of effective herbal medicines in controlling menopausal symptoms. Electron. Physician 2017, 9, 5826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verpoorte, R. Good practices: The basis for evidence-based medicines. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012, 140, 455–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Shaw, D.; Graeme, L.; Pierre, D.; Elizabeth, W.; Kelvin, C. Pharmacovigilance of herbal medicine. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012, 140, 513–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Yan, J.; Liu, X.; Ye, Z.; Yang, X.; Meyboom, R.; Chan, K.; Shaw, D.; Duez, P. Pharmacovigilance practice and risk control of Traditional Chinese Medicine drugs in China: Current status and future perspective. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012, 140, 519–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiguba, R.; Olsson, S.; Waitt, C. Pharmacovigilance in low-and middle-income countries: A review with particular focus on Africa. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2023, 89, 491–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Global Report on Traditional and Complementary Medicine 2019; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Guedje, N.M.; Tadjouteu, F.; Dongmo, R.F. Médecine traditionnelle africaine (MTR) et phytomédicaments: Défis et stratégies de développement. Health Sci. Dis. 2012, 13, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Mati, F.G.; Vidjro, S.W.; Ouoba, K.; Amonkou, A.C.; Trapsida, J.-M.; Amari, S.A.; Pabst, J.-Y. La pratique de la médecine et pharmacopée traditionnelles au Niger: Concilier le savoir ancestral aux exigences de la règlementation pharmaceutique. J. Afr. Technol. Pharm. Biopharmacie 2022, 1, 16–26. [Google Scholar]

- Dzoyem, J.P.; Tshikalange, E.; Kuete, V. Medicinal plants market and industry in Africa. In Medicinal Plant Research in Africa; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 859–890. [Google Scholar]

- Mutombo, C.S.; Bakari, S.A.; Ntabaza, V.N.; Nachtergael, A.; Lumbu, J.-B.S.; Duez, P.; Kahumba, J.B. Perceptions and use of traditional African medicine in Lubumbashi, Haut-Katanga province (DR Congo): A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0276325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| County or Region | Used Remedy | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Burkina Faso | An infusion of daaga (Kalanchoe pinnata (Lam.) Pers.) and kalakoe (Ageratum conyzoides Sieber ex Steud.). | [32] |

| Gabon and the Central African Republic | An infusion of papaya (Carica papaya L.), parsley (Petroselinum crispum (Mill.) Nyman ex A. W. Hill), and lemon (Citrus limon (L.) Osbeck). | [33] |

| Côte d’Ivoire and Benin | Caraway (Carum carvi L.), yarrow (Achillea millefolium L.), white willow (Salix alba L.), and peony (Paeonia officinalis L.). | [34] |

| Maghreb | Infusions of Verbena officinalis L., valerian (Valeriana officinalis L.), and rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) to relieve premenstrual syndromes. | [34] |

| Mali | Boiled foléré (Hibiscus sabdariffa L.), massep (Ocimum gratissimum L.), and parsley (Petroselinum crispum (Mill.) Nyman ex A. W. Hill) for irregular menstruation | [34] |

| Côte d’Ivoire | Aloe vera (L.) Burm.f. gel applied to the intimate area by women to treat infections. | [34] |

| Cameroon | Cinnamon infusion (Cinnamomum verum J. Presl) applied to the intimate area by women in case of infection. | [34] |

| Democtratic republic of the Congo | Papaya leaves (Carica papaya L.) and sombe (Manihot esculenta Crantz). | [35] |

| Burkina Faso, Guinea, Mali, and Nigeria | Infusion of Senegal rosewood (Pterocarpus erinaceus Poir.). | [36] |

| South Africa | Motherwort (Leonurus cardiaca L.) for irregular menstruation. | [37] |

| South Africa | Yarrow infusion (Achillea millefolium L.) for intimate hygiene problems. | [37] |

| Angola | Zimbabwe raspberry (Rubus idaeus L.) leaves for irregular menstruation. | [38] |

| Maghreb | Heavy periods are treated with a decoction of Ligusticum wallichii Franch. (a synonym of Ligusticum striatum DC.), peony (Paeonia officinalis L.), and nettle (Urtica dioica L.). | [39,40] |

| Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Guinea Bissau, Guinea, Nigeria, and Sierra Leone | The root of pea cane (Phyllanthus niruri var genuinus Mull Arg, synonym of Phyllanthus amarus Schumach. & Thonn.) is infused during heavy periods. | [41] |

| Sub-Saharan Africa, such as Gabon, Benin, and Côte d’Ivoire | The application of fintinko (Harrisonia abyssinica Oliv.) leaves with seeds, kaolin, and salt for intimate hygiene problems. | [42] |

| Sub-Saharan Africa, such as Gabon, Benin, and Côte d’Ivoire | Decoction and infusion of wal-biisem (Euphorbia hirta L.); yulin-gnuuga (Ocimum gratissimum L.); kultãnga (Cassia alata L., synonym of Senna alata (L.) Roxb.); goya (Psidium guajava L.); nekiljem (Holarrhena floribunda T. Durand and Schinz); rõbré (Ageratum conyzoides Sieber ex Steud.); and imbuur (Citrus aurantifolia (Christm.) Swingle) for intimate hygiene problems. | [43] |

| Senegal and Ghana | Parsley (Petroselinum crispum (Mill.) Nyman ex A. W. Hill) and garlic (Allium sativum L.) for intimate hygiene problems. | [44] |

| Plant Name | Adverse Effects | References |

|---|---|---|

| Rosary pea (Abrus precatorius L.) | May induce abortion. | [153] |

| Chaff-flower (Achyranthes aspera L.) | Abortifacient activity in rats. | [154] |

| Aloe vera (Aloe barbadensis miller) | Latex may cause stimulation of uterus contraction and abortion. | [155] |

| Garlic (Allium sativum L.) | Excessive consumption may augment the threat of pregnancy loss, uterine contraction, and hemorrhage. | [156] |

| Betel-nut palm (Areca catechu (Linn)) | Induced abortion. | [157] |

| Coffee senna (Cassia occidentalis L.) | High dose induced tissue damage in the mother and myocardium bone necrosis. | [158] |

| Chamomile (Chamaemelum nobile (L.) All.) | It is a stimulant of uterine contraction care. | [159] |

| Drumstick tree (Moringa oleifera) | Has abortifacient activity in albino rats. | [160] |

| Gopo berry (Phytolacca dodecandra L.) | Abortifacient activity. | [161] |

| Red paucipan (Plumeria rubra L.) | Reduced fetuses lives and induced labor. | [162] |

| Ricinus communis L. (Euphorbiaceae) | It can stimulate the passage of meconium and results in neonatal respiratory distress aspiration. | [163] |

| Rue (Ruta graveolens Linn.) | Stimulates uterus motility, abortion, and induces abnormal embryos. | [164] |

| Candle bush (Senna alata L.) | Abortifacient activity. | [165] |

| Fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum L.) | Teratogenic effects, and seed consumption during pregnancy has been associated with a range of congenital malformations. | [158] |

| Valerian (Valeriana officinalis L.) | Its consumption at the second trimester of pregnancy can cause zinc deficiency in the fetus. | [166] |

| Chaste tree (Vitus agnus-castus L. (VAC) | Induces ovarian hyperstimulation and may enhance the threat of miscarriage. | [167] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brahmi, F.; Kampemba Mujinga, F.; Guendouze, N.; Madani, K.; Boulekbache, L.; Duez, P. Benefits of Traditional Medicinal Plants to African Women’s Health: An Overview of the Literature. Diseases 2025, 13, 160. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases13050160

Brahmi F, Kampemba Mujinga F, Guendouze N, Madani K, Boulekbache L, Duez P. Benefits of Traditional Medicinal Plants to African Women’s Health: An Overview of the Literature. Diseases. 2025; 13(5):160. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases13050160

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrahmi, Fatiha, Florence Kampemba Mujinga, Naima Guendouze, Khodir Madani, Lila Boulekbache, and Pierre Duez. 2025. "Benefits of Traditional Medicinal Plants to African Women’s Health: An Overview of the Literature" Diseases 13, no. 5: 160. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases13050160

APA StyleBrahmi, F., Kampemba Mujinga, F., Guendouze, N., Madani, K., Boulekbache, L., & Duez, P. (2025). Benefits of Traditional Medicinal Plants to African Women’s Health: An Overview of the Literature. Diseases, 13(5), 160. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases13050160