Negative Outcomes of Blepharoplasty and Thyroid Disorders: Is Compensation Always Due? A Case Report with a Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

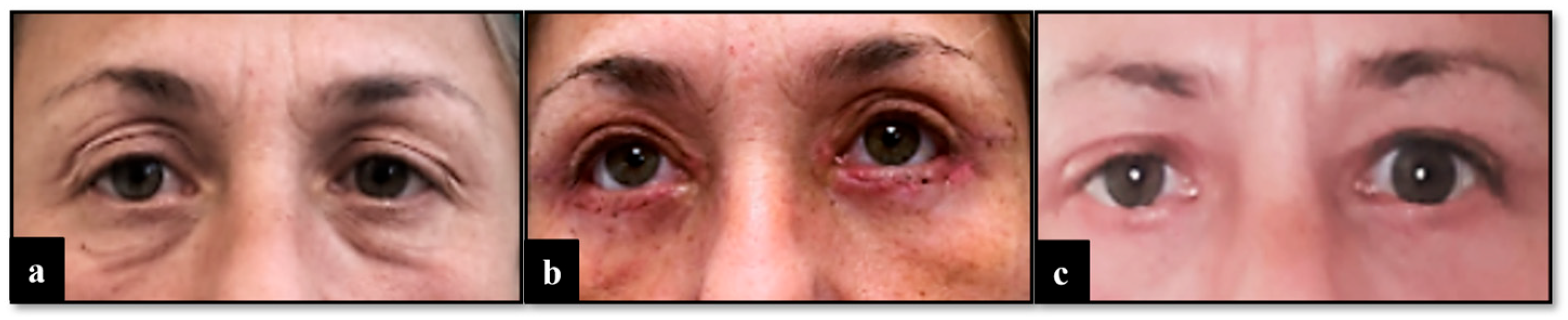

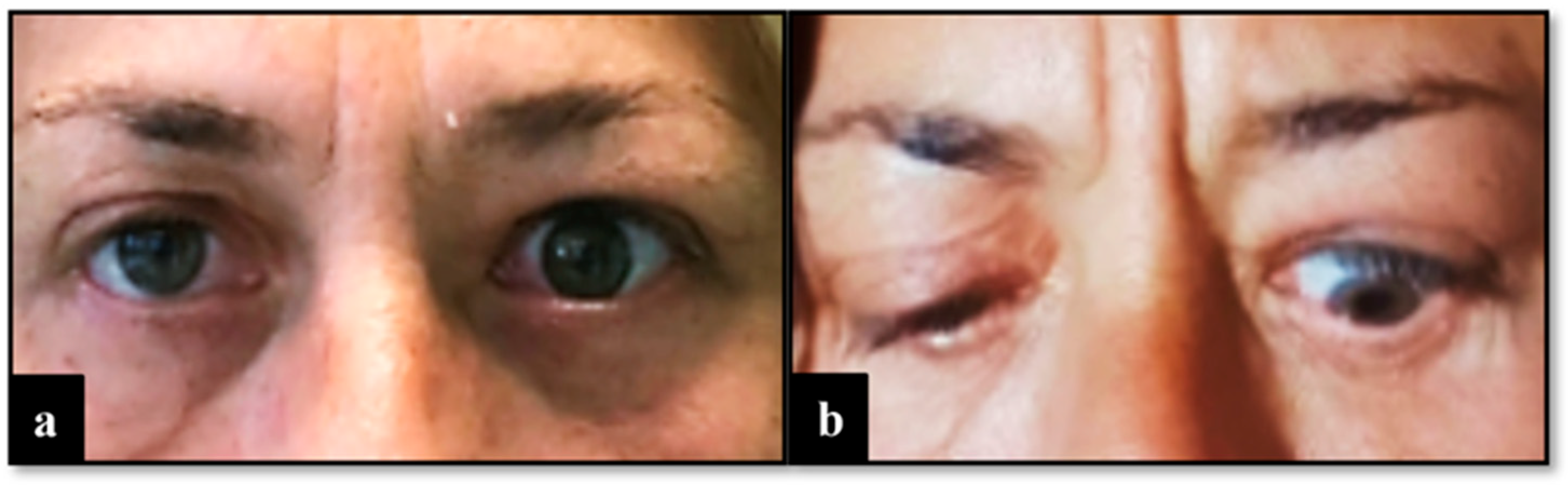

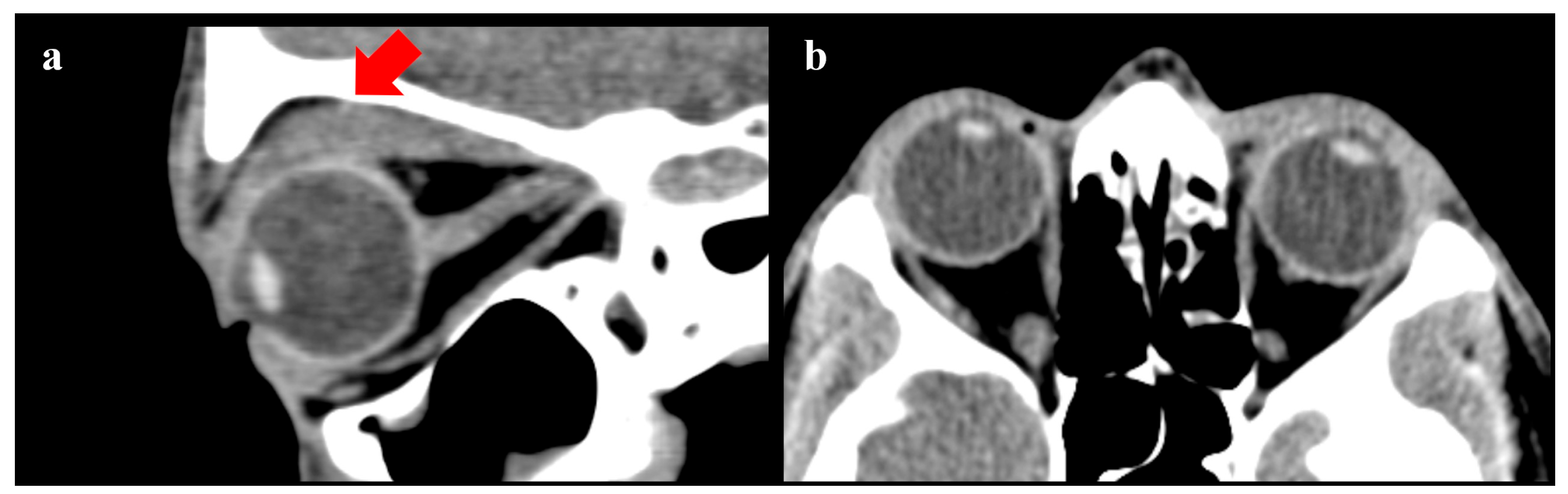

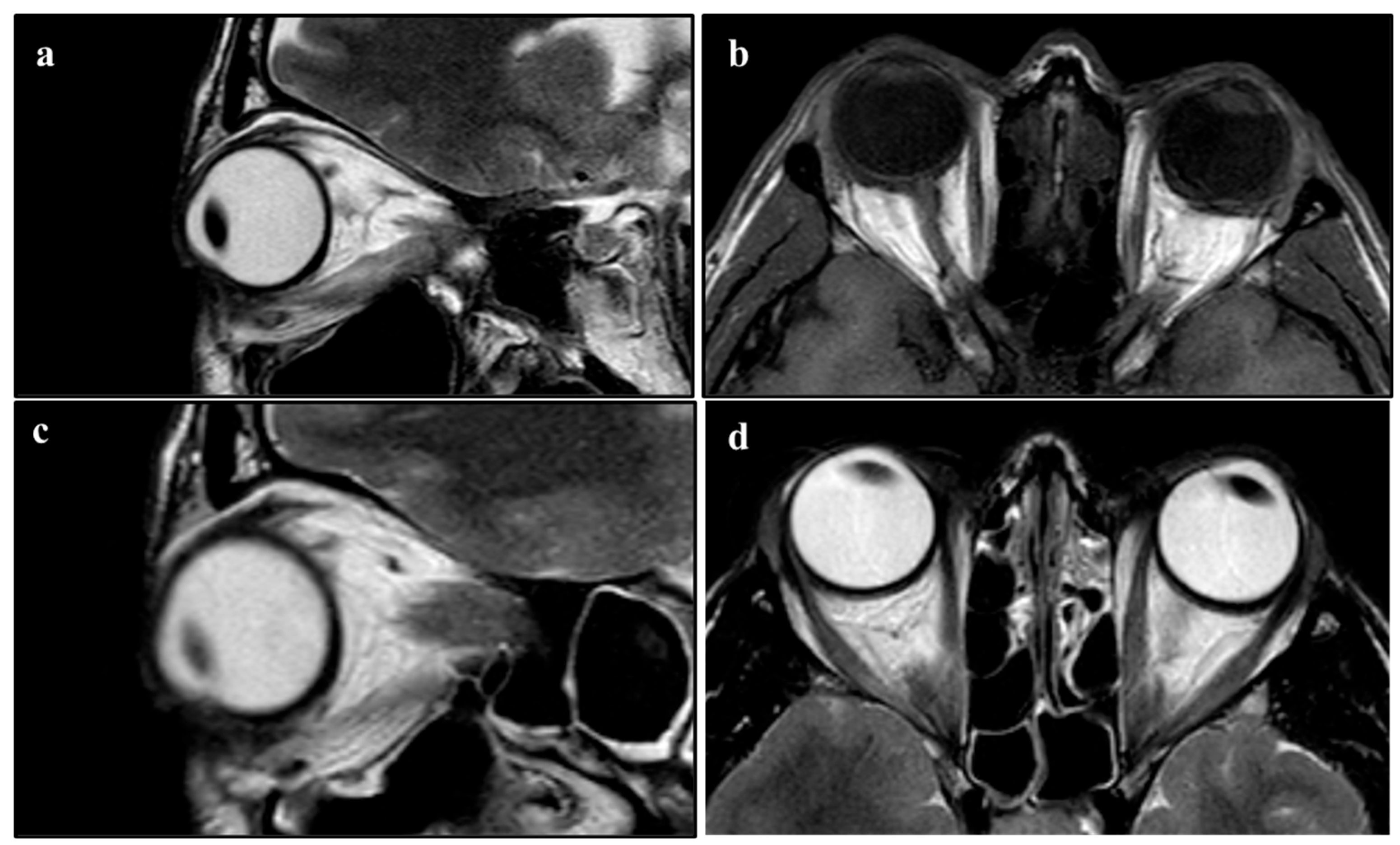

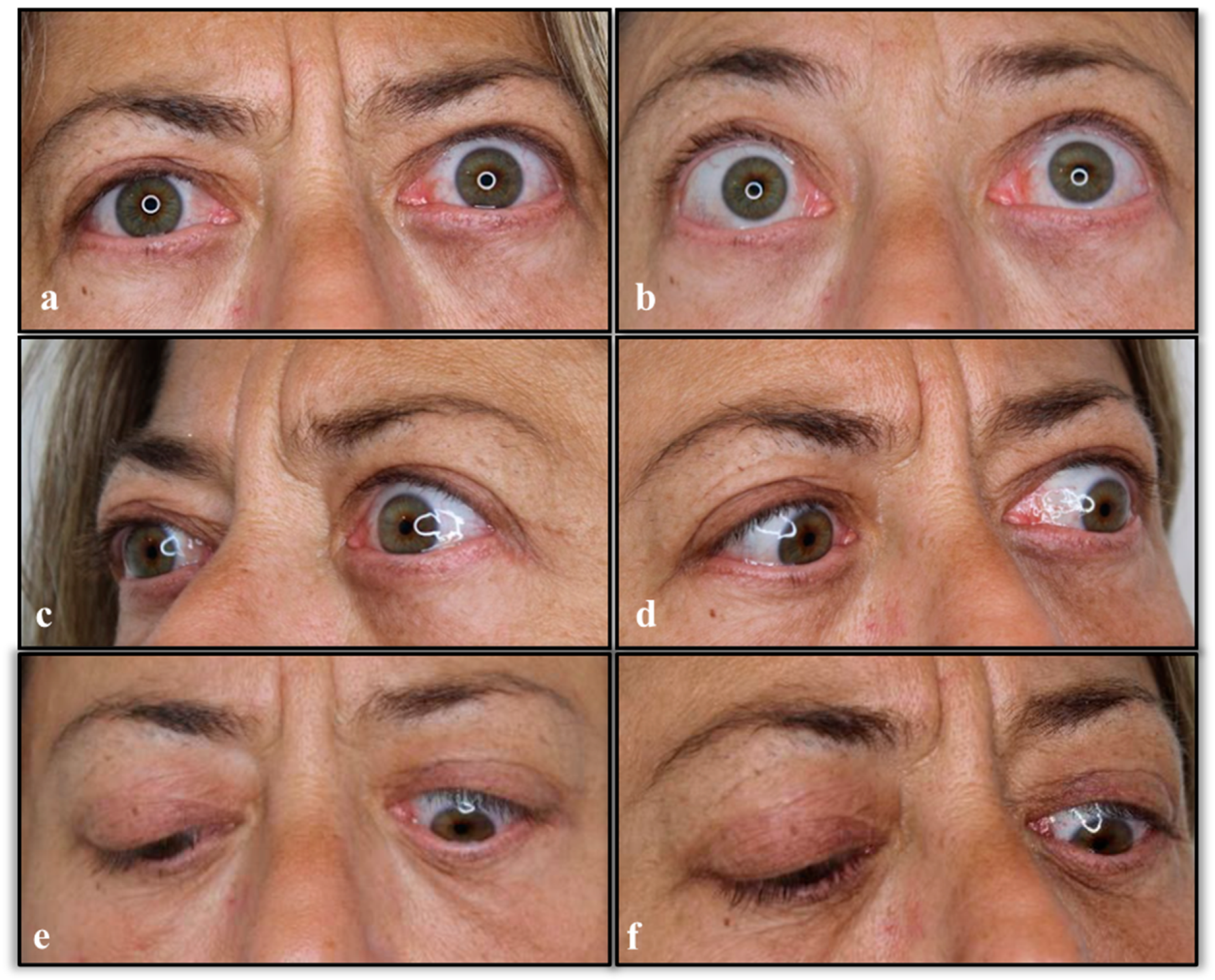

2. Case Description

3. Literature Review Methodology

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS). 2022 Plastic Surgery Statistics. Available online: https://www.plasticsurgery.org/news/plastic-surgery-statistics (accessed on 8 February 2023).

- American Academy of Ophthalmology. Functional indications for upper and lower eyelid blepharoplasty. Ophthalmology 1995, 102, 693–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golchet, P.R.; Yu, F.; Goldberg, R.; Coleman, A.L. Recent trends in upper eyelid blepharoplasties in medicare patients in the United States from 1995 to 1999. Ophthalmic Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2004, 20, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, J. Complications following blepharoplasty. Plast. Surg. Nurs. 1998, 18, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghabrial, R.; Lisman, R.D.; Kane, M.A.; Milite, J.; Richards, R. Diplopia following transconjunctival blepharoplasty. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1998, 102, 1219–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Studdert, D.M.; Spittal, M.J.; Zhang, Y.; Wilkinson, D.S.; Singh, H.; Mello, M.M. Changes in Practice among Physicians with Malpractice Claims. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 1247–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svider, P.F.; Keeley, B.R.; Zumba, O.; Mauro, A.C.; Setzen, M.; Eloy, J.A. From the operating room to the courtroom: A comprehensive characterization of litigation related to facial plastic surgery procedures. Laryngoscope 2013, 123, 1849–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svider, P.F.; Blake, D.M.; Husain, Q.; Mauro, A.C.; Turbin, R.E.; Eloy, J.A.; Langer, P.D. In the eyes of the law: Malpractice litigation in oculoplastic surgery. Ophthalmic Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2014, 30, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holt, J.E.; Holt, G.R. Blepharoplasty. Indications and preoperative assessment. Arch. Otolaryngol. 1985, 111, 394–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klatsky, S.A.; Manson, P.N. Thyroid disorders masquerading as aging changes. Ann. Plast. Surg. 1992, 28, 420–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fulton, J.E. The complications of blepharoplasty: Their identification and management. Dermatol. Surg. 1999, 25, 549–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenthal, E.L.; Baker, S.R. Development of Graves orbitopathy after blepharoplasty. A rare complication. Arch. Facial Plast. Surg. 1999, 1, 127–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohrich, R.J.; Coberly, D.M.; Fagien, S.; Stuzin, J.M. Current concepts in aesthetic upper blepharoplasty. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2004, 113, 32e–42e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS). Practice Parameter for Blepharoplasty. Arlington Heights, IL. March 2007. Available online: http://www.plasticsurgery.org/Documents/medical-professionals/healthpolicy/evidence-practice/Blepharoplasty-Practice-Parameter.pdf (accessed on 30 September 2022).

- Trussler, A.P.; Rohrich, R.J. MOC-PSSM CME article: Blepharoplasty. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2008, 121 (Suppl. S1), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naik, M.N.; Honavar, S.G.; Das, S.; Desai, S.; Dhepe, N. Blepharoplasty: An overview. J. Cutan. Aesthetic Surg. 2009, 2, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedland, J.A.; Lalonde, D.H.; Rohrich, R.J. An evidence-based approach to blepharoplasty. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2010, 126, 2222–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drolet, B.C.; Sullivan, P.K. Evidence-based medicine: Blepharoplasty. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2014, 133, 1195–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Custer, P.L. Preoperative Examination Checklist for Upper Blepharoplasty. In Pearls and Pitfalls in Cosmetic Oculoplastic Surgery; Hartstein, M.D., Facs, M., Massry, M.D., Facs, G., Holds, M.D., Facs, J., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Italian Association of Aesthetics and Plastic Surgery (AICPE). Linee Guida Per I Principali Interventi Di Chirurgia Estetica. Minerva Chirurgica. Volume 70, Suppl. I, N. 6. Revised in 1 December 2015. Available online: https://www.aicpe.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/linee-guida-aggiornamento-2015.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2022).

- Italian Society of Reconstructive and Aesthetic Plastic Surgery (SICPRE). Prospetto Informativo Sull’intervento Di Blefaroplastica. 2015. Available online: https://www.sicpre.it/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/07.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2022).

- Scawn, R.; Gore, S.; Joshi, N. Blepharoplasty Basics for the Dermatologist. J. Cutan. Aesthetic Surg. 2016, 9, 80–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, K.; Misra, D.K.; Deori, N. Updates on upper eyelid blepharoplasty. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2017, 65, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauriello, J.A., Jr. Preoperative Evaluation of Patients Undergoing Cosmetic Blepharoplasty. In Ento Key, Fastest Otolaryngology & Ophthalmology Insight Engine; 2018. Available online: https://entokey.com/preoperative-evaluation-of-patients-undergoing-cosmetic-blepharoplasty/ (accessed on 12 October 2022).

- MassHealth. Guidelines for Medical Necessity Determination for Blepharoplasty, Upper Eyelid Ptosis, and Brow Ptosis Surgery. 25 October 2019. Available online: https://www.mass.gov/doc/guidelines-for-medical-necessity-determination-for-blepharoplasty-upper-eyelid-ptosis-and-brow-ptosis-surgery/download (accessed on 14 October 2022).

- Kim, K.; Granick, M.; Baum, G.; Beninger, F.; Cahill, K.; Kaidi, A.; Kang, A.; Loeding, L.; Li, M.L.; Patel, P.; et al. Evidence-based Clinical Practice Guideline: Eyelid Surgery for Upper Visual Field Improvement (Draft). American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS). 8 August 2019. Available online: https://www.plasticsurgery.org/documents/medical-professionals/quality-resources/guidelines/guideline-2019-upper-eyelind-brow-surgery.pdf (accessed on 22 June 2022).

- Caughlin, B.P. Browplasty. In Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, A Comprehensive Study Guide, 2nd ed.; Boeckmann, W.A., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 263–274. [Google Scholar]

- Kwitko, G.M.; Patel, B.C. Blepharoplasty Ptosis Surgery. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2021. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482296/?report=classic (accessed on 22 June 2022).

- Rebowe, R.E.; Runyan, C. Blepharoplasty. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2021. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482381/ (accessed on 22 June 2022).

- Lelli, G.J., Jr.; Lisman, R.D. Blepharoplasty complications. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2010, 125, 1007–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyams, A.L.; Brandenburg, J.A.; Lipsitz, S.R.; Shapiro, D.W.; Brennan, T.A. Practice guidelines and malpractice litigation: A two-way street. Ann. Intern. Med. 1995, 122, 450–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recupero, P.R. Clinical practice guidelines as learned treatises: Understanding their use as evidence in the courtroom. J. Am. Acad. Psychiatry Law 2008, 36, 290–301. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kandinov, A.; Mutchnick, S.; Nangia, V.; Svider, P.F.; Zuliani, G.F.; Shkoukani, M.A.; Carron, M.A. Analysis of Factors Associated with Rhytidectomy Malpractice Litigation Cases. JAMA Facial Plast. Surg. 2017, 19, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrara, S.D.; Baccino, E.; Boscolo-Berto, R.; Comandè, G.; Domenici, R.; Hernandez-Cueto, C.; Gulmen, M.K.; Mendelson, G.; Montisci, M.; Norelli, G.A.; et al. Padova Charter on personal injury and damage under civil-tort law: Medico-legal guidelines on methods of ascertainment and criteria of evaluation. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2016, 130, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fante, R.G.; Bucsi, R.; Wynkoop, K. Medical Professional Liability Claims: Experience in Oculofacial Plastic Surgery. Ophthalmology 2018, 125, 1996–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyll, P.; Kang, P.; Mahabir, R.; Bernard, R.W. Variables That Impact Medical Malpractice Claims Involving Plastic Surgeons in the United States. Aesthetic Surg. J. 2018, 38, 785–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author | Article Type | Indications/Contraindications to Blepharoplasty in Patients with Thyroid Conditions * |

|---|---|---|

| Holt J.E. et al. (1985) [9] | Classical article | “…When performing surgery in and around the eyelids, a complete ophthalmologic examination should be performed on every patient. This includes documentation of visual acuity, pupillary function, intraocular pressure, extraocular muscle balance, and ophthalmoscopic examination…” |

| Klatsky S.A. et al. (1992) [10] | Classical article | “…It is important when evaluating patients requesting cosmetic surgery that medical conditions simulating aging changes be considered…” |

| Fulton J.E. (1999) [11] | Classical article | “... After reviewing the history of the orbital area, the general health should be examined. Are there any systemic illnesses such as multiple sclerosis, thyroid imbalance, hypertension or diabetes?...” |

| Rosenthal E.L. et al. (1999) [12] | Case report | “… Given the development of symptoms in the immediate postoperative period, it is likely that blepharoplasty activated a previously subclinical GO [ed. GO: Graves Orbitopathy] …This is the first report of a patient with subclinical Graves disease developing GO after blepharoplasty. Although extremely rare, this case underscores the importance of preoperative screening for a previous history of thyroid or orbital diseases…” |

| Rohrich R.J. et al. (2004) [13] | Classical article | “...Medical and ophthalmologic histories must be obtained from the patient, including any history of chronic illness, hypertension, diabetes, cardiac disease, bleeding disorders, thyroid disturbances, or surgery...” |

| American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS) (2007) [14] | Practice guidelines | “...CONSULTATION: Preoperative consultation should evaluate the patient’s reasons for seeking surgery. Patients present with a variety of symptoms or combination of symptoms including edema, … dry eye, medications, allergies, history of eyelid swelling, thyroid disease, heart failure, and bleeding tendencies…” |

| Trussler A.P. et al. (2008) [15] | Review | “...Preoperative patient evaluation for blepharoplasty should document medical and ophthalmologic histories.1 This should include lifestyle history (smoking, exercise tolerance, and alcohol use), history of chronic illnesses, hypertension, diabetes, cardiac disease, bleeding and/or clotting disorders, thyroid disturbances, or previous operations. Medications, including aspirin and other anticoagulants, should be listed and withheld for at least 2 weeks preoperative...” |

| Naik M.N. et al. (2009) [16] | Review | “...Preoperative patient evaluation for blepharoplasty should document medical and ophthalmologic history such as chronic systemic diseases and medications. Ophthalmologic history should be obtained, including vision, corrective lenses, trauma, glaucoma, allergic reactions, excess tearing, and dry eyes…” |

| Friedland J.A. et al. (2010) [17] | Review | “...Preoperative patient evaluation for blepharoplasty should include general medical and periorbital histories…bleeding and/or clotting disorders, thyroid problems, and chronic illnesses, such as diabetes and hypertension, should be documented…” |

| Drolet B.C. et al. (2014) [18] | Review | “...All patients require a thorough medical history. Comorbidities should be noted, including hypertension, diabetes mellitus, bleeding disorders, and thyroid disease, along with significant chronic illnesses that would preclude an aesthetic operation…A detailed ophthalmologic history, including prior trauma or surgery, visual disturbances, and dry eyes, should be obtained…” |

| Custer P.L. (2014) [19] | Book chapter | “...Patients with the following conditions may be at higher risk for complications following blepharoplasty or require specialized surgical techniques: unrealistic expectations, prior eyelid/facial surgery, dry eye symptoms, thyroid disease, prominent eyes, marked orbital asymmetry, significant coexisting medical problems...” |

| Italian Association of Aesthetics and Plastic Surgery (AICPE) (2015) [20] | Guidelines | “…it is preferable to avoid surgery in case of: alterations in coagulation, hypertension or precarious general conditions... if there is any doubt about ocular pathology, it is advisable to have an ophthalmological examination. Blood tests are recommended: blood count, PT, PTT and glycaemia…” |

| Italian Society of Reconstructive and Aesthetic Plastic Surgery (SICPRE) (2015) [21] | Information from guidelines | “…Before proceeding with corrective blepharoplasty, the patient may be advised to undergo an eye examination which must include the determination of the visual field and the measurement of the ocular tone. Thyroid function screening tests may be required in special cases and especially for women…“ |

| Scawn R. et al. (2016) [22] | Classical article | “…Before considering blepharoplasty, potential contraindications to surgery should be elucidated; these include patients with psychological issues, dry eyes, active inflammatory cicatrising skin conditions such as eczema and psoriasis and multi-revision surgeries…” |

| Bhattacharjee K. et al. (2017) [23] | Review | “...complete medical and ocular history should be obtained, along with a thorough ophthalmologic examination. A proper history of any trauma or previous surgery should be recorded. Patients should be evaluated for thyroid disease and dry eye disease. Seventh nerve function should also be evaluated...”. |

| Joseph A. et al. (2018) [24] | Book chapter | “…Eyelid retraction, lid lag on downgaze and lagophthalmos, and decreased convergence may be found in patients with thyroid-related orbitopathy. Blepharoplasty should be reserved for patients with quiescent disease and undertaken after any proptosis, motility dysfunction, and eyelid retraction have stabilized for 6 months to 1 year or have been definitively treated. In patients with suspected thyroid eye disease, referral to an endocrinologist or internist may be necessary for appropriate systemic workup, including serum thyroid hormone levels (triiodothyronine [T3], levorotatory thyroxine [T4], thyroid stimulating hormone [TSH]). Orbital computed tomography may demonstrate enlargement of the extraocular muscles and increased orbital fat when systemic signs are completely lacking early in the course of the disease…” |

| MassHealth (2019) [25] | Guidelines | “...Any related disease process, such as myasthenia gravis or thyroid condition or oculomotor nerve palsy, is documented as stable and with optimal medical management prior to the consideration of surgery;...” |

| Kim K. et al. (2019) [26] | Guideline draft | “...The initial patient evaluation should include general medical and periorbital history. A detailed medical and focused history should document elements of previous eye and eyelid surgery, cardiac and chronic illness, bleeding disorders, medications and smoking…A physical examination should be performed. The eye examination should consist of basic visual acuity, extraocular muscle and pupil evaluation, and Bell’s phenomenon for corneal protection…” |

| Caughlin B.P. (2020) [27] | Book chapter | “…Relative contraindications to blepharoplasty: Actinic changes, acne rosacea, keloids, herpes zoster, thyroid abnormalities, autoimmune diseases, smoking history, extensive history of dry eye syndrome, and acute angle glaucoma history. Generally, should wait approximately 6 months after LASIK or PRK (exact timing varies depending on the source)…” |

| Kwitko G.M. et al. (2021) [28] | Review | “...Most contraindications for ptosis surgery revolve around the exposure of the cornea. Conditions like thyroid orbitopathy, progressive external ophthalmoplegia, or loss of Bell’s phenomenon can make patients more prone to exposure keratopathy after ptosis surgery: a more conservative approach is needed in these patients…CT scan of the orbits should be obtained if an orbital process such as thyroid orbitopathy or an orbital tumor is suspected. Slit lamp evaluation is essential to detect corneal erosions or dry eye…” |

| Rebowe R.E. et al. (2021) [29] | Review | “…All patients undergoing eyelid procedures should be questioned regarding ophthalmologic pathology and should receive a full eye exam, complete with the retinal examination. Specifically, patients should be questioned regarding preoperative visual acuity, symptoms of dry eyes, and visual obstruction. Furthermore, the full medical history should include pathology related to systemic disease with ophthalmologic manifestations, including thyroid disease, diabetes, hypertension, or inflammatory diseases treated with steroids. A history of bleeding or clotting disorders should also be elicited…) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Defraia, B.; Focardi, M.; Grassi, S.; Chiavacci, G.; Faccioli, S.; Romano, G.F.; Bianchi, I.; Pinchi, V.; Innocenti, A. Negative Outcomes of Blepharoplasty and Thyroid Disorders: Is Compensation Always Due? A Case Report with a Literature Review. Diseases 2024, 12, 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases12040075

Defraia B, Focardi M, Grassi S, Chiavacci G, Faccioli S, Romano GF, Bianchi I, Pinchi V, Innocenti A. Negative Outcomes of Blepharoplasty and Thyroid Disorders: Is Compensation Always Due? A Case Report with a Literature Review. Diseases. 2024; 12(4):75. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases12040075

Chicago/Turabian StyleDefraia, Beatrice, Martina Focardi, Simone Grassi, Giulia Chiavacci, Simone Faccioli, Gianmaria Federico Romano, Ilenia Bianchi, Vilma Pinchi, and Alessandro Innocenti. 2024. "Negative Outcomes of Blepharoplasty and Thyroid Disorders: Is Compensation Always Due? A Case Report with a Literature Review" Diseases 12, no. 4: 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases12040075

APA StyleDefraia, B., Focardi, M., Grassi, S., Chiavacci, G., Faccioli, S., Romano, G. F., Bianchi, I., Pinchi, V., & Innocenti, A. (2024). Negative Outcomes of Blepharoplasty and Thyroid Disorders: Is Compensation Always Due? A Case Report with a Literature Review. Diseases, 12(4), 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases12040075