1. Introduction

Given the current COVID-19 pandemic, the local food systems need to be overhauled to strengthen their capabilities, primarily where smallholders operate. The strengths and weaknesses of farmers’ knowledge systems are dynamic and valuable, especially in delivering transformative knowledge to improve farmers’ food security and livelihoods [

1,

2]. Knowledge in agriculture is a stimulating factor that increases farmers’ productivity through the better utilisation of resources [

3]. Thus, evaluating the role of human capital in agricultural growth is essential, as it corresponds with other capitals involved in the improvement of food production. This study argues that farmers’ knowledge and empowerment can be achieved by integrating the institutional channels and active social systems in their environment. Nevertheless, the opinion leaders within the communities also significantly influence their fellow farmers [

4,

5]. These opinion leaders vary in their extent of impact; they hold different professional and social positions and frame different communication channels with their active farmers in knowledge systems [

6,

7].

Evolving social knowledge systems consist of key actors connecting farmers within and outside their local knowledge systems [

5,

8]. In farming communities, knowledge is a social construct informed by overlapping paradigms that are continually evolving [

1], where farmers learn through communications with others and direct observations [

1,

9,

10]. Within these knowledge paradigms around farmers, opinion leaders exist. These key individuals are held in high esteem by farmers who accept and follow their opinions [

5,

11]. Ref. [

12] highlights these farmers’ behaviour and argues that smallholder farmers do not simply adjust to expert recommendation. Instead, their fellow farmers are highly influenced by behaviour and attitudes, thus shaping their decision-making. Therefore, actors’ critical role is fundamental to understanding knowledge sharing within their social knowledge systems and settings. The objective of this study is to explore the types and characteristics of opinion leaders from farmers’ perspective, and the socio-economic characteristics of farmers and the dynamics of opinion leaders to build resilient farming as these social knowledge paradigms of systems grow among farmers and communities of South Africa. Thus, paving the way to transformative knowledge systems that increase the inclusion and participation of relevant actors in building transformative systems in facing the COVID-19 pandemic, market access and inflations of produce and inputs.

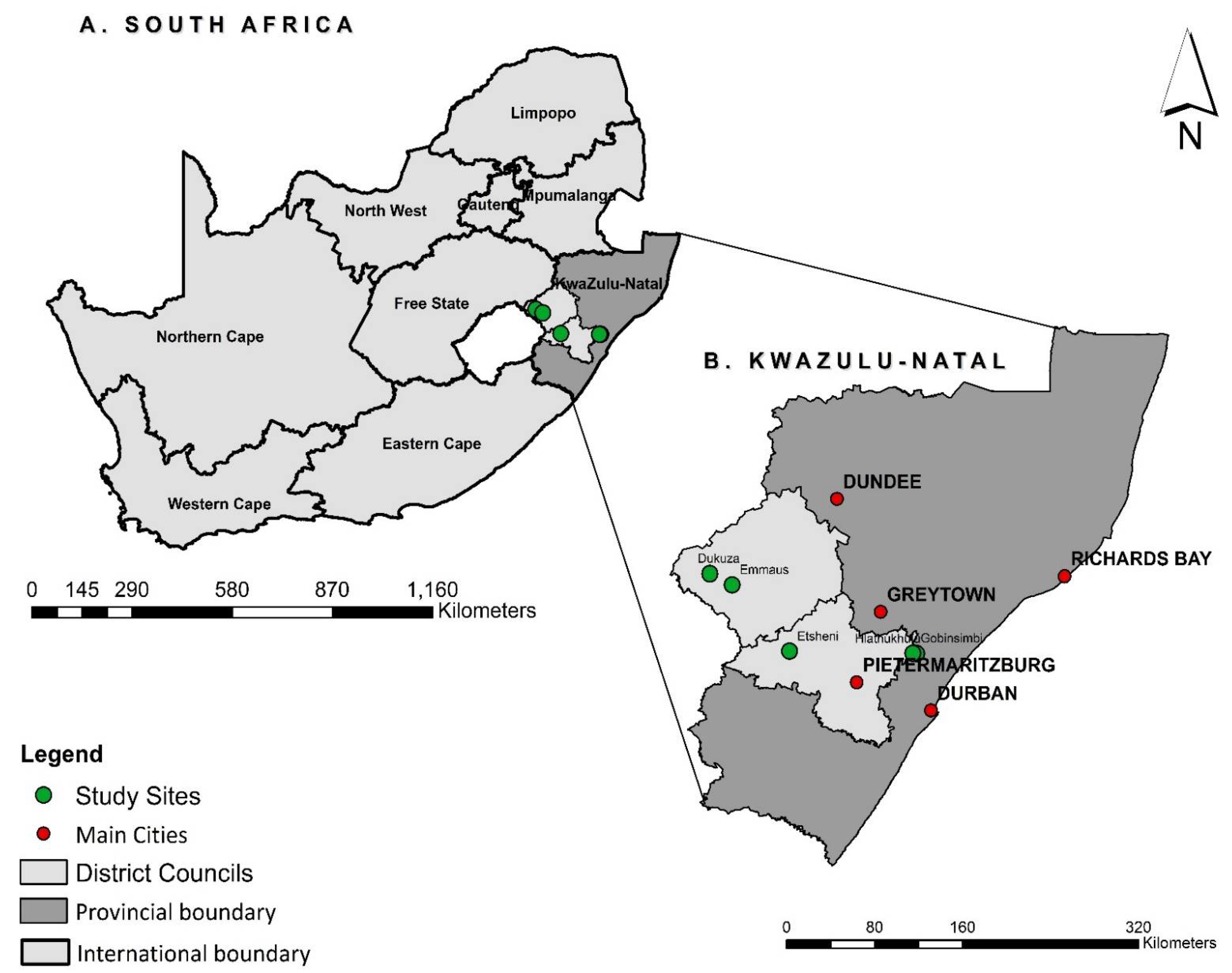

In the province of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, active smallholder farmers have self-organised, forming networks with formal and informal actors within agricultural systems [

2]. These farming knowledge systems contain experts who are professional farmers and provide agricultural advice to other farmers. Thus, such relationships and networking shapes farmers’ knowledge and further shows the shifting roles of farmers as teachers, learners, and networkers, according to [

1]. This study argues that identifying the types of these opinion leaders is essential for understanding their work and extent in strengthening the human capacity, and for the professional development of these opinion leaders, who are regularly connected with farmers, especially in this COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, it considers that these key farmers are influential navigators in complex communities, where they successfully exert an influence from within the organisational dynamic. The study hypothesis is that opinion leaders’ presence could explain why some farmers progress further than their peers. To tap into and utilise opinion leaders, it is crucial to know their profile characteristics and the extent of their influence on farmers. To understand beyond the knowledge system, there is a need to place special attention on the key opinion leaders in the system to the farmers. Several studies, including those of [

13] as well as [

14], are in agreement regarding the importance of opinion leaders in the agricultural sector for the flow of knowledge and information to improve farmers’ skills as a pathway towards poverty reduction.

The authors of [

15,

16,

17] emphasis that communities have complex networks of social relationships with various socio-economic groups and experience different power relations across farming systems. All these aspects might shape farmers’ decisions regarding opinion leaders. Therefore, understanding the impact of socio-economic factors is needed in determining farmers’ choice of opinion leaders. Some farmers have more experience in agriculture and leadership qualities within farming communities, consisting of social systems, than others [

17]. Moreover, the number of experienced farmers in a rural area determines the depth and strength of the relationship between these farmers and other farmers’ knowledge and decision-making. Furthermore, [

15,

16] supported this argument, highlighting that some farmers may be leaders in multiple fields, while others may have leadership roles limited to specific issues and activities. Before making decisions, a farmer often seeks advice from their opinion leaders to validate their knowledge. Therefore, the study questions the characteristics and socio-economic factors that influence and determine opinion leaders from farmers’ perspective.

Leaders can convey knowledge convincingly to their peers through their influence, primarily if they use the same language [

18]. The authors of [

7,

8,

19] describe these key actors as the farmers’ mouthpiece before the extension agency and advisor, and they elaborate on the needs of local farmers. Numerous studies have attempted to identify the characteristics of opinion leaders [

5,

14,

20]. Although the importance of opinion leaders has been acknowledged, there have not been many attempts to measure and explore the extent of their influence on their fellow farmers. This study aimed to fill this gap and explore which measures farmers use to choose their opinion leaders. In other words, to utilise existing opinion leaders effectively, it was necessary to clearly understand the nature of opinion leadership among the farmers in rural settings. This research aimed to be helpful in the assessment of the role played by opinion leaders in agricultural development. Furthermore, the study aimed to add knowledge to the existing literature on opinion leadership and the extent of the influence of opinion leaders in the agricultural sector by asking the following questions.

Whom do you go to for information or advice when you have a farming question within your area? How often do you interact with the mentioned person about agricultural problems and activities? Which channels of communications do you use to interact and share knowledge with this fellow farmer?

Which characteristics do you use to choose the mentioned opinion leaders? What makes you consider this fellow farmer?

2. Literature Review

According to Katz and Lazarsfeld (1955), opinion leaders are individuals who receive information from the media and pass it along to their peers in the environment [

8]. This theory suggests that opinion leaders aggressively seek information and knowledge as well as frequently discussing issues they encounter [

8]. These opinion leaders are found in every social group, regardless of level, in various age groups and in all professions. However, [

8] maintain that effective opinion leaders tend to be slightly higher than their followers are in terms of status, asset ownership, income, and educational level. According to [

21], Chau and Hui (1998) identify three ways in which opinion leaders exert influence on the decisions of others [

8]. Opinion leaders act as role models who inspire imitation; they spread information via word of mouth; and they give advice [

1,

22]. These ways in which opinion leaders exert influence have also been observed among smallholder farmers in the province of KwaZulu-Natal. Farmers in their communities are vehicles of power and their behaviour and social relations are deeply linked to power. Farmers follow and trust the opinion of those whom they perceive to be successful in their farming and tend to associate with them to learn more about farming [

5,

23].

An effective and efficient information delivery system thus performs a critical role in providing reliable and useful information to farmers. Rural communities have visible and invisible interrelated interaction routes between the farmers and the network of social communication that must be explored. Some networks serve as linking structures for accessing and sharing knowledge by agricultural sectors and farmers [

7,

8,

24]. Each of these channels has an impact on smallholder farmers’ sharing and acquiring knowledge in rural communities [

9,

24,

25]. These include transition agents, field workers and officers for extensions, facilitators, and teachers. Such people have a strong responsibility to act as channels for communication [

26]. Local authorities, agricultural unions and associations of farmers can also be channels for interconnection.

The author of [

22] found that leadership empowerment has a significant impact on members’ knowledge-sharing behaviour in a system. Local leaders who interact with farmers daily have an impact on their behaviours and perceptions and influence a community’s overall capacity [

17,

27]. This study posits that the effective manner to progress towards sustainable agriculture in rural communities is through institutional and social leaders, and their influence over their followers must therefore be established and understood. These influential people affect others through persuasion, by providing information and by serving as an example for people in their community [

28,

29].

Farmers have motives and values that are influenced by logical, ethical, emotional, and social factors, which direct them in choosing which information to obtain, the sources they pursue, and the learning methods they follow [

18,

30]. If a farmer has no such experience, gaining and integrating new information properly will be difficult and empowerment could remain beyond their reach.

4. Results

According to

Table 2 below, 54.8% of the farmers mentioned agricultural advisers as their opinion leaders according to smallholder farmers’ classification of opinion leaders. These agricultural advisors formally represented the local Department of Agriculture and Rural Development (DARD), working with smallholder farmers. These advisors had formal qualifications, i.e., a degree or diploma in agriculture (education or farming training). This highlights a strong relationship between farmers and extension advisors. These results are concurrent with the findings of studies conducted by [

6,

9,

15] that show that farmers also use the expertise from formal agricultural institutions to provide training courses, agricultural exhibitions, field days, and demonstrations in many instances. Secondly, 29.2% of the farmers mentioned fellow farmers (the farmers’ group members) as their opinion leaders. Furthermore, the farmers mentioned that these opinion leaders held administrative positions within their farmers’ group due to their years of farming experience. Moreover, they mentioned that these opinion leaders were located within the community.

The study results described in this article revealed that 16% of the farmers indicated group leaders as their only opinion leaders. Moreover, they availed themselves of the information to which these leaders had access. Group members selected these leaders to represent their farmers’ group, and they were chosen based on their farming experience. The opinion leaders held status positions, making it easy to infiltrate and influence others around them. They were located within the community, and thus, their followers (farmers) could observe their agricultural actions and outcomes. Furthermore, they could remind others of the technical specifications they used during meetings and field demonstrations.

4.1. The Extent of Opinion Leadership

The results revealed that the farmers’ nomination of an individual reflected the individual’s influence on them. This was shown by the number of farmers who nominated extension advisors as their opinion leaders, which revealed the extent of their influence and leadership. The probable reason could be that the extension advisors had more access to resources and other knowledge systems. Moreover, they were more socially active with the farmers.

4.2. Characteristics of the Opinion Leaders Selected by Smallholder Farmers

The characteristics of opinion leaders collected from the farmers included the channel of communication, the frequency of meetings, the consultation structure, and the system of the farmers with their opinion leaders. The findings relating to these characteristics are discussed and presented in

Table 3 below.

4.3. Channels of Communication Used by Farmers with Their Opinion Leaders

The respondents were asked to indicate the channels of communication used by their opinion leaders. Most farmers mentioned attendance and participating in farmers’ group meetings as their most important communication channels with their mentioned opinion leaders. In this way, they learned from their opinion leaders while sharing their individual experiences and addressing common problems. Another group of farmers revealed that they participated in field demonstrations with agricultural advisors for learning and observing technically transferred skills. Another group of farmers used cell phones to communicate with agricultural advisors, arrange meetings, and follow up on various matters regarding agriculture. These farmers participated in field visits and attended farmers’ group meetings to communicate with agricultural advisors and group leaders. This is further supported by [

37], who argued that farmers are experimental people who believe in physical observations and outcomes. This triggers collective and social learning, and the acquiring of resources to improve their knowledge and agricultural production. During the focus group discussion, farmers explained that they used cell phones to arrange meetings with extension officers and fellow farmers. After attending the meetings, field learning and demonstrations were conducted to deal with the practical aspects of the agricultural topics discussed. Field visits were conventional communication channels frequently used by farmers and were considered practical as they made the information easier to understand.

4.4. Placing Farmers’ Interaction with Opinion Leaders

The farmers were asked to indicate the frequency of their interaction with their opinion leaders. The findings shown in

Table 3 indicate that the majority of the farmers met monthly with agricultural advisors. This was in line with the constitution of the farmers’ group organisation that advocates a compulsory monthly meeting of group members. These findings confirmed the role played by opinion leaders in the farmers’ knowledge flow. In addition, the findings showed that frequent interaction could be a crucial element of knowledge and learning for farmers. The statistical analysis revealed a statistical significance in the frequent meetings and interactions with the farmers’ opinion leaders. This showed that the farmers required a consistent flow of resources and knowledge. The time and energy spent by farmers building social relationships with these opinion leaders reflected the accumulation of information and resources gathered.

4.5. Consultation Structure and System of Farmers with Their Opinion Leaders

Regarding the extent of the consultation structure and system of the farmers with their opinion leaders, the survey showed that 54.8% of the respondents consulted in groups with extension advisors. However, 29.2% of the farmers held individual consultations with other group members and farmers’ group leaders. About 16% of the farmers held individual consultations with farmers’ group leaders. This shows that most farmers preferred group consultation with their opinion leaders to acquire knowledge and learning. The group consultations provided a space to meet other farmers and to re-engage with farmers. These group consultations serve as a space where farmers actively engage in social learning with their fellow farmers and extension advisors, which strengthens their trust. The statistical analysis revealed that the consultation structure used by farmers to meet with their opinion leaders was statistically significant.

4.6. Factors That Shape and Influence Farmers Choice of Opinion Leaders

This section summarises the answers to the open-ended questions about the farmers’ reasons for choosing opinion leaders. Issues related to accessibility, availability, and quick feedback regarding problems from leaders emerged as seeming to influence the farmers’ choice of opinion leaders. In

Table 4, out of 54.8%, 20.1% of the farmers who identified extension advisors as their opinion leaders maintained that their selection was based on the language (isiZulu) used in their interactions and on the proximity of the physical location of the meetings. Out of 16%, 4.1% of the farmers selected farmers’ group leaders (FGL) because they were physically located in the community. Moreover, 7.3% of 29.2% of the farmers selected farmers’ group members (FGM) because feedback was easily assessed and there was easy access to the farmers, as they were in the same community. This shows that the farmers required leaders who could quickly provide reliable and relevant information about their agricultural problems, thus building trust and relationships, leading to further interactions.

Furthermore, the results also revealed that language used to interact with opinion leaders is another crucial factor among farmers. This may be a result of a pattern of elderly and illiterate farmers engaged in agriculture. Thus, the language used to transfer the knowledge is essential for farmers to understand and utilise it. Therefore, the language and accessibility to sources of knowledge and feedback were crucial to the smallholder farmers included in the study.

4.7. Farmers’ Socio-Economic Factors That Influence Farmers’ Choice of Opinion Leaders

Before running the MNL model, the explanatory variables were checked for multicollinearity using the variation inflation factor (VIF) and contingency coefficient in the

Table A1 Appendix A. The variables had a high level of tolerance, which indicated that there was no severe multicollinearity among the variables used in the analysis. The demographic characteristics of farmers were subjected to the multinomial logistic (MNL) regression model. The results in

Table 5 indicate that all estimated coefficients are statistically significant, as reflected by the significant chi-square value (

p < 0.05). The pseudo R2 value is about 44.77%.

The model outcome shows that the education level of farmers significantly (

p < 0.05) positively influenced the choice of the respondents in choosing the farmers’ group leader, and farmers’ marital status negatively influenced the choice of the respondents in choosing farmers’ group leader (

p < 0.1). The interpretation of the odds ratio in favour of the probability of the respondents in choosing farmers’ group leader increases by 12.2% and decreases by 6.7%, respectively. This is supported by the argument of [

14], that absorption of knowledge by farmers to make choices is shaped by socio-economic aspects, such as education and age.

Engaging in agriculture for household consumption purposes significantly and negatively (p < 0.05) influenced the decision of farmers’ opinion leaders choosing the farmers’ group leader and farmers’ group members. The interpretation of the odds ratio depicted that if other factors are held constant, the odds ratio favours the probability of the farmers’ opinion in choosing the farmers’ group leader and farmers’ group members, decreases by the odds ratio of 12.3%, and 26.7%, respectively. This makes sense, because these farmers engage in agriculture for their household consumption instead of market sales; thus, their farming knowledge and network are efficient as they are not competing for market standards.

The agricultural skill held by opinion leaders has a significant and positive influence (

p < 0.05) on farmers’ choice in selecting the farmers’ group leader and farmers’ group member. The odds ratio interpretation depicted that, if other factors are held constant, the odds ratio in favour of the likelihood of the farmers to choose farmers’ group leader and farmers’ group member increases by 36.4% and 81.9%, respectively. This result agrees with the findings of a study conducted by [

9], which argues that smallholder farmers do not simply adapt to expert advice. Instead, their fellow farmers are highly influenced by behaviour and attitudes, thus shaping their decision-making.

5. Discussion

The study revealed that, although there was many extension agents and advisors who assisted them, the farmers still valued their peer farmers as opinion leaders in farming. These results are supported by [

20], whose study highlighted that local farmer are sufficiently good sources of information and advice for the community. These opinion leaders shared new information and their experience with other farmers in their social network systems, as they were progressive opinion farmers. Some opinion leaders were significant in the extent of their offering opinion leadership, which showed that they were precious to their network system. Thus, they could be exploited by system agents in the formation of knowledge. The mentioned opinion leaders had monthly interactions with the farmers, and the farmers consulted with these opinion leaders mostly through group settings, which allows them to learn from one another, especially regarding issues already experienced by their peers. These findings agree with the explanation and characteristics of opinion leaders given by [

1,

22], who highlight opinion leaders as role models who inspire imitation, spread information via word of mouth, and give advice to their followers. These facts explain why numerous farmers choose to seek information and advice from their mentioned opinion leaders. However, some farmers consulted fellow group members and farmers group leaders individually.

These farmers participated in field demonstrations and visits and attended farmers’ group meetings to communicate with agricultural advisors, group leaders and group members. Field demonstrations events were highly used and preferred by these smallholder farmers and were identified as a good platform for social interaction opportunities, to establishing new relationship for agricultural related activities. These finding aligned with the study of [

15,

36], who argue that smallholder farmers also utilise the expertise of formal agricultural institutions, which provide training courses, agricultural exhibitions, field days and demonstrations, and thus, further encourage new relationships. Moreover, this platform is conducive to peer-to-peer learning, where farmers can physically engage and see activities. Such platforms can immediately enforce the take-up of innovations by smallholder farmers.

The social status of opinion leaders within local hierarchies played an essential role in their selection as possible leaders. According to the study of [

18,

30], farmers have motives and values that are influenced by logical, ethical, emotional, and social factors, that direct them in choosing which information to obtain, the sources they pursue and the learning methods they follow. Moreover, as the study results disclosed, the proximity of the opinion leaders to other farmers meant physical accessibility concerning the knowledge source, which was crucial for the smallholder farmers.

Educational level of farmers had an influence on the type of opinion leader selected by the farmers. This is supported by [

12], who argue that absorption of knowledge by farmers to make choices is shaped by socio-economic aspects, such as education and age. Moreover, these types of existing opinion leaders within farmers’ social knowledge systems illustrate the argument of [

1]; that within farming activities and knowledge transformation, there are shifting roles of farmers as teachers, learners, and networkers. The agricultural skill held by opinion leaders had a significant and positive influence on farmers’ choice of opinion leader. Thus, the agricultural experience of farmers in a rural area influences the depth and strength of the relationship between the farmers and other farmers’ knowledge, and, thus, influences farmers decision-making.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

It can be concluded that opinion leaders played a significant role in updating farmers and helping farmers with their problems. Farmers received and trusted advice from farmers within their communities. These farmers engage with familiar people from their environment and surroundings. They require more physical engagement to influence change and transformative learning. Knowledge is not extended but communicated directly through learning and action, which thus critically encourages participation of farmers, leading to farmer-facilitated knowledge. The study showed that the accessibility of the knowledge source and feedback were crucial to farmers. Thus, we can conclude that the accessibility of the opinion leaders was considered when choosing the knowledge adviser on the part of the farmers. These opinion leaders require continuous assessment to enhance and integrate their leadership skills and promote empowerment programmes for farmers. These facts explained why many of the farmers chose to seek information and advice from their opinion leaders.

The agricultural extension and agricultural production enhancement programmes must recognise the active opinion leaders within communities to develop and strengthen the efforts and impact of these programmes for more resilient outcomes. The progressive and effective interactions of these opinion leaders need a constant, continuous assessment to increase and integrate leadership skills on empowerment programmes of farmers. In light of the findings, it is suggested that efforts to improve farmers’ active knowledge systems and access to the opinion leaders within these active knowledge systems should take into consideration the socio-economic factors that influence farmers’ choices and participation in social systems and social interactions. This will thus pave a way to transformative knowledge systems and increase the inclusion and participation of relevant actors in building transformative systems. These research findings may help agents develop their understanding of the dynamics of local communities and the social complexity that shapes farmers’ environments and decisions. The KwaZulu-Natal Department of Agriculture and Rural Development (DARD) and various non-government agencies need to have access to updated information for transformative initiatives and platforms that intend to transform and empower farmers through local and private networks. Further research can be conducted on how opinion leaders can be integrated and institutionalised at both the local and district levels and integrate psychological dimensions into every development initiative and programme offered to farmers.