1. Introduction

On the one hand, scientists and society alike typically think of intelligence as an ability or a set of abilities (e.g.,

Carroll 1993;

Deary 2020;

Kaufman et al. 2020;

McGrew 2009;

Spearman 1904;

Sternberg 2020). On the other hand, both scientists and laypeople know that people who have high intelligence often act in surprisingly “stupid” or foolish ways (

Aczel 2020;

Sternberg 2002). In some cases, they may lack emotional intelligence (

Rivers et al. 2020), social intelligence (

Kihlstrom and Cantor 2020), cultural intelligence (

Ang et al. 2020), or what Gardner calls interpersonal intelligence (

Gardner 2011); but in other cases, the problem may seem to be not a lack of ability but rather the attitude with which they approach a task requiring intelligence: they seem to self-sabotage their performance by going into the task with an attitude that will lead to failure or defeat;

Sternberg (

2022) has referred to this phenomenon as a failure of intelligent attitude. Relevant also is the construct of self-handicapping, whereby people purposely set up obstacles in their way, sometimes to blame failure in tasks on external causes rather than on themselves (e.g.,

Berglas and Jones 1978;

Jones and Berglas 1978).

At one point in the history of social psychology, investigators recognized how seeking cognitive consistency was a major motivating source in people’s lives (e.g.,

Abelson et al. 1968;

Brehm and Cohen 1962;

Cialdini et al. 1981). People could deal with cognitive inconsistencies in more or less adaptive (what are here called “adaptively intelligent”) ways. For example, if someone finds out negative information about a person in power or a person seeking power, or a loved one, for that matter, they can, in

Piaget’s (

1952) terminology, assimilate the information and accept it, or accommodate that negative knowledge, creating a new cognitive structure; or if accommodation fails, they can simply deny the validity of the information or even that the information exists.

In this article, an ability is defined as a developed cognitive or related capacity that can be modified, at least to some degree, through instruction and effort (

Sternberg 2022). This definition is largely consistent with dictionary definitions, such as “the physical or mental power or skill needed to do something” (Cambridge Dictionary,

https://dictionary.cambridge.org/us/dictionary/english/ability, accessed 16 April 2024) or “developed skill, competence, or power to do something, especially (in psychology) existing capacity to perform some function, whether physical, mental, or a combination of the two, without further education or training, contrasted with capacity, which is latent ability” (

Oxford Reference,

https://www.oxfordreference.com/search?q=ability&searchBtn=Search&isQuickSearch=true, accessed 16 April 2024). None of the definitions imply innateness or immutability. Other related definitions can be found in Cambridge handbooks on abilities (e.g.,

Kaufman and Sternberg 2019;

Sternberg 2020).

In contrast, an attitude is defined as a developed mindset or approach toward something that is capable of and susceptible to change (

Sternberg 2022). This definition, again, is similar to other standard definitions, such as: “a feeling or opinion about something or someone, or a way of behaving …” (Cambridge Dictionary,

https://dictionary.cambridge.org/us/dictionary/english/attitude, accessed 16 April 2024), or “the way in which a person views and evaluates something or someone (Oxford Reference,

https://www.oxfordreference.com/display/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803095433168, accessed 16 April 2024). Our definition, again, emphasizes the possibility of modifiability. Other related definitions can be found in the literature on attitudes (e.g.,

Banaji and Heiphetz 2010;

Rajecki 1990;

Zanna and Rempel 2008).

From this vantage point, an individual can have an ability, but without the attitude to deploy that ability effectively, or even at all. In some cases, reckless attitudes, such as toward gambling one’s money without setting adequate limits, may undermine the utilization of one’s cognitive abilities. Thus, the ability may remain latent and hence underutilized, misutilized, or even unutilized.

The argument underlying this article is that the deployment of intelligence always requires both intelligence as an ability and intelligence as an attitude. People sometimes have the ability but decide not to use it. Or they may not have so much ability, but they have the attitude to use what ability they have effectively.

Intelligence as an attitude is related to other cognitive, personality, and motivational characteristics, which are discussed in some detail in

Sternberg (

2022). For example, a related construct is the need for cognition (

Cacioppo and Petty 1982;

Cacioppo et al. 1996), but the constructs are not the same. The construct under examination is a basis for whether or how one deploys one’s intelligence, not an underlying need for cognitive functioning in general.

It might seem that how one deploys one’s intelligence is an issue entirely separate from the level of one’s intelligence. At a theoretical level, it is separate. But at a practical level, the level of intelligence can never be fully separated from the deployment of intelligence because performances on the cognitive or other tests used to measure intelligence all represent deployments of intelligence, not pure indicators of intelligence independent of deployment. When one takes a test, one is deploying one’s intelligence. Some people might not care about how they perform on a test, and so do poorly on it. Others might care but not understand the tacit knowledge of test-taking—so-called “test-wiseness”—and so do poorly on the tests. Still others might be very effective in deploying their intelligence, just not on the kinds of conventional tests used to measure intelligence in the West (see, e.g.,

Cole 1998;

Luria 1976;

Sternberg and Preiss 2022). In highly collectivist cultures, the very act of taking a test individually may seem irregular (

Greenfield 1997). And reaction-time tests, or other timed tests, in cultures that view intelligence as comprising slow, deep thought rather than quick, superficial thought, might seem to be counter to what they believe intelligence to be (

Sternberg 2004). In other words, attitudes always mediate any expression of intelligence, including on tests designed to measure intelligence as an ability. When one measures intelligence, an attitude toward the testing process becomes “baked” into the score.

The view of an attitudinal component to intelligence was first proposed by

Sternberg (

2022), but the original proposal did not contain a measure to assess intelligent attitudes. The purpose of this article is to present such a measure and to report on data relevant to validating the measure. This article does not represent a full construct validation, but rather a start toward understanding convergent and discriminant relations between adaptively intelligent attitudes and related constructs. The current research is best viewed as a prologue to a construct validation rather than as a construct validation in itself. There simply is not enough theoretical or empirical work yet to undertake a serious construct validation of attitudinal aspects of intelligence.

The target of our investigation here is what

Sternberg (

2021) has referred to as

adaptive intelligence, which is intelligence as it is involved in adaptation to the environment, a key component of most definitions of intelligence (e.g.,

Gottfredson 1997;

“Intelligence and Its Measurement” 1921).

Sternberg (

2019) introduced the concept of

adaptive intelligence in this journal, and defined it as “

intelligence that is used in order to serve the purpose of biological adaptation, which, for humans, always occurs in, and hence is mediated by, a cultural context” (p. 2). The attitudes measured are those attitudes required for adaptation to the world, which is what we believe intelligence is for. Those attitudes, according to the theory, relate to creative, analytical, practical, wise, and meta-intelligent thinking (where meta-intelligent thinking is the choice to utilize creative, analytical, practical, or wise thinking, according to the circumstances—

Sternberg et al. 2021). Intelligent attitudes are not necessarily specific to any particular situations, such as taking an intelligence test or one of its proxies or performing well in a course in school.

Adaptive intelligence can be measured (

Sternberg et al., forthcoming). Examples are given in

Sternberg (

2021). An example would be knowing how to avoid getting infected by an illness that can rather easily be prevented or knowing how to treat an illness, to the extent possible, so that one works toward getting better (see, e.g.,

Sternberg 2021).

Attitudes toward adaptive intelligence are key to its deployment: some people do not really care all that much about how they adapt to the environment but may care about other things, for example, making money at any cost or taking illegal drugs, which they know are maladaptive and potentially toxic.

Adaptive intelligence is always a person × task × situation interaction (

Sternberg 2021). How well a person adapts will depend upon the tasks they choose or are chosen to confront (e.g., engineering problems versus writing a literary analysis) and the kinds of environmental contexts in which they confront them (e.g., an environment in which one can say what one wants versus an environment in which one can expect to be imprisoned if one says or writes something of which one’s government disapproves). As

Bronfenbrenner and Ceci (

1994) have pointed out, there are always environmental forces that create proximal processes that modify how intelligence and other cognitive abilities develop and manifest themselves.

As an example of effects of proximal processes, countries can degenerate quickly as a result of contextual forces. Criminals can become presidents, prime ministers, and dictators, simply because people do not want to believe the facts that are staring them in the face. One would expect, therefore, that dogmatism and authoritarianism would relate negatively to adaptively intelligent attitudes, whereas openness to experience, need for cognition (to process novel and sometimes unpleasant information), critical thinking, and wisdom to consider information in a balanced way would relate positively to adaptively intelligent attitudes.

Interestingly, perhaps, intelligence as an ability will not necessarily show much, if any, correlation with intelligence as an attitude. Abilities and attitudes are simply different things: the knowledge and skills one possesses, and how one deploys them, are different issues. Oddly, the individual who perhaps best pointed this out was Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. In

Doyle’s (

2003) Sherlock Holmes series of detective stories, Sherlock Holmes had extremely well-developed knowledge and ability for criminological investigation—unusual perceptive, inductive, and deductive reasoning abilities—and in his fictional world, he was an amazing detective. His brother Mycroft Holmes, introduced, for example, in

The Greek Interpreter, was described as considerably more capable than Sherlock Holmes, but did almost nothing with his abilities, preferring to sit around in the Diogenes Club of London, a club for asocial men, each of whom wanted to have nothing to do with the others. Sherlock, in other words, had a profusion of intelligent attitudes, Mycroft, not so many. Perhaps relevant is that Doyle himself, brilliant though he was, was also a spiritualist who had strange beliefs, such as in people’s ability to communicate with the dead. One does not necessarily show in one’s life the abilities and attitudes about which one writes.

Thus, we expected our measure of attitudes relevant to adaptive intelligence to be positively correlated with dispositions and characteristics relevant to the deployment of intelligence—for example, the need for cognition, openness to experience, and wisdom (measured as a disposition). We expected our measure to be negatively correlated with dispositions that tend to close off adaptive intellectual functioning—for example, authoritarianism and dogmatism. And, we expected little or no correlation of our measures with levels of intelligence, as measured by fluid intelligence tests and proxy measures of intelligence (ACT, SAT, two tests used for college admissions in the United States).

4. Discussion

This study suggests that attitudes relevant to the deployment of adaptive intelligence are related to constructs that are also relevant to real-world adaptation, such as the need for cognition, wisdom, or openness to experience, but that they are distinct from fluid intelligence or scholastic aptitude. They represent views on how to deploy intelligence, not levels of intelligence. Someone could have a high level of intelligence but nevertheless choose to deploy it poorly or hardly at all; someone could have a lower level of intelligence but deploy what they have well.

Intelligence as an attitude has been a neglected construct—one that perhaps has not even been defined as a valid part of the construct, which has been viewed solely as an ability. Yet, in the end, what can be observed and measured in some way in the world is always intelligence as filtered through an individual’s attitude about its deployment, whether on a test, in school, or in solving problems in everyday life (

Sternberg 2022). We, therefore, believe that intelligent attitudes need further study. Particular questions that might be asked are (a) how intelligent attitudes either facilitate or impede the display of intelligence as an ability, including on intelligence tests, (b) how students and others as well can be educated to deploy their intelligence more effectively for succeeding in the adaptive tasks they confront, (c) how students and others can be educated to deploy their intelligence more positively to make the world better, and (d) how intelligent attitudes relate to other constructs, such as of abilities and personality.

One might argue that it is hard to compare timed tests of intelligence as an ability with untimed tests of intelligence as an attitude or with personality, dispositions, wisdom, or other attributes that do not generate timed tests with so-called “objectively correct answers”. The mode of testing (power-based or speed-based), in this view, is confounded with the two kinds of constructs (intelligence or everything else). We would argue, however, that this is not a confounding. Many of the theorists of intelligence who have analyzed or produced intelligence tests (see, e.g.,

Cattell 1971;

Carroll 1993;

Ekstrom et al. 1976) have chosen, in our view, mistakenly (see, e.g.,

Sternberg and Grigorenko 2003), to view speed as intrinsic to fluid aspects of intelligence. They also have worked with a construct in which answers can be classified as right or wrong (although only approximately, as inductive reasoning problems do not have truly unique deductively correct answers). Not all intelligence test constructors have taken this point of view (e.g.,

Raven et al. 1992). But in using fluid ability tests derived from theories of intelligence in which mental speed is intrinsic to the definition of intelligence (e.g.,

Ekstrom et al. 1976), the tests must be timed, just as in using tests in which mental speed is not intrinsic to the definitions of the constructs, the tests must be power tests.

In the current view, attitudes always affect test scores. For example, the experience of taking an intelligence-type test or one of its proxies will be different if a high score can be used to earn admission to a prestigious university (especially in a country such as China, where the Gaokao is of utmost importance), versus a situation in which a high score can result in one’s being declared mentally competent (at least, in the United States) and therefore eligible for execution for a capital crime. When the senior author was younger, some 18-year-olds faked low scores on mental tests to avoid being drafted to fight (in Vietnam). The examples do not have to be as extreme. For some people, their scores on standardized tests may determine their future (say, future professional scholars), whereas for other people, the scores will matter little (say, for future professional gardeners). This is not to say that abilities are attitudes, but rather, that scores on ability tests are not pure—they can be influenced by attitudes.

It might be suggested that tests of attitudes somehow could be scored in a way to create objectively better and worse attitudes about specific issues in the world, as might be the case for, say, a test of emotional intelligence. But such a suggestion, which the authors have actually received, is bound to fail. Try telling people that there are “correct” or even “better” and “worse” attitudes about any important issue—abortion, capital punishment, political ideology—and you likely will not get very far.

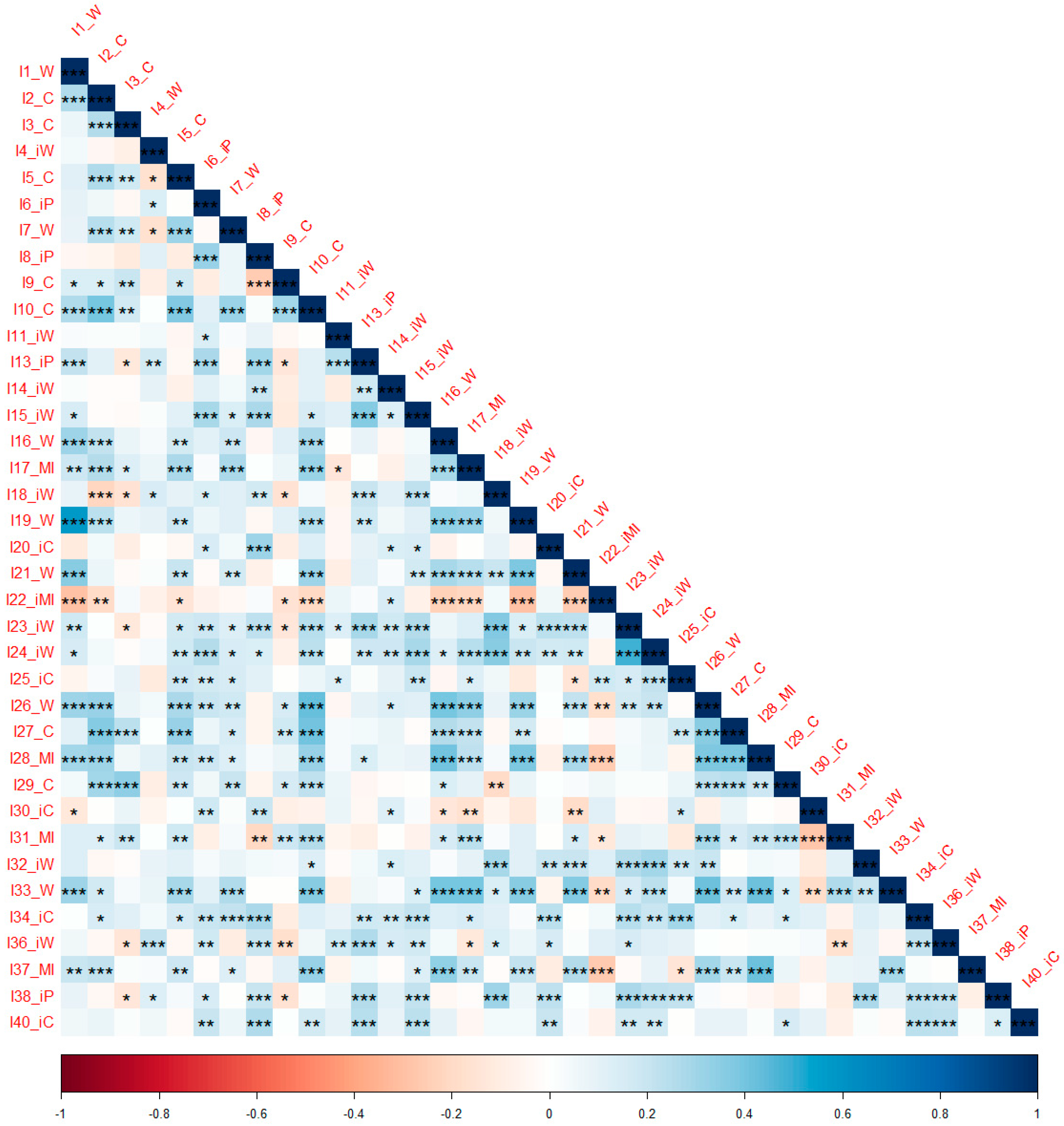

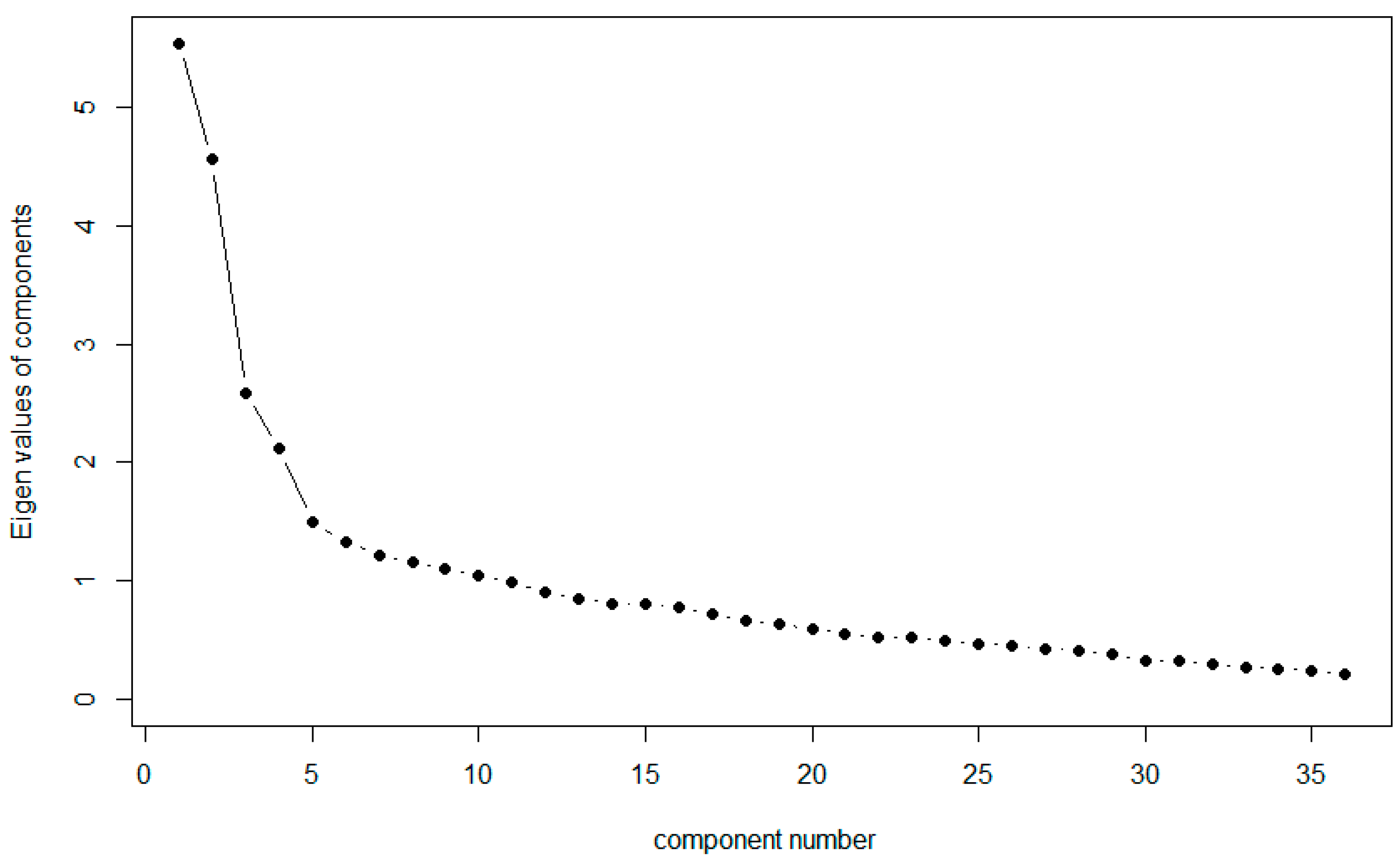

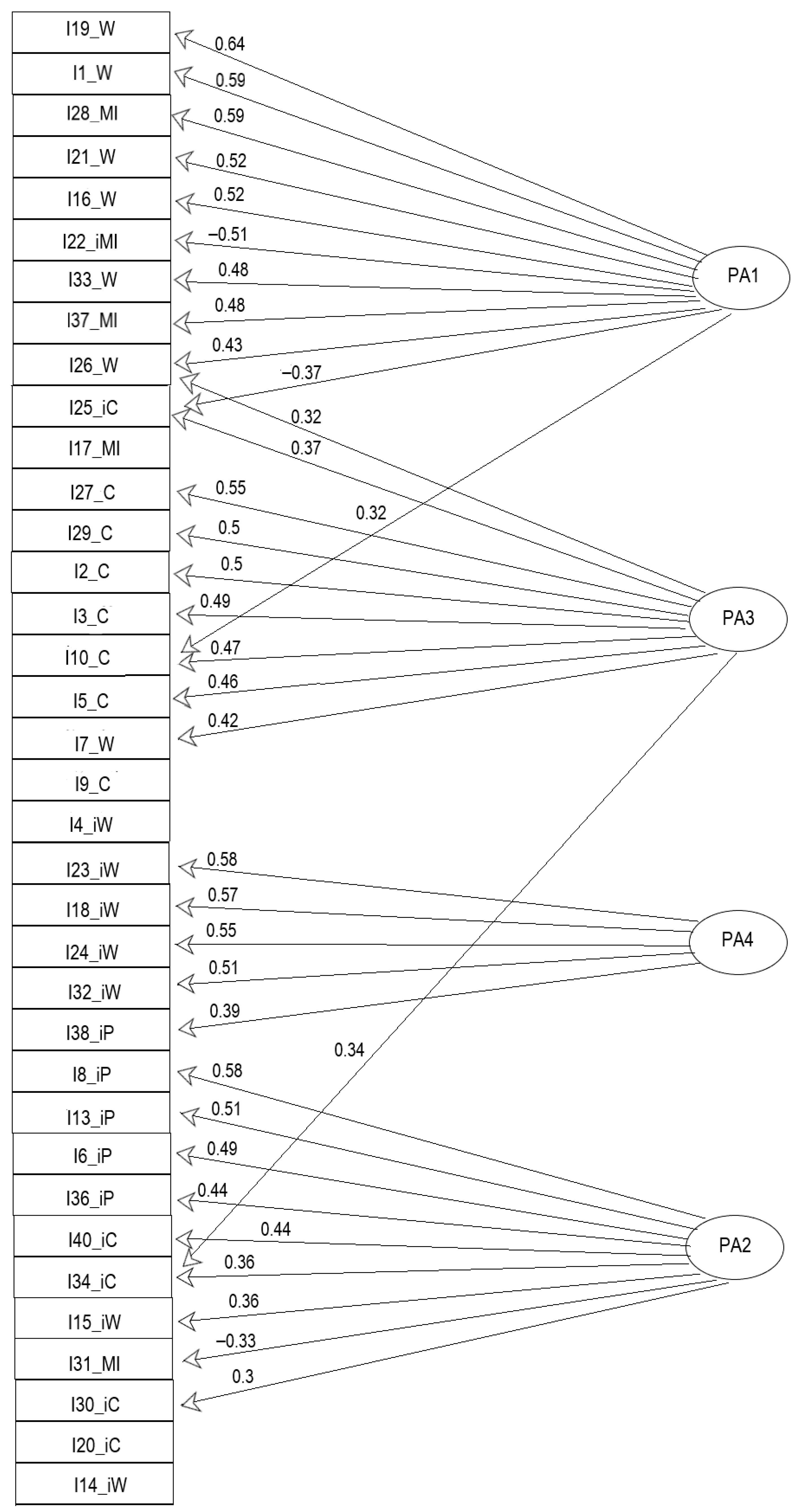

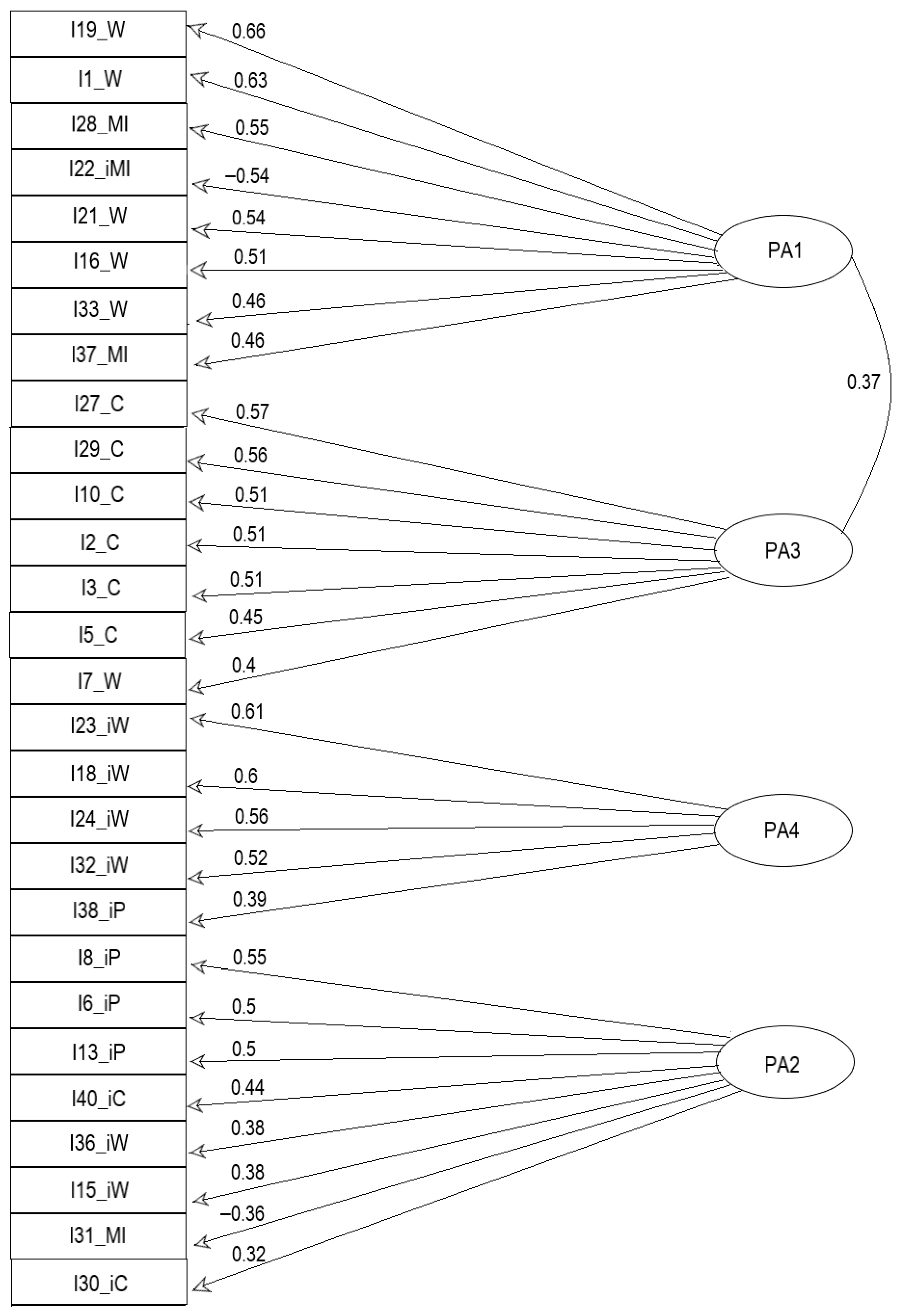

The patterns of correlations and rotated principal components (as well as rotated factors from principal axis factor analyses with oblimin rotation) largely corresponded to our expectations. In general, we found separate factors for intelligent attitudes/dispositions, fluid intellectual abilities, academic ability/achievement, and deference to authority. However, we found that intelligent attitudes correlate positively, to some extent, with one aspect of deference to authority, social desirability, perhaps because intelligent attitudes are intrinsically socially desirable, at least in the US society in which the measurements took place.

The study we conducted had some limitations that must be noted.

First, the sample was from a highly selective university, at least by the standards of the United States. It is the sample that was available to us in the absence of extramural funding of participants and in the presence of a subject pool in our university. The mean SAT score (sum of Reading and Math) was 1105 in 2023 (

https://wisevoter.com/state-rankings/sat-scores-by-state/#average-sat-scores, accessed on 2 April 2024; our mean was 1461. Results might have been different in an intellectually more diverse sample. That said, our concern was not with the aspect of intelligence as an ability measured by the SAT, but rather with (adaptive) intelligence as attitude, and it is not clear how different our sample would have been in this respect from one with different SAT scores.

Second, we present this work only as a single study with just short of 200 (N = 187) participants. In future work, more participants would need to be tested, ideally, in a variety of cultures. Moreover, our participants were college students, generally in the age range of 18–22, and further work would be needed to extend the age range to see whether results are the same across age groups.

Third, however modifiable abilities may or may not be, attitudes certainly are at least somewhat modifiable. So it may be that, with intervention, perhaps even fairly rudimentary intervention, attitudes could be changed and made more favorable for positive deployment of adaptive intelligence. That remains to be seen.

Fourth, our measure was a typical-performance Likert-scale assessment. There is always a chance that at least some participants answered in ways they thought the experimenters would want to hear. We examined the distributions of scores on the Social Desirability and Self-Deceptive Enhancement subscales to investigate this possibility. We found normal distributions for both and no high-end single or multiple outliers that would suggest people were faking. Indeed, the data were collected anonymously and for course credit simply by virtue of participation, so there was no obvious incentive to fake.

We believe that the notion of adaptively intelligent attitudes is an important one in today’s world and has important implications for understanding intelligence as it applies in everyday life. It is important because many people, even intelligent ones, fail sufficiently to deploy their intelligence, and some who do deploy it may deploy it in ways that are not conducive to adaptation. For example, political leaders whose only goal is to stay in power, or who start wars to achieve internal cohesion, are not deploying their intelligence in an optimal way. We plan to investigate further light and dark deployments of intelligence, and hope that in conjunction with this work, we can better understand how to encourage people to deploy their intelligence in the interest of making the world a better place.

We emphasize that our goal is

not to suggest that intelligence is merely a set of attitudes rather than a set of abilities. We do not interpret either our theoretical proposals or empirical data as suggesting that any particular theory of intelligence, or theories of intelligence, in general, are in need of correction. We simply did not address the issue of the adequacy of any particular psychometric, cognitive, biological, cultural, or other theory (see reviews of theories in

Sternberg 2020). Rather, we have suggested that when intelligence is viewed, as it historically has been, in terms of adaptation to the environment (

Binet and Simon 1916;

Gottfredson 1997;

“Intelligence and Its Measurement” 1921;

Spearman 1923;

Wechsler 1940), attitudes matter as well as abilities because attitudes are largely, although not exclusively, what determine how intelligence is deployed. Understanding intelligent attitudes can help close the conceptual as well as predictive gaps between intelligence as conceptualized, measured, and successfully deployed in the world. We, therefore, suggest that intelligent attitudes be explored seriously as a way of better understanding how intelligence functions in the everyday world, not just in controlled and sometimes contrived situations.

This work was described at the beginning of the article as a preliminary to a construct validation rather than as itself a construct validation of the notion of intelligence as having an attitudinal component. What might future research look like that would begin a more advanced process of construct validation? It would seek to establish a nomological network for intelligence as an attitude (

Cronbach and Meehl 1955) and indicate whether the conceptual differences among constructs are matched by statistical differences.

First, one could examine a broader range of intellectual abilities. The abilities are cognitive, and other sets of developed skills, as opposed to attitudes toward the use of those skills, could be explored. A first step would be to compare intelligence as an attitude to more of the cognitive abilities that comprise intelligence, at minimum, crystallized, as well as the fluid ability that was measured here (see

Cattell 1971) and other abilities described in

Carroll’s (

1993) conceptualization of the Cattell–Horn–Carroll (

McGrew 2009) conception. These other abilities might include various speed, perceptual, and memory factors that were not considered here.

Second, one could examine rational thinking. One has a certain level of ability to think rationally, but attitudinally, one may or may not choose to use this ability. Often, when problems are high-stakes or are emotionally laden, people do not think as rationally as they are capable of thinking because they are too swayed by answers they want rather than answers that would be, from a rational point of view, best. Rational thinking, as an ability, can yield tests that have more and less rational answers, as objectively defined, and as have been assessed by Stanovich and colleagues. A second step, therefore, could be to compare intelligence as an attitude to aspects of rational thinking, as studied by Stanovich and his colleagues (

Stanovich 2009,

2021;

Stanovich and West 2000;

Stanovich et al. 2013).

Third, one could examine personality traits. Personality traits are fairly stable characteristics of how people react to situations, in general, whereas attitudes are more malleable and are thoughts relevant to how people will react in particular situations. A third step, therefore, could be to compare intelligence as an attitude to personality as conceptualized in the five-factor theory—the so-called “OCEAN” theory specifying as factors openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism (

McCrae and Costa 2008;

Poropat 2009).

Fourth, one could examine motivation. Motivation is the desire or willingness of someone to do something or a set of things. Attitudes may lead to motivations, as when an individual who has conservative (or liberal) attitudes is motivated to vote for a political candidate with similar attitudes. A fourth step, therefore, could be to compare intelligence as an attitude to aspects of motivation, for example, in

Ryan and Deci’s (

2017) self-determination theory of motivation. One would then be examining how intelligence as an attitude compares to needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness.

Fifth, one could look at future behavior. A fifth and perhaps most important step could be to relate intelligence as an attitude to future performances in the world—in school, on the job, or in one’s personal life (such as health maintenance, marital success, or longevity).

Intelligence tests represent one deployment of intelligence. But for the emotionally charged, high-stakes, and sometimes even life-threatening situations people confront in their lives, intelligent attitudes can make the difference between success and failure in adaptation. We therefore recommend that they be considered, as well as abilities, in our understanding of how to conceptualize, measure, and teach for intelligence.