Abstract

In recent years, authorities in mainland China have renewed their call for the sinicization of Christianity through theological discourse. Given that Christianity is largely expressed in visible, worship-based ways, such as music (songs), rhetoric (sermons), rituals (sacraments), symbols (crosses, garments, banners, etc.), posture and gesture (genuflecting, lifting hands, etc.), one wonders at the implication of this development. Might there be an alternative approach to sinicization? This essay seeks to investigate the feasibility of sinicized Christianity from the ontology of musicking as purveyed through the practice of congregational song.

Keywords:

China; Asian; theology; worship; musicking; ideoscape; mediascape; congregational song; sinicization; contextualization Christianity now makes up the largest single civil society grouping in China.The party sees that.Terence HallidayCo-director, Center for Law and Globalizationat the American Bar Foundation [1]

Since the mid-20th century, Christianity in China has strived to be self-sustaining. Like other Asian Christianities, this shift is visible in its governance, financing, and ministry. For the Three-Self Patriotic Movement of the Protestant Church in China (TSPM), the government-sanctioned national church in the land, this aspiration is enshrined in its three-fold principle of self-government, self-support, and self-propagation. In recent years, mainland Chinese authorities have renewed the call for the sinicization of Christianity with greater urgency. In his speech at the 60th anniversary of the founding of the National Committee of the Three-Self Patriotic Movement of the Protestant Church in China, Wang Zuoan, Director of the State Administration for Religious Affairs, said, “The construction of Chinese Christian theology should adapt to China's national condition and integrate with Chinese culture” [2]. This effort clearly aims for Christian theological thought to serve the nation’s interest as proposed by the ruling party.

While mainland Chinese authorities have sought to sinicize the faith through redressing theological thought, I contend that this approach is inappropriate as it presumes Christianity to be an ideological construct. In challenging this assumption, I suggest that Christianity is a narrative of God’s acts that can be mediated through mediascape, given the latter’s tendency for narrative-based and imagery-rich construction. In turn, I propose that music-making (or musicking), rather than theological thought, is better suited to the task of sinicization as the former is an intrinsic part of Christianity. Through the process of music contextualization, music’s ability for meaning-making is unmistakable even as its three song types serve as suitable markers of the process. My proposal enables the sinicization protocol to be apolitical while enabling Christianity to retain its organic development without politico-ideological intervention. I assert that this is an important consideration in the current geo-political climate of mainland China.

From my perspective, the approach of sinicization adopted by the Chinese authorities bespeaks their perception of Christianity as a rival in the ideological landscape, or “ideoscape”1 [3]. According to socio-cultural anthropologist Arjun Appadurai, who conceptualized this theory on global cultural exchanges, ideoscapes are “often directly political and frequently have to do with the ideologies of the states and the counter-ideologies of movements explicitly oriented to capturing state power or a piece of it” ([3], p. 299). Purdue University sociologist Fenggang Yang, an expert on mainland Chinese politics, remarked, “Since the 1990s, the Communist Party-State has affirmed that religion could have both positive and negative social functions. It may contribute to society through charity services as well as teachings that provide spiritual solace and moral guidance to ordinary people. Nonetheless, religion is the opium of the people that may lead people to anti-social beliefs and may be used by adversary forces for political causes” [4]. Admittedly, some strands of Christianity might harbor such ideals just as other religions do, but I contend that this is not the faith’s primal purpose. Rather, contemporary Chinese Christianity has a strong pietistic focus. This nuance was also observed by Yang, who remarked,

The perspectives of faith communities on the role of religion are of course different from that of the Party-State. Although different religions have different perspectives, overall they believe that religious faith is beneficial to individual believers and society by providing a moral basis for society and moral guidance to individuals.[4]

This outlook is preoccupied with the worship of God through ethical lived experience, which is signified and expressed through various means, such as music (songs), rhetoric (sermons), rituals (sacraments), symbols (crosses, garments, banners, etc.), posture and gesture (genuflecting, lifting hands, etc.), as well as acts of social justice. Extrapolating from Appaduri’s 5~scapes concept, Christianity’s essence and its liturgical acts that encapsulate the pietistic fervor of believers appear to be operating outside the realm of the ideoscape. They seem to fit better in the mediascape realm, particularly in the light of Christianity’s teleology for God’s realm. Appaduri delineated,

Mediascapes whether produced by private or state interests, tend to be image-centered, narrative-based accounts of strips of reality, and what they offer to those who experience and transform them is a series of elements (such as characters, plots and textual forms) out of which scripts can be formed of imagined lives, their own as well as those of others living in other places. These scripts can and do get disaggregated into complex sets of metaphors by which people live as they help to constitute narratives of the ‘other’ and proto-narratives of possible lives, fantasies which could become prologemena to the desire for acquisition and movement.([3], p. 299)

To evaluate this hypothesis, I make use of church musicking as an instrument of mediascape in this investigation, drawing on its ability to form temporal community. Specifically, I propose that the process of contextualization in Asian Church Music would be an appropriate system for this study. Loh developed this approach for church music, which I subsequently expanded ([5,6,7]). In this approach, music is not viewed solely as an object—a sonic phenomenon—but, through its non-musical properties that embody the community, in the sense that “we are what we sing2” [8]. The contextualization approach is mindful of music’s intangible nature. In Music as Discourse, Kofi Agawu, citing Jean Molino, offered insight on this matter. He noted,

The phenomenon of music, like that of language or that of religion, cannot be defined or described correctly unless we take account of its threefold mode of existence—as an arbitrarily isolated object, as something produced and as something perceived. It is on these three dimensions that the specificity of the symbolic largely rests.[9,10]

Equally helpful for our investigation is Christopher Small’s concept of musicking, where music (the sonic phenomenon) “is not a thing but an activity” ([11], p. 2). As an activity, musicking speaks of an encounter-based relationship that gives rise to community meaning-making and a community’s definition of itself. Its efficacy is not the notation artifact but “in action, in what people do” ([11], p. 8). Musicking is action: its investigation calls for a descriptive rather than a prescriptive approach when examining this activity ([11], p. 9). Musicking’s purpose is to understand the meaning of music-making in a specific context and community. Small explains, “Using the concept of musicking as human encounter, we can ask the wider and more interesting question. What does it mean when this performance (of this work) takes place at this time, in this place, with these participants?” ([11], p. 10)

1. The Agency of Musicking in Christianity

Music has always been integral to the Christian faith. The Book of Psalms and various canticles with their roots in the Jewish tradition constitute an important musical repository for Christianity. In fact, efforts to craft songs to articulate one’s faith encounter, or that of the faith community, continue today. While good rhetoric might be effective in convincing a person rationally, it is musicking that captures and nourishes the heart of a person, while serving as a pathway to an encounter with God. In the New Testament, St. Paul the Apostle offered Christians these instructions:

Do not get drunk with wine, for that is debauchery; but be filled with the Spirit, as you sing psalms and hymns and spiritual songs among yourselves, singing and making melody to the Lord in your hearts, giving thanks to God the Father at all times and for everything in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ.(Ephesians 5:18–20, NRSV)

Let the word of Christ dwell in you richly; teach and admonish one another in all wisdom; and with gratitude in your hearts sing psalms, hymns, and spiritual songs to God. And whatever you do, in word or deed, do everything in the name of the Lord Jesus, giving thanks to God the Father through him.(Colossians 3:16–17, NRSV)

From the perspective of Martin Luther, “Music is not an inventio, a work of humankind, but a creatura, a work of God…Next to the Word of God, music deserves the highest praise. She is a mistress and governess (domina et gubernatrix) of those human emotions ([12], p. 373)…which as masters govern men or more often overwhelm them. No greater commendation than this can be found—at least not by us” ([12], p. 371). These, and other theological statements on music that Luther made in his writing, are not arbitrary musings. According to Reformation scholar Robin Leaver, it is precisely Luther’s writing on music as found in various loci that demonstrates how “for Luther the closeness of music to theology was not just a pithy saying but essential to his theological methodology. For him music provided a hermeneutic by which fundamental theology was to be expounded such as when he is speaking about Trinity or when dealing with the distinction between Law and Gospel” ([13], pp. 100–1).

Notwithstanding Jean Calvin’s different attitude about musical instruments in corporate worship, the creation and use of metrical psalmody also attests to musicking as a relevant medium for the worship of God. For Calvin, congregational singing is a means of theological formation, not unlike other rhetorical forms. The Wesley brothers, John and Charles, had a similar understanding of the role of hymns in embodying theology and Christian formation. They stoked the spiritual fervor of England through their hymns. In his study of the lyrical theology of Charles Wesley, United Methodist scholar S. T. Kimbrough posited the properties of lyric, noting,

Its words, rhythm, and stylistic characteristics are made for the ear, lips, body, and senses. Lyrical theology is therefore an experience. This is in part why it can be world-making, for it elicits response. Sentence structure, parallelism, rhetoric, etc. become a song on the lips, in the heart, in one’s life…lyrical theology does not make theology a mere object of consciousness. It engages the forces that shape worship and life.([14], pp. 15–16)

Musicking also has a role to play in locating the identity of the faith community. Albert van den Heuvel, in the preface for an ecumenical songbook, Risk, understood this non-musical function of song when he wrote,

It is the hymns, repeated over and over again, which form the container of much of our faith. They are probably in our age the only confessional documents which we learn by heart. As such, they have taken the place of our catechisms...There is ample literature about the great formative influence of the hymns of a tradition on its members. Tell me what you sing, and I’ll tell you who you are!([8], p. 6)

From these historical examples, it is clear that musicking is a means of experiencing Christianity. In that role, it contributes to the faith formation and emotional sustenance of believers as well as the vitality of the faith community. In the process, musicking helps the community and individuals to define themselves in terms of their faith. At the same time, the assured definition of community and individuals gives credibility and efficacy to musicking. It is a mutually dependent relationship.

2. Types of Congregational Song in Musicking

When Western missionaries ventured forth to other lands, they brought along their cultures, which included European musical traditions. Naturally, the newly Christianized populace in these lands imbibed Christianity in its Western cultural form. Ecumenical scholar Daniel T. Niles observed,

The Gospel is like a seed, but when it is sown, the plant that grows up is Christianity. The plant must bear the marks of the seed as well as of the soil. There is only one Gospel, but there are many Christianities, each indigenous to the soil in which it grows. We must resist the attempt of those who would treat the Gospel as manure for the trees that are already growing in the various lands…When you sow the seed of the Gospel in Israel, a plant that can be called Jewish Christianity grows. When you sow it in Rome, a plant of Roman Christianity grows. You sow the Gospel in Great Britain and you get British Christianity. The seed of the Gospel is later brought to America, and a plant grows of American Christianity. Now, when missionaries came to our lands they brought not only the seed of the Gospel, but their own plant of Christianity, flower pot included! So, what we have to do is to break the flowerpot, take out the seed of the Gospel, sow it in our own cultural soil, and let our own version of Christianity grow.[15,16]

Indeed, this potted musical genre remains pervasive in many churches in the Global South. This is the Adopted Song. It is an initial sign of contextualization. By and large, the Adopted Song features imported musical materials to nourish the nascent faith community. Lyrics are translated into the vernacular, and with sustained use an Adopted Song becomes a song sung from the heart for the local populace. Oftentimes, the prevailing presence of this particular type of song provides evidence for the lack of suitable local resources for musicking.

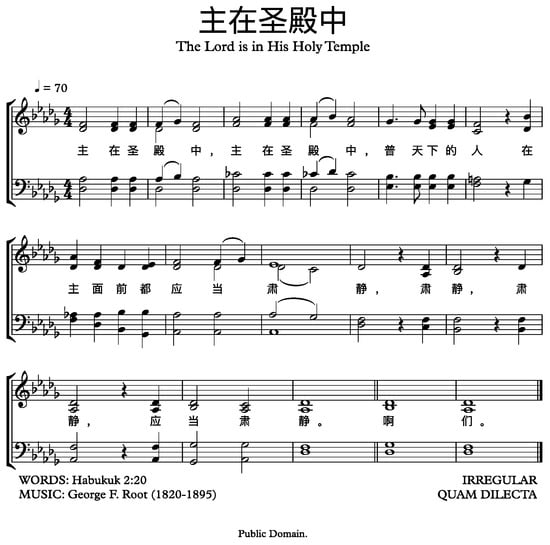

In the context of mainland China, foreign lyrics are translated into Chinese; these translations are matched with the original foreign melody, and then sung. An example of this would be George Root’s “The Lord Is in His Holy Temple (主在圣殿中)” (Figure 1). This work continues to be widely used by Chinese Christian communities in mainland China and beyond, even though it is hardly sung in the land of its origin. Other popular works in this category include John Newton’s “Amazing Grace,” Stuart Hine’s translation of “How Great Thou Art,” and contemporary worship songs like Rick Founds’ “Lord, I Lift Your Name On High” (1989) [17], Tim Hughes’ “Here I Am to Worship” (2001) [18], and Chris Tomlin’s “How Great Is Our God” (2004) [19].

Figure 1.

“The Lord Is in His Holy Temple” by George Root.

In the mid-20th century, Global South churches began to be self-determining in their polity and ministry. At the same time, Asian theologians such as Choan Seng Song of Taiwan, Kosuke Koyama of Japan, Ahn Byung Mu of South Korea, and Madathilparampil Mammen Thomas of India, among others, sought to express contextual theologies for their respective contexts. Yet as Simon Chan, in his 2014 book, Grassroots Asian Theology, critically observed, the substantive contents of their theologies are not reflected on the ground [20]. At best, what Asian theologians deemed as important indigenous Christian thoughts remained marginalized by mainstream Asian Christianity, as in the case of Dalit theology in India and Minjung theology in South Korea. In fact, most Asian-based theologies that have caught the imagination of the Church in the West continue to remain in the realm of academia. It is also similar in the arena of church music. While there is an emerging consciousness of the need for contextualization, such efforts tend to be tentative.

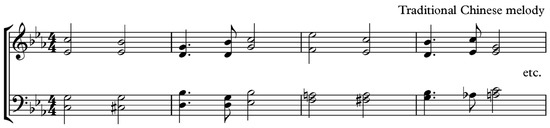

This next stage of contextualization is marked by musicking using local melodies. These tunes often are affixed with Western harmonization. The Adapted Song is an effort to embrace local expression, to break the inherited potted Gospel and plant it in local soil. However, with Western musical practices still being highly esteemed, musicking in this stage of contextualization is a juxtaposition, often treating a local melody that is typically monophonic with four-part homophonic arrangement or in other Western popular musical nuance (Figure 2). Typically speaking, the architects for this song type, however, are locals who are skillful in music creation. In China, well-regarded retired pastor and eminent Chinese church music personality Rev. Shi Qigui would be an example ([21,22]).

Figure 2.

An excerpt of hymn tune, 宣平 XUAN PING. [23]

Following the ascent of contemporary worship musicking in the West, Chinese Christianity has also embraced this phenomenon. 耶希亚圣乐 (J.H.A. sacred music service) which is based in Wenzhou, Zhejiang province of Eastern China, is one such local Christian musicking group [24] An example of their contemporary Christian music-making effort is 主我寻求你 (“Lord, I Seek You”) from their 2015 recording project, 回到你面前 (Returning to Your Presence) [25].

The Chinese Christian diaspora has also been active in musicking, and some of their efforts have become songs of the heart for mainland China Christian communities. Organizations such as California-based 讚美之泉 (Streams of Praise Music Ministries) [26], 小羊敬拜音乐事工 (Lamb Music | Warrior Bride Worship Ministry) [27], 我心旋律 (Melody of My Heart Music Ministry) [28], and Taipei-based 約書亞樂團 (Joshua Band) [29], among others, have created an impetus for local musicking in China. Their productions exhibit an awareness of local idioms and clearly represent the Adapted Song.

In contrast with the Adopted and Adapted Songs is the Actualized Song. This genre draws on the local culture for inspiration and idiomatic expressions at the expense of overt Western nuances. In the context of Christianity in China, an obvious example would be the 1500 songs of 迦南诗歌 (Canaan Hymns), composed by 吕小敏 (Ruth Lu Xiao-min) from Henan province [30,31,32]. An example of one of her compositions is 最知心的朋友 (“My Dearest Friend”) [33]. The sinicization potential of this genre is apparent from the reaction of a mainland Chinese Christian about this repertoire. She says,

From my heartfelt perspective, the Canaan hymns are God’s gift to the Chinese people. When I sing hymns translated from other languages, I feel that I am walking into the kingdom of God. Now it is like God is walking into our hearts, taking care of all our needs through the Canaan hymns. He encourages us when we are weak, he strengthens us when we lose hope, he gives us power when we need it. He guides us with these hymns. So I think the Canaan hymns are absolutely right for the Chinese Church. They touch me very deeply.[34]

The shift towards the Actualized Song is also apparent in the publication of the 2009 hymnal supplement, 讚美诗(新编)补充本 (Supplement of The New Hymnal) of China’s official church, 三自教会 (TSPM) Church. In comparison with its predecessor, 讚美诗 (The New Hymnal), the repertoire of this supplement is intently focused on showcasing local works. Within the 200 songs in this publication, there are 61 local compositions, of which 54 are new works.

3. Musicking and Sinicization

Both of these congregational songbooks are helpful indicators of the progress of contextualization of congregational song in China. Nevertheless, it is difficult to secure empirical data regarding the state of musicking within the churches in China. As Paul Bradshaw observed, “liturgical texts can go on being copied long after they ceased to be used” ([30], p. 5). The same is true in musicking. The official adoption of hymnals by a congregation does not indicate that the corpus is used in musicking. There may be instances where hymnals are found in pews, but the congregation uses an alternative repertoire. In light of the historical maltreatment of Christians in China, the lack of reporting of songs for copyright licensing purposes, and the proliferation of multimedia technology in the present time, the actual repertoire of any given congregation is not easily determined. Moreover, it is exceedingly difficult to document musicking given the contextual reality in China, where faith and its practice are overtly politicized. Bradshaw’s observation is illuminating here when he posits,

Nobody has the courage to say, “Let’s drop this from our formularies,” since to do so would appear to be somehow of a betrayal of our heritage, a reneging on our ancestors in the faith, or a wanton disregard for tradition. So it goes on appearing in the book, and everyone knows that when you reach it in the order of worship, you simply turn the page and pass over it to the next prayer or whatever.([35], p. 6)

Nevertheless, the desire for local expression and the frustration of implementation is evident in the opinion of church music composer Shi, who remarked,

Equally telling is the observation from Amity News Service, the publication agency for the official China Christian Council, indicating that “well-known foreign hymns such as ‘Holy, Holy, Holy!’ and ‘O God, Our Help in Ages Past’ are still central to the musical life of large numbers of Chinese Christians and that Chinese churches are still very Western in forms of worship, music and theology” ([22], p. 210). This clearly indicates that Adopted and Adapted Songs are dominant forms in the Chinese congregational song corpus compared to Actualized Song. This experience is similar to the musicking experiences of other Asian Christianities [36,37,38].It is very difficult. Quite a few Chinese believers and workers have become used to singing foreign hymns. If you don’t let them sing foreign hymns, they will feel they are not really singing hymns at all. I am a musical worker. I feel we Chinese should sing our own hymns made by ourselves. Luther thought they should have German hymns. But there are quite a few Chinese believers who do not like Chinese hymns. They still like old things.([22], p. 210)

4. Looking Ahead: What Does It Mean?

Therefore, if the intent is to develop sinicized Christianity via musicking, the way forward is for authorities to encourage and nurture the growth of the Actualized Song. Equally important is for them to appreciate musicking’s tendency to lean towards communal meaning-making, where “each performance articulates the values of a specific social group, large or small, powerful or powerless, rich or poor, at a specific point in history” ([11], p. 133). At the same time, authorities need to realize and accept that Christianity bears certain Western traits because these traits are its historical legacy. Christianity, like culture, is not static: it is shaped by a myriad of sociocultural forces, and as it grows its roots in the culture, its outlook and expression will change ([7], pp. 155–74). Through the contextualization process, Christianity will hold in tension its “dogma, inheritances, and lived experiences within a specific socio-cultural context” ([39], p. 131). As such, purposeful effort in sinicization needs to be based on dialectical mutuality with reciprocal understanding and respect as core values between the Church and the State. Unilateral assertion by either party over the other would negate the authenticity of musicking and distort the faith community. This is because musicking maintains an interdependent relationship with the community it constitutes. In this relationship, the community relies on musicking for its construction, while the relevance of musicking is authenticated by the community’s continued use.

Therefore, within the process of contextualization, these various song types would co-exist, albeit in different constitutions through different phases. In the initial phase of contextualization, it would be natural for local Christianities to have their mediascapes dominated by translated and adopted expressions. While there would be some awareness of local nuances, this is neither influential nor significant to the community. In time, Christianity would display growing cultural sensitivity and local setting awareness. The maturing phase would see nascent efforts of adaptation that draw on both Western and local resources. With greater self-awareness, Christianity would increasingly turn to local resources for musicking as such expressions gained traction with the community for meaning-making. There would then be less dependency on adopted expressions, though I contend that the Adopted Song would still be present because it remains valued as the Church’s legacy. Thus, the sign of sinicized Christianity is the presence and consistent use of Adapted and Actualized Songs.

In conclusion, through this essay I have attempted to offer an alternative approach to the sinicization of Christianity, in view of recent changes in the sociocultural landscape in mainland China. While mainland Chinese authorities have sought to sinicize the faith through redressing theological thought, I contend that this approach is inappropriate as it presumes Christianity to be an ideological construct. In challenging this assumption, I suggest that Christianity is a narrative of God’s acts that can be mediated through a mediascape, given the latter’s tendency for narrative-based and imagery-rich construction. To investigate this hypothesis, I propose music as an effective avenue. In using Small’s concept of musicking, which emphasizes relational encounter, I have shown that the three congregational song types of Adopted, Adapted, and Actualized are suitable markers denoting the phases of contextualization. I assert that sinicized Christianity would reflect overt use of Adapted and Actualized Songs just as the maturing phase of contextualization would. At the same time, I caution that efforts in sinicization need to be cognizant of the church’s primordial traits and the need for prudence given the organic nature of the process of contextualization. In closing, I turn to Saint Augustine, who in his commentary on Psalm 73:1, on the purpose of musicking, notes,

For he that sings praise, not only praises, but only praises with gladness: he that sings praise, not only sings, but also loves Him of whom he sings. In praise, there is the speaking forth of one confessing; in singing, the affection of one loving.([40]3, p. 577)

Ultimately, sinicized Christianity needs to have as its core purpose the nurturing of heartfelt worship, in which Chinese culture serves as a resource. It would be folly to politicize pietistic expressions for ideological purposes, as that would negate the efficacy of these expressions of meaning-making in the community. Where form exists without the power to transform, society is inevitably impoverished.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References and Notes

- Eleanor Albert. “Christianity in China.” CFR Backgrounder. 7 May 2015. Available online: http://www.cfr.org/china/christianity-china/p36503 (accessed on 28 March 2017).

- Hongyi Wang. “China Plans Establishment of Christian Theology.” China Daily. 7 August 2014. Available online: http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2014-08/07/content_18262848.htm (accessed on 28 March 2017).

- Arjun Appadurai. “Disjuncture and Difference in the Global Cultural Economy.” Theory, Culture, and Society 7 (1990): 295–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercy A. Kuo. “The Politics of Religion in China: Insights from Fenggang Yang.” The Diplomat. 4 August 2016. Available online: http://thediplomat.com/2016/08/the-politics-of-religion-in-china/ (accessed on 28 March 2017).

- I-to Loh. “Toward Contextualization of Church Music in Asia.” In The Hymnology Annual. Edited by Vernon Wicker. Berrien Springs: Vere Publishing Ltd., 1991, vol. 1, pp. 89–114. [Google Scholar]

- I-to Loh. “Toward Contextualization of Church Music in Asia.” Asian Journal of Theology 4 (1990): 293–315. [Google Scholar]

- Swee Hong Lim. Giving Voice to Asian Christians: An Appraisal of the Pioneering Work of I-To Loh in the Area of Congregational Song. Saarbrücken: VDM Verlag, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Albert van den Heuvel. “Preface.” In Risk: New Hymns for a New Day. Geneva: World Council of Churches, 1966, pp. 6–9. [Google Scholar]

- Kofi Agawu. Music as Discourse: Semiotic Adventures in Romantic Music. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009, p. 20. [Google Scholar]

- Jean Molino. “Musical Fact and the Semiology of Music.” Music Analysis 9 (1990): 113–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher Small. Musicking: The Meanings of Performing and Listening. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Martin Luther. “Preface to Symphoniae iuncundae 1538.” In Luthers Wereke: Kritische Gesamtausgabe. Weimar: Bohlau, 1914, vol. 50. [Google Scholar]

- Robin A. Leaver. Luther’s Liturgical Music: Principles and Implications. Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Steven Kimbrough Jr. The Lyrical Theology of Charles Wesley: A Reader. Eugene: Cascade Books, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel Thambyrajah Niles. “Saranam, Saranam.” United Methodist Hymnal, 1963, 523. [Google Scholar] quoted in C. Michael Hawn. History of Hymns. 14 August 2014. Available online: http://www.umcdiscipleship.org/resources/history-of-hymns-saranam-saranam (accessed on 28 March 2017).

- Daniel Thambyrajah Niles. “Christianity in a Non-Christian Environment.” The Student World 47 (1954): 259–64. [Google Scholar]

- Rick Founds. “Lord, I Lift Your Name on High (主我高举你的名).” Available online: https://youtu.be/KcOVTGTcX3c (accessed on 28 March 2017).

- Tim Hughes. “Here I Am to Worship (我在這裡敬拜).” Available online: https://youtu.be/8wo_DqKGmwM (accessed on 28 March 2017).

- Chris Tomlin. “How Great Is Our God (我神真偉大).” Available online: https://youtu.be/AP3zwcaV8GE (accessed on 28 March 2017).

- Simon Chan. Grassroots Asian Theology: Thinking the Faith from the Ground Up. Downers Grove: Inter Varsity Press, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Britt Towery, and David M. Paton. Christianity in Today’s China: Taking Root Downward, Bearing Fruit Upward. Bloomington: Authorhouse, 2000, pp. 61–62, For a brief biographical account of Rev. Shi Qigui. [Google Scholar]

- John Craig William Keating. A Protestant Church in Communist China: Moore Memorial Church Shanghai 1949–1989. Bethlehem: Lehigh University Press, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 宣平 (XUAN PING) is a Traditional Chinese tune matched to the text: Tzu-chen Chou. “收成谢恩歌 (Praise Our God Above for His Boundless Love).” In 成谢恩歌 (The New Hymnal). Edited by The New Hymnal Editorial Committee. Shanghai: National TSPM & CCC, 1999, number 184. [Google Scholar]

- “耶希亚圣乐 (JHS Sacred Music Service).” Available online: http://www.zanmeishi.com/artist/jha/detail.html (accessed on 28 March 2017).

- 耶希亚圣乐 (JHS Sacred Music Service). “主我寻求你 (Lord, I Seek You).” 2014. Available online: https://www.fuyin.tv/html/2583/38741.html (accessed on 28 March 2017).

- Streams of Praise Music Ministries. “除你以外 (诗篇七十三篇) (Whom have I in Heaven but You (Psalms 73)).” 2009. Available online: https://youtu.be/7YXEQU2nhOE (accessed on 28 March 2017).

- Lamb Music. “來吧, 我們讚美 (Come Let Us Praise Him).” 2014. Available online: http://www.lambmusic.org/songs/m_letspraise.php (accessed on 28 March 2017).

- Melody of My Heart Music Ministry. “單單敬拜 (Simply Worship).” 2011. Available online: http://www.momh.org/album/album8.php (accessed on 28 March 2017).

- Joshua Band. “一生跟隨你 (I Will Follow You, Lord).” 2011. Available online: https://youtu.be/hIzUVGU9qyM (accessed on 28 March 2017).

- Michelle Garver. “Xiao Min.” Women of Christianity. 2013. Available online: http://womenofchristianity.com/hymn-writers/xaio-min/ (accessed on 28 March 2017). For a brief biographical account of Xiao Min

- David Aikman. Jesus in Beijing: How Christians is Transforming China and Changing the Global Balance of Power. Washington: Regnery Publishing, 2006, pp. 108–14, For a brief biographical account of Xiao Min. [Google Scholar]

- Irene Ai-Ling Sun. “Songs of Canaan: Hymnody of the House-Church Christians in China.” Studia Liturgica 37 (2007): 98–116, Read for additional information about Canaan hymns. [Google Scholar]

- Xiaomin Lu. (吕小敏). “My Dearest Friend (最知心的朋友).” 2009. Available online: https://youtu.be/fvUsgi3gxJU (accessed on 28 March 2017).

- China Soul for Christ Foundation. “The Canaan Hymns. (English version).” Video, 7:00–7:33, posted by James Hee. 21 October 2012. Available online: https://youtu.be/xa1saiWejjo (accessed on 28 March 2017).

- Paul F. Bradshaw. The Search for the Origins of Christian Worship: Sources and Methods for the Study of Early Liturgy. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Seongdae Kim. “Korean hymnody.” In The Canterbury Dictionary of Hymnology. Norwich: Canterbury Press, 2013, Available online: http://www.hymnology.co.uk/k/korean-hymnody (accessed on 28 March 2017).

- Yasuhiko Yokosaka. “Japanese hymnody.” In The Canterbury Dictionary of Hymnology. Norwich: Canterbury Press, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- I-to Loh. “Taiwanese hymnody.” In The Canterbury Dictionary of Hymnology. Norwich: Canterbury Press, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Swee Hong Lim. “Church Music in Postcolonial Liturgical Celebration.” In Postcolonial Practice of Ministry: Leadership, Liturgy, and Interfaith Engagement. Edited by Kwok Pui-lan and Stephen Burns. Lanham: Lexington Books, 2016, pp. 123–36. [Google Scholar]

- Saint Aurelius Augustine. “Commentary on Psalm 73:1.” In Expositions on the Psalms, digital ed. Wenham: Public Domain, 2007, Available online: https://faculty.gordon.edu/hu/bi/ted_hildebrandt/otesources/19-psalms/text/books/augustine-psalms/augustine-psalms.pdf (accessed on 28 March 2017).

- 1This is one of five theoretical dimensions that Arjun Appadurai (1949–) developed in addressing global cultural flows. The remaining four being ethnoscapes, technoscape, finanscape, and mediascapes.

- 2The phrase “we are what we sing” is my adaptation of Albert van den Heuvel’s remark when he wrote, “Tell me what you sing, and I’ll tell you who you are!”

- 3Latin text: Qui enim cantat laudem, non solum laudat, sed etiam hilariter laudat; qui cantat laudem, non solum cantat, sed et amat eum quem cantat. In laude confitentis est praedicatio, in cantico amantis affectio…

© 2017 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).