Abstract

While metaphors for the human mind have been intensively discussed across multiple disciplines, there remains a gap on how Buddhism deals with the mind metaphorically. This study explores how Mahāyāna Buddhist discourse resorts to embodied and discursive metaphors in describing and explaining the mind. Buddhist texts analyzed are the Treatise on the Awakening of Faith According to the Mahāyāna and its two commentaries by Wŏnhyo. The Awakening of Faith discourse abounds in metaphors for the sentient being’s mind in two aspects: the ordinary phenomenal mind and the transcendental essential mind. The focus of this study is on the relationship between the seemingly opposing two minds, and the ways in which these two opposites are unified metaphorically. To do so, I first examine how the essential mind, which is said to transcend ordinary experience and verbal expression, is made speakable through primary metaphors and NON-CONTAINER (unboundedness) image schema, and how the phenomenal mind is metaphorically understood according to the covarying scalar properties in primary metaphors. With respect to the argument for harmonizing the two minds, in which introducing more apt analogical metaphors is important, two representative discursive metaphors (a mirror metaphor and an ocean metaphor) are compared and discussed.

1. Introduction

There has been a considerable amount of academic attention paid to the metaphoric nature of how we talk about the human mind, which is invisible and elusive. Special attention was paid to the metaphors for the mind in philosophical and scientific discourses (e.g., Draaisma 2000; Gentner and Grudin 1985; Kearns 1987; Leary 1990; Rasskin-Gutman 2009; Sternberg 1990; Turbayne 1991; Valle and Eckartsberg 1981). Much of the discussion has concerned the role of metaphors in building theories of the mind, including consciousness, intelligence, and memory. There has also been interest in metaphors for the mind in fiction and poetry (e.g., Kearns 1987; Pasanek 2015) and everyday communication (e.g., Barnden 1997). The metaphorical conceptualization of the mind and its mental processes in bodily and physical terms has been one of the main interests within the field of cognitive linguistics, particularly conceptual metaphor theory (CMT). This is understandable given that CMT (e.g., Lakoff 1993; Lakoff and Johnson 1980, 1999, 2003; for recent controversies, also see Gibbs 2017; Kövecses 2015) is largely based on the principles of embodied cognition, which means that “metaphorical concepts are rooted within recurring patterns of bodily activity that serve as source domains for people’s metaphorical understandings of many abstract concepts” (Gibbs 2017, pp. 6–7). Indeed, our mind is an example of an abstract, invisible, and incorporeal entity or process par excellence, but treated as concrete, visible, and corporeal. As Lakoff and Johnson note, “[it] is virtually impossible to think or talk about the mind in any serious way without conceptualizing it metaphorically” (Lakoff and Johnson 1999, p. 235). They assert that while a purely literal conception of the mind enables only an impoverished skeletal understanding of it, any detailed reasoning about mental acts, such as thinking, perceiving, and believing, makes metaphors necessary (Lakoff and Johnson 1999, p. 266). A broad range of metaphors conceptualizing human mental processes in terms of their bodily processes was called the MIND IS BODY1 metaphor by Sweetser (Sweetser 1990; see also Dancygier and Sweetser 2014). This conceptual metaphor system is outlined by Lakoff and Johnson (1999, pp. 235–43) as follows: THINKING IS MOVING, THINKING IS PERCEIVING, THINKING IS OBJECT MANIPULATION, and ACQUIRING IDEAS IS EATING. Lakoff and Johnson (1999) also provide a detailed discussion on mind metaphors, such as MIND IS A CONTAINER, MIND IS A PERSON, MIND IS A BUILDER, MIND IS A MACHINE, MIND IS A COMPUTER, and KNOWING IS SEEING. They argue that this ordinary mind metaphor system provides the basis and raw material for the major Western philosophical theories of mind.

This paper is concerned with the metaphorical conceptualization of the mind in a culturally different context, that is, in a Mahāyāna Buddhist discourse. According to the canonical texts, Buddhism is primarily concerned with freeing all sentient beings from suffering and bringing them to ultimate happiness. According to Buddhism, suffering is caused by certain states of mind, including ignorance, craving, hatred, and attachment. Therefore, the main concern of Buddhism is to discern the true nature of mind and how we can transform and purify our ordinary conditioned mind. As such, it is not surprising that the religious discourse of Buddhism, especially the Mahāyāna strand, is replete with statements about mind and consciousness. This prompts the question: Are there any similarities or differences in metaphors between the human mind as ordinarily experienced, and the mind as religiously conceptualized? In the context of ordinary metaphors for the mind such as container, and in the background of the classical sciences of mind, in which the computer metaphor has been dominant, Buddhist metaphors create an impression of idiosyncrasy and marginality. However, in the era of second-generation cognitive science, generally called the “embodied cognition” approach (see Shapiro 2014), in which the body or world plays a constitutive role in cognition, scientific insights into the nature of the mind (e.g., the “groundlessness” of self and mind) seem principally compatible with Buddhist philosophy and psychology, as some cognitive and Buddhist scholars (e.g., Austin 1998; Cho 2014; Coseru 2012; Garfield 2015; Thompson 2015; Varela et al. 1991, 2016; Wallace 2007) have pointed out. Given the not unusual interest in the Buddhist model of cognition as an alternative to the Cartesian model in cognitive science, it should prove interesting to investigate how the Buddhist contemplative mind relates to the ordinary experiential mind (and its philosophical and scientific elaborations) with respect to metaphorical cognition.

Religious discourse is generally considered peculiar compared to other modes of discourse because it renders expressible what is claimed to be transcendent, and therefore verbally inexpressible. Thus, the endeavor “to eff the ineffable” (Pinker 2007, p. 277), instead of remaining silent, often makes religious texts fraught with negative statements, as well as seeming contradictions and paradoxes. An important way of coping with such language limitations, however, has traditionally been using figurative language, such as metaphors. Religious metaphors for the divine, the transcendent, or the ineffable have been an intriguing topic for religious studies, philosophy, and other disciplines. However, the analysis of metaphor in religious discourse from a cognitive linguistic perspective, as Dancygier and Sweetser noted, “has barely scratched the surface of this domain” (Dancygier and Sweetser 2014, p. 211). Some pioneering studies in this area (e.g., Boeve and Feyaerts 1999; DesCamp and Sweetser 2005; Dille 2004; Feyaerts 2003; Howe 2006; Howe and Green 2014; Masson 2014) are almost entirely focused on monotheistic religions, such as Judeo-Christian. This study deals with metaphors in Buddhism, another religion of which discourse is also inevitably permeated with figurative language expressing the inexpressible ultimate reality.

Buddhist scriptures and treatises offer rich metaphoric presentations of the ultimate characteristics of reality and soteriological goals. Metaphoric language in Buddhism is one of verbal skills of Buddhas (enlightened beings) and bodhisattvas (beings who seek Buddhahood), the means by which they give expression to their ineffable spiritual experience and make it intelligible to unenlightened beings. While the scholarly literature on metaphors in Buddhist discourse is not so extensive as that on Judeo-Christian metaphors, it has recently begun to grow in the fields of Buddhist and religious studies (e.g., Ciurtin 2013; Covill 2009; Gardiner 2008; Hwang 2006; Kragh 2010; McMahan 2002; Schlieter 2013; Smyer Yu 2012; Weber 2002). However, very little study has been undertaken from the perspective of cognitive linguistics (with the exception of Gao and Lan 2018; Lan 2012; Lu and Chiang 2007; Silvestre-López and Navarro i Ferrando 2017). In contrast to prior work exploring conceptual metaphors in a particular Buddhist sutra or contemporary dharma talk texts, this study is concerned with a core Buddhist topic that is addressed in a specific Buddhist discourse by resorting to metaphor: the enlightened true mind or the Buddha-nature.2

For the purpose of this paper, I have chosen one important Mahāyāna Buddhist text, the Treatise on the Awakening of Faith According to the Mahāyāna (often shortened to the Awakening of Faith) and its two commentaries by the eminent Korean scholar-monk, Wŏnhyo 元曉 (617–686). In this study, I attempt to provide a cognitive semantic analysis of metaphors for the mind and its two aspects—the essential and the phenomenal mind—in the Awakening of Faith discourse. The focus of the discussion is on the relationship between the apparently opposing two minds, and the ways in which these two opposites are reconciled and unified metaphorically. The main body of this paper consists of four sections. After dealing briefly with the characteristics of the data texts and their significance for metaphor analysis in Section 2, Section 3 provides the frame for discussing the relationship between the essential and the phenomenal mind. Based on this, Section 4 focusses on primary (and complex) metaphors for the true mind as contrasted with the ordinary mind. Lastly, in Section 5, I show how the seeming opposition between the two minds is resolved by way of discursive analogical metaphors.

2. Data Texts and Their Significance

As noted, the primary texts of analysis are the Awakening of Faith and Wŏnhyo’s two commentaries thereon. The Awakening of Faith (Dasheng qixin lun 大乘起信論) is a sixth-century Chinese text (T.1666: 32.575a–583b).3 Once thought to be a translation of the Sanskrit original attributed to the Indian author Aśvaghoṣa (circa second century CE), it is now widely assumed to have been originally composed in Chinese, perhaps by the alleged “translator,” Paramārtha (Buswell and Lopez 2014, p. 221).4 Although it is often regarded an apocryphal text, the Awakening of Faith is said to be “one of the most influential texts in all of East Asian Buddhism” (Gregory 1986, p. 64), and has served as the doctrinal bases of Mahāyāna Buddhism in China, Korea, and Japan.

This treatise is commonly understood as an attempt to integrate two of the main teachings in Mahāyāna Buddhist traditions: the teaching of the Buddha-nature within all sentient beings (tathāgatagarbha [embryo or womb of the Buddhas] thought), and that on the foundational “store consciousness” (ālayavijñāna) in the “Mind-Only” (Yogācāra) tradition. The former teaches that all sentient beings possess the Buddha-nature, which makes unenlightened and ordinary beings capable of attaining Buddhahood or enlightenment. The latter explains why our mind is innately impure and deluded, and thus seems far from enlightened. Seeking to harmonize these seemingly incompatible doctrines, the Awakening of Faith is primarily concerned with “one mind with two aspects.” It discusses the complementary and inseparable relationship between the enlightened true mind and the unenlightened phenomenal mind, and explains practices and methods necessary to cultivate a faithful mind and attain Buddhahood.

Nonetheless, since the content of the treatise is presented in a comprehensive and terse form, numerous commentaries have been written on the treatise, including Wŏnhyo’s two commentaries—Commentary on the Awakening of Faith (Taesŭng kisillon so 大乘起信論疏 [T.1844: 44.202a–226a]) and Separate Record on the Awakening of Faith (Taesŭng kisillon pyŏlgi 大乘起信論別記 [T.1845: 44.226a–240c])—which are traditionally regarded as the most influential (Ŭn 1991). Claimed as “[p]erhaps the greatest scholar ever produced across the full panoply of the Korean religious tradition” (Buswell 2017, p. 132), Wŏnhyo made a significant contribution to the development of the East Asian Buddhist tradition, conveying his philosophical and spiritual insights through scriptural exegesis. This is the reason I chose the two commentaries among many other influential ones. In order to facilitate the understanding and glossing of the text, an English translation of the treatise (Hakeda 2006) and a Korean translation of both the treatise and the two commentaries (Ŭn 1991) have also been consulted.

As suggested above, one of the reasons for choosing these texts is that the main theme of the treatise is the explanation of the two aspects of the mind, and how their unification leads to enlightenment. Indeed, approximately half of the treatise deals with this theme, while the rest discusses issues such as the correction of biased views, the aspiration for enlightenment, and the practice with faith. Moreover, a word frequency analysis of the treatise within the NTI Corpus from the Chinese Buddhist Canon reveals that the most frequent lexical word in the text is “xin/sim心” (mind).5 Additionally, Mahāyāna Buddhist treatises (called śāstra; lun/non 論) often use metaphors, although the way in which they present the dharma is commonly explanatory and interpretative. Of course, scriptures (called sutra; jing/kyŏng 經), which are said to report the words or intentions of the Buddha, frequently draw on figurative language to appeal to audiences. Broadly speaking, the most metaphors in the main treatise are repeated or elaborated in the two commentaries. However, the commentaries encompass a wider range of metaphors prevalent in Mahāyana Buddhist discourse (sutras and sastras) for effective explication.

What I mean by the “Mahāyāna Buddhist discourse” in this paper is not a reference to all scriptures, treatises, commentaries, and modern discursive forms of Mahāyāna Buddhism; rather it refers to what may be called “the Awakening of Faith discourse” consisting of the three texts mentioned. However, it would not be an exaggeration to say that the “big” discourse is fundamentally similar to the “little” discourse, as can be inferred from Hakeda’s judgement that the Awakening of Faith is “a comprehensive summary of essentials of Mahāyāna Buddhism” (Hakeda 2006, p. 1). Bearing this in mind, the following sections examine the relationship between the essential and phenomenal minds.

3. Mahāyāna as the Two Aspects of the One Mind

It can be said that the overall issue with which the Awakening of Faith deals is “great vehicle (大乘),” a term translated from the Sanskrit mahāyāna, which literally means “great (mahā; 大) vehicle (yāna; 乘).” The term itself is a metaphorical word, one which typically refers to a religious movement that began in India about four centuries after the Buddha’s death, and became the dominant form of Buddhism in East Asia and Tibet. Of primary importance in this Mahayana Buddhism is the bodhisattva path to Buddhahood, in which the image of a “great vehicle” evokes the notion of a goal to reach (enlightenment) and the means to do so (teachings and practices). That is to say, this vehicle should be so large and so excellent as to transport all sentient beings along the path to enlightenment, particularly in contrast to the so-called “small vehicle (hīnayāna; 小乘),” which is used by those who want to attain enlightenment for themselves alone. Here, we find journey (path or way) metaphors prevalent in Buddhist (and other religious) discourses,6 as the examples below from the Awakening of Faith and its commentaries also show:

- “佛道 the Buddha way” (Buddhism); “菩薩道 the path of the bodhisattva” (the bodhisattva’s path to enlightenment); “進趣大道 to proceed on the Great Way” (to practice according to Mahāyāna Buddhism)

- “法門 dharma gate” (Buddhist teachings as an entrance to enlightenment)

- “因地 cause ground” (the practicing stage of a bodhisattva before attaining Buddhahood); “果地 fruit ground” (the resultant stage of Buddhahood)

- “不退轉 never turning back” (non-retrogression on the bodhisattva path to enlightenment)

- “生死之海 the ocean of birth and death” (samsara as the perilous ocean); “涅槃之岸 the other shore of nirvana” (the state of liberation as the safe harbor)

The verbal expressions above would not make sense without the appropriate metaphoric mappings between the dangerous and difficult journey to the destination in which a proper guide and means are necessary, as well as the practice of Buddhist teachings to attain enlightenment (liberation from suffering).

In the Awakening of Faith, however, the term “mahāyāna (大乘)” actually refers to “the mind of the sentient being (衆生心).” After all, this text is called the “treatise on the awakening of faith according to the mahāyāna (大乘起信論),” and seeks to awaken the faith of all sentient beings in enlightenment and salvation by realizing the true nature of their mind and its role. That is, understanding and cultivating the human mind serves as the “great vehicle” that leads to the ultimate goal of Buddhism. The mind of the sentient being referred to in the Awakening of Faith is not restricted to the individual mind that we ordinarily assume ourselves to have, as noted below:

“是心則攝一切世間法出世間法” (T.1666: 32.575c21–22).“This mind [=the mind of the sentient being] thus includes all mundane and supramundane dharmas.”

This mind transcends the ordinary one and encompasses everything that we usually think of as existing independently of the mind: All phenomena are projections or productions of the mind. Moreover, the true nature of the mind is transcendental, which is the enlightened and pure state of it. After all, the Awakening of Faith is concerned with these two aspects of “the one mind (一心)” and the way to harmonize these two seemingly contradictory states—i.e., illusion and enlightenment. These two aspects are called the “production-and-cessation (生滅)” and the “true-thusness (眞如)” aspects of the mind, respectively. While the former characterizes the continuously arising and ceasing deluded metal states of the ordinary being, the latter refers to the original, not deluded, permanent essence of the mind, which is also called the “true mind (眞心),” “original enlightenment (本覺),” or “Buddha-nature (佛性).” For convenience, this paper refers to the mind of production-and-cessation as “the phenomenal mind”, and the mind of true-thusness as “the essential mind.”7

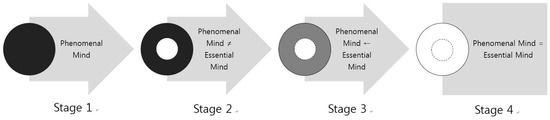

From the aforementioned perspective, the phenomenal mind stands in stark contrast or opposition to the essential mind. This would become problematic if unifying or harmonizing the two opposites was an important and urgent issue in the discourse. The mind that we, as ordinary beings, experience and conceive of is the phenomenal mind, which is filled with afflictions and delusions. In the discourse, however, it is asserted that we possess both this phenomenal mind which causes suffering, and the essential mind which leads to perfect bliss or nirvana. This prompts us to ask how the relationship between these seemingly contradictory minds can be explained properly; Figure 1 provides an outline of a process by which such an explanation could be given. The first stage of this process (Stage 1) explains the ordinary mental experience of sentient beings as a starting point for the discourse. Stage 2 confronts this phenomenal mind with the essential mind, while Stage 3 attempts to reconcile the phenomenal and essential minds by deriving the former from the latter. In the final stage (Stage 4), it is revealed that the phenomenal mind is ultimately not different from the essential mind. In view of the complex structure of these relations, it is anticipated that metaphor will play a significant role, not just in representing entities or states of affairs, but also in argumentation and persuasion.

Figure 1.

A process showing the stages for the explanation of the relationship between the phenomenal mind and the essential mind.

4. Embodied Correlation Metaphors for the Two Minds

This section discusses Stages 1 and 2 in Figure 1 with reference to metaphor, while Stages 3 and 4 are dealt with in Section 5. The first two stages are concerned with the two distinct and contrasting minds, each of which has its own metaphors; these are mainly correlation-based primary metaphors (and their related complex metaphors), whereas those in the following stages are predominantly resemblance-based, analogical metaphors.

As the starting point in the Awakening of Faith discourse, the phenomenal mind is revealed and characterized by the emergence of the essential mind. The overall strategy is to reveal how false our ordinary phenomenal mind is and how true our hidden essential mind is; as such, we would live our entire lives considering the phenomenal mind as the only and real mind and be motivated by it, were it not for the essential mind. However, ordinary experience generally finds the thing or state we call the essential mind inaccessible. In the discourse, the essential mind is also said to transcend the limits of our language and thought; indeed, Wŏnhyo speaks of “going away from language and cutting off thought (離言絶慮)” (T.1844: 44.207a02–03). As such, it initially seems absurd to take an imperceptible, unknowable, and thus ineffable entity like the essential mind as the target domain of metaphors. Generally, if something cannot be humanly experienced, then it cannot be verbalized, either literally or metaphorically, without being condemned as metaphysical or mystical. Of course, there are metaphorically expressible phenomena that are humanly experienced, but remain difficult or impossible to express, such as the subjective qualities of sensation and emotion. Nonetheless, for the purpose of this study, I admit the position of (the authors of) the discourse (like other Mahāyāna Buddhist texts) that the ultimate reality, like the essential mind, can be experienced by enlightened beings (Buddhas and bodhisattvas); it is from the perspective of these individuals that the discourse is presented in order to encourage all unenlightened, sentient beings to have faith in enlightenment and seek it accordingly.

4.1. Primary Metaphors for the Essential vs. Phenomenal Mind

Initially, the essential mind as experienced by enlightened beings has no verbal labels; thus, in order to communicate their ineffable experience to ordinary sentient beings, they need to give names to the essential mind. Consequently, most of the designations and descriptions are inevitably figurative.

Table 1 provides some metaphorical or figurative terms used for the essential mind in the discourse. Here, the essential mind is characterized metaphorically by: something that is genuine, not fabricated, and not fictional (“眞如”); a destination that should be reached (“實際”); the state of being awake (“本覺”); by what is hidden from oneself (“如來藏”); and even metonymically by what the Buddha has (“佛性”). Through such figurative naming and characterizations, the processes of conceptualizing the unknown essential mind can be undertaken, although vaguely, without recourse to phenomenological experience. Primary metaphors, in the sense of CMT, play a significant role in these processes.

Table 1.

Some figurative terms for the essential mind.

In recent discussions of CMT (e.g., Dancygier and Sweetser 2014; Gibbs 2017; Hampe 2017; Lakoff and Johnson 1999), it is customary to distinguish between two types of conceptual metaphor—“primary (or primitive) metaphor” and “complex (or compound) metaphor”—according to the proposal of Grady (Grady et al. 1996; Grady 1997a, 1997b, 1999). In Grady’s primary metaphor theory, primary metaphors are component basic metaphors into which a complex metaphor is decomposable. For instance, a conventional conceptual metaphor, such as THEORIES ARE BUILDINGS (motivating expressions such as “the foundation of his theory”), is analyzed as a complex metaphor composed of separate primary metaphors like CAUSAL/LOGICAL STRUCTURE IS PHYSICAL STRUCTURE and VIABILITY/FUNCTIONALTY IS ERECTNESS (Grady 1997b; Grady and Ascoli 2017). Primary metaphors are fundamental metaphoric mappings that have direct experiential correlation between source and target concepts. Although there hardly seems to be any plausible experiential correlation between theories and buildings in the complex metaphor THEORIES ARE BUILDINGS, Grady maintains that “continuing viability is associated with verticality in many instances in our environment” (Grady 1997b, p. 287). As “deeply entrenched associations” (Grady and Ascoli 2017, p. 27), primary metaphors are based on recurring experiential correlations between sensorimotor activity and subjective response. For instance, temperature and affect (AFFECTION IS WARMTH), height and quantity (MORE IS UP), as well as heaviness and difficulty (DIFFICULT IS HEAVY), have strong cognitive associations in certain types of experience called “primary scenes”, which are “minimal (temporally-delimited) episodes of subjective experience” (Grady 1997a, p. 24).

Based on this view, primary metaphors for the essential mind are metaphoric patterns that are not easily accounted for in terms of analogy or shared features between the source and target. For example, while the essential mind is often characterized as “clean/pure (淸淨)” and “quiet (寂靜)”; the target experience, i.e., the essential mind, as experienced by enlightened beings and still unknown to ordinary beings, and the source experience, e.g., clean water, a state of quiet, are not perceived as similar experiences. According to the primary metaphor theory, we associate the source concept with the target concept through recurring experience, and consequently speak through primary metaphors like GOOD/MORAL IS CLEAN and MENTAL TRANQUILITY IS PHYSICALLY QUIET.

Table 2 lists such primary-metaphor characterizations of the essential mind in the discourse. Among the proposed primary metaphors, some (e.g., IMPORTANCE IS SIZE, GOOD/MORAL IS CLEAN, and UNEMOTIONAL IS COOL) have already been discussed in the literature (e.g., Grady 1997b; Lakoff and Johnson 1999; Yu 2015; Yu et al. 2017), while others have yet to be referred to explicitly, such as those in the list provided by Lakoff and Johnson (1999, pp. 50–54), for example. However, while they need further empirical scrutiny, the latter primary metaphors may be plausible, since the stipulated concepts in a primary metaphor are more likely to be paired in experience and language.

Table 2.

Primary metaphors for the essential mind.

For instance, if something is found as original, substantial, genuine, or authentic, it is generally conceived of as reliable or trustworthy. When we witness what is perceivably great, wide, or deep, we usually feel its magnificence, and can easily couple this with the feeling of importance, limitlessness, or profundity. Meanwhile, that which is audibly quiet is usually associated with mental serenity and tranquility; what is perceptually constant is felt to be reliable; and that which radiates light is paired with enlightenment.

The suggested metaphoric patterns are assumed to be motivated by such strong experiential associations that the two linked facts become “inseparable counterparts, two sides of the same coin” (Grady 2005, p. 1601). These are not simply based on a causal or a generic-specific relationship, but on “our cognitive responses to sensory input” (Grady 1999, p. 96). Thus, the essential mind is metaphorically conceptualized as trustworthy, important, unlimited, profound, good, serene, reliable, enlightened, and aware by associating the perceptual “image content” with the non-perceptual “response content” (Grady 2005, p. 1606) in a primary metaphor. Typical examples of correlation-based metaphoric attributes or predicates for the essential mind found in the discourse are shown below:

- “眞心 true mind”; “大心 great mind”; “深心 deep mind”; “淨心 clean mind”; “靜心 quiet mind”; “常心 constant mind”

- “諸佛如來離於見想, 無所不遍, 心眞實” (T.1666: 32.581b23–24).“The Buddha-tathāgatas are free from all perverse views and thoughts, there are no corners into which their comprehension does not penetrate. Their mind is true and real.”

- “無明迷故, 謂心爲念, 心實不動” (T.1666: 32.579c23–24).“People, because of their ignorance, assume the mind to be deluded thoughts, but the mind in fact is motionless.”

- “眞如自體相者[…]常恒[…], 有大智慧光明[…], 遍照法界[…], 自性淸淨心[…], 常樂我淨[…], 淸涼不變自在” (T.1666: 32.579a12–17).“The essence and attributes of the true-thusness […] are constant and eternal, […] it is endowed with the light of great wisdom, […] the qualities of illuminating the entire universe, […] of mind pure in its self-nature; […] of eternity, bliss, self, and purity; […] of refreshing coolness, immutability, and freedom.”

In contrast, the phenomenal mind, which appears normal to ordinary beings until the essential mind emerges, is characterized as abnormal. That is, according to the covarying scalar properties of the two concepts in a primary metaphor, the phenomenal mind is conceptualized by the metaphoric pairing of negative concepts in relation to the primary metaphors for the essential mind listed in Table 2. The characterization of the phenomenal mind as opposing the essential mind is illustrated by the examples below:

- “妄心 untrue/delusive mind,” “妄想心 mind with untrue/delusive thoughts”

- “狹劣之心narrow and limited mind”

- “染心 defiled mind”

- “動心 moving/agitated mind”

- “生滅心 arising and ceasing mind,” “無常之心 impermanent mind”

- “無明心 not-illuminated/ignorant mind”

- “不覺心 unawakened/unenlightened mind”

In the discourse, the phenomenal mind is described as something so delusive that it should be abandoned, so narrow and impeded as to be an obstruction (障礙) to the mastery of virtues, and as contaminated (有漏) by ignorance (無明) and affliction (煩惱). However, these unenlightened, disquieted, and ever-changing aspects are not considered intrinsic to the nature of the ordinary mind, but as extrinsic, unintended, or temporary defilements (塵) from without. This dimension of the mind is discussed in Section 5, which focuses on the relationship between the two minds.

4.2. Complex and Analogical Metaphors for the Essential Mind

This subsection examines more specific or complex metaphors for the essential mind in terms of primary metaphor theory. The discourse often explicitly introduces metaphors to explain the nature and function of the essential mind. Some of the most conspicuous metaphors can be listed as conceptual patterns, as seen below:

- THE ESSENTIAL MIND IS EMPTY SPACE

- THE ESSENTIAL MIND IS BRIGHT LIGHT

- THE ESSENTIAL MIND IS A CLEAR MIRROR

The source concept of THE ESSENTIAL MIND IS EMPTY SPACE is expressed as the “sky (太虛)” or the “empty void (虛空).” It is worth noting that the concept includes most of the sources of the primary metaphors listed in Table 2: The sky is empty, great, wide, clear, pure, quiet, unmoving, and unchangeable (when there are no clouds). In this sense, the metaphor of EMPTY SPACE can be regarded as a complex metaphor composed of primary metaphors, although, as shown in Section 5, it can also be used as an analogical metaphor according to the context.

THE ESSENTIAL MIND IS BRIGHT LIGHT is another complex metaphor that can be understood as the combination of ENLIGHTENED IS VISUALLY ILLUMINATED, GOOD/MORAL IS CLEAN, and GOOD/MORAL IS BRIGHT. The first primary metaphor is closely associated with KNOWING IS SEEING, and more specifically with INTELLIGENCE IS A LIGHT SOURCE, wherein understanding or realizing the reality is conceptualized as seeing things clearly in bright light. These metaphors are expressed in the discourse by phrases such as “enlightening illumination (覺照),” “the light of great wisdom (大智慧光明)” or “the light of wisdom (慧光明),” which refer to the nature of the essential mind as not giving rise to the deluded thoughts caused by “ignorance (無明),” literally, “no light” (T.1666: 32.579a26–29). The primary metaphor GOOD/MORAL IS CLEAN is easily connected with GOOD/MORAL IS BRIGHT given the frequent correlation between the brightness of colors and the cleanliness of things; for example, a clean sheet of white paper is brighter than one contaminated with dust.

THE ESSENTIAL MIND IS A CLEAR MIRROR can be also interpreted as a complex metaphor. The MIND-AS-MIRROR metaphor is actively used in the discourse, as some introductory phrases show: “the characteristics of the essence of enlightenment […] are analogous to those of a clear mirror (覺體相者[…]猶如淨鏡)” (T.1666: 32.576c20–21), and “the mind of the sentient being is like a mirror (衆生心者, 猶如於鏡)” (T.1666: 32.581c03–14). A clean mirror is clear and shines brightly in the light; as such, the properties evoked by the source concept of mirror include cleanness, clearness, and brightness. These properties prompt correlated target concepts such as goodness/morality, and knowledge/wisdom. Of course, mirrors have more properties, and these can easily be used in the creation of analogical metaphors, as Section 5 shows.

What does it mean that the essential mind is characterized by primary and complex metaphors as well as analogical metaphors? If we tentatively define an analogical metaphor as a metaphor of which source and target domains are perceived to resemble each other in some respects, we see that enlightened beings perceive that there is something in common between the essential mind and things, such as empty space, sky, bright light, or a clean mirror. Of course, the metaphoric mapping in an analogical metaphor is not simply the mapping of perceived mental images, like color or shape, which gives rise to an “image metaphor,” as exemplified by “my wife’s waist is an hourglass” (Lakoff and Turner 1989, p. 90). The perception of shared features between the source and target is principally based on analogical reasoning that involves (more abstract) image schemas and event structures, and which allows for limited or extended mappings or alignments depending on discursive purposes. Before dealing with this dimension in Section 5, it is worth noting how the three specific metaphors mentioned above are interconnected with respect to image schemas.

Introduced by Mark Johnson (Johnson 1987) and George Lakoff (Lakoff 1987), the notion of image schema has played a crucial role in explaining the bodily grounding of abstract conceptualization and reasoning in cognitive linguistics. Image schemas are “the recurring patterns of our sensory-motor experience by means of which we can make sense of that experience and reason about it” (Johnson 2005, pp. 18–19). Structuring the source domains in embodied conceptual metaphors, image schemas can also be appropriated for the metaphoric mapping of embodied source domains onto abstract target domains such as the mind. Seen from the perspective of image schemas, the source domains of the metaphors for the essential mind mentioned above share the opposite image schema of CONTAINMENT, upon which a representative metaphor for the ordinary phenomenal mind (i.e., MIND-AS-CONTAINER metaphor) is based. The CONTAINMENT or CONTAINER image schema consists of a boundary distinguishing an interior from an exterior (Lakoff 1987, p. 271). In ordinary experience, our mind is a bounded, limited container where ideas, thoughts, and emotions are produced, received, manipulated, released, or stored like objects. In contrast, source images like empty space, sky, and radiant light exhibit a common spatial structure (NON-CONTAINER) characterized by the notions of unboundedness, limitlessness, endlessness, or infiniteness. The sky’s vast space is unbounded, light rays radiate in all directions infinitely, and the range of things that can be reflected in the mirror are limitless. The ocean is another example of an unbounded non-container vast and unfathomable to human eyes. Thus, although the religiously or mystically experienced infiniteness of the essential mind is invisible, inconceivable, and ineffable, the essential mind is made metaphorically “visible” and “speakable” through analogies found in the mundane world of our ordinary experience.

5. Discursive Analogical Metaphors for the Oneness of the Two Minds

As seen in the previous section, the discourse presents the essential mind in opposition to the phenomenal mind—an opposition metaphorically characterized by binary pairs: true and false, big and small, deep and shallow, clean and dirty, bright and dark, empty and filled, permanent and changing, still and moving, cool and hot, and so on. The chief concern of the Awakening of Faith is to reconcile the two incompatible minds and thereby achieve perfect enlightenment. The encounter of ordinary beings with the essential mind is not akin to being granted something from without or being saved by grace. The basic assumption of the discourse is that all sentient beings have the potential to attain enlightenment because the ordinary mind is inherently or originally enlightened. That is, the phenomenal and the essential mind are not separated or distinct from each other, but are closely interrelated. Herein lies the conundrum: Why are sentient beings misled by delusion and ignorance from the beginning despite having an inherently enlightened mind? As such, the key challenge of the Awakening of Faith is to unify the apparent opposites in explaining the mind. This section shows how the gap between inherent enlightenment and the actual deluded mind is bridged metaphorically.

5.1. The Essential Mind Is Hidden in the Phenomenal Mind

The first strategy for unifying the two opposite minds is to show that they are not isolated from each other, but located in the same place and even overlap each other. More specifically, the essential mind is part of or hidden in the phenomenal mind. In this respect, the essential mind is something that can be found if actively sought, like the origin or source from which something springs or to which one must return.

The relationship between the two minds is often conceptualized by metaphors such as storage, a spring or fountainhead, the corpus or main part of body, and innateness. Thus, the essential mind—a term that is metaphorical itself—is: “the place storing a buddha (如來藏),” “the fountainhead of the mind (心源),” “the corpus of the mind (心體),” or “the innate nature of the mind (心性).” In other words, the essential mind is something that is hidden and needs to be revealed, the source from which one goes astray, or the main body or essence of something. Thus, this aspect of the essential mind is also reflected in the expression “original enlightenment (本覺),” which refers to the original enlightened and genuine mind or the inherent purity of the mind. The notion of original/inherent enlightenment necessarily entails the existence of non-enlightenment (不覺), which needs to be removed or reverted to the original mind through a process known as “actualizing enlightenment (始覺).”

Seen from the perspective of primary metaphor theory, we can assume that the abovementioned metaphors for the essential mind are based on the experiential correlation in concepts, such as KNOWING IS SEEING, IGNORANCE IS NOT SEEING A HIDDEN THING/THE SOURCE/THE FOUNDATION, and VALUED IS HIDDEN. Metaphorically speaking, the ordinary phenomenal mind of sentient beings is in a state of not seeing the reality of what is already enshrined in the mind. Indeed, enlightenment in Buddhism is often conceptualized by the metaphor of seeing, and the Awakening of Faith also speaks of “(to be able to) see the nature of the mind ([得]見心性)” (T.1666: 32.576b25).

As such, the question of why the hidden and valued essential mind is invisible to sentient beings is answered metaphorically by the imagery of the lack of light (無明), the darkness (闇) caused by it, sleep (眠), and dreaming (夢). That is, the reason for the invisibility of what ought to be seen is that one is in a dark place, sleeping, or dreaming. A representative term for all these situations is “non-enlightenment (不覺),” which literally means “being not awake.”

A question emerges at this stage of the argument: if the Buddha-nature, which is pure in self-nature, is within our mind, then why is it invisible to us? Why is our ordinary mind experienced as the phenomenal mind; that is, why are we unenlightened? In Buddhism, the cause of this non-enlightenment is commonly referred to as, somewhat tautologically, “ignorance (無明),” which literally means the “lack of light.” The question is, after all, about why we are ignorant.

5.2. The Phenomenal Mind Emerges from the Essential Mind Through Ignorance

Having followed the argumentation presented by the discourse, we need to consider the specific process that makes ordinary beings unable to realize that they possess the essential mind, that is, the Buddha-nature, which is the potentiality of enlightenment. We are essentially faced with the question of why sentient beings are unenlightened and overwhelmed by suffering from the outset. The common metaphorical answer to this question is that the phenomenal state of mind is contaminated (“defiled mind [染心]”) or moving (“moving mind [動心]”),8 thereby rendering the essential mind within it invisible. Here, the discourse notes the following, as provided below:

“是心從本已來, 自性淸淨, 而有無明. 爲無明所染有其染心” (T.1666: 32.577c02–04).“The mind, though pure in its self-nature from the beginning, is accompanied by ignorance. Being defiled by ignorance, a defiled mind comes into being.”“一心體有本覺, 而隨無明動作生滅. 故於此門, 如來之性隱而不顯, 名如來藏” (T.1844: 44.206c18–20).“The essence of the one mind, though originally enlightened, is accompanied by ignorance and activates production and cessation. Therefore, in this state of mind the buddha-nature is hidden and not visible so that it is called the place storing a buddha.”

That the essential mind is made (metaphorically) invisible by the (metaphorical) pollution and motion of the phenomenal mind leads us to reconsider the relationship between the two. This prompts another fundamental question: Where does the phenomenal mind come from, given the presence of the essential mind?

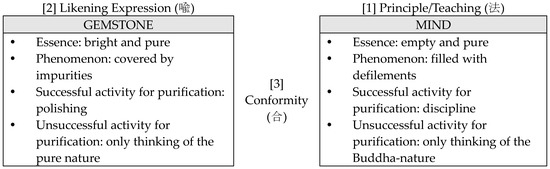

This question regarding the causes and conditions of the phenomenal mind centers on the existence of ignorance and its role in the creation of the deluded mind. According to the discourse, the phenomenal mind—polluted and constantly moving, appearing and disappearing, and thus becoming afflicted—is produced by the defilement or agitation of the essential mind through ignorance (無明). This situation gives rise to specific analogical metaphors for the relationship between the essential mind, ignorance, and the phenomenal mind. With respect to defilement, for instance, we find a gem and a mirror metaphor, as shown below:

“譬如大摩尼寶, 體性明淨, 而有礦穢之垢. 若人雖念寶性, 不以方便種種磨治, 終無得淨. 如是衆生眞如之法體性空淨, 而有無量煩惱染垢. 若人雖念眞如, 不以方便種種熏修, 亦無得淨” (T.1666: 32.580c12–16).“It is like a precious gemstone, which is bright and pure in its essence but is covered by impurities. Even if one thinks of the gemstone’s precious nature, unless he polishes it in various ways, he will never be able to purify it. Like this, the mind of sentient beings is empty and pure in its essential nature, but is filled with immeasurable impure defilements. Even if one thinks of the true-thusness of the mind, unless his mind is disciplined in various ways, it cannot become pure.”“衆生心者, 猶如於鏡. 鏡若有垢, 色像不現. 如是衆生心若有垢, 法身不現” (T.1666: 32.581c04–05).“The mind of the sentient being is like a mirror. Just as a mirror cannot reflect images if it is coated with dirt, so the true Buddha-nature cannot appear in the mind of the sentient being if it is coated with the dirt of defilements.”

These examples also show the typical structure of the analogical figuration prevalent in Buddhist discourse. In this form of discursive presentation, a certain complex referent—a “principle or teaching (法)”—is consciously likened to something simple and familiar, known as a “likening expression (喩)”, through the explicit use of connecting words that roughly mean “is like” (such as “譬如,” “猶如,” “如,” and “等”). Such a simile is usually followed by statements regarding its aptness (called “conformity [合]”). This structure shown by the first example is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

A typical structure of analogical figuration in the form of principle, likening expression, and conformity.

What then is the phenomenal mind in this metaphorical understanding of the mind as a gemstone or a mirror? If the essential mind is like the pure nature of a gemstone, the phenomenal mind is like the gemstone with impurities. If the essential mind is like a clear mirror, the phenomenal mind is like the mirror covered with dust or dirt. When seen from this perspective, the phenomenal mind is understood as the essential mind but stained and polluted. Nonetheless, the argument that the phenomenal mind emerges from the essential mind when it is defiled still faces the problem of where such defilement comes from. How do the impurities (defilements or afflictions) interact with the essential mind to give rise to the phenomenal mind? How can they be removed?

For ease of discussion, let us focus on the mirror metaphor, which has been of great importance in East Asian Mahāyāna Buddhism (Demiéville 1987; Wayman 1974). The analogical metaphor THE MIND IS A MIRROR is particularly apt for describing the true nature of the mind in Buddhism. The Awakening of Faith also uses the mirror metaphor to explain the originally enlightened nature of the mind (T.1666: 32.576c20–29). Just as a mirror reflects all phenomena without discriminating between them, the enlightened mind reflects all that it sees without comment or judgement. Just as what appears in a mirror is not the actual thing and empty, all things arising in the mind are empty and insubstantial. Just as a mirror is not stained by a reflection in it, the true mind is not contaminated by mental defilements. Indeed, there is nothing more to cling to in the enlightened mind than the reflections in a mirror.

The dust (塵) on the mirror, denoting metaphorical mental defilements or afflictions (煩惱), is also not intrinsic to the mirror, but comes from without. As such, the defilements are often referred to as “defilements as the dust coming like guests (客塵煩惱).” However, if one wants to keep the mirror of the mind clear and pure, then one must constantly make the effort to purify it. Regarding defilements as something to be removed gives them an objective reality by exteriorizing them. In this way, substantiality is imputed to these impurities, despite their empty and illusory in nature. Thus, the dualistic oppositions of purity and impurity, of the essential and the phenomenal mind, of enlightenment and non-enlightenment, remain unresolved. Where the metaphor of the clear and bright mirror is apt for conceptualizing the essential mind, which is pure and enlightened, the metaphor of the stained mirror is ill-suited to explaining the non-dualistic relationship between the essential mind and the phenomenal mind. In order to remain true to the purpose of the Awakening of Faith, the introduction of new and suitable metaphors that capture the real characteristics of things is required.

5.3. The Phenomenal Mind Is Ultimately Not Different from the Essential Mind

One of the principal tenets of the Awakening of Faith can be summarized as the principle of non-dualistic oneness or, more accurately, the principle of “being neither identical nor different (非一非異)”; in this context, Wŏnhyo often uses the expression “無二” or “不二,” which literally means “not-two.” Rooted in the Buddhist fundamental teaching of the “middle way (中道),” which avoids two extremes, this principle lets us assume that the phenomenal mind is ultimately identical to the essential mind, despite the former appearing conventionally different from the latter. This subsection examines how this argument works through metaphors.

As mentioned earlier, the mind of the sentient being is either approached from the perspective of true-thusness (i.e., the essential mind) or from that of production-and-cessation (i.e., the phenomenal mind). Although the one mind consists of these two aspects, each approach practically considers both aspects together. While the essential mind is a common quality encompassing all mental phenomena, the myriad aspects of the phenomenal mind arising from causes and conditions have the true nature of the essential mind in common. This relationship is analogically likened to that between earthenware (瓦器) and clay (微塵). Just as the generic property “clayness” subsumes all pieces of earthenware, the generic property of the essential mind embraces all phenomena of the phenomenal mind (T.1845: 44.227b16–23). In other words, just as pieces of various kinds of earthenware are of the same nature because they are made of clay, the various manifestations of both enlightenment and non-enlightenment (the phenomenal mind) are of the same true-thusness nature of the essential mind (T.1666: 32.577a23–25).

Other metaphors are similarly helpful in asserting that the seeming opposition between the essential mind, which is true and unmoving, and the phenomenal mind, in which illusory thoughts (妄念) are arising and ceasing, is not real. These include the metaphor of a flower in the sky (空華)—a familiar metaphor for illusory things in Buddhist texts. Just as a person with an eye disease sees flowerlike floating spots in the sky that do not exist in reality, a sentient being suffering from ignorance sees something illusory, i.e., afflictions in the phenomenal mind, as real. Just as one who has recovered from an eye disease no longer sees illusory flowers, an enlightened being sees emptiness in the illusory phenomenal mind; that is, he sees the essential mind and the phenomenal mind as the same (T.1844: 44.207b09–10).

This fundamental non-dualistic nature (非異) of the mind is asserted in the discourse in such a way that the essential aspect of enlightenment is merged harmoniously (和合) with the phenomenal aspect of non-enlightenment (ignorance and defilements). That is, the phenomenal mind is fundamentally not different from the essential mind in that the former is actually the moving (arising and ceasing) aspect of the latter under certain conditions, and that there exists no separate essence of the phenomenal mind apart from the essence of the essential mind. However, there is also the dimension of nonidentity (非一) between the essential and the phenomenal minds. If the phenomenal mind were in fact identical to the essential mind, then whenever the phenomenal mind became extinct so too would the essential mind. According to the argument of the discourse, however, the mind never loses the nature of true-thusness, even if the arising-and-ceasing mind disappears. In order to cope with these complex and dynamic characteristics of the mind (i.e., being neither identical nor different), the Awakening of Faith introduces what is probably its most prominent analogical metaphor of the ocean and wave, as shown by the phrases below:

“如大海水因風波動. 水相風相不相捨離. 而水非動性. 若風止滅, 動相則滅. 濕性不壞故” (T.1666: 32.576c11–13).“It is like the ocean’s water and its waves caused by the wind. The moving water and the moving wind are inseparable from one another. But the water is not mobile by nature. If the wind ceased, the movement of the water also ceases. But the wetness of the water remains undestroyed.”

The ocean metaphor for the mind is not unfamiliar in Buddhism, in that common images of the ocean’s vastness and deepness are suitably related to the attributes of the enlightened mind or true reality. However, the features evoked by the phrases above and the comments in the discourse are somewhat specific and give rise to a cluster of metaphors, such as THE MIND IS AN OCEAN, IGNORANCE IS WIND, THE PHENOMENAL MIND IS WAVES, and THE ESSENTIAL MIND IS THE WATER OF THE OCEAN. The analogical metaphoric mapping from the source domain (the ocean with its waves) to the target domain (the mind to be explained in the discourse) is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Selected analogical mapping from OCEAN to MIND.

One of the most salient and easily perceived features of the ocean is the waves that occur on its surface. Waves are produced by the wind meeting the water and moving. However, the causal nature of moving is intrinsic to the wind, not to the water of the ocean, which only has the nature of wetness despite it moving along with the wind. Thus, if the wind ceases, so do the waves. However, it is only the kinetic nature of the waves that ceases—the wet nature of the water continues. Just like the ocean in these respects, the mind has a “wave-like” phenomenal aspect and a “water-like” essential aspect. Although the mind has an essential aspect called the true-thusness mind or enlightened pure mind, if the wind of ignorance (“無明風”) blows, the ocean of the mind (“心海”) is moved to produce the wave-like phenomenal mind (“the waves of the seven consciousnesses [the seven levels of the deluded mind] [七識波浪]”). However, because ignorance is not intrinsic to the mind, if the ignorance moving the mind ceases, then the moving mind annuls its streaming activity without losing its originally unmoving and enlightened nature.

From this metaphoric analogical reasoning, we can conclude that the essential mind (which is originally pure and tranquil) is fundamentally not different from the phenomenal mind (which appears true, but which does not have its own substantial nature). The phenomenal mind appears true and real, just as waves appear as discrete and substantial forms to the sentient being. However, the phenomenal mind does not actually exist, and it is like an illusion or dream, because the sentient being’s mind has cognitive and afflictive obstructions resulting from ignorance and attachment. An ignorant mind constructs a perceiving subject and its perceived objects, sees as real what are actually imaginary external phenomena, discriminates between the pleasant and the unpleasant, and is attached to the impermanent. By relying on these false imaginings, sentient beings subject themselves to continued suffering. The enlightened and pure mind is free from discriminating thoughts and mental afflictions, and thus sees the ultimate nature of reality as unitary, just as the ocean is perceived as an undifferentiated mass of water.

The metaphor of the ocean and the waves illuminates that the treatment of the problem of afflictions proceeds differently from the mirror metaphor mentioned earlier. While the latter depicts mental afflictions as something substantial to be removed, like dust from a mirror, the former represents afflictions as something illusory, as waves shaped by external conditions, and insubstantial but for the watery nature of the ocean. In this line of reasoning, the fundamental promise of Mahāyāna Buddhism that the sentient being (or the ordinary mind) is the buddha (the enlightened being) can be maintained.

However, in order for boddhisattvas (beings who have resolved to become a Buddha) to attain Buddhahood, they must develop and practice virtues or qualities such as giving, morality, patience, meditation, and wisdom. In the Awakening of Faith, Buddhist practices for gaining insight into the true nature of mind and bringing an end to suffering are also discussed in metaphors. While an examination of these metaphors is beyond the scope of this paper, one point is worth mentioning: According to discursive purposes, the same metaphor can be used to highlight different aspects, or new suitable metaphors can be introduced. For instance, the same ocean metaphor is used to refer to the situations of ordinary beings whose scope is vast like an ocean and whose lives are perilous as if in the wavy ocean (“the ocean of birth and death [生死之海]”). Here, Buddhist practice is like a voyage to the safe shore (“the other shore of nirvana [涅槃之岸]”). In addition to commonly used journey metaphors, achieving enlightenment is an arduous and taxing process that is likened to perfuming (“薰習”), in which the deluded phenomenal mind is permeated by the essential mind just as clothes are gradually permeated with the scent of incense, or to agriculture, in which a wholesome root (“善根”) is cultivated into a tree.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, I have demonstrated how discourse about the human mind in Mahāyāna Buddhism resorts to cognitive and discursive metaphors. I have analyzed the Treatise on the Awakening of Faith According to the Mahāyāna and its two commentaries by Wŏnhyo, using these texts as representative of the Mahāyāna Buddhist discourse on the mind. Starting from the argument of the Awakening of Faith that our mind has two aspects, i.e., the ordinary mundane mind (called “the phenomenal mind”) and the transcendental supramundane mind (called “the essential mind”), this study focused on exploring the relationship between the two minds articulated through metaphoric language. First, I examined how the essential mind, which is said to transcend verbal expression, is made “speakable” through the use of metaphor. Here, it was emphasized that even if the essential mind is only known to enlightened beings (or is experienced by a few practitioners seeking to attain enlightenment through meditation), its recourse to metaphorical description is inevitable for teaching the dharma. The analysis of such metaphors for the essential mind was placed in the context of primary metaphor theory, which emphasizes the experiential correlation between source and target concepts. It was found that the essential mind, which is said to be beyond sensory world, is described in sensory terms, so that metaphoric conceptualizations of the unexperienced essential mind emerge by associating perceptual image contents with non-perceptual response contents.

I also showed that the phenomenal mind is characterized as opposing the essential mind through primary metaphors. In addition to primary metaphors, complex and analogical metaphors were also dealt with, not only with respect to the essential mind proper which is understood in terms of NON-CONTAINER (unboundedness) image schema, but also in the relationship between the two minds for which choosing a more appropriate or apt metaphor is important. Thus, this paper illustrated how such specific analogical metaphors and their interpretations are often introduced consciously into the discourse according to the discursive purpose.

This paper also revealed how the ocean-and-waves metaphor is more suitable than the mirror metaphor for uniting the two opposing minds harmoniously. Of course, I do not mean to suggest that the analogical metaphor of ocean should be the most suitable model for our mind in Mahāyāna Buddhism. There are, in fact, alternative metaphoric mind models available, such as empty space, mirror, light source, gem, and so on. Since metaphoric mapping is selective (see Lakoff and Johnson 1980; Dancygier and Sweetser 2014), any metaphor can play this role in highlighting certain aspects of the target concept, hiding others, and showing a different inferential structure. As we saw, while the clear mirror, which reflects and reveals what is before it, is a more apt metaphor for the essential mind with respect to the mind’s relation to the world, the ocean metaphor is better suited in that it resolves the problem of defilement more appropriately. It is also undeniable, however, that the ocean metaphor has the potential to become a representative model for the mind and reality, as it shows vastness, deepness, and reflectivity (though limited compared to mirror), the simultaneity of the essence (or the whole) and its phenomena (or parts), and all phenomena’s mutual intertwining without losing their individual identities (like waves causing mutually and interrelated, recognizably unique and discrete phenomena).

While this study focused on the metaphors in a certain, limited canonical discourse, it is desirable to further examine the culturally and historically changing metaphors for the Buddhist mind in various discourses including modern dharma talks (such as Silvestre-López and Navarro i Ferrando 2017), on metaphors for meditation practice in a modern Western context). One such examination could be on the question of why the sky-and-clouds metaphor, along with the ocean-and-waves metaphor, is preferred in Tibetan Buddhism (e.g., Kyabje Kalu Rinpoche 1997). It is also worth investigating how the predominance of impersonal metaphors, like sky and ocean, in Buddhism is compensated by personification metaphors. By providing a perspective from Buddhism, this paper contributes to the emerging and ongoing cognitive-discursive research on “metaphor in religion and spirituality” (Pihlaja 2017, p. 1), which explores how “relatively intersubjectively inaccessible experience” (Sweetser and DesCamp 2014, p. 11) is brought down to the human scale and made accessible by metaphor.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2010-361-A00013) and the Hankuk University of Foreign Studies Research Fund of 2018.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Austin, James H. 1998. Zen and the Brain: Toward an Understanding of Meditation and Consciousness. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barnden, John A. 1997. Consciousness and Common-Sense Metaphors of Mind. In Two Sciences of Mind: Readings in Cognitive Science and Consciousness. Edited by Seán Ó Nualláin, Paul Mc Kevitt and Eoghan Mac Aogáin. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 311–40. [Google Scholar]

- Boeve, Lieven, and Kurt Feyaerts, eds. 1999. Metaphor and God-Talk. Bern: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Buswell, Robert E. 2017. Wŏnhyo: Buddhist Commentator Par Excellence. Journal of Korean Religions 8: 131–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buswell, Robert E., and Donald S. Lopez. 2014. The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, Francisca. 2014. Buddhist Mind and Matter. Religions 5: 422–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciurtin, Eugen. 2013. Karma Accounts: Supplementary Thoughts on Theravāda, Madhyamaka, Theosophy, and Protestant Buddhism. Religion 43: 487–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coseru, Christian. 2012. Perceiving Reality: Consciousness, Intentionality, and Cognition in Buddhist Philosophy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Covill, Linda. 2009. A Metaphorical Study of Saundarananda. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Pub. [Google Scholar]

- Dancygier, Barbara, and Eve Sweetser. 2014. Figurative Language. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Demiéville, Paul. 1987. The Mirror of the Mind. In Sudden and Gradual: Approaches to Enlightenment in Chinese Thought. Edited by Peter N. Gregory. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, pp. 13–40. [Google Scholar]

- DesCamp, Mary Therese, and Eve Sweetser. 2005. Metaphors for God: Why and How Do Our Choices Matter for Humans? The Application of Contemporary Cognitive Linguistics Research to the Debate on God and Metaphor. Pastoral Psychology 53: 207–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dille, Sarah J. 2004. Mixing Metaphors. New York: T&T Clark International. [Google Scholar]

- Draaisma, Douwe. 2000. Metaphors of Memory: A History of Ideas About the Mind. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Feyaerts, Kurt, ed. 2003. The Bible through Metaphor and Translation: A Cognitive Semantic Perspective. Oxford: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Xiuping, and Chun Lan. 2018. Buddhist Metaphors in the Diamond Sutra and the Heart Sutra. In Religion, Language, and the Human Mind. Edited by Paul Chilton and Monika Kopytowska. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 229–62. [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner, David. 2008. Metaphor and Mandala in Shingon Buddhist Theology. Sophia 47: 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garfield, Jay L. 2015. Engaging Buddhism: Why It Matters to Philosophy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gentner, Dedre, and Jonathan Grudin. 1985. The Evolution of Mental Metaphors in Psychology: A 90-Year Retrospective. American Psychologist 40: 181–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, Raymond W. 2017. Metaphor Wars: Conceptual Metaphor in Human Life. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grady, Joseph E. 1997a. Foundations of Meaning: Primary Metaphors and Primary Scenes. Ph.D. dissertation, University of California at Berkeley, Berkeley, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Grady, Joseph E. 1997b. THEORIES ARE BUILDINGS revisited. Cognitive Linguistics 8: 267–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grady, Joseph E. 1999. A Typology of Motivation for Conceptual Metaphor: Correlation vs. Resemblance. In Metaphor in Cognitive Linguistics. Edited by Raymond W. Gibbs and Gerard J. Steen. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 79–100. [Google Scholar]

- Grady, Joseph E. 2005. Primary Metaphors as Inputs to Conceptual Integration. Journal of Pragmatics 37: 1595–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grady, Joseph E., and Giorgio A. Ascoli. 2017. Sources and Targets in Primary Metaphor Theory: Looking Back and Thinking Ahead. In Metaphor: Embodied Cognition and Discourse. Edited by Beate Hampe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 27–45. [Google Scholar]

- Grady, Joseph E., Sarah Taub, and Pamela Morgen. 1996. Primitive and Compound Metaphors. In Conceptual Structure, Discourse, and Language. Edited by Adele Goldberg. Stanford: CSLI, pp. 177–87. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory, Peter N. 1986. The Problem of Theodicy in the Awakening of Faith. Religious Studies 22: 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakeda, Yoshito S. 2006. The Awakening of Faith Attributed to Aśvaghosha. Translated by Yoshito S. Hakeda. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hampe, Beate, ed. 2017. Metaphor: Embodied Cognition and Discourse. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Howe, Bonnie. 2006. Because You Bear This Name: Conceptual Metaphor and the Moral Meaning of 1 Peter. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Howe, Bonnie, and Joel B. Green, eds. 2014. Cognitive Linguistic Explorations in Biblical Studies. Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, Soonil. 2006. Metaphor and Literalism in Buddhism: The Doctrinal History of Nirvana. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Mark. 1987. The Body in the Mind: The Bodily Basis of Meaning, Imagination, and Reason. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Mark. 2005. The Philosophical Significance of Image Schemas. In From Perception to Meaning: Image Schemas in Cognitive Linguistics. Edited by Beate Hampe. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 15–33. [Google Scholar]

- Kearns, Michael S. 1987. Metaphors of Mind in Fiction and Psychology. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky. [Google Scholar]

- Kövecses, Zoltán. 2015. Where Metaphors Come from: Reconsidering Context in Metaphor. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kragh, Ulrich Timme. 2010. Of Similes and Metaphors in Buddhist Philosophical Literature: Poetic Semblance through Mythic Allusion. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 73: 479–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyabje Kalu Rinpoche. 1997. Luminous Mind: The Way of the Buddha. Somerville: Wisdom. [Google Scholar]

- Lakoff, George. 1987. Women, Fire, and Dangerous Things: What Categories Reveal about the Mind. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lakoff, George. 1993. The Contemporary Theory of Metaphor. In Metaphor and Thought, 2nd ed. Edited by Andrew Ortony. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 202–51. [Google Scholar]

- Lakoff, George, and Mark Johnson. 1980. Metaphors We Live by. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lakoff, George, and Mark Johnson. 1999. Philosophy in the Flesh: The Embodied Mind and Its Challenge to Western Thought. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Lakoff, George, and Mark Johnson. 2003. Metaphors We Live by, 2nd ed. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lakoff, George, and Mark Turner. 1989. More than Cool Reason: A Field Guide to Poetic Metaphor. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lan, Chun. 2012. A Cognitive Perspective on the Metaphors in the Buddhist Sutra “Bao Ji Jing”. Metaphor and the Social World 2: 154–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leary, David E., ed. 1990. Metaphors in the History of Psychology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Louis Wei-lun, and Wen-yu Chiang. 2007. Emptiness we Live by: Metaphors and Paradoxes in Buddhism’s Heart Sutra. Metaphor and Symbol 22: 331–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masson, Robert. 2014. Without Metaphor, No Saving God: Theology after Cognitive Linguistics. Leuven: Peeters. [Google Scholar]

- McMahan, David L. 2002. Empty Vision: Metaphor and Visionary Imagery in Mahāyāna Buddhism. London: RoutledgeCurzon. [Google Scholar]

- Pasanek, Brad. 2015. Metaphors of Mind: An Eighteenth-Century Dictionary. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pihlaja, Stephen. 2017. Introduction: Special Issue on Metaphor in Religion and Spirituality. Metaphor and the Social World 7: 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinker, Steven. 2007. The Stuff of Thought: Language as a Window into Human Nature. London: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Rasskin-Gutman, Diego. 2009. Chess Metaphors: Artificial Intelligence and the Human Mind. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, Peter, and Miori Nagashima. 2018. Perceptions of Danger and Co-occurring Metaphors in Buddhist Dhamma Talks and Christian Sermons. Cognitive Linguistic Studies 5: 133–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlieter, Jens. 2013. Checking the Heavenly ‘Bank Account of Karma’: Cognitive Metaphors for Karma in Western Perception and Early Theravāda Buddhism. Religion 43: 463–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, Lawrence, ed. 2014. The Routledge Handbook of Embodied Cognition. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Silvestre-López, Antonio-José, and Ignasi Navarro i Ferrando. 2017. Metaphors in the Conceptualisation of Meditative Practices. Metaphor and the Social World 7: 26–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyer Yu, Dan. 2012. The Sentient Reflexivity of Buddha Nature: Metaphorizing Tathagatagarbha. The World Religious Cultures 6: 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg, Robert J. 1990. Metaphors of Mind: Conceptions of the Nature of Intelligence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sweetser, Eve. 1990. From Etymology to Pragmatics: Metaphorical and Cultural Aspects of Semantic Structure. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sweetser, Eve, and Mary Therese DesCamp. 2014. Motivating Biblical Metaphors for God: Refining the Cognitive Model. In Cognitive Linguistic Explorations in Biblical Studies. Edited by Bonnie Howe and Joel B. Green. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 7–23. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, Evan. 2015. Waking, Dreaming, Being: Self and Consciousness in Neuroscience, Meditation, and Philosophy. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Turbayne, Colin Murray. 1991. Metaphors for the Mind: The Creative Mind and Its Origins. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ŭn, Chŏnghŭi. 1991. Wŏnhyo Ŭi Taesŭng Kisillon So Pyŏlgi [Wŏnhyo’s Commentary and Separate Record on the Awakening of Faith]. Translated by Chŏnghŭi Ŭn. Seoul: Ilchisa. [Google Scholar]

- Valle, Ronald S., and Rolf Von Eckartsberg, eds. 1981. The Metaphors of Consciousness. New York: Plenum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Varela, Francisco J., Evan Thompson, and Eleanor Rosch. 1991. The Embodied Mind: Cognitive Science and Human Experience. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Varela, Francisco J., Evan Thompson, and Eleanor Rosch. 2016. The Embodied Mind: Cognitive Science and Human Experience, rev. ed. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, B. Allan. 2007. Contemplative Science: Where Buddhism and Neuroscience Converge. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wayman, Alex. 1974. The Mirror as a Pan-Buddihst Metaphor-Simile. History of Religions 13: 251–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, Claudia. 2002. Die Lichtmetaphorik im frühen Mahāyāna-Buddhismus. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Ning. 2015. Metaphorical Character of Moral Cognition: A Comparative and Decompositional Analysis. Metaphor and Symbol 30: 163–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Ning, Lu Yu, and Yue Christine Lee. 2017. Primary Metaphors: Importance as Size and Weight in a Comparative Perspective. Metaphor and Symbol 32: 231–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | According to a convention in cognitive linguistics, conceptual metaphors (and concepts) are indicated by capital letters to distinguish them from metaphorical expressions. In a conceptual metaphor in the form of CONCEPT A IS CONCEPT B, A is a target domain, which is understood in terms of a source domain B. |

| 2 | In a similar cognitive-linguistic vein, Silvestre-López and Navarro i Ferrando (2017) discuss metaphors for meditative experience including those for the human mind (such as MIND IS A PERSON, MIND IS AN OBJECT, MIND IS SPACE, MIND IS A LANDSCAPE, and MIND IS A MASS OF WATER). However, this paper deals with entirely metaphors for the two aspects of the mind and their harmonizing. |

| 3 | The Sinographic Buddhist texts used here are contained within the Taishō shinshū daizōkyō 大正新修大藏經 (edited by Takakusu Junjirō 高楠順次郎 and Watanabe Kaigyoku 渡邊海旭, Tokyo: Taishō issaikyō kankōkai, 1924–1932). They are indicated by the text number (“T.”) followed by the volume, page, register (a, b, or c), and when appropriate, line number(s). |

| 4 | According to Buswell and Lopez (2014, p. 221), some Buddhist scholars speculate that the treatise may have been composed first in Sanskrit by the famous Yogācāra scholar Paramārtha after his arrival in China and then translated into Chinese. |

| 5 | |

| 6 | Analyses of journey metaphors in Buddhist discourse from a cognitive linguistic perspective can be found, for example, in Lan (2012); Richardson and Nagashima (2018); and Silvestre-López and Navarro i Ferrando (2017). |

| 7 | These terms are reminiscent of “multiple selves” and “the essential self” discussed in Lakoff and Johnson (1999, pp. 267–89) in relation to the metaphorical conceptualization of our inner lives. However, “the essential self” should not be confused with “the essential mind” referred to in this paper. Our ordinary experience of the former (and multiple selves), which is metaphorically conceptualized, pertains rather to “the phenomenal mind” dealt with in this study. |

| 8 | Cognitive linguistic analyses of moving mind metaphors are also found in Lan (2012) and Silvestre-López and Navarro i Ferrando (2017). |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).