Pneumonia-Related Hospitalizations among the Elderly: A Retrospective Study in Northeast Italy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population and Data Source

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Health Outcomes and Costs

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Ethics Statement

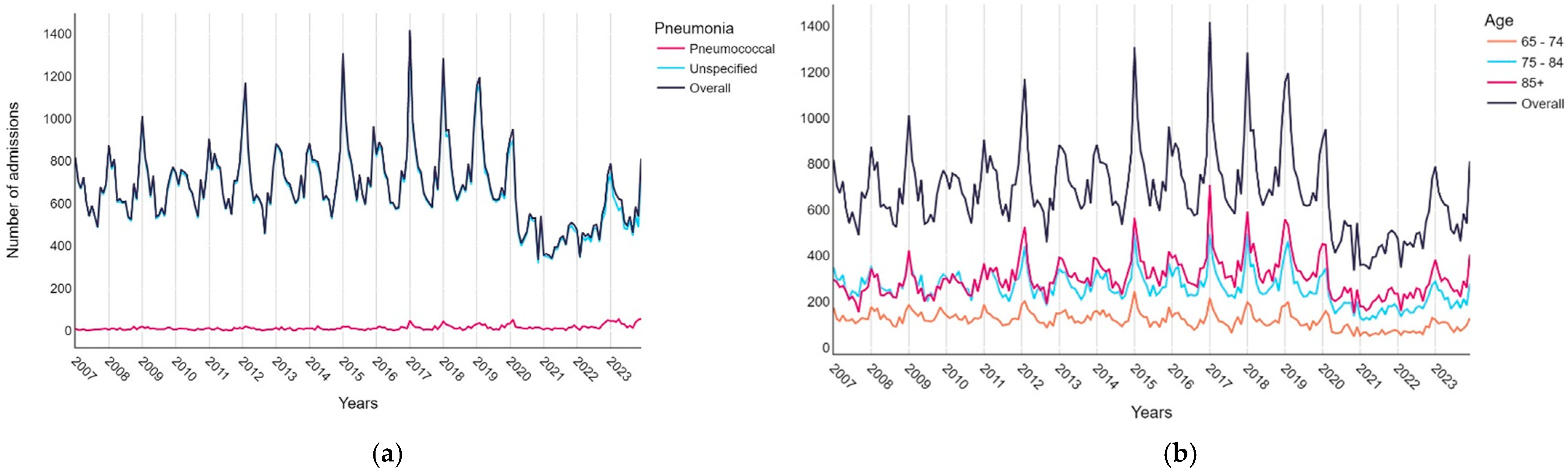

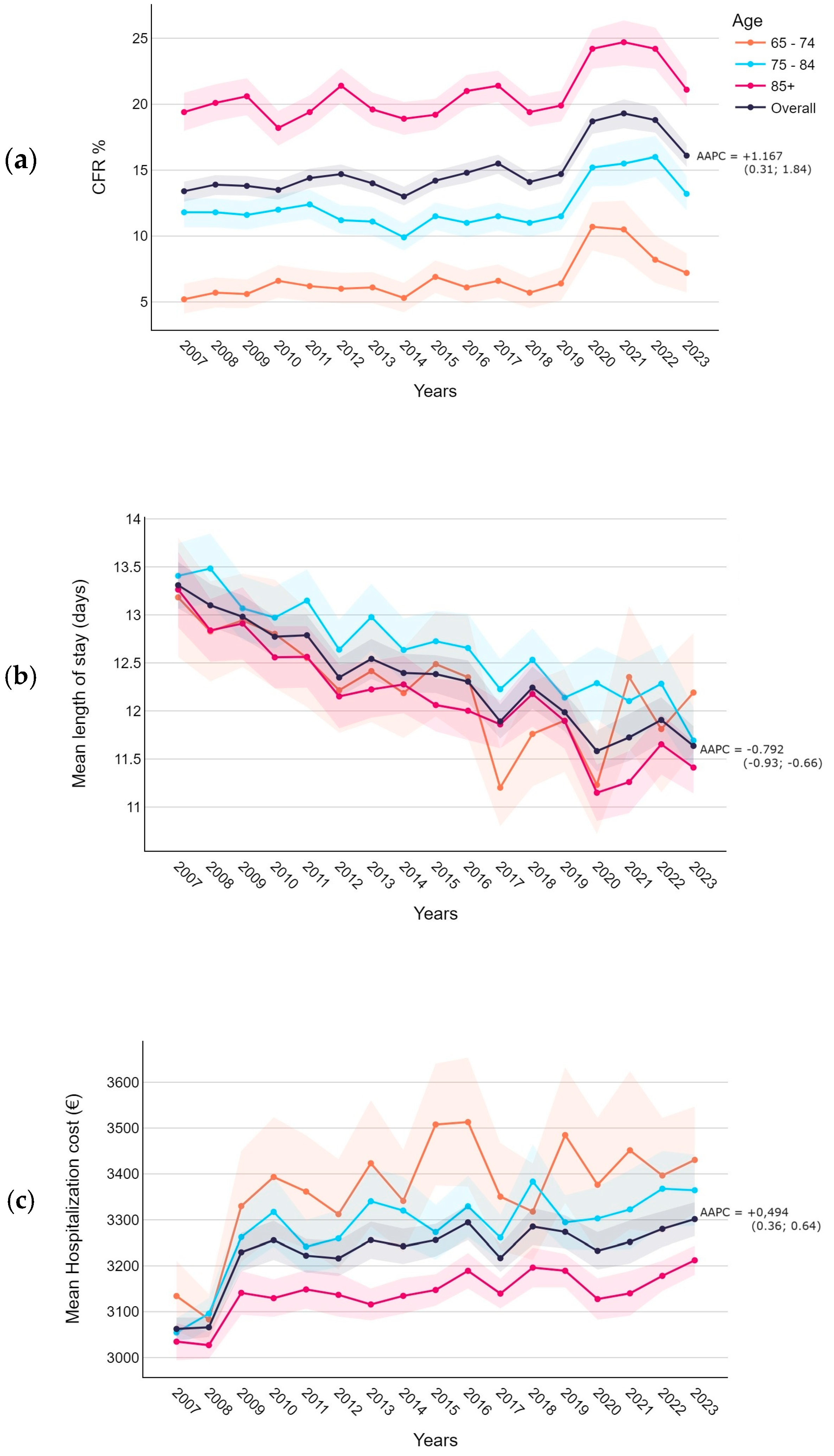

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variable | Pneumonia | Total (N = 139,201) | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pneumococcal (N = 2843) | Unspecified (N = 136,358) | ||||

| Age at hospitalization | Min/Max | 65.0/105.0 | 65.0/121.0 | 65.0/121.0 | <0.0001 |

| Med [IQR] | 80.0 [73.0;87.0] | 83.0 [77.0;89.0] | 83.0 [77.0;89.0] | ||

| Mean (std) | 80.2 (8.5) | 82.7 (7.9) | 82.7 (7.9) | ||

| Age group at hospitalization | 65–74 | 808 (28.4%) | 23,306 (17.1%) | 24,114 (17.3%) | <0.0001 |

| 75–84 | 1102 (38.8%) | 52,046 (38.2%) | 53,148 (38.2%) | ||

| 85+ | 933 (32.8%) | 61,006 (44.7%) | 61,939 (44.5%) | ||

| Sex | Female | 1381 (48.6%) | 66,561 (48.8%) | 67,942 (48.8%) | 0.8016 |

| Male | 1462 (51.4%) | 69,797 (51.2%) | 71,259 (51.2%) | ||

| Other diagnosed invasive bacterial diseases | Meningitis | 17 (0.6%) | 51 (0.04%) | 68 (0.05%) | <0.0001 |

| Septicemia | 297 (10.4%) | 5822 (4.3%) | 6119 (4.4%) | <0.0001 | |

| Empyema | 31 (1.1%) | 188 (0.1%) | 219 (0.2%) | <0.0001 | |

| Admission season | Winter | 990 (34.8%) | 42,259 (31.0%) | 43,249 (31.1%) | <0.0001 |

| Spring | 694 (24.4%) | 33,094 (24.3%) | 33,788 (24.3%) | ||

| Summer | 383 (13.5%) | 29,272 (21.5%) | 29,655 (21.3%) | ||

| Autumn | 776 (27.3%) | 31,733 (23.3%) | 32,509 (23.4%) | ||

| Comorbidities | Cardiovascular diseases | 639 (22.5%) | 40,265 (29.5%) | 40,904 (29.4%) | <0.0001 |

| COPD | 296 (10.4%) | 13,476 (9.9%) | 13,772 (9.9%) | 0.3500 | |

| Moderate–severe CKD | 164 (5.8%) | 9097 (6.7%) | 9261 (6.7%) | 0.0559 | |

| Diabetes | 314 (11.0%) | 15,097 (11.1%) | 15,411 (11.1%) | 0.9639 | |

| Neoplasms | 190 (6.7%) | 7394 (5.4%) | 7584 (5.4%) | 0.0034 | |

| Other comorbidities | 367 (12.9%) | 18,883 (13.8%) | 19,250 (13.8%) | 0.1511 | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | Min/Max | 2.0/14.0 | 2.0/18.0 | 2.0/18.0 | <0.0001 |

| Med [IQR] | 4.0 [3.0;5.0] | 4.0 [4.0;5.0] | 4.0 [4.0;5.0] | ||

| Mean (std) | 4.5 (1.8) | 4.6 (1.5) | 4.6 (1.5) | ||

| Deceased (CFR%) | 284 (10.0%) | 20,422 (15.0%) | 20,706 (14.9%) | <0.0001 | |

| Length of stay (days) | Min/Max | 0/91.0 | 0/501.0 | 0/501.0 | <0.0001 |

| Med [IQR] | 11.0 [7.0;15.0] | 10.0 [7.0;15.0] | 10.0 [7.0;15.0] | ||

| Mean (std) | 12.8 (9.0) | 12.4 (9.9) | 12.4 (9.9) | ||

| Hospitalization cost (EUR) | Min/Max | 200.0/3.7 × 104 | 200.0/6.8 × 104 | 200.0/6.8 × 104 | <0.0001 |

| Med [IQR] | 3307.1 [3307.1;3307.1] | 3307.1 [2445.4;3307.1] | 3307.1 [2445.4;3307.1] | ||

| Mean (std) | 3706.6 (2659.8) | 3223.1 (1704.7) | 3232.9 (1730.7) | ||

| N (NA) | 2826 (17) | 135,884 (474) | 138,710 (491) | ||

| Hospitalization cost per day (EUR) | Min/Max | 68.3/6619.8 | 5.7/1.3 × 104 | 5.7/1.3 × 104 | <0.0001 |

| Med [IQR] | 300.6 [206.7;450.9] | 300.6 [200.0;413.4] | 300.6 [200.0;413.4] | ||

| Mean (std) | 392.9 (387.3) | 371.1 (314.9) | 371.6 (316.5) | ||

| N (NA) | 2826 (17) | 135,884 (474) | 138,710 (491) | ||

| DRG type | Surgical | 47 (1.7%) | 904 (0.7%) | 951 (0.7%) | <0.0001 |

| Medical | 2779 (98.3%) | 134,980 (99.3%) | 137,759 (99.3%) | ||

| NA | 17 | 474 | 491 | ||

| Emergency admission | 2766 (97.3%) | 125,442 (92.0%) | 128,208 (92.1%) | <0.0001 | |

References

- Tsoumani, E.; Carter, J.A.; Salomonsson, S.; Stephens, J.M.; Bencina, G. Clinical, Economic, and Humanistic Burden of Community Acquired Pneumonia in Europe: A Systematic Literature Review. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2023, 22, 876–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regunath, H.; Oba, Y. Community-Acquired Pneumonia. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Gadsby, N.J.; Musher, D.M. The Microbial Etiology of Community-Acquired Pneumonia in Adults: From Classical Bacteriology to Host Transcriptional Signatures. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2022, 35, e00015-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyun, H.; Song, J.Y.; Yoon, J.G.; Seong, H.; Noh, J.Y.; Cheong, H.J.; Kim, W.J. Risk Factor-Based Analysis of Community-Acquired Pneumonia, Healthcare-Associated Pneumonia and Hospital-Acquired Pneumonia: Microbiological Distribution, Antibiotic Resistance, and Clinical Outcomes. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0270261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Pneumonia. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/pneumonia (accessed on 19 June 2024).

- Cillóniz, C.; Rodríguez-Hurtado, D.; Torres, A. Characteristics and Management of Community-Acquired Pneumonia in the Era of Global Aging. Med. Sci. 2018, 6, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pneumonia: Learn More—Pneumonia in Older People: What You Should Know. In InformedHealth.org [Internet]; Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG): Cologne, Germany, 2021.

- Yoshimatsu, Y.; Thomas, H.; Thompson, T.; Smithard, D.G. Prognostic Factors of Poor Outcomes in Pneumonia in Older Adults: Aspiration or Frailty? Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2024, 15, 481–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, J.-K.; Kao, H.-H.; Kao, Y.-H. Factors Associated with Hospitalized Community-Acquired Pneumonia among Elderly Patients Receiving Home-Based Care. Healthcare 2024, 12, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niederman, M.S. Natural Enemy or Friend? Pneumonia in the Very Elderly Critically Ill Patient. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2020, 29, 200031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, C.; Nunes, M.C.; Saadatian-Elahi, M. Epidemiology of Community-Acquired Pneumonia Caused by S Treptococcus Pneumoniae in Older Adults: A Narrative Review. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2024, 37, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gierke, R.; Wodi, A.P.; Kobayashi, M.; CDC. Chapter 17: Pneumococcal Disease. In Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases, 14th ed.; Communication and Education Branch, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Anastassopoulou, C.; Ferous, S.; Medić, S.; Siafakas, N.; Boufidou, F.; Gioula, G.; Tsakris, A. Vaccines for the Elderly and Vaccination Programs in Europe and the United States. Vaccines 2024, 12, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullard, A. FDA Approves 21-Valent Pneumococcal Vaccine. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2024, 23, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, R. Pneumococco: Bersaglio in Movimento. In I Vaccini in Pediatria: Tra Principi e Pratica Clinica; Corsello, G., Staiano, A., Villani, A., Eds.; Pacini Editore Medicina: Pisa, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Baldo, V.; Cocchio, S.; Gallo, T.; Furlan, P.; Clagnan, E.; Del Zotto, S.; Saia, M.; Bertoncello, C.; Buja, A.; Baldovin, T. Impact of Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccination: A Retrospective Study of Hospitalization for Pneumonia in North-East Italy. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2016, 57, E61–E68. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jimbo Sotomayor, R.; Toscano, C.M.; Sánchez Choez, X.; Vilema Ortíz, M.; Rivas Condo, J.; Ghisays, G.; Haneuse, S.; Weinberger, D.M.; McGee, G.; de Oliveira, L.H. Impact of Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine on Pneumonia Hospitalization and Mortality in Children and Elderly in Ecuador: Time Series Analyses. Vaccine 2020, 38, 7033–7039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reyburn, R.; Tsatsaronis, A.; von Mollendorf, C.; Mulholland, K.; Russell, F.M. ARI Review group Systematic Review on the Impact of the Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine Ten Valent (PCV10) or Thirteen Valent (PCV13) on All-Cause, Radiologically Confirmed and Severe Pneumonia Hospitalisation Rates and Pneumonia Mortality in Children 0–9 Years Old. J. Glob. Health 2023, 13, 05002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OOSGA GDP of Italy in 2023: GDP Structure & Regional GDP per Capita. Available online: https://oosga.com/gdp/ita/ (accessed on 18 June 2024).

- Demographic Statistics Veneto Region (Population Density, Population, Median Age, Households, Foreigners). Available online: https://ugeo.urbistat.com/AdminStat/it/it/demografia/dati-sintesi/veneto/5/2 (accessed on 18 June 2024).

- Ferre, F.; de Belvis, A.G.; Valerio, L.; Longhi, S.; Lazzari, A.; Fattore, G.; Ricciardi, W.; Maresso, A. Italy: Health System Review. Health Syst. Transit. 2014, 16, 1–168. [Google Scholar]

- Regione del Veneto. Decree No. 118 of December 23th, 2016. Aggiornamento Della Disciplina Del Flusso Informativo “Scheda Di Dimissione Ospedaliera” e Dei Tracciati Record. Available online: https://salute.regione.veneto.it/c/document_library/get_file?p_l_id=8278039&folderId=1026448&name=DLFE-31626.pdf (accessed on 18 June 2024).

- Sanjay Sethi Overview of Pneumonia. Available online: https://www.msdmanuals.com/professional/pulmonary-disorders/pneumonia/overview-of-pneumonia (accessed on 28 August 2024).

- Istat (Istituto Nazionale di Statistica). Demo—Statistiche Demografiche. Available online: https://demo.istat.it/?l=it (accessed on 18 June 2024).

- Charlson, M.E.; Pompei, P.; Ales, K.L.; MacKenzie, C.R. A New Method of Classifying Prognostic Comorbidity in Longitudinal Studies: Development and Validation. J. Chronic Dis. 1987, 40, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regione del Veneto. Allegato A. Tariffe DRG. Available online: https://salute.regione.veneto.it/c/document_library/get_file?p_l_id=8278039&folderId=1026448&name=DLFE-32075.xls (accessed on 28 August 2024).

- Statistical Methodology and Applications Branch, Surveillance Research Program, National Cancer Institute. Joinpoint Regression Program 2023. Available online: https://surveillance.cancer.gov/help/joinpoint (accessed on 28 August 2024).

- Amodio, E.; Vitale, F.; d’Angela, D.; Carrieri, C.; Polistena, B.; Spandonaro, F.; Pagliaro, A.; Montuori, E.A. Increased Risk of Hospitalization for Pneumonia in Italian Adults from 2010 to 2019: Scientific Evidence for a Call to Action. Vaccines 2023, 11, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Prieto, R.; Allouch, N.; Jimeno, I.; Hernández-Barrera, V.; Arguedas-Sanz, R.; Gil-de-Miguel, Á. Burden of Hospitalizations Related to Pneumococcal Infection in Spain (2016–2020). Antibiotics 2023, 12, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertran, M.; D’Aeth, J.C.; Abdullahi, F.; Eletu, S.; Andrews, N.J.; Ramsay, M.E.; Litt, D.J.; Ladhani, S.N. Invasive Pneumococcal Disease 3 Years after Introduction of a Reduced 1 + 1 Infant 13-Valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine Immunisation Schedule in England: A Prospective National Observational Surveillance Study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 546–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, T.; Denouel, A.; Tietjen, A.K.; Lee, J.W.; Falsey, A.R.; Demont, C.; Nyawanda, B.O.; Cai, B.; Fuentes, R.; Stoszek, S.K.; et al. Global and Regional Burden of Hospital Admissions for Pneumonia in Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 222, S570–S576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corica, B.; Tartaglia, F.; D’Amico, T.; Romiti, G.F.; Cangemi, R. Sex and Gender Differences in Community-Acquired Pneumonia. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2022, 17, 1575–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, A.; Cillóniz, C.; Blasi, F.; Chalmers, J.D.; Gaillat, J.; Dartois, N.; Schmitt, H.-J.; Welte, T. Burden of Pneumococcal Community-Acquired Pneumonia in Adults across Europe: A Literature Review. Respir. Med. 2018, 137, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghia, C.J.; Rambhad, G.S. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Comorbidities and Associated Risk Factors in Indian Patients of Community-Acquired Pneumonia. SAGE Open Med. 2022, 10, 20503121221095485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corrales-Medina, V.F.; Alvarez, K.N.; Weissfeld, L.A.; Angus, D.C.; Chirinos, J.A.; Chang, C.-C.H.; Newman, A.; Loehr, L.; Folsom, A.R.; Elkind, M.S.; et al. Association Between Hospitalization for Pneumonia and Subsequent Risk of Cardiovascular Disease. JAMA 2015, 313, 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Tian, Q.; Xu, R.; Zhong, C.; Qiu, L.; Zhang, H.; Shi, C.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, Y. Short-Term Exposure to Ambient Air Pollution and Pneumonia Hospital Admission among Patients with COPD: A Time-Stratified Case-Crossover Study. Respir. Res. 2022, 23, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivero-Calle, I.; Cebey-López, M.; Pardo-Seco, J.; Yuste, J.; Redondo, E.; Vargas, D.A.; Mascarós, E.; Díaz-Maroto, J.L.; Linares-Rufo, M.; Jimeno, I.; et al. Lifestyle and Comorbid Conditions as Risk Factors for Community-Acquired Pneumonia in Outpatient Adults (NEUMO-ES-RISK Project). BMJ Open Respir. Res. 2019, 6, e000359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idigo, A.J.; Wells, J.M.; Brown, M.L.; Wiener, H.W.; Griffin, R.L.; Cutter, G.; Shrestha, S.; Lee, R.A. Socio-Demographic and Comorbid Risk Factors for Poor Prognosis in Patients Hospitalized with Community-Acquired Bacterial Pneumonia in Southeastern US. Heart Lung 2024, 65, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pessoa, E.; Bárbara, C.; Viegas, L.; Costa, A.; Rosa, M.; Nogueira, P. Factors Associated with In-Hospital Mortality from Community-Acquired Pneumonia in Portugal: 2000–2014. BMC Pulm. Med. 2020, 20, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, R.; Hatakeyama, Y.; Kitazawa, T.; Matsumoto, K.; Fujita, S.; Seto, K.; Hasegawa, T. Capturing the Trends in Hospital Standardized Mortality Ratios for Pneumonia: A Retrospective Observational Study in Japan (2010 to 2018). Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2020, 25, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vissink, C.E.; Huijts, S.M.; de Wit, G.A.; Bonten, M.J.M.; Mangen, M.-J.J. Hospitalization Costs for Community-Acquired Pneumonia in Dutch Elderly: An Observational Study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campling, J.; Wright, H.F.; Hall, G.C.; Mugwagwa, T.; Vyse, A.; Mendes, D.; Slack, M.P.E.; Ellsbury, G.F. Hospitalization Costs of Adult Community-Acquired Pneumonia in England. J. Med. Econ. 2022, 25, 912–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regione del Veneto Coperture Vaccinali—Report Sull’attività Vaccinale Dell’anno 2022. Available online: https://www.vaccinarsinveneto.org/vaccinazioni-veneto/coperture-vaccinali (accessed on 28 August 2024).

| Pneumonia-Related Hospitalization Discharge Diagnoses Group | International Classification of Diseases 9 Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) Codes | |

|---|---|---|

| First-Listed Discharge Diagnosis | Another Discharge Diagnosis | |

| Pneumococcal pneumonia [S. pneumoniae pneumonia] | 481 | |

| Unspecified pneumonia [pneumonia without a causative organism identified] | 485–487; 482.9 | |

| Meningitis | 321, 013.0, 003.21, 036.0, 036.1, 047, 047.0, 047.1, 047.8, 047.9, 049.1, 053.0, 054.72, 072.1, 091.81, 094.2, 098.82, 100.81, 112.83, 114.2, 115.01, 115.11, 115.91, 130.0, 320, 320.0, 320.1, 320.2, 320.3, 320.7, 320.81, 320.82, 320.89, 320.8, 320.9, 322, 322.0, 322.9 | Plus 481; 485–487; 482.9 |

| Septicemia | 038.1, 038.4, 003.1, 020.2, 022.3, 031.2, 036.2, 038, 038.0, 038.2, 038.3, 038.8, 038.9, 054.5, 790.7 | Plus 481; 485–487; 482.9 |

| Empyema | 510 | Plus 481; 485–487; 482.9 |

| Variable | Age Hospitalization | Total (N = 139,201) | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 65–74 (N = 24114) | 75–84 (N = 53,148) | 85+ (N = 61,939) | ||||

| Age hospitalization | Min/Max | 65.0/74.0 | 75.0/84.0 | 85.0/121.0 | 65.0/121.0 | <0.0001 |

| Med [IQR] | 71.0 [68.0;73.0] | 80.0 [78.0;83.0] | 89.0 [87.0;92.0] | 83.0 [77.0;89.0] | ||

| Mean (std) | 70.2 (2.8) | 80.0 (2.8) | 89.8 (3.8) | 82.7 (7.9) | ||

| Sex | Female | 8924 (37.0%) | 22,579 (42.5%) | 36,439 (58.8%) | 67,942 (48.8%) | <0.0001 |

| Male | 15,190 (63.0%) | 30,569 (57.5%) | 25,500 (41.2%) | 71,259 (51.2%) | ||

| Pneumonia | Pneumococcal | 808 (3.4%) | 1102 (2.1%) | 933 (1.5%) | 2843 (2.0%) | <0.0001 |

| Unspecified | 23,306 (96.6%) | 52,046 (97.9%) | 61,006 (98.5%) | 136,358 (98.0%) | ||

| Other diagnosed invasive diseases | Meningitis | 32 (0.1%) | 24 (0.05%) | 12 (0.02%) | 68 (0.05%) | <0.0001 |

| Septicemia | 1084 (4.5%) | 2388 (4.5%) | 2647 (4.3%) | 6119 (4.4%) | 0.1375 | |

| Empyema | 94 (0.4%) | 86 (0.2%) | 39 (0.1%) | 219 (0.2%) | <0.0001 | |

| Admission season | Winter | 7591 (31.5%) | 16,568 (31.2%) | 19,090 (30.8%) | 43,249 (31.1%) | 0.0020 |

| Spring | 6012 (24.9%) | 12,868 (24.2%) | 14,908 (24.1%) | 33,788 (24.3%) | ||

| Summer | 4933 (20.5%) | 11,391 (21.4%) | 13,331 (21.5%) | 29,655 (21.3%) | ||

| Autumn | 5578 (23.1%) | 12,321 (23.2%) | 14,610 (23.6%) | 32,509 (23.4%) | ||

| Comorbidities | Cardiovascular diseases | 3989 (16.5%) | 14,671 (27.6%) | 22,244 (35.9%) | 40,904 (29.4%) | <0.0001 |

| COPD | 2816 (11.7%) | 6117 (11.5%) | 4839 (7.8%) | 13,772 (9.9%) | <0.0001 | |

| Moderate–severe CKD | 1471 (6.1%) | 3397 (6.4%) | 4393 (7.1%) | 9261 (6.7%) | <0.0001 | |

| Diabetes | 3381 (14.0%) | 6368 (12.0%) | 5662 (9.1%) | 15,411 (11.1%) | <0.0001 | |

| Neoplasms | 2296 (9.5%) | 3326 (6.3%) | 1962 (3.2%) | 7584 (5.4%) | <0.0001 | |

| Other comorbidities | 2156 (8.9%) | 6634 (12.5%) | 10,460 (16.9%) | 19,250 (13.8%) | <0.0001 | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | Min/Max | 2.0/17.0 | 3.0/17.0 | 4.0/18.0 | 2.0/18.0 | <0.0001 |

| Med [IQR] | 3.0 [3.0;4.0] | 4.0 [4.0;5.0] | 5.0 [4.0;5.0] | 4.0 [4.0;5.0] | ||

| Mean (std) | 3.7 (1.7) | 4.6 (1.5) | 5.0 (1.3) | 4.6 (1.5) | ||

| Deceased (CFR%) | 1574 (6.5%) | 6377 (12.0%) | 12,755 (20.6%) | 20,706 (14.9%) | <0.0001 | |

| Length of stay (days) | Min/Max | 0/288.0 | 0/194.0 | 0/501.0 | 0/501.0 | <0.0001 |

| Med [IQR] | 10.0 [7.0;15.0] | 10.0 [7.0;15.0] | 10.0 [7.0;15.0] | 10.0 [7.0;15.0] | ||

| Mean (std) | 12.3 (10.5) | 12.7 (9.8) | 12.1 (9.7) | 12.4 (9.9) | ||

| Hospitalization cost (EUR) | Min/Max | 200.0/4.3 × 104 | 200.0/3.8 × 104 | 200.0/6.8 × 104 | 200.0/6.8 × 104 | <0.0001 |

| Med [IQR] | 3307.1 [2445.4;3307.1] | 3307.1 [2445.4;3307.1] | 3307.1 [2445.4;3307.1] | 3307.1 [2445.4;3307.1] | ||

| Mean (std) | 3360.3 (2370.9) | 3278.7 (1885.3) | 3144.2 (1217.3) | 3232.9 (1730.7) | ||

| N (NA) | 23,981 (133) | 52,934 (214) | 61,795 (144) | 138,710 (491) | ||

| Hospitalization cost per day (EUR) | Min/Max | 68.3/6682.9 | 5.7/1.3 × 104 | 80.9/9924.2 | 5.7/1.3 × 104 | <0.0001 |

| Med [IQR] | 300.6 [206.7;416.2] | 300.6 [200.0;413.4] | 300.6 [200.0;413.4] | 300.6 [200.0;413.4] | ||

| Mean (std) | 379.8 (339.3) | 362.6 (314.2) | 376.1 (309.1) | 371.6 (316.5) | ||

| N (NA) | 23,981 (133) | 52,934 (214) | 61,795 (144) | 138,710 (491) | ||

| DRG type | Surgical | 406 (1.7%) | 398 (0.8%) | 147 (0.2%) | 951 (0.7%) | <0.0001 |

| Medical | 23,575 (98.3%) | 52,536 (99.2%) | 61,648 (99.8%) | 137,759 (99.3%) | ||

| NA | 133 | 214 | 144 | 491 | ||

| Emergency admission | 21,835 (90.5%) | 48,738 (91.7%) | 57,635 (93.1%) | 128,208 (92.1%) | <0.0001 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cocchio, S.; Cozzolino, C.; Furlan, P.; Cozza, A.; Tonon, M.; Russo, F.; Saia, M.; Baldo, V. Pneumonia-Related Hospitalizations among the Elderly: A Retrospective Study in Northeast Italy. Diseases 2024, 12, 254. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases12100254

Cocchio S, Cozzolino C, Furlan P, Cozza A, Tonon M, Russo F, Saia M, Baldo V. Pneumonia-Related Hospitalizations among the Elderly: A Retrospective Study in Northeast Italy. Diseases. 2024; 12(10):254. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases12100254

Chicago/Turabian StyleCocchio, Silvia, Claudia Cozzolino, Patrizia Furlan, Andrea Cozza, Michele Tonon, Francesca Russo, Mario Saia, and Vincenzo Baldo. 2024. "Pneumonia-Related Hospitalizations among the Elderly: A Retrospective Study in Northeast Italy" Diseases 12, no. 10: 254. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases12100254

APA StyleCocchio, S., Cozzolino, C., Furlan, P., Cozza, A., Tonon, M., Russo, F., Saia, M., & Baldo, V. (2024). Pneumonia-Related Hospitalizations among the Elderly: A Retrospective Study in Northeast Italy. Diseases, 12(10), 254. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases12100254