A Proactive Explainable Artificial Neural Network Model for the Early Diagnosis of Thyroid Cancer

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Studies

2.1. AI-Based Studies on the Early Diagnosis of Thyroid Cancer

2.2. Applications of EAI in Diagnosis and Surgery

3. Materials and Methods

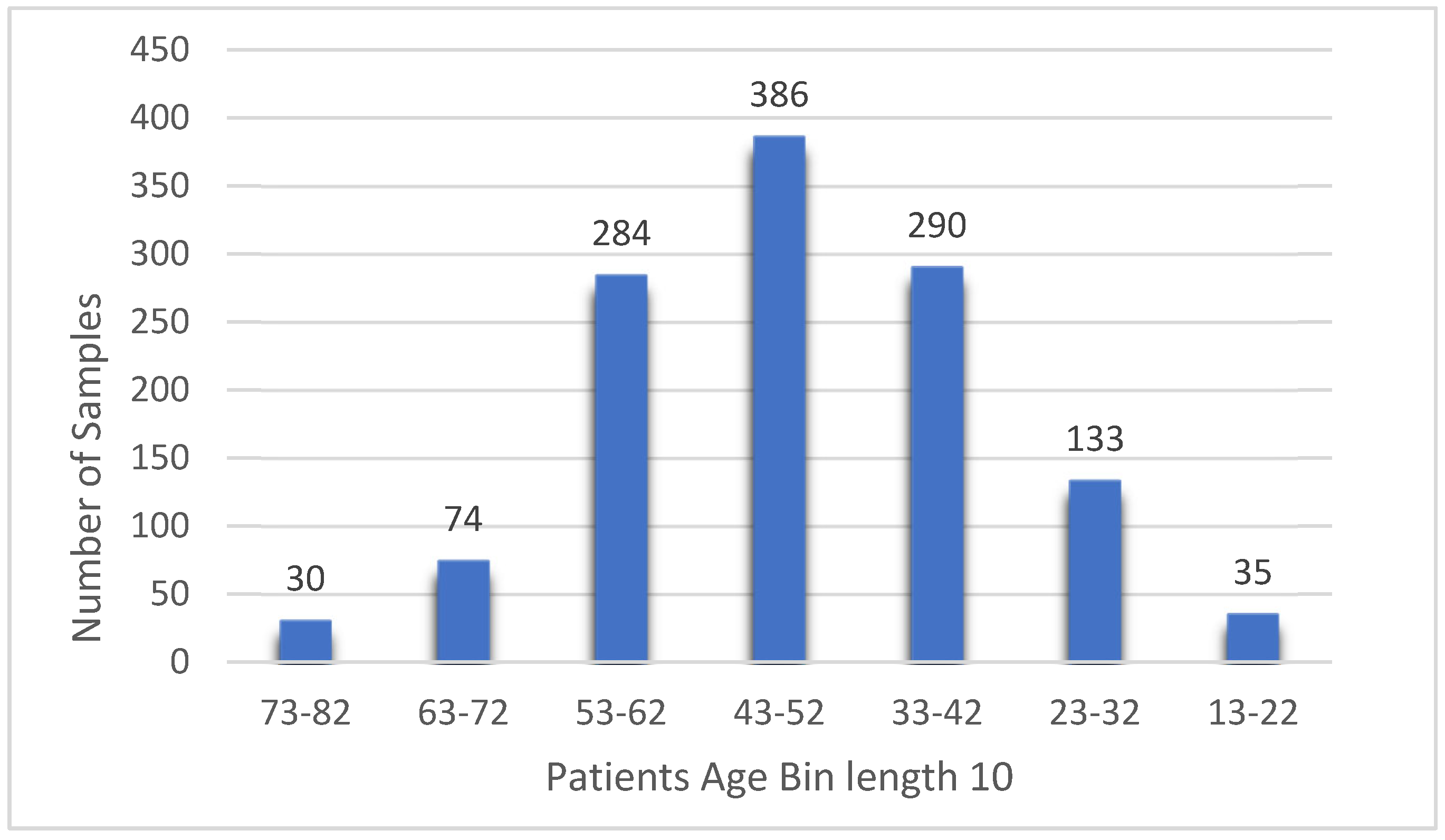

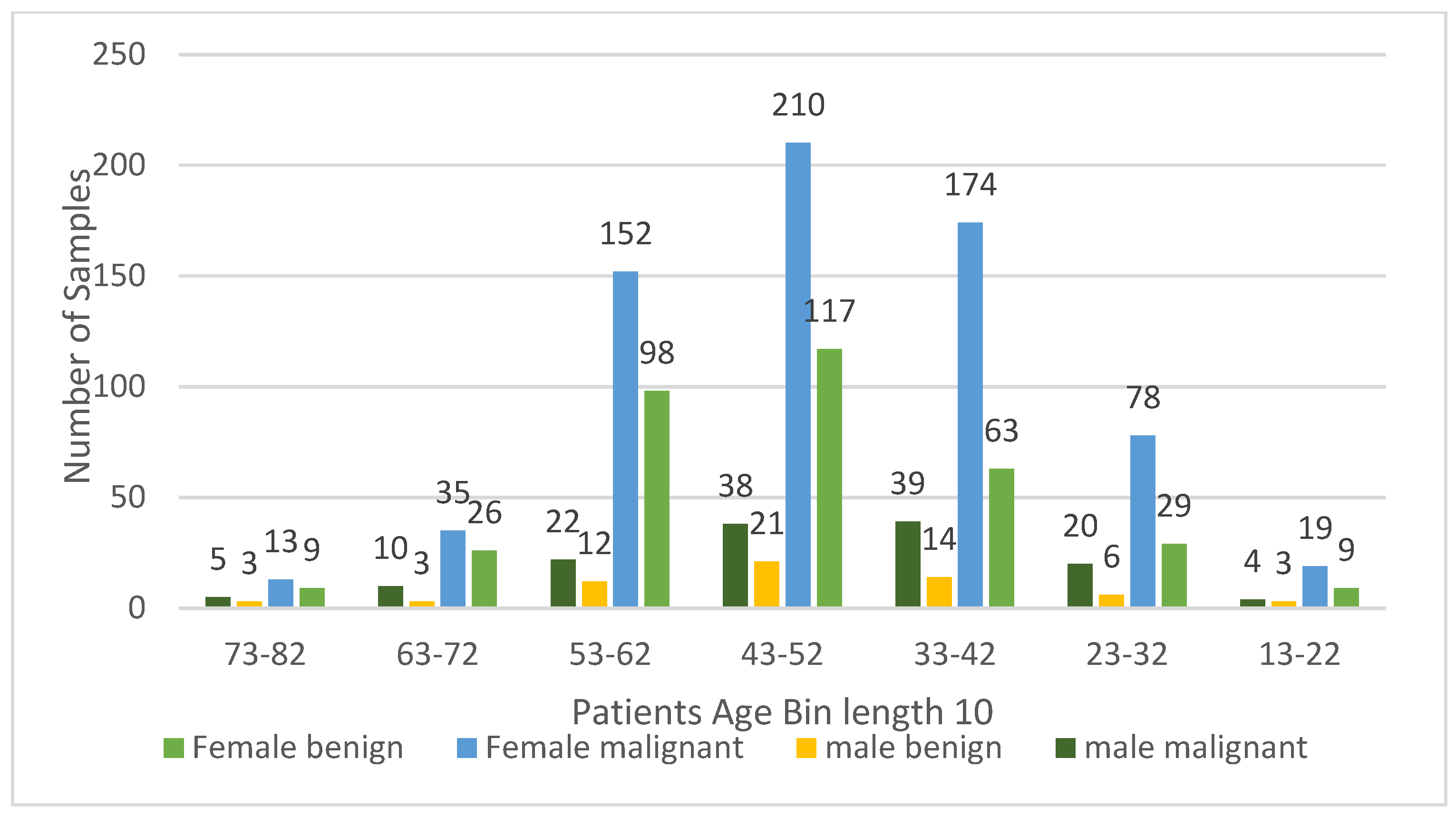

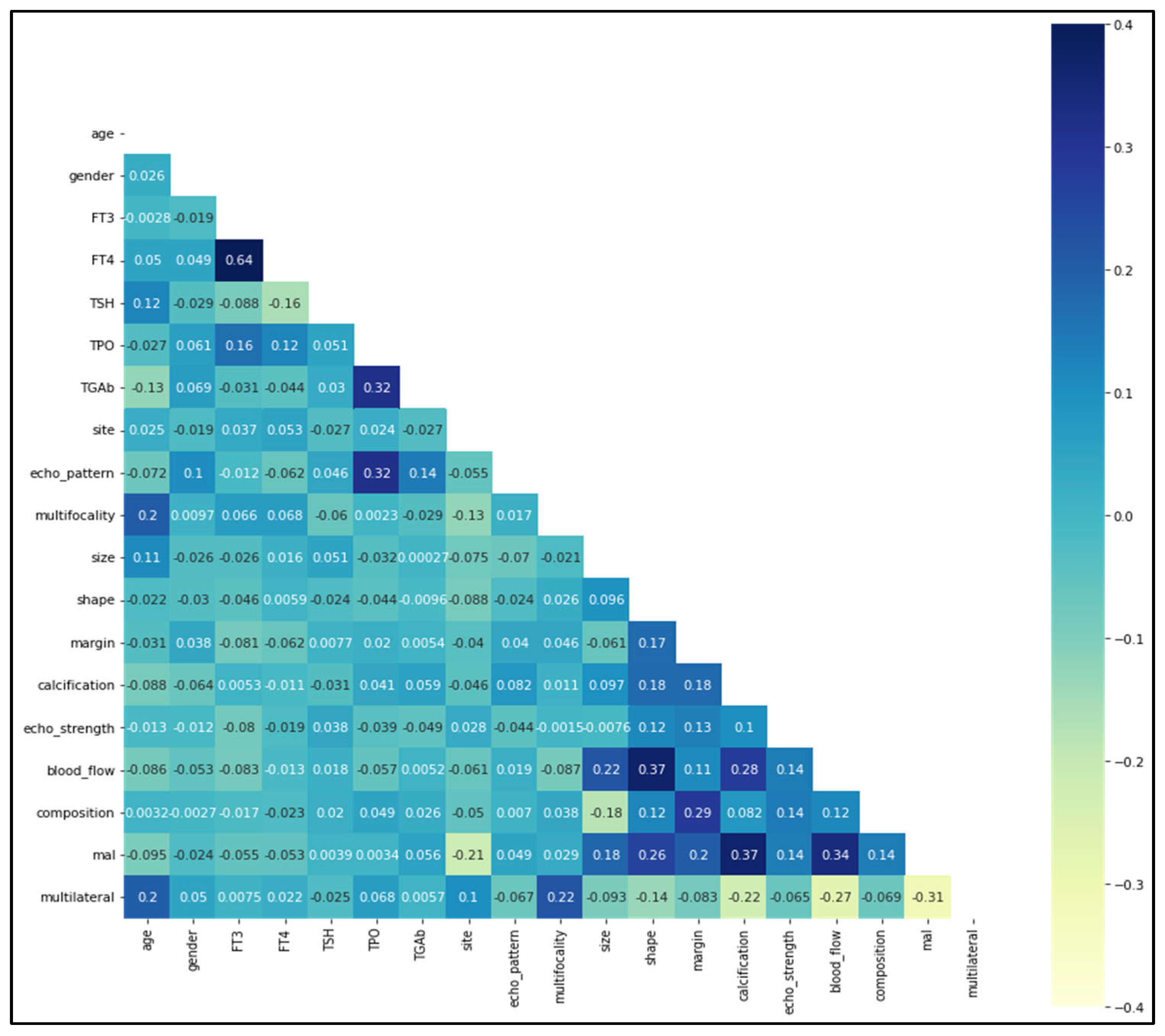

3.1. Exploratory Dataset Analysis

- Patient demographics: gender and age;

- Nodule characteristics: size, site (right, left, or isthmus), multifocality (unifocal or multifocal—i.e., whether there were multiple nodules in one location), shape (regular or irregular), calcification (absent or present), ultrasound echo strength (none, isoechoic, medium-echogenic, hyperechogenic, or hypoechogenic), margin (clear or unclear), blood flow (normal or enriched), composition (cystic, mixed, or solid), laterality (unilateral or multilateral), and malignancy (benign or malignant);

- Blood test findings: free triiodothyronine (FT3), free thyroxine (FT4), thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), thyroid peroxidase antibodies (TPO), and thyroglobulin antibodies (TgAb);

- Thyroid characteristics: echo pattern (even or uneven).

3.2. Artificial Neural Network Model

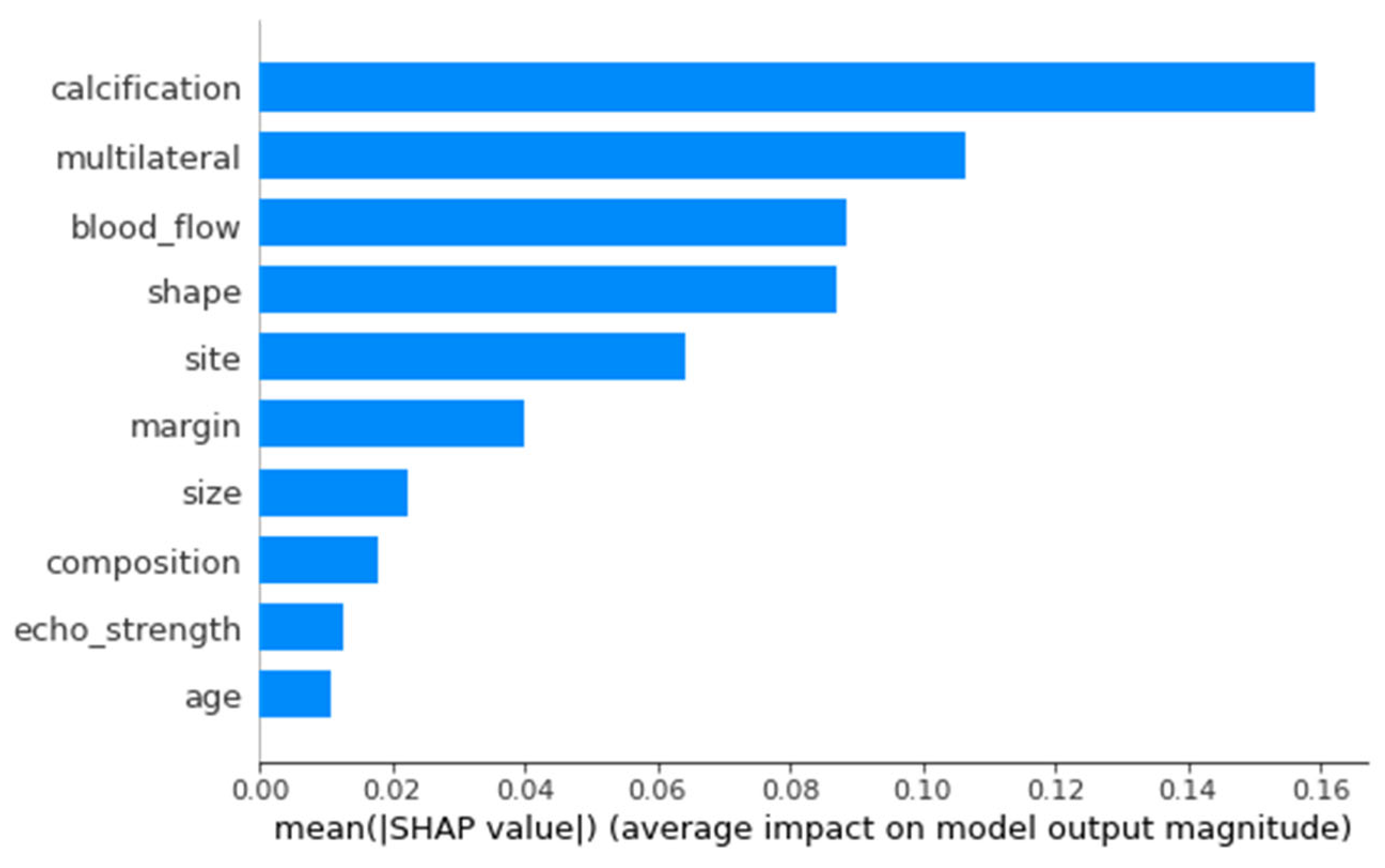

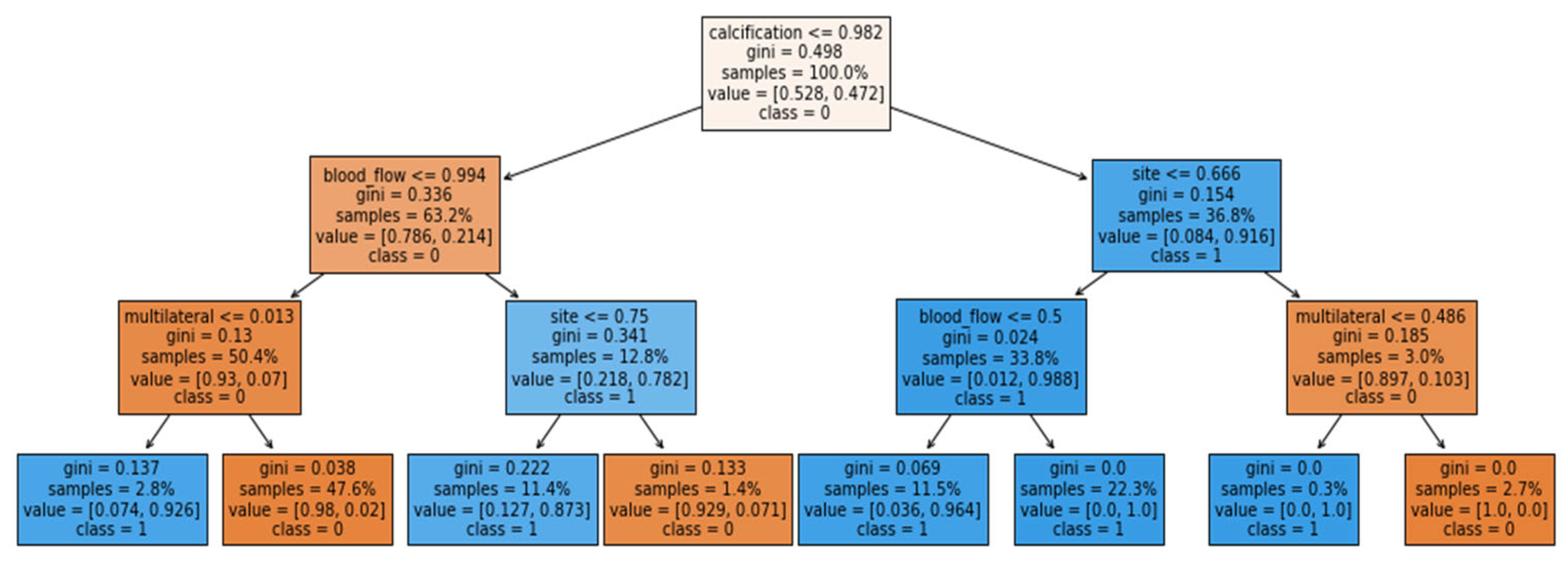

3.3. Explainability of the Proposed Model

- The name of the feature used;

- The number of samples used;

- The number of samples at the node that fall into each class;

- The Gini score: a metric that quantifies the purity of the node. A Gini score below zero means that the samples in each leaf belong to a single class.

3.4. Evaluation Measures

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Fuchs, H.E.; Jemal, A. Cancer Statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2022, 72, 7–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Cancer Society. Cancer Statistics Center. Available online: https://cancerstatisticscenter.cancer.org (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- Fagin, J.A.; Wells, S.A. Biologic and Clinical Perspectives on Thyroid Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 1054–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidbauer, B.; Menhart, K.; Hellwig, D.; Grosse, J. Differentiated Thyroid Cancer—Treatment: State of the Art. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeh, M.W.; Bauer, A.J.; Bernet, V.A.; Ferris, R.L.; Loevner, L.A.; Mandel, S.J.; Orloff, L.A.; Randolph, G.W.; Steward, D.L. American Thyroid Association Statement on Preoperative Imaging for Thyroid Cancer Surgery. Thyroid 2015, 25, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durante, C.; Grani, G.; Lamartina, L.; Filetti, S.; Mandel, S.J.; Cooper, D.S. The Diagnosis and Management of Thyroid Nodules. JAMA 2018, 319, 914–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avram, A.M.; Zukotynski, K.; Nadel, H.R.; Giovanella, L. Management of Differentiated Thyroid Cancer: The Standard of Care. J. Nucl. Med. 2022, 63, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Zhang, C.J.P.; Jiang, B.; Chen, J.; Song, J.; Liu, Z.; He, Z.; Wong, S.Y.; Fang, P.-H.; Ming, W.-K. Artificial Intelligence Versus Clinicians in Disease Diagnosis: Systematic Review. JMIR Med. Inf. 2019, 7, e10010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meske, C.; Bunde, E.; Schneider, J.; Gersch, M. Explainable Artificial Intelligence: Objectives, Stakeholders, and Future Research Opportunities. Inf. Syst. Manag. 2022, 39, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, N.M.; Wang, L.; Yang, C. Improving The Diagnosis of Thyroid Cancer by Machine Learning and Clinical Data. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.15804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, Y.; Koul, A.; Singla, R.; Ijaz, M.F. Artificial Intelligence in Disease Diagnosis: A Systematic Literature Review, Synthesizing Framework and Future Research Agenda. J. Ambient. Intell. Hum. Comput. 2022, 9, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, W.K.; Sun, J.H.; Liou, M.J.; Li, Y.R.; Chou, W.Y.; Liu, F.H.; Chen, S.T.; Peng, S.J. Using Deep Convolutional Neural Networks for Enhanced Ultrasonographic Image Diagnosis of Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naglah, A.; Khalifa, F.; Khaled, R.; Razek, A.A.K.A.; Ghazal, M.; Giridharan, G.; El-Baz, A. Novel Mri-Based Cad System for Early Detection of Thyroid Cancer Using Multi-Input CNN. Sensors 2021, 21, 3878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teknologi, J.; Ahmed, J.; Rehman, M.A. Cancer Prevention Initiative: An Intelligent Approach for Thyroid Cancer Type Diagnostics. J. Teknol. 2016, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olatunji, S.O.; Alotaibi, S.; Almutairi, E.; Alrabae, Z.; Almajid, Y.; Altabee, R.; Altassan, M.; Basheer Ahmed, M.I.; Farooqui, M.; Alhiyafi, J. Early Diagnosis of Thyroid Cancer Diseases Using Computational Intelligence Techniques: A Case Study of a Saudi Arabian Dataset. Comput. Biol. Med. 2021, 131, 104267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, F.; Zhang, J.; Li, B.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Jing, S.; Wang, G. Identification of Potential LncRNAs and MiRNAs as Diagnostic Biomarkers for Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma Based on Machine Learning. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2021, 2021, 3984463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.-N.; Liu, J.-Y.; Lin, Q.-Z.; He, Y.-S.; Luo, H.-H.; Peng, Y.-L.; Ma, B.-Y. Partially Cystic Thyroid Cancer on Conventional and Elastographic Ultrasound: A Retrospective Study and a Machine Learning—Assisted System. Ann. Transl. Med. 2020, 8, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Weng, Y.; Lund, J. Applications of Explainable Artificial Intelligence in Diagnosis and Surgery. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sappagh, S.; Alonso, J.M.; Islam, S.M.R.; Sultan, A.M.; Kwak, K.S. A Multilayer Multimodal Detection and Prediction Model Based on Explainable Artificial Intelligence for Alzheimer’s Disease. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 2660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Dai, X.; Yuan, Q.; Lu, C.; Huang, H. Towards Interpretable Clinical Diagnosis with Bayesian Network Ensembles Stacked on Entity-Aware CNNs. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Online, 5–10 July 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Magesh, P.R.; Myloth, R.D.; Tom, R.J. An Explainable Machine Learning Model for Early Detection of Parkinson’s Disease Using LIME on DaTSCAN Imagery. Comput. Biol. Med. 2020, 126, 104041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghamohammadi, M.; Madan, M.; Hong, J.K.; Watson, I. Predicting Heart Attack Through Explainable Artificial Intelligence. In International Conference on Computational Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 633–645. [Google Scholar]

- Bui, D.-K.; Nguyen, T.N.; Ngo, T.D.; Nguyen-Xuan, H. An Artificial Neural Network (ANN) Expert System Enhanced with the Electromagnetism-Based Firefly Algorithm (EFA) for Predicting the Energy Consumption in Buildings. Energy 2020, 190, 116370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toghraie, D.; Sina, N.; Jolfaei, N.A.; Hajian, M.; Afrand, M. Designing an Artificial Neural Network (ANN) to Predict the Viscosity of Silver/Ethylene Glycol Nanofluid at Different Temperatures and Volume Fraction of Nanoparticles. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2019, 534, 122142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berus, L.; Klancnik, S.; Brezocnik, M.; Ficko, M. Classifying Parkinson’s Disease Based on Acoustic Measures Using Artificial Neural Networks. Sensors 2019, 19, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Feng, J. Development and Application of Artificial Neural Network. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2018, 102, 1645–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1412.6980. [Google Scholar]

- Khalid, R.; Javaid, N. A Survey on Hyperparameters Optimization Algorithms of Forecasting Models in Smart Grid. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 61, 102275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giudici, P.; Raffinetti, E. Shapley-Lorenz EXplainable Artificial Intelligence. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 167, 114104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, G.E.A.P.A.; Prati, R.C.; Monard, M.C. A Study of the Behavior of Several Methods for Balancing Machine Learning Training Data. ACM SIGKDD Explor. Newsl. 2004, 6, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peduk, S. Predictive Importance of Ultrasonography and Anti-Thyroid Antibodies in the Management of Thyroid Nodules in Indeterminate Cytology. Eurasian J. Med. Investig. 2022, 6, 122–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Zhang, W.; Bai, W.; He, W. Relationship Between Morphologic Characteristics of Ultrasonic Calcification in Thyroid Nodules and Thyroid Carcinoma. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2020, 46, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.L.; Ha, E.J.; Han, M. Real-World Performance of Computer-Aided Diagnosis System for Thyroid Nodules Using Ultrasonography. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2019, 45, 2672–2678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazeh, H.; Samet, Y.; Hochstein, D.; Mizrahi, I.; Ariel, I.; Eid, A.; Freund, H.R. Multifocality in Well-Differentiated Thyroid Carcinomas Calls for Total Thyroidectomy. Am. J. Surg. 2011, 201, 770–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, J.-W.; Qu, Z.; Qin, A.-C.; Pan, H.; Ye, J.; Jiang, Y. Significance of Multifocality in Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2020, 46, 1820–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debnam, J.M.; Vu, T.; Sun, J.; Wei, W.; Krishnamurthy, S.; Zafereo, M.E.; Weitzman, S.P.; Garg, N.; Ahmed, S. Vascular Flow on Doppler Sonography May Not Be a Valid Characteristic to Distinguish Colloid Nodules from Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma Even When Accounting for Nodular Size. Gland Surg. 2019, 8, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramundo, V.; Lamartina, L.; Falcone, R.; Ciotti, L.; Lomonaco, C.; Biffoni, M.; Giacomelli, L.; Maranghi, M.; Durante, C.; Grani, G. Is Thyroid Nodule Location Associated with Malignancy Risk? Ultrasonography 2019, 38, 231–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasim, S.; Baranski, T.J.; Teefey, S.A.; Middleton, W.D. Investigating the Effect of Thyroid Nodule Location on the Risk of Thyroid Cancer. Thyroid 2020, 30, 401–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.; Xi, B.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, L.; Sui, X.; Tian, G.; Yang, J. A Machine Learning-Based Diagnosis of Thyroid Cancer Using Thyroid Nodules Ultrasound Images. Curr. Bioinform. 2020, 15, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Feature Set | Techniques | Accuracy | Sensitivity | Specificity | Precision | F1 Score | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full Features | Original Dataset | 0.82 | 0.82 | 0.70 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 0.86 |

| SMOTEENN Combined sampling | 0.99 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | |

| SOMTE Oversampling | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.86 | 0.81 | 0.88 | 0.89 | |

| Selected features | Original Dataset | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.65 | 0.82 | 0.87 |

| SMOTEENN Combined sampling | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.98 | |

| SOMTE Oversampling | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.88 | 0.84 | 0.82 | 0.88 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aljameel, S.S. A Proactive Explainable Artificial Neural Network Model for the Early Diagnosis of Thyroid Cancer. Computation 2022, 10, 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/computation10100183

Aljameel SS. A Proactive Explainable Artificial Neural Network Model for the Early Diagnosis of Thyroid Cancer. Computation. 2022; 10(10):183. https://doi.org/10.3390/computation10100183

Chicago/Turabian StyleAljameel, Sumayh S. 2022. "A Proactive Explainable Artificial Neural Network Model for the Early Diagnosis of Thyroid Cancer" Computation 10, no. 10: 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/computation10100183

APA StyleAljameel, S. S. (2022). A Proactive Explainable Artificial Neural Network Model for the Early Diagnosis of Thyroid Cancer. Computation, 10(10), 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/computation10100183