Intelligence, Personality and Tolerance of Ambiguity

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Two Theories

1.2. Other Traits

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.3. Procedure

3. Results

Sex Differences

4. Correlations

5. Regressions

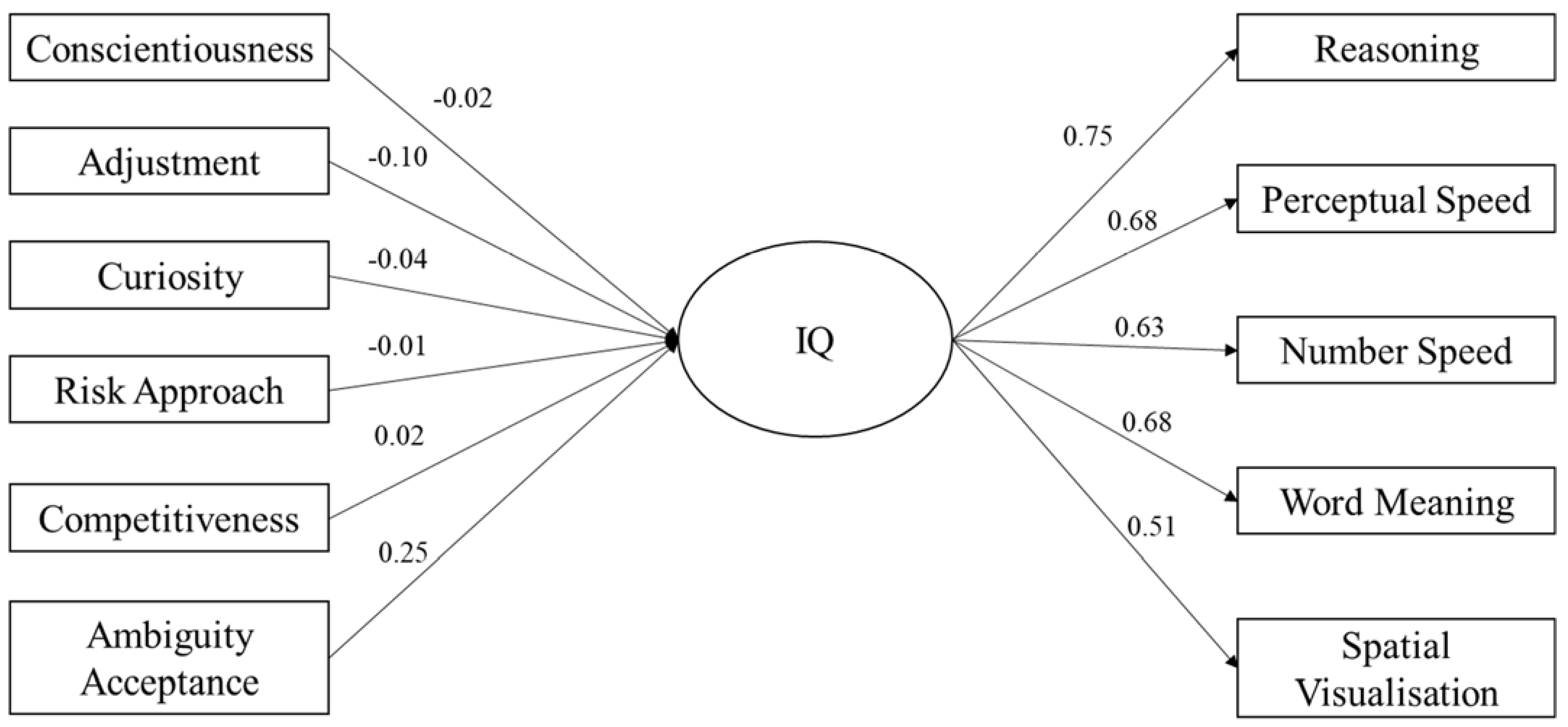

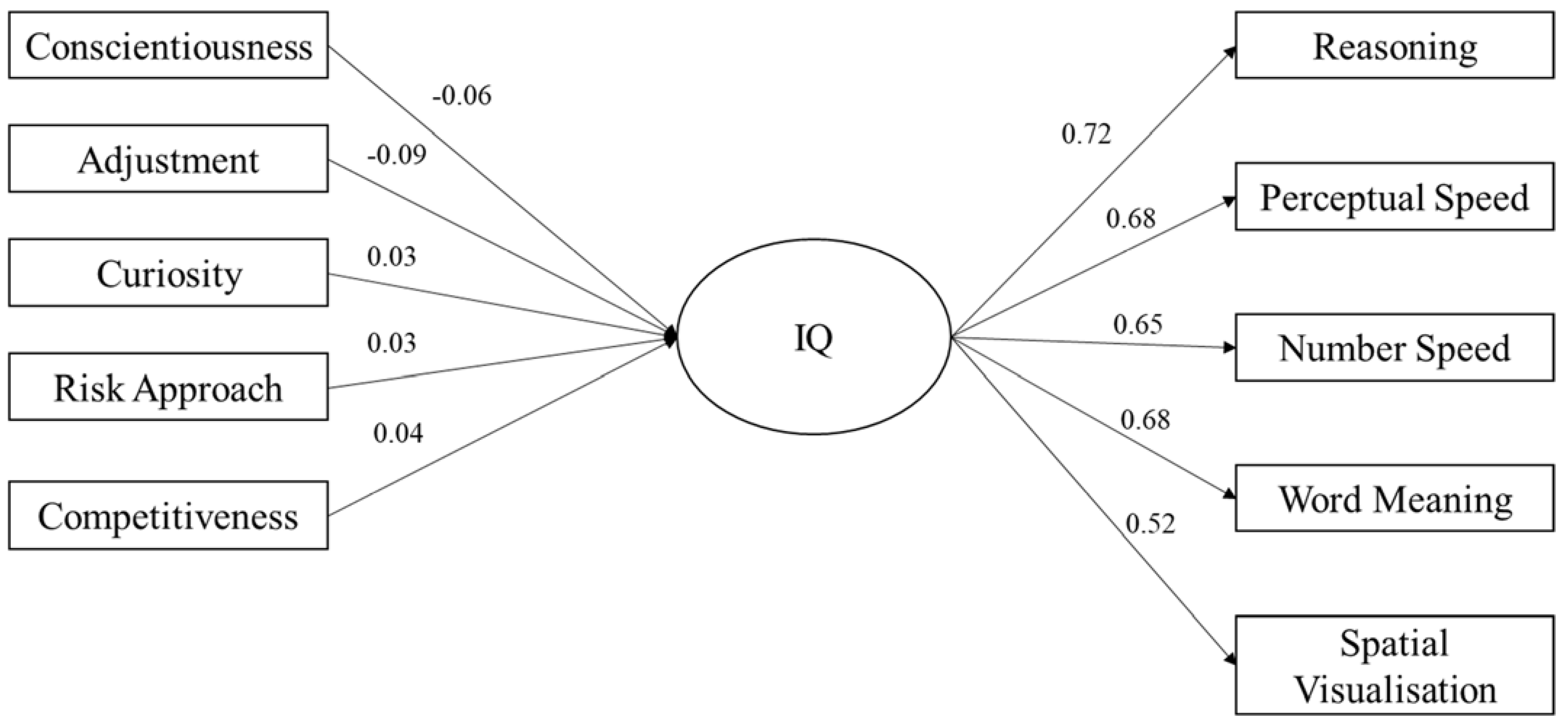

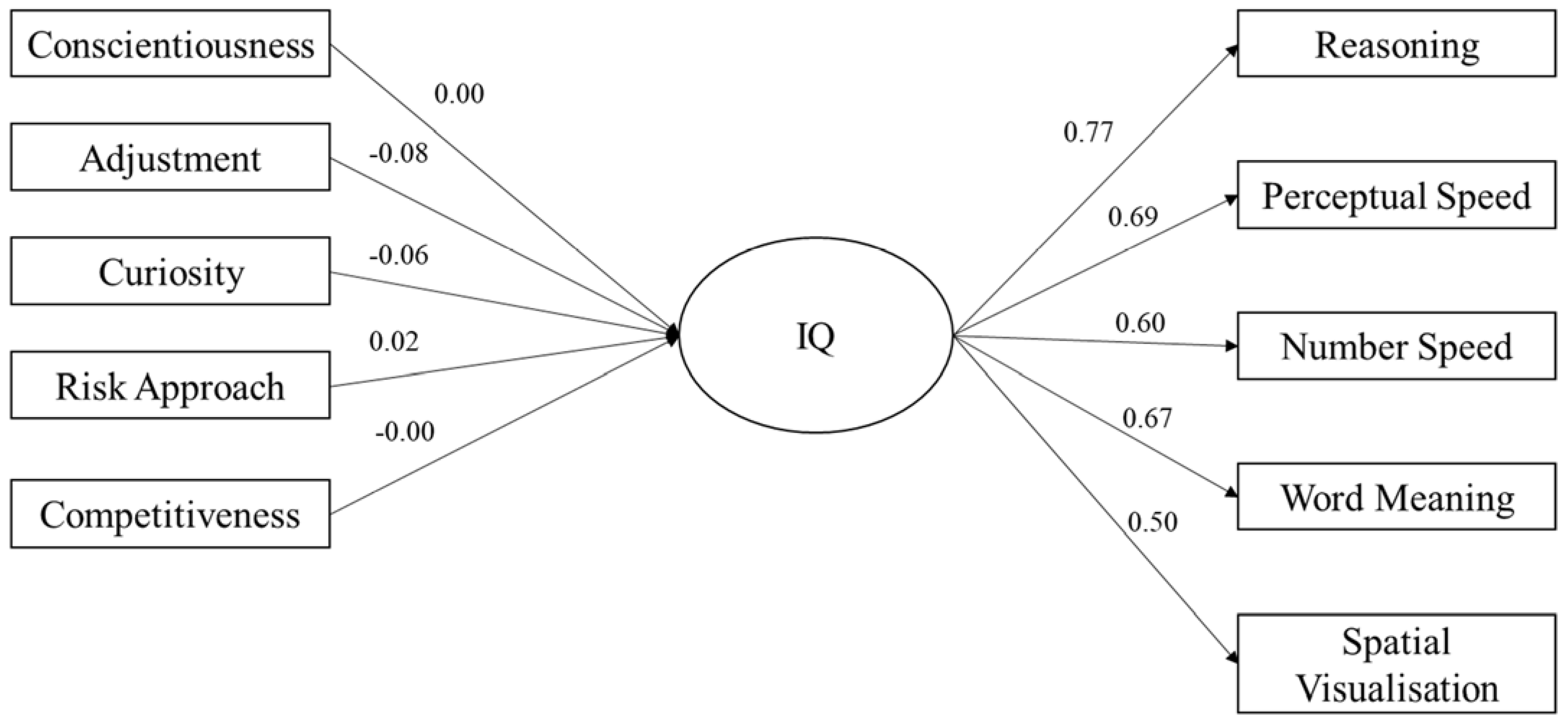

6. Structural Equation Model

7. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ackerman, Phillip L., and Eric D. Heggestad. 1997. Intelligence, personality, and interests: Evidence for overlapping traits. Psychological Bulletin 121: 219–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anglim, Jeromy, Patrick D. Dunlop, Serena Wee, Sharon Horwood, Joshua K. Wood, and Andrew Marty. 2022. Personality and intelligence: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin 148: 301–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, Elizabeth J., Ian J. Deary, Martha C. Whiteman, F. Gerry R. Fowkes, Nancy L. Pedersen, Patrick Rabbitt, Nuala Bent, and Lynn McInnes. 2002. Relationships between ability and personality: Does intelligence contribute positively to personal and social adjustment? Personality and Individual Differences 32: 1391–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauducel, André, Detlev Liepmann, Jörg Felfe, and Wim Nettelnstroth. 2007. The Impact of Different Measurement Models for Fluid and Crystallized Intelligence on the Correlation with Personality Traits. European Journal of Psychological Assessment 23: 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bédard, Marc-André, and Yann Le Corff. 2020. Intelligence and personality: A replication and extension study of the association between intelligence and personality aspects. Journal of Individual Differences 41: 124–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caligiuri, Paula M., Rick R. Jacobs, and James L. Farr. 2000. The Attitudinal and Behavioral Openness Scale: Scale development and construct validation. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 24: 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattell, Raymond Bernard. 1971. Abilities: Their Structure, Growth, and Action. Washington, DC: Houghton Mifflin. [Google Scholar]

- Caulfield, Marie, Kathryn Andolsek, Douglas Grbic, and Lindsay Roskovensky. 2014. Ambiguity tolerance of students matriculating to US medical schools. Academic Medicine 89: 1526–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamorro-Premuzic, Tomas, and Adrian Furnham. 2004. A possible model for explaining the personality-intelligence interface. British Journal of Psychology 95: 249–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamorro-Premuzic, Tomas, and Adrian Furnham. 2006. Intellectual competence and the intelligent personality: A third way in differential psychology. Review of General Psychology 10: 251–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamorro-Premuzic, Tomas, and Adrian Furnham. 2008. Personality, intelligence and approaches to learning as predictors of academic performance. Personality and Individual Differences 44: 1596–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colom, Roberto, Doreen Bensch, Kai T. Horstmann, Caroline Wehner, and Matthias Ziegler. 2019. Special Issue “The Ability–Personality Integration”. Journal of Intelligence 7: 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corazza, Giovanni Emanuele, and Todd Lubart. 2021. Intelligence and Creativity: Mapping Constructs on the Space-Time Continuum. Journal of Intelligence 9: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuppello, Stephen, Luke Treglown, and Adrian Furnham. 2023a. Are they sharper at the top? Intelligence, Personality and Management level. Acta Psychologia. [Google Scholar]

- Cuppello, Stephen, Luke Treglown, and Adrian Furnham. 2023b. Personality and Management Level: Traits that get you to the top. Personality and Individual Difference 206: 112108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dann, Peter. 2015. The General Intelligence Assessment (GIA) Technical Manual. London: Thomas International Limited. [Google Scholar]

- de Vries, Henderika Herie. 2021. Tolerance of Ambiguity. In The Palgrave Encyclopedia of the Possible. Edited by Vlad Petre Glaveanu. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Demetriou, Andreas, George Spanoudis, and Hudson Golino. 2018. gP for What is Common between Developing Intelligence and Personality: Response to the Commentators. Journal of Intelligence 6: 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeYoung, Colin G. 2011. Intelligence and personality. In The Cambridge Handbook of Intelligence. Edited by Robert J. Sternberg and Scott B. Kaufman. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 711–37. [Google Scholar]

- DeYoung, Colin G. 2020. Intelligence and personality. In The Cambridge Handbook of Intelligence, 2nd ed. Edited by Robert J. Sternberg. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 1011–47. [Google Scholar]

- Dissou, G. 2003. The Identification of High Flyer Traits. Unpublished Doctoral thesis, University of London, London, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck, Hans J. 1998. Intelligence: A New Look. Piscataway: Transaction Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Furnham, Adrian. 2005. Self-estimated intelligence, psychometric intelligence and personality. Psychologia: An International Journal of Psychology in the Orient 48: 182–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furnham, Adrian. 2017a. Ambiguity Intolerance. In Oxford Encyclopedia of Health and Risk Message Design and Processing. Edited by Roxanne Parrott. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 99–117. [Google Scholar]

- Furnham, Adrian. 2017b. Personality and Intelligence in a High Ability Sample. Psychology 8: 1355–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furnham, Adrian. 2020. Typical Intellectual Engagement (TEI). In Encyclopaedia of Personality and Individual Differences. Edited by Virgil Zeigler-Hill and Todd K. Shackelford. Cham: Springer, pp. 3059–62. [Google Scholar]

- Furnham, Adrian, and Joseph Marks. 2013. Tolerance of Ambiguity: A review of the recent literature. Psychology 4: 717–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furnham, Adrian, and Luke Treglown. 2018. High potential personality and intelligence. Personality and Individual Differences 128: 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furnham, Adrian, and Luke Treglown. 2021a. Sex differences in personality scores on six scales: Many significant, but mostly small, differences. Current Psychology 42: 3449–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furnham, Adrian, and Luke Treglown. 2021b. The Dark Side of High-Fliers: The Dark Triad, High-Flier Traits, Engagement, and Subjective Success. Frontiers in Psychology 12: 647676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furnham, Adrian, and Sylvia Impellizzeri. 2021. The Personality and Motivation of “Quants”: The Maths Geniuses of Wall Street. Journal of Financial Management, Markets and Institutions 9: 2150002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gignac, Gilles E. 2015. Raven’s is not a pure measure of general intelligence: Implications for g factor theory and the brief measurement of g. Intelligence 52: 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gow, Alan J., Martha C. Whiteman, Alison Pattie, and Ian J. Deary. 2005. The personality-intelligence interface: Insights from an ageing cohort. Personality and Individual Differences 39: 751–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris-Watson, Alexandra M., Mei-Chuan Kung, Michael C. Tocci, Anthony S. Boyce, Jeff A. Weekley, Nigel Guenole, and Nathan T. Carter. 2022. The Interaction Between Conscientiousness and General Mental Ability: Support for a Compensatory Interaction in Task Performance. Journal of Business and Psychology 37: 855–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, Daire, Joseph Coughlan, and Michael Mullen. 2008. Evaluating model fit: A synthesis of the structural equation modelling literature. Paper present at the 7th European Conference on Research Methodology for Business and Management Studies, London, UK, June 19–20; pp. 195–200. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Litze, and Peter M. Bentler. 1998. Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods 3: 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irvine, S. H., P. L. Dann, and J. D. Anderson. 1990. Towards a theory of algorithm-determined cognitive test construction. British Journal of Psychology 81: 173–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johann, Verena E., and Julia Karbach. 2022. The relations between personality, components of executive functions, and intelligence in children and young adults. Psychological Research 86: 1904–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Wendy, Jan te Nijenhuis, and Thomas J. Bouchard, Jr. 2008. Still just 1 g: Consistent results from five test batteries. Intelligence 36: 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsaros, Kleanthis K., Athanasios N. Tsirikas, and Christos S. Nicolaidis. 2014. Managers’ workplace attitudes, tolerance of ambiguity and firm performance: The case of Greek banking industry. Management Research Review 37: 442–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, Theresa J. 2005. Psychological Testing: A Practical Approach to Design and Evaluation. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Kretzschmar, André, Lisa Wagner, Fabian Gander, Jennifer Hofmann, René T. Proyer, and Willibald Ruch. 2022. Character strengths and fluid intelligence. Journal of Personality 90: 1057–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kretzschmar, André, Marion Spengler, Anna-Lena Schubert, Ricarda Steinmayr, and Matthias Ziegler. 2018. The Relation of Personality and Intelligence—What Can the Brunswik Symmetry Principle Tell Us? Journal of Intelligence 6: 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, Chloe, R. Michael Bagby, Bruce G. Pollock, and Lena Quilty. 2023. Five-Factor Model and DSM-5 Alternative Model of Personality Disorder Profile Construction: Associations with Cognitive Ability and Clinical Symptoms. Journal of Intelligence 11: 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leikas, Sointu, Seppo Mäkinen, Jan-Erik Lönnqvist, and Markku Verkasalo. 2009. Cognitive ability×Emotional stability interactions on adjustment. European Journal of Personality 23: 329–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohman, David F., and Joni M. Lakin. 2011. Intelligence and Reasoning. In The Cambridge Handbook of Intelligence. Edited by Robert J. Sternberg and Scott Barry Kaufman. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 419–41. [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum, Robert C., Michael W. Browne, and Hazuki M. Sugawara. 1996. Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychological Methods 1: 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macke, Lindsey, Flor de León, Tobias Hermansson, and Petri Kajonius. 2022. An Investigation of the Relationship between Personality, Cognitive Ability, and Work Engagement in Intellectually Gifted Individuals. Journal of Intelligence 10: 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacRae, Ian, and Adrian Furnham. 2020. A Psychometric Analysis of the High Potential Trait Inventory (HPTI). Psychology 11: 1125–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Major, Jason T., Wendy Johnson, and Ian J. Deary. 2014. Linear and Nonlinear Associations Between General Intelligence and Personality in Project TALENT. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 106: 638–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinsen, O. 2023. Personality Traits as Predictors of Selection, Deselection, and Rejection of Leadership Roles in the Armed Forces. Unpublished paper. [Google Scholar]

- Moutafi, Joanna, Adrian Furnham, and Laurence Paltiel. 2004. Why is conscientiousness negatively correlated with intelligence? Personality and Individual Differences 37: 1013–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, Aja L., Wendy Johnson, Matt McGue, and William G. Iacono. 2014. How are conscientiousness and cognitive ability related to one another? A re-examination of the intelligence compensation hypothesis. Personality and Individual Differences 70: 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rammstedt, Beatrice, Clemens M. Lechner, and Daniel Danner. 2018. Relationships between personality and cognitive ability: A facet-level analysis. Journal of Intelligence 6: 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reeve, Charlie L., and Nikki Blacksmith. 2009. Identifying g: A review of current factor analytic practices in the science of mental abilities. Intelligence 37: 487–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, Charlie L., Rustin D. Meyer, and Silvia Bonaccio. 2006. Intelligence–personality associations reconsidered: The importance of distinguishing between general and narrow dimensions of the intelligence. Intelligence 34: 387–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schermer, Julie Aitken, Georg Krammer, Richard D. Goffin, and Michael D. Biderman. 2020. Using the 16PF to Test the Differentiation of Personality by Intelligence Hypothesis. Journal of Intelligence 8: 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teodorescu, Alexandra, Adrian Furnham, and Ian MacRae. 2017. Trait correlates of success at work. International Journal of Selection and Assessment 25: 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treglown, Luke, and Adrian Furnham. 2020. Birds of a feather work together: The role of emotional intelligence and cognitive ability in workplace interaction and advice networks. Personality and Individual Differences 158: 109833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treglown, Luke, and Adrian Furnham. 2022. Age, Sex, Education, EQ, IQ and Management Level: A Study from Great Britain. Journal of General Management 48: 320–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Stumm, Sophie, and Phillip L. Ackerman. 2013. Investment and intelligence: A review and meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin 139: 841–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Stumm, Sophie. 2018. Better open than intellectual: The benefits of investment personality traits for learning. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 44: 562–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willoughby, Emily A., Yuri Kim, James J. Lee, and Colin G. DeYoung. 2023. The Construct Validity of Intellect and Openness as Distinct Aspects of Personality through Differential Associations with Reaction Time. Journal of Intelligence 11: 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, Paul, and Paul Englert. 2009. Intelligence compensation theory: A critical examination of the negative relationship between conscientiousness and fluid and crystallised intelligence. Australasian Journal of Organisational Psychology 2: 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, Stephen A., Daniel P. Hinton, Sophie von Stumm, and James Bellman-Jeffreys. 2019. Personality and intelligence: Examining the associations of investment-related personality traits with general and specific intelligence. European Journal of Psychological Assessment 35: 206–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeidner, Moshe, and Gerald Matthews. 2000. Intelligence and personality. In Handbook of Intelligence. Edited by Robert Sternberg. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 581–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, Matthias, Erik Danay, Moritz Heene, Jens Asendorpf, and Markus Bühner. 2012. Openness, fluid intelligence, and crystallized intelligence: Toward an integrative model. Journal of Research in Personality 46: 173–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Test | Description | Format | Length (Minutes) | Abilities Tested |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VR | Evaluates problem-solving abilities (i.e., capacity to reason, make inferences, draw conclusions) by testing simple deductive verbal reasoning skills | Problem-solving task: After reading a statement (e.g., Jack is taller than Jill), participants need to answer a related question (e.g., Who is shorter? Jack or Jill?). | 5 | Fluid and crystallised intelligence |

| PS | Measures visual checking skills (i.e., ability to identify and report on similarities/differences, details, and errors) by testing semantic perception and encoding | Letter-matching task: Participants need to identify matching letters between rows of capital and lower case letters (e.g., ADGK/afgm). | 4.5 | Broad cognitive speed |

| NS | Assesses overall numeracy (i.e., capacity to process numerical information, perform mental calculations, and reason with quantitative concepts) | Number task: Out of three numbers, participants need to identify which number is numerically farther from the others (e.g., 2, 9, 5). | 2 | Fluid intelligence and memory |

| WM | Evaluates vocabulary and word-related knowledge (i.e., ability to comprehend large numbers of words and identify words with similar or opposite meanings) | Semantic word task: Participants are shown three words (e.g., up, down, street) and need to specify which word is not related to the others (e.g., street). | 2.5 | Mainly crystallised intelligence |

| SV | Tests mental visualisation skills (i.e., ability to visualise concepts and objects and mentally rotate and manipulate shapes and symbols) | Symbol task: Participants need to identify pairs of identical symbols (when symbols have been rotated and/or presented as mirror images of each other). | 2 | Fluid intelligence and visual perception |

| M | SD | F | Cohen’s d | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conscientiousness | Female | 65.46 | 15.69 | 14.11 | −.13 |

| Male | 67.41 | 15.29 | |||

| Adjustment | Female | 64.89 | 16.28 | 5.50 | −.08 |

| Male | 66.15 | 15.71 | |||

| Curiosity | Female | 60.84 | 13.16 | 1.12 | .04 |

| Male | 60.39 | 12.43 | |||

| Risk Approach | Female | 58.15 | 13.35 | 108.44 | −.35 |

| Male | 62.68 | 12.68 | |||

| Ambiguity Acceptance | Female | 48.49 | 12.10 | 20.20 | −.15 |

| Male | 50.29 | 11.85 | |||

| Competitiveness | Female | 46.96 | 13.80 | 67.84 | −.28 |

| Male | 50.68 | 13.18 | |||

| Overall IQ | Female | 51.05 | 11.02 | 5.06 | −.08 |

| Male | 51.92 | 11.86 | |||

| Reasoning | Female | 40.77 | 8.77 | 22.02 | .16 |

| Male | 39.36 | 9.08 | |||

| Perceptual | Female | 43.02 | 6.55 | 2.20 | .05 |

| Male | 42.69 | 6.59 | |||

| Numbers | Female | 13.36 | 5.53 | 85.75 | −.32 |

| Male | 15.26 | 6.42 | |||

| Words | Female | 30.31 | 5.61 | 1.65 | .04 |

| Male | 30.07 | 5.68 | |||

| Spatial | Female | 9.57 | 5.10 | 65.26 | −.27 |

| Male | 10.98 | 5.22 |

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | 1.64 | .48 | ||||||||||||||

| 2. Age | 38.57 | 10.75 | .19 *** | |||||||||||||

| 3. Conscient. | 66.71 | 15.46 | .06 *** | .05 ** | ||||||||||||

| 4. Adjust. | 65.70 | 15.93 | .04 * | .07 *** | .41 *** | |||||||||||

| 5. Curiosity | 60.55 | 12.70 | −.02 | −.05 ** | .30 *** | .21 *** | ||||||||||

| 6. Risk Appro. | 61.05 | 13.11 | .17 *** | .12 *** | .54 *** | .45 *** | .40 *** | |||||||||

| 7. Amb. Accept. | 49.64 | 11.97 | .07 *** | .15 *** | .15 *** | .33 *** | .31 *** | .37 *** | ||||||||

| 8. Competitive. | 49.34 | 13.52 | .13 *** | −.21 *** | .31 *** | −.03 * | .11 *** | .27 *** | .00 | |||||||

| 9. Overall IQ | 51.61 | 11.58 | .04 * | −.12 *** | −.03 | −.04 * | .01 | .02 | .18 *** | .02 | ||||||

| 10. Reason | 39.87 | 9.00 | −.08 *** | −.16 *** | −.03 | −.02 | .00 | −.01 | .14 *** | .00 | .79 *** | |||||

| 11. Percept | 42.81 | 6.58 | −.02 | −.15 *** | −.00 | .00 | .01 | .03 * | .09 *** | .03 | .77 *** | .52 *** | ||||

| 12. Number | 14.58 | 6.18 | .15 *** | −.16 *** | −.01 | −.03 | −.02 | .02 | .14 *** | .10 *** | .73 *** | .45 *** | .42 *** | |||

| 13. Words | 30.16 | 5.66 | −.02 | .09 *** | −.05 ** | −.07 *** | .02 | −.01 | .18 *** | −.08 *** | .74 *** | .55 *** | .46 *** | .39 *** | ||

| 14. Spatial | 10.47 | 5.22 | .13 *** | −.03 | −.00 | −.02 | .02 | .04 ** | .11 *** | .01 | .63 *** | .34 *** | .37 *** | .41 *** | .32 *** |

| Overall IQ | Reasoning | Numbers | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | Beta | t | B | SE | Beta | t | B | SE | Beta | t | |||||

| Gender | 1.27 | .39 | .05 | 3.23 ** | −.99 | .31 | −.05 | −3.23 ** | 2.19 | .21 | .17 | 10.60 *** | ||||

| Age | −.18 | .02 | −.17 | −9.92 *** | −.16 | .01 | −.19 | −11.02 *** | −.12 | .01 | −.21 | −12.88 *** | ||||

| Conscient. | .00 | .02 | .00 | 0.04 | −.00 | .01 | −.00 | −0.10 | .00 | .01 | .01 | 0.33 | ||||

| Adjust. | −.08 | .01 | −.11 | −5.60 *** | −.04 | .01 | −.06 | −3.38 *** | −.03 | .01 | −.07 | −3.84 *** | ||||

| Curiosity | −.05 | .02 | −.06 | −3.30 *** | −.04 | .01 | −.06 | −3.40 *** | −.04 | .01 | −.08 | −4.35 *** | ||||

| Risk Appro. | .02 | .02 | .02 | 0.99 | .01 | .02 | .01 | 0.49 | −.00 | .01 | −.01 | −0.45 | ||||

| Amb. Accept. | .23 | .02 | .24 | 13.67 *** | .15 | .01 | .20 | 11.48 *** | .11 | .01 | .21 | 11.87 *** | ||||

| Competitive. | −.02 | .02 | −.03 | −1.55 | −.02 | .01 | −.03 | −1.51 | .02 | .01 | .04 | 2.01 | ||||

| Adjusted R2 | .066 | .061 | .093 | |||||||||||||

| F | 34.815 | 32.058 | 50.131 | |||||||||||||

| p | .000 | .000 | .000 | |||||||||||||

| Words | Spatial | |||||||||||||||

| B | SE | Beta | t | B | SE | Beta | t | |||||||||

| Gender | −.40 | .19 | −.03 | −2.08 * | 1.49 | .18 | .14 | 8.26 *** | ||||||||

| Age | .03 | .01 | .06 | 3.59 *** | −.04 | .01 | −.08 | −4.70 *** | ||||||||

| Conscient. | −.00 | .01 | −.00 | −0.11 | .00 | .01 | .01 | 0.41 | ||||||||

| Adjust. | −.05 | .01 | −.14 | −7.54 *** | −.03 | .01 | −.08 | −4.18 *** | ||||||||

| Curiosity | −.01 | .01 | −.01 | −0.59 | −.01 | .01 | −.02 | −0.97 | ||||||||

| Risk Appro. | −.00 | .01 | −.01 | −0.34 | .01 | .01 | .03 | 1.44 | ||||||||

| Amb. Accept. | .11 | .01 | .23 | 12.90 *** | .06 | .01 | .13 | 7.33 *** | ||||||||

| Competitive. | −.03 | .01 | −.06 | −3.37 *** | −.02 | .01 | −.04 | −2.12 * | ||||||||

| Adjusted R2 | .061 | .035 | ||||||||||||||

| F | 31.911 | 18.446 | ||||||||||||||

| p | .000 | .000 | ||||||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cuppello, S.; Treglown, L.; Furnham, A. Intelligence, Personality and Tolerance of Ambiguity. J. Intell. 2023, 11, 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence11060102

Cuppello S, Treglown L, Furnham A. Intelligence, Personality and Tolerance of Ambiguity. Journal of Intelligence. 2023; 11(6):102. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence11060102

Chicago/Turabian StyleCuppello, Stephen, Luke Treglown, and Adrian Furnham. 2023. "Intelligence, Personality and Tolerance of Ambiguity" Journal of Intelligence 11, no. 6: 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence11060102

APA StyleCuppello, S., Treglown, L., & Furnham, A. (2023). Intelligence, Personality and Tolerance of Ambiguity. Journal of Intelligence, 11(6), 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence11060102