Attitudes and Behaviors Related to Franciscan-Inspired Spirituality and Their Associations with Compassion and Altruism in Franciscan Brothers and Sisters

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Enrolled Persons

2.2. Measures

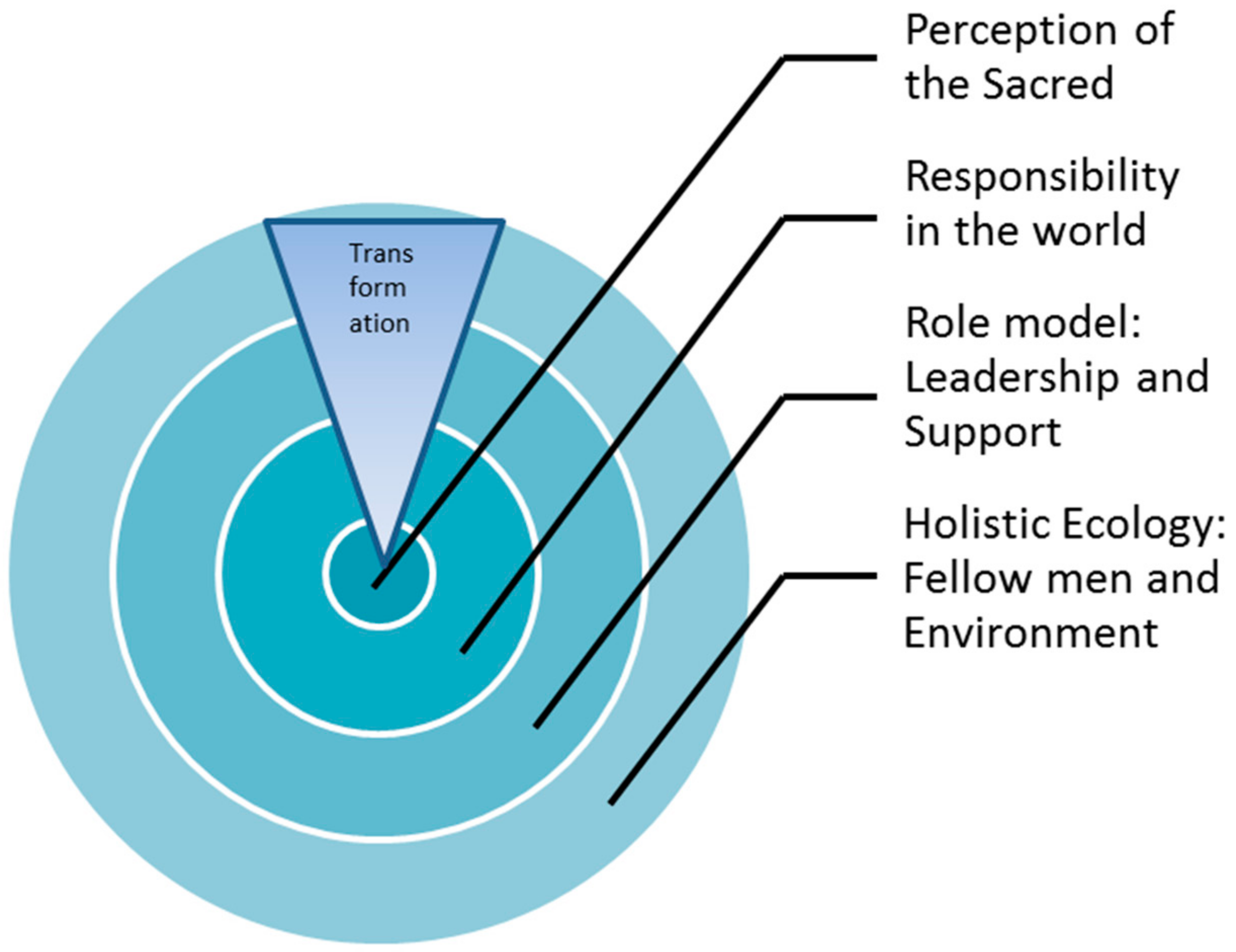

2.2.1. Franciscan Spirituality Questionnaire (FraSpir)

2.2.2. Perception of Religious Lifestyle

2.2.3. Transcendence Perception (DSES-6)

2.2.4. Gratitude and Awe (GrAw-7)

2.2.5. Compassion (SCBCS)

2.2.6. Altruism (GALS)

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Participants

3.2. Expression of FraSpir Attitudes and Behaviors in the Sample

3.3. FraSpir Attitudes and Behaviors and Their Relation to Experiential Forms of Spirituality

3.4. FraSpir Attitudes and Behaviors and Their Relationship to Perceptions of Religious Lifestyle

3.5. FraSpir Attitudes and Behaviors and Their Relationship to Commitement, Compassion, and Altruism

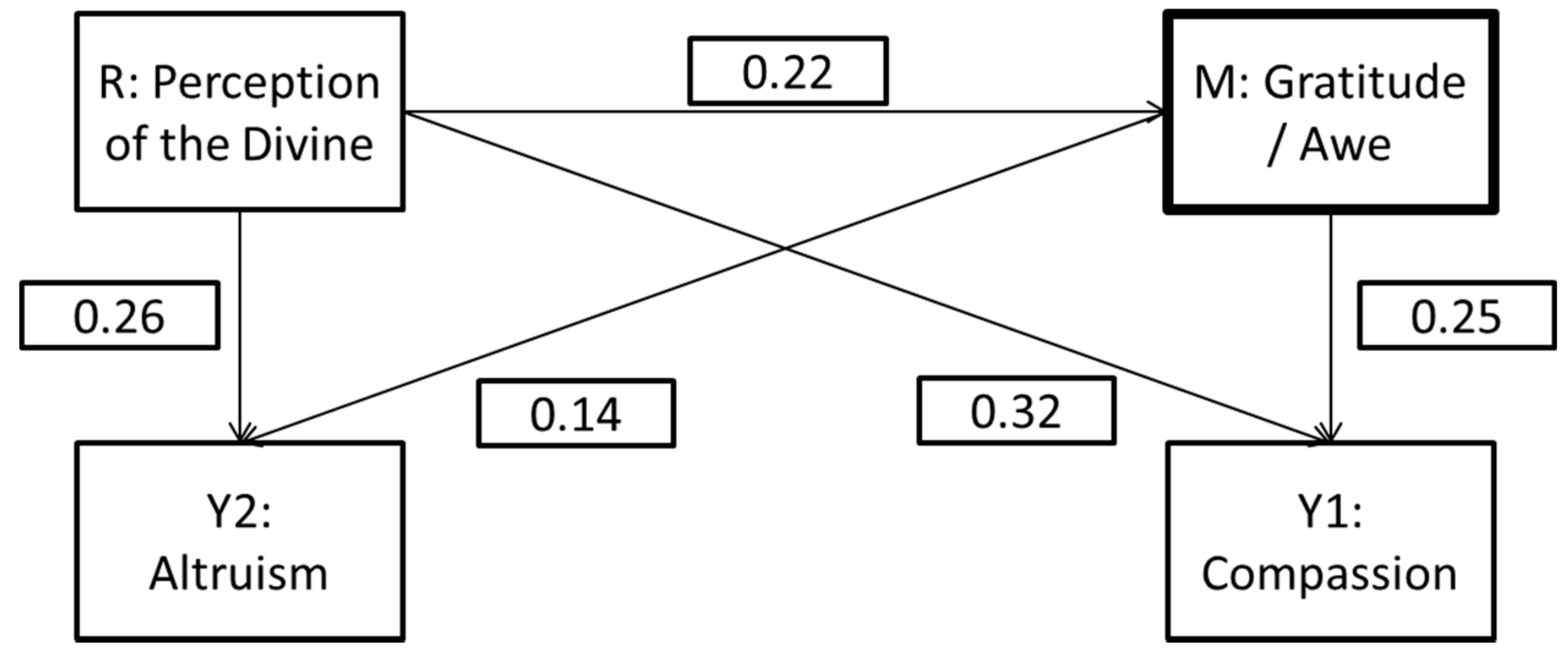

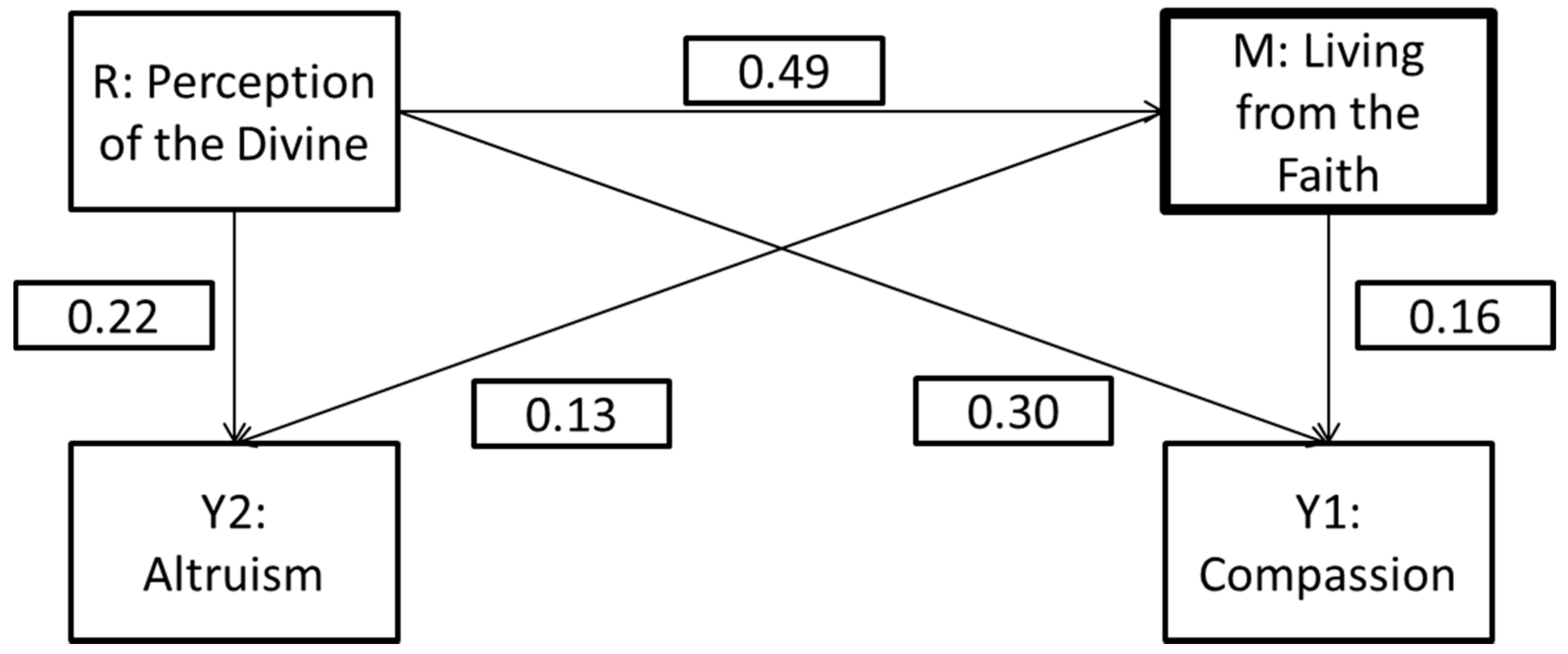

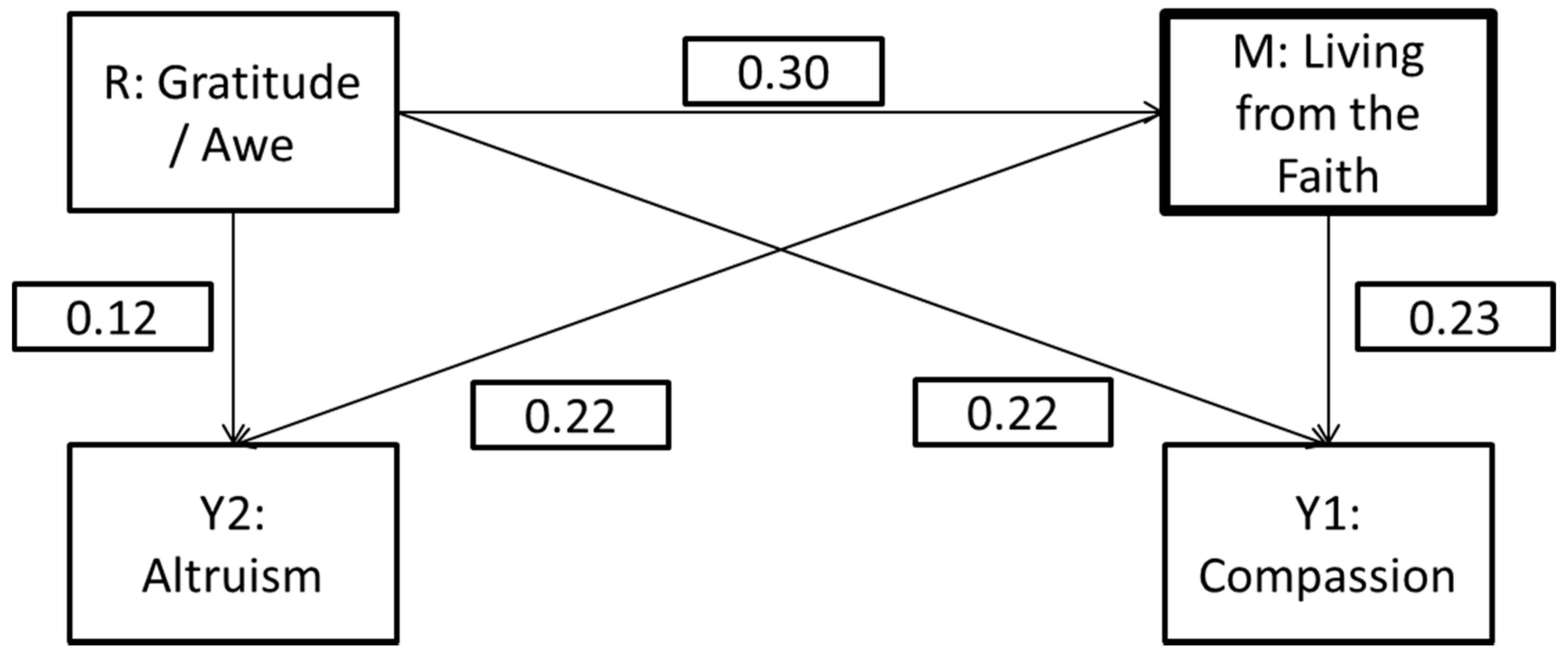

3.6. Mediator Analyses with Compassion and Altruism as Outcomes

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Berrelleza, Erick, Mary L. Gautier, and Mark M. Gray. 2014. Population Trends among Religious Institutes of Women. Special Report Fall 2014. Washington: CARA—Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate, pp. 1–8. Available online: https://cara.georgetown.edu/product/population-trends-among-religious-institutes-of-women-fall-2014/ (accessed on 21 July 2018).

- Blastic, Michael. 1993. Franciscan Spirituality. In The New Dictionary of Catholic Spirituality. Edited by Michael Downey. Collegeville: The Liturgical Press, pp. 408–18. ISBN 978-0-814-65525-2. [Google Scholar]

- Büssing, Arndt, Phillip Kerksieck, Andreas Günther, and Klaus Baumann. 2013. Altruism in Adolescents and Young Adults: Validation of an Instrument to Measure Generative Altruism with Structural Equation Modeling. International Journal of Children’s Spirituality 18: 335–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büssing, Arndt, Markus Warode, Mareike Gerundt, and Thomas Dienberg. 2017. Validation of a novel instrument to measure elements of Franciscan-inspired spirituality in a general population and in religious persons. Religions 8: 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büssing, Arndt, Federico Baiocco, and Klaus Baumann. 2018. Spiritual dryness in Catholic lay persons working as volunteers is related to reduced life satisfaction rather than to indicators of spirituality. Pastoral Psychology 67: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dienberg, Thomas. 2009. Das Leben nach dem Evangelium. Modernes Management und die Regel des heiligen Franziskus. Wissenschaft und Weisheit 71: 196–227. [Google Scholar]

- Dienberg, Thomas. 2013. Economia e spiritualità. Regola francescana e cultura d’impresa. Bologna: Edizioni Dehoniane. [Google Scholar]

- Dienberg, Thomas. 2016. Leiten—Von der Kunst des Dienens. Franziskanische Akzente. Würzburg: Echter-Verlag. ISBN 978-3429039356. [Google Scholar]

- Dienberg, Thomas, and Markus Warode. 2015. Evangelical Poverty and the “Fraternal Franciscan Economy”—New aspects for a reflected business education. Paper presented at the 9th International Conference on Catholic Social Thought and Business Education, Prosperity, Poverty and the Purpose of Business. Rediscovering Integral Human Development in the Catholic Social Tradition, Manila, Philippines, February 26–28. [Google Scholar]

- Ebaugh, Helen Rose. 1993. The Growth and Decline of Catholic Religious Orders of Women Worldwide: The Impact of Women’s Opportunity Structures. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 32: 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, Pope. 2015. Encyclical Letter LAUDATO SI’ of the Holy Father Francis on the Care of Our Common Home. Vatican: Libreria Editrice Vaticana. Available online: http://w2.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/encyclicals/documents/papa-francesco_20150524_enciclica-laudato-si.html (accessed on 21 July 2018).

- Hayes, Andrew F. 2013. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis. New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, Jeong Yeon, Thomas Plante, and Katy Lackey. 2008. The Development of the Santa Clara Brief Compassion Scale: An Abbreviation of Sprecher and Fehr’s Compassionate Love Scale. Pastoral Psychology 56: 421–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jull, Andre. 2001. Compassion: A concept exploration. Nursing Praxis in New Zealand 17: 16–23. [Google Scholar]

- Kuster, Niklaus. 2016. Franziskus. Rebell und Heiliger. Freiburg: Herder. ISBN 978-3-451-30153-7. [Google Scholar]

- Palacios, Santiago Sordo, Thomas P. Gaunt, and Mary L. Gautier. 2015. Population Trends among Religious Institutes of Men. Special Report Fall 2015. Washington: CARA—Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate, pp. 1–8. Available online: https://cara.georgetown.edu/product/religious-institutes-of-men-trends-special-report-fall-2015/ (accessed on 21 July 2018).

- Pessi, Anne Borgitta. 2011. Religiosity and Altruism: Exploring the Link and its Relation to Happiness. Journal of Contemporary Religion 26: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, Frank. 1995. Aus Liebe zur Liebe. Der Glaubensweg des Menschen als Nachfolge Christi in der Spiritualität des hl. Franziskus von Assisi. Kevelaer: Butzon & Bercker. ISBN 978-3-7666-9947-3. [Google Scholar]

- Piliavin, Jane Allyn, and Hong-Wen Charng. 1990. Altruism: A Review of Recent Theory and Research. Annual Review of Sociology 16: 27–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seelig, Beth J., and Lisa S. Rosof. 2001. Normal and Pathological Altruism. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association 49: 933–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spoto, Donald. 2003. Reluctant Saint: The Life of Francis of Assisi. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 0142196258. [Google Scholar]

- Underwood, Lynn G. 2011. The Daily Spiritual Experience Scale: Overview and Results. Religions 2: 29–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Underwood, Lynn G., and Jeanne A. Teresi. 2002. The Daily Spiritual Experience Scale: Development, Theoretical Description, Reliability, Exploratory Factor Analysis, and Preliminary Construct Validity Using Health-Related Data. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 24: 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, Christopher R. 2008. Compassion, Suffering and the Self. A Moral Psychology of Social Justice. Current Sociology 56: 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Living from the Faith | Peaceful Attitude/Respectful Treatment | Commitment to the Disadvantaged | Seeking God in Silence and Prayer | Commitment to the Creation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cronbach’s alpha | 0.845 | 0.835 | 0.805 | 0.723 | 0.631 |

| f1 My faith is my orientation in life | 0.799 | ||||

| f2 I live in accordance with my religious beliefs | 0.771 | ||||

| f4 My faith/spirituality gives meaning to my life | 0.760 | ||||

| f5 I try to track down the divine in the world | 0.675 | ||||

| f6 I have a sense of the Sacred in my life | 0.631 | 0.333 | |||

| f11 I feel a longing for nearness to God | 0.563 | 0.408 | |||

| f24 I check my attitudes and views, because others might be right | 0.772 | ||||

| f23 I understand the positions and opinions of other people and to accept them internally | 0.737 | ||||

| f22 I try to put myself into others and wonder how I would feel in their situation | 0.711 | 0.304 | |||

| f26 In conflicts, I always try to find ways of reconciliation | 0.665 | ||||

| f25 I actively go to people who are not on good terms with me, and try to clarify the causes | 0.612 | 0.409 | |||

| f21 I am conscious of the fact that I deal with others well and respectfully | 0.355 | 0.543 | |||

| f15 I actively engage for the well-being of disadvantaged people | 0.831 | ||||

| f20 I actively engage in the social field | 0.789 | ||||

| f18 I try to find ways to help people in need | 0.306 | 0.762 | |||

| f8 I maintain times of silence before God | 0.767 | ||||

| f9 Before important decisions, I seek advice in prayer | 0.363 | 0.694 | |||

| f10 I always try to remain a seeker | 0.388 | 0.526 | |||

| f14 I am awed by the beauty of God’s creation (i.e., persons, animals, plants, landscapes etc.) | 0.311 | 0.686 | |||

| f16 I am actively involved in the protection and maintenance of creation | 0.526 | 0.635 | |||

| f12 I maintain humble dealings with the resources entrusted to me | 0.634 |

| Scores | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) (Mean ± SD) | 61 ± 25 |

| Gender (%) | |

| Women | 45.5 |

| Men | 55.5 |

| Franciscan Communities (%) | |

| Franciscans (m/f) | 31 |

| Capuchins (m) | 27 |

| Poor Clares (f) | 9 |

| Other (m/f) | 33 |

| Self-perception (% agreement) | |

| Charitably engaged person | 88 |

| Contemplative person | 12 |

| Perception of religious lifestyle (% agreement) | |

| Community lives rather ‘separated’ from the people in our area | 31 |

| People care a lot about our lifestyle | 63 |

| Community has so much to offer to the world | 89 |

| Living from the Faith | Seeking God in Silence and Prayer | Peaceful Attitude/Respectful Treatment | Commitment to the Disadvantaged | Commitment to the Creation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | 0–4 | 0–4 | 0–4 | 0–4 | 0–4 | |

| All (n = 373) | Mean | 3.62 | 3.38 | 3.04 | 2.91 | 3.10 |

| SD | 0.47 | 0.63 | 0.06 | 0.81 | 0.63 | |

| All (n = 373) | z-Mean * | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.00 |

| z-SD * | 0.94 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Gender | ||||||

| Men (n = 207) | z-Mean | −0.12 | −0.21 | −0.13 | −0.12 | −0.11 |

| z-SD | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 1.00 | 0.97 | |

| Women (n = 166) | z-Mean | 0.19 | 0.28 | 0.18 | 0.14 | 0.13 |

| z-SD | 0.84 | 0.92 | 1.00 | 0.98 | 1.03 | |

| F value | 10.19 | 23.46 | 9.18 | 6.66 | 5.33 | |

| p value | 0.002 | <0.0001 | 0.003 | 0.010 | 0.021 | |

| Self-view | ||||||

| Charitable (n = 310) | z-Mean | −0.02 | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.02 |

| z-SD | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.97 | 0.98 | 1.00 | |

| Contemplative (n = 42) | z-Mean | 0.32 | 0.35 | −0.15 | −0.30 | −0.04 |

| z-SD | 0.78 | 0.78 | 1.10 | 1.14 | 1.09 | |

| F value | 4.71 | 5.96 | 1.09 | 4.45 | 0.10 | |

| p value | 0.031 | 0.015 | n.s. | 0.036 | n.s. | |

| Mean ± SD (Theoretical Range) | Living from the Faith | Seeking God in Silence and Prayer | Peaceful Attitude/Respectful Treatment | Commitment to the Disadvantaged | Commitment to the Creation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Franciscan-inspired spirituality (FraSpir RO) | ||||||

| Living from the Faith | 3.6 ± 0.6 (0–4) | 1.000 | ||||

| Seeking God in Silence and Prayer | 3.4 ± 0.6 (0–4) | 0.612 ** | 1.000 | |||

| Peaceful Attitude/Respectful Treatment | 3.0 ± 0.6 (0–4) | 0.454 ** | 0.430 ** | 1.000 | ||

| Commitment to the Disadvantaged | 2.9 ± 0.8 (0–4) | 0.262 ** | 0.258 ** | 0.480 ** | 1.000 | |

| Commitment to the Creation | 3.1 ± 0.6 (0–4) | 0.398 ** | 0.422 ** | 0.538 ** | 0.482 ** | 1.000 |

| Experiential aspects of spirituality | ||||||

| Perception of the Divine (DSES-6) | 27.8 ± 5.8 (6–36) | 0.512 ** | 0.376 ** | 0.474 ** | 0.336 ** | 0.446 ** |

| Gratitude/Awe (GrAw-7) | 16.5 ± 3.4 (0–21) | 0.513 ** | 0.388 ** | 0.421 ** | 0.325 ** | 0.506 ** |

| Perception of religious lifestyle | ||||||

| FS1 Community lives ‘separated’ | 1.8 ± 1.2 (0–4) | 0.023 | 0.030 | −0.047 | −0.120 | −0.007 |

| FS2 Community has so much to offer | 3.4 ± 0.8 (0–4) | 0.301 ** | 0.271 ** | 0.330 ** | 0.231 ** | 0.315 ** |

| FS3 People care a lot about our lifestyle | 2.8 ± 1.0 (0–4) | 0.296 ** | 0.253 ** | 0.264 ** | 0.213 ** | 0.309 ** |

| Prosocial care for others | ||||||

| Compassion (SCBCS) | 6.1 ± 0.5 (1–7) | 0.321 ** | 0.233 ** | 0.448 ** | 0.365 ** | 0.449 ** |

| Altruism (GALS) | 1.6 ± 0.5 (0–3) | 0.262 ** | 0.208 ** | 0.383 ** | 0.369 ** | 0.234 ** |

| Dependent Variable: Compassion Model 7: F = 23.9, p < 0.001; R2 = 0.34 | Beta | T | p |

| (constant) | 12.211 | 0.000 | |

| Peaceful Attitude/Respectful Treatment (FraSpr RO) | 0.182 | 2.891 | 0.004 |

| Gratitude/Awe (GrAw-7) | 0.218 | 3.754 | 0.000 |

| Commitment to the Creation (FraSpir RO) | 0.155 | 2.617 | 0.009 |

| FS2 Community has so much to offer to the world | 0.149 | 2.997 | 0.003 |

| Seeking God (FraSpir RO) | −0.168 | −3.027 | 0.003 |

| Perception of the Divine (DSES) | 0.125 | 2.115 | 0.035 |

| Commitment to the Disadvantaged (FraSpir RO) | 0.106 | 1.972 | 0.049 |

| Not significant in the model: Living from the Faith (FraSpir RO) | |||

| Dependent Variable: Altruism Model 5: F = 21.0, p < 0.001; R2 = 0.25 | Beta | T | p |

| (constant) | 1.380 | 0.169 | |

| Commitment to the Disadvantaged (FraSpir RO) | 0.259 | 4.386 | 0.000 |

| Gratitude/Awe (GrAw-7) | 0.250 | 4.388 | 0.000 |

| Peaceful Attitude/Respectful Treatment (FraSpr RO) | 0.181 | 2.803 | 0.005 |

| Commitment to the Creation (FraSpir RO) | −0.156 | −2.458 | 0.015 |

| FS2 Community has so much to offer to the world | 0.115 | 2.191 | 0.029 |

| Not significant in the model: Living from the Faith (FraSpir RO), Seeking God (FraSpir RO), Perception of the Divine (DSES) | |||

| Variables | Mediator (Gratitude/Awe) | Y1 (Compassion) | Y2 (Altruism) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | p | β | SE | p | β | SE | p | |

| X (DSES) | 0.22 | 0.04 | <0.001 | 0.32 | 0.05 | <0.001 | 0.26 | 0.05 | <0.001 |

| M (GrAw) | - | - | - | 0.25 | 0.06 | <0.001 | 0.14 | 0.06 | 0.02 |

| Constant | −0.01 | 0.04 | 0.87 | −0.01 | 0.05 | 0.97 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.93 |

| R2 = 0.07 | R2 = 0.19 | R2 = 0.10 | |||||||

| F(1,327) = 25.89, p < 0.001 | F(2,326) = 38.66, p < 0.001 | F(2,322) = 18.48, p < 0.001 | |||||||

| Variables | Mediator “Living from the Faith” | Y1 (Compassion) | Y2 (Altruism) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | p | β | SE | p | β | SE | p | |

| X1 (DSES) | 0.49 | 0.05 | <0.001 | 0.30 | 0.06 | <0.001 | 0.22 | 0.06 | <0.01 |

| M (Living from Faith) | - | - | - | 0.16 | 0.06 | <0.01 | 0.13 | 0.06 | 0.03 |

| Constant | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.82 | −0.01 | 0.05 | 0.96 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.99 |

| R2 = 0.26 | R2 = 0.16 | R2 = 0.10 | |||||||

| F(1,324) = 112.22, p < 0.001 | F(2,328) = 32.18, p < 0.001 | F(2,323) = 18.11, p < 0.001 | |||||||

| Variables | Mediator “Living from the Faith” | Y1 (Compassion) | Y2 (Altruism) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | p | β | SE | p | β | SE | p | |

| X2 (GrAw) | 0.30 | 0.06 | <0.001 | 0.22 | 0.06 | <0.01 | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| M (Living from Faith) | - | - | - | 0.23 | 0.05 | <0.001 | 0.22 | 0.05 | <0.01 |

| Constant | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.90 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.87 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.99 |

| R2 = 0.07 | R2 = 0.12 | R2 = 0.07 | |||||||

| F(1,339) = 26.96, p < 0.001 | F(2,338) = 23.67, p < 0.001 | F(2,334) = 12.70, p < 0.001 | |||||||

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Büssing, A.; Recchia, D.R.; Dienberg, T., OFMCap. Attitudes and Behaviors Related to Franciscan-Inspired Spirituality and Their Associations with Compassion and Altruism in Franciscan Brothers and Sisters. Religions 2018, 9, 324. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9100324

Büssing A, Recchia DR, Dienberg T OFMCap. Attitudes and Behaviors Related to Franciscan-Inspired Spirituality and Their Associations with Compassion and Altruism in Franciscan Brothers and Sisters. Religions. 2018; 9(10):324. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9100324

Chicago/Turabian StyleBüssing, Arndt, Daniela R. Recchia, and Thomas Dienberg, OFMCap. 2018. "Attitudes and Behaviors Related to Franciscan-Inspired Spirituality and Their Associations with Compassion and Altruism in Franciscan Brothers and Sisters" Religions 9, no. 10: 324. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9100324

APA StyleBüssing, A., Recchia, D. R., & Dienberg, T., OFMCap. (2018). Attitudes and Behaviors Related to Franciscan-Inspired Spirituality and Their Associations with Compassion and Altruism in Franciscan Brothers and Sisters. Religions, 9(10), 324. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9100324