“Vibrating between Hope and Fear”: The European War and American Presbyterian Foreign Missions

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The Great War: A Turning Point for Philanthropy and Humanitarianism?

3. Presbyterians and Foreign Missions

4. Apportionments and the Every Member Canvass: Balancing Financial Goals with Donor Empowerment

5. Neutral “in Speech and Writing”, Though Perhaps Not in Deed

6. Warlike in Speech and Writing

7. American Entry into the War

Forwarding the letter to several of his colleagues, Brown stressed the point even further, identifying the continuing service of missionaries as “absolutely essential to the cause of humanity and righteousness and liberty”.75 Foreign missionaries ought to be exempted from selective service, Brown argued, because they had already volunteered to serve God and country.Missionary work … is of indispensable value as a humanitarian as well as a Christian enterprise. … Indeed missionary work is one of the most powerful, if not the most powerful influence in creating and strengthening the bonds of sympathy and good feeling between the United States and other nations. … It is not a question whether foreign missionaries are to serve their country; of course they are to do this. The question is whether they are not doing so to better advantage in their missionary work than if they were to enter the ranks in the army or navy.74

8. The American Red Cross: Non-Sectarian, State-Supported Philanthropy as a Better Way?

9. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- 1916. A Worthy Gain. Missionary Herald 112: 23–24.

- Alexander, Maitland. 1915. Sacrificial Emergency Call of the Presbyterian Church. Assembly Herald 21: 14. [Google Scholar]

- American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions Archives. 1810–1961. Cambridge: Houghton Library, Harvard University.

- Barnett, Michael N. 2011. Empire of Humanity: A History of Humanitarianism. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bays, Daniel H., and Grand Wacker, eds. 2003. The Foreign Missionary Enterprise at Home: Explorations in North American Cultural History. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press. [Google Scholar]

- Beaver, R. Pierce. 1968. All Loves Excelling: American Protestant Women in World Mission. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [Google Scholar]

- Bergland, Betty Ann. 2010. Settler Colonists, ‘Christian Citizenship,’ and the Women’s Missionary Federation at the Bethany Indian Mission in Wittenberg, Wisconsin, 1884–1934. In Competing Kingdoms: Women, Mission, Nation, and the American Protestant Empire, 1812–1960. Edited by Barbara Reeves-Ellington, Kathryn Kish Sklar and Connie Anne Shemo. Durham: Duke University Press, pp. 167–94. [Google Scholar]

- Cabanes, Bruno. 2014. The Great War and the Origins of Humanitarianism, 1918–1924. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Capozzola, Christopher. 2008. Uncle Sam Wants You: World War I and the Making of the Modern American Citizen. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 1914. Christmas is a World Opportunity. Assembly Herald 20: 642.

- Coyle, Robert Francis. 1914. Forward with Christ. Assembly Herald 20: 4–5. [Google Scholar]

- Cutlip, Scott M. 1965. Fund Raising in the United States: Its Role in America’s Philanthropy. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eastman, E. Fred. 1917. The Church and the Red Cross. Assembly Herald 23: 544–47. [Google Scholar]

- 1915. Echoes from the War Zone. Assembly Herald 21: 498–501.

- Farwell, Byron. 1986. The Great War in Africa, 1914–1918. New York: Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Fahs, Charles H. 1929. Trends in Protestant Giving: A Study of Church Finance in the United States. New York: Institute of Social and Religious Research. [Google Scholar]

- Foreign Missions Conference of North America Records. 1887–1951. NCC RG 27. Philadelphia: Presbyterian Historical Society.

- Fronc, Jennifer. 2009. New York Undercover: Private Surveillance in the Progressive Era. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gerwarth, Robert, and Erez Manela. 2014. Introduction. In Empires at War 1911–1923. Edited by Robert Gerwarth and Erez Manela. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, Beverly. 1998. Bazaars and Fair Ladies: The History of the American Fundraising Fair. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hasinoff, Erin L. 2011. Faith in Objects: American Missionary Expositions in the Early Twentieth Century. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Hitchcock, William I. 2014. World War I and the Humanitarian Impulse. The Tocqueville Review/La revue Tocqueville 35: 145–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudnut-Beumler, James. 2007. In Pursuit of the Almighty’s Dollar: A History of Money and American Protestantism. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchison, William R. 1987. Errand to the World: American Protestant Thought and Foreign Missions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Iriye, Akira. 2002. Global Community: The Role of International Organizations in the Making of the Contemporary World. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Irwin, Julia. 2013. Making the World Safe: The American Red Cross and a Nation’s Humanitarian Awakening. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kazin, Michael. 2006. A Godly Hero: The Life of William Jennings Bryan. New York: Knopf. [Google Scholar]

- Leach, William H. 1958. Handbook of Church Management. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Little, John Branden. 2009. Band of Crusaders: American Humanitarians, the Great War, and the Remaking of the World. Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Manela, Erez. 2007. The Wilsonian Moment: Self-Determination and the International Origins of Anticolonial Nationalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, Kathleen D. 2003. American Creed: Philanthropy and the Rise of Civil Society, 1700–1865. Chicago: University of Chicago. [Google Scholar]

- 1913. Methods that Win. Men and Missions 5: 8–12.

- Minutes of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America. 1911. New Series; Philadelphia: Office of the General Assembly, vol. 11.

- Minutes of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America. 1912. New Series; Philadelphia: Office of the General Assembly, vol. 12.

- Mislin, David. 2015. One Nation, Three Faiths: World War I and the Shaping of ‘Protestant-Catholic-Jewish’ America. Church History 84: 828–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgenthau, Henry, and French Strother. 1922. All in a Life-Time. Garden City: Doubleday, Page and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Moyn, Samuel. 2010. The Last Utopia: Human Rights in History. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moyn, Samuel. 2015. Christian Human Rights. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pierce, Lyman L. 1938. Philanthropy—A Major Big Business. The Public Opinion Quarterly 2: 140–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, Andrew. 2004. Religion versus Empire? British Protestant Missionaries and Overseas Expansion, 1700–1914. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Reeves-Ellington, Barbara, Kathryn Kish Sklar, and Connie Anne Shemo, eds. 2010. Competing Kingdoms: Women, Mission, Nation, and the American Protestant Empire, 1812–1960. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Robert, Dana L. 1997. American Women in Mission: A Social History of Their Thought and Practice. Macon: Mercer University Press. [Google Scholar]

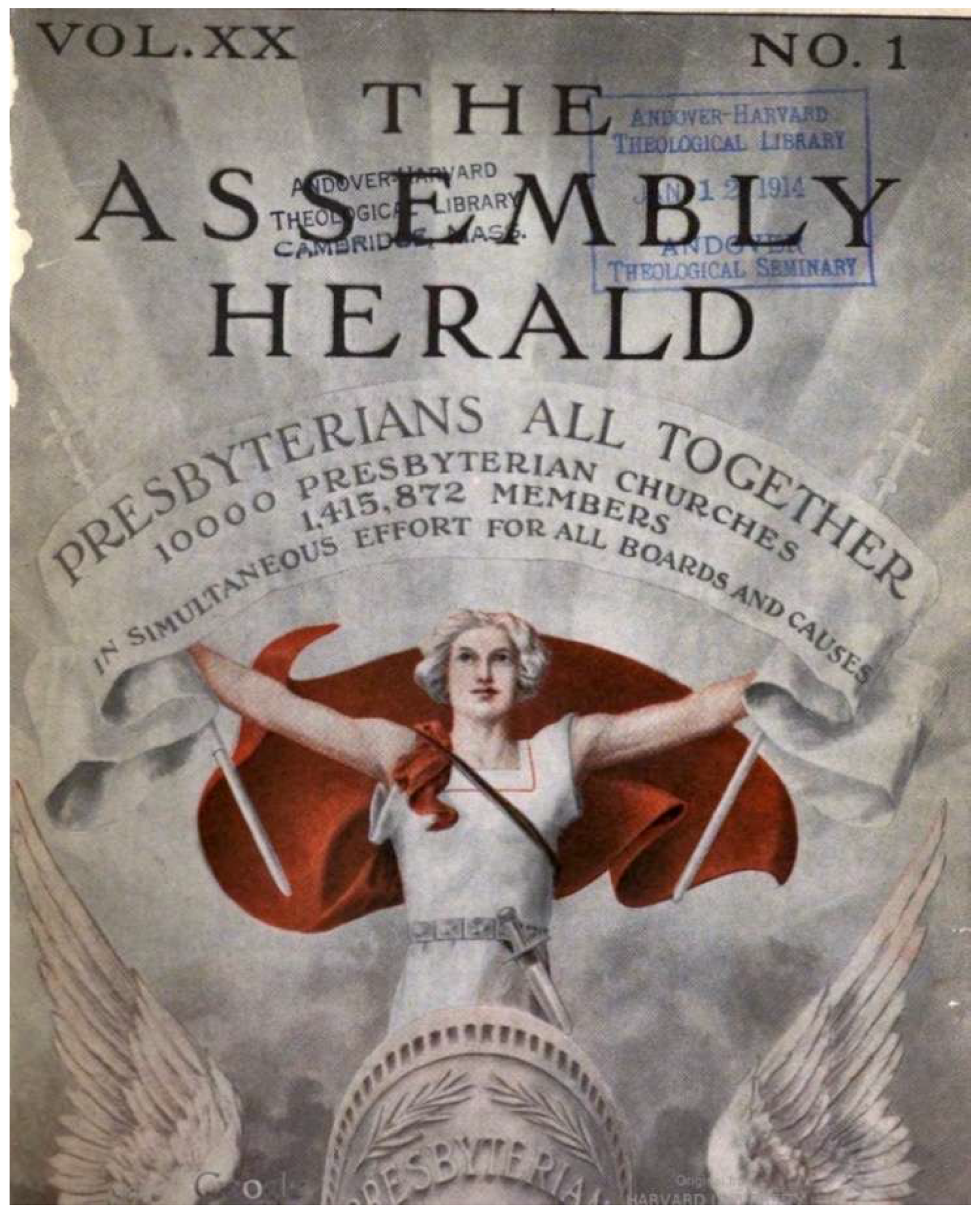

- Robert, Dana L., ed. 2008. Converting Colonialism: Visions and Realities in Mission History, 1706–1914. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, Richard. 2013. Saving the City: The Great Financial Crisis of 1914. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shenk, Wilbert R., ed. 2004. North American Foreign Missions, 1810–1914: Theology, Theory, and Policy. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [Google Scholar]

- Showalter, Nathan D. 1998. The End of a Crusade: The Student Volunteer Movement for Foreign Missions and the Great War. Lanham: Scarecrow Press. [Google Scholar]

- Speer, Robert E. 1914. The Home Base. Assembly Herald 20: 302–3. [Google Scholar]

- 1915. Syria. Assembly Herald 21: 500–1.

- 1915. The Effect of the War upon Mission Work in China. Assembly Herald 21: 16–17.

- 1915. The European War as Seen on the Mission Field. Assembly Herald 21: 17–18.

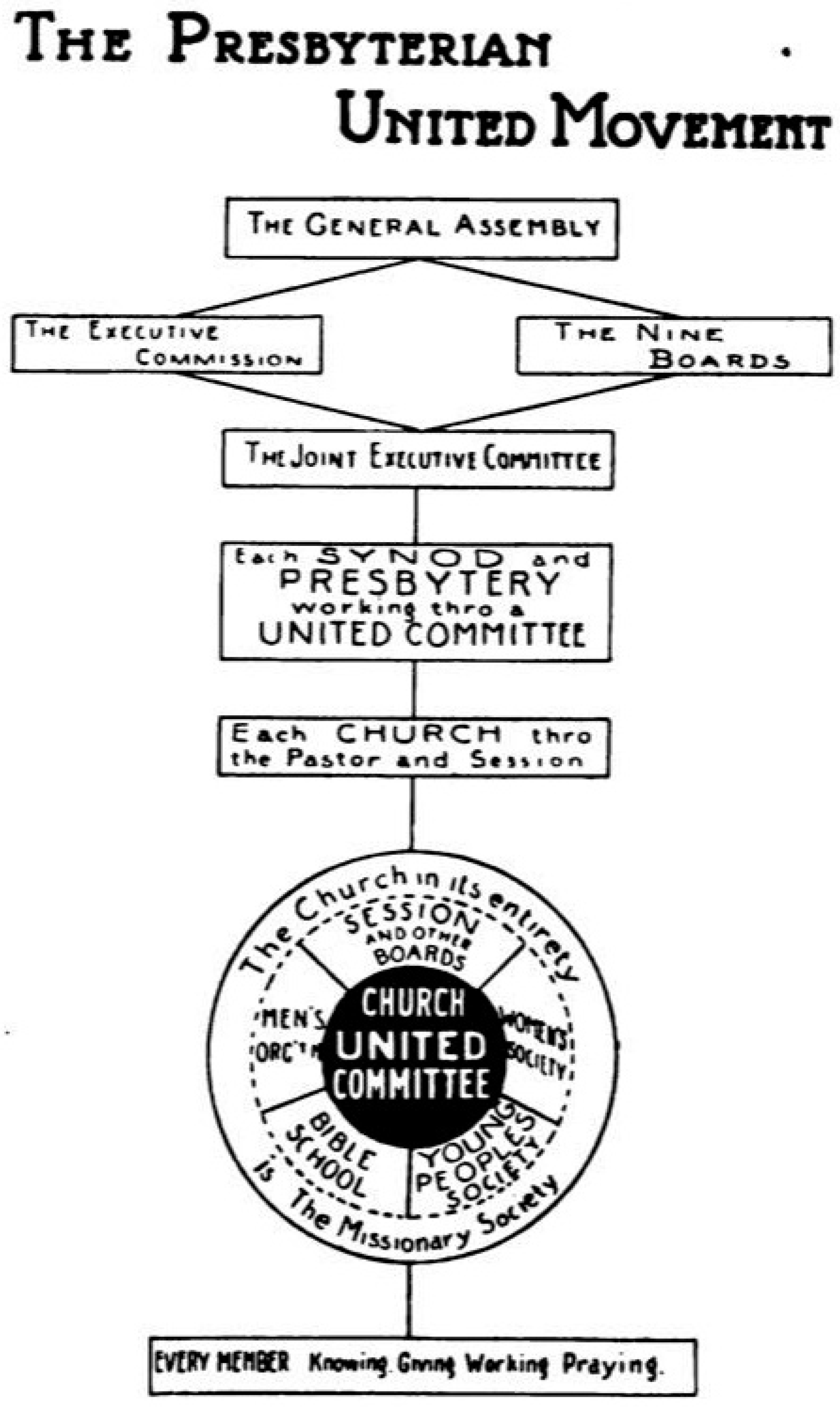

- 1914. The Presbyterian United Movement. Assembly Herald 20: 183–85.

- 1917. The Presbyterian United Movement. Assembly Herald 23: 571.

- 1914. The Syrian Situation. Assembly Herald 20: 643–44.

- 1913. The Why and How of the Canvass. Men and Missions 5: 12–15.

- Tyrrell, Ian R. 2010. Reforming the World: The Creation of America’s Moral Empire. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- United Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A. Commission on Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records. 1892–1965. RG 81. Philadelphia: Presbyterian Historical Society.

- Walther, Karine. 2016. For God and Country: James Barton, the Ottoman Empire and Missionary Diplomacy During World War I. First World War Studies 7: 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 1915. War and Missions. Assembly Herald 21: 548–52.

- 1915. War News from Workers at the Front. Assembly Herald 21: 111–15.

- 1915. War Relief Work. Assembly Herald 21: 691–92.

- Watenpaugh, Keith David. 2010. The League of Nations’ Rescue of Armenian Genocide Survivors and the Making of Modern Humanitarianism, 1920–1927. The American Historical Review 115: 1315–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watenpaugh, Keith David. 2015. Bread from Stones: The Middle East and the Making of Modern Humanitarianism. Oakland: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, Herman C. 1932. The Every Member Canvass: People or Pocket-Books. New York: Fleming H. Revell. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, Warren H. 1917. The Gospel Ministry and the War. Assembly Herald 23: 538–41. [Google Scholar]

- Zunz, Olivier. 2012. Philanthropy in America: A History. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Which is not to say missionaries or missionary officials used a different term even when discussing “critical” situations in Africa and the “most serious situation” in China. “Presbyterian Missions and the European War”, Bulletin No. 7, September 1914, United Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A. Commission on Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records, RG 81, box 6, folder 23, Presbyterian Historical Society, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (hereafter Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records). |

| 2 | Julia Irwin (2013, p. 14), for instance, notes that Evangelical Christianity had been a “mobilizing impulse for … humanitarian activities, at home and abroad” in the nineteenth century and lumps missions together with “charitable assistance” and “social reform” as “humanitarian activities”. She makes this point while claiming that “American humanitarians increasingly defined their work in non-sectarian and social scientific terms”. What is left unsaid is that sectarian organizations themselves also promoted non-sectarianism and social scientific approaches. |

| 3 | In numerous instances where the global banking structure temporarily halted, Standard Oil provided American transnational nonprofits with a source of money. It was one of the few American corporations whose reach extended almost as far as foreign missions and whose wealth vastly exceeded any charitable society. Arthur Brown to “friends”, 23 September 1914, box 6, folder 23, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records. |

| 4 | Arthur Brown, “Bulletin No. 1”, 24 August 1914, box 6, folder 23, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records. |

| 5 | Cornelius Patton to E. L. Smith, 17 August 1914, American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions Archives 1810–1961 (ABC 4.1, vol. 20) Houghton Library, Harvard University (hereafter ABCFM Archives). |

| 6 | C. A. Dana to Russell Carter, 8 August 1914, box 6, folder 22, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records. |

| 7 | James Barton to Arthur Brown, 21 August 1914, box 6, folder 22, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records. |

| 8 | A. Woodruff Halsey to D. Stuart Dodge, 27 August 1914, box 6, folder 22, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records. |

| 9 | Circular from James Barton, 28 August 1914, ABC 9.5.1, box 8, folder 12, and Cornelius Patton to Brewer Eddy, 27 August 1914, ABC 4.1, vol. 20, ABCFM Archives; Correspondence between Presbyterian Board of Foreign Missions and the US State Department, August–September 1914, box 6, folder 22, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records. |

| 10 | A. Woodruff Halsey to Cleveland Dodge, 2 September 1914, box 6, folder 22, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records. |

| 11 | “U.S. Cruisers to Remain in Europe”, New York Tribune, 24 September 1914; “Syrian Ports Fear Attack by French”, New York Tribune, 19 October 1914; “U.S. Ready to Aid Americans in East”, New York Tribune, 31 October 1914; Katherine Jessup to Ralph E. Prime, 20 December 1914, box 6, folder 22, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records; Russell Carter to the BFM secretaries, quoting a letter from Charles Dana, 4 March 1915, box 6, folder 24, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records. |

| 12 | By the following summer, the American Board was using its ability to get funds to mission stations throughout Turkey as a fundraising method. James Barton, “Bulletin on the Turkish Situation”, 3 July 1915, box 6, folder 24, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records. |

| 13 | John Branden Little and Akira Iriye have drawn opposite conclusions about the history of World War I nonprofit work, but each emphasizes rupture rather than continuity and evolution. Little notes that “few relief organizations founded in World War I remained active internationally in the 1920s and 1930s” (2009, p. 7). Focusing on other groups, Iriye emphasizes that, “with a few exceptions … both intergovernmental organizations and international nongovernmental organizations stopped functioning during the war. … The growth of international organizations in the aftermath of the Great War was not so much a reaction against the brutal and senseless fighting as a resumption of an earlier trend that had been momentarily suspended” (Iriye 2002, pp. 19–20). |

| 14 | The American Board also had a major office in New York, which it sought to expand in the years before the war. Cornelius Patton to the Corporate Members of the American Board, 12 June 1912, box 27, folder 8, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records. |

| 15 | Indeed, about twice as wealthy (as measured by annual donations) and twice as large. The BFM was the largest foreign mission board in the United States. The American Board was comparable in size to the boards of other large denominations outside the former Confederacy (e.g., Adventists, American Baptists, and Methodists). |

| 16 | Though one could equally say that the American Board was an outlier in that it had six executive officers, while the BFM and almost every other American foreign mission board employed four. Fred C. Klein, “Report of Committee on Credentials”, in “Report of the Committee on Home Base”, [1912], box 27, folder 5, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records. |

| 17 | Regarding the federal government’s efforts to increase charitable giving during the war, Olivier Zunz writes, “The intensity of the effort reinforced the perception that giving was part of being an American” (2012, p. 56, see also pp. 56–66). |

| 18 | Zunz, exemplifying a tendency among many scholars, briefly notes the history of giving through churches before turning to focus on “occasions … when fundraisers … bypassed the church and lodge” (Zunz 2012, p. 44, see also pp. 44–55; Cutlip 1965, chp. 1–3). |

| 19 | Robert Speer to David G. Wylie, 23 December 1912, box 50, folder 15, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records. |

| 20 | While this section focuses on centralized giving within the Presbyterian Church, other bodies (including the Foreign Missions Conference of North America, the Laymen’s Missionary Movement, and the Missionary Education Movement) were promoting interdenominational fundraising campaigns. In the case of an interdenominational campaign, the funds would go to denominational church bodies, but participating denominations would all adopt the same themes, promotional texts, and timelines. In 1914–1915, for instance, the theme was to be “the social force of Christian missions” and William Faunce’s The Social Aspect of Foreign Missions (1914) was to be the key text for church groups to read. See, for example, “Minutes of the Meeting of the Committee of Twenty-Eight” and “Report of the Committee of Twenty-Eight”, 1914–1916, Foreign Missions Conference of North America Records, NCC RG 27, box 3, folder 11, Presbyterian Historical Society, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. |

| 21 | Control over women’s fundraising was a longstanding issue that had originally quashed women’s efforts to create their own interdenominational boards. Only a few years after World War I, the male-dominated denominational boards would force the women’s boards into mergers, further asserting their control of women’s financial resources (Robert 1997, pp. 129, 302–7). |

| 22 | Indeed, that was precisely the point of cooperative plans. The plans overcame the greater appeal of some endeavors over others, permitting a more systematic budgeting process without impacting the methods of raising money. |

| 23 | A. Woodruff Halsey to Members of the Executive Committee, 12 October 1914, box 50, folder 17, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records. The American Board felt similarly, as Home Secretary Cornelius Patton underlined, “We cannot afford to have this work merged in their minds with that of the other denominational agencies, simply one more thing that Congregationalists are doing”. Cornelius Patton to James Barton, 18 September 1915, ABC 4.1, vol. 23, ABCFM Archives. |

| 24 | Abolition of the Joint Executive Committee, 1913–1915, box 50, folder 17, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records. |

| 25 | “Sixth Annual Report”, [1917], box 51, folder 4, Ecumenical and Relations Records. |

| 26 | The methods that Hubbard described only continued to expand in complexity and systematization (Leach 1958, pp. 219–28). |

| 27 | “Tentative Rough Outline of a Report on the Missionary Outlook in the Light of the War”, n.d., box 30, folder 14, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records. |

| 28 | Mabel E. Emerson to Theodore H. Wilson, 28 September 1914, ABC 4.2, vol. 11, ABCFM Archives. The ship would remain in Sydney harbor for the duration of the war. |

| 29 | Cornelius Patton to Edward Lincoln Smith, 4 August 1914, ABC 4.1, vol. 20, ABCFM Archives. |

| 30 | Patton to Eddy, 27 August 1914. |

| 31 | Patton to Smith, 4 August 1914. |

| 32 | Arthur Brown “to the Missions”, 27 August 1914, box 6, folder 23, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records. |

| 33 | Arthur Brown to [Presbyterian missionaries], 30 December 1914, box 6, folder 23, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records. |

| 34 | It should also be noted that nationality sometimes mattered less than one’s native language. Despite “emphasizing that Dr. Haeberlin and myself were Swiss”, Karl Wittwer complained, “the treatment we received [from the British] was disgraceful and brutal. … We Swiss were treated just like th[e] Germans”. “Report of Missionary Karl Wittwer, A Swiss, Picturing his Experiences during his English Imprisonment”, [1915], box 7, folder 1, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records. |

| 35 | Correspondence between H. Dipper and the Board of Foreign Missions, 12 November 1914 to 22 January 1915, box 6, folders 22 and 24, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records. The American Board also loaned money to a German missionary society in Canton, China. Cornelius Patton to Henry Oliver Hanman, 2 February 1915, ABC 4.1, vol. 22, ABCFM Archives. |

| 36 | [A. Woodruff Halsey] to the West Africa Mission, 17 November 1914, box 6, folder 23, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records; correspondence between A. Woodruff Halsey and Karl Foertsch, 1914–1915, box 6, folders 22 and 24, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records. Both Foertsch’s original German letters and their translations are included in the archive. I base my analysis only on the translated text, which I presume Halsey was responding to. |

| 37 | Correspondence between A. Woodruff Halsey and Karl Foertsch, January–July 1916, box 7, folder 3, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records. |

| 38 | Quote in A. Woodruff Halsey to Jean Bianquis, 8 January 1918, box 7, folder 5, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records; see also other correspondence between A. Woodruff Halsey and the Société des Missions Evangéliques de Paris, 1917–1918, box 7, folders 4–5, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records. |

| 39 | A. Woodruff Halsey to the West Africa Mission, 20 June 1916, box 7, folder 3, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records. |

| 40 | Jean Bianquis to [A. Woodruff Halsey?], 20 October 1916, box 7, folder 3, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records. |

| 41 | For example, A. Woodruff Halsey to Jean Bianquis and reply, 8 October 1917 and 8 December 1917, box 7, folder 4, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records. |

| 42 | Daniel Couve to A. Woodruff Halsey, 11 December 1918, box 7, folder 5, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records. |

| 43 | K. Foertsch to A. Woodruff Halsey, 17 September 1914, box 6, folder 22, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records. |

| 44 | A. Woodruff Halsey to K. Foertsch, 21 October 1914, box 6, folder 22, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records. |

| 45 | Julius Richter to Arthur Brown and reply, 19 February 1915 and 20 March 1915, box 7, folder 1, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records. |

| 46 | Stanley White to Robert Speer, 2 October 1914, box 50, folder 11, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records. See also Brown “to the Missions”, 27 August 1914; and Brown to the Foreign Missions Boards of the United States and Canada, 1 September 1914, box 6, folder 23, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records. |

| 47 | Cornelius Patton to H. W. Luce, 27 August 1914, ABC 4.1, vol. 20, ABCFM Archives. |

| 48 | Committee of Reference and Counsel, “The American Churches and the Great War”, 18 September 1914, box 6, folder 23, Ecumenical Mission and Reference Records. |

| 49 | Robert Speer to S. G. Monfort, 28 September 1914, box 50, folder 11, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records; see also Officers of the BFM to the missions, 1 October 1914, box 6, folder 23, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records. |

| 50 | Arthur Judson Brown, “Why Foreign Missions Cannot Retrench on Account of the War”, 1 December 1914, box 50, folder 12, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records. See also, Committee of Reference and Counsel, “The American Churches and the Great War”. |

| 51 | Cornelius Patton to A. Amelia Wales, 9 September 1914, ABC 4.1, vol. 20, ABCFM Archives. |

| 52 | Cornelius Patton to Henry Oliver Hanman, 2 February 1915, ABC 4.1, vol. 22, ABCFM Archives. |

| 53 | Margaret Hodge to Robert Speer, 26 May 1914, box 50, folder 11, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records. |

| 54 | Circular to Women’s Boards’ Presidents, 7 October 1914, box 50, folder 10, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records; See also Officers of the BFM to the missions, 1 October 1914. |

| 55 | Mary Wood to Robert Speer, 18 May 1914, and Henrietta Hubbard to Robert Speer, 22 May 1914, box 50, folder 11, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records. |

| 56 | In fact, a controversy arose shortly after the start of the campaign because the Presbyterian General Assembly adopted the same name for its own debt-raising scheme, also before the start of hostilities and apparently, somehow, unaware that the BFM was already using the name. Stanley White to Maitland Alexander, 25 June 1914, box 50, folder 11, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records. |

| 57 | Though the cover offers a particularly graphic example of the use of militarism, the rhetoric used within the issue could equally prove the point. Encouraging participation in the EMC, Robert Francis Coyle identified the church as an army with “every member on the firing line”. “Close up the ranks, Presbyterians! Should to shoulder, heart to heart, hand to hand for our great Captain! Be it our glory to be soldiers in that army that will never lower its colors until the whole world swings into the train of Jesus. Forward, the whole company! Forward, with Christ!” (Coyle 1914, p. 5). Militarism was, in fact, so ubiquitous within missionary rhetoric that an exhaustive analysis could fill a book. The point here is to underline how seamlessly the Presbyterian BFM could integrate the European War into its fundraising appeals. |

| 58 | “Sacrificial Emergency Call of the Presbyterian Church”, [December 1914], box 50, folder 10, and Maitland Alexander, “Sacrificial Emergency Call”, 1 December 1914, box 50, folder 12, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records; (Alexander 1915, p. 14). |

| 59 | Robert E. Speer to the Members of the Shadyside Presbyterian Church, 13 February 1915, box 50, folder 12, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records. |

| 60 | “Examples of Self Denial”, [1915], box 50, folder 12, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records. |

| 61 | A. Woodruff Halsey to the Pastors of the Pittsburgh Presbytery”, 25 February 1915, box 50, folder 12, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records. |

| 62 | Circular to the New York Presbytery, 28 November 1914, box 50, folder 10, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records. |

| 63 | “War Emergency”, [October 1914], box 50, folder 10, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records. |

| 64 | Unsigned circular letter, [November 1914], box 50, folder 11, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records. |

| 65 | “Extra War Emergency Bulletin”, January 1915, box 7, folder 1, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records. |

| 66 | Ibid. |

| 67 | Arthur Judson Brown, “Why Foreign Missions Cannot Retrench on Account of the War”, 1 December 1914, box 50, folder 12, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records. |

| 68 | “Extra War Emergency Bulletin”. |

| 69 | William P. Schell and A. Woodruff Halsey to the Executive Council and the Assistant Secretaries, 26 March 1915, box 50, folder 12, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records. |

| 70 | A. Woodruff Halsey and Russell Carter, Circular “To the Members of the Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A.”, 15 May 1915, box 50, folder 12, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records. |

| 71 | E. M. Dodd to Robert Speer, 30 June 1917, box 7, folder 4, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records. |

| 72 | James Barton to Arthur Brown, 1 February 1917; Barton to Stanley White, 8 February 1917; Barton, Bulletin on Turkish Situation, 10 February 1917, box 7, folder 4, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records. |

| 73 | Arthur Brown to Enoch Crowder, 24 May 1917, box 27, folder 2, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records. |

| 74 | Brown to Crowder, 24 May 1917. |

| 75 | Arthur Brown to the Secretaries of Boards and Societies of Foreign Missions in the United States, 27 May 1917, box 27, folder 2, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records. |

| 76 | “The World War and Presbyterian Foreign Missions”, October 1917, box 7, folder 4, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records. |

| 77 | James Barton “to the Missionaries of the American Board at Home and on the Field”, 4 October 1918, ABC 11.4, box 2, folder 5, ABCFM Archives; Arthur Brown to the Colombia Mission, 16 October 1918, box 7, folder 5, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records. |

| 78 | Bayard Dodge, “Personal Report of the Needs for Red Cross Work in Syria”, [1915], box 6, folder 24, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records. |

| 79 | “Cablegrams from Constantinople Regarding Red Cross and Red Crescent Relief”, 23 March 1916, box 7, folder 3, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records. |

| 80 | Arthur Brown to the Colombia Mission, 16 October 1918. |

| 81 | Vance C. McCormick to William Schell, 3 January 1918, box 7, folder 5, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records. |

| 82 | Edwin Bulkley to George Scott, 26 June 1917, box 7, folder 18, Ecumenical Mission and Relations Records. |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Libson, S.P. “Vibrating between Hope and Fear”: The European War and American Presbyterian Foreign Missions. Religions 2018, 9, 205. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9070205

Libson SP. “Vibrating between Hope and Fear”: The European War and American Presbyterian Foreign Missions. Religions. 2018; 9(7):205. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9070205

Chicago/Turabian StyleLibson, Scott P. 2018. "“Vibrating between Hope and Fear”: The European War and American Presbyterian Foreign Missions" Religions 9, no. 7: 205. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9070205

APA StyleLibson, S. P. (2018). “Vibrating between Hope and Fear”: The European War and American Presbyterian Foreign Missions. Religions, 9(7), 205. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9070205