Holy Mothers in the Vietnamese Diaspora: Refugees, Community, and Nation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background on Catholicism and Caodaism in Vietnam

2.1. Catholicism

2.2. Caodaism

3. The Religious Significance of Holy Mothers

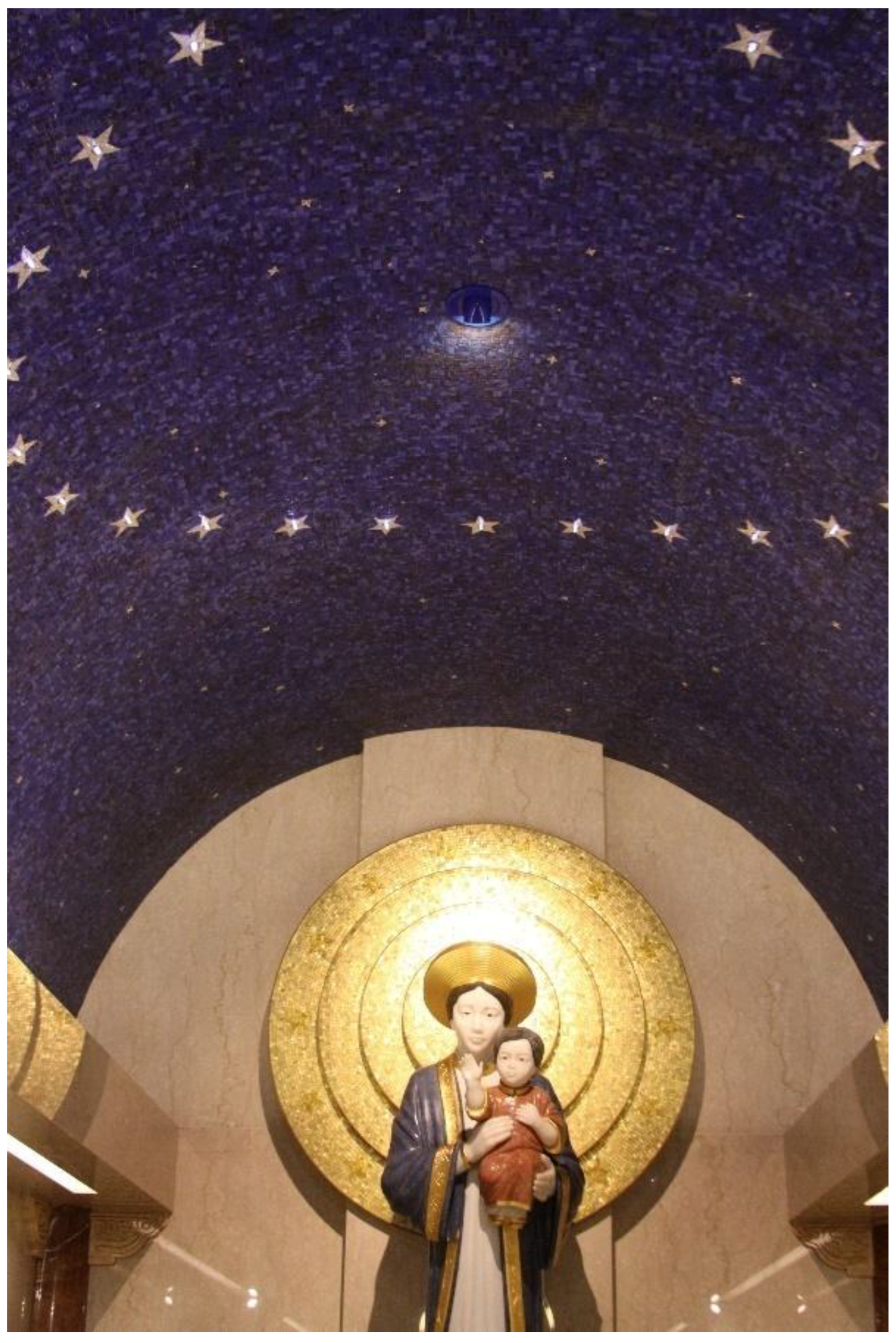

3.1. Our Lady of Lavang

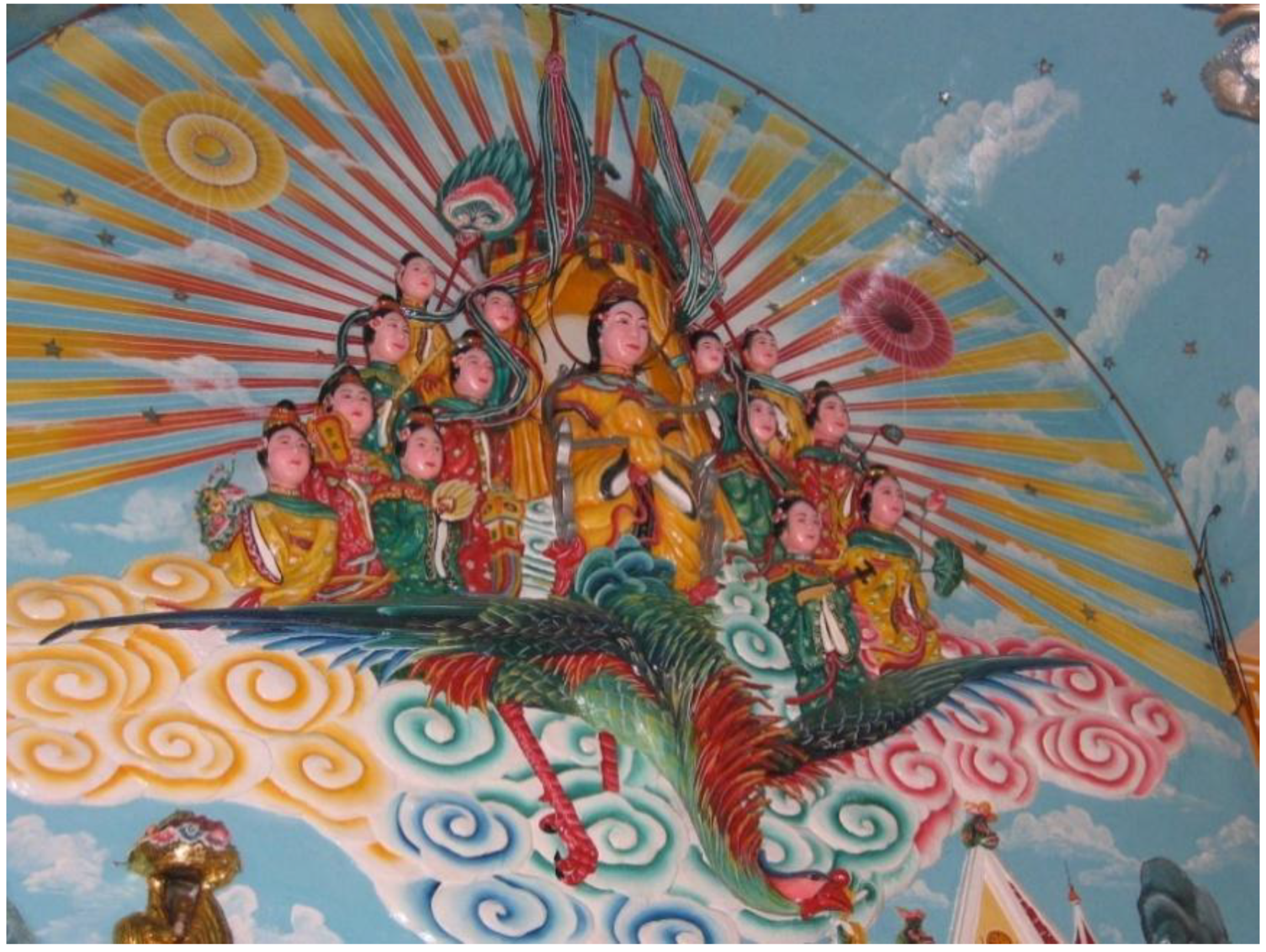

3.2. Caodai Mother Goddess

4. Vietnamese Holy Mothers and Community Centralization in the Diaspora

4.1. Context

4.2. Our Lady of Lavang

4.3. The Caodai Mother Goddess

5. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bankston, Carl L., III, and Min Zhou. 1996. The Ethnic Church, Ethnic Identification, and the Social Adjustment of Vietnamese Adolescents. Review of Religious Research 38: 18–37. [Google Scholar]

- Baumann, Martin. 2000. Diaspora: Genealogies of Semantics and Transcultural Comparison. Numen 47: 313–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, Van T. 1986. Cá Gốc Của Phước Thiện. Tay Ninh: Tay Ninh Holy See. [Google Scholar]

- Burwell, Ronald J., Peter Hill, and John F. Wicklin. 1986. Religion and Refugee Resettlement in the United States: A Research Note. Review of Religious Research 27: 356–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camda, Edward R., and Thitiya Phaobtong. 1992. Buddhism as a Support System for Southeast Asian Refugees. Social Work 37: 61–67. [Google Scholar]

- Castañeda-Liles, María Del. 2018. Our Lady of Everyday Life: La Virgen de Guadalupe and the Catholic Imagination of Mexican Women in America. New York: Oxford University. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, Lan. 2008. Catholicism vs. Communism, Continued: The Catholic Church in Vietnam. Journal of Vietnamese Studies 3: 151–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, J. B. An. 2008. Hanoi’s Catholics Continue Protests Defying Government’s Ultimatum. AsiaNews.it. Available online: www.asianews.it/index.php?l=en&art=11365&size=A (accessed on 2 May 2013).

- Dorais, Louis-Jacques. 2001. Defining the Overseas Vietnamese. Diaspora 10: 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorais, Louis-Jacques. 2005. From Refugees to Transmigrants: The Vietnamese in Canada. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dunning, Bruce B. 1982. A Systematic Study of the Social, Psychological and Economic Adaptation of Vietnamese Refugees Representing Five Entry Cohorts, 1975–1979. Washington: Bureau of Social Science Research Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Dunning, Bruce. 1989. Vietnamese in America: The adaptation of the 1975–1979 arrivals. In Refugees as Immigrants: Cambodians, Laotians, and Vietnamese in America. Edited by David W. Haines. Totowa: Rowman and Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Dutton, George. 2016. A Vietnamese Moses: Philiphê Bình and the Geographies of Early Modern Catholicism. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Duricy, Michael. 2008. Black Madonnas: Our Lady of Czestochowa. Dayton: Marian. [Google Scholar]

- Endres, Kirsten W. 2011. Performing the Divine: Mediums, Markets and Modernity in Urban Vietnam. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. [Google Scholar]

- Espiritu, Yen Le. 2014. Body Counts: The Vietnam War and Militarized Refugees. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Espiritu, Yen Le. 2002. ‘Viet Nam, Nuoc Toi’ (Vietnam, My Country): Vietnamese Americans and Transnationalism. In The Changing Face of Home. Edited by Peggy Levitt and Mary C. Waters. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez, Eleazar. 2003. America from the Hearts of a Diasporized People. In Revealing the Sacred in Asia and Pacific America. Edited by Jane N. Iwamura and Paul Spickard. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Fjeldstad, Karen. 1995. Tu Phu Cong Dong: Vietnamese Women and Spirit Possession in the San Francisco Bay Area. Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Anthropology, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, HI, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Fjelstad, Karen, and Nguyen Thi Hien. 2006. Introduction. In Possessed by the Spirits: Mediumship in Contemporary Vietnamese Communities. Edited by Karen Fjelstad and Hien Thi Nguyen. Ithaca: Cornell University, pp. 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Fjelstad, Karen, and Nguyen Thi Hien. 2011. Spirits without Borders: Vietnamese Spirit Mediums in a Transnational Age. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, David, ed. 1997. Lived Religion in America: Toward a History of Practice. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, Peter. 2009. Bắc Di Cư: Catholic Refugees from the North of Vietnam, and Their Role in the Southern Republic, 1954–1959. Journal of Vietnamese Studies 4: 173–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, Linh. 2006. Creating New Spiritual Homes: Vietnamese Refugees Negotiating American and Catholic Identities. New York: Fordham University. [Google Scholar]

- Home Office. 2018. Vietnam: Ethnic and Religious Groups. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/695864/Vietnam_-_Ethnic_and_Religious_groups_-_CPIN_v2.0_ex.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2018).

- Horsfall, Sara. 2000. The Experience of Marian Apparitions and the Mary Cult. Social Science Journal 37: 375–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoskins, Janet A. 2015. The Divine Eye and the Diaspora: Vietnamese Syncretism Becomes Transpacific Caodaism. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hoskins, Janet. 2006. Caodai Exile and Redemption: A New Vietnamese Religion’s Struggle for Identity. In Religion and Social Justice for Immigrants. Edited by Pierrette Hondagneu-Sotelo. Rutgers: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hoskins, Janet. 2012a. A Posthumous Return from Exile: The Legacy of an Anticolonial Religious Leader in Today’s Vietnam. Southeast Asian Studies 1: 213–46. [Google Scholar]

- Hoskins, Janet. 2012b. Can a hierarchical religion survive without its center? Caodaism, colonialism, and exile. In Hierarchy: Persistence and Transformation in Social Formations. Oxford: Berghahn Books. [Google Scholar]

- Huynh, Nathalie, and Chau Nguyen. 2009. Memory Is Another Country: Women of the Vietnamese Diaspora. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. [Google Scholar]

- Huynh, Thuan. 2000. Center for Vietnamese Buddhism: Recreating home. In Religion and the New Immigrants: Continuities and Adaptations in Immigrant Congregations. Edited by Helen R. Ebaugh and Janet S. Chafetz. New York: Altamira Press. [Google Scholar]

- Keith, Charles. 2006. Catholic Vietnam: A Church from Empire to Nation. Berkeley: University of California. [Google Scholar]

- Kokot, Waltraud, Khachig Tololyan, and Carolin Alfonso, eds. 2004. Introduction. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, Heonik. 2008. Ghosts of War in Vietnam. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, Robert E., Mark W. Fraser, and Peter J. Pecora. 1988. Religiosity among Indochinese Refugees in Utah. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 27: 272–83. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 27: 272–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Nam. 2001. The range of religious healing options in the Boston Vietnamese community. In Religious Healing in Boston: First Findings. Edited by Susan Sered and Linda L. Barnes. Cambridge: Harvard Divinity School, Center for the Study of World Religions. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, Viet Thanh. 2012. Refugee Memories and Asian American Critique. Positions: East Asia Cultures Critique 20: 911–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Y. Thien. 2018. (Re)making the South Vietnamese Past in America. Journal of Asian American Studies 21: 65–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Vo, Thu-Huong. 2005. Forking Paths: How Shall We Mourn the Dead? Amerasia Journal 31: 157–75. [Google Scholar]

- Ninh, Thien-Huong. 2017. Race, Gender, and Religion in the Vietnamese Diaspora: The New Chosen People. Cham: Palgrave. [Google Scholar]

- Noseworthy, William. 2015. The Mother Goddess of Champa: Po Ina Nagar. SUVANNABHUMI: Multi-Disciplinary Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 7: 107–38. [Google Scholar]

- Orsi, Robert. 2010. The Madonna of 115th Street: Faith and Community in Italian Harlem, 1880–1950. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Peché, Linda Ho. 2012. I’d pay homage, not go ‘All Bling’: Race, religion and Vietnamese American youth. In Sustaining Faith Traditions: Race, Ethnicity, and Religion among the Latino and Asian American Second Generation. Edited by Carolyn Chen and Russell Jeung. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Phạm , Công Tắc. 1947. Trích Thuyết Đạo (Cathecism or Religious Doctrines). Available online: https://www.daotam.info/booksv/dpmdtkm.htm (accessed on 17 July 2018).

- Phan, Peter C. 1991. Aspects of Vietnamese Culture and Roman Catholicism: Background Information for Educators of Vietnamese Seminarians. Seminaries in Dialogue 23: 2–8. [Google Scholar]

- Phan, Peter C. 2003. Christianity with an Asian Face: Asian American Theology in the Making. Maryknoll: Orbis Books. [Google Scholar]

- Phan, Peter C. 2005. Mary in Vietnamese Piety and Theology: A Contemporary Perspective. Ephemerides Mariologicae 51: 457–72. [Google Scholar]

- Phan, Peter C. 2006. Christianity in Indochina. In World Christianities, c. 1815–c. 1914. Edited by Sheridan Gilley and Brian Stanley. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pham, Quynh Phuong, and Chris Eipper. 2009. Mothering and Fathering the Vietnamese: Religion, Gender, and National Identity. Journal of Vietnamese Studies 4: 49–83. [Google Scholar]

- Province de Tayninh: Stat des Personnes Frequentantla Pagodede Caodai Pendantle Moisde Juin. 1927. Box: Caodaism, Archives Nationalesd’Outre-mer (French National Colonial Archives).

- Rutledge, Paul. 1985. The Role of Religion in Ethnic Self-Identity. Lanham: University Press of America. [Google Scholar]

- Said, Edward. 1984. Reflections of Exile. Granta 13: 159–72. [Google Scholar]

- Salemink, Oscar. 2015. Spirit worship and possession in Vietnam and beyond. In Routledge Handbook of Religions in Asia. Edited by Bryan S. Turner and Oscar Salemink. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Smart, Ninian. 1987. The Importance of Diasporas. In Gilgul: Essays on Transformation, Revolution, and Permanence in the History of Religions. Edited by Shaul Shaked, David Shulman and Gedaliahu G. Stroumsa. Leiden: Brill, pp. 288–97. [Google Scholar]

- Sökefeld, Martin. 2004. Religion or Culture? Concepts of Identity in the Alevi Diaspora. In Diaspora, Identity and Religion—New Directions in Theory and Research. Edited by Carolin Alfonso, Waltraud Kokot and Khachig Tölölyan. New York: Routledge, pp. 133–55. [Google Scholar]

- Tai, Hue-Tam Ho. 2001. The Country of Memory: Remaking the Past in Late Socialist Vietnam. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Philip. 2001. Fragments of the Present: Searching for Modernity in Vietnam’s South. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Philip. 2004. Goddess on the Rise: Pilgrimage and Popular Religion in Vietnam. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tölölyan, Khachig. 1996. Rethinking Diaspora(s): Stateless Power in the Transnational Moment. Diaspora: A Journal of Transnational Studies 5: 3–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, Quang C. 2009. Trung Tâm Thánh Mẫu Toàn Quốc La Vang [The National Marian Center of Lavang]. Tổng Giáo Phận Huế (The Archdiocese of Hue). Available online: http://tonggiaophanhue.net/home/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=38:phn-1-s-tich-c-m-la-vang&catid=14:duc-me-lavang&Itemid=99 (accessed on 24 June 2013).

- Truitt, Allison. 2017. Quán Thế Âm of the Transpacific. Journal of Vietnamese Studies 12: 83–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tweed, Thomas. 1997. Our Lady of the Exile: Diasporic Religion at a Cuban Shrine in Miami. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- UCAN (The Union of Catholic Asian News). 2011. Government Works on Church Property. Ucanews.com. Available online: http://www.ucanews.com/news/government-to-use-church-property/35694 (accessed on 2 May 2018).

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2016. American Community Survey: Vietnamese. Available online: https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?src=bkmk (accessed on 28 June 2018).

- Vertovec, Steven. 1999. Three Meanings of ‘Diaspora,’ Exemplified among South Asian Religions. Diaspora 7: 277–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vertovec, Steven. 2000. Religion and Diaspora. Paper presented at New Landscapes of Religion in the West, School of Geography and the Environment, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK, September 27–29. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | I use “worship,” “venerate” and “honor” interchangeably in this paper. I am aware that the meanings of these words vary across different religious traditions. For example, Vietnamese Catholics worship only God and venerate or honor other religious figures, including the Virgin Mary. On the other hand, Vietnamese Caodaists worship and venerate both the (male) Supreme Being and the Mother Goddess as complementary spiritual entities. |

| 2 | There are 54 officially-recognized ethnic groups in Vietnam. |

| 3 | Caodaism has several sects. This paper focuses on the largest one, which is the Tay Ninh Caodai group. |

| 4 | Lavang is approximately 60 km north of Hue (the former capital of Vietnam) in central Vietnam. |

| 5 | On 13 June 1992, Vietnamese American Caodaists officially declared the establishment of the “Religious Province of California” (Châu Đạo California) at the Vietnamese Convention Center in Westminster City. Under the leadership of a former dignitary who was ordained by the pre-1975 Caodai Holy See, Thuong Mang Thanh, the religious province functioned as the umbrella organization and representative of all other denominational Tay Ninh Caodai religious centers in California. At the time of its establishment, member temples included one Caodai God temple in Westminster, another one in Sacramento, and a Mother Goddess shrine and Caodai God temple in San Jose. It was the highest and largest Caodai organization outside of Vietnam. The Religious Province of California quickly became the public face of the Caodai community, representing it at events such as neighborhood parades and city council meetings. It mediated connections and exchanges among Caodaists dispersed throughout the world, as exemplified through its regular publication of the Qui Nguyen magazine, maintenance of a popular website, and the distribution of CDs on community activities. The religious province also organized and hosted a number of important national and international events, including meetings among overseas Caodai dignitaries and summer youth retreats. |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ninh, T.-H. Holy Mothers in the Vietnamese Diaspora: Refugees, Community, and Nation. Religions 2018, 9, 233. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9080233

Ninh T-H. Holy Mothers in the Vietnamese Diaspora: Refugees, Community, and Nation. Religions. 2018; 9(8):233. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9080233

Chicago/Turabian StyleNinh, Thien-Huong. 2018. "Holy Mothers in the Vietnamese Diaspora: Refugees, Community, and Nation" Religions 9, no. 8: 233. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9080233

APA StyleNinh, T.-H. (2018). Holy Mothers in the Vietnamese Diaspora: Refugees, Community, and Nation. Religions, 9(8), 233. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9080233