Abstract

The COVID-19 outbreak has currently led to serious social and economic consequences. In poor and developing countries, there are more challenges and barriers to tackling the pandemic. The study’s aim is to propose a hybrid approach to multiple-criteria decision-making (MCDM) models for determining the most efficient intervention strategies. The methodology is a combination between the Best-Worst Model (BWM) and Group Best-Worst Model (GBWM) to estimate the efficiency score of intervention. Based on the background of knowledge, five groups of stakeholders including Academicians, Entrepreneurs, Commons Residents, Social Workers, Health Workers are considered decision-makers (DMs). A set of nine potential strategies was evaluated and prioritized by all DMs. The findings have shown that different groups of stakeholders prioritized differently the importance of criteria due to their interests. In the context of Vietnam, however, the Availability of Health Systems is prioritized as the most important intervention. The results and proposed model of this paper contributed to MCDM literature as well as a good reference to apply practically in many different countries.

1. Introduction

At the end of 2019, an infectious disease which is caused by a novel form of coronavirus appeared in Wuhan (China). Afterward, the disease spread rapidly and became a global pandemic. The World Health Organization (WHO) labeled the form of pneumonia disease as COVID-19 which is caused by the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Corona Virus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) []. The number of infected cases soared to the point of outbreaks in many countries. By 10th May 2022, according to the statistics on worldometers.info, it accounted for about 518 million SARS-CoV-2 infected cases around the world, with about 6.3 million deaths []. The coronavirus COVID-19 is affecting 220 countries and territories of which the USA, India, and Brazil are the three leading nations in the number of infected cases. The COVID-19 pandemic has become the largest crisis since World War II []. Vietnam is not an exception with the alarmingly increasing number of newly infected people. By 18 July 2021, the Vietnamese Government imposed the second complete lockdown throughout the country since the figures reported daily climbed to 3000 cases on average. The rapid spread of COVID-19 can collapse any healthcare system and that is what happened in the USA, Italy, and India. Although the vaccine types were invented in developed countries, variants of the coronavirus have occurred and the number of infections has risen rapidly. In addition, developing or low-income countries have encountered many challenges in approaching the COVID-19 vaccine. The situation could be worsened if governments delay in planning to face the challenges and threats. Nations like Vietnam, therefore, must design other strategies to tackle the spread of the pandemic. Many different intervention strategies have been adopted such as lockdowns, digital surveillance, isolation of infected patients, and widespread testing []. Nevertheless, governments face many difficulties in implementing such interventions. For example, issues related to ethics and privacy arise with the use of digital surveillance to track and monitor mechanisms; or a complete lockdown of the country significantly influences economics or food security for poor people. Greater attention is merited to scientific research studying the relationship between intervention strategies and public health decision-making, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In terms of decision-making studies, the Multi-Criteria Decision-Making method (MCDM) and its applications have become the most common technique, especially in the industrial sector or supply chain management [,]. For example, Wang et al. (2021) applied Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) to evaluate the environmental efficiency across ASEAN nations [] and Wang et al. (2021) used a two-stage hybrid approach of DEA and AHP to select the most optimal Wind Plants in Vietnam []. In terms of tourism, Wang and Nguyen (2022) evaluated the sustainability of hotels using MCDM models []. However, these studies are based on subjective individuals or experts to evaluate the performance efficiency of units (i.e., location, firms, countries, etc.). The authors, hence, found a research gap in the literature on applying MCDM models for group decision-makers. One of the most recent MCDM models is the Best-Worst Method (BWM) introduced by Rezaei (2015) []. The BWM method has some advantages compared to other MCDM models in analytical evaluation and interpretation of human perception with fewer comparisons. It could be developed for group decision-makers. Moreover, the literature on the application of the MCDM models in the public sector is attracted many scholars’ attention. For example, Ozgur (2013) used the AHP model to evaluate and prioritize the pandemic mitigation strategies []; or Lopez and Gumasekaran used the fuzzy logic-based VIKOR to evaluate the H1N1 vaccine in Vellore city of India in 2015 []. Nevertheless, limited research has been conducted to evaluate public health strategies related to the COVID-19 pandemic [].

Therefore, the study aimed to propose a novel model to evaluate and prioritize the identified factors in intervention strategies to handle COVID-19 outbreaks in developing countries. Vietnam was selected as a case study. The research model is a combination of two extended MCDM approaches, namely the Best-Worst Model (BWM) and Group Best-Worst Model (GBWM). In addition, the proposed research framework in this study was expected to fill a research gap in the literature related to the application of MCDM in public health sectors. The findings in the study can be seen as a good reference for decision-makers or policymakers to have a good evaluation of interventions and have better strategies.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Multi-Criteria Decision-Making Model

Decision-making is primarily a complex process that involves various aspects concerned and the existence of differences in perception. It is necessary to have tools and techniques supporting decision-makers to take appropriate strategies in complex contexts. Beginning in the 1950s, Neumann and Morgenstern [] introduced the foundation of modern multi-criteria decision-making methods (MCDM) to minimize or maximize a utility function in the presence of constraints. The MCDM methods have been developed in various models. For example, Charnes (1978) introduced Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) []; Saaty (1980) proposed the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) []; Hwang and Lin (1981) published a study on Group Decision-Making under multi-criteria []; in 2015, one of the most recent MCDM models invented by Rezaei is the Best-Worst multi-criteria decision-making method []. The procedure for running MCDM models includes two basic steps: estimating criteria and ranking of alternatives []. Many different MCDM methods and their applications are implemented to support decision-makers in various fields. (See more in Table 1).

Table 1.

Literature Review of MCDM Application.

In reviewing previous literature, the lack of studies applying the Best-Worst Method in health public decision sectors is one of the reasons the authors decided to conduct the present study.

2.2. Best-Worst Method

In general, the procedure for MCDM methods involves two steps in which data are collected to estimate pairwise comparisons in the first step, and then the weights and ranking of criteria are calculated in the second step. Researchers can base procedures on information requirements, modeling efforts, or outcomes to choose a suitable MCDM method []. To evaluate and rank identified factors, models that might be considered include the Measuring Attractiveness by a Categorical-Based Evaluation Technique (MACBE), Multi-Attribute Utility Theory (MAUT), Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), Analytic Network Process (ANP), and Best-Worst Method (BWM).

In this paper, the authors decided to choose the BWM due to its advantages over other MCDM applications. First, the BWM model considers fewer comparisons than matrix-based methods such as AHP, ANP, or TOPSIS. For example, the BWM model conducts 2n − 3 comparisons, as opposed to (n(n − 1))/2 comparisons in the AHP model. Second, in the BWM model, there are only two vectors for Best to others and Other to worst comparisons. It probably saves time needed for collecting data, calculating, and analyzing []. Third, the results provided by the BWM are highly reliable as the redundant comparisons are eliminated. The integer values (i.e., 1–9) scale is used to make pairwise comparisons in BWM, whereas AHP uses a fractional values scale (i.e., 1/9-9). This leads to easy analytical evaluation and interpretation of human perception for applying BWM Fourth, if the Consistency Ratio (CR) is greater than 0.1, AHP requires revision of all the comparisons in the matrix. Instead, it is more data-efficient when the BWM needs to revise only two vectors. In 2015, Rezaei introduced the Best-Worst Method to solve MCDM problems []. In BWM, the best and worst criteria are determined initially by Decision-Makers (DMs). Afterward, the DMs use the numeric scale as Table 2 to covert linguistic terms (i.e., from 1 = “Equally important” to 9 = “Extremely Important”) and make pairwise comparisons between the best-worst criterion and others. These comparisons become foundations for a mathematical model presented in the next section.

Table 2.

The numeric scale value for pairwise comparison.

The BWM has been applied to a wide variety of sectors such as energy industries, manufacturing, and operation management. For example, Ahmad et al. (2017) used BWM to evaluate factors forcing a sustainable supply chain for oil and gas []; Gupta et al. (2016) applied the hybrid approach of BWM and VIKOR to select the best airline []; Kheybari et al. (2019) implemented the BWM for bioethanol plants []; Liao et al. (2019) evaluated the performance of hospitals by using a hesitant fuzzy BWM []. However, a limited number of studies have applied the BWM in public sectors such as evaluating strategies, especially in prioritizing interventions in the crisis of the COVID-19 outbreak.

3. Methodology

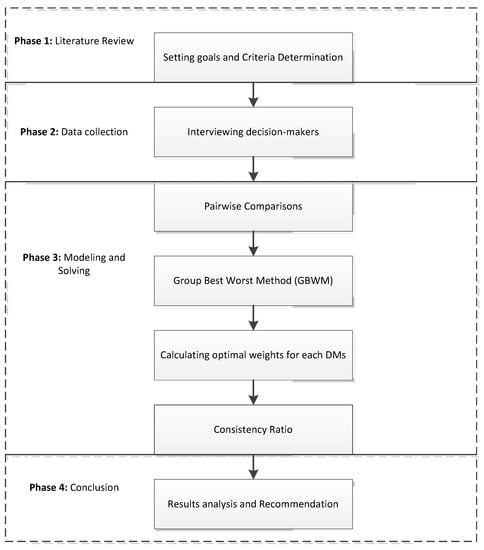

The study conducted a model of a two-stage approach combining the Best-Worst Method and Group Best-Worst Method (GBWM) to consider combining all DMs. In the first stage, the BWM is used to determine the local weight for each group of stakeholders, then in the second stage, the GBWM is applied to figure out the most efficient strategy prioritized by all DMs from five groups. In general, the procedure of BWM and GBWM models has the following basic steps (as in Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Research Framework.

Step 1: Setting goals and criteria determination

The relevant literature is reviewed and the decision criteria are identified.

Step 2: Data collection

The authors conduct interviews with experts or decision-makers (i.e., DMs) to collect data on the set of criteria. Afterward, the DMs use the numeric scale in Table 2 to covert linguistic terms (i.e., from 1 = “Equally important” to 9 = “Extremely Important”) and make pairwise comparisons between the best-worst criterion and others.

Step 3: Modeling and Estimation

The authors estimate the pairwise comparison of preferences between the best-worst criterion and all other criteria. The Best to Others (OB) and Others to Worst (Ow) preferences are shown in Equations (1) and (2) below.

OB = (OB1, OB2, OB3, …, OBn)

Ow = (O1W, O2W, O3W, …, OnW)

In which, OBj and OjW represents the pairwise preference value between best to other criteria j and j to worst criterion, ∀j = 1, 2, …, n.

To find the optimal weights (W1*,W2*, …, Wn*) for ranking of criteria, the following mathematical program model of GBWM is utilized as equations below.

Min ξ

Subject to

In which,

WB and WW: the weights of the most (best) and the least (worst) important criteria, respectively.

D: the set of Decision-maker; j index for criteria; λk: the weight of decision-maker k

Wj: the weight of criterion j

ξk: the inconsistency in pairwise comparisons obtained by kth decision-maker

Step 4: Consistency Ratio (CR)

A comparison is fully consistent if , where OBW is the preference of best criterion over worst criterion

The optimal values are used to calculate the consistency ratio for each decision-maker (CRk) and group decision making (CRG) as below

In which, is the optimal value of inconsistency for the kth decision-maker

λk: the weight given to the kth DM based on expertise level

CI: Consistency Index values are given in Table 3, corresponding to the value of OBW as CRG decreases, the consistency increases and if CRG = 0, it implies that the solution is fully consistent.

Table 3.

Consistency Index (CI).

4. Data Collection

The COVID-19 outbreak has caused many challenges and impacts on the countries that have encountered it. These consequences have been more serious in poor or developing countries which have limited resources. The pandemic has had major effects on Asia-Pacific nations, from territories’ economies to health systems. For instance, Vietnam has experienced a fourth COVID-19 outbreak. The practice of selecting the most optimal strategy is very challenging for decision-makers and attracts high public attention due to the involvement of various criteria and the interests of different stakeholders. In addition, the replication of the pandemic strategies of developed nations in developing countries faces many barriers due to the different capabilities of each country. The practice of prioritizing strategies is necessary for any government, especially in a developing country like Vietnam.

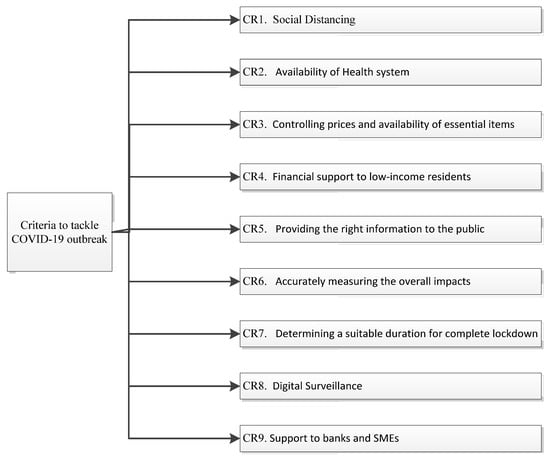

The study implemented the Delphi method to determine the set of criteria for evaluating the efficiency of the intervention. This means that the authors have reviewed relevant literature such as Thunstrom et al. (2020) for the criterion of social distancing []; Ranney et al. (2020) for the criterion of Health system []; or Kumar et al. (2020) for the criterion of Digital surveillance [], etc. The description of each criterion is referenced in Table 4. Afterward, the list of criteria is proposed to experts for review. After several rounds of discussion and revision, the list is finalized with nine criteria that decision-makers consider for tackling COVID-19 strategies, as shown in Figure 2.

Table 4.

Description of Criteria.

Figure 2.

Criteria for a tackling COVID-19 outbreak.

The authors used flexible online interviewing to collect data from five groups namely academicians, health workers, social workers, entrepreneurs, and common residents.

The “Academician” group includes people who are researchers, teaching assistants, and lecturers at two big national universities. The group of “Health Workers” includes doctors and nurses working at a local hospital. The group of “Social Workers” includes staff working at two social clubs and a non-profit organization. The “Entrepreneur” group includes managers and owners of five different companies. The group of common residents includes people living in Ho Chi Minh City who have experienced serious impacts during the COVID-19 outbreak.

In a study evaluating strategies to tackle COVID-19, Naeem et al. (2021) made a questionnaire to conduct a survey for four groups of decision-makers including health workers, academicians, social workers, and common citizens []. These groups of stakeholders are all impacted by the COVID-19 outbreak. However, in the present study, the authors consider one more group of entrepreneurs who have been negatively affected by the pandemic. From different backgrounds, these groups of evaluators are expected to give different viewpoints on the various interventions implemented by the government. Therefore, the authors decided to conduct this study with five groups of decision-makers including academicians, health workers, social workers, entrepreneurs, and common residents.

The data collection process includes two parts, in which the former is related to demographic information and the impact of COVID-19, and the latter process is making pairwise comparisons among different criteria. The representatives of groups are approached and invited to participate through online channels. An online survey is designed with some questions related to their demography as well as the impacts of COVID-19 on them. In the latter, respondents are asked to choose the most and least important and make the relative level between strategies by choosing the most and the least importance on a scale 1–9 as mentioned previously. Finally, the software BWM solver [] was used to calculate the weights of the criteria for each group of stakeholders.

5. Results

A total of 43 responses were collected, but we selected 40 responses (i.e., eight decision-makers for each group) because of incomplete answers. A total of five models as below with D1, D2, D3, D4, D5, respectively, represent five groups of eight decision-makers, namely Academicians, Entrepreneurs, Commons Residents, Social Workers, and Health Workers. The models use the common symbols defined as below

WB and WW: the weights of the most (best) and the least (worst) important criteria, respectively.

D: the set of Decision-maker; j index for criteria; λk: the weight of decision-maker k

Wj: the weight of criterion j

ξk: the inconsistency in pairwise comparisons obtained by kth decision-maker.

5.1. Model for Academicians

Subject to

The pairwise comparison by Academicians are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

The pairwise comparison by Academicians.

5.2. Model for Entrepreneurs

Subject to

The pairwise comparison by Entrepreneurs are presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

The pairwise comparison by Entrepreneurs.

5.3. Model Used to Common Residents

Subject to

The pairwise comparison by Common Residents are presented in Table 7.

Table 7.

The pairwise comparison by Common Residents.

5.4. Model for Social Workers

Subject to

The pairwise comparison by Social Workers are presented in Table 8.

Table 8.

The pairwise comparison by Social Workers.

5.5. Model for Health Workers

Subject to

The pairwise comparison by Health Workers are presented in Table 9.

Table 9.

The pairwise comparison by Health Workers.

5.6. Local Weights of Criteria

The results are obtained and ranked in Table 10. These values are local weights implying the important level of each criterion evaluated by each group.

Table 10.

Ranking of strategies with respect to the group of stakeholders.

The values of , CRk for each DM is obtained to determine the CRG for each group as Table 11. The values of CRk for each DM and CRG for groups are consistent and acceptable. The least value of consistency is for Academicians with CRG = 0.0567, and the most consistent value is for the Social Workers group with CRG = 0.0194.

Table 11.

Group Consistency ratio (CRG).

5.7. Global Weights of Criteria

The weights presented in Table 10 are local weights with respect to pairwise comparisons of each group. To suggest an effective strategy, however, the global weights of all criteria need to be estimated. The authors consider the preference of all groups together with a new mathematical model based on GBWM as follows []:

Subject to

In which, , , , , are the corresponding weights assigned, respectively, to the group of Academicians, Entrepreneurs, Commons Residents, Social Workers, and Health Workers. The sum of all weights equals 1, i.e., + . To have a more precise analysis, the authors decided to set up four different scenarios with different weights for each group as Table 12. In the Weight Set 1 (WS1), the authors set all weights equally for all groups. However, the weights are varied for each group because of different expertise levels and knowledge about the COVID-19 outbreak. In these weight sets, the Health Workers group is given the highest weightage .4–0.5) and the Social Workers group is given the second-highest weightage –0.3) due to their expertise concerning the pandemic.

Table 12.

Weight set (WS) values of , , , , , respectively.

Table 13 presents the global weights of strategies obtained when we combine all preferences of all groups together. Across different scenarios with the weight sets varied, the second criteria (i.e., Availability of Health Systems) is evaluated as the most important strategy by all decision-makers. Then, the “Social Distancing” (CR1) and the “Providing the right information to the public” (CR5) are second-most important. The three least important strategies are namely determining a suitable duration for complete lockdown (CR7.), Digital Surveillance (CR8.), and support to banks and SMEs (CR9.).

Table 13.

Global weights and ranking of criteria for each weight set.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

The practice of determining the most prioritized strategies to tackle the COVID-19 outbreak is attracting a great deal of concern among government officials. This is a complex decision with multiple challenges and criteria that directly or indirectly influence the interests of stakeholders. One of the efficiency techniques is the Multiple-Criteria Decision Making model and the Best-Worst Method is chosen to apply for this case due to its advantages in data collection and calculations. The study shows differences in selecting the prioritized actions between developed countries and developing or poor countries. Decision-making has become more challenging for governments of developing nations and Vietnam is an example, especially when the Delta Variant of coronavirus is fast-spreading and threatening all aspects of Vietnam.

In the proposed research model, the authors considered a total of nine strategies applied in many countries around the world. These strategies are entitled Social Distancing (CR1.); Availability of Health Systems (CR2.); Controlling prices and ensuring availability of essential items (CR3.); Financial Support to low-income residents (CR4.); Providing the right information to the public (CR5.); Accurately measuring the overall impacts (CR6.); Determining a suitable duration for complete lockdown (CR7.); Digital surveillance (CR8.); Support to banks and SMEs (CR9.). These strategies are set as nine criteria in the BWM model. The authors have conducted online interviews with five different groups of stakeholders (i.e., Academicians; Entrepreneurs; Common Residents; Social Workers, and Health Workers) to evaluate and rank the most important levels of all criteria. Then, the extended BWM model known as the GBWM model is applied to identify the global weightage and suggest the most efficient strategy.

The results of local weights have shown the most and least important criteria for each group of stakeholders. For the group of Academicians and Health Workers, the Availability of Health Systems (CR2.) is evaluated as the most important criterion; health workers have a better understanding of the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the pressure of the health system than anyone. It is important to ensure the quantity of equipment for treatment and protection during pandemic outbreaks. The group of Entrepreneurs and Social Workers, meanwhile, evaluated Providing the right information to the public (CR5.) as the most important criteria because fake news is also a barrier to their plans and makes people feel puzzled. The criterion Controlling prices and ensuring availability of essential items (CR3.), however, can be seen as the most important to the Common Residents’ group. This may be explained by its direct impact on the daily life of residents. If the prices of necessary categories are not controlled, it may cause trouble in the market with supply and demand. Poor people would be significantly influenced. On the other hand, the group of Academicians and Entrepreneurs evaluated Determining a suitable duration for complete lockdown (CR7.) as the least important strategy. A complete lockdown seriously impacts economic activities, and for this reason, Entrepreneurs do not favor this intervention. The Support to banks and SMEs (CR9.) strategy is the lowest priority for the group of Social Workers and Health Workers. For these groups, the health of people and the stability of society are the most important priorities. The group of Common Residents ranked Digital Surveillance (CR8.) as the least important strategy due to its privacy issues.

In the next stage, the authors implemented the GBWM to determine the most efficient and prioritized strategy by combining all decision-makers together. Taking the advantage of considering fewer pairwise comparisons and providing more reliable outcomes from the GBWM model, the global weights of criteria are estimated and ranked across different weightage sets. The results of global weights have shown that the availability of Health Systems (CR2.) is the most prioritized criterion for all decision-makers. This finding is also consistent with the local weight results mentioned above and many previous studies by Nardo et al. (2020) []; Naeem (2021) [] and so on. This is also aligned with the director-general of the World Health Organization’s (WHO) argument in the journal Nature: “the provision of universal health care remains a priority… Governments, scientists, and the public should support this goal because it’s in everyone’s best interests.” []. In addition, the practical utility of results could be useful for governments, particularly in developing nations like Vietnam. Due to the limited resources in such nations, it is important to have optimization strategies in healthcare settings. Such practices increase the availability of Health Systems, the criterion that was shown as the most prioritized intervention in the findings of the present study.

The limitation of this study is its sample of only 40 decision-makers from five different groups that are not representative of the whole of the country. In addition, the categories of decision-maker groups should be more varied such as government representatives; public health scientists, who play key roles in issuing the interventions. This leads to challenges in determining the generalizability of the findings. However, the present study contributes not only to the literature on decision-making with complex combined interests of different stakeholders, but the results also provide useful references to support decision-makers such as policymakers in prioritizing the strategies for tackling COVID-19 outbreaks. This research framework could be duplicated in any context or any country because the respondents do a simple task by giving comparisons through a numerical scale. Moreover, the proposed model is a good example of BWM and GBWM applications in dealing with a complex problem and minimizing the conflicting interests of different stakeholders. For future studies, this work can be extended by combining other MCDM methods such as AHP, DEA, TOPSIS, and others to provide additional insight into decision-making problems not only in health public sectors but in various fields.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.-P.N. and C.-N.W.; methodology, H.-P.N.; software, Y.-H.W.; validation, H.-P.N. and C.-C.H.; formal Y.-H.W.; analysis, investigation, H.-P.N.; resources, C.-N.W.; data curation, C.-C.H. and H.-P.N.; writing—original draft preparation, H.-P.N.; writing—review and editing H.-P.N.; visualization, H.-P.N. and Y.-H.W.; supervision, C.-N.W.; project administration, C.-N.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- WHO. Director-General’s Remarks at the Media Briefing on 2019-Ncov on 11 February 2020; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Worldometers.Info. Available online: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/ (accessed on 18 June 2021).

- Naeem, A.; Md, G.; Hasan, R.; Karim, B. Identification and prioritization of strategies to tackle COVID-19outbreak: A group-BWM based MCDM approach. Appl. Soft Comput. 2021, 111, 107642. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.N.; Nguyen, H.P.; Wang, J.W. A Two-Stage Approach of DEA and AHP in Selecting Optimal Wind Power Plants. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2021, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.; Nguyen, T. Using optimization algorithms of DEA and Grey system theory in strategic partner selection: An empirical study in Vietnam steel industry. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2020, 7, 1832810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia-Nan, W.; Hoang-Phu, N.; Cheng-Wen, C. Environmental Efficiency Evaluation in the Top Asian Economies: An Application of DEA. Mathematics 2021, 9, 889. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.-N.; Nguyen, H.-P. Evaluating the sustainability of hotels using multi-criteria decision making methods. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng.-Eng. Sustain. 2022, 164, 19–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, J. Best-worst multi-criteria decision-making method. Omega 2015, 53, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araz, O. Integrating complex system dynamics of pandemic influenza with a multi-criteria decision making model for evaluating public health strategies. J. Syst. Sci. Syst. Eng. 2013, 22, 319–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, D.; Gunasekaran, M. Assessment of vaccination strategies using fuzzy multi-criteria decision making. In Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Fuzzy and Neuro Computing (FANCCO-2015), Hyderabad, India, 17–19 December 2015. [Google Scholar]

- von Neumann, J.; Morgenstern, O. Theory of Games and Economic Behavior, 2nd ed.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1947; p. 641. [Google Scholar]

- Charnes, A.; Cooper, W.W.; Rhodes, E. Measuring the efficiency of decision making units. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1978, 2, 429–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L. The Analytical Hierarchy Process; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, C.L.; Yoon, K. Multiple Attribute Decision Making: A State of the Art Survey. In Economics and Mathematical Systems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1981; p. 186. [Google Scholar]

- Guitouni, A.; Martel, J.; Vincke, P.; North, P. A framework to choose a discrete multicriterion aggregation procedure. In Defence Research Establishment Valcatier (DREV); Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- José, L.d.S.G.; Valério, A.P.S. ANP applied to the evaluation of performance indicators of reverse logistics in footwear industry. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2015, 55, 139–148. [Google Scholar]

- Pooripussarakul, S.; Riewpaiboon, A.; Bishai, D.; Muangchana, C.; Tantivess, S. What criteria do decision makers in thailand use to set priorities for vaccine introduction? BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Samanlioglu, F. Evaluation of influenza intervention strategies in turkey with fuzzy ahp-vikor. J. Healthc. Eng. 2019, 2019, 9486070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Majumder, P.; Biswas, P.; Majumder, S. Application of new topsis approach to identify the most significant risk factor and continuous monitoring of death of COVID-19. Electron. J. Gen. Med. 2020, 17, em234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ahmad, W.; Rezaei, J.; Sadaghiani, S.; Tavasszy, L. Evaluation of the external forces affecting the sustainability of oil and gas supply chain using best worst method. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 153, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, H.; Barua, M. Identifying enablers of technological innovation for indian msmes using best–worst multi criteria decision making method. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2016, 107, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kheybari, S.; Kazemi, M.; Rezaei, J. Bioethanol facility location selection using best-worst method. Appl. Energy 2019, 242, 612–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.; Mi, X.; Yu, Q.; Luo, L. Hospital performance evaluation by a hesitant fuzzy linguistic best worst method with inconsistency repairing. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 232, 657–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thunstr¨om, L.; Newbold, S.; Finnoff, D.; Ashworth, M.; Shogren, J. The benefits and costs of using social distancing to flatten the curve for COVID-19. J. Benefit-Cost Anal. 2022, 11, 179–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranney, M.; Griffeth, V.; Jha, A. Critical supply shortages—the need for ventilators and personal protective equipment during the COVID-19 pandemic. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, e41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Sharma, K.; Singh, H.; Naugriya, S.; Gill, S.; Buyya, R. A drone-based networked system and methods for combating coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2020, 115, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Kumar, R.; Panchal, R.; Tiwari, M. Impact of COVID-19 on logistics systems and disruptions in food supply chain. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020, 59, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buheji, M.d.; Cunha, C.K.; Beka, M.G.; de Souza, B.; Costa, S.; Hanafi, S.; Yein, T. The extent of COVID-19 pandemic socio-economic impact on global poverty. A global integrative multidisciplinary review. Am. J. Econ. 2020, 10, 213–224. [Google Scholar]

- Ros, M.; Neuwirth, L. Increasing global awareness of timely COVID-19 healthcare guidelines through fpv training tutorials: Portable public health crises teaching method. Nurse Educ. Today 2020, 91, 104479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loomba, S.; de Figueiredo, A.; Piatek, S.; de Graaf, K.; Larson, H. Measuring the impact of COVID-19 vaccine misinformation on vaccination intent in the uk and usa. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2021, 5, 960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nilima, N.; Kaushik, S.; Tiwary, B.; Pandey, P. Psycho-social factors associated with the nationwide lockdown in india during COVID-19 pandemic. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2020, 9, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utz, R.; Feyen, E.; Ahued, F.V.; Nie, O.; Moon, J. Macro-Financial Implications of the COVID-19 Pandemic; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Nardo, P.D.; Gentilotti, E.; Mazzaferri, F.; Cremonini, E.; Hansen, P.; Goossens, H.; Tacconelli, E. Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis to prioritize hospital admission of patients affected by COVID-19 in low-resource settings with hospital-bed shortage. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 98, 494–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nature. Universal Health Care Must Be a Priority—Even Amid COVID; Nature: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).