1. Introduction

An understanding of youth attitudes of the built environment is an area which has received growing attention since the introduction of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989). Planners and designers are keen to improve the quality of life for local communities, and therefore need to understand how people and young people in particular, use, perceive and value their environments (

Passon 2008). Much research has explored public opinion of and participation in built heritage regeneration, although the majority has been from an adult viewpoint. Interestingly, the research emphasises the important role that cultural heritage plays as part of societal and community well-being (

Tweed and Sutherland 2007). Research by

Coeterier (

2002) also highlights the fact that historic buildings have an existential value to people in the sense that they give or enhance place identity, personal identity and group identity. This study clearly shows that this value is an important feature of environmental quality for the general public. Importantly, it has been shown that the value of architecture lies not only in aesthetic, scientific, symbolic, historic and cultural terms but also in economic terms (

Giannakopoulou et al. 2017).

Despite a deeper understanding of the built environment emerging in recent years, little is known in the United Kingdom and Ireland about youth attitudes to the physical and built environment, especially religious buildings which can strongly influence the shaping of local communities and attribute greatly to cultural heritage.

In Northern Ireland, church buildings often provide both stability and security of local identity (

Brown and Perkins 1992). The visual impact of church architecture, and equally their siting, has been tied to the sense of identity, attachment and belonging within local communities (

Mitchell 2006). Settlement patterns within the city have altered over the years and this has resulted in many churches being abandoned. These derelict buildings have a negative impact on the visual, social and economic development of local areas.

Through a detailed case study of a disused Methodist church set in an interface area, this study funded by the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) Research Trust Award, investigated and aimed to establish the building’s influence on local identity and place attachment from a youth perspective with those aged 11–14. Youth were specifically asked to reflect on the regeneration potential of the heritage building, providing their thoughts through drawing. This particular study attempted to consider if a renewed understanding of such a building, from a youth perspective, could help find a way for disused space to once again play a viable part in the local community as a shared heritage resource.

The selected building, Carlisle Memorial Methodist Church, is located on the edge of inner city Belfast and is considered by many to be a landmark building, serving as a gateway to North Belfast. Carlisle Memorial Methodist church is a distinguished building constructed at the sole expense of Alderman James Carlisle in memory of his only son. The building consists of a church, erected in 1875–1876, and an adjoining Sunday school erected in 1888–1889. These two buildings were connected by a cloister, over which was the church parlour. The church was named after Lord Carlisle, Viceroy of Ireland, and Belfast builder Alderman James Carlisle.

Designed in the Gothic revival style by noted architect W. H Lynn, the church housed one of the largest Methodist congregations in Belfast. As can be seen in

Figure 1, the church is a double-height Gothic Revival church, constructed of Armagh limestone and pink Dundonald sandstone. The church is cruciform by plan, aligned NE–SW with full height side aisles and tall three-stage tower with a spire in the north corner (

Hall Black Douglas in association with Alastair Coey Architects 2011). The church building measures approximately 815 m

2 and the interior comprises nave and side aisles supported on clustered colonnettes. The roof of the building is formed by three main pitched sections with a slate covering. At eaves level, parapet walls have been adopted with gutter lines located behind them. The roof construction consists of traditional cut rafters, supported on timber purlins and trusses (

Doran Consulting 2011).

As a consequence of the declining congregation and its location at a major religious and political interface area, the church has been empty since its closure in 1982. Since then, it has suffered from extensive physical degradation until the Belfast Building Trust launched a major campaign in 2008 to ensure the church survived to play an active role in the economic, social and physical regeneration of the local historic area of Belfast.

According to the Belfast Building Preservation Trust (

BBT 2009) its dereliction was a cipher for the state of the community. The Carlisle Circus area, along with the Crumlin and Antrim Roads in particular, and North Belfast in general, has suffered heavily from economic and social decline over the past 35 years. The population of the area has declined significantly and the political situation has had a detrimental effect on the economic and social development of the area. According to the Dunlop Report (

Dunlop et al. 2002) the area faces major socioeconomic problems, including high levels of deprivation, high levels of out-migration, high levels of unemployment, low educational attainment levels, significant youth issues (including low levels of aspiration and related crime/community safety issues), many serious health problems, and a lack of clear single identity with rather a series of small, often isolated communities that are highly segregated. The report also adds that ‘the area’s poor social and economic conditions are reflected in and exacerbated by the physical condition of North Belfast including high rates of dereliction and redundant industrial land’.

Fortunately, through the efforts of the Belfast Building Trust, Carlisle Memorial Methodist Church, was placed on the Worlds Monument Fund watch list (

Worlds Monument Fund 2017). The watch list is published every two years and aims to protect sites of cultural or architectural importance, which are at risk because of neglect, vandalism, conflict or disaster. Since being placed on the watch list, interest in the building has increased dramatically, and under the direction of the Belfast Building Trust, the process of restoring and developing a sustainable re-use option for the church building has begun.

This paper will document the youth engagement process with Carlisle Memorial Methodist Church, initially by reviewing relevant literature pertaining to youth participation in planning. Furthermore, an overview of the historical and social significance of sacred space will be examined. The latter sections of this paper will detail the methodological approach adopted to encourage youth participation with the building, in addition to an analysis of the key findings highlighting youth opinion and visions for the future of the building.

2. Youth Participation in Planning

Fortunately, since the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989), the field of planning has begun to recognise youth as an important stakeholder group. Whilst there is no universally accepted definition of adolescence and youth, for the purpose of this paper, youth will be defined as any child under the age of 18, in accordance with United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (

UNICEF 2017). However, specifically within this study, the youth cohort that participated were those between the ages of 11 and 14. According to

Matthews (

2001) young people of this age range (under 18) are ‘seemingly invisible in decision making processes’ but much can be gained for their inclusion in developing the built environment. Planning has far-reaching implications for youth because they are the generation that will experience the results of any planning decisions the longest (

Frank 2006). The size of the youth population and their feelings of social isolation are two several compelling reasons for planners to pay attention to youth (

Frank 2006). Youth aged 11–17 are of particular concern as this neglected social grouping is unable to vote and as such has less political power, yet like adults they are users of the physical and built environment.

Matthew et al. (

1999) argue that gaining partial understanding of youth needs is better than not attempting to understand, and that with care, sensitivity, and the use of appropriate methodologies, research should be able to get closer to the taken for granted words of young people.

The potential benefits of youth participation have been highlighted and summarised by

Frank (

2006). The involvement can impact positively on youth knowledge and skills as well as attitudes and behaviour. In terms of knowledge and skills, youth can learn about the local community and environment, learn how to create community changes, and develop skills such as those associated with research and design, communication and collective decision-making. Studies have also demonstrated improvements in youth confidence and assertiveness as well as improved enthusiasm for planning and community involvement. They also directly benefit as a result of the educational, entertainment, or networking aspects of the planning process, and youth appreciate having a voice in public affairs (

Frank 2006). Research (

Checkoway 1995;

Hart 1997;

Chawla 2002;

Sinclair 2004) has identified that some benefits are immediately present, while others accumulate or surface over time, and indeed many are similar to those achieved through adult participation (

Frank 2006). By enabling youth to have responsibility and a voice; communities can thrive and generate greater cultural awareness and understanding. This is of particular importance in tensioned societies such as Northern Ireland.

Lederach (

1997) emphasises the important role of community involvement and states that people in conflict or tensioned settings should be seen as resources rather than recipients. Consultation must be taken across all age ranges of the community and not be focused solely on people with considerable knowledge of the history of the area and vocal stakeholder groups such as historical societies (

Spennemann 2006).

3. Significance of Sacred Space

Little is known about youth opinions of the built environment and in particular disused religious buildings, which can become a significant part of local cultural heritage. Youth connection and community attachment to sacred places has also been largely ignored, minimized or marginalised. If we consider church spaces as significant to the physiological well-being of community, as these places contribute fundamentally to a sense of place and belonging, then it follows that we have to ensure the community’s views are actively sought in the identification of heritage assets.

Religious buildings are widely recognised for the invaluable contribution they make to society, to the heritage of the nation and to the vibrancy of community life (

National Churches Trust 2011). The benefits of church buildings to society have also been emphasised by

Hobohm (

2008) who determined that the significance church buildings have had in history exceeds their sole function as a place of Christian worship. The church has been an important place for communities, providing not only a place for worship but a central location in which to encourage and nurture community spirit. These buildings are able to therefore offer an architectural and cultural distinctiveness, enabling them to serve as local landmarks and establishing identities for districts (

Duckworth 2010).

In the city of Belfast, religious spaces are generally ‘church spaces’, which are often historically used to interpret local identity and to forge politically useful connections to the past (

Vale 1999). Religion still plays an important role in shaping the social behaviour of many communities, a fact reflected in statistics indicating a significant number of regular adult churchgoers in Northern Ireland (45%) compared to 18% in Scotland; 14% in England and 12% in Wales (

Ashworth and Farthing 2007). Unfortunately, little information is available on church attendance rates for young people aged 16 and below. Despite the lack of statistical age-related data, religious buildings in Northern Ireland appear to play a unique and vital role in shaping society as well as providing spaces for young people to learn about their faith and culture (

McPhillips and Russell 2011).

Belfast’s religious buildings often reflect decades of society-wide sectarian conflict and Carlisle Memorial Methodist Church is no exception. On the edge of inner-city Belfast, Carlisle Memorial Methodist Church serves as a sober reminder of Belfast’s architectural legacy and its troubled past (

BBT 2009). Despite the building’s poor state, it is considered to be a local landmark and as such its historical and social significance must be reflected in its future redevelopment. The redevelopment of Carlisle Memorial Methodist Church has the potential to revitalise the local community by providing positive shared space. In order to find a sustainable use for this building, it is important that youth opinions of built heritage, disused space and religious space are established.

Whilst research suggests that religious buildings are important assets, serving the local community for worship and the wider community for outreach, little research has investigated the implications of disused or redundant churches on local communities and associated identity. The problem of redundant religious buildings is common to many countries including Great Britain and Northern Ireland. The available UK statistics are limited but estimates are that the Church of England closes around 20 church buildings each year, while approximately 200 Danish churches have been deemed nonviable, and the Catholic Church in Germany has shut down about 515 churches in the past ten years. In the Netherlands the situation is bleaker still, and Catholic leaders estimate that two-thirds of their 1600 churches will be out of commission in a decade, with 700 of Holland’s Protestant churches expected to close within four years (

Bendavid 2015;

Church of England 2017).

Whilst closed and vacant churches have become a more common presence in the urban landscape, and whilst a desire often exists to save or preserve a former church, these buildings have proven particularly challenging to covert to other uses (

Kiley 2004). There is no doubt that the best use for a historic building is its original use, but with the recent rise in redundant church buildings, questions have been raised over the future use of disused churches. According to

Bishop (

2009) when a church becomes redundant as a place of worship its options are either retention as a monument, demolition (which often represents that the community has failed), creative re-use (which often indicates that the community has a feeling for the future), or continued religious use by another denomination.

Bishop (

2009) also argues that in order to achieve a successful re-use of church buildings, it is first necessary to carry out an evaluation of a building’s significance in local, regional and national terms and then to establish its potential significance as an urban resource within the community as a whole.

Despite the lack of statistics providing details on the number of redundant churches in Northern Ireland, it is clear that local churches occupy a key position in the region’s architectural heritage. Disused churches in Northern Ireland have unfortunately been targets of vandalism and environmental decay, especially those set in opposing communities or interface areas. The impact of the demolition or continued decay of these building in Northern Ireland is unknown, however, previous research by

Latham (

2000) suggests that demolition or decay of such buildings may have a negative impact on communities’ emotional well-being as the value of the building is placed in jeopardy. It would therefore be interesting to understand opinion from a youth perspective of such disused buildings as young people are also a valuable group and key part of any local community.

4. Methodology

The methodological approach for this project was two-fold; firstly, the development of a detailed case study account of Carlisle Memorial Methodist Church in terms of its contextual and historical significance, documenting its subsequent demise, and secondly, the development of a mixed methodology which encompassed the novel use of drawings and youth focused workshops, to enable youth perceptions and accounts to be documented in relation to the redevelopment of Carlisle Memorial Methodist Church.

4.1. Youth Selection

The selection of the youth participants was initially determined by their age range and location to the case study building. A local mixed secondary school, both in gender and religious denominations, located close to Carlisle Memorial Methodist Church, agreed to contribute to the study. Therefore, the researchers were able to visit the school on a number of occasions to conduct the workshops. Access was granted to class years 1–3 (ages 11–14), primarily as the School felt the project best aligned with their learning objectives and class availability. From the participants, 48% were female and 52% were male. In terms of religious affiliation, it was found that 48% of the participants classified themselves as Protestant, 13% Christian, 16% Catholic, 8% Atheist and the remaining as Jewish, Buddhist, Celtic Pagan, or as belonging to Christian mixed religions.

4.2. Workshops

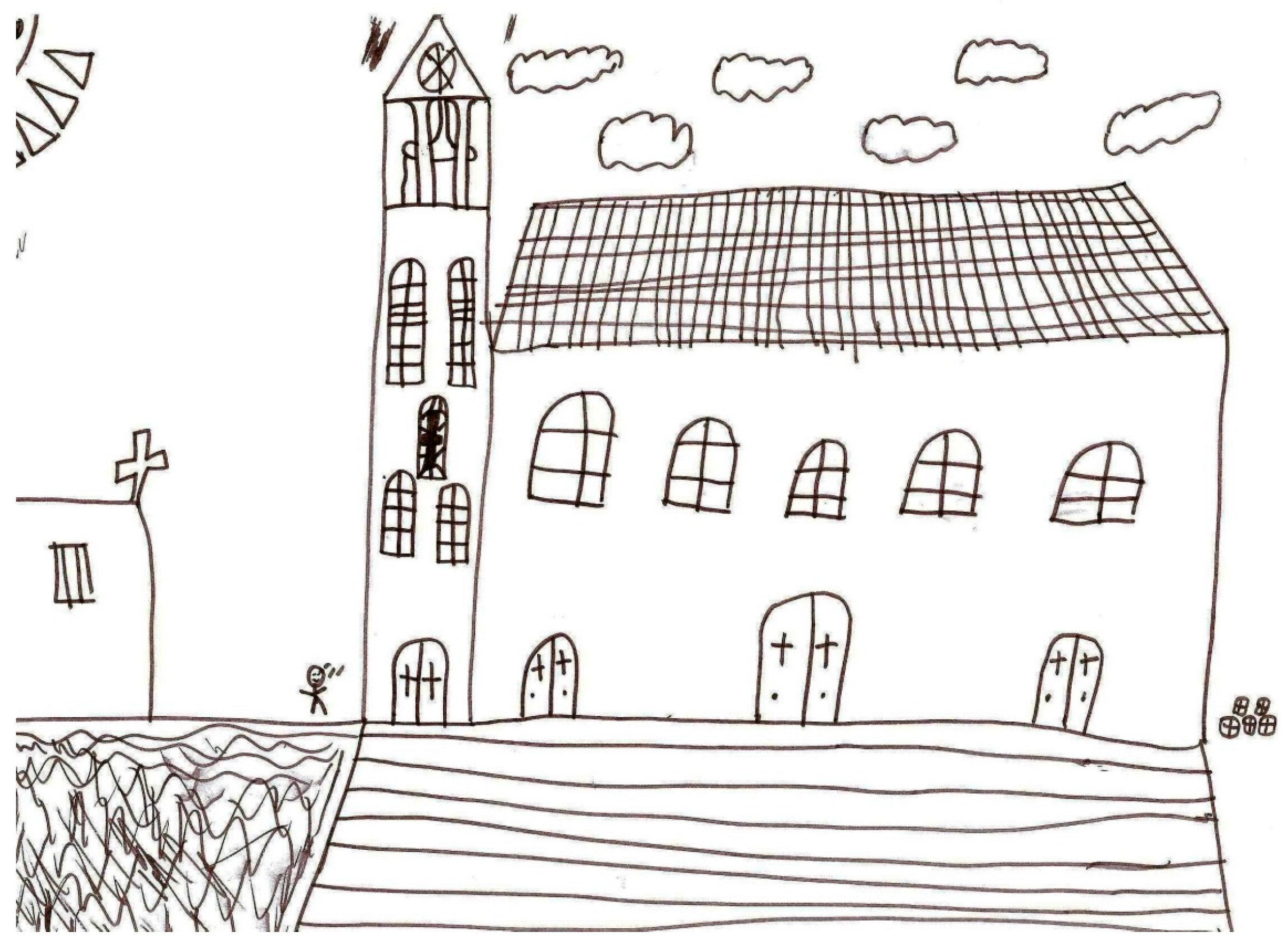

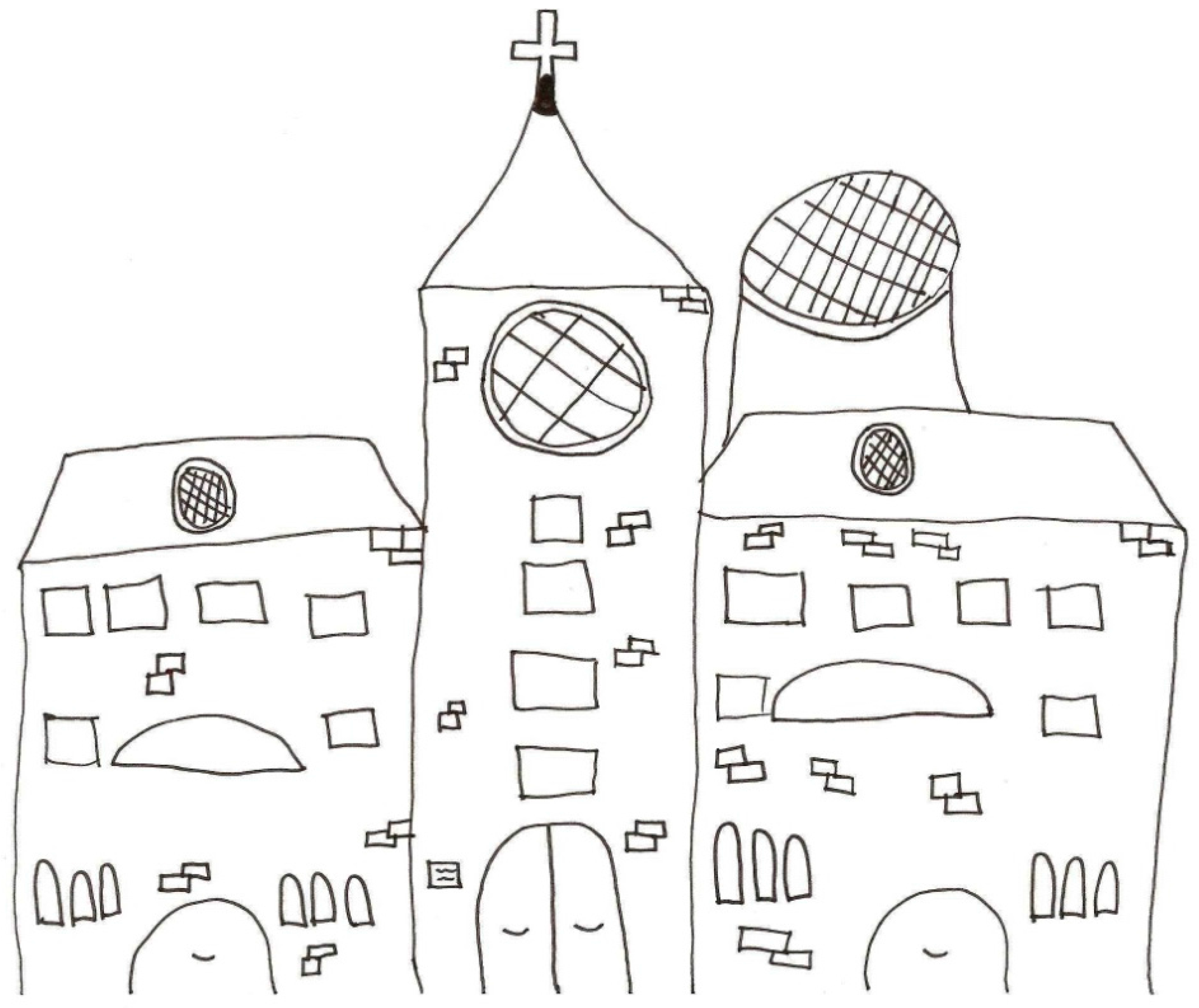

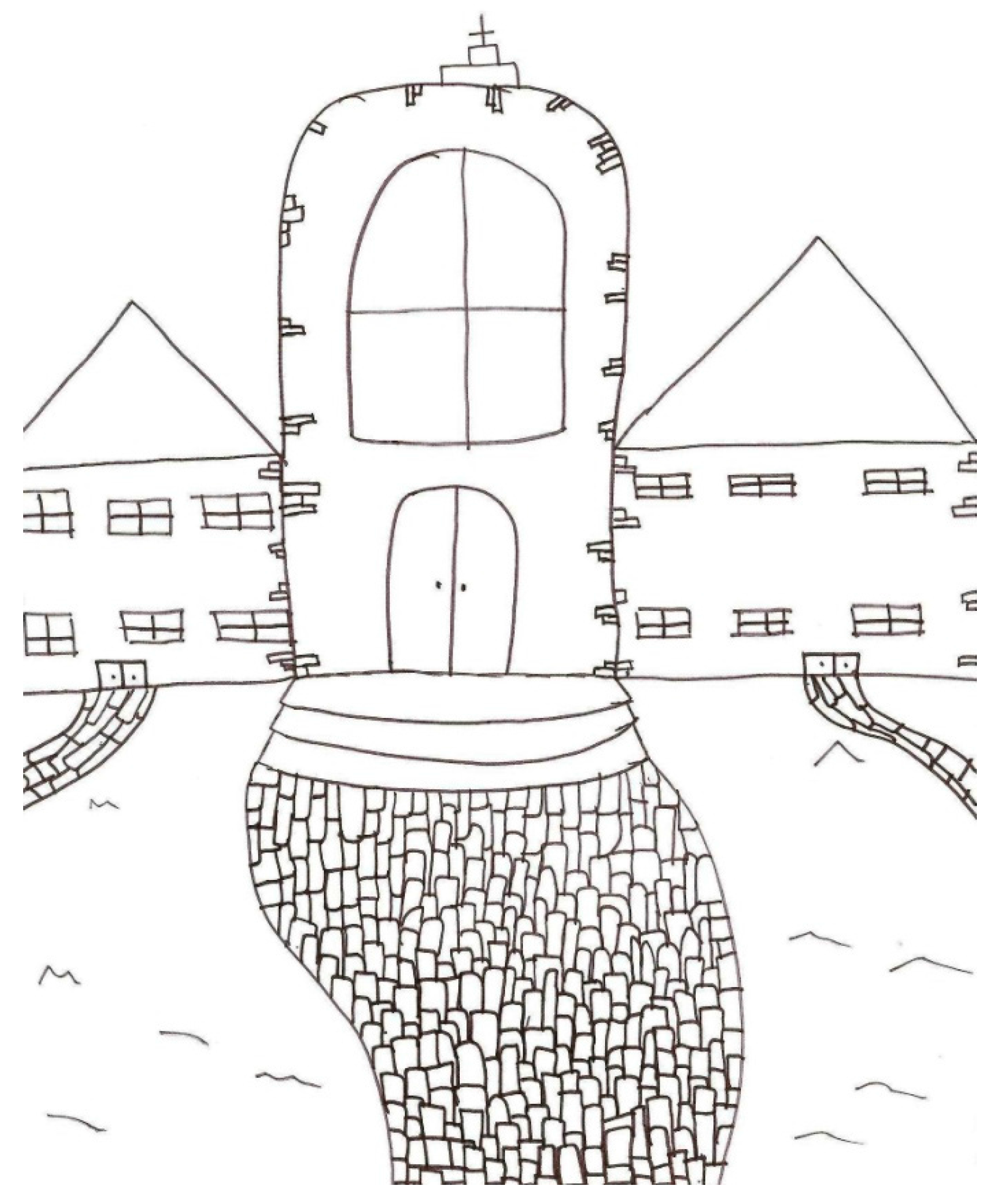

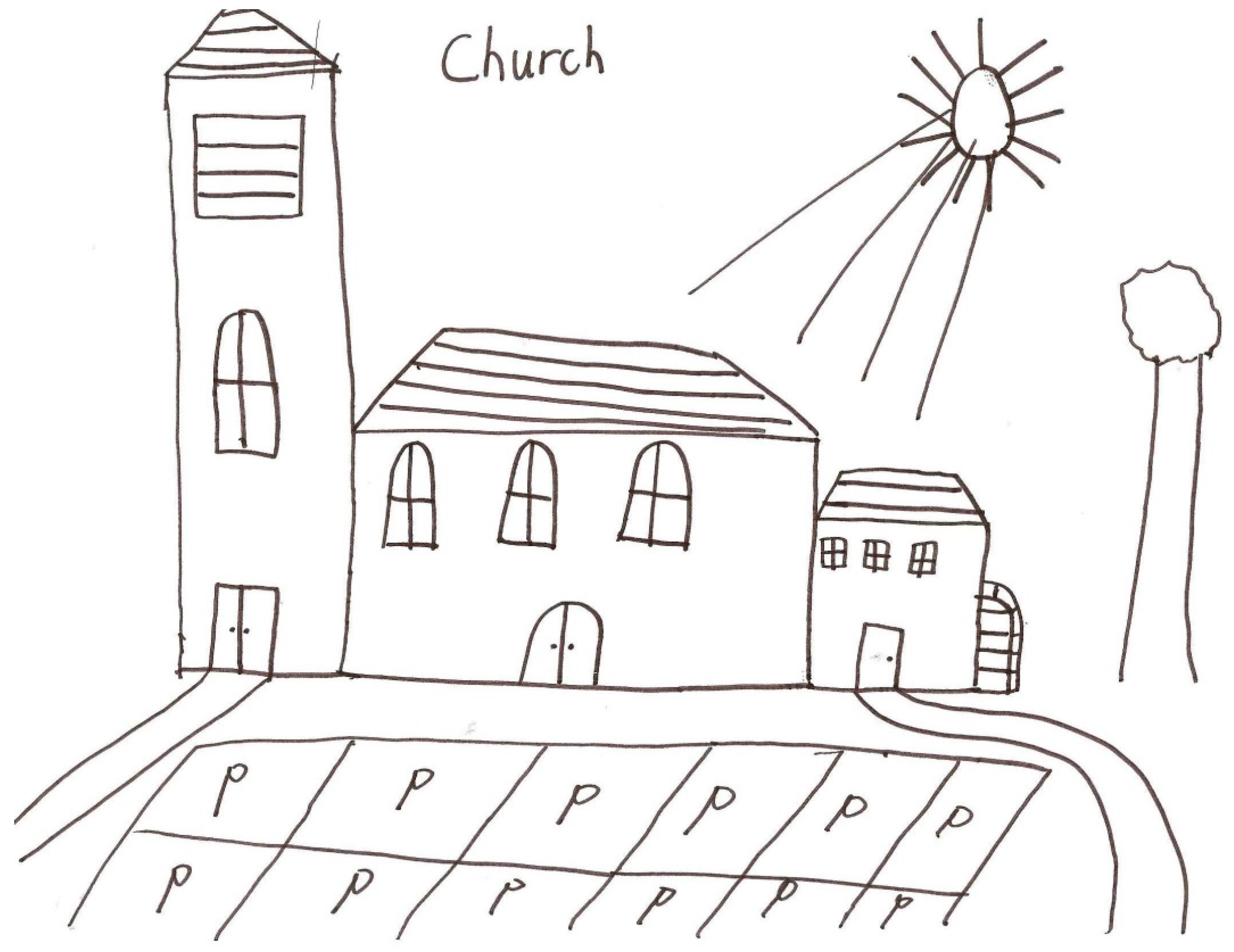

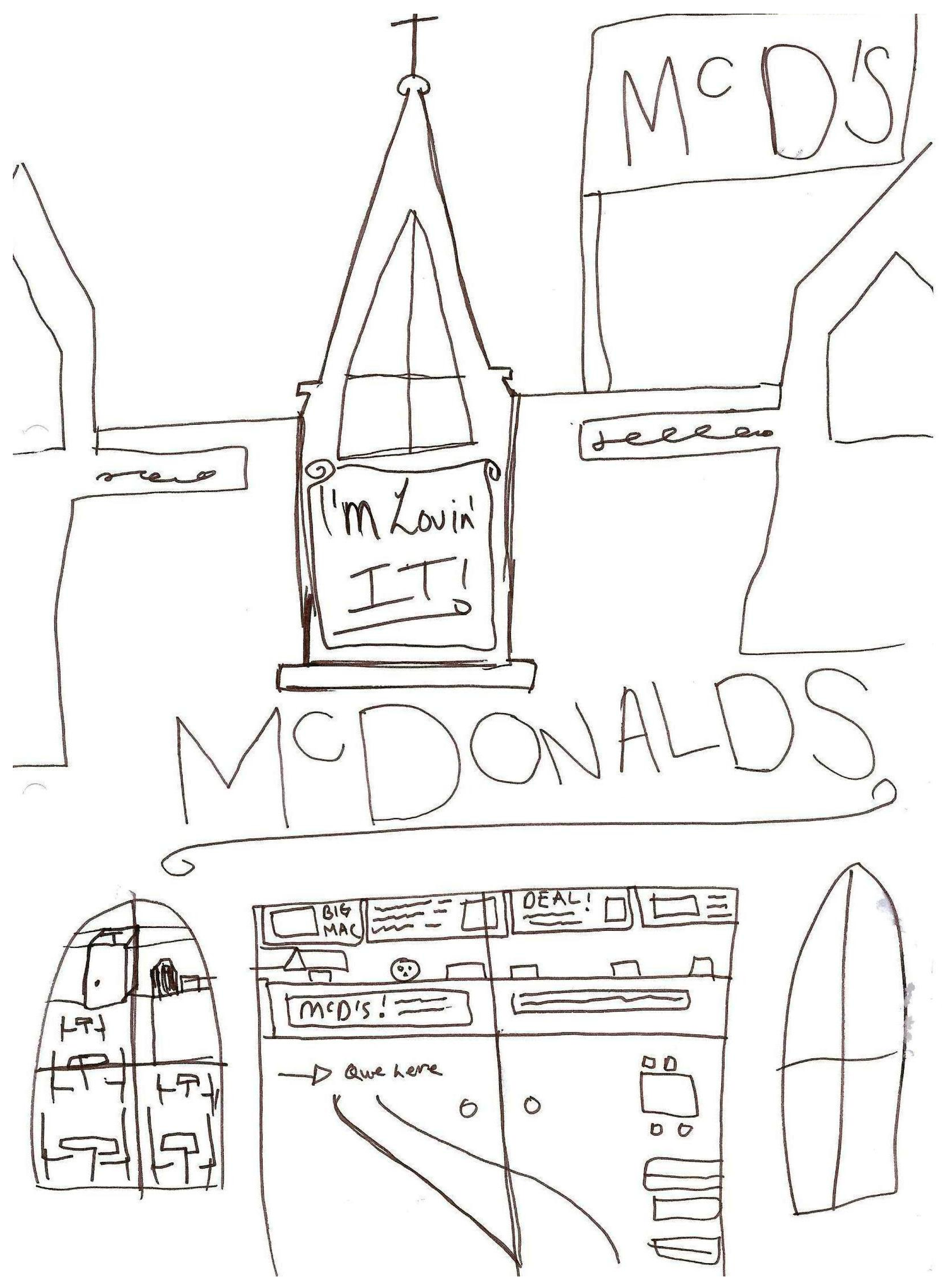

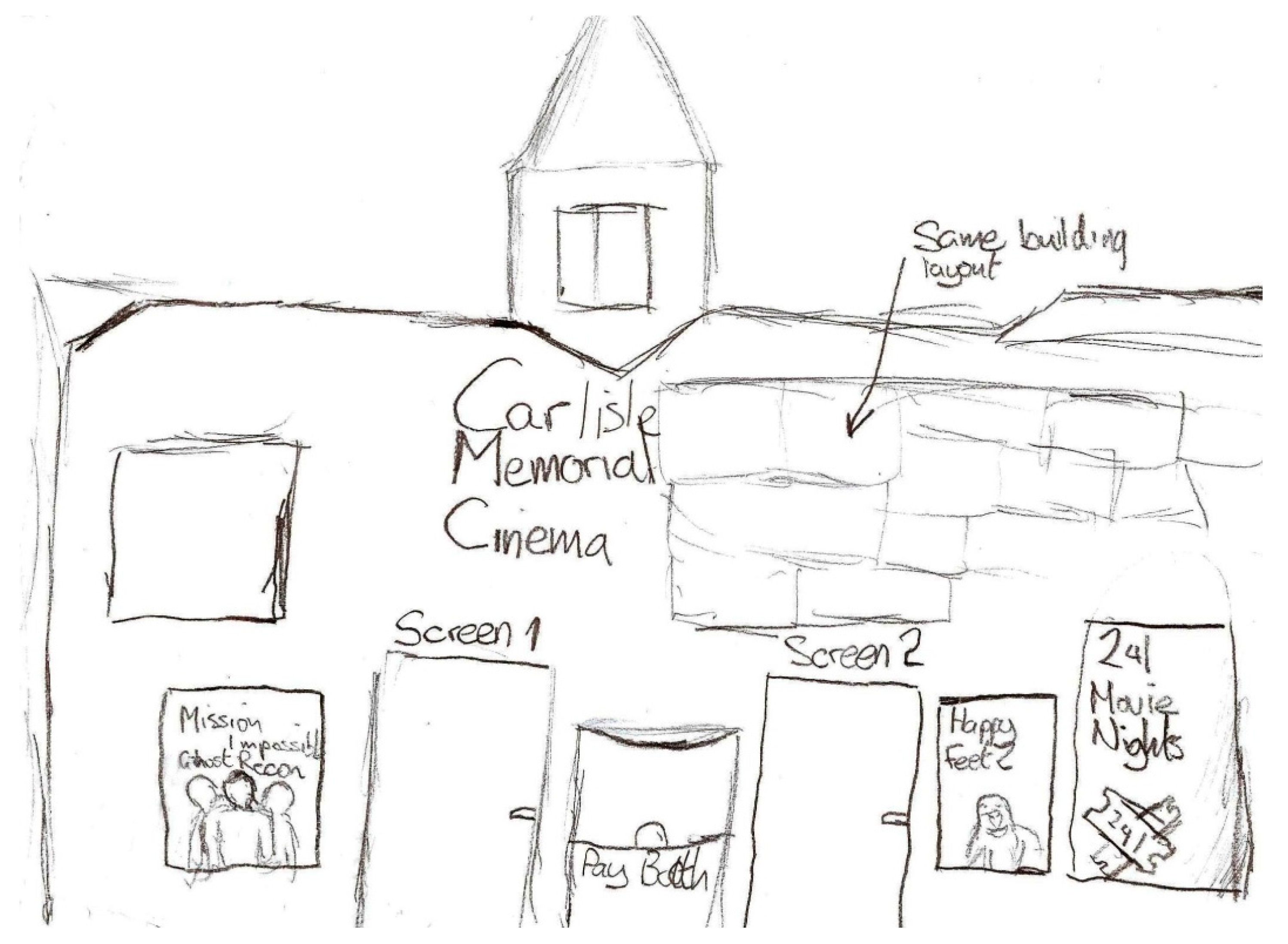

In total, 106 children aged between 11–14 took part in five workshops held during November and December 2011. The workshops encompassed visual, oral and audio processes set out in four key stages; Firstly; the young people were asked to complete a questionnaire which focused on their age, religion and local residential area. Secondly; the participations were asked to draw their expectations of a typical church building as they remembered or imagined it to look like. Thirdly; the youths were then asked a series of questions regarding their opinions and knowledge of Carlisle Memorial Methodist Church. A formal photographic presentation was then provided in which the historical development of the building was discussed with the youth group. Finally, a responsive session was conducted, in which the participants were asked to reflect on the church building and the information they had just viewed. They were then asked to reflect on the future use of the building through drawing.

Drawing was used within the workshops as it has been found that children and young people will often draw that which is important to them, and leave out that which is not (

Butterworth 1977). Drawing is one of the means by which young people express their inner-self and can be interpreted as a method of communication, which is often the case in sociological and psychological research. They draw what they know in their own style and thus their perceptions, emotions, sensibilities, and motor functions, together with the factor of social experience, are all added to the picture that is drawn on the paper (

Kitahara and Matsuishi 2006). By combining the described drawings of the young people and with observations of behaviour and informal interviews conducted throughout the workshops, it was hoped that the techniques would be as youth-friendly as possible, to enable an analysis of the data to be implemented to the highest standard.

4.3. Ethics

The main ethical implications of this research included the consideration of the young people as a vulnerable group and the fact that the project dealt with the difficult issue of religion in Northern Ireland. Methodologies were consulted which dealt with children and sensitive issues such as religion in Northern Ireland. A variety of participatory tools and techniques were adopted during the workshops. These tools are described in the ‘tools for adolescent and youth participation’ document developed by the Commonwealth Youth Programme, and were selected for their ability to generate discussion and to understand particular organisations and identities. The tools selected were aimed at promoting meaningful children’s and young people’s participation and included brainstorming, ice breakers and interactive exercises such as ‘Why Why Why?’ which helped to uncover problems and bring forward solutions to the reuse of the church building (

Commonwealth Youth Programme 2005).

4.4. Data Analysis

The data was analysed through two complementary methods; thematic and descriptive analysis. Regarding their drawings, a section of thematic analysis was dedicated to addressing this evidence purely and objectively as representations of space, through the consideration of the drawings by means of the following themed parameters: overall pattern, drawing method, scale, orientation and certain key points highlighted, in order to contextualize the case study analysis on the basis of representation.

A descriptive statistical analysis approach was then used to examine the questionnaires and workshop discussions. The workshop discussions were divided into two sections; expectations and responsive actions, which were based on a series of questions that the respondents were asked after the presentation relating to the influence of architecture on local identity and the redevelopment potential of this building.

6. Discussions

The key questions considered for this research project related to establishing the role and influence of a disused religious building on youth identity and place attachment, with a view to better understanding the role of youth participation in heritage schemes.

In terms of identity, previous and ongoing research by the

BBT (

2009) established that the highly fractured nature of the area in which Carlisle Memorial Methodist Church is located creates a difficult environment in which to find unanimous community support for any proposed redevelopment project. The BBT study found widespread and deeply held adult community support for the building to be placed at the heart of a heritage-led regeneration effort, but unfortunately a consensus on its reuse was not readily identified. This existing tension suggests that local adult identity is still strongly connected to the building. Interestingly, this study showed that youth identity was less concerned with the buildings previous religious connection in comparison to adult opinions (

BBT 2009). The identity of the building as a Methodist church may have diminished as the building has continued to decay, however space is still clearly perceived in this area as fundamental to the exercise of power. In light of this, the BBT study (

BBT 2009) revealed local communities need to maintain their sense of belonging to the area and the buildings within it. There is no doubt that the proposed re-use of the building must be a neutral solution which can bring equal benefits to all local communities and indeed age groups.

As research is still progressing with regard to the redevelopment of Carlisle Memorial Methodist Church it was felt that investigating youth perception would aid the overall reuse potential of this building and assist in policy development for the reinvention of other historic buildings in Belfast for wider community use. In terms of youth identity and place attachment, this research, although a relatively small study, established that proximity to a building does not necessarily create a stronger connection or association with it from a youth perspective. Participants in this study, regardless of religion, did not consider its previous use relevant when thinking about its redevelopment potential, as it was previously stated that only 6.5% lived in the postcode area of the Church. This is perhaps related to the fact that the participants have only known this building to be ‘disused’ and therefore have limited attachment due to a lack of personal experience of Carlisle Memorial Methodist Church as a functional building. The fact that the church building also houses a minority religion (Indian Community Centre) and is located next to an Orange lodge office (a symbol closely associated with Unionism and Loyalism in Northern Ireland) did not appear to influence youth considerations of the re-use options for this building. Despite previous studies by

McPhillips and Russell (

2011) highlighting that local youths in Belfast have a limited knowledge of minority religions, the location of the Indian community centre and Orange lodge were welcomed and from a youth perspective posed no threat or raised any issue regarding re-use.

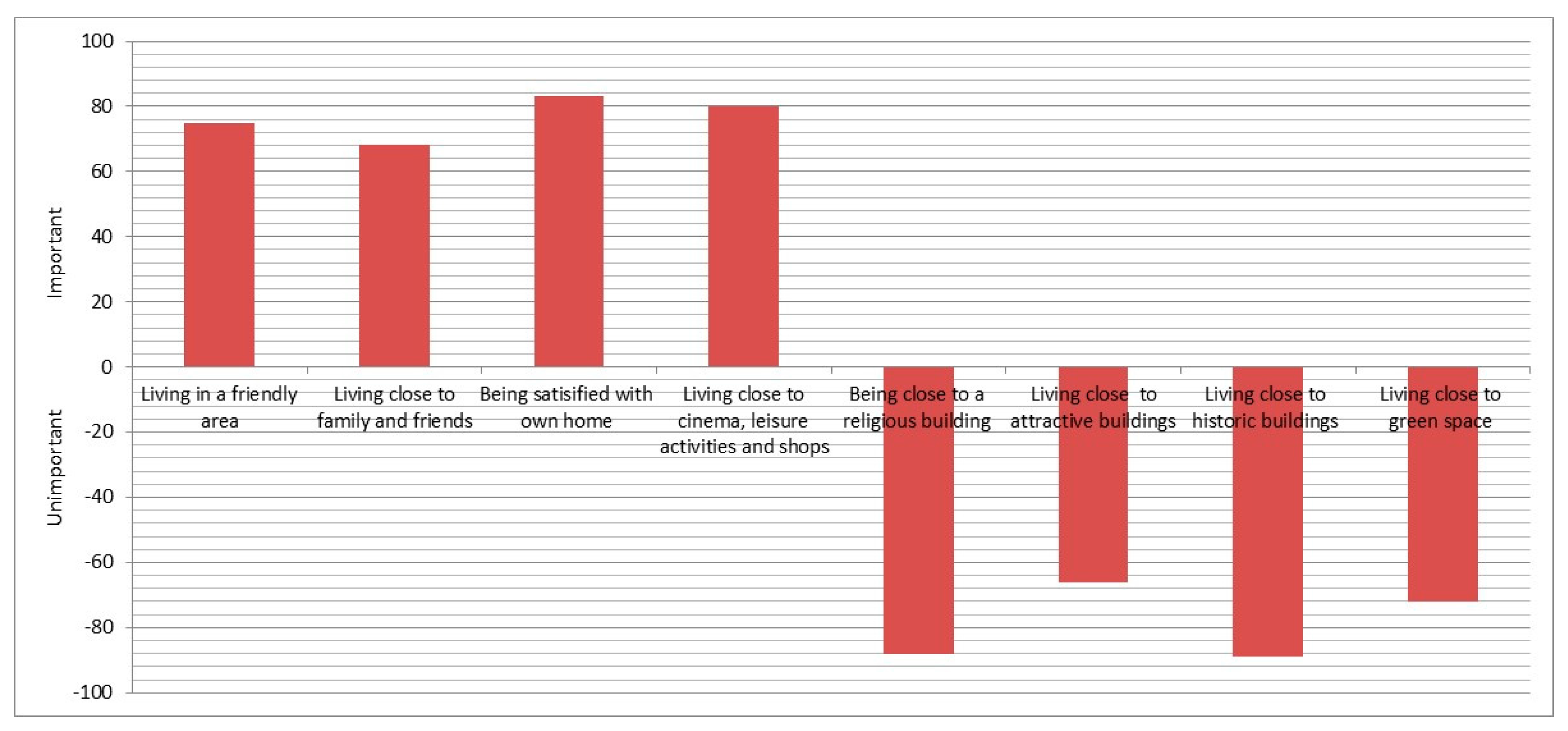

With reference to young people’s associations with the built environment in a more general context, findings suggested that unless youth already had a well-developed relationship with a church building, they did not consider it to be a necessary part of what makes a good place to live. Instead, they identified friendliness of their area, being satisfied with their own homes and proximity to leisure activities, cinemas and shops as being more important. The study also demonstrated that the youth felt that it was more important to live somewhere attractive rather than historic. What they considered to be attractive in the built environment was not questioned further during the workshops; however, it was evident that ‘historic buildings’ are not necessarily considered attractive. The term ‘old building’ was generally used in discussions during the workshops by the youth participants in a negative context whereas the terms ‘modern or new building’ appeared to be favoured more positively. Due to time restrictions discussions did not develop these terms further, however it was clear that a more modern building was associated with materials such as glass.

Another interesting finding was that living close to green space was classified as unimportant by 72% of participants. No links were established between proximity to the building and satisfaction with the living area. The majority of respondents felt satisfied with the area in which they lived, generally classifying the area they lived in as a modern area. It has become clear through the investigation that buildings of importance to this age group are those which provide a function they can respond to such as supermarkets, cinemas, shops and those buildings that provide other leisure-type activities. The study did draw connections with previous research by

McPhillips and Russell (

2011) in terms of the influence of symbology, objects and text. The youth demonstrated a clear understanding of religious symbology through their expectation drawings and attempted to acknowledge and retain some elements of the churches architectural form when considering options for re-use. This finding also aligned with research by

Coeterier (

2002) which showcased that authenticity, details and ornaments are important in the redevelopment of historic buildings.

The history of the church was important to the youths with the majority feeling that the story of its development should be captured in the new use of the building. The story was regarded as interesting and enjoyable. The fact that it was associated with the Methodist faith did not seem to be an issue to any of the youth involved in the workshops in terms of their identity. This suggests that through the story of Carlisle Memorial Methodist Church, the youth developed a curiosity and sympathy with the building’s demise. Unlike previous research by

McPhillips and Russell (

2011) spatial experience was not conducted through a physical walkabout tour of the building, however the revised methodological approach of photographic based-workshops also appeared to provide an effective method for engaging youth in the local built environment. Whilst this study was limited in terms of size and scope, a number of interesting issues have been highlighted for further development. Similar education based workshops would be useful in helping to improve youth engagement with their local environment and connection to other religious and historic buildings. In line with research by

Spennemann (

2006) there is still a need for public education for the next generation, and cultural heritage must have a firm place in the school curriculum. The need for this is also evidenced by the fact that 82% of participants from this study had not visited a historic building within the past year and 78% stated that they did not hold an interest in the history of their area.

In summary, the project has shown that young people have a better attachment to a building when they have had a personal experience or connection to it. When a building is disused this connection is less likely to occur. Youth can, however, develop a connection through an appreciation or understanding of a building’s apologue. They must however be able to connect to the story and in the case of Carlisle Memorial Methodist Church this was possibly achieved through the family-focused story. The knowledge of the local area was limited and interest in local history lacking by the youths involved in the workshops. The youths did however demonstrate a respect for Carlisle Memorial Methodist Church once they connected to its story. This was evidenced through their ‘re-use’ drawings and desire to maintain awareness of the Carlisle family and the building’s history. The youths felt the story would certainly be of interest to local people as well as tourists.

Youth aged 11–14 also appear to connect better to buildings that provide them with a sense of security or entertainment function i.e., home, shops and cinema. Religious buildings are not necessarily considered a key part of what makes an area a good place to live unless that person already has an established relationship with that type of building i.e., regular church attendance. From a youth perspective re-use options for Carlisle Memorial Methodist Church should consider the historical development of the church and incorporate the story of the Carlisle family. The building would serve the community best as a shared multi-functional resource that could be used by adults and young people.