The Governance of PPP Project Resilience: A Hybrid DMATEL-ISM Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Project Resilience in PPPs

2.2. Governance Factors for PPP Project Resilience

3. Research Methods

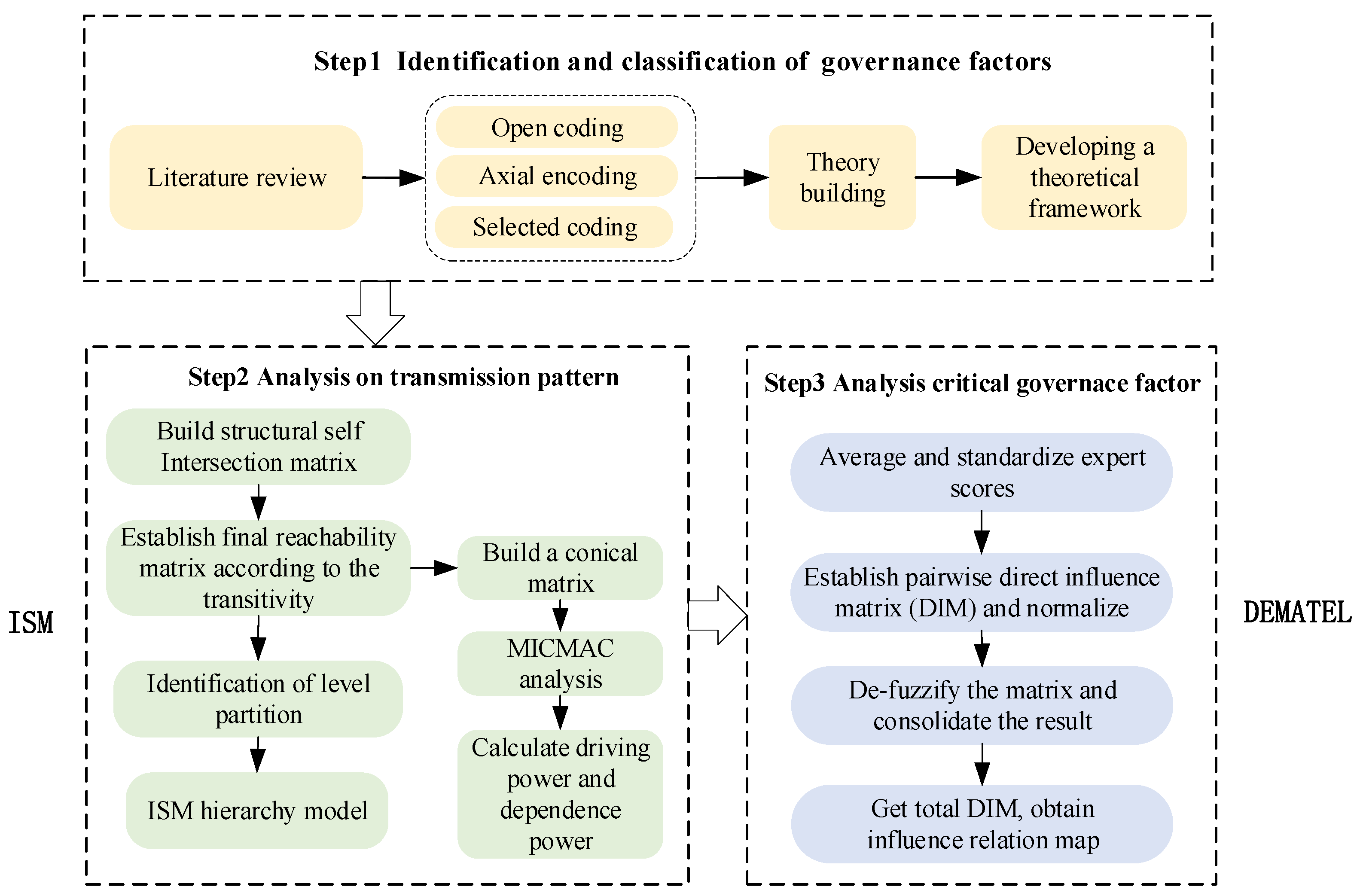

3.1. Research Design

3.2. ISM

3.3. DEMATEL

4. Results and Analysis

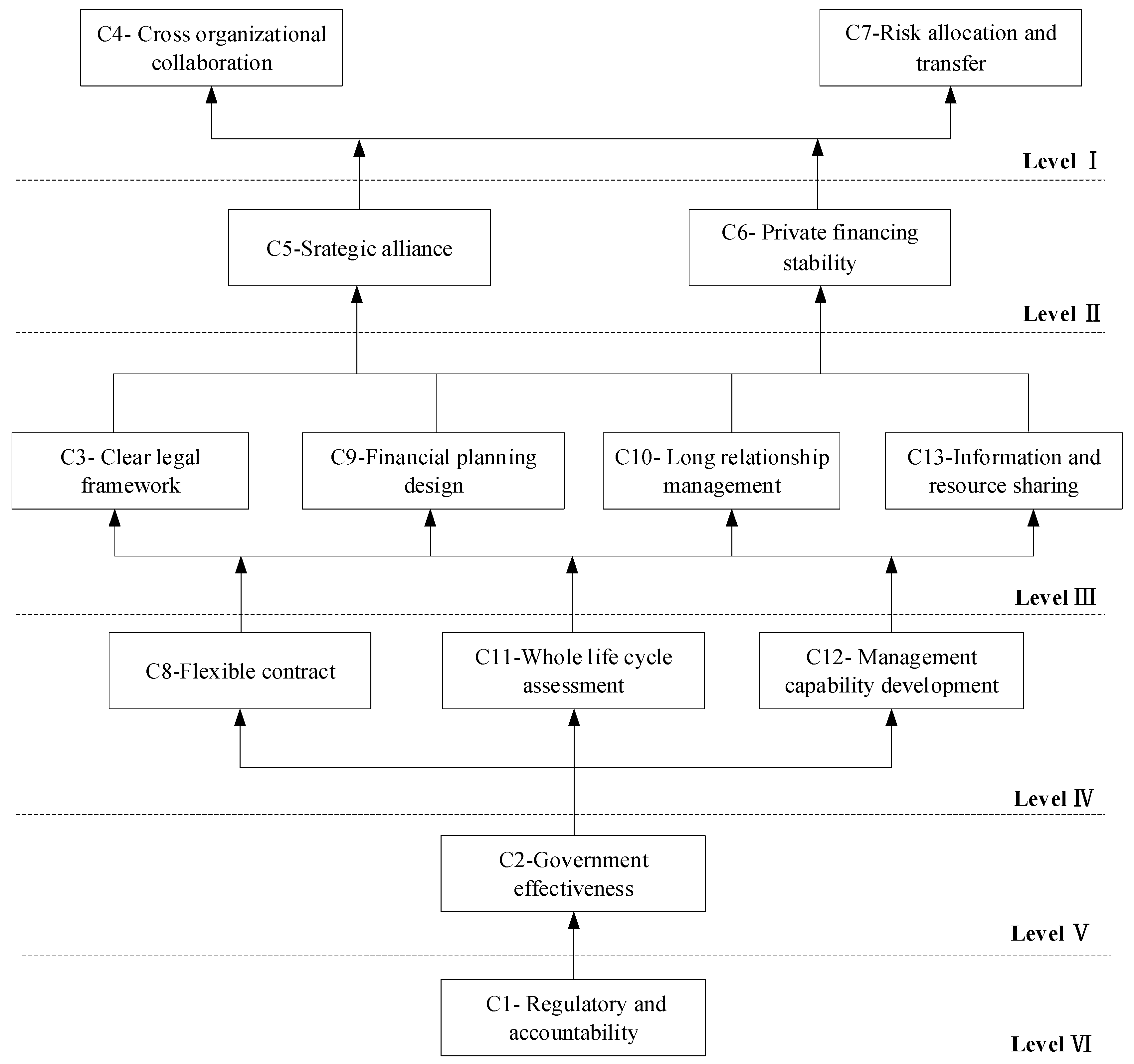

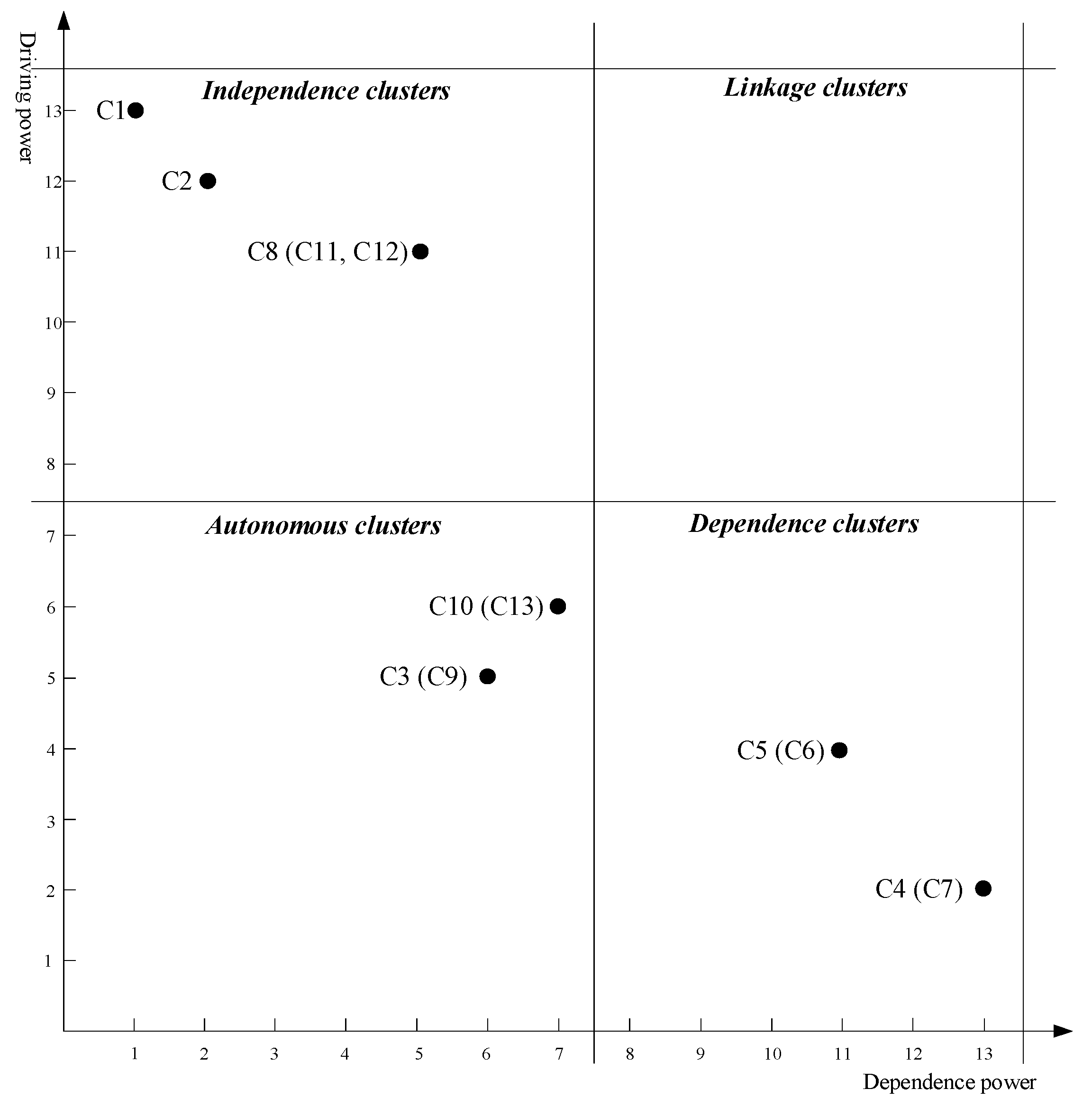

4.1. ISM Results Analysis

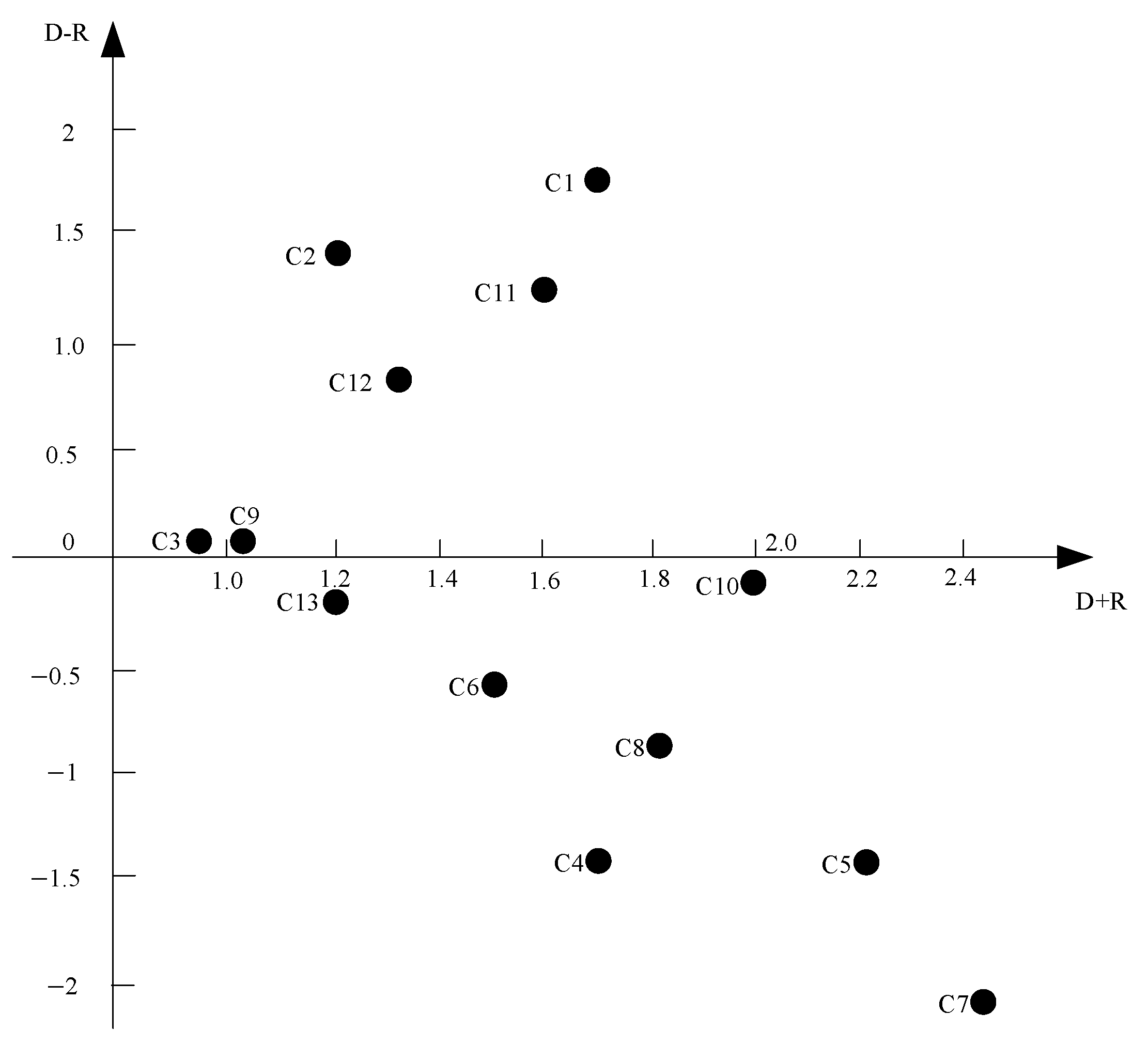

4.2. DEMATEL Results Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, H.; Xiong, W.; Wu, G.; Zhu, D. Public-private partnership in Public Administration discipline: A literature review. Public Manag. Rev. 2018, 20, 293–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppe, E.I.; Schmitz, P.W. Public-private partnerships versus traditional procurement: Innovation incentives and information gathering. Rand. J. Econ. 2013, 44, 56–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casady, C.B.; Eriksson, K.; Levitt, R.E.; Scott, W.R. (Re) defining public-private partnerships (PPPs) in the new public governance (NPG) paradigm: An institutional maturity perspective. Public Manag. Rev. 2020, 22, 161–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.X.; Clegg, S.; Pollack, J. Topic: Power relations in the finance of infrastructure public-private partnership projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2022, 40, 725–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshun, B.T.B.; Chan, A.P.C.; Osei-Kyei, R. Conceptualizing a win-win scenario in public-private partnerships: Evidence from a systematic literature review. Eng. Constr. Arch. Manag. 2021, 28, 2712–2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delhi, V.S.K.; Mahalingam, A. Relating Institutions and Governance Strategies to Project Outcomes: Study on Public-Private Partnerships in Infrastructure Projects in India. J. Manag. Eng. 2020, 36, 04020076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Private Participation in Infrastructure Database; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Dewulf, G.; Garvin, M.J. Responsive governance in PPP projects to manage uncertainty. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2019, 38, 383–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Yu, Y.; Jin, L.; Feng, Z. Early termination compensation under demand uncertainty in public-private partnership projects. Int. J. Strateg. Prop. Manag. 2018, 22, 532–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, W.; Wang, H.; Casady, C.B.; Han, Y. The Impact of Renegotiations on Public Values in Public-Private Partnerships: A Delphi Survey in China. J. Manag. Eng. 2022, 38, 04022040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Jiang, J.; Martek, I.; Jiang, W. Critical risk management strategies for the operation of public-private partnerships: A vulnerability perspective of infrastructure projects. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2024; ahead of print. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.; Li, J.; Wang, D.; Liu, H.; Wu, G.; Yuan, J. Public-private partnerships: A collaborative framework for ensuring project sustainable operations. Eng. Constr. Arch. Manag. 2024, 31, 264–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, W.; Chen, B.; Wang, H.; Zhu, D. Transaction Hazards and Governance Mechanisms in Public-Private Partnerships: A Comparative Study of Two Cases. Public Perform. Manag. 2019, 42, 1279–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, R.; Su, Z. Key Success Factors for Export Structure Optimization in East Asian Countries Through Global Value Chain (GVC) Reorganization. Systems 2025, 13, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iao-Jorgensen, J. Antecedents to bounce forward: A case study tracing the resilience of inter-organisational projects in the face of disruptions. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2023, 41, 102440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, N. The effects of emerging digital technologies on construction project resilience: The mediating role of relational governance. Build. Res. Inf. 2025, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Lim, H.W.; Fang, D. The roles of partnering and boundary activities on project resilience under disruptions. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2024, 30, 391–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yang, X.; Zhu, F.; Klakegg, O.J. How Governance of Interorganizational Projects Develops Resilience: Mediating Role of Resource Reconfiguration. J. Manag. Eng. 2023, 39, 04022076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, F.; Bogus, S.M. Resilience Criteria for Project Delivery Processes: An Exploratory Analysis for Highway Project Development. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2021, 147, 04021140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.; Yang, Q.; Wang, Q.; Jiang, B. Measuring the system resilience of project portfolio network considering risk propagation. Ann. Oper. Res. 2024, 340, 693–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ampratwum, G.; Osei-Kyei, R.; Tam, V.W.Y. Exploring the concept of public-private partnership in building critical infrastructure resilience against unexpected events: A systematic review. Int. J. Crit. Infrastruct. Prot. 2022, 39, 100556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, S.; Zhang, X. Socioeconomic, Macroeconomic, and Sociopolitical Issues in Water PPP Failures. J. Manag. Eng. 2021, 37, 04021047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ali Soomro, M. Failure Path Analysis with Respect to Private Sector Partners in Transportation Public-Private Partnerships. J. Manag. Eng. 2016, 32, 04015031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Sun, J.; Li, F. Influencing Factors of Early Termination for PPP Projects Based on Multicase Grounded Theory. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2022, 148, 04022120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabus, A.F.E. World Problems, an Invitation to Further Thought Within the Framework of DEMATEL; Battelle Geneva Research Center: Geneva, Switzerland, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Froud, J. The Private Finance Initiative: Risk, uncertainty and the state. Account. Organ. Soc. 2003, 28, 567–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, W.; Kumaraswamy, M.; Chung, J.; Wong, J. Identifying the critical success factors for relationship management in PPP projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2014, 32, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osei-Kyei, R.; Chan, A.P.C. Review of studies on the Critical Success Factors for Public-Private Partnership (PPP) projects from 1990 to 2013. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2015, 33, 1335–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, C.O.; Marques, R.C. Flexible contracts to cope with uncertainty in public-private partnerships. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2013, 31, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Wang, H.; Zhang, K. The dynamics of changes in PPP projects—A meta-case analysis approach. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2022, 40, 727–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharafi, A.; Amalnick, M.S.; Taleizadeh, A.A. Outcome of Financial Conflicts in the Operation Phase of Public-Private Partnership Contracts. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2021, 147, 04021047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, Y.; Xiong, W.; Song, J. The moderating role of governance environment on the relationship between risk allocation and private investment in PPP markets: Evidence from developing countries. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2019, 37, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Gong, Z.; Liu, Y.; Thomson, C. The influence of governance on the implementation of Public-Private Partnerships in the United Kingdom and China: A systematic comparison. Util. Policy 2020, 64, 101059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, G.; Beck, M. Stakeholder engagement and the future of Irish public-private partnerships. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2022, 88, 843–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soomro, M.A.; Li, Y.; Han, Y. Socioeconomic and Political Issues in Transportation Public-Private Partnership Failures. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2020, 69, 2073–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Liu, H.; Sun, Y.; Song, L. Contextual recipes for adopting private control and trust in public-private partnership governance. Public Adm. 2023, 101, 884–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, J.; Sanchez-Silva, M. Improving decision-making in maintenance policies and contract specifications for infrastructure projects. Struct. Infrastruct. Eng. 2019, 15, 1087–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budayan, C. Evaluation of Delay Causes for BOT Projects Based on Perceptions of Different Stakeholders in Turkey. J. Manag. Eng. 2019, 35, 04018057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maqbool, R.; Sridhar, H. Governing Public-Private Partnerships of Sustainable Construction Projects in An Opportunistic Setting. Proj. Manag. J. 2024, 55, 86–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanem, M.; Ghaley, M. Building a framework for a resilience-based public private partnership. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2024, 31, 100849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasudevan, V.; Prakash, P.; Sahu, B. Options Framework and Valuation of Highway Infrastructure under Real and Financial Uncertainties. J. Infrastruct. Syst. 2018, 24, 04018014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirel, H.C.; Leendertse, W.; Volker, L. Mechanisms for protecting returns on private investments in public infrastructure projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2022, 40, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Zhang, Z.; Song, J. Profit Allocation and Subsidy Mechanism for Public-Private Partnership Toll Road Projects. J. Manag. Eng. 2020, 36, 04020011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazher, K.M.; Chan, A.P.C.; Zahoor, H.; Khan, M.I.; Ameyaw, E.E. Fuzzy Integral-Based Risk-Assessment Approach for Public-Private Partnership Infrastructure Projects. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2018, 144, 04018111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundararajan, S.K.; Tseng, C. Managing Project Performance Risks under Uncertainty: Using a Dynamic Capital Structure Approach in Infrastructure Project Financing. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2017, 143, 04017046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Xiahou, X.; Li, K.; Li, Q.; Hu, X. Research on the Relationship Between Flexible Contract Term Setting Method and Setting Effect of Environmental Protection PPP Project. Eng. Manag. J. 2023, 35, 272–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingues, S.; Zlatkovic, D. Renegotiating PPP Contracts: Reinforcing the ‘P’ in Partnership. Transp. Rev. 2015, 35, 204–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Pi, C. Real-Option Valuation of Build- Operate-Transfer Infrastructure Projects under Performance Bonding. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2014, 140, 04013068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, M.; Mufti, N.A.; Mubin, S.; Saleem, M.Q.; Zahoor, S.; Ullah, S. Identification of Various Execution Modes and Their Respective Risks for Public-Private Partnership (PPP) Infrastructure Projects. Buildings 2023, 13, 1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Q. Financial viability analysis and capital structure optimization in privatized public infrastructure projects. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2005, 131, 656–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D.K.; Cui, Q.; Chen, L.; Lindly, J.K. Balancing Private and Public Interests in Public-Private Partnership Contracts Through Optimization of Equity Capital Structure. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2010, 2151, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akomea-Frimpong, I.; Jin, X.; Osei-Kyei, R. Mitigating Financial Risks in Sustainable Public-Private Partnership Infrastructure Projects: A Quantitative Analysis. Systems 2024, 12, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House, S. Responsive regulation for water PPP: Balancing commitment and adaptability in the face of uncertainty. Policy Soc 2016, 35, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, R.; Wu, P.; Haershan, M. Pre-contractual relational governance for public-private partnerships: How can ex-ante relational governance help formal contracting in smart city outsourcing projects? Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2023, 89, 112–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonara, N.; Pellegrino, R. The role of public private partnerships in fostering innovation. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2020, 38, 140–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Wang, W.; Gao, X.; Hu, M.; Jiang, H. Sustainable Operations: A Systematic Operational Performance Evaluation Framework for Public-Private Partnership Transportation Infrastructure Projects. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, R.; Sakhrani, V. Appropriating the Value of Flexibility in PPP Megaproject Design. J. Manag. Eng. 2020, 36, 05020010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warfield, J.N. Toward interpretation of complex structural models. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. SMC 1974, 4, 405–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Liang, Y.; Jiang, H.; Gao, T. Research on the Coupled Relationship of Factors Influencing Construction Workers’ Unsafe Behaviors: A Hybrid DEMATEL-ISM-MICMAC Approach. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2023, 2023, 5570547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valmohammadi, C.; Dashti, S. Using interpretive structural modeling and fuzzy analytical process to identify and prioritize the interactive barriers of e-commerce implementation. Inf. Manag. 2016, 53, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindan, K.; Chaudhuri, A. Interrelationships of risks faced by third party logistics service providers: A DEMATEL based approach. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2016, 90, 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jassbi, J.; Mohamadnejad, F.; Nasrollahzadeh, H. A Fuzzy DEMATEL framework for modeling cause and effect relationships of strategy map. Expert Syst. Appl. 2011, 38, 5967–5973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Shou, Y.; Ding, R.; Sun, T.; Zho, Q. Governing local sourcing practices of overseas projects for the Belt and Road Initiative: A framework and evaluation. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2019, 126, 212–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimensions and Categories | Descriptions | Themes | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| D1—Institutional factors | |||

| C1—Regulatory and accountability | Systematically monitor and enforce accountability for compliance, performance | C1.1—Strategic supervision and monitoring | [11,33] |

| C1.2—Transparency management | [13,34] | ||

| C2—Government effectiveness | The comprehensive ability of government agencies to ensure project objectives | C2.1—Existence of sound investment environment | [35,36] |

| C2.2—Defined roles and responsibilities | [21] | ||

| C3—Clear legal framework | Effectively maintain a stable legal and institutional system | C3.1—Policy stability | [32,37] |

| C3.2—Procedural fairness | [21] | ||

| D2—Organizational factors | |||

| C4—Cross- organizational collaboration | Integrating multiple organizational resources, capabilities, and stakeholders | C4.1—Special purpose vehicle team | [4,8] |

| C4.2—Professional consulting agency | [38] | ||

| C4.3—Public participation | [13,21] | ||

| C5—Strategic alliance | Strategic partnership between public and private sectors based on deep collaboration | C5.1—Mutual trust | [36,39] |

| C5.2—Long-term cooperation | [40] | ||

| C5.3—Common goal and shared understanding | [21] | ||

| C6—Private financing stability | The private sector continues to provide funds steadily during the project cycle | C6.1—Selecting multiple financial institutions or financial services | [36,41] |

| C6.2—Purchasing insurance | [35] | ||

| C6.3—Asset portfolio diversification | [42] | ||

| D3—Contractual factors | |||

| C7—Risk allocation and transfer | Reasonably allocate and transfer various risks that may be faced in the process of project implementation | C7.1—Fair/equitable risk sharing or allocation | [11,43] |

| C7.2—Risk reappraisal mechanism | [43,44] | ||

| C7.3—Effective risk allocation and transfer protocols | [8,45] | ||

| C8—Flexible contract | A contract that presupposes an adaptive clause and gives the parties to the contract the right and obligation to adjust under specific conditions | C8.1—Early termination after breach of contract | [9,29] |

| C8.2—Mechanism for renegotiation arrangements | [10,46] | ||

| C8.3—Procedures for resolving claims and disputes | [31,47] | ||

| C8.4—Clear contract change procedure | [30,35] | ||

| C9—Financial planning design | Systematic and forward-looking financial planning for the whole life cycle of the project | C9.1—Equitable revenue guarantee structure | [48,49] |

| C9.2—Optimum financial computation | [43,50] | ||

| C9.3—Strategic financial planning and package | [41,51] | ||

| D4—Managerial factors | |||

| C10—Long-term relationship management | A partnership of sustainability, collaboration, and mutual trust throughout the life cycle of the project | C10.1—Long-term commitment | [52,53] |

| C10.2—Frequent interactions or communication | [21,47] | ||

| C10.3—Strategic conflict resolution and co-ordination | [54] | ||

| C11—Whole life-cycle assessment | Evaluate and manage the economic, technical, social, and environmental values of the project from planning to handover | C11.1—Value for money assessment | [33,55] |

| C11.2—Service quality assessment | [56] | ||

| C11.3—Operational performance assessment | [12,33] | ||

| C12—Management capability development | Systematically integrate resources and improve team knowledge and skills | C12.1—Technical innovation development | [21] |

| C12.2—Development of integrative dynamic capabilities | [5,13] | ||

| C13—Information and resource sharing | Mechanism for systematic sharing of knowledge, resources, and benefits | C13.1—Knowledge sharing | [6,8] |

| C13.2—Exchange of resources | [6,21] | ||

| C13.3—Sharing profit-making for the project | [57] | ||

| ID | Role | Gender | Role/Position | Experience |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. 1 | Government | Male | Officer | Over 10 years |

| No. 2 | Government | Male | Vice Director | Over 20 years |

| No. 3 | Private sector | Female | Manager | Over 15 years |

| No. 4 | Private sector | Male | Engineer | Over 20 years |

| No. 5 | Private sector | Male | Manager | Over 15 years |

| No. 6 | Consultant | Female | Professor | Over 15 years |

| No. 7 | Consultant | Male | Professor | Over 20 years |

| No. 8 | Consultant | Male | Manager | Over 15 years |

| No. 9 | Financial institution | Female | Manager | Over 15 years |

| No. 10 | Financial institution | Male | Stuff | Over 10 years |

| Factors | Governance Factors | D | R | D + R | D − R | Rank | Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | Regulatory and accountability | 1.734 | 0 | 1.734 | 1.734 | 6 | Cause |

| C2 | Government effectiveness | 1.349 | 0.08 | 1.429 | 1.269 | 9 | Cause |

| C3 | Clear legal framework | 0.457 | 0.388 | 0.845 | 0.064 | 13 | Cause |

| C4 | Cross-organizational collaboration | 0.175 | 1.594 | 1.769 | −1.419 | 5 | Effect |

| C5 | Strategic alliance | 0.444 | 1.836 | 2.280 | −1.398 | 2 | Effect |

| C6 | Private financing stability | 0.456 | 1.114 | 1.570 | −0.657 | 8 | Effect |

| C7 | Risk allocation and transfer | 0.094 | 2.371 | 2.465 | −2.277 | 1 | Effect |

| C8 | Flexible contract | 1.386 | 0.497 | 1.883 | 0.888 | 4 | Cause |

| C9 | Financial planning design | 0.529 | 0.482 | 1.010 | 0.047 | 12 | Cause |

| C10 | Long-term relationship management | 0.906 | 1.067 | 1.974 | −0.161 | 3 | Effect |

| C11 | Whole life-cycle assessment | 1.421 | 0.193 | 1.614 | 1.228 | 7 | Cause |

| C12 | Management capability development | 1.067 | 0.251 | 1.317 | 0.816 | 10 | Cause |

| C13 | Information and resource sharing | 0.537 | 0.680 | 1.217 | −0.142 | 11 | Effect |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, Z.; Wang, N.; Du, Q. The Governance of PPP Project Resilience: A Hybrid DMATEL-ISM Approach. Systems 2025, 13, 277. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13040277

Liu Z, Wang N, Du Q. The Governance of PPP Project Resilience: A Hybrid DMATEL-ISM Approach. Systems. 2025; 13(4):277. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13040277

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Zhankun, Nannan Wang, and Qiushi Du. 2025. "The Governance of PPP Project Resilience: A Hybrid DMATEL-ISM Approach" Systems 13, no. 4: 277. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13040277

APA StyleLiu, Z., Wang, N., & Du, Q. (2025). The Governance of PPP Project Resilience: A Hybrid DMATEL-ISM Approach. Systems, 13(4), 277. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13040277