From Contextual Theology to African Christianity: The Consideration of Adiaphora from a South African Perspective

Abstract

:The strain of having to live by double standards for African converts brought about some difficulties in the appreciation of the Christian identity. The principal concern was: “What should be the proper relationship between Christian identity and a Christian’s cultural identity?” (Mugambi 2002, p. 520). As expected, there were no simple answers to this enquiry. But suggestions towards the consideration of inculturation (Magesa 2004; Mbiti 1975; Bujo 2003)1; the reformation or reconstruction of Christianity in Africa (Mugambi 1995; Shorter 1975); and the Africanisation of Christianity, seemed to be more favourable (Oden 2007; Van der Merwe 2016; Akao 2002).On the one hand, they accepted the norms introduced by the missionaries who saw nothing valuable in African culture. On the other hand, the converts could not deny their own cultural identity. They could not substitute their denominational belonging for their cultural and religious heritage. Yet they could not become Europeans or Americans merely by adopting some aspects of the missionaries’ outward norms of conduct.

This analogy, therefore, seems to qualify the scholastic language of speaking of Christianity as having arrived in Africa as part of the Western campaign of civilization, which was meant to redeem the ‘Dark Continent’ from the claws of ignorance and devilish superstitions (Bediako 1992, p. 225; Bosch 1991, pp. 227, 312–13). In this narrative, Christianity was equated to western culture, hence the need for African Christianity arose.Christianity began within the Jewish culture. That culture became incapable of sustaining the Christian faith because the leaders of Judaism believed that the new faith was a threat to the Jewish culture […]. Then it was greatly influenced by Greek philosophy, without being swallowed by it. In the fourth century Christianity became the popular religion of the Roman Empire, after the conversion of Emperor Constantine […]. During the modern missionary enterprise Christianity was riding on western culture.

Thus, the common racial origin of Africans and the similarities in their culture and beliefs, deems it appropriate to conceive of the ATR in the singular rather than in plural.Although they (African religious systems) were separate and self contained systems, they interact with one another and influenced one another to different degrees. This justifies our using the term African Traditional Religion in the singular to refer to the whole African religious phenomena, even if we are, in fact, dealing with multiplicity of theologies.

[W]hen Africans migrate in large numbers from one part of the continent to another, or from Africa to other continents, they take religion with them. They can only know how to live within their religious context. Even if they are converted to another religion like Christianity or Islam, they do not completely abandon their traditional religion immediately: it remains with them for several generations and sometimes centuries.

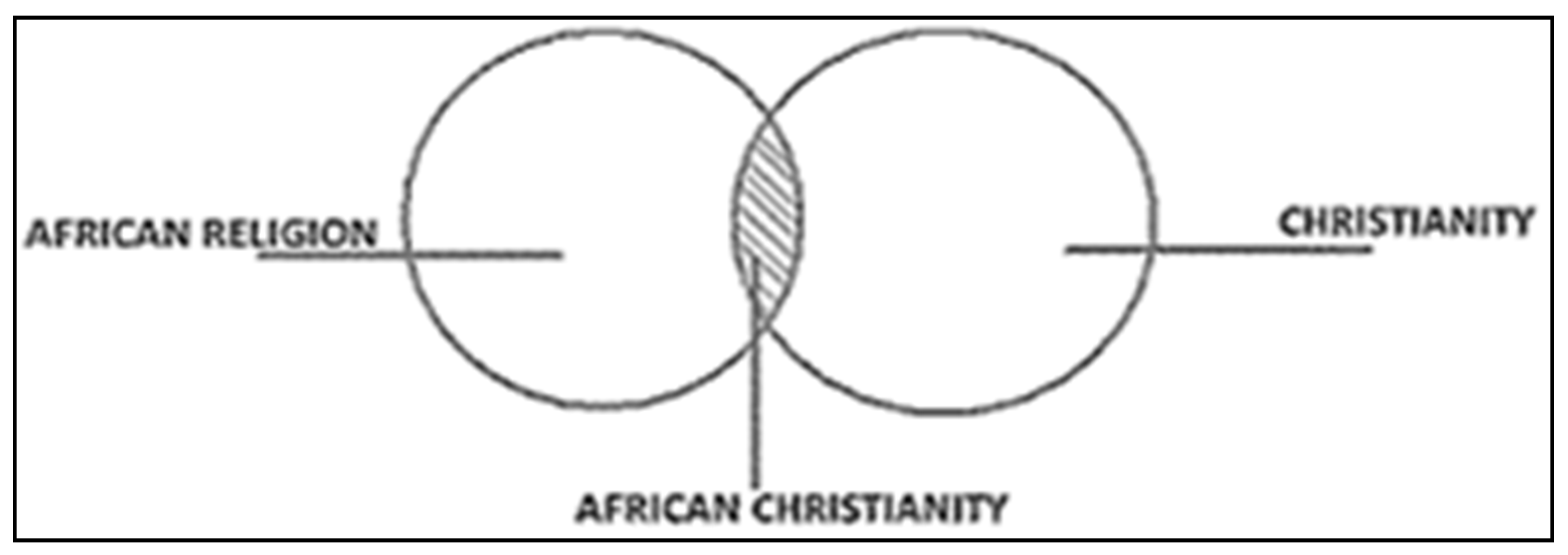

Thus, the African rigorist perspective argues that one cannot be an African religionist while a Christian at the same time. This perspective however, seems to overlook the reality of people who amalgamate the two systems—Christianity and ATR, and hold that they are related systems of thought and practice. It is a known fact that there are Africans who regard themselves as Christians while they are also traditional healers, or continue to practice their traditional customs (Mlisa 2009, p. 8; Hirst 2005, p. 4). This African rigorist view seems to undermine the existence of such a reality. This view further seems to suggest that converting to Christianity, as Mbiti (1975, p. 13) and Leonard (1906, p. 429) argued, is almost impossible because Africans find it difficult to renounce their traditional cultures and religious beliefs.One wonders how one can officiate in a ritual professing ancestors as intermediaries between humanity and God, and at the same time go to church and preach that Jesus is the way, the truth and the life? Surely these two practices are based on mutually exclusive, irreconcilable tenets of faith; a contradiction in terms.

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adamo, David T. 2011. Christianity and the African Traditional Religion(s): The Postcolonial Round of Engagement. Verbum et Ecclesia 32: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akao, John O. 2002. The Task of African Theology: Problems and Suggestions. Scriptura 81: 341–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amanze, James N. 2003. Christianity and Ancestor Veneration in Botswana. Studies in World Christianity 8: 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, Allan. 2000. Zion and Pentecost: The Spirituality and Experience of Pentecostal and Zionist/Apostolic Churches in South Africa. Pretoria: Unisa Press. [Google Scholar]

- Awolalu, Omosade J., and Adelumo P. Dopomu. 1979. West African Traditional Religion. Ibadan: Onibonoje Press & Book Industries. [Google Scholar]

- Awolalu, Omosade J. 1976. Sin and its Removal in African Traditional Religion. Journal of the American Academy of Religion 44: 275–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, Gregory A. 2005. Christianity: A Guide to Christianity. Oxford: The Subject Centre for Philosophical and Religious Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Bediako, Kwame. 1992. Theology and Identity: The Impact of Culture upon Christian Thought in the Second Century and Modern Africa. Oxford: Regnum Books International. [Google Scholar]

- Bediako, Kwame. 1994. Understanding African Theology in the 20th Century. Themelios 20: 14–20. [Google Scholar]

- Bosch, David J. 1991. Transforming Mission: Paradigm Shifts in Mission Theology. Maryknoll: Orbis Books. [Google Scholar]

- Bujo, Bénézet. 2003. Foundations of an African Ethic: Beyond the Universal Claims of Western Morality. Nairobi: Paulines Publications Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Buthelezi, Manas. 1986. Toward Indigenous Theology in South Africa. In Third World Liberation Theologies: A Reader. Edited by Dean W. Ferm. Maryknoll: Orbis Books, pp. 205–21. [Google Scholar]

- Carson, Donald A. 2015. On Disputable Matters. Themelios 40: 383–88. [Google Scholar]

- Crafford, Dionne. 2015. African Traditional Religions. In South Africa, Land of Many Religions. Edited by Arno Meiring and Piet Meiring. Wellington: Christian Literature Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, Richard G. 2009. Sancta Indifferentia and Adiaphora: “Holy Indifference” and “Things Indifferent”. Common Knowledge 15: 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasholé-Luke, Edward W. 1975. The Quest for an African Christian Theology. The Ecumenical Review 27: 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiedler, Klaus. 1996. Christianity and African Culture: Conservative German Protestant Missionaries in Tanzania, 1900–1940. Leiden and Boston: E. J. Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Futhwa, Fezekile. 2011. Sesotho Afrikan Thought and Belief Systems. Alberton: Nalane Publication. [Google Scholar]

- Hammond-Tooke, David W. 1974. The Bantu-Speaking Peoples of Southern Africa. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Publication. [Google Scholar]

- Hastings, Adrian. 1989. African Catholicism—An Essay in Discovery. London: SCM Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hirst, Manton M. 2005. Dreams and Medicines: The Perspective of Xhosa Diviners and Novices in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. Indo-Pacific Journal of Phenomenology 5: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirst, Manton M. 2007. A River of Metaphors: Interpreting the Xhosa diviner’s myth. Journal of African Studies 56: 217–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, Monica. 1936. Reaction to Conquest: Effects of Contact with Europeans on the Pondo of South Africa. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Idowu, Bolaji E. 1973. African Traditional Religion: A Definition. London: SCM Press. [Google Scholar]

- Isichei, Elizabeth. 1995. A History of Christianity in Africa: From Antiquity to the Present. Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis, Michael. 2009. Ubuntu Christianity. Wellington: Fact and Faith Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Jebadu, Alexander. 2007. Ancestral Veneration and the Possibility of its Incorporation into the Christian Faith. Exchange 36: 246–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabasele, Francois L. 1991. Christ as Ancestor and Elder Brother. In Faces of Jesus in Africa. Edited by Robert J. Schreiter. New York City: Orbis Books, pp. 116–27. [Google Scholar]

- Lado, Ludovic. 2006. The Roman Catholic Church and African Religions: A problematic encounter. The Way 45: 7–21. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard, Arthur G. 1906. The Lower Niger and It’s Tribes. London: Macmillan and Company, Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Magesa, Laurenti. 1998. African Religion: The Moral Traditions of Abundant Life. Nairobi: Paulines Publications Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Magesa, Laurenti. 2004. Anatomy of Inculturation: Transforming the Church in Africa. Maryknoll: Orbis Books. [Google Scholar]

- Maimela, Simon S. 1985. Salvation in African Traditional Religion. Missionalia 13: 63–77. [Google Scholar]

- Maluleke, Tinyiko S. 2005. Half a Century of African Christian Theologies: Elements of the Emerging Agenda for the Twenty-First Century. In African Christianity: An African Story. Edited by Ogbu. U. Kalu. Pretoria: University of Pretoria, pp. 469–93. [Google Scholar]

- Maluleke, Tinyiko S. 2010. Africanised Bees and Africanised Churches: Ten Theses on African Christianity. Missionalia: Southern African Journal of Mission Studies 38: 369–79. [Google Scholar]

- Mathema, Zacchaeus A. 2007. The African Worldview: A Serious Challenge to Christian discipleship. Ministry, International Journal for Pastors 79: 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Matobo, Thope A., M. Makatsa, and Emeka E. Obioha. 2009. Continuity in the Traditional Initiation Practice of Boys and Girls in Contemporary Southern African Society. Studies of Tribes and Tribals 7: 105–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, Philip, and Iona Mayer. 1974. Townsmen or Tribesmen: Conservation and the Process of Urbanization in a South African City. Cape Town: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mbiti, John S. 1969. African Religions and Philosophy. London: Heinemann Educational Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Mbiti, John S. 1975. Introduction to African Religion. London: Heinemann Educational Books. [Google Scholar]

- Mbiti, John S. 1977. The Biblical Basis for Present Trends in African Theology. In African Theology en Route: Papers from the Pan-African Conference of Third World Theologians, Accra, December 17–23 1977. Edited by Kofi Appiah-Kubi and Sergio Torres. Maryknoll: Orbis Books, pp. 83–94. [Google Scholar]

- Mbiti, John S. 1990. African Religions and Philosophy. Oxford: Heinemann International. [Google Scholar]

- Mbiti, John S. 1992. African Religions and Philosophy, 2nd ed. revised. London: Heinemann Educational Books. [Google Scholar]

- McGuire, Meredith B. 2008. Lived Religion: Faith and Practice in Everyday Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, Wallace G. 1995. Missionaries, Xhosa Clergy and the Suppression of Traditional Customs. In Missions and Christianity in South African History. Edited by Henry C. Bredenkamp and Robert J. Ross. Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press, pp. 153–72. [Google Scholar]

- Mlisa, Nomfundo L. 2009. Ukuthwasa, the Training of Xhosa Women as Traditional Healers. Ph.D. Thesis, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Mndende, Nokuzola. 2009. Tears of Distress: Voices of a Denied Spirituality in a Democratic South Africa. Dutywa: Icamagu Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Mndende, Nokuzola. 2013. Law and Religion in South Africa: An African Traditional Perspective. Nederduitse Gereformeerde Teologiese Tydskrif 54: 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogoba, Mmutlanyane S. 2011. The Religious Background to African Christianity: African Traditional Religion. In The Journey of Hope: Essays in Honour of Dr Mmutlanyane Stanley Mogoba. Edited by Itumeleng Mekoa. Cape Town: The Incwadi Press, pp. 170–85. [Google Scholar]

- Mokhoathi, Joel. 2017. Imperialism and its effects on the African Traditional Religion: Towards the liberty of African Spirituality. Pharos Journal of Theology 98: 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Motlhabi, Mokgethi G. 1994. Black or African Theology? Towards an Integral African Theology. Journal of Black Theology in South Africa 8: 113–41. [Google Scholar]

- Mtuze, Peter T. 2003. The Essene of Xhosa Spirituality: And the Nuisance of Cultural Imperialism: Hidden Presences in the Spirituality of the annaXhosa of the Eastern Cape and the Impact of Christianity on Them. Florida Hills: Vivlia Publishers and Booksellers. [Google Scholar]

- Mugambi, Jesse N. K. 1995. From Liberation to Reconstruction: African Christian Theology after the Cold War. Nairobi: East African Educational Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Mugambi, Jesse N. K. 2002. Christianity and the African Cultural Heritage. In Christianity and African Culture. Edited by Jesse. N. K. Mugambi. Nairobi: Acton Publications, pp. 516–42. [Google Scholar]

- Muzorewa, Gwinyai. H. 1985. The Origins and Development of African Theology. Maryknoll: Orbis Books. [Google Scholar]

- Ntombana, Luvuyo. 2015. The Trajectories of Christianity and African Ritual Practices: The Public Silence and the Dilemma of Mainline or Mission Churches. Acta Theologica 35: 104–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwibo, Joseph. 2010. A Brief Note on the Need for African Christian Theology. Paper presented at the Cursus Godsdient Onderwijs (CGO-HBO), Lienden, The Netherlands, September 22. [Google Scholar]

- Nxumalo, Jabulani A. 1981. Zulu Christians and Ancestor Cult: A Pastoral Consideration. In Ancestor Religion in Southern Africa. Edited by Heinz Kuckertz. Transkei: Lumko Missiological Institute, pp. 65–78. [Google Scholar]

- Nyamiti, Charles. 1984. Christ as Our Ancestor: Christology from an African Perspective. Gweru: Mambo Press. [Google Scholar]

- Oden, Thomas C. 2007. How Africa Shaped the Christian Mind: Rediscovering the African Seedbed of Western Christianity. Westmont: InterVarsity Press Books. [Google Scholar]

- Oduro, Thomas, Hennie Pretorius, Stan Nussbaum, and Bryan Born. 2008. Mission in an African Way: A Practical Introduction to African Instituted Churches and Their Sense of Mission. Wellington: Christian Literature Fund and Bible Media Publication. [Google Scholar]

- Onuzulike, Uchenna. 2008. African Crossroads: Conflicts between African Traditional Religion and Christianity. The International Journal of the Humanities 6: 163–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pityana, Nyameko B. 1999. The Renewal of African Moral Values. In African Renaissance: The New Struggle. Edited by William M. Makgoba. Sandton: Mafube Publishing, pp. 137–48. [Google Scholar]

- Richter, Marlise. 2003. Traditional Medicines and Traditional Healers in South Africa. Discussion Paper Prepared for the Treatment Action Campaign and AIDS Law Project. Available online: http://www.tac.org.za/Documents/ResearchPapers/Traditional_Medicine_briefing.pdf (accessed on 29 November 2017).

- Sanou, Boubakar. 2013. Missiological Perspectives on the Communal Significance of Rites of Passages in African Traditional Religions. Journal of Adventist Mission Studies 9: 39–52. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, Rosalind, and Charles Stewart. 1994. Introduction: Problematizing syncretism. In Syncretism/Anti-Syncretism: The Politics of Religious Synthesis. Edited by Charles Stewart and Rosalind Shaw. London: Routledge Press, pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Shorter, Aylward. 1975. African Christian Theology: Adaptation or incarnation? Michigan: Geoffrey Chapman. [Google Scholar]

- Southern African Catholic Bishops. 2006. Ancestor Religion and the Christian Faith. Paper presented at Resolution 2.5.2 of the Plenary Session of the Southern African Catholic Bishops’ Conference, Mariannhill, KwaZulu Natal, South Africa, August 11. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, Charles. 1994. Syncretism as a Dimension of National Discourse in Modern Greece. In Syncretism/Anti-Syncretism: The Politics of Religious Synthesis. Edited by Charles Stewart and Rosalind Shaw. London: Routledge Press, pp. 127–44. [Google Scholar]

- The New Encyclopaedia Britannica. 2007. Mainstream Christianity: Definition. Chicago: Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Truter, IIse. 2007. African Traditional Healers: Cultural and Religious Beliefs Intertwined in a Holistic Way. SA Pharmaceutical Journal 74: 56–60. [Google Scholar]

- Tutu, Desmond. 1986. Black Theology and African Theology: Soulmates or Antagonists? In Third World Liberation Theologies: A Reader. Edited by Dean W. Ferm. Maryknoll: Orbis Books, pp. 256–64. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Merwe, Dirk. 2016. From Christianising Africa to Africanising Christianity: Some hermeneutical principles. Stellenbosch Theological Journal 2: 559–87. [Google Scholar]

- Wanamaker, Charles A. 1997. Jesus the Ancestor: Reading the Story of Jesus from an African Christian Perspective. Scriptura 62: 281–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, Monica. 1982. The Nguni People. In A History of South Africa to 1870. Edited by Monica Wilson and Leonard Thompson. Cape Town: David Philip Publication, pp. 75–130. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Tinyiko Maluleke (Maluleke 2005, p. 477) alludes to the urgency at which Africans sought to make Christianity communicate with their African cultural context. He notes that “from various fronts, African Christians insisted that the church of Africa and its theology must bear an African stamp”. In his view, this insistence moved beyond theological and ecclesiastical matters as other African thinkers also attempted to construct “African philosophy”, “African literature”, “African art”, and “African architecture”. |

| 2 | It is worth noting that some African scholars draw distinctions between “African theology” and “Black theology”, while others see the two concepts as interconnected. Manas Buthelezi (Buthelezi 1986, p. 220), for instance, seems to favour the notion of “Black theology” more than that of “African theology”; while Desmond Tutu (Tutu 1986, p. 262) regards both “African theology” and “Black theology” as soulmates (cf. Mokgethi Motlhabi 1994, pp. 113–41). |

| 3 | Traditional healers do not perform the same functions, nor do they fall into the same category but each traditional healer has a field of expertise, with their own methods of diagnosis and a particular set of knowledge in traditional medicines (cf. Ilse Truter 2007, pp. 57–58). |

| 4 | A Sangoma or diviner is the most senior of the traditional healers. She or he is a person who defines an illness (diagnostician) and also divines the circumstances of the illness in the cultural context. Diviners are known by different names. For example, they are known as Igqirha in Xhosa, Ngaka in Northern Sotho, Selaoli in Southern Sotho, and Mungome in Venda and Tsonga. But most South Africans generally refer to them as Sangomas—from the Zulu word Izangoma (cf. IIse Truter 2007, p. 57). |

| 5 | For further discussions on this matter (cf. Donald A. Carson 2015, pp. 385–56). |

| 6 | African Independent or Initiated Churches (AICs), for instance, have taken a firm and decisive position on the inclusion of African traditional rituals into their Christian system. In most AICs, there is no apparent contradictions in the practice of African traditional rituals, which include the veneration of ancestors, with one being a committed Christian (cf. Ntombana 2015, pp. 106–7). |

| 7 | Wallace Mills (Mills 1995, pp. 153–72), however, notes that missionaries rejected the practice of traditional rites and customs. Among the Xhosas, for instance, traditional rites and customs such as circumcision (initiation rites), lobola (dowry, or bride-price), the drinking of traditional beer, etc. were opposed by missionaries. |

| 8 | James 1 vs. 2–3 reads as follows: “Consider it pure joy, my brothers, whenever you face trials of many kinds, because you know that the testing of your faith develops perseverance” (NIV translation). |

| 9 | According to Richter (2003), the WHO Centre for Health Development defines African traditional medicines as “the sum total of all knowledge and practices, whether explicable or not, used in diagnosis, prevention and elimination of physical, mental, or societal imbalance, and relying exclusively on practical experience and observation handed down from generation to generation, whether verbally or in writing”. |

| 10 | Mainstream Christianity, in this paper, refers to those Christian churches that follow the Nicene Creed and include the Roman Catholic Church, Eastern Orthodox, Anglican and major Protestant churches (cf. The New Encyclopaedia Britannica 2007). |

| 11 | Simon Maimela (Maimela 1985, p. 71) seems to have addressed this issue when he noted that for many Africans “the church is not interested in their daily misfortunes, illness, encounter with evil and witchcraft, bad luck, poverty, barrenness—in short, all their concrete social problems […]. Most Africans often do not know what to do with their new, attractive Christian religion and yet one which dismally fails to meet their emotional and spiritual needs”. He also framed this as the strength of AICs—they give Africans “an open invitation to bring concrete social problems to the church leadership”. |

| 12 | For further discussions on this matter (cf. Anderson 2000, pp. 30–31). |

| 13 | Nokuzola Mndende (Mndende 2013, p. 78) exemplifies this intersection when she states that “rituals are special gatherings of the clans aimed at communal religious practices”. This means that some agnatic group rituals carry a religious significance, even though they are taken as communal. |

| 14 | For further discussions (cf. Mayer and Mayer 1974, p. 151; Wilson 1982, p. 27). |

| 15 | Jabulani Nxumalo (Nxumalo 1981, p. 67) asserts the following: “In my view, there is a relationship between Christ and the ancestors, for the simple reason that Christ died too. He is therefore an idlozi (the living-dead) to us, since those who are dead are amadlozi (plural of idlozi) for us. Therefore Christ and those who have died are united together. We call them together in Christ”. |

© 2017 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mokhoathi, J. From Contextual Theology to African Christianity: The Consideration of Adiaphora from a South African Perspective. Religions 2017, 8, 266. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel8120266

Mokhoathi J. From Contextual Theology to African Christianity: The Consideration of Adiaphora from a South African Perspective. Religions. 2017; 8(12):266. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel8120266

Chicago/Turabian StyleMokhoathi, Joel. 2017. "From Contextual Theology to African Christianity: The Consideration of Adiaphora from a South African Perspective" Religions 8, no. 12: 266. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel8120266

APA StyleMokhoathi, J. (2017). From Contextual Theology to African Christianity: The Consideration of Adiaphora from a South African Perspective. Religions, 8(12), 266. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel8120266