2. Luther and the Jews

Although the Wittenberg

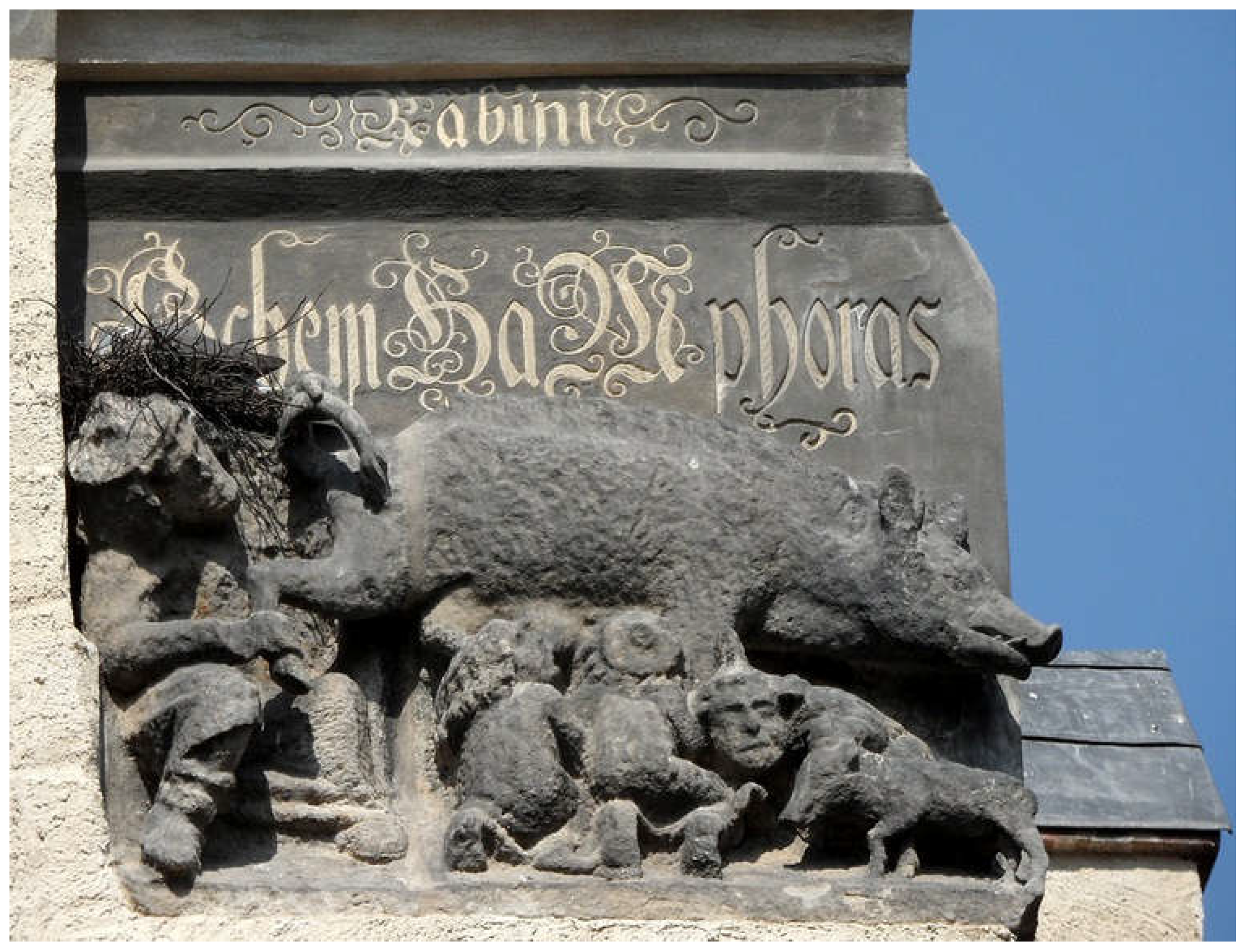

Judensau predated Luther by two centuries, it nevertheless received favorable mention in his 1543 writing

Von Schem Hamphoras (

Of the Unknowable Name):

Here at Wittenberg, in our parish church, there is a sow carved into the stone under which lie young pigs and Jews who are sucking; behind the sow stands a rabbi who is lifting up the right leg of the sow, raises the behind of the sow, bows down and looks with great effort into the Talmud under the sow, as if he wanted to read and see something most difficult and exceptional; no doubt they gained the Shem Hamphoras from that place.

Later followers of Luther took inspiration from his writing and placed an inscription over the relief: “Rabini Shem hamphoras,” a nonsensical name meant to ridicule the medieval Jewish mystical reference to the unspeakable divine name.

Martin Luther’s attitudes toward Jews and Judaism have been the subject of intense scrutiny by historians and others, in terms of both the role those attitudes play in Luther’s broader theology and their place in the history of Western anti-Semitism (

Kaufmann 2006;

Hillerbrand 1990;

Oberman 1984;

Edwards 1983).

3 This scrutiny predated the Second World War and indeed was underway among Luther’s contemporaries and in the period immediately following his death. However, favorable mentions by Nazi propagandists and the move by some to draw a direct line from Luther to Hitler and the Holocaust show the truth of Thomas Kaufmann’s observation that it “would be naïve or careless to think that a German Protestant church historian could approach the extraordinarily complex topic of ‘Martin Luther and the Jews’ without considering the fatal historical effects” of Luther’s writings. At the same time, Kaufmann finds equally problematic the idea that there is a necessary or inevitable connection between the two (

Kaufmann 2006, p. 69).

Complex and problematic: the two terms could also be said to describe the task of instructors assigned to introduce the sixteenth-century reformer to undergraduate students. One of the first questions to arise is that of texts: out of the vast corpus of Luther’s writings, which should claim a spot in the limited real estate of course syllabi? Luther’s attitudes concerning Jews are frequently summarized by dividing them into two periods, earlier and later, that span the majority of his writing career. The earlier period may be represented by the 1523 treatise

That Jesus Christ Was Born a Jew. Writing not long after his excommunication by Leo X, Luther used the unbelief of the Jews as a cudgel against the Catholic Church: “If I had been a Jew and had seen such dolts and blockheads govern and teach the Christian faith, I would sooner have become a hog than a Christian” (

Luther 1962, p. 200). He goes on to encourage a welcoming attitude toward Jews in order to facilitate their conversion. But two decades hence, Luther had seemingly performed a complete about-face. In the more frequently cited and taught

4 On the Jews and Their Lies (1543), he advocated burning Jewish synagogues and homes, confiscating Jewish property, forbidding rabbis to preach, and removing travel protections. The reasons for his change continue to be debated, while the work stands as one of the most explicit anti-Semitic statements of the Reformation era, a period that had no lack of vitriol. How might these two works be put to work in the classroom, and what might be made of their apparent contrast? The historical circumstances and contents of each warrant closer attention.

The occasion of Luther’s first major writing about Jews,

That Jesus Christ Was Born a Jew, was the quashing of rumors being circulated by his enemies, namely that Luther taught that Jesus was the natural son of Joseph and that Mary was not a virgin. From a pedagogical standpoint, it is useful to note that here Luther was not so much speaking

to Jews as

about them; his primary audience was a Christian one and the occasion of the writing was a dispute among Christians. As was often the case, Luther turned the tables on his opponents by taking what could have been a purely defensive moment and adapting it to his own purposes. In the first part of the treatise he succinctly refuted the charges against him and argued that Jesus was a descendent of Abraham through his mother Mary, a virgin. He did so to refute his detractors but, more important, he also claimed that his argument “might perhaps win some Jews to the Christian faith.” In Luther’s estimation, Jews had every reason to reject Christianity: they had been treated as “dogs rather than human beings” and suffered loss of property. Even those who had been baptized had been exposed to a false Christianity that was “mere babble without reliance on Scripture.” In sum, Luther understood the experience of Jews up until his day as one of maltreatment and sometimes coerced inclusion in a soulless faith (

Luther 1962, p. 200).

After thus indicting his critics, Luther ostensibly switched audiences and attempted in the second part of the treatise to persuade Jews that Jesus is the true messiah. It is worth pausing here with students to note the role of text and subtext, that is, to consider whether Luther was primarily making a positive argument to convert Jews, or simply continuing to use the example of the Jews to berate his Catholic opponents. For Luther the case hinged on the proper interpretation of Scripture. For instance, in Genesis 49 when the patriarch Jacob says “the scepter shall not depart from Judah, nor a teacher from those at his feet, until the Shiloh comes,” historical circumstances necessitated, he averred, that this could only be a reference to Jesus; or, in Daniel 9 Luther argued the text can only refer to the destruction of the temple by the Romans, which led to the conclusion that Jesus is the true messiah, and so on. Here we see Luther the controversialist has given way to Luther the professor of biblical exegesis, although the roles are certainly intermeshed and never truly separable. The assumption that appears to power the argument throughout is that good, historically grounded exegesis should win the day and persuade Jews who have suffered abuse by Catholics. In this spirit, Luther concluded with an uplifting admonition:

Therefore, I would request and advise that one deal gently with them and instruct them from Scripture; then some of them may come along. Instead of this we are trying only to drive them by force, slandering them, accusing them of having Christian blood if they don’t stink, and I know not what other foolishness. So long as we thus treat them like dogs, how can we expect to work any good among them? Again, when we forbid them to labor and do business and have human fellowship with us, thereby forcing them into usury, how is that supposed to do them any good? If we really want to help them we must be guided in our dealings with them not by papal law but by the law of Christian love. We must receive them cordially, and permit them to trade and work with us, that they may have occasion and opportunity to associate with us, hear our Christian teaching, and witness our Christian life. If some of them should prove stiff-necked, what of it? After all we are not all good Christians either.

Several points are worth noting here: (1) Luther rooted his positive stance toward the Jews and the basis of his criticism of Catholics in his evangelical intent; (2) the means of that evangelism should be the proper discernment of the true meaning of Scripture; (3) particularly notable given his later writings, Luther drew a connection between socio-economic oppression, the Christian ethic of love, and Jews’ receptiveness to the gospel; and (4) he tempered his optimism and acknowledged many will resist.

For many historians the latter point is the key to finding continuity among Luther’s various writings about the Jews despite their apparent contradictory perspectives. Indeed, two decades later, Luther’s optimism about the conversion of Jews exposed to the true gospel had evaporated, to be replaced with a thoroughgoing hostility.

On the Jews and Their Lies (1543) shocked not only his opponents but many of his colleagues as well with the vehemence of its rhetoric and the extent of the recommended strictures to be leveled against Jews. He repeated the well-worn and fantastical medieval charges that Jews poison wells, kidnap children, drink their blood, and desecrate the host. Based on the guilt of the Jews, Christians were “not at fault in slaying them.” Rather than decrying the ill treatment of Jews as he had two decades earlier, Luther now understood it as the “terrible wrath of God these people have incurred and still incur without ceasing” (

Luther 1971, p. 267). Given that anti-Semitic violence was now thought to have the divine imprimatur, Luther proceeded to instruct the magistrates on a number of punitive measures which may be roughly divided between the religious and the economic. First, the burning of synagogues and schools, as well as seizure of books and other materials, was to be done in the name of suppressing blasphemy. These measures appear to have stemmed from Luther’s frustration with the lack of Jewish converts to Lutheran Christianity as well as rumors that Jews were attempting to convert Christians to Judaism. Alongside these religious strictures, a variety of other measures were directed at constricting Jewish economic and social activity and influence. Homes were to be burnt so that Jews would remember “they are not masters in our country, as they boast.” Safe conduct was to be abolished, given they had no business in the countryside “since they are not lords, officials, tradesmen, or the like.” Additionally, confiscated wealth would be used to reward Jews who did convert, and Jews would be put to work in the fields since it was not fitting they idle away their time by “boasting blasphemously of their lordship over the Christians by means of our sweat” (

Luther 1971, pp. 269, 270, 272). Taken together, the economic focus of these recommendations indicate a profound unease with the very presence of Jews in the midst of Christians and resentment at what economic space was allowed to them.

Historians have suggested a variety of reasons for Luther’s apparent shift—ill health, negative encounters with Jews, rumors of Jews converting Christians—but if we place the latter work in context the contrast begins to diminish. Luther, believing he was living in the last days, saw the enemies of Christ coalescing around him: the Jews joined papists, Turks, Anabaptists, and others as those who impeded the spread of the gospel and thus exposed themselves to the final, wrathful judgment of God. In Luther’s mind, the Jews’ evangelical moment seemed to have passed, and he channeled what he believed was the divine disgust, using the most vituperative language he had at hand. Thus, in this context one might conclude that Luther’s shift is one of style, not substance (

Oberman 1984, pp. 113–17).

While historical contextualization may go a way toward the first goal of introducing students to the world in which Luther wrote, we still must consider the weight of these texts as they come into our own age and classrooms. One useful approach is to locate the anti-Semitism of the early modern era against the larger backdrop of processes by which societies established boundaries and maintained social control through the identification of the “Other,” any group that existed on the margins and had little social and economic power to resist societal persecution (

Moore 2007).

5 Toward this end, Hans Hillerbrand juxtaposed the Jews alongside Anabaptists, witches, beggars, and prostitutes as a way of considering the fate of the “Other” in the Reformation (

Hillerbrand 1998). Hillerbrand argued that what was at work was the ability of society—defined here as “those exercising political power...to control, or intellectual power...to create consciousness”—to prescribe value judgments about difference, and crucially, to make those differences visible (

Hillerbrand 1998).

6 If difference per se is not the defining characteristic of the “Other” in society but instead it is when difference is defined as deviance that the “Other” comes into focus, then the question that naturally follows is “toward what end?” In his landmark study

Orientalism, Edward Said examined the essential role that the construction of the Orient played for the formation of Western identity. The East provided an alternative “self” that in comparison to the West was judged to be inferior (

Said 1978). Returning to Luther, we can see how, for example, this meant that Jewish exegesis of the Scriptures could not simply be an alternative reading; it must be wrong, or more precisely, diabolically wrong, for Luther’s Christian reading of the Old Testament to be correct. Also, in this context Luther’s recommendation of economic restrictions for Jews becomes more closely aligned with his claim of exegetical superiority: Jews were to remember that “they are not masters in our country” (

Luther 1971, p. 269), a territory one might define theologically as much as geographically.

It perhaps should not go without saying that using this interpretative lens need not equate to ascribing motive or intent to Luther or any other actor in the sixteenth century. That is to say, it is possible, indeed advisable, first to locate Luther’s writings in the context of sixteenth-century debates over biblical and theological interpretation. Luther did not know the “Other”; he knew only the diabolically inspired forces aligned against the gospel, forces to be resisted through the correct reading of the Scriptures (

Oberman 1989). Yet the pedagogical task necessarily extends beyond the past into the present in the context of the classroom, where students encounter texts and ideas and understand them through their own interpretative contexts, and crucially, they do so in the presence of other students who may or may not share their contexts. Establishing a productive intersection of these multiple interpretative frameworks is the crucial work of reading texts in the community of the classroom. We will have more to say about this key challenge faced by teachers after we consider a second case study.

3. Bach and the Jews

Two centuries after Luther, in his first year in Leipzig (1724), J. S. Bach composed the

St. John Passion on a libretto from the Luther Bible’s translation of John’s gospel. Fast-forwarding to April 1995, a performance of the

St. John Passion was scheduled for Parents’ Weekend at Swarthmore College in Philadelphia. Several students who were members of the choir refused to perform because they viewed the work as anti-Semitic. Swarthmore, a Quaker institution, did go through with the performance, and on Palm Sunday, but contextualized it with discussions, program notes, and symbolic empty chairs in the chorus. In the summer of the same year, the Oregon Bach Festival planned a performance of the

St. John Passion as part of an observance of the fiftieth anniversary of World War II, again eliciting negative reactions. In response, the Festival added discussions, an ecumenical religious service, and Jewish works to the schedule. These incidents set off a national musicological controversy and evolved into a ripe teachable moment for Bach scholar Michael Marissen, who had been a Swarthmore professor since 1989. Shortly afterward, Marissen published the thorough and thoughtful study

Lutheranism, Anti-Judaism, and Bach’s St. John Passion, which interprets the historical context of Bach’s passion for today’s listeners and performers (

Marissen 1998;

Marissen 2016;

Belfer 2016).

7The text Bach used for the

St. John Passion consists of passages taken directly from Luther’s translation of John 18 and 19, along with eighteenth-century poetic commentaries. The compiler of this libretto is unknown. This text specifically identifies the people who taunt Jesus and cry out for his crucifixion not as the “crowd” or “mob” but as the “Jews,” and Bach’s musical setting is equally as vivid and dramatic as the text. This is the aspect of the passion that has most distressed modern listeners. Jewish composer and conductor Lukas Foss, who escaped to the United States from Nazi Germany in 1937, began substituting the word “Leute,” or “people,” for “Jüden” in his performances of the passion, and other twentieth-century conductors followed suit (

Lydon 2015).

8 In 2000 when the Oregon Bach Festival reprised their performance of the passion and again held discussions about its anti-Semitism, Marissen and other panelists reached the consensus that open dialogue was better than censoring or changing the work. Everyone does not share this opinion, however. A controversial 2012 Berlin cathedral performance of the passion replaced some of the original text with lines from Jewish and Muslim poetry and liturgy translated into German (

Da Fonseca-Wollheim 2012).

To understand what sparked the controversies, it is helpful to hear an example. Listen to the Vienna choirboys sing “

Kreuzige, kreuzige!” at about 58:00 in this 1985 performance of the

St. John Passion conducted by Nikolaus Harnoncourt (

Harnoncourt 2015)

9

This example illustrates the reason musical passion settings exist in the first place: it is one thing to read in John’s gospel that the crowd yelled, “Crucify him,” but it is quite another to hear the episode in Bach’s striking rendition. In Leipzig Bach was considered a musical preacher, and part of his job was to exhort the faithful to greater devotion. Both he and the Lutheran Church understood the power music has to stir the heart, and the central impetus behind Bach’s church music was to wield that power toward specific ministerial purposes. For Michael Marissen, these pastoral purposes are the key to understanding the

St. John Passion. While Bach’s music does nothing to soften the negative portrayal of the Jews that is already present in the gospel of John, the passion’s greater concern is to convict Bach’s Lutheran contemporaries of their sin and draw them to repentance. Marissen also pointed out that compared with the passion settings of other Baroque composers such as Handel and Telemann, Bach’s

St. John Passion is relatively restrained in its depiction of the Jews (

Marissen 1998, pp. 29–30, 47).

This is not to say, however, that there is no anti-Judaism in Bach. In another study, Marissen considered Cantata 46, which Bach composed for the tenth Sunday after Trinity, also in his first year in Leipzig (1723) (

Marissen 2003;

Marissen 2016).

10 The liturgical focus for this particular Sunday was the historical and spiritual “Israel.” Sermons and prayers for that day drew a clear connecting line, starting with the destruction of Jerusalem by the Babylonians in the sixth century B.C.E., continuing through the Jews’ rejection of Jesus as the Messiah, and ending with the destruction of Jerusalem by the Romans in 70 C.E. The gospel reading was Luke 19:41–48, in which Jesus weeps over Jerusalem and then drives the money-changers out of the Temple. In the vespers service on the tenth Sunday after Trinity, the epistle reading was replaced by the story of the Roman destruction of Jerusalem, as told by first-century historian Josephus. Liturgical music for the day followed suit: a typical motet would be a setting of Psalm 137, “Super flumina Babylonis” (

Terry 1926;

Marissen 2016).

11Bach’s Cantata 46 sits squarely within this established liturgical tradition. The opening chorus is a dissonant, minor, chromatic fugue on the text from Lamentations 1:12: “Behold, yet, and see if any sorrow be like my sorrow, which has struck me. For the Lord has made me full of distress on the day of his fierce wrath” (

Marissen 2016, p. 97). Two pairs of solo movements follow: a tenor recitative and bass aria, and an alto recitative and aria. The tenor compares Jerusalem’s downfall to the Old-Testament destruction of Gomorrah, but claims it would have been better if Jerusalem had been destroyed utterly. Bach used the same melodic interval, a tritone, for “Gomorrah,” “Christ’s enemy,” and the image of God breaking a staff—a symbolic act of final judgment. From Medieval times, the tritone has been considered the harshest interval, and known as the

diabolus en musica. This prominent interval, along with chromatic harmonies, a disjunct vocal line, and key relationships that are incongruous for Bach’s time, creates a harshly accusing tone. The slide trumpet and agitated strings of the bass aria conjure a military scene as the text paints God’s wrath against Israel as a storm, long threatened and finally broken forth. The trumpet constitutes an ancient musical shorthand for battle, and this style of string writing, known as

stile concitato, was in Bach’s time a convention for militant effects. The much gentler alto recitative and aria shift the focus from the Jews, on whom God was believed to have passed final judgment, to Bach’s Lutheran congregants, who could presumably still repent and receive grace. Listen to the musical contrast in this recording conducted by Helmuth Rilling (

Rilling 2011).

The overarching structure of the cantata, then, employs the fate of Israel as an object lesson to convict Lutheran Christians and turn them to repentance. Both the text and Bach’s musical setting serve to elicit a specific spiritual response. To modern ears, however, the harsh portrayal of the Jews and of God’s judgment against them is jarring. Acknowledging such anti-Jewish polemic in Bach’s vocal music has been difficult for the musicological community to reconcile with his foremost status among composers, and among composers of Christian music to boot. However, the controversy has fruitful teaching applications.

For music students, it can be a case study for examining how music takes on extra-musical significance. Consider the various and complex ways music and text interrelate in Cantata 46. The liturgical context, biblical context, and musical context all carry associations. Leipzig churchgoers would have heard Bach’s cantata alongside other liturgical elements connecting God’s judgment against the Jews with their rejection of Jesus and with biblical passages expressing God’s wrath. They would have heard the trumpet and stile concitato strings as militaristic but interweaving recorders as a gentle lament. They would have heard the dissonance of the tritone, which also held symbolic significance at a deeper analytical level for contemporary musicians. Somewhat more abstract is Bach’s use of canonic imitation in the opening chorus—a device he frequently employed as a musical pun when setting texts having to do with law, since “canon” literally means “rule” or “law.”

Even more arcane, yet still salient, are the cantata’s harmonic relationships. Bach scholar Eric Chafe has detailed how Bach and his predecessors and contemporaries used anabasis, or modulation to keys with more sharps, and catabasis, or modulation to keys with more flats, to set texts with positive and negative themes, respectively (

Chafe 1991;

Chafe 2000). Marissen has pointed out a “bizarre tonal fracture” and “striking harmonic catabasis” in the opening chorus of Cantata 46, a “harmonic breach” Marissen interpreted as an image of destruction, “aptly reflecting the chorus’s biblical lines concerning the Lord’s fierce wrath against the city of Jerusalem” (

Marissen 2016, p. 97). These key relationships may be inaudible to all but the most musically sophisticated listeners, and the extra-musical associations they carry are made even more complex by the fact that thinking of harmonic modulation as either “upward” or “downward,” as Chafe does, is in itself a metaphor (

Lakoff and Johnson [1980] 2003;

Schulenberg 1995). Nevertheless, harmonic modulation was certainly significant for Bach, the most sophisticated of musicians, composing in conversation with others who spoke a similar musical language.

This is why it makes sense to resist the temptation to view Bach’s music as pure music without inherent extra-musical meaning. Such a view is attractive, especially to musicians for whom musical meaning is paramount. However, the concept of music as an entity unto itself developed in music aesthetics only at the beginning of the nineteenth century, and even then only applied to instrumental music (

Bonds 1997). While the nineteenth and twentieth centuries saw no shortage of scholars who read even Bach’s vocal music from this absolute point of view, the approach is anachronistic and unhistorical (

Taruskin 1995;

Marissen 2016).

12Or, to be more accurate, this approach is rooted in its own historical and cultural context (

McGinnis 2006).

13 Early Bach studies grew out of debates over the status of instrumental music. Turn-of-the-nineteenth-century critics such as E. T. A. Hoffmann proposed that instrumental music could, through its sheer form and structure, reflect and even manifest the forms of a neo-Platonic ideal realm, and Bach’s nineteenth-century biographer Philipp Spitta extended this claim to Bach’s vocal church music (

Spitta 1951). Spitta established a chronology of Bach’s works using watermark and handwriting evidence, then drew conclusions about Bach’s development as a composer based on this chronology. In Spitta’s view, Bach became increasingly careful over the course of his career to preserve the integrity of the Lutheran chorale tune, so that his “later” cantatas only surround and adorn the chorales without changing them substantially. For Spitta, this meant Bach’s church cantatas adhered increasingly more closely to the chorale tunes and therefore increasingly more closely to the “objective” truth the chorales carried. As such, Bach’s late church cantatas reflected a realm of philosophical truth otherwise accessible through strictly instrumental music but not vocal.

Spitta’s chronology and the conclusions he drew from it remained unshaken until the mid-1950s, when Alfred Dürr and Georg von Dadelsen proposed a new chronology that combined liturgical information with watermark and handwriting evidence (

Herz 1985;

Kerman 1985).

14 By then, both music and musicology were playing on the field of mid-century modernism and using the languages of math and science in the service of rational inquiry (

McGinnis 2003).

15 The atmosphere was much more skeptical and secular, and biographers less prone to hagiography than in Spitta’s time. Dürr’s and Dadelsen’s (now classic) revised chronology called into question Spitta’s teleological interpretation of Bach’s career, and consequently his characterization of Bach as devout Lutheran.

Furthermore, as the rise of the historical performance movement in the late twentieth century saw an accompanying uptick in the number of studies focusing on the historical, liturgical, and theological contexts of Bach’s music, (

Kerman 1985)

16 other scholars countered with the aesthetic point of view that Bach’s texts and religious contexts are tangential to a true understanding of his music as great art (

Schulenberg 1995).

17 It is certainly tempting to take this aesthetic approach when confronted with offensive material such as anti-Jewish polemic in Bach’s music, to ignore text and context and concentrate rather on the sheer magnificence of the music itself. Could not Bach’s music be even more relevant if we interpret it in light of our own worldview, giving him a pass when the values of his society conflict with those of our own?

To do so, however, is to miss the benefit of learning from history, and to miss out on the power art has not only to entertain but to edify. If Bach, who was not only intellectually brilliant but also deeply devout, composed anti-Jewish music, we understand both the composer and his works better if we investigate the circumstances. More important, we hone our own moral sense when we put ourselves in Bach’s place: a pastoral musician employing the most effective rhetoric he can to lead his flock to the salvation of their souls. When we face up to history’s low points as well as the high ones, we can become better and more ethical as individuals and societies. What blind spots do we ourselves have, we might ask, that might become evident three centuries from now?

4. Conclusions

Earlier we suggested that the educator’s task with regard to objectionable material is twofold: (1) provide a proper historical context in which to understand the work and (2) provide space for students to consider and address the ethical questions that arise from the study of such works. Furthermore, we suggested that to do one without the other is to fail. If we merely stand in judgment against the ethical failings of past actors without seeking to understand the context that gave rise to them, we risk missing the lessons of history—seeing the habits of thought, speech, and action that culminate in unethical conduct. That is, we fail to learn from history. At the opposite extreme, to become trapped in the past, as it were, in our consideration of works such as On the Jews and Their Lies and Cantata 46 without bringing the question forward risks ignoring how past thought might link to present attitude and action.

As an example of this, consider a distinction that emerges regularly in the secondary historical literature, that is, the distinction drawn between anti-Judaism and anti-Semitism. Different scholars attach various nuances to the terms, some quite strictly, but the former is usually taken to refer to opposition to Jewish theological positions and especially exegetical strategies regarding the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament. In contrast, the latter term denotes opposition to, or worse, hatred of Jews as a people. This hatred plays on vile racial stereotypes and conspiracy theories, frequently justifies violence and persecution, and is understood by many to have its origins in racial theories of the nineteenth century. This distinction, while valid in historical analysis and useful in certain contexts, nevertheless carries risks as well, inasmuch as it may downplay or ignore potential connections between theology and violent action. Put succinctly, religious ideas have social consequences (

Geertz 1973;

Oberman 1984).

18 In the context of the classroom, a risk teachers face is the inclination of students and perhaps teachers themselves to contain objectionable ideas of Luther, Bach, and others within the bounds of theological discourse or music aesthetics—the world of ideas. Instead, teachers of history can help students make the connections between ideas and actions in the past, identify patterns that recur in history, and make judgments based on their interpretations of the evidence at hand. But should the work end there? Indeed, can it?

In a recent class at our university we explored how music can help construct identities—of self and “Other”—that either reinforce or challenge societal norms. Our topic was the racist portrayals of African Americans in nineteenth-century black minstrel shows, and before confronting these portrayals the class laid down ground rules for discussion. Through these rules or guiding principles the students recognized that racism is not only part of our common history but also a thread running through our present discourse. As we prepared for our class discussion, they predicted that studying this issue in a historical context would help us think more clearly in our own. In the case of the minstrel shows, we found that the shows’ portrayal of black slaves served particular functions in nineteenth-century American society: primarily, to reinforce social norms by characterizing slaves as dimwitted, happy-go-lucky, and content with life. This characterization of an “Other” by society’s powerful served in part to uphold the institution of slavery, and it met subtle and creative challenges in the slaves’ own minstrel shows and in parodic genres such as the cakewalk. These layers of portrayal constituted acts of social positioning in much the same way that Luther positioned himself against Catholicism via his portrayal of the Jews, or Bach set the Jews up as an object lesson for his Lutheran congregants. As our class came to understand each portrayal as either supportive or subversive to the dominant systems of society, we also began to turn the lens to our own society, and to question the function of the identities we construct.

William Faulkner famously wrote “The past is never dead. It’s not even past” (

Faulkner 1975). There is no better lens for understanding the present than careful reading of the past. When we introduce difficult texts and ideas into the classroom, students inevitably make moral judgments. Recognizing that fact and bringing those judgments into the discourse of the classroom is the hard work of education, not without risk, but rich with potential benefits for all.