Abstract

This study utilized participatory action research approaches to construct a follower-centric framework for measuring influences on sexual decision making by youth members of a church organization. Participants were Batswana Pentecostal church members self-reporting on their engagement in pre-marital sex (n = 68, females = 62%; age range 15–23 years; median age = 20.3 years) from eight of 26 randomly selected congregations. They completed a multi-stage concept mapping process that included free listing of statements of potential influences on their sexual decisions. They then sorted the statements into groupings similar in meaning to them, and rated the same statements for relative importance to their sexual decisions. Multidimensional scaling and hierarchical cluster analysis of the data yielded a five cluster solution in which church teachings emerged as most salient to the teenagers’ sexual decision making followed by future orientation, community norms, knowledge about HIV/AIDS and prevention education. While the youth believed to be influenced by religion teachings on primary sexual abstinence, they self-reported with pre-marital sex. This suggests a need for secondary abstinence education with them to reduce their risk for STIs/HIV and unwanted pregnancies. Concept mapping is serviceable to construct frameworks and to identify content of follower-centric influences on sexual decision making by church youth members.

1. Introduction

Religion organizations hold beliefs about a personal relationship with a higher power or God to influence the behavior of followers [1,2]. The typical religion organization socializes followers to adhere to faith-aligned teaching; and adoption of the teachings by the followers has implications for their health related decisions [1,3,4]. These religion aligned values are often communicated implicitly as well as explicitly to define what qualifies for a follower of “good standing” in one’s public and private conduct [5,6,7,8,9,10]. However, follower member decisions about sexual behavior may be personal and private, while also influenced by religion organization teachings among religion followers. For instance, religion aligned teachings typically endorse primary sexual abstinence-until marriage or being faithful in a consummated relationship [11,12]. Nonetheless, potentially competing secular or private personal values held by religion organization followers might influence in unknown ways how they frame influences of their sexual decisions [13]. Developing follower-centric measures with religion organization members has the potential to map their framing of sexual decisions in the face of potentially competing religion and personal-secular values. Follower-centric health promotion frameworks are those with content items freely generated by organization members rather than sourced from existing instruments from literature review. For that reason, follower-centric approaches are likely to tap into their private framing of sexual decisions with religion more credibly than alternative methods. This study applied a follower-centric approach to understanding influences on sexual decision making by teenagers of a Pentecostal faith community in Botswana, a high HIV pandemic country.

2. Pentecostal Churches in Botswana

Botswana is a sub-Southern African country that borders Angola, Namibia, South Africa, Zambia and Zimbabwe. It has an estimated 20 percent HIV-positive prevalence rate, which ranks among the highest HIV infection rates in the world. The incidence of HIV is around 23% among the 15–19 year olds and close to 44% among the youths aged 20 and 24 years [14], placing the youth of that country at critical risk from HIV morbidity and mortality.

Pentecostal churches comprise 73% of faith-based organizations (FBOs) in the country, and are the majority faith community churches [15], enrolling about 80% of community youths in the country [16]. Historically, the Pentecostal church community in Botswana emphasized (A) abstinence-only-until-marriage for the youths and (B) being faithful to one’s partner in marriage [16,17,18], and is increasingly open to a variety of sexual health protection teachings, including HIV prevention [19]. Nonetheless, HIV/STI prevention and care support interventions with the Botswana Pentecostal church youth would require evidence-informed follower-centric indicators responsive to their unique HIV prevention support needs as faith community members.

3. Interpretive Health Decisions

Most health promotion approaches with faith communities presume member adoption of the official religion doctrine, and focus on the extent to which religion organization members endorse faith-based precepts to guide their behavior [11,20]. Such approaches overlook the fact that faith community members likely engage in interpretive processes to overlay their faith based beliefs on personal/secular values resulting in adapted sexual decision making [21]. Followers with adapted sexual decision making likely recognize the role of both faith and personal/secular value influences on their sexual health practices. If member followers experienced decisional tension from competing religion and personal value dissonance, they might act to adaptively reduce the tension by framing personal-secular influences from the viewpoint of religion [7,22,23,24] or recognizing the significance of both religion or personal value aligned influences [13,19,25]. Follower-centric measures would map both the components and salience of sexual decision influences among faith community teenagers true to them.

Previous studies [13,26] reported church community members prioritize religion to secular community influences on their sexual decision making overall; although the effect was comparatively weaker among those who had engaged in their first sexual experience as compared to those with primary abstinence [13]. Pentecostal church youth would require evidence-informed follower-centric measures responsive to their unique HIV prevention support needs as faith community members.

Primary abstinence refers to not having any history of penetrative sex. This is in contrast to secondary abstinence in which individuals elect to refrain for penetrative sex following sexual debut or a history of prior penetrative sex. The church youths who engaged in premarital sex seemed to also prioritize religion abstinence oriented teachings on their sexual decisions comparatively less often than did peers with primary sexual abstinence [13]. This places these youth at higher risk for STI/HIV and unwanted pregnancies in the absence of sexual decisions for secondary abstinence. Furthermore, a history of premarital sex by church youth does present a conundrum for them in terms of the abstinence messages received and the translation of those messages to actual practice. Youth who engage in premarital sex are conceivably at elevated risk for secondary abstinence relapse primed by the prior sexual experience and also the glamorization of sex by secular social media.

The validation of follower-centric frameworks for influences on sexual decisions among church youths for whom secondary abstinence is a priority would be important for HIV prevention and care support with faith community organizations [2,21]. Follower-centric frameworks for health promotion developed with church community youth would help address the question of what messages they perceive to receive and how to interpret them for health support interventions.

4. Goals of the Study

The study utilized concept mapping participatory approaches to develop a follower-centric framework of sexual decision influences of importance for Batswana Pentecostal church teenager members with self-reported history of pre-marital sex. Their choice and prioritization of sexual decision influences would allow for the scoping of priority considerations to optimize STI/HIV and unwanted pregnancy prevention interventions with them. A related goal was to map any differences in the prioritization of sexual decision making framework components by gender of participants since female youths in Botswana have earlier sexual debut than males.

Religion organizations increasingly are key partners in the sustenance and promotion of public health initiatives, and what they transmit to the membership is important to how members use public health services [27,28,29]. Understanding sexual decision making by faith community teenagers who might be actively exploring their sexuality would be important for public health education with faith community members [13].

5. Method

5.1. Participants and Setting

The data are from a larger study on aspects of religion that influence HIV prevention among Batswana teenagers [13]. Only the data from teenagers who self-reported as unmarried and who had engaged in pre-marital sex (N = 68; females 62%; age range 15–23 years; median age 20.3 years) were considered for the measure framing development study (see Table 1). The study sample was drawn from eight of 26 congregations and with a total enrollment of 265 youth members, about 75% of whom self-reported no sexual debut. Participant youths were unique from having engaged in pre-marital sex contrary to church teachings on abstinence-until-marriage. The teenagers self-reported on frequency of sexual activity (have you had first sexual intercourse; how long is it since last sexual intercourse) and also length of time affiliated with church and congregation (in months). The question, “How long since last sex” was a proxy variable for secondary abstinence the longer since last sex, the greater the likelihood that the individual youth would refrain from sexual activity assuming opportunity.

Table 1.

Study sample characteristics (N = 68).

From these data it would seem that a high proportion of the teenagers in the secondary abstinence category (n = 44; 64.7%) from their reporting that they had sex several months ago. A significant proportion of the church youths (n = 24; 35.3%) self-reported with relatively recent sexual activity (less than a month ago). Staying abstinent for several months would, if true, suggest a successful decision by the youth not to engage in sex with opportunity. This would further suggest their realigning sexual behavior to church abstinence teachings as befitting of their earned “good” church followership. The teenage followers were also relatively new to the Pentecostal church congregation or organization (about 6 months) which might suggest a high mobility of youths among the faith communities in Botswana.

5.2. Procedure and Data Collection

The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics review boards of the University of Sydney and the University of Botswana. Parents consented for their minor children who were minors to take part in the study. The teenagers individually assented to the study. The study aims were described to them, their rights as participants explained, including the fact that they could withdraw from the study without penalty.

Data were collected at the local church center and during normal church activity hours. Data were collected in two workshops at each of the church centers: (1) brainstorming of sexual decision statements; and (2) sorting of those statements for similarity or coherence and then rating of the statements for importance. The procedure for the data collection is described next in chronological order.

5.2.1. Brainstorming Workshop

The brainstorming work involved participants who self-identified as having engaged in premarital sex on de-identified information sheet. Th participants were then asked:

“Think about an HIV/AIDS prevention message to prevent [you] from contracting HIV. As you think about these issues, please generate as many statements (short phrases or sentences) as you can and list them below.”

About half of the teenagers were probed on their sexual decisions with the stem “Based on my faith or beliefs” and the remainder with the stem “Based on my personal beliefs”. The participants used an information blank with instructions for them to list five to 10 indicator statements for their sexual decision making for STI/HIV prevention

Participants self-selected a data de-identifier which they used on the statement probes for completing the concept mapping activities (as described below) so that their contributed data could not be traced to them individually. The church youths placed their written submission in unmarked envelops, which they then deposited in a common box in the same room guaranteeing anonymity of the data.

Content analysis of the statement submissions by the project assistants yielded fifty unique statements from the brainstorming session. A high Kendall’s tau co-efficient of agreement of 0.89 between statement listing by probe group (i.e., “Based on my faith or beliefs” and “Based on my personal beliefs”) was evidence for the statement to be sorted and rated as one composite listing. Each of these were captured on separate 3″ × 5″ cards for sorting by the teenagers into clusters of meaning to them as follows:

5.2.2. Sorting of the Statements

For the statement sorting phase, each participant was provided with a bundle of cards with numbered individual statements from the brainstorm session and asked to group the statements into piles, “in a way that make sense to you”. Each participant was asked to write the number for each statement on a record sheet so that statements grouped together were in the same thematic cluster from the perspective of the individual church youth. The participants also provided a short descriptive label for each statement grouping for common meaning they perceived. The 50 statements from the brainstorming were reproduced onto a survey format for rating as follows:

5.2.3. Rating of Statements

The participants rated each of the statements for relative importance to their sexual decisions for HIV prevention on a 5-point Likert-type scale (relatively unimportant = 1, to extremely important = 5). They used the same self-assigned data identifiers that they used for the brainstorming and sorting phases allowing for the matching of the data from the individual participants for the data analysis.

6. Data Analysis

The data were analyzed using Concept Systems software [30], a program that applies multidimensional scaling (MDS) and Hierarchical Clustering analysis (HCA) to structure free listed data (with sorting and rating) into aggregated statement clusters. Its output includes descriptive statistics that are usable for further analyses. The MDS function of Concept Systems locates statements judged to be similar by the participants more proximately than those that are piled together less frequently. Concept Systems then overlays importance ratings (1–5) onto the proximity configuration from the MDS (as previously described) using HCA. From these analyses, statement item means within clusters are computed based upon the importance ratings by the participants. Concept Systems also generates measures for the reliability of scores by cluster. The reliability indices computed by the software are internal consistency alpha for scores within a cluster grouping. Concept system also generates alternative cluster labels from those suggested by the participants from their statement sorting groupings.

7. Results

Five cluster groupings of statements resulted from the MDS statement sorting analysis (as previously described) of influences on sexual decisions for HIV prevention by the teenagers who had engaged in pre-marital sex while church members: Biblical perspectives, Future Focus, Community Norms, Facts about HIV and AIDS, and Prevention Education (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Statements By Cluster (with Importance Summary Statistics) for Influences on Sexual Decision Making with Religion and First Sex (N = 68).

7.1. Religion Influences

The Biblical perspectives cluster (9 items, α = 89) comprised sexual decision indicators premised on following church teachings that would prevent contracting HIV. Within this clustering, a Trusting relationship with God was most highly endorsed (Mean = 4.69), Say no to sex before marriage (Mean = 4.63) and Asking God for a partner and waiting for marriage (Mean = 4.56). The more belief aligned statements were comparatively lower ranked within the cluster (Mean 3.60 for Your spirit, soul and body should be blameless to Mean = 4.35 for Hold on to faith and a good conscience). Although the statement Abstain from sex would align well with the Prevention education cluster, the church youth clustered it as part of church teachings, so it is listed within the Biblical perspective cluster.

7.2. Secular Influences

The Future Focus cluster comprised statements on setting and pursuing long-term life goals (13 items; α = 0.92). For the most part the future focus oriented statement items were behaviorally anchored around personal development (Mean = 4.12 for Taking responsibility for one’s future, to Mean = 4.37 for Being careful with your lifestyle). The important cluster on managing relationships rated comparatively lower (Mean = 3.47 for Books before boys or girls; to 4.08 for School first, sex later). Although statements such as Resist negative peer pressure and Choose friends wisely would also relate to the Community norms, they were sorted by the participants to belong to the Future focus cluster.

The Community norms statements captured the sexual decision indicators that the teenagers perceived to be true of the general population or secular others, which also would be important to their HIV prevention behavior (7 items, α = 87). The church youths perceived these indicators to coalesce around health-related quality of life in their communities inclusive of healthy living (Mean = 4.39), community health supports (Mean = 3.51), Peers, family, teachers (Mean = 4.26), and valuing teenage development education (Adolescence and puberty: Mean = 3.00; and understanding the Consequences of Unwanted pregnancies: Mean = 3.42).

The Facts about HIV and AIDS statements cluster (12 items; α = 0.86) referred to knowledge of HIV and AIDS as disease conditions (3 items), including prevention and treatment care support (5 items) and living well with HIV and AIDS (4 items). By order of importance ratings the teenagers generally rated scientific knowledge about HIV and AIDS relatively higher (Link between STD and HIV and AIDS: Mean = 3.53; to Sexually Transmitted Infections: Mean = 4.14) than they did knowledge about living well with HIV and AIDS (Be open about your HIV status: Mean = 2.72; Living with HIV = 3.15). The Prevention Education statements cluster included items related to risk reduction from social networks (Mean = 2.83 for Cultural practices that promote the spread of HIV and AIDS, to Mean = 4.23 for Avoid places with risks for bad abuse). Aspects of contraception use (Proper use of contraceptives: Mean = 3.13; Limits of condoms and contraceptives: Mean = 2.25) were recognized within the Prevention Education cluster.

7.3. Sexual Decision Framing by Gender

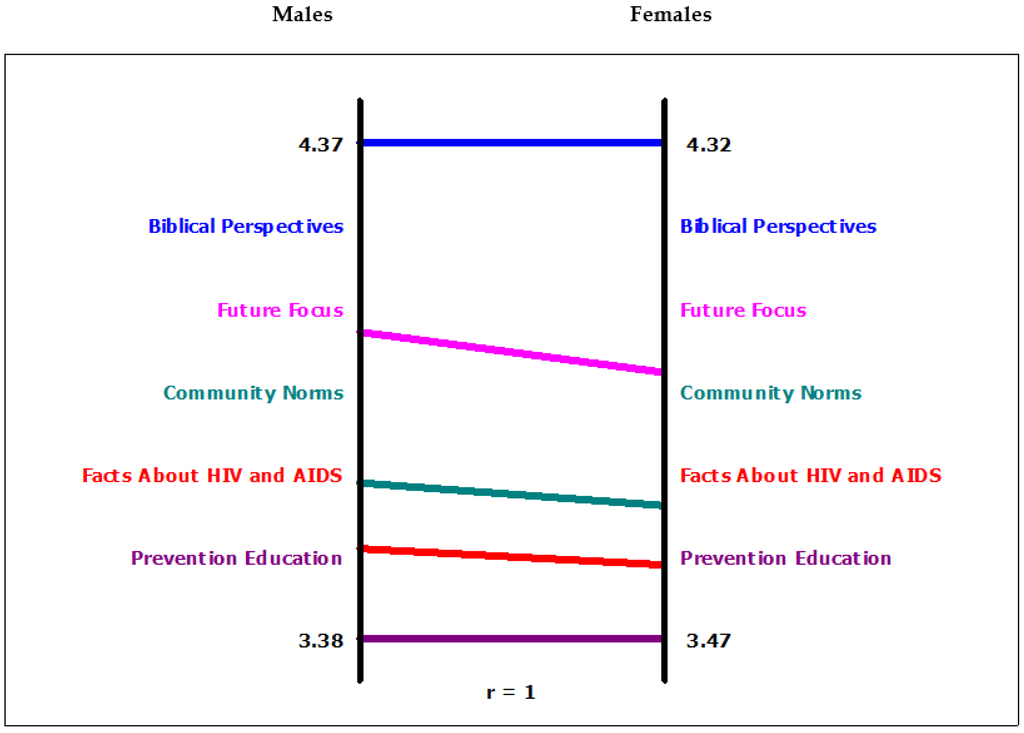

Concept mapping pattern map analysis results indicated perfect agreement (r = 1.00) by gender in the importance rating ordering of influences on the youth’s sexual decisions (see Figure 1). Pattern analysis using concept mapping calculates a correlation in the relative ordering of the aggregated cluster scores.

Figure 1.

Pattern map for concordance of agreement between males and females with first sex in their framing and prioritization of influences on their sexual decision making. Note the numbers on the vertical axis are mean group scores.

8. Discussion

The follower-centric sexual health promotion development approach implemented with Pentecostal faith church community youths yielded a framework of influences on their sexual decision comprising both religion (i.e., Biblical perspectives) and personal-secular (Future focus, Community norms, Prevention education, Facts about HIV and AIDS). Findings are consistent with those of previous studies [13,26], adding to the literature regarding the likely reproducibility of the influence clusters with other church youth samples from within the Christian faith community. To the best of our knowledge, this is one of three studies with teenagers to have used mixed methods concept mapping approaches to develop prospective measures usable to construct HIV prevention intervention with youth in a sub-Saharan country setting. The other studies [13,26] sampled youth participants reporting no sex or from an evangelical church organization. This study sampled a larger number of youth who self-reported sex debut compared to previous studies, allowing for a firmer understanding of how sexually active youth frame premarital sexual activity in the context of health promotion with church followership.

Several advantages follow from applying follower-centric approaches to study influences on sexual decisions by church youth in a predominantly secular country setting. These include the fact that church youth perceive that religion perspectives and several other non-faith influences matter to their HIV prevention. This puts to rest the presumption that only Biblical teachings would influence sexual decisions among church youth. In addition, the resulting influence clusters (a) provide reliable and valid information for informing the appropriate mixture of religion and secular components in health support interventions with sexually active church congregants; (b) are credible with the follower-ship and other key faith community decision makers for adoption in their HIV prevention support intervention with the faith community members; and (c) are cost-effective in that the methodology can be used with other similar faith organizations with relatively minor adaptations.

A participatory sexual health promotion framework development approach as utilized in this study goes a long way towards proactively addressing likely concerns by followers of a religion organization regarding the source and legitimacy of the knowledge base for HIV prevention support interventions that they would consider for adoption. The follower-centric influences framework development effort presented here is limited in that it represents a small sample of teenagers who self-reported premarital sex. One limitation of the findings of the study is the fact that some who reported abstinence from sex may not have self-reported accurately due to social desirability effects. For these reasons, the findings only suggest possible reasons for sexual debut, and the study should be replicated with a larger study sample with differentiation by extent of sexual activity, time associated with religion organization followership, and personal religiosity (degree and level of involvement with religion practices). Findings from such a study would enable cross-validation of the sexual decision making influence frameworks and the content that operationalizes them within clusters of sexual experience (sexually active; with secondary abstinence), religion affinities (new and transitional membership, long-term membership), and personal religiosity. Future focus is both a secular and religion-influenced value [13] suggesting its robust importance to influencing health behavior regardless of faith affiliation [31,32].

The importance ranking data between and within influence clusters might be interpreted to characterize both the salience and endorsability of the clusters and content by the church youths who reported premarital sex. However, from a measurement perspective, item content endorsed to be of lower importance may differentiate more among sexual decision statuses than those with higher endorsement. This might be explained by the fact that within influence cluster those with low endorsement likely tap into personal value influence choices more proximal to the decision to be adopted while those with higher endorsement might represent religion or secular dogma positions rather distal to decisional choice points [33]. Rasch calibration of items within clusters would provide evidence on item-person separation or differentiation reliability [34] allowing for selection of rich information items for constructing shorter and efficient measures of sexual decision influences by church youths with sexual experience.

Various explanations are possible as to how and why the church youth can hold in their awareness (and likely with sincerity) all sorts of community and faith-based belief systems but then act in completely opposite ways from their beliefs. For instance, there is evidence to suggest that the reward sensitive neural pathways of the ventral striatum and orbito-frontal cortex are hyper-responsive to social reward seeking at the adolescent development stage compared to adulthood [35,36]. That being the case, then the new-found emotions of sexual desire and wanting to belong are so much stronger than the old, concrete thinking of “you should not” because God, your community (avoid sex networks), your family (you will cause us social shame with premarital sex) will think less of you. They might think they would be forgiven for sexual indulgence by a kind and merciful God (“How can something that feels so good be so bad?” they might reason). Teenagers are also known to be with wider dissonance tolerance than adults so they can present with contrasting behaviors that they both hold to be true of them [37].

A way to challenge this dissonance is to have adolescents “act out/role play” the conversation in their heads with each other to promote secondary sexual abstinence behaviors with disruption of reward seeking impulses. The youth might find strength from hearing that others share their confusion and ambivalence the strong urge to sexually indulge which would be against church abstinence teachings. By talking aloud about their commitment to secondary sexual abstinence in the face of urges to self-reward with sexual engagement, they may develop the skills for reasoning out the pros and cons of their decisions. This means faith-based youth leaders must be open to hearing that young people have sexual desires and a strong need to belong to something/someone other than the church and working through the contradictions in a supportive, positive way.

9. Conclusions

In conclusion, the evidence from follower-centric construction of influences on sexual decisions by church youth suggests a need to promote secondary abstinence as a HIV prevention strategy. This would entail supporting church youth to remain in good standing in their faith community while committing to sexual decisions that minimize their sexual health risks inclusive of secular teachings. Such a strategy would build on the youth’s understanding of influences on their sexual decision choices from their faith beliefs and also from community norms of significance to them.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded in part by a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health (R21 HD 061021; Elias Mpofu, PI). The content is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development or the National Institutes of Health. The author wishes to acknowledge the participants for their collaboration, and Kayi Ntinda and Fidelis Nkomazana for assistance with the data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Elva M. Arredondo, John P. Elder, Guadalupe X. Ayala, and Nadia R. Campbell. “Is Church attendance associated with Latinas’ Health practices and self-reported health? ” American Journal of Health Behavior 29 (2005): 502–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laurie J. Bauman, and Rebecca Berman. “Adolescent relationships and condom use: Trust, love and commitment.” AIDS and Behavior 9 (2005): 211–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenda R. Jackson, and Cindy S. Bergeman. “How does religiosity enhance well-being? The role of perceived control.” Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 3 (2011): 149–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monica M. McKenzie, Naomi M. Modeste, Helen Hopp Marshak, and Colwick Wilson. “Religious involvement and health-related behaviors among Black Seventh-Day Adventists in Canada.” Health Promotion Practice 16 (2014): 264–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louis Brenner. Controlling Knowledge: Religion, Power and Schooling in a West African Muslim Society. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Jesse Graham, and Jonathan Haidt. “Beyond beliefs: Religions bind individuals into moral communities.” Personality and Social Psychology Review 14 (2010): 140–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefan Huber, and Odilo W. Huber. “The Centrality of Religiosity Scale (CRS).” Religions 3 (2012): 710–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ara Norenzayan, and Azim F. Shariff. “The origin and evolution of religious prosociality.” Science 332 (2008): 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacy G. McNamee. “Faith based organizational communication and its implications for member identity.” Journal of Applied Communication Research 39 (2011): 422–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassilis Saroglou. “Religiosity, bonding, behaving and belonging: The big four religious dimensions and cultural variation.” Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 42 (2011): 1320–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christine Kim, and Robert Rector. “Evidence on the Effectiveness of Abstinence Education: An Update.” 2010. Available online: www.heritage.org/Research/Abstinence/bg2372.cfm (accessed on 4 November 2012).

- Elias Mpofu, Tinashe Moira Dune, Denise Dion Hallfors, John Mapfumo, Magen Mutepfa, and James January. “Apostolic faith organization contexts for health and wellbeing in women and children.” Ethnicity and Health 13 (2011): 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elias Mpofu, Fidelis Nkomazana, Jabulani A. Muchado, Lovemore Togarasei, and Jeffrey B. Bingenheimer. “Faith and HIV prevention: The Conceptual framing of HIV prevention among Pentecostal Batswana Teenagers.” BMC Public Health 14 (2014): 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO/UNAIDS/UNICEF. Global AIDS Epidemic. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Botswana Christian Council (BCC). Report: Adolescent Sexual Reproductive Health Survey. Gaborone: Botswana Christian Council, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Musa W. Dube, ed. HIV/AIDS and the Curriculum: Methods of Integrating HIV/AIDS in Theological Programs. Geneva: World Council of Churches, 2003.

- Musa Dube. Africa Praying: A Handbook on HIV/AIDS Sensitive Sermon Guidelines and Liturgy. Geneva: World Council of Churches, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lovemore Togarasei, Sana K. Mmolai, and Fidelis Nkomazana. The Faith Sector and HIV/AIDS in Botswana: Responses and Challenges. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lovemore Togarasei. “The Pentecostal gospel of prosperity in African Contexts of poverty.” Exchange 40 (2011): 335–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John B. Jemmott III, Loretta S. Jemmott, and Goeffrey T. Fong. “Efficacy of a theory-based Abstinence-only intervention Over 24 Months.” Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine 164 (2010): 152–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenn Anderson. “Vanity vs. Gluttony: Competing Christian discourses on personal health.” Journal of Applied Communication Research 39 (2011): 370–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrea D. Clements, and Anna V. Ermakova. “Surrender to God and stress: A possible link between religiosity and health.” Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 4 (2012): 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian Zwingmann, Constantin Klein, and Arndt Bussing. “Measuring religiosity/spirituality: Theoretical differentiations and categorization of instruments.” Religions 2 (2011): 345–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias Mpofu, Denise Dion Hallfors, Magen M. Mutepfa, and Tinashe M. Dune. “Sexual decision making as perceived by Zimbabwean orphan girl students.” Journal of Mixed Methods Research 8 (2014): 363–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sue Aford, and Marilyn Keefe. “Abstinence only-until-marriage programs: Ineffective, unethical and poor public health.” 2007. Available online: www.advocatesyouth.org (accessed on 4 November 2012).

- Elias Mpofu, Magen Mhaka Mutepfa, and Denise Hallfors. “Mapping structural influences on sex and HIV education in church and secular schools in Zimbabwe.” Evaluation and the Health Professions 35 (2012): 346–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beverly Haddad, ed. Religion and HIV and AIDS: Charting the Terrain. Pietermaritzburg: UKZN Press, 2011.

- Jenny Trinitapoli, and Alexander Weinreb. Religion and AIDS in Africa. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Derek M. Griffith, Bettina Campbell, Julie Ober Allen, Kelvin J. Robinson, and Sarah Kretman Stewart. “YOUR blessed health: An HIV-prevention program bridging faith and public health communities.” Public Health Reports 125 (2010): 4–32. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Concept Systems Incorporated. Concept Systems. Ithaca: Concept Systems Inc., 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Evan C. Carter, Michael E. McCullough, Jungmeen Kim-Spoon, Carolina Corrales, and Adam Blake. “Religious people discount the future less.” Evolution and Human Behavior 33 (2012): 224–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher Ellison, and Daisy Fan. “Daily spiritual experiences and psychological well-being Among US Adults.” Social Indicators Research 8 (2008): 247–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias Mpofu, and Thomas Oakland. “Assessment of Value Change in Adults with Acquired Disabilities.” In Clinician’s Handbook of Adult Behavioral Assessment. Edited by Michel Hersen. New York: Elsevier Press, 2006, pp. 601–30. [Google Scholar]

- Steven J. Osterlind, Elias Mpofu, and Thomas Oakland. “Item response theory and computer adaptive testing.” In Rehabilitation and health assessment: Applying ICF guidelines. Edited by Elias Mpofu and Thomas Oakland. New York: Springer Publishing Company, 2010, pp. 95–119. [Google Scholar]

- Adriana Galvin. “Adolescent development of the reward system.” Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 4 (2010): 116–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raymundo Baez-Mendoza, and Wolfram Schultz. “The role of the striatum in social behaviour.” Frontiers in Neuroscience 7 (2013): 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ty A. Ridenour, Linda L. Caldwell, Douglas D. Coatsworth, and Melanie A. Gold. “Directionality between tolerance of deviance and deviant behaviour is age-moderated in chronically stressed youth.” Journal of Child Adolescnece Sunstance Abuse 2 (2011): 184–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2016 by the author; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).