Spirituality in Nursing: An Overview of Research Methods

Abstract

:1. Introduction

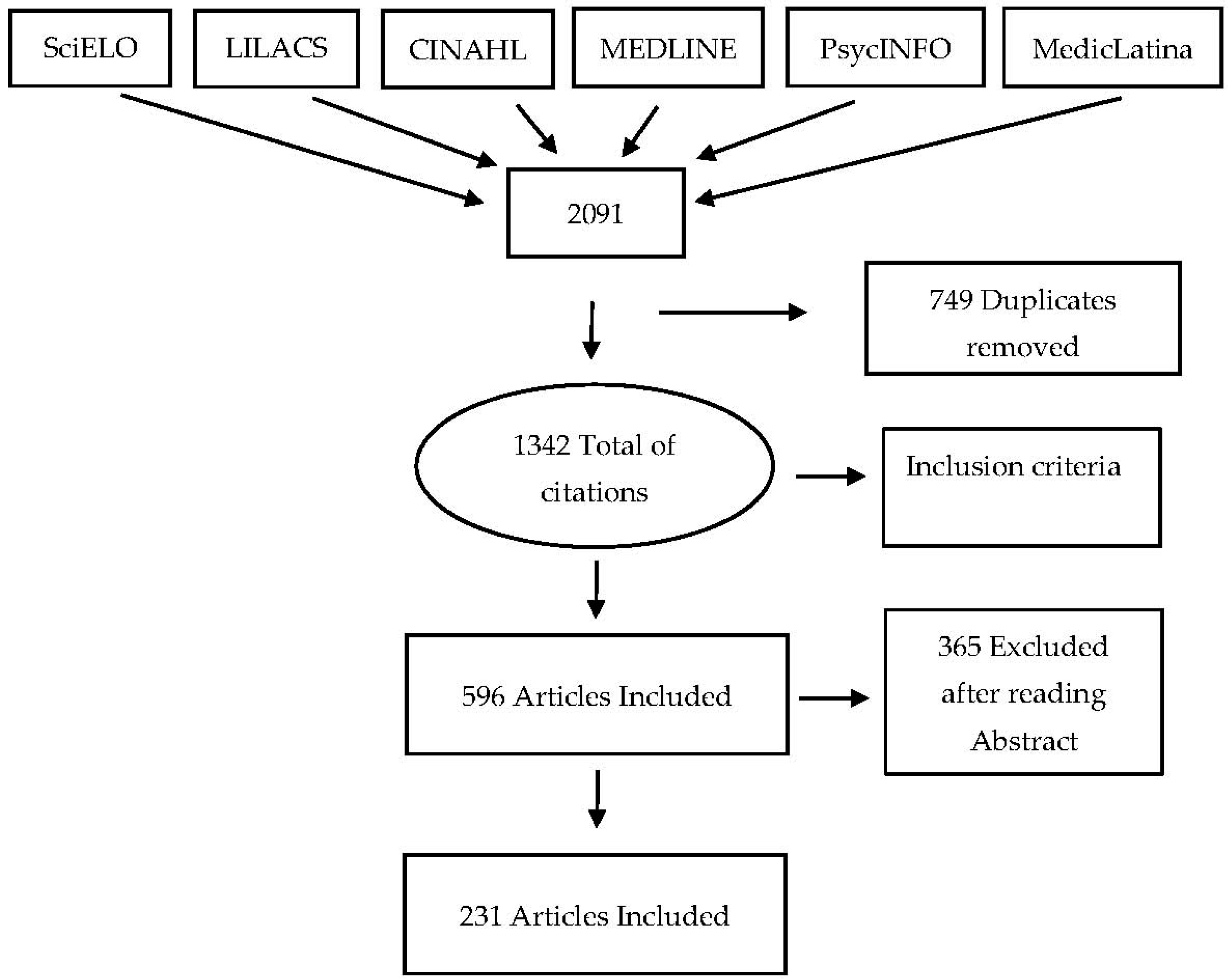

2. Materials and Methods

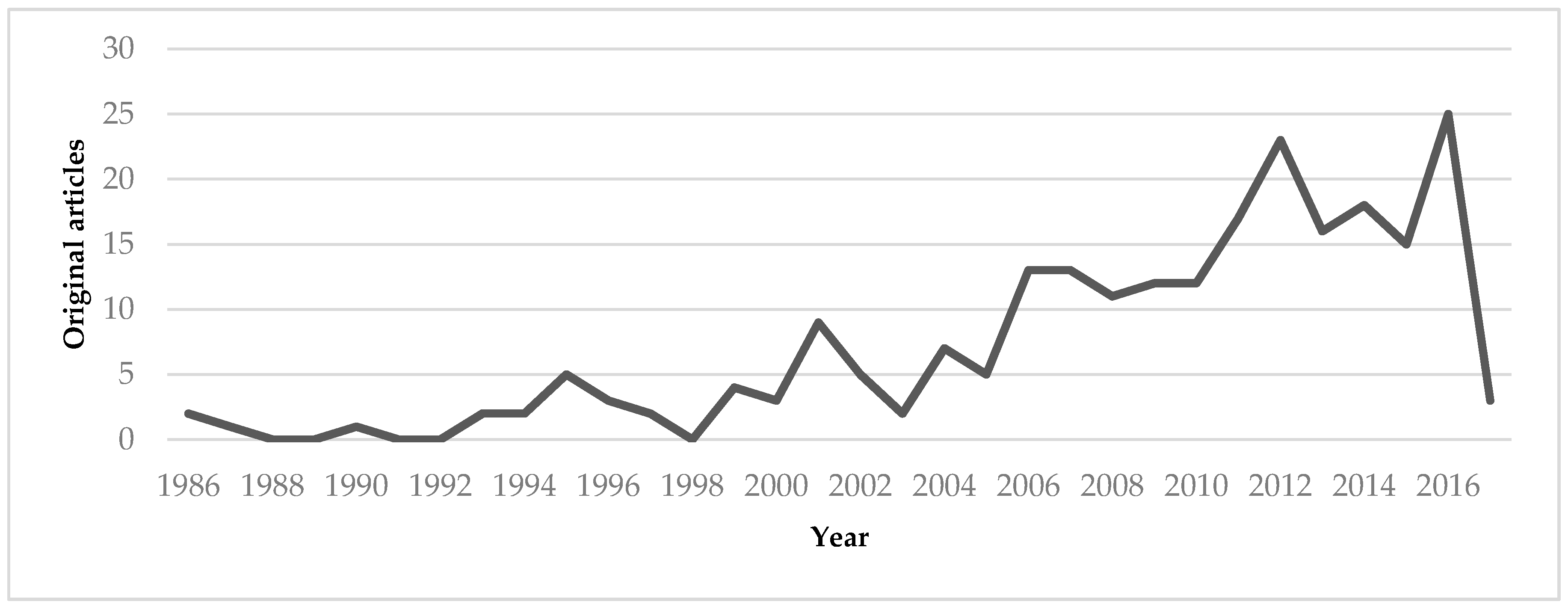

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aalen, Odd O., and Nina Gunnes. 2010. A Dynamic Approach for Reconstructing Missing Longitudinal Data Using the Linear Increments Model. Biostatistics (Oxford, England) 11: 453–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balboni, Tracy, Michael Balboni, Elizabeth M. Paulk, Andrea Phelps, Alexi Wright, John Peteet, Susan Block, Chris Lathan, Tyler VanderWeele, and Holly Prigerson. 2011. Support of Cancer Patients’ Spiritual Needs and Associations with Medical Care Costs at the End of Life. Cancer 117: 5383–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldacchino, Donia R. 2006. Nursing Competencies for Spiritual Care. Journal of Clinical Nursing 15: 885–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldacchino, Donia. 2015. Spiritual Care Education of Health Care Professionals. Religions 6: 594–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldeira, Sílvia Maria Alves, Erika da Cássia Lopes Chaves, Emília Campos de Carvalho, and Margarida Maria da Silva Vieira. 2012. Nursing Diagnoses Validation—The Differential Diagnostic Validation Model as a Strategy. Journal of Nursing UFPE 6: 1441–45. [Google Scholar]

- Caldeira, Sílvia, Emília Campos Carvalho, and Margarida Vieira. 2013. Spiritual Distress-Proposing a New Definition and Defining Characteristics. International Journal of Nursing Knowledge 24: 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caldeira, Sílvia, Amélia Simões Figueiredo, Ana Paula da Conceição, Célia Ermel, João Mendes, Erika Chaves, Emília Campos de Carvalho, and Margarida Vieira. 2016. Spirituality in the Undergraduate Curricula of Nursing Schools in Portugal and São Paulo-Brazil. Religions 7: 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldeira, Sílvia, Fiona Timmins, Emília Campos de Carvalho, and Margarida Vieira. 2017. Clinical Validation of the Nursing Diagnosis Spiritual Distress in Cancer Patients Undergoing Chemotherapy. International Journal of Nursing Knowledge 28: 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaves, Erika de Cássia Lopes, Emília Campos de Carvalho, Fábio de Souza Terra, and Luiz de Souza. 2010. Clinical Validation of Impaired Spirituality in Patients With Chronic Renal Disease. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem 18: 309–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, Janice. 2009. A Critical View of How Nursing Has Defined Spirituality. Journal of Clinical Nursing 18: 1666–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cleary, Michelle. 2016. Essentials of Building a Career in Nursing Research. Nurse Researcher 23: 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cockell, Nell, and Wilfred McSherry. 2012. Spiritual Care in Nursing: an Overview of Published International Research. Journal of Nursing Management 20: 958–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doyle, Louise, Anne-Marie Brady, and Gobnait Byrne. 2016. An Overview of Mixed Methods Research—Revisited. Journal of Research in Nursing 21: 623–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangelista, Carla Braz, Maria Emilia Limeira Lopes, Solange Fatima Geraldo Costa, Patricia Serpa de Souza Batista, Jaqueline Brito Vidal Batista, and Amanda Maritsa de Magalhães Oliveira. 2016. Palliative Care and Spirituality: An Integrative Literature Review. Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem 69: 591–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fehring, Richard J., Judith Fitzgerald Miller, and Christine Shaw. 1997. Spiritual Well-Being, Religiosity, Hope, Depression, and Other Mood States in Elderly People Coping with Cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum 24: 663–71. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fisher, John W. 2016. Assessing Adolescent Spiritual Health and Well-Being. Social Science and Medicine—Population Health 2: 304–5. [Google Scholar]

- Frouzandeh, Nasrin, Fereshteh Aein, and Cobra Noorian. 2015. Introducing a Spiritual Care Training Course and Determining its Effectiveness on Nursing Students’ Self-Efficacy in Providing Spiritual Care for the Patients. Journal of Education and Health Promotion 4: 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giske, Tove, and Pamela H. Cone. 2012. Opening up to Learning Spiritual care of Patients: A Grounded Theory Study of Nursing Students. Journal of Clinical Nursing 21: 2006–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gommez, Rapson, and John W. Fisher. 2003. Domains of Spiritual Well-Being and Development and Validation of the Spiritual Well-Being Questionnaire. Personality and Individual Differences 35: 1975–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouveia, Maria João, Marta Marques, and José Luís Pais Ribeiro. 2009. Versão Portuguesa do Questionário de Bem-estar Espiritual (SWBQ): Análise Confirmatória da sua Estrutura Factorial. Psiologia, Saúde & Doenças 10: 285–93. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, Jennifer R., Susan K. Grove, and Suzanne Sutherland. 2017. Burns and Grove’s the Practice of Nursing Research: Appraisal, Synthesis, and Generation of Evidence, 8th ed. Grand Rapids: Elsevier, 738 p. First published 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Haase, Joan E., Nancy Kline Leidy, Doris D. Coward, Teresa Britt, and Patricia E. Penn. 2000. Simultaneous Concept Analysis: A Strategy for Developing Multiple Interrelated Concepts. In Concept Develpment in Nursing: Foundations, Techiniques and Applications. Edited by Beth L. Rodgers and Kathleen A. Knafl. Philadelphia: Saunders, pp. 209–29. First published 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Herdman, Heather T., and Shigemi Kamitsuru, eds. 2014. NANDA: NANDA International Nursing Diagnoses: Definitions and Classification 2015–2017, 10th ed. Chichester and Ames: Wiley-Blackwell, 468 p. First published 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Jahnukainen, Markku. 2011. Longitudinal Research on Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties. Emotional & Behavioural Difficulties 16: 337–38. [Google Scholar]

- Kaye, Judy, and Senthil Kumar Raghavan. 2002. Spirituality in Disability and Illness. Journal of Religion and Health 41: 231–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepherd, Laurence. 2015. Spirituality: Everyone Has It, but What Is It? International Journal of Nursing Practice 21: 566–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Shan, Jane Dixon, Guang Qiu, Yu Tian, and Ruth McCorkle. 2009. Using Generalized Estimating Equations to Analyze Longitudinal Data in Nursing Research. Western Journal of Nursing Research 31: 948–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, Marcos Venícios de Oliveira, Viviane Martins da Silva, and Thelma Leite de Araujo. 2013. Validação de Diagnósticos de Enfermagem: Desafios e Alternativas. Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem 66: 649–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McClain, Collen S., Barry Rosenfeld, and William Breitbart. 2003. Effect of Spiritual Well-Being on End-of-Life Despair in Terminally-Ill Cancer Patients. Lancet 361: 1603–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McSherry, Wilfred, Mark Gretton, Peter Draper, and Roger Watson. 2008. The Ethical Basis of Teaching Spirituality and Spiritual Care: A Survey of Student Nurses Perceptions. Nurse Education Today 28: 1002–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moberg, David O. 2002. Assessing and Measuring Spirituality: Confronting Dilemmas of Universal and Particular Evaluative Criteria. Journal of Adult Development 9: 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanasamy, Aru. 2004. Spiritual care. The Puzzle of Spirituality for Nursing: A Guide to Practical Assessment. British Journal of Nursing 13: 1140–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pesut, Barbara, Marsha Fowler, Elizabeth J. Taylor, Sheryl Reimer-Kirkham, and Richard Sawatzky. 2008. Conceptualising Spirituality and Religion for Healthcare. Journal of Clinical Nursing 17: 2803–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puchalski, Christina M. 2006. Spirituality and Medicine: Curricula in Medical Education. Journal of Cancer Education: The Official Journal of The American Association For Cancer Education 21: 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puchalski, Christina M. 2012. Spirituality in the Cancer Trajectory. Annals Oncology 23 S3: 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramezani, Monir, Fazlollah Ahmadi, Eesa Mohammadi, and Anoshirvan Kazemnejad. 2014. Spiritual Care in Nursing: a Concept Analysis. International Nursing Review 61: 211–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, Linda. 2006. Spiritual Care in Nursing: An Overview of the Research to Date. Journal of Clinical Nursing 15: 852–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothman, Juliet. 2009. Spirituality: What We Can Teach and How We Can Teach It. Journal of Religion & Spirituality in Social Work 28: 161–84. [Google Scholar]

- Severinsson, Elisabeth. 2012. Nursing Research in Theory and Practice—Is Implementation the Missing Link? Journal of Nursing Management 20: 141–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swinton, John, and Stephen Pattison. 2010. Moving Beyond Clarity: Towards a Thin, Vague, and Useful Understanding of Spirituality in Nursing Care. Nursing Philosophy: An International Journal for Healthcare Professionals 11: 226–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timmins, Fiona, and Sílvia Caldeira. 2017a. Assessing the Spiritual Needs of Patients. Nursing Standard 31: 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timmins, Fiona, and Sílvia Caldeira. 2017b. Understanding Spirituality and Spiritual Care in Nursing. Nursing Standard 31: 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timmins, Fiona, and Wilf McSherry. 2012. Spirituality: The Holy Grail of Contemporary Nursing Practice. Journal of Nursing Management 20: 951–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Cott, Alicia, and Mary C. Smith. 2009. Nursing Research: Tips and Tools to Simplify the Process. Dermatology Nursing 21: 138–40. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Van Leeuwen, René, and Bart Cusveller. 2004. Nursing Competencies for Spiritual Care. Journal of Advanced Nursing 48: 234–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Leeuwen, René, and Annemiek Schep-Akkerman. 2015. Nurses’ Perceptions of Spirituality and Spiritual Care in Different Health Care Settings in the Netherlands. Religions 6: 1346–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weathers, Elizabeth, Geraldine McCarthy, and Alice Coffey. 2016. Concept Analysis of Spirituality: An Evolutionary Approach. Nursing Forum 51: 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weaver, Kathryn, and Joanne K. Olson. 2006. Understanding Paradigms Used for Nursing Research. Journal of Advanced Nursing 53: 459–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woll, Monica L., Daniel B. Hinshaw, and Timothy M. Pawlik. 2008. Spirituality and Religion in the Care of Surgical Oncology Patients with Life-Threatening or Advanced Illnesses. Annals of Surgical Oncology 15: 3048–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Search | CINAHL | PsycINFO | MEDLINE | MedicLatina | LILACS | SciELO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S#1: nursing | 113,664 | 45,079 | 133,192 | 1077 | 9380 | 9702 |

| S#2: spirituality | 3364 | 12,111 | 4218 | 40 | 320 | 602 |

| S#3: Spiritual care | 739 | 1090 | 904 | 4 | 216 | 239 |

| S#4: S2 OR S3 | 3771 | 12817 | 4733 | 43 | 501 | 795 |

| S#5: S1 AND S#4 | 852 | 508 | 696 | 9 | 10 | 16 |

| Categories | Studies |

|---|---|

| Education | Cooper and Chang (2016); Dietmann (2016); Riklikiene (2016); Strand et al. (2016); Williams et al. (2016); Wu et al. (2016b); Chandramohan and Bhagwan (2015); Coscrato and Villela Bueno (2015); Frounzandeh et al. (2015); Linda et al. (2015); Abbasi et al. (2014); Attard et al. (2014); Lopez et al. (2014); Papazisis et al. (2014); Ross et al. (2014); Yilmaz and Gurler (2014); Cone and Giske (2013); Espinha et al. (2013); Silva et al. (2013); Tiew et al. (2013); Burkhart and Schmidt (2012); Costello et al. (2012); Giske and Cone (2012); Hsiao et al. (2012a); Sousan et al. (2012); Tiew and Drury (2012); Wu et al. (2012); Chung and Eun (2011); Nardi and Rooda (2011); Pillon et al. (2011); So and Shin (2011); Tomasso et al. (2011); Baldacchino (2010); Hsiao et al. (2010); Shores (2010); Wehmer et al. (2010); Campesino et al. (2009); Chism and Magnan (2009); Souza et al. (2009); Taylor et al. (2009); McSherry et al. (2008); Van Leeuwen et al. (2008); Lovanio and Wallace (2007); Mooney and Timmins (2007); Rankin and Delashmutt (2006); Cavendish et al. (2004); Milligan (2004); Lemmer (2002); Pesut (2002); Boutell and Bozett (1990); Fehring et al. (1987); Carson et al. (1986). |

| Management | Ross and Austin (2015); Kazemipour et al. (2012); Caldeira et al. (2011). |

| Assessment tools | Çoban et al. (2017); Hernández et al. (2017); Cruz et al. (2016); Musa and Pevalin (2016); Wu et al. (2016a); Martins (2015); Vermandere et al. (2015); Chiang et al. (2014); Freitas et al. (2013); Hsiao et al. (2013); Iranmanesh et al. (2012); Tiew and Creedy (2012); Pennapa Unsani et al. (2012); Tiew and Creedy (2012); Burkhart et al. (2011); Kreitzer et al. (2009); Van Leeuwen et al. (2009); Yoshioka et al. (2009); Delaney (2005). |

| Oncology and palliative care | Nazi et al. (2016); Rassouli et al. (2015); Tornøe et al. (2014); Wang and Hsu (2014); Gaston-Johansson et al. (2013); Khorami Markani et al. (2013); Newberry et al. (2013); Van Leeuwen et al. (2013); Au et al. (2012); Blanchard et al. (2012); Chien (2010); Murray (2010); Shih et al. (2009); Tanyi and Werner (2008); Wimmer et al. (2008); Hermann (2007); Zajec and Šolar (2007); Lundmark (2006); Meraviglia (2006); Nolan et al. (2006); Taylor (2006); Bauer-Wu and Farran (2006); Meraviglia (2004); Musgrave and McFarlane (2004a); Musgrave and McFarlane (2004b); Ferrell et al. (2003); Taylor (2003); Narayanasamy (2002); Halstead and Hull (2001); Hermann (2001); Highfield et al. (2000); Thomas and Retsas (1999); Post-White et al. (1996); Taylor et al. (1995); Taylor et al. (1994). |

| Nursing diagnosis validation | Caldeira et al. (2016); Caldeira et al. (2014); Chaves et al. (2010a); Chaves et al. (2010b); Pehler (1997). |

| Spiritual care | Ormsby et al. (2017); Chew et al. (2016); Chew et al. (2016); Cone and Giske (2016); Davoodvand et al. (2016); Haugan et al. (2016); Jun and Lee (2016); Labrague et al. (2016); Melhem et al. (2016); Minton et al. (2016); Musa et al. (2016); Musa(2016); Noome et al. (2016); Ramezani et al. (2016); Sanders et al. (2016); Wittenberg et al. (2016); Azarsa et al. (2015); Chan (2015); Giske and Cone (2015); Torskenæs et al. (2015); Wu et al. (2015); Zakaria Kiaei et al. (2015); Ødbehr et al. (2015); Baldacchino et al. (2014); Cilliers and Terblanche (2014); Jahani et al. (2014); Mesquita et al. (2014); Pfeiffer et al. (2014); Pilger et al. (2014); Taylor et al. (2014); Velásquez and Gómez (2014); Kaur et al. (2013); Ruder (2013); Rykkje et al. (2013); Taylor (2013); Tokpah and Middleton (2013); Torskenæs and Kalfoss (2013); Deal and Grassley (2012); Fouka et al. (2012); Hsiao et al. (2012b); Lin et al. (2012); Moraes Penha and Paes da Silva (2012); Palencia and Durán de Villalobos (2012); Ponte et al. (2012); Leguía and Priet (2012); Van Dover and Pfeiffer (2012); Yang et al. (2012); Carron and Cumbie (2011); Chaves et al. (2011); Dhamani et al. (2011); Kim et al. (2011); Liu et al. (2011); McSherry Jamieson (2011); Nabolsi and Carson (2011); Vlasblom et al. (2011); Walulu and Gill (2011); Wu and Lin (2011); Chan (2010); Lundberg and Kerdonfag (2010); Mahmoodishan et al. (2010); Pedrão and Beresin (2010); Bailey et al. (2009); Dunn et al. (2009); Pehler and Craft-Rosenberg (2009); Wu et al. (2009); Baldacchino (2008); Burkhart and Hogan (2008); Carr (2008); Christensen and Turner (2008); McLeod and Wright (2008); Herrera (2008); Wong et al. (2008); Cavendish et al. (2007); Chung et al. (2007); Creel (2007); Hsiao et al. (2007); Koslander and Arvidsson (2007); Litwinczuk and Groh (2007); Van Dover and Pfeiffer (2007); Wallace and O’Shea (2007); Yanga and Maob (2007); Baldacchino (2006); Black et al. (2006); Cavendish et al. (2006); Chan et al. (2006); Hubbell et al. (2006); Mordiffi (2006); McSherry (2006); Ray and McGee (2006); Belcher and Griffiths (2005); Koslander and Arvidsson (2005); Lundmark (2005); Kociszewski(2004); Ormsby and Harrington (2004); Lowry and Conco (2002); Waltson(2002); Carroll (2001); Cavendish et al. (2001); MacKinlay (2001a); MacKinlay (2001b); Narayanasamy and Owens (2001); Sellers (2001); Tuck et al. (2001); Cavendish et al. (2000); Tongprateep (2000); Castellaw et al. (1999); Kohler (1999); Shih et al. (1999); Ross (1997); Hungelmann et al. (1996); Pullen et al. (1996); Bauer and Barron (1995); Clark and Heidenreich (1995); Harrington (1995); Valopaasi et al. (1995); Burkhardt (1994); Burkhardt (1993); Zerwekh (1993); Soeken and Carson (1986). |

| Research Paradigm | Methodology | Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Quantitative | Observational descriptive | Çoban et al. (2017); Hernández et al. (2017); Caldeira et al. (2016); Cruz et al. (2016); Haugan et al. (2016); Labrague et al. (2016); Melhem et al. (2016); Musa et al. (2016); Riklikiene (2016); Sanders et al. (2016); Williams et al. (2016); Wu et al. (2016a); Wu et al. (2016b); Chan (2015); Chandramohan and Bhagwan (2015); Martins (2015); Wu et al. (2015); Zakaria Kiaei et al. (2015); Abbasi et al. (2014); Attard et al. (2014); Caldeira et al. (2014); Chiang et al. (2014); Jahani et al. (2014); Lopez et al. (2014); Mesquita et al. (2014); Papazisis et al. (2014); Ross et al. (2014); Freitas et al. (2013); Hsiao et al. (2013); Kaur et al. (2013); Newberry et al. (2013); Ruder (2013); Silva et al. (2013); Tiew et al. (2013); Blanchard et al. (2012); Iranmanesh et al. (2012); Leguía and Priet (2012); Tiew and Creedy (2012); Pennapa Unsani et al. (2012); Wu et al. (2012); Burkhart et al. (2011); Caldeira et al. (2011); Chaves et al. (2011); McSherry and Jamieson (2011); Nardi and Rooda (2011); Pillon et al. (2011); Tomasso et al. (2011); Wu and Lin (2011); Chan (2010); Chaves et al. (2010a); Chaves et al. (2010b); Murray (2010); Pedrão and Beresin (2010); Shores (2010); Campesino et al. (2009); Dunn et al. (2009); Kreitzer et al. (2009); Van Leeuwen et al. (2009); Wu et al. (2009); Yoshioka et al. (2009); Herrera (2008); Wong et al. (2008); Hermann (2007); Hsiao et al. (2007); Litwinczuk and Groh (2007); Zajec and Šolar (2007); Wallace and O’Shea (2007); Chan et al. (2006); Hubbell et al. (2006); Lundmark (2006); Meraviglia (2006); Ray and McGee (2006); Taylor (2006); Bauer-Wu and Farran (2005); Belcher and Griffiths (2005); Delaney (2005); Lundmark (2005); Milligan (2004); Musgrave and McFarlane (2004a); Lemmer (2002); Pesut (2002); Tuck et al. (2001); Highfield et al. (2000); Castellaw et al. (1999); Pehler (1997); Hungelmann et al. (1996); Taylor et al. (1995); Taylor et al. (1994); Boutell and Bozett (1990); Carson et al. (1987); Soeken and Carson (1986). |

| Observational correlational | Chew et al. (2016); Jun and Lee (2016); Musa and Pevalin (2016); Musa (2016); Azarsa et al. (2015); Gaston-Johansson et al. (2013); Hsiao et al. (2012); Kazemipour et al. (2012); Palencia and Durán de Villalobos (2012); Kim et al. (2011); Chism and Magnan (2009); McSherry et al. (2008); Chung et al. (2007); Yanga and Maob (2007); Black et al. (2006); Meraviglia (2004); Musgrave and McFarlane (2004b); Pullen et al. (1996); Fehring et al. (1987). | |

| Quasi-experimental | Yilmaz and Gurler (2014); Costello et al. (2012); Hsiao et al. (2012a); Taylor et al. (2009); Van Leeuwen et al. (2008); Lovanio and Wallace (2007); MacKinlay (2001b). | |

| Experimental | Frouzandeh et al. (2015); Burkhart and Schmidt (2012); Chung and Eun (2011); Vlasblom et al. (2011). | |

| Qualitative | Descriptive | Cooper and Chang (2016); Davoodvand et al. (2016); Dietmann (2016); Nazi et al. (2016); Ramezani et al. (2016); Strand et al. (2016); Wittenberg et al. (2016); Coscrato and Villela Bueno (2015); Rassouli et al. (2015); Baldacchino et al. (2014); Velásquez and Gómez (2014); Espinha et al. (2013); Khorami Markani et al. (2013); Au et al. (2012); Fouka et al. (2012); Lin et al. (2012); Moraes Penha and Paes da Silva (2012); Ponte et al. (2012); Yang et al. (2012); Dhamani et al. (2011); Liu et al. (2011); Chien (2010); Hsiao et al. (2010); Mahmoodishan et al. (2010); Bailey et al. (2009); Wimmer et al. (2008); Cavendish et al. (2007); Mooney and Timmins (2007); Cavendish et al. (2006); Nolan et al. (2006); Rankin and Delashmutt (2006); Taylor (2003); Cavendish et al. (2001); Hermann (2001); Post-White et al. (1996); Clark and Heidenreich (1995); Harrington (1995); Burkhardt (1993); Zerwekh (1993). |

| Descriptive and exploratory | Noome et al. (2016); Linda et al. (2015); Ross and Austin (2015); Pilger et al. (2014); Torskenæs and Kalfoss (2013); Van Leeuwen et al. (2013); Tiew and Drury (2012); Sousan et al. (2012); Lundberg and Kerdonfag (2010); Wehmer et al. (2010); Souza et al. (2009); Halstead and Hull (2001); Narayanasamy and Owens (2001). | |

| Descriptive and reflection | Baldacchino (2010). | |

| Descriptive and comparative | Torskenæs et al. (2015). | |

| Descriptive and correlational | Bauer and Barron (1995). | |

| Phenomenology | Ormsby et al. (2017); Ødbehr et al. (2015); Cilliers and Terblanche (2014); Pfeiffer et al. (2014); Taylor et al. (2014); Tornøe et al. (2014); Rykkje et al. (2013); Tokpah and Middleton (2013); Deal and Grassley (2012); Nabolsi and Carson (2011); So and Shin (2011); Pehler and Craft-Rosenberg (2009); Shih et al. (2009); Carr (2008); Christensen and Turner (2008); McLeod and Wright (2008); Tanyi and Werner (2008); Creel (2007); Koslander and Arvidsson (2007); Mordiffi (2006); Koslander and Arvidsson (2005); Kociszewski (2004); Lowry and Conco (2002); Narayanasamy (2002); Carroll (2001); Tongprateep (2000). | |

| Grounded theory | Giske and Cone (2015); Wang and Hsu (2014); Cone and Giske (2013); Giske and Cone (2012); Van Dover and Pfeiffer (2012); Walulu and Gill (2011); Burkhart and Hogan (2008); van Dover and Pfeiffer (2007); McSherry (2006); Waltson (2002); MacKinlay (2001a); Cavendish et al. (2000); Thomas and Retsas (1999); Burkhardt (1994). | |

| Ethnographic | Ferrell et al. (2003); Sellers (2001). | |

| Pilot study | Ross (1997). | |

| Phenomenology and Grounded theory | Carron and Cumbie (2011). | |

| Mixed Methods | Cone and Giske (2016); Minton et al. (2016); Vermandere et al. (2015); Taylor (2013); Baldacchino (2008); Baldacchino (2006); Cavendish et al. (2004); Ormsby and Harrington (2004); Kohler (1999); Shih et al. (1999); Valopaasi et al. (1995). | |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martins, H.; Romeiro, J.; Caldeira, S. Spirituality in Nursing: An Overview of Research Methods. Religions 2017, 8, 226. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel8100226

Martins H, Romeiro J, Caldeira S. Spirituality in Nursing: An Overview of Research Methods. Religions. 2017; 8(10):226. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel8100226

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartins, Helga, Joana Romeiro, and Sílvia Caldeira. 2017. "Spirituality in Nursing: An Overview of Research Methods" Religions 8, no. 10: 226. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel8100226

APA StyleMartins, H., Romeiro, J., & Caldeira, S. (2017). Spirituality in Nursing: An Overview of Research Methods. Religions, 8(10), 226. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel8100226