Building a Resilient Organization Through Informal Networks: Examining the Role of Individual, Structural, and Attitudinal Factors in Advice-Seeking Tie Formation

Abstract

1. Introduction

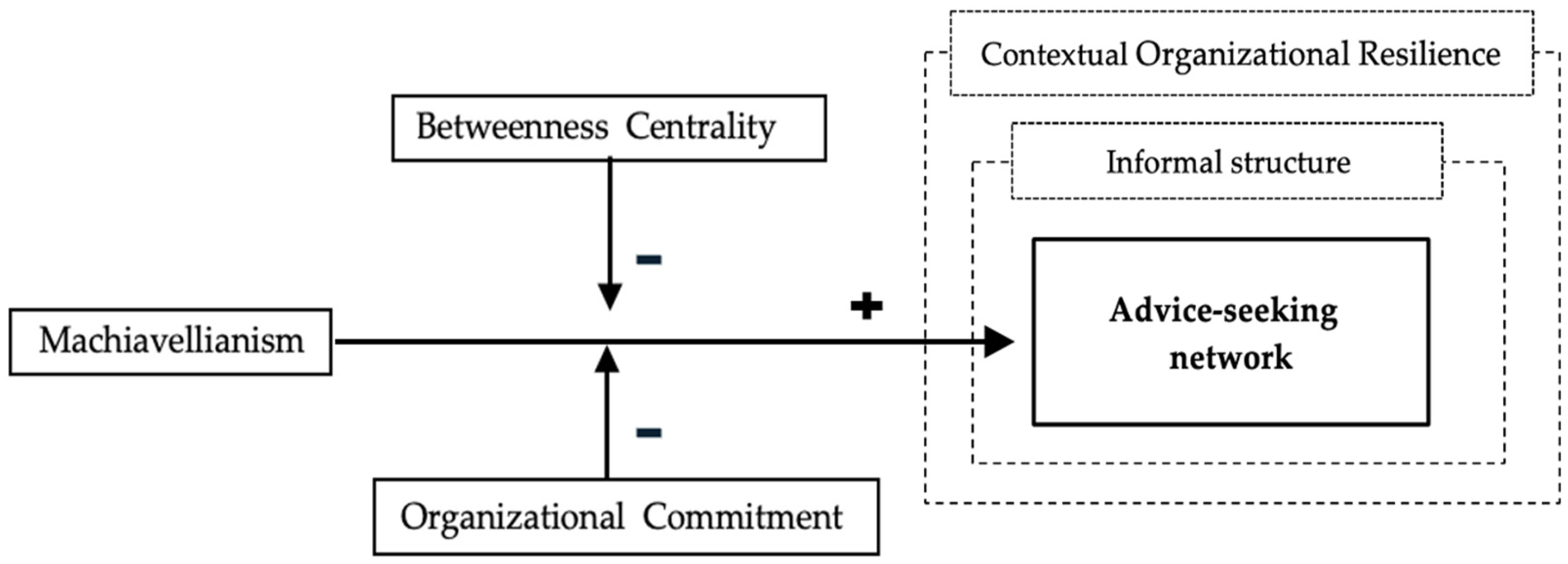

2. Hypothesis Development

2.1. Informal Advice Network as a Crucial System of the Company

2.2. Machiavellianism and Advice-Seeking Ties

2.3. Employees’ Network Positions: Betweenness Centrality in Advice Exchange Network

2.4. Employee’s Job Attitude Toward Their Organization: Organizational Commitment

3. Methods

3.1. Data

3.2. Exponential Random Graph Modeling

3.3. Measurement

3.3.1. Dependent Variable

3.3.2. Independent Variables

3.3.3. Control Variables

4. Results

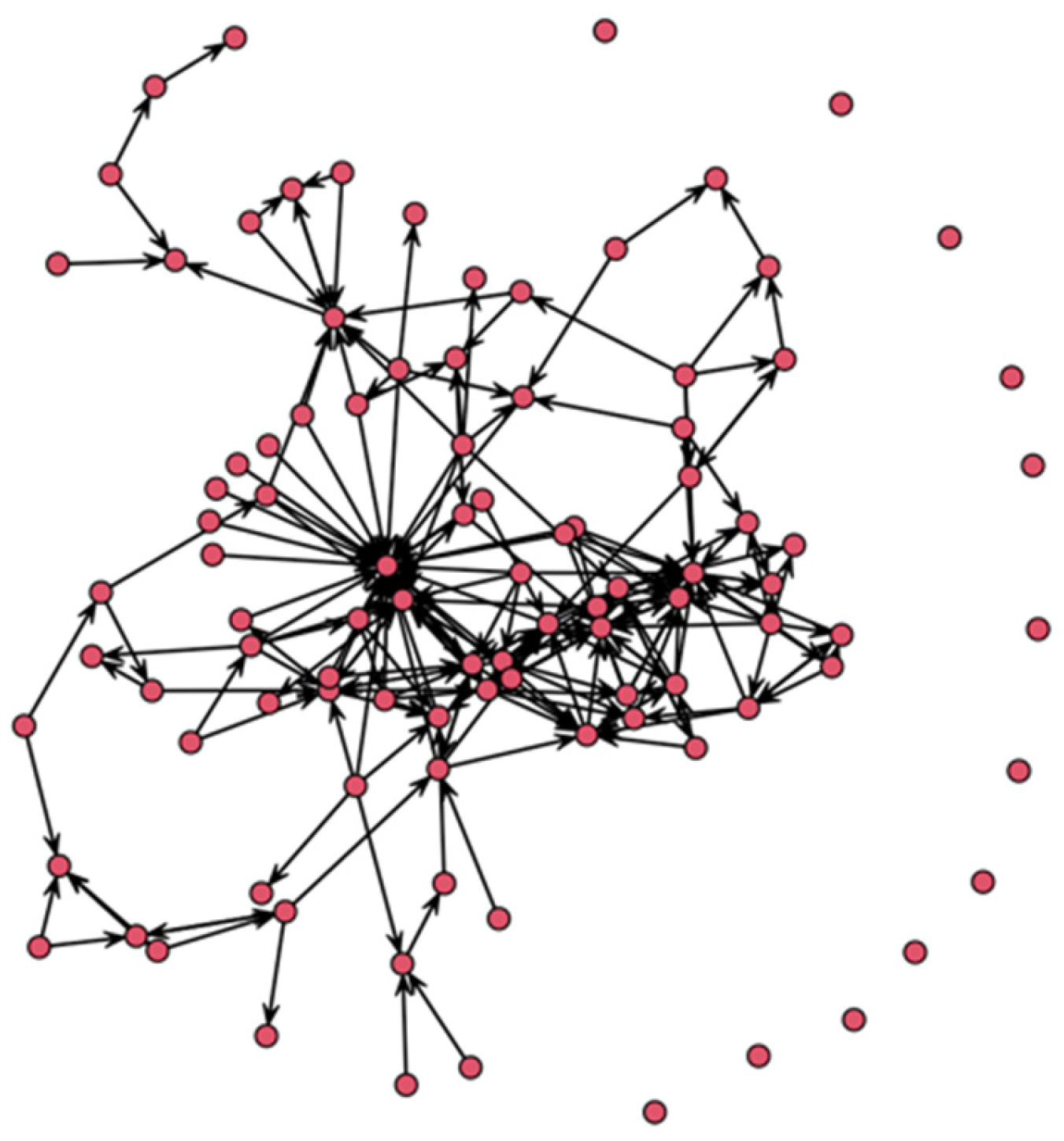

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Estimation

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Boin, A.; Van Eeten, M.J. The resilient organization. Public Manag. Rev. 2013, 15, 429–445. [Google Scholar]

- Nyaupane, G.P.; Prayag, G.; Godwyll, J.; White, D. Toward a resilient organization: Analysis of employee skills and organization adaptive traits. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 658–677. [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira Teixeira, E.; Werther, W.B., Jr. Resilience: Continuous renewal of competitive advantages. Bus. Horiz. 2013, 56, 333–342. [Google Scholar]

- Annarelli, A.; Nonino, F. Strategic and operational management of organizational resilience: Current state of research and future directions. Omega 2016, 62, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Linnenluecke, M.K.; Griffiths, A.; Winn, M. Extreme weather events and the critical importance of anticipatory adaptation and organizational resilience in responding to impacts. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2012, 21, 17–32. [Google Scholar]

- Burnard, K.; Bhamra, R. Organisational resilience: Development of a conceptual framework for organisational responses. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2011, 49, 5581–5599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutcliffe, K. Organizing for resilience. In Positive Organizational Scholarship: Foundations of a New Discipline; Cameron, K.S., Dutton, J.E., Quinn, R.E., Eds.; Berrett-Koehler: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2003; pp. 94–110. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn, W.A.; Barton, M.A.; Fisher, C.M.; Heaphy, E.D.; Reid, E.M.; Rouse, E.D. The geography of strain: Organizational resilience as a function of intergroup relations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2018, 43, 509–529. [Google Scholar]

- Reason, J. Managing the Risks of Organizational Accidents; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; ISBN 9781315543543. [Google Scholar]

- Catino, M.; Patriotta, G. Learning from errors: Cognition, emotions and safety culture in the Italian air force. Organ. Stud. 2013, 34, 437–467. [Google Scholar]

- Madni, A.M.; Jackson, S. Towards a conceptual framework for resilience engineering. IEEE Syst. J. 2009, 3, 181–191. [Google Scholar]

- Ciasullo, M.V.; Chiarini, A.; Palumbo, R. Mastering the interplay of organizational resilience and sustainability: Insights from a hybrid literature review. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 1418–1446. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, Y.-L.; Cai, W. Enhancing post-COVID-19 work resilience in hospitality: A micro-level crisis management framework. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2023, 23, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yin, J. Stakeholder relationships and organizational resilience. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2020, 16, 986–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lengnick-Hall, C.A.; Beck, T.E.; Lengnick-Hall, M.L. Developing a capacity for organizational resilience through strategic human resource management. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2011, 21, 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xue, Y.; Yang, J. Can proactive boundary-spanning search enhance green innovation? The mediating role of organizational resilience. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 1981–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, T.A.; Gruber, D.A.; Sutcliffe, K.M.; Shepherd, D.A.; Zhao, E.Y. Organizational response to adversity: Fusing crisis management and resilience research streams. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2017, 11, 733–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollnagel, E.; Woods, D.D.; Leveson, N. Resilience Engineering: Concepts and Precepts; Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.: Farnham, UK, 2006; ISBN 9780754681366. [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Vegt, G.S.; Essens, P.; Wahlström, M.; George, G. Managing risk and resilience. Acad. Manag. J. 2015, 58, 971–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krackhardt, D.; Hanson, J.R. Informal networks: The company behind the chart. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1993, 71, 104–111. [Google Scholar]

- Cross, R.L.; Parker, A. The Hidden Power of Social Networks: Understanding How Work Really Gets Done in Organizations; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Donelli, C.C.; Fanelli, S.; Zangrandi, A.; Elefanti, M. Disruptive crisis management: Lessons from managing a hospital during the COVID-19 pandemic. Manag. Decis. 2022, 60, 66–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasic, J.; Amir, S.; Tan, J.; Khader, M. A multilevel framework to enhance organizational resilience. J. Risk Res. 2020, 23, 713–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lee, H.W.; Chung, G.H. Organizational resilience: Leadership, operational and individual responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2024, 37, 92–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, R.S. The social structure of competition. In Structural Holes: The Social Structure of Competition; Harvard University Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kilduff, M.; Brass, D.J. Organizational social network research: Core ideas and key debates. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2010, 4, 317–357. [Google Scholar]

- Zagenczyk, T.J.; Gibney, R.; Murrell, A.J.; Boss, S.R. Friends don’t make friends good citizens, but advisors do. Group Organ. Manag. 2008, 33, 760–780. [Google Scholar]

- Zagenczyk, T.J.; Murrell, A.J. It is better to receive than to give: Advice network effects on job and work-unit attachment. J. Bus. Psychol. 2009, 24, 139–152. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons, D.E. Friendship and advice networks in the context of changing professional values. Adm. Sci. Q. 2004, 49, 238–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, D.; Kahn, R. The social psychology of organizations. In Organizational Behavior 2; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; pp. 152–168. [Google Scholar]

- Greeley, A.M. The Friendship Game; Doubleday Books: New York, NY, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, J.D.; Weigert, A. Trust as social reality. Soc. Forces 1985, 63, 967–985. [Google Scholar]

- Umphress, E.E.; Labianca, G.; Brass, D.J.; Kass, E.; Scholten, L. The role of instrumental and expressive social ties in employees’ perceptions of organizational justice. Organ. Sci. 2003, 14, 738–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, M.H.; Oh, H.S. Human Network and Business Management; Kyungmunsa: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2005; pp. 54–56. ISBN 9788976332790. [Google Scholar]

- Weick, K.E. The social psychology of organizing. Management 2015, 18, 189. [Google Scholar]

- Mirc, N.; Parker, A. If you do not know who knows what: Advice seeking under changing conditions of uncertainty after an acquisition. Soc. Netw. 2020, 61, 53–66. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, M.; Krause, J. Why personality differences matter for social functioning and social structure. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2014, 29, 306–308. [Google Scholar]

- Ilany, A.; Akçay, E. Personality and social networks: A generative model approach. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2016, 56, 1197–1205. [Google Scholar]

- Brissette, I.; Scheier, M.F.; Carver, C.S. The role of optimism in social network development, coping, and psychological adjustment during a life transition. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 82, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilduff, M. Social Networks and Organizations; Sage: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, R.; Landis, B.; Zhang, Z.; Anderson, M.H.; Shaw, J.D.; Kilduff, M. Integrating personality and social networks: A meta-analysis of personality, network position, and work outcomes in organizations. Organ. Sci. 2015, 26, 1243–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battistoni, E.; Colladon, A.F. Personality correlates of key roles in informal advice networks. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2014, 34, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selfhout, M.; Burk, W.; Branje, S.; Denissen, J.; Van Aken, M.; Meeus, W. Emerging late adolescent friendship networks and Big Five personality traits: A social network approach. J. Personal. 2010, 78, 509–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehrli, S. Personality on Social Network Sites: An Application of the Five Factor Model; Working Paper No. 7; ETH Sociology: Zurich, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Krause, J.; James, R.; Croft, D. Personality in the context of social networks. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2010, 365, 4099–4106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepri, B.; Staiano, J.; Shmueli, E.; Pianesi, F.; Pentland, A. The role of personality in shaping social networks and mediating behavioral change. User Model. User-Adapt. Interact. 2016, 26, 143–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Pan, Y.; Guo, B. The influence of personality traits and social networks on the self-disclosure behavior of social network site users. Internet Res. 2016, 26, 566–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landis, B. Personality and social networks in organizations: A review and future directions. J. Organ. Behav. 2016, 37, S107–S121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pornsakulvanich, V. Personality, attitudes, social influences, and social networking site usage predicting online social support. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 76, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasselli, S.; Kilduff, M. Network agency. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2021, 15, 68–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shipilov, A.; Labianca, G.; Kalnysh, V.; Kalnysh, Y. Network-building behavioral tendencies, range, and promotion speed. Soc. Netw. 2014, 39, 71–83. [Google Scholar]

- Chandler, J.A.; Petrenko, O.V.; Hill, A.D.; Hayes, N. CEO Machiavellianism and strategic alliances in family firms. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2021, 34, 93–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christie, R.; Geis, F.L. Studies in Machiavellianism; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, P.R. Attitude, Machiavellianism and the rationalization of misreporting. Account. Organ. Soc. 2012, 37, 242–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, J.A.; Dan O’Hair, H. Machiavellians’ motives in organizational citizenship behavior. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 2007, 35, 246–267. [Google Scholar]

- Dahling, J.J.; Whitaker, B.G.; Levy, P.E. The development and validation of a new Machiavellianism scale. J. Manag. 2009, 35, 219–257. [Google Scholar]

- Rauthmann, J.F. The Dark Triad and interpersonal perception: Similarities and differences in the social consequences of narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2012, 3, 487–496. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski, C.M.; Kwiatkowska, K.; Kwiatkowska, M.M.; Ponikiewska, K.; Rogoza, R.; Schermer, J.A. The Dark Triad traits and intelligence: Machiavellians are bright, and narcissists and psychopaths are ordinary. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2018, 135, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Bereczkei, T. Machiavellian intelligence hypothesis revisited: What evolved cognitive and social skills may underlie human manipulation. Evol. Behav. Sci. 2018, 12, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Judge, T.A.; Piccolo, R.F.; Kosalka, T. The bright and dark sides of leader traits: A review and theoretical extension of the leader trait paradigm. Leadersh. Q. 2009, 20, 855–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Li, Z. Seeking or giving help? Linkages between the Dark Triad traits and adolescents’ help seeking and giving orientations: The role of zero-sum mindset. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2025, 236, 113031. [Google Scholar]

- Recendes, T.; Aime, F.; Hill, A.D.; Petrenko, O.V. Bargaining your way to success: The effect of Machiavellian chief executive officers on firm costs. Strateg. Manag. J. 2022, 43, 2012–2041. [Google Scholar]

- Jonason, P.K.; Slomski, S.; Partyka, J. The Dark Triad at work: How toxic employees get their way. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2012, 52, 449–453. [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson, S.B. Personality and organizational destructiveness: Fact, fiction, and fable. In Developmental Science and the Holistic Approach; Routledge: London, UK, 2000; pp. 309–324. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, S.R.; Bandelli, A.C.; Spector, P.E.; Borman, W.C.; Nelson, C.E.; Penney, L.M. Re-examining Machiavelli: A three-dimensional model of Machiavellianism in the workplace. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 40, 1868–1896. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, H.; Wang, L.; Jin, X. Leader’s Machiavellianism and employees’ counterproductive work behavior: Testing a moderated mediation model. Front. Psychol. 2024, 14, 1283509. [Google Scholar]

- O’Boyle, E.H.; Forsyth, D.R.; Banks, G.C.; Story, P.A.; White, C.D. A meta-analytic test of redundancy and relative importance of the dark triad and five-factor model of personality. J. Personal. 2015, 83, 644–664. [Google Scholar]

- Castille, C.M.; Buckner, J.E.; Thoroughgood, C.N. Prosocial citizens without a moral compass? Examining the relationship between Machiavellianism and unethical pro-organizational behavior. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 149, 919–930. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M.B.; Hill, A.D.; Wallace, J.C.; Recendes, T.; Judge, T.A. Upsides to dark and downsides to bright personality: A multidomain review and future research agenda. J. Manag. 2018, 44, 191–217. [Google Scholar]

- Burt, R.S. Structural holes. In Social Stratification; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 659–663. ISBN 9780429494642. [Google Scholar]

- Kantek, F.; Yesilbas, H.; Yildirim, N.; Dundar Kavakli, B. Social network analysis: Understanding nurses’ advice-seeking interactions. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2023, 70, 322–328. [Google Scholar]

- Creswick, N.; Westbrook, J.I. Social network analysis of medication advice-seeking interactions among staff in an Australian hospital. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2010, 79, e116–e125. [Google Scholar]

- Uppal, N. How Machiavellianism engenders impression management motives: The role of social astuteness and networking ability. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2021, 168, 110314. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, W.; Zhan, T.; Geng, Y.; Shi, Y.; Hu, W.; Ye, B. Social appearance anxiety among the dark tetrad and self-concealment. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 4667. [Google Scholar]

- Toebben, L.; Casper, A.; Wehrt, W.; Sonnentag, S. Reasons for interruptions at work: Illuminating the perspective of the interrupter. J. Organ. Behav. 2025, 46, 24–42. [Google Scholar]

- Leroy, S.; Glomb, T.M. Tasks interrupted: How anticipating time pressure on resumption of an interrupted task causes attention residue and low performance on interrupting tasks and how a “ready-to-resume” plan mitigates the effects. Organ. Sci. 2018, 29, 380–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Zhao, X.; Shen, H. The concept, influence, and mechanism of human work interruptions based on the grounded theory. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1044233. [Google Scholar]

- Baethge, A.; Rigotti, T. Interruptions to workflow: Their relationship with irritation and satisfaction with performance, and the mediating roles of time pressure and mental demands. Work Stress 2013, 27, 43–63. [Google Scholar]

- Perlow, L.A. The time famine: Toward a sociology of work time. Adm. Sci. Q. 1999, 44, 57–81. [Google Scholar]

- Puranik, H.; Koopman, J.; Vough, H.C. Pardon the interruption: An integrative review and future research agenda for research on work interruptions. J. Manag. 2020, 46, 806–842. [Google Scholar]

- Ok, A.B.; Vandenberghe, C. Organizational and career-oriented commitment and employee development behaviors. J. Manag. Psychol. 2016, 31, 930–945. [Google Scholar]

- Sturges, J.; Guest, D.; Conway, N.; Davey, K.M. A longitudinal study of the relationship between career management and organizational commitment among graduates in the first ten years at work. J. Organ. Behav. Int. J. Ind. Occup. Organ. Psychol. Behav. 2002, 23, 731–748. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, J.-M.; Rai, A.; Rigdon, E. Predictive validity and formative measurement in structural equation modeling: Embracing practical relevance. In Proceedings of the 2013 International Conference on Information Systems, Milan, Italy, 15–18 December 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Olfat, M.; Rezvani, A.; Khosravi, P.; Shokouhyar, S.; Sedaghat, A. The influence of organisational commitment on employees’ work-related use of online social networks: The mediating role of constructive voice. Int. J. Manpow. 2020, 41, 168–183. [Google Scholar]

- Yahaya, R.; Ebrahim, F. Leadership styles and organizational commitment: Literature review. J. Manag. Dev. 2016, 35, 190–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, B. Building organizational commitment: The socialization of managers in work organizations. Adm. Sci. Q. 1974, 19, 533–546. [Google Scholar]

- Mowday, R.T.; Steers, R.M.; Porter, L.W. The measurement of organizational commitment. J. Vocat. Behav. 1979, 14, 224–247. [Google Scholar]

- Shumate, M.; Palazzolo, E.T. Exponential random graph (p*) models as a method for social network analysis in communication research. Commun. Methods Meas. 2010, 4, 341–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titi Amayah, A. Determinants of knowledge sharing in a public sector organization. J. Knowl. Manag. 2013, 17, 454–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snijders, T.A. Statistical models for social networks. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2011, 37, 131–153. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.; Robins, G.; Pattison, P.; Lazega, E. Exponential random graph models for multilevel networks. Soc. Netw. 2013, 35, 96–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matous, P.; Wang, P. External exposure, boundary-spanning, and opinion leadership in remote communities: A network experiment. Soc. Netw. 2019, 56, 10–22. [Google Scholar]

- Lusher, D.; Koskinen, J.; Robins, G. Exponential Random Graph Models for Social Networks: Theory, Methods, and Applications; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Siciliano, M.D. Advice networks in public organizations: The role of structure, internal competition, and individual attributes. Public Adm. Rev. 2015, 75, 548–559. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y. How conversational ties are formed in an online community: A social network analysis of a tweet chat group. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2020, 23, 1463–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Howard, M.; Cox Pahnke, E.; Boeker, W. Understanding network formation in strategy research: Exponential random graph models. Strateg. Manag. J. 2016, 37, 22–44. [Google Scholar]

- Lubbers, M.J.; Snijders, T.A. A comparison of various approaches to the exponential random graph model: A reanalysis of 102 student networks in school classes. Soc. Netw. 2007, 29, 489–507. [Google Scholar]

- Karkavandi, M.A.; Wang, P.; Lusher, D.; Bastian, B.; McKenzie, V.; Robins, G. Perceived friendship network of socially anxious adolescent girls. Soc. Netw. 2022, 68, 330–345. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, L.C. Centrality in social networks: Conceptual clarification. Soc. Netw. Crit. Concepts Sociol. Lond. Routledge 2002, 1, 238–263. [Google Scholar]

- Abbasi, A.; Hossain, L.; Leydesdorff, L. Betweenness centrality as a driver of preferential attachment in the evolution of research collaboration networks. J. Informetr. 2012, 6, 403–412. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Ye, F.; Li, Y.; Chang, C.-T. How will the Chinese Certified Emission Reduction scheme save cost for the national carbon trading system? J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 244, 99–109. [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman, S. Social Network Analysis: Methods and Applications; The Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge: Cambridge, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Gould, R.V. Measures of betweenness in non-symmetric networks. Soc. Netw. 1987, 9, 277–282. [Google Scholar]

- Fields, D.L. Taking the Measure of Work: A Guide to Validated Scales for Organizational Research and Diagnosis; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Block, P. Reciprocity, transitivity, and the mysterious three-cycle. Soc. Netw. 2015, 40, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennecke, J.; Ertug, G.; Elfring, T. Networking fast and slow: The role of speed in tie formation. J. Manag. 2024, 50, 1230–1258. [Google Scholar]

- Mascia, D.; Pallotti, F.; Dandi, R. Determinants of knowledge-sharing networks in primary care. Health Care Manag. Rev. 2018, 43, 104–114. [Google Scholar]

- Tyagi, A.; Gómez-Zará, D.; Contractor, N.S. How do friendship and advice ties emerge? A case study of graduate student social networks. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining (ASONAM), The Hague, The Netherlands, 3–6 August 2020; pp. 578–585. [Google Scholar]

- Agneessens, F.; Trincado-Munoz, F.J.; Koskinen, J. Network formation in organizational settings: Exploring the importance of local social processes and team-level contextual variables in small groups using bayesian hierarchical ERGMs. Soc. Netw. 2024, 77, 104–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, H.; Parent, O. Beyond homophilic dyadic interactions: The impact of network formation on individual outcomes. Stat. Comput. 2023, 33, 43. [Google Scholar]

- Jehn, K.A. A qualitative analysis of conflict types and dimensions in organizational groups. Adm. Sci. Q. 1997, 42, 530–557. [Google Scholar]

- Marineau, J.E.; Hood, A.C.; Labianca, G.J. Multiplex conflict: Examining the effects of overlapping task and relationship conflict on advice seeking in organizations. J. Bus. Psychol. 2018, 33, 595–610. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, B. Determinants of social capital from a network perspective: A case of Sinchon regeneration project using exponential random graph models. Cities 2022, 120, 103419. [Google Scholar]

- Chipidza, W.; Tripp, J.; Akbaripourdibazar, E.; Kim, T. Gender and Racial Homophily in Email Networks and the Moderating Role of Business Unit on Network Structure: Evidence from a Large Financial Services Company. In Proceedings of the AMCIS, Online, 9–13 August 2021. [Google Scholar]

| Count Variables | Counts | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| edges | 223 | 1 | |||||||||||

| mutual | 17 | 0.48 | 1 | ||||||||||

| twopath | 501 | 0.93 | 0.48 | 1 | |||||||||

| nodematch. employment | 106 | 0.71 | 0.37 | 0.66 | 1 | ||||||||

| nodematch. gender | 106 | 0.65 | 0.30 | 0.61 | 0.51 | 1 | |||||||

| nodematch. position | 42 | 0.39 | 0.22 | 0.36 | 0.48 | 0.37 | 1 | ||||||

| absdiff. role ambiguity | 137 | 0.75 | 0.36 | 0.70 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.29 | 1 | |||||

| Continuous Variables | Mean | SD | |||||||||||

| social stress | 2.21 | 0.70 | 0.97 | 0.46 | 0.88 | 0.70 | 0.63 | 0.38 | 0.71 | 1 | |||

| Machiavellianism | 2.27 | 0.28 | 0.04 | −0.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 1 | ||

| betweenness centrality | 26.83 | 63.21 | 0.15 | −0.01 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.08 | −0.01 | 0.11 | 0.17 | 0.00 | 1 | |

| organizational commitment | 3.25 | 0.61 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.03 | −0.03 | −0.01 | −0.05 | −0.02 | −0.08 | −0.16 | 0.11 | 1 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Est. | p Value | Test Stat. | Est. | p Value | Test Stat. | Est. | p Value | Test Stat. | |

| Purely structural | |||||||||

| edges | −2.16 | 0.00 | −0.47 | −2.03 | 0.00 | −0.06 | −1.95 | 0.00 | −1.69 |

| mutual | 2.06 | 0.00 | −1.93 | 2.10 | 0.00 | −0.61 | 2.08 | 0.00 | −1.60 |

| twopath | −0.08 | 0.09 | −0.01 | −0.07 | 0.09 | 0.29 | −0.07 | 0.13 | −1.92 |

| Actor-relation | |||||||||

| nodematch. employment. 1 | 0.49 | 0.00 | −0.61 | 0.52 | 0.00 | −0.85 | 0.51 | 0.00 | −0.91 |

| nodematch. employment. 2 | −0.70 | 0.01 | 0.83 | −0.73 | 0.01 | 0.93 | −0.70 | 0.01 | −1.51 |

| nodematch. gender | −0.09 | 0.49 | 0.26 | −0.10 | 0.43 | 0.14 | −0.10 | 0.45 | 1.75 |

| nodematch. position | 0.04 | 0.83 | −1.51 | 0.05 | 0.80 | −0.41 | 0.02 | 0.89 | −0.27 |

| absdiff. role ambiguity | −0.15 | 0.28 | −1.10 | −0.17 | 0.22 | 1.89 | −0.19 | 0.18 | −0.22 |

| Node’s attribute | |||||||||

| social stress | −0.31 | 0.00 | −0.64 | −0.36 | 0.00 | −0.02 | −0.38 | 0.00 | −1.29 |

| Machiavellianism | 0.93 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.70 | 0.01 | −1.14 | |||

| betweenness centrality | 0.00 | 0.00 | −1.90 | ||||||

| Machiavellianism × betweenness centrality | −0.00 | 0.01 | 0.79 | ||||||

| organizational commitment | −0.16 | 0.17 | −1.51 | ||||||

| Machiavellianism × organizational commitment | −0.92 | 0.04 | −0.04 | ||||||

| AIC | 2065 | 2046 | 2059 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jin, X.; Yang, D.; Sun, W.; Xu, L. Building a Resilient Organization Through Informal Networks: Examining the Role of Individual, Structural, and Attitudinal Factors in Advice-Seeking Tie Formation. Systems 2025, 13, 245. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13040245

Jin X, Yang D, Sun W, Xu L. Building a Resilient Organization Through Informal Networks: Examining the Role of Individual, Structural, and Attitudinal Factors in Advice-Seeking Tie Formation. Systems. 2025; 13(4):245. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13040245

Chicago/Turabian StyleJin, Xiaoyan, Daegyu Yang, Wanlan Sun, and Lian Xu. 2025. "Building a Resilient Organization Through Informal Networks: Examining the Role of Individual, Structural, and Attitudinal Factors in Advice-Seeking Tie Formation" Systems 13, no. 4: 245. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13040245

APA StyleJin, X., Yang, D., Sun, W., & Xu, L. (2025). Building a Resilient Organization Through Informal Networks: Examining the Role of Individual, Structural, and Attitudinal Factors in Advice-Seeking Tie Formation. Systems, 13(4), 245. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13040245