Impossible Subjects: LGBTIQ Experiences in Australian Pentecostal-Charismatic Churches

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Background to the Research

3. Those Who Stayed: LGBTIQ in Ministry

About a year into being in the [name redacted] church and at the beginning of being on staff there, I was appointed a female mentor. Part of her role was to keep me accountable with my sexuality. … I did not participate in any formal conversion therapy but I did see a counsellor for some time that was recommended to me by the church. The counsellor was sought for other reasons but my sexuality certainly came up. She never tried to convert me and encouraged me to explore where I stood with my sexuality.

I don’t tell people. A situation happened the year I started at [church name redacted] that my pastor was told by people that used to know me, that were trying to get me to change back. … But he basically stopped and went, “No. You know what? Talk to me. Tell me your story.” And I went, “This is it.” And he went, “I don’t understand it, but I’m not going to reject you. I want you to still stick around the church.” There are things, like because I’m not allowed to get up on the pulpit, I’m not allowed to be in the musicians—I can do the sound, but I can’t get up and sing, you know, and do those sort of things—but it’s a journey for them as much as it is for me.

If anything, I’d like to change their opinions, at times, in relation to—some of them can be very, I won’t say dogmatic—but just take the fact that I’m a transgender, it’s the sheer fact that if people find out, suddenly I’m ostracised because of it.”

So I knew [my former church] like the back of my hand … I had grown up in this place. I had an all-access pass. I had a key to pretty much every door … It was about the same time [the leader] was identifying the language to use about the church and … [they] kind of had this concept of a foyer space … a living room space, a kitchen space, and they have different levels of intimacy. So a foyer space is kind of like a weekend service for a guest-type person. Anyone is welcome to the foyer. I think a living room was to do with shared interests. So like a small group. And a kitchen space was, like, very intimate, so your very close group of friends or volunteering or leadership, and things like that. The core was, if you’re a practising homosexual (… there was no concept of LGBTI or anything like that …) you were welcome but not affirmed. So, “We want you, we love you, and you’re welcome, and we want you to come to our church, but effectively that’s where it ends. If you want to be part of the church, you … can be gay, but you have to be celibate” … That’s the line. 8

I know people who love me deeply, and I feel deeply loved by them, and you know, … we’ll get together and we’ll pray and we’ll worship and we’ll fellowship, and it’s beautiful, and the presence of God is so there. And yet if I were to go and get … romantically involved with another [person of the same gender], like, they would sit down with me and be like, “Hey, what’s going on?”

By and large, people have been really accepting and embracing of me as a person and me as a human being, with all of my struggles, and they’ve been really understanding and really supportive … I couldn’t be happier with the way in which people have journeyed with me, because … it’s not been this on the front foot, proactive, hands-on approach where they’re trying to fix me and I’m their project of sorts.

[God] may very well do a work within my heart and within my mind and within my life that shifts the desires I have, and all of a sudden … I find one day down the track … I do desire to be with a [member of the opposite sex] and to have a [spouse] and all of that normal stuff that comes with a family.

There’s my pastor, my missions pastor, and a few of my good friends in church. They’re supportive for my change. They don’t—they don’t agree with it, and neither do I, so we’re all supportive for my transformation and my change … Nobody agrees with this lifestyle, so just to make that clear. Everyone supports my journey of healing, not my journey into it, if that makes sense … So yeah, they’re all praying for me to get healing and continue to live a celibate life, and I … hope to get healed one day.

4. The Devil Made You Do It: PCC and SOCE

[My pastor said] that I had been deceived by the devil and followed a false prophet … that I had then been convinced that I was a homosexual and chosen to live a sinful lifestyle, and that if I wanted to have any active part in leadership or in the church, I had to repent, and either go through therapy or be celibate for the rest of my life.

When my awareness around my sexuality came up, I was in deep, deep trauma … I really split myself between my belief in a God that I believed was all-powerful and connecting to an amazing community that I was within, whilst at the same time I had a deep, deep, deep, dark, hidden secret—which, through teaching at [Church name redacted], was attributed to Satan, demons, the devil, and evilness. So I constructed for myself a really big sort of duality of good and evil.

Interviewer: The next question is, have you ever been encouraged or coerced by anyone in your church, or anyone at all, to participate in conversion therapy?

Phoenix: No. The only thing I can say is when I … before transition, when I was going to [Church name redacted], I had—one of the pastors there believed I had a demonic spirit in me for homosexuality and tried to pray it out of me.

Interviewer: So, have you ever been encouraged or coerced by anyone, either in your church, or anybody at all, to participate in conversion therapy?

Gabriele: What’s conversion therapy?

I: So conversion therapy, or ex-gay ministry, sometimes it’s called, is a ministry that is aimed at helping people transition or change their sexual preference or identity.

G: Well, that’s what counseling is. When you go to a Christian counselor you can expect that they’re going to help you walk with Jesus, so not to be a homosexual. To be the opposite.

I: Mm, hmm. And you mentioned—

G: Whatever the opposite is for you, whether it’s heterosexual or not. Whether that’s heterosexual or not, you just can’t be homosexual. So I wouldn’t call that conversion therapy.

I: You wouldn’t call it conversion therapy. Okay. You mentioned Exodus and Living Waters. Can you tell me a bit more about your experience of those?

G: They’re fantastic. They bring in the Holy Spirit, the word of God. They don’t directly say, you know, you have to be a certain way, they just basically lead you and guide you by the Holy Spirit how to live with Jesus, and whatever addiction you have, whether it’s sexual or not—you can put yourself in there quite safely.

So you’re in small groups, and you get to share your own personal testimonies. And everyone did it when I did it, which was nice, because then you realised, “Oh, I’m not that different to others” … Even though I struggle with this, they struggle with that, and so we could all support one another.

I found the group to be quite encouraging. For the first time in ten years I was working alongside other young men who were facing a similar struggle to my own and who also wanted to do something about it. I made some good friends without the need for sexual intimacy.

[T]his kind of terminology is an attempt to make the message more palatable to the seeker of help and as a defence to those opposing SOCE work … the underlying message remains the same—“homosexuals are broken people and God can fix them.”

It [Living Waters] all produced endless introspection and confession, and a religious obsession that starts to get really uncomfortable and detached from reality … There are smiles and laughs, but underneath it all is a heavy intensity that slowly keeps piling up guilt and shame, or should I say slowly repressing overt guilt and shame until unreality sets in, often resulting in depression and a constant nagging that you can never live up to God’s standard, eventually creating a far more serious and deeper dissonance than before, with absolutely no hope of being yourself or living with personal integrity. It effectively shuts down the most basic and fundamental parts of our makeup behind a wall of religious activity … Without exception, every person who I have spoken to or observed, claiming to be transformed, simply denies that there is a problem anymore, even though they still have to wrestle with same sex attraction … There are some who have a semblance of honesty and just refuse to act on their inherent sexuality, claiming celibacy is the only option, until they have achieved the magical goal of becoming straight, if ever. Most however, delegate their same sex attraction to the same basket as any sinful thought, and keep repenting and standing on God’s apparent promises of healing.

I wish I’d known then that you could be gay and Christian, and I wish I’d known other people and other stories that had communicated that to me. Because for me, it was come out and lose God, lose your friends, lose hope, lose a good life, or don’t come out, try to change, go through this stuff, and you can still keep God, you can still keep your church, you can still keep your friends. You may have a [spouse] one day, you may have kids one day … It was definitely my choice, but at the same time it was kind of like, you know, what other choice did I have? … I wish that churches—even though I know they don’t do this now—but I wish that churches could offer almost like a balanced view … I would hope that churches don’t recommend that anyone do conversion therapy or ex-gay programs or anything like that now. I hope that that doesn’t happen. But I think if they were to offer a view and say, “Yeah, you can be gay and Christian, and we support you, and we want to encourage you in your faith regardless of if you’re gay or straight,” I think that would be so much more helpful.

5. Those Who Left: Able to Breathe

There are so many other accounts where I’ve been in churches and laid hands on the sick and seen supernatural healing come to people, and medically verified. One lady had cancer. It … was bladder cancer, and it got to the point that it had rapidly spread to … other parts of her body … It was a long, long time, probably over a year, that we were praying for her. And she came straight to me, because in the church environment, these sort of encounters weren’t happening for anybody else, but they were happening for me.

So I was essentially put on a pedestal, and put on the, on a prayer team, and put on the leadership team in outreach, and put on—even if that was short-lived, because I came out of the closet (laughs).

I think the biggest challenge is fighting for who you are, you constantly feel like you are not good enough to be there and no longer do people look at you the way they once did. I was no longer allowed on kid’s ministry. I couldn’t talk to the youth about it; I couldn’t share my struggles because I “refused” to change. But, an adulterer, porn addict, an ex-drug addict and ex-prostitute could. They could even get on stage and share about their experiences, but not me. I had to be quiet. That’s the battle: Not only are you fighting in your own head, but you are fighting an entire belief system that has previously told you, you are loved and that God will meet you wherever you are at.

I started to talk to some really good and trustworthy friends of mine who were incredible, and to this day I owe them my sanity. They would tell me that I was amazing, loved, and that my sexuality didn’t mean I was a bad person. But no matter how hard I tried, I couldn’t admit it. The fact was, Christianity told me it was “wrong,” “sinful” and “not what God intended for me.” I hurt, thinking I was hurting God. Whilst talking to my friends, I would cry, get choked up and become so enraged with myself for feeling this way! I wanted to be straight so bad. But I was realising that it just was not who I was.

It was actually being able to breathe, and … for me, it was like having my head underwater my whole life and then finally being able to gasp for air, and finally just fill my lungs with air and breathe, and just finally breathe.

I had become a Christian and was sure God loved me and was with me, but I guess this created doubt over the years of hearing it, and I never really bought into the fact that Christians loved gay people as much as they said when they said things like “Hate the sin not the sinner.” Being who I knew myself to be on the inside, I doubted people would love me as much if they knew, and that they would focus on trying to change me if I said anything. I lost a couple of close friendships when I did try, and all this chipped away at how God might view me. I know better now and am comfortable with myself, but I do the feel the loss of the divine relationship I once had. I don’t blame that primarily on being part of a PCC church, but it has played a part.

6. Pentecostalism and LGBTIQ in Australia

It was the coming of the Spirit that commissioned people for ministry—and He was coming not only to men, but to women, too. So ordination was no longer a gender issue. If God Himself had anointed someone with the Spirit, what further endorsement did they need?

7. Opening up about PCC and LGBTIQ Members

I’ve had my challenges, but it’s been in some ways, I think, more challenging for those around me to know how to counsel me, how to walk with me, how to shepherd me, how to love me appropriately in the midst of it all.

And I looked for a church for a year, and then in Easter 2011, I played piano at a church, [Church name redacted] … I was asked there by the pastor’s wife, and she was also a worship leader, and I’ve been playing piano there ever since. I was on the board of the church for a while there as well. They knew I was gay from the start. But then, when I explained to them that I’m prepared to date, I think that … frazzled them a tiny bit. And then they actually asked me if I could share my story recently, so a month ago I actually shared in church, and in that experience they asked me to step down from the board so it wasn’t too confronting for members if they got upset.

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abraham, Ibrahim. 2009. ‘Out to get us’: Queer muslims and the clash of sexual civilisations in Australia. Contemporary Islam 3: 79–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Christian Churches. 2014. Available online: http://www.acc.org.au/about-us/ (accessed on 7 December 2017).

- Barton, Bernadette. 2012. Pray the Gay Away: The Extraordinary Lives of Bible Belt Gays. New York: NYU Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chant, Barry Mostyn. 2000. The Spirit of Pentecost: The Origins and Development of the Pentecostal Movement in Australia 1870–1939. Lexington: Emeth Press. [Google Scholar]

- Clifton, Shane. 2009. Pentecostal Churches in Transition: Analysing the Developing Ecclesiology of the Assemblies of God in Australia. Leiden and Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Couch, Murray, Hunter Mulcare, Marian Pitts, Anthony Smith, and Anne Mitchell. 2008. The religious affiliation of gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender and intersex Australians: A report from the private lives survey. People and Place 16: 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Dayton, Donald W. 1987. Theological Roots of Pentecostalism. Peabody: Hendrickson Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas-Meyer, Graham. 2014. You Shall Walk in the Dark Places: My Story—Resolving My Sexuality and My Faith. Beeliar: The Love of God Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, Peter. 2012. Nineteenth-century Australian charismata: Edward Irving’s legacy. Pneuma 34: 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedom2b. n.d. Available online: https://freedom2b.org/ (accessed on 18 July 2016).

- Grenz, Stanley James. 1998. Welcoming but Not Affirming: An Evangelical Response to Homosexuality. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gresham, Benny. 2012. Breakfast with Brian: Hillsong, Homosexuality and the Future. Available online: http://bennygresham.blogspot.com.au/2012/05/breakfast-with-brian-hillsong.html (accessed on 19 January 2018).

- Henrickson, Mark. 2007. A queer kind of faith: Religion and spirituality in lesbian, gay and bisexual New Zealanders. Aotearoa Ethnic Network (AEN) Journal 2: 6. [Google Scholar]

- Hillier, Lynne, Anne Mitchell, and Hunter Mulcare. 2008. ‘I couldn’t do both at the same time’: Same sex attracted youth and the negotiation of religious discourse. Gay & Lesbian Issues and Psychology Review 4: 80–93. [Google Scholar]

- Hollenweger, Walter J. 1997. Pentecostalism: Origins and Developments Worldwide. Peabody: Hendrickson Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Jennings, Mark. 2017. A silence like thunder: Pastoral and theological responses of Australian pentecostal-charismatic churches to LGBTQ individuals. In Annual Review of the Sociology of Religion: Pentecostals and the Body. Edited by Michael Wilkinson and Peter Althouse. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 217–38. [Google Scholar]

- Kirby, Michael. 2013. Clobbering Religious Gay Prejudice. Available online: https://www.eurekastreet.com.au/article.aspx?aeid=36395 (accessed on 19 January 2018).

- Marjoram, Jim. 2017. It’s Life Jim… One Man’s Story of "Coming out:" Unravelling Religion, Sexual Identity and Personal Integrity, 3rd ed. San Bernadino: James Marjoram. [Google Scholar]

- Ngai, Mae. 2004. Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 2013. Group Apologizes to Gay Community, Shuts Down ‘Cure’ Ministry. Available online: http://edition.cnn.com/2013/06/20/us/exodus-international-shutdown/index.html (accessed on 20 January 2018).

- Riches, Tanya Nicole. 2016. (Re)imagining Identity in the Spirit: Worship and Social Engagement in Urban Aboriginal-Led Pentecostal Congregations. Ph.D. dissertation, Fuller Theological Seminary, Pasadena, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Sowe, Babucarr J., Jac Brown, and Alan J. Taylor. 2014. Sex and the sinner: Comparing religious and nonreligious same-sex attracted adults on internalized homonegativity and distress. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 84: 530–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venn-Brown, Anthony. 2014. Living Waters Australia to Close. Available online: http://www.abbi.org.au/2014/03/living-waters-australia/ (accessed on 23 August 2017).

- Venn-Brown, Anthony. 2015. Sexual orientation change efforts within religious contexts: A personal account of the battle to heal homosexuals. Sensoria: A Journal of Mind, Brain & Culture 11: 81–91. [Google Scholar]

- Vines, Matthew. 2014. God and the Gay Christian: The Biblical Case in Support of Same-Sex Relationships. New York: Convergent Books. [Google Scholar]

- Wacker, Grant. 2001. Heaven below: Early Pentecostals and American Culture. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, Michael. 2017. Pentecostalism, the body, and embodiment. In Annual Review of the Sociology of Religion: Pentecostals and the Body. Edited by Michael Wilkinson and Peter Althouse. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 17–35. [Google Scholar]

- Wink, Walter, ed. 1999. Homosexuality and the bible. In Homosexuality and Christian Faith: Questions of Conscience for the Churches. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, pp. 33–49. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | At the time of writing, I have not interviewed any Intersex informants. |

| 2 | This term was coined by Ibrahim Abraham, who recognises queer Australian Muslims as similar impossible subjects—a configuration of sexuality and spirituality ‘impossible’ in heteronormative understandings of Islam (Abraham 2009). See also (Ngai 2004). |

| 3 | The passages often quoted in support of the sinfulness of same-sex attraction and/or relations (as an example of one LGBTIQ issue) are: Genesis 19; Leviticus 18:22 and 20:13; Romans 1:18–32; 1 Corinthians 6:9–10; 1 Timothy 1:9–10; and Jude 6–7. Some LGBTIQ Christians refer to these as “clobber passages,” as they have been used in the past to exclude same-sex attracted people from faith and ministry (Gresham 2012; Kirby 2013). In doing this, it is fair to say that several of these texts have been taken out of context, and many have pointed out some of the hermeneutic challenges associated with these passages. Nevertheless, as Walter Wink (1999) has indicated, there are at least three texts in the Biblical canon that appear, when applying sound hermeneutic critique, to unequivocally condemn same-sex romantic and sexual relations. They are Leviticus 18:22; 20:13; Romans 1:18–32: Walter Wink, “Homosexuality and the Bible,” in Homosexuality and Christian Faith: Questions of Conscience for the Churches, ed. Walter Wink (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1999), 33–49. |

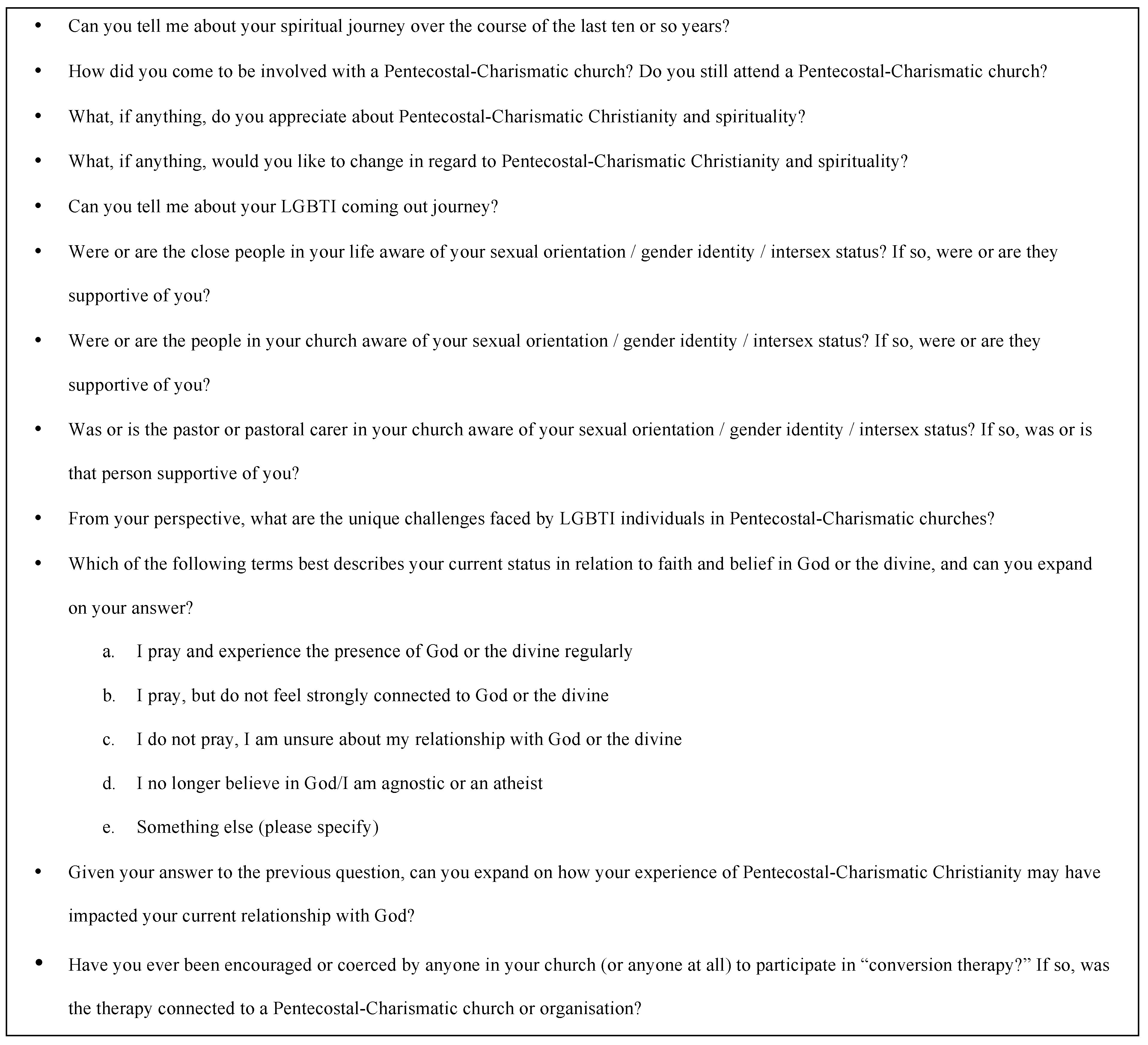

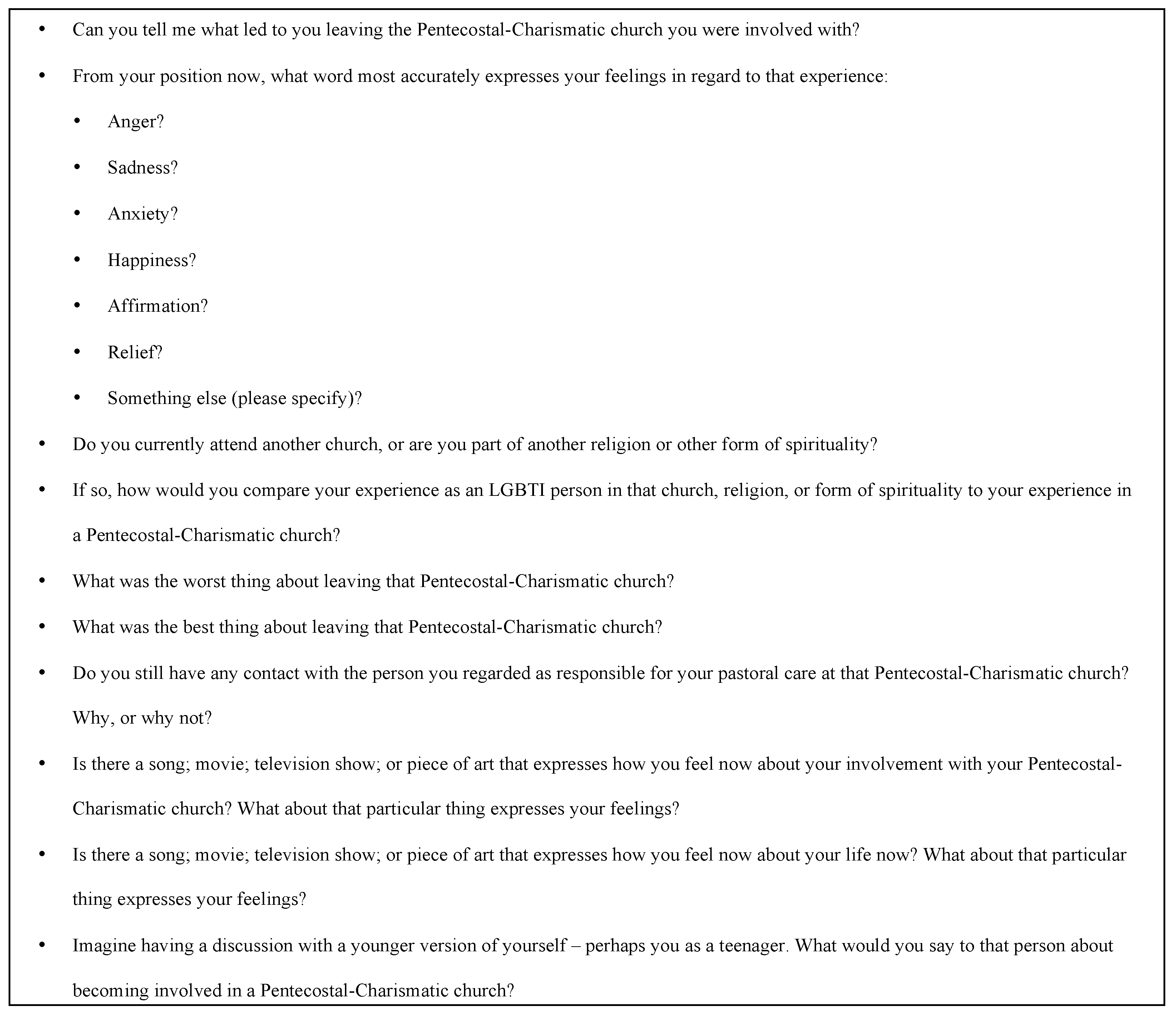

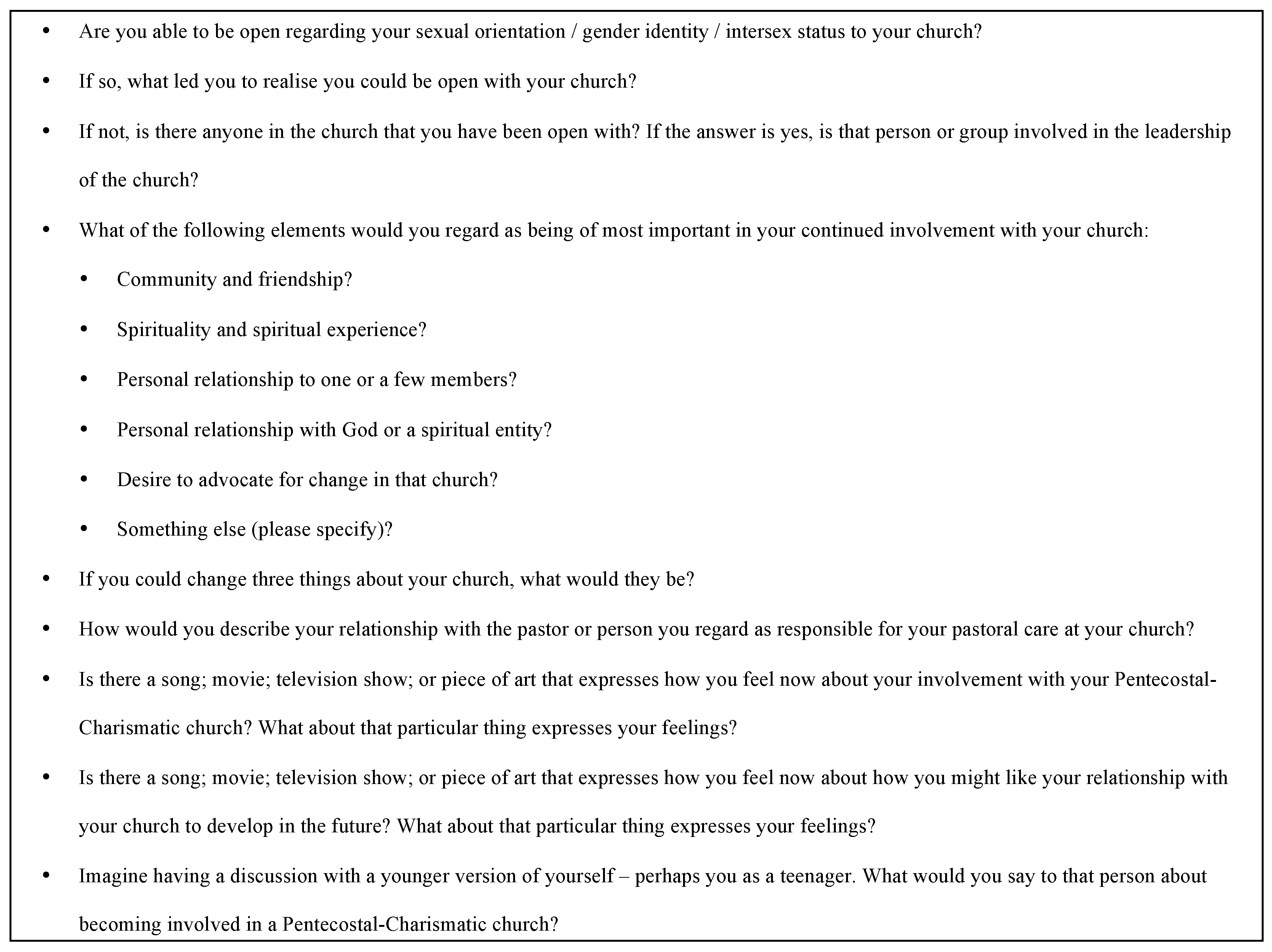

| 4 | Interviews will continue until “data saturation”: namely, the point at which no new themes or unfamiliar narratives are emerging from interviews is reached. My initial proposal was to complete 20 in-depth interviews with PCC pastors and 30–50 interviews with LGBTIQ participants. |

| 5 | This is a qualitative study, employing non-probability sampling, and hence makes no claims to being representative of all LGBTIQ experiences of PCC in Australia. |

| 6 | Please note that throughout this paper, gender-specific pronouns have been eschewed in favor of the non-gendered “they”, “them,” or “their,” even when referring to singular entities. For the sake of readability, I have endeavoured to keep this to a minimum. |

| 7 | Transgender people can be straight, gay, lesbian or bisexual. For instance, a trans man who is attracted only to women would identify as straight. |

| 8 | The phrase “welcome but not affirmed” differentiates churches wherein LGBTIQ people are fully included in church life and ministry from those churches that “welcome” LGBTIQ people, but do not “affirm” their sexuality or gender. The late Stanley Grenz outlined this position in the book of the same name (Grenz 1998). |

| 9 | The Australian arm of Living Waters officially ceased operations in 2014, and Exodus International officially ceased operations in 2013 (Venn-Brown 2014; Payne 2013). However, as Venn-Brown indicates, there remain a “handful of organisations” offering SOCE in Australia, possibly using the same methods and approaches as Living Waters and Exodus (Venn-Brown 2015). |

| 10 | Mark Henrickson makes a similar point, praising the resilience of LGBTIQ people in remaining faithful to traditions that have in many cases abandoned them (Henrickson 2007). |

| 11 | Other than Seymour, the individual most often cited as the pioneer of Pentecostalism in the United States is Charles Fox Parham, founder of Bethel Bible School in Topeka, KA, where Agnes Ozman first exhibited glossolalia on New Year’s Day, 1901. Parham’s legacy is complicated, particularly in terms of this paper, as he was arrested in 1907 on charges of sodomy. The charges were dropped, and Parham always insisted that he had been framed. Walter Hollenweger’s comment is worth noting: “It seems to me that, until further evidence is presented, Parham should be considered as having been ‘not guilty as charged.’ Furthermore, the Parham story (and other similar stories) might sometime stimulate Pentecostals to theologically re-examine their approach to homosexuality, especially in the light of newer theological and medical evidence” (Hollenweger 1997). |

| 12 | Apart from the aforementioned Aboriginal-led Pentecostal congregation in Innisfail, which predates Good News Hall, recent research by Peter Elliott indicates that the antecedents of Australian Pentecostalism should be traced to the arrival of representatives of Edward Irving’s Catholic Apostolic Church (a Christian group who embraced the “charismatic gifts”) in Melbourne in 1853 (Elliott 2012). |

| 13 | It is also important not to paint too rosy a picture of Pentecostal acceptance of women in ministry. As Grant Wacker has pointed out, with reference to the American context, such “roseate portraits” can minimize the sociological and theological challenges many women had to negotiate in the early days of the movement (Wacker 2001). |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jennings, M.A.C. Impossible Subjects: LGBTIQ Experiences in Australian Pentecostal-Charismatic Churches. Religions 2018, 9, 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9020053

Jennings MAC. Impossible Subjects: LGBTIQ Experiences in Australian Pentecostal-Charismatic Churches. Religions. 2018; 9(2):53. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9020053

Chicago/Turabian StyleJennings, Mark A. C. 2018. "Impossible Subjects: LGBTIQ Experiences in Australian Pentecostal-Charismatic Churches" Religions 9, no. 2: 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9020053

APA StyleJennings, M. A. C. (2018). Impossible Subjects: LGBTIQ Experiences in Australian Pentecostal-Charismatic Churches. Religions, 9(2), 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9020053