1. Introduction

When congregations seek to address social needs, they often pursue this goal through acts of service and political engagement. Their service provision typically aims to provide short-term relief through meeting the immediate needs of individuals, whereas their political participation often aims to produce long-term solutions by advocating for policies to improve social conditions. Over the past three decades, a tremendous amount of research has been dedicated to analyzing congregation-based service provision and political participation. However, little is known about how congregations’ involvement in these arenas has changed during this period

1. To help fill this gap, this study analyzes three waves of data from a national survey of congregations to assess how congregations’ participation patterns in service-related and political activities have been changing since the 1990s.

The analysis indicates that between 1998 and 2012 the percentage of congregations involved in service-related activities has been increasing, while the percentage of congregations participating in political activities has been decreasing. By 2012, twice as many congregations were participating in service-related activities than political activities. The analysis also examines participation trends among subpopulations of congregations grouped by their religious tradition, ethnoracial composition, and ideological orientation. With regard to general involvement in service-related activities, the participation rate among every type of congregation analyzed has either remained the same or increased since 1998. However, when involvement in specific types of service-related activities are analyzed, divergent participation trends among congregations are observed. With regard to general involvement in political activities, the participation rates among evangelical Protestant, predominantly white, and politically conservative congregations have exhibited the most substantial decreases. Meanwhile, the political participation rates among Catholic, predominantly Hispanic, and politically liberal congregations have been increasing. These divergent trends are even more pronounced when involvement in specific types of political activities are analyzed.

Overall, congregations continue to play a substantial role in addressing social needs; yet, their involvement is shifting to occur primarily through acts of service and less through political engagement. This shift has important implications for congregations’ broader contribution to improving social conditions. Providing short-term relief of immediate needs through service provision without also pursuing long-term strategies to improve social conditions through political participation can limit congregations’ ability to effectively and comprehensively address social needs.

2. The Contemporary State of Congregation-Based Service Provision and Political Participation

Over the past three decades scholars have conducted extensive research on congregation-based service provision [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. These studies indicate that most congregations participate in some type of service-related activity, and the most common activities involve meeting people’s immediate needs for food, healthcare, clothing, and shelter. A small percentage of congregations have paid staff members who devote a portion of their work time to service provision; however, most congregations rely solely on volunteers to provide services [

9,

10]. Because the resource requirements associated with offering social services often exceed a congregation’s capacity, many congregations provide services in collaboration with other organizations [

7,

11,

12,

13]. A few congregations receive external funding to support their service provision and a very small percentage receive government funding [

1,

9]. As part of providing services, some congregations participate in activities such as assessing the needs of their community, promoting opportunities to provide volunteer service, and hosting representatives from social service agencies as guest speakers [

10,

14,

15,

16].

Additional research has examined how participation in service-related activities varies by congregations’ religious tradition, ethnoracial composition, and theological orientation [

3,

4,

17,

18,

19,

20]. Most of these studies indicate that evangelical Protestant congregations are the least likely to participate in service-related activities, while theologically liberal congregations are the most likely to participate. Further, these studies indicate that the ethnoracial composition of a congregation is not a significant predictor of service provision. Studies that focus on specific types of service-related activities reveal additional variations in participation rates across the aforementioned congregational subpopulations [

3,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25].

Similarly, scholars have conducted extensive research on congregation-based political participation. Although a smaller percentage of congregations participate in political activity than in service-related activity, the political participation rates are nonetheless sizable, and congregations are involved in a wide variety of political activities [

2,

10]. Some activities focus on helping members become politically informed, such as facilitating group discussions on political topics, distributing voter guides, and hosting political leaders [

26,

27]. Other activities focus on mobilizing members for political action, such as sponsoring voter registration drives, partnering with community organizing coalitions, lobbying political officials, and participating in demonstrations [

28,

29].

Research has also examined how participation in political activities varies by congregations’ religious tradition, ethnoracial composition, and political orientation [

23,

27,

30,

31]. Although participation in political activities occurs among all major types of congregations, most of these studies indicate that participation rates are highest among Catholic, predominantly black, and politically liberal congregations. Other studies that focus on specific types of political activities reveal additional variations in participation rates across the congregational subpopulations [

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38].

Collectively, these studies produce a detailed portrait of congregations’ participation in service-related and political activities, revealing how their participation rates vary for particular types of activities and the extent participation rates vary by congregations’ religious tradition, ethnoracial composition, and ideological orientation. Despite the trove of studies, however, research in this field is lacking a systematic national assessment of how congregations’ participation patterns in service-related and political activities have changed over time. To begin to fill this gap, this study analyzes data that span three decades to assess how congregation-based service provision and political participation have been changing since the 1990s. This study also examines how congregations’ involvement in specific types of activities has varied over this time period and whether the participation rates among major congregation types have varied as well.

4. Results

Table 1 displays the percentage of congregations involved in service-related and political activities in 1998, 2006–2007, and 2012

5. The table also indicates whether there has been a significant change in the percentage of congregations participating in each type of activity between 1998 and 2012. The analysis indicates that the percentage of congregations involved in at least one type of service-related activity has been increasing since 1998, and for each specific activity the percentage of participating congregations has either remained the same or increased since 1998. However, the percentage of congregations participating in at least one type of political activity has been decreasing, and for each specific activity the percentage of participating congregations has either remained the same or decreased since 1998. Although most of the changes in participation rates are modest, the divergent trends are widening the gap between the percentage of congregations involved in service provision and the percentage involved in political participation. Between 1998 and 2012, the percentage of congregations participating in at least one type of service-related activity increased from 71% to 78%, while the percentage of congregation participating in at least one type of political activity decreased from 43% to 35%.

The diverging participation patterns are even more pronounced when the participation rates for similar types of service-related and political activities are compared. In 2012, 57% of congregations had a group that assesses community needs, which is a 54% increase since 1998. In comparison, the percentage of congregations that had a group that discusses politics remained at approximately 6%. Similarly, in 2012, 31% of congregations hosted a representative from a social service agency as a visiting speaker, which is a 50% increase since 1998. Meanwhile, the percentage of congregations that hosted a political representative as a visiting speaker remained at approximately 9%. In 2012, more than 90% of congregations promoted opportunities to provide assistance to people outside their congregation. In comparison, only 15% of congregations promoted opportunities to participate in political activities, which is a 45% decrease since 1998. These divergent trends provide further evidence for congregations’ dampening interest in political participation contrasting with a growing interest in service provision.

As the percentage of congregations involved in service-related activities has been increasing, a few noteworthy shifts have also occurred with congregations’ funding sources for providing formal social services. In 2012, only 12% of congregations received external funding to support their social service programs, which is a 33% decrease since 1998. Furthermore, the percentage of congregations that receive government funding to support their programs has been decreasing. In 2012, less than 2% of all congregations that provided formal social services received government funding, which is a 65% decrease since 1998. At the same time, however, the median amount of money that congregations spend on social service programs has increased. In addition, the percentage of congregations with staff members who devote more than 25% of their work time to social service programs has nearly doubled since 1998. These trends indicate that even though a decreasing percentage of congregations have been relying on external funding to support their social services, the amount of money and resources congregations are allocating to social service provision has been increasing.

The second analysis examines subpopulations of congregations grouped by their religious tradition, ethnoracial composition, and ideological orientation, and it assesses differences in their participation patterns for specific types of service-related and political activities. This analysis helps to identify sources of the general upward trend in congregation-based service provision and general downward trend in political participation. It also identifies the types of congregations that diverge from the participation trends exhibited by the majority of congregations.

Table 2 displays the percentage of congregations by religious tradition, ethnoracial composition, and ideological orientation in 1998, 2006–2007, and 2012. The table also indicates whether there has been a significant change in the percentage of congregations within these subpopulations between 1998 and 2012.

The analysis indicates that between 1998 and 2012 the percentages of mainline Protestant and Catholic congregations have been decreasing and the percentage of black Protestant congregations has been increasing, while the percentage of evangelical Protestant congregations has remained at nearly 50%. During this same period, the percentage of predominantly white congregations decreased from 73% to 58% and the percentage of predominantly Hispanic congregations increased from 1% to 6%, while the percentage of predominantly black congregations remained at approximately 20%. The distribution of congregations based on their self-described theological orientation has remained relatively unchanged between 1998 and 2012. During this same period, the percentages of politically liberal and politically moderate congregations have been increasing; yet, over 50% of congregations continue to identify as politically conservative. Overall, the prevalence of evangelical Protestant and theologically conservative congregations has remained stable, while the prevalence of predominantly white and politically conservative congregations has been decreasing. Although assessing changes in the population of U.S. congregations is not the focus of this study, these changes have implications for the overall contribution of congregations to service provision and political participation.

Analyzing the service provision participation patterns among subpopulations of congregations reveals sources of the general upward trend and identifies the types of congregations that deviate from this trend.

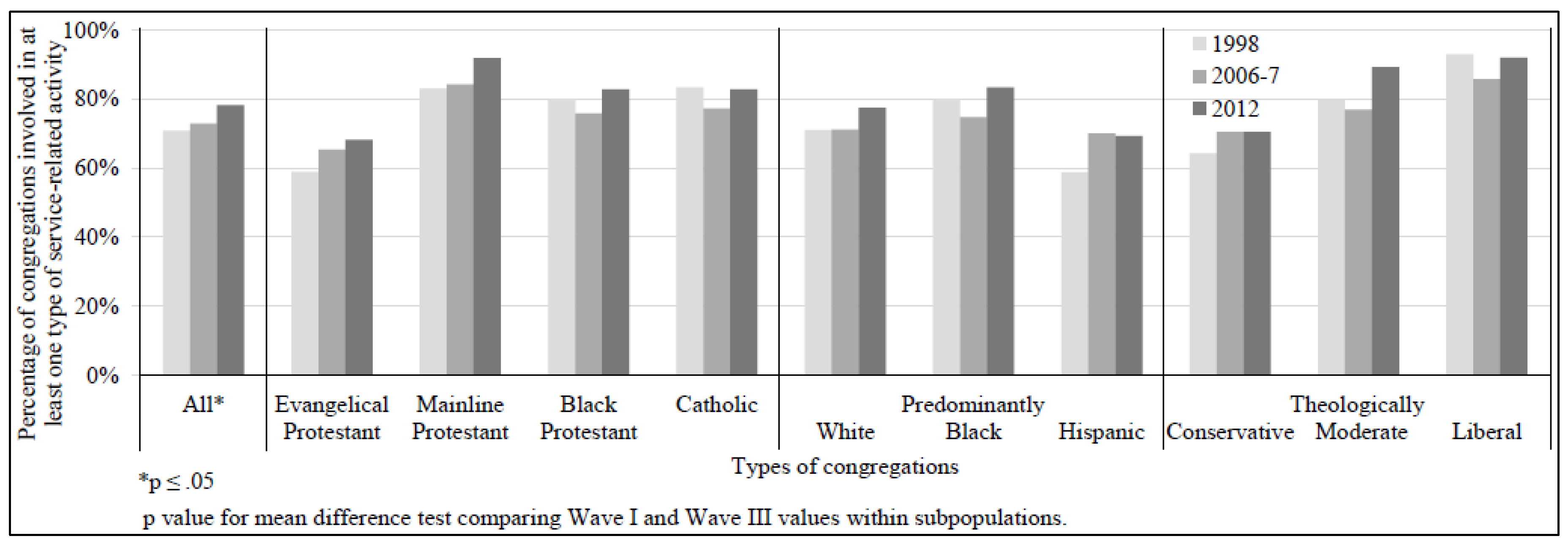

Figure 1 displays the percentage of congregations by subpopulation involved in at least one type of service-related activity in 1998, 2006–2007, and 2012. The figure illustrates that the service provision participation rate among every type of congregation analyzed has either remained the same or increased since 1998. This finding provides strong evidence that the substantial and increasing involvement in service-related activities among congregations is not isolated to a select few types of congregations; rather, participation is prevalent among most types of congregations.

Differences in service provision participation patterns among congregations become evident, however, when specific types of service-related activities are analyzed.

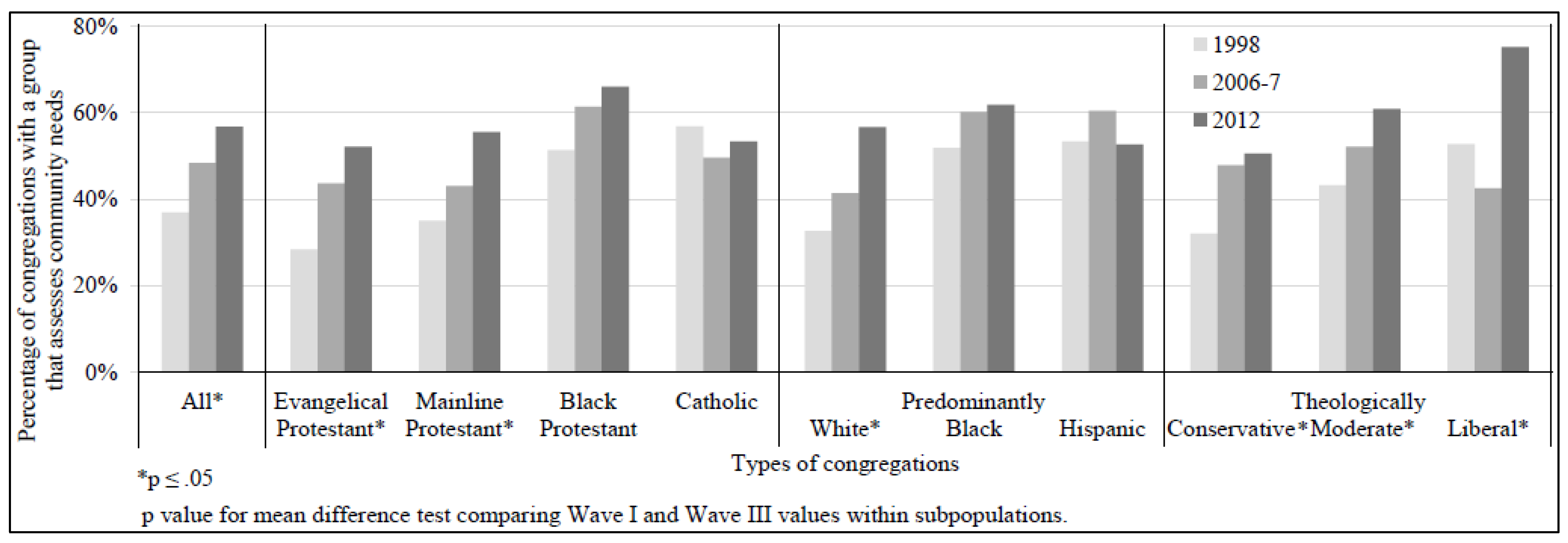

Figure 2 displays the percentage of congregations by subpopulation with a group that assesses the needs of its surrounding community. Between 1998 and 2012, the participation rate among Catholic congregations for this activity has remained steady at approximately 50%, while the rate among each major type of Protestant congregation has been increasing. Evangelical congregations had the largest increase (from 28% to 52%) and black Protestant congregations had the highest participation rate in 2012 (66%). In 1998, predominantly black and Hispanic congregations were significantly more likely than predominantly white congregations to have a group that assesses community needs; however, since then, the participation rate for this activity among predominantly white congregations has increased 73%—making their participation rate nearly equal to that of predominantly black and Hispanic congregations. A similarly substantial increase in needs-assessment participation occurred among theologically conservative congregations as well. These results indicate that much of the increase in community needs assessments derives from increasing participation rates among evangelical Protestant, predominantly white, and theologically conservative congregations, which represent the largest subpopulations of congregations and until recently, had the lowest participation rates. These upward trends are consistent with recent research that observes increasing levels of evangelical social engagement on a broad range of issues [

41].

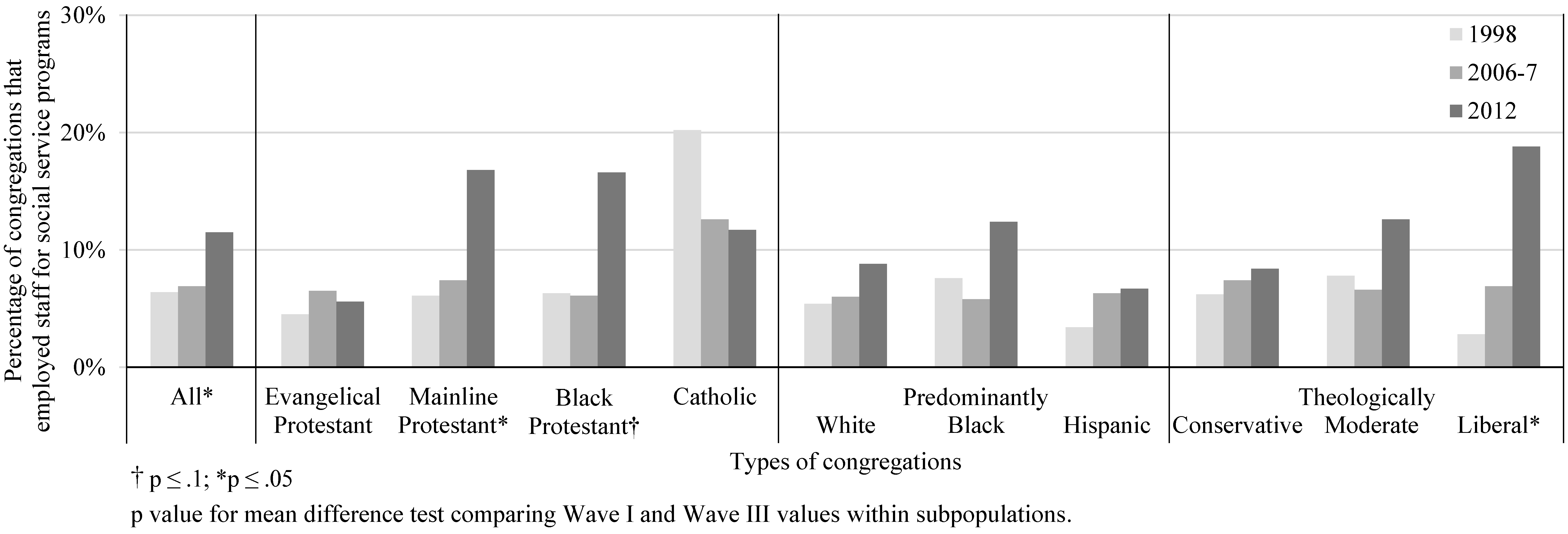

Figure 3 displays the percentage of congregations by subpopulation with staff members who devote at least 25% of their work time to social service programs. Between 1998 and 2012, the percentages of Catholic congregations with staff for social services has been decreasing, while the percentages among mainline Protestant and black Protestant congregations have more than doubled. During this same period, a modest upward trend in congregations employing staff for social services occurred among predominantly white and Hispanic congregations as well as among theologically conservative and liberal congregations. The largest increase occurred among theologically liberal congregations, whose participation increased more than six-fold from 3% to 19%. Although this study does not assess the depth of congregations’ involvement in service-related activities, this particular activity—allocating staff time to providing social services—certainly signals substantial involvement in service provision

6.

Analyzing the political activity participation patterns among subpopulations of congregations reveals sources of the general downward trend and identifies the types of congregations that deviate from this trend.

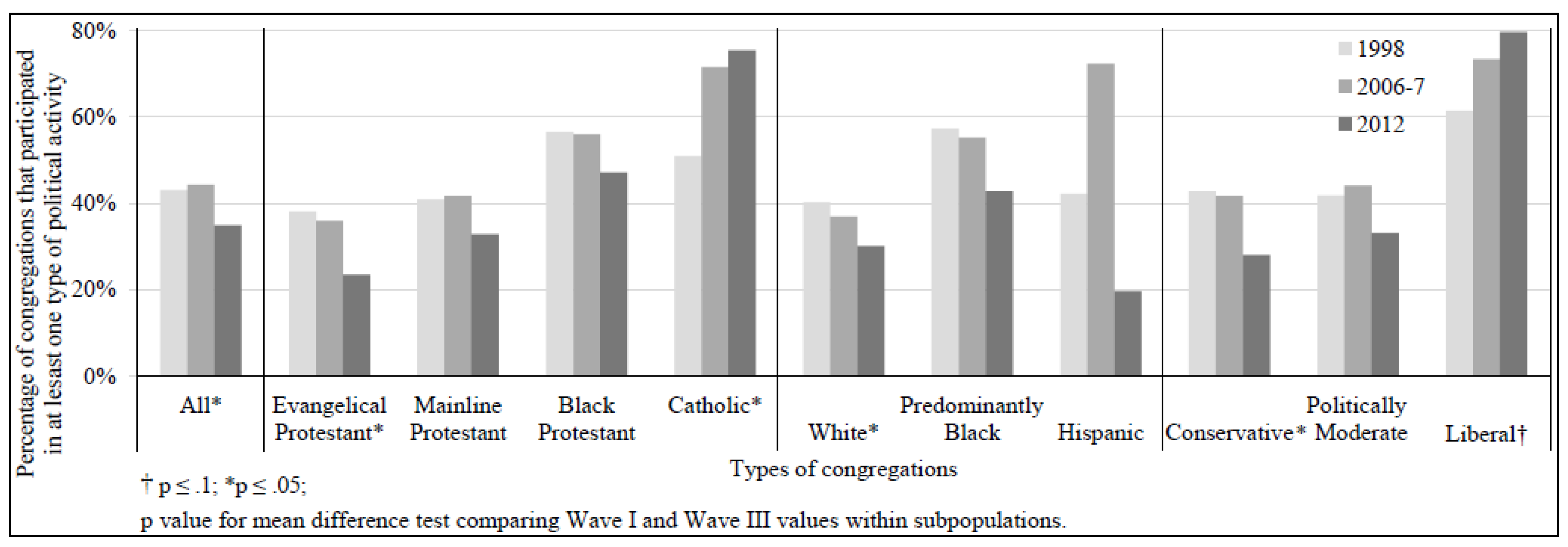

Figure 4 displays the percentage of congregations by subpopulation involved in at least one type of political activity in 1998, 2006–2007, and 2012. The figure illustrates that the political participation rate among each major type of Protestant congregation has been decreasing since 1998. The largest decrease occurred among evangelical congregations, whose participation dropped from 38% to 24%—the lowest participation rate among the religious traditions analyzed. During this same period, however, the participation rate among Catholic congregations has been increasing. By 2012, 75% of Catholic congregations were participating in at least one type of political activity. Additionally, the participation rate has been decreasing among politically conservative congregations and increasing among politically liberal congregations. In 1998, liberal congregations were 1.4 times more likely than conservative congregations to participate in political activities; since then, they have become 2.8 times more likely to participate. This analysis indicates that much of the decrease in congregation-based political activities derives from decreasing participation rates among evangelical Protestant, predominantly white, and politically conservative congregations. Offsetting this decrease are the political activities of Catholic and politically liberal congregations, whose participation rates have been substantial and increasing since 1998.

Differences in political participation patterns among congregations become more pronounced when specific types of political activities are analyzed.

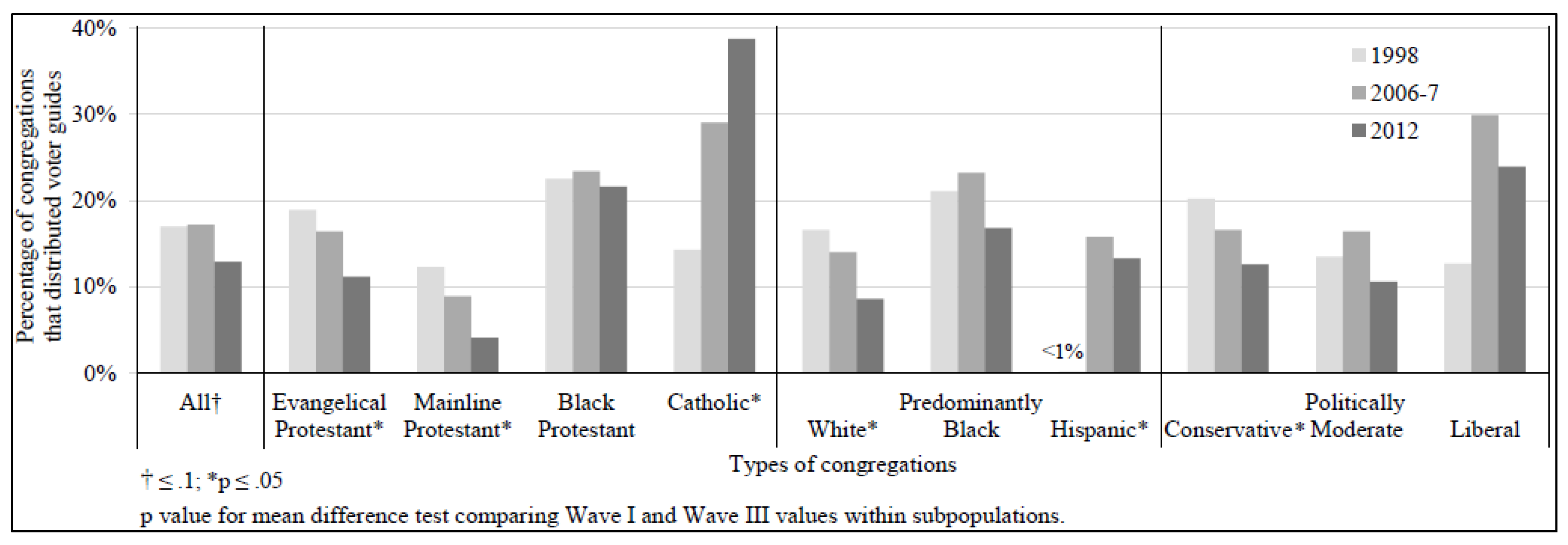

Figure 5 displays the percentage of congregations by subpopulation that distributed voter guides. In 1998, participation rates for this activity were highest among black Protestant and evangelical Protestant congregations (23% and 19% respectively); however, in 2012, the percentage of evangelical Protestant congregations that distributed voter guides decreased to 11%. Meanwhile, the percentage of Catholic congregations distributing voter guides has more than doubled since 1998—increasing from 14% to 39%—which surpasses the participation rate among each major type of Protestant congregation by a wide margin. Similar to the divergent trend among Catholic congregations is an increase in the participation rate among predominantly Hispanic congregations. Between 1998 and 2012, the percentage of predominantly Hispanic congregations distributing voter guides increased from less than 1% to 13%. During this same period, the percentage of predominantly white congregations distributing voter guides halved to 9% and the participation rate among black congregations remained steady at approximately 17%. Similar trends are observed among the other activities that focus on helping members become politically informed (results not displayed). The percentage of black Protestant congregations participating in these types of activities remained relatively unchanged, while the participation rates increased among Catholic and Hispanic congregations and decreased among evangelical and white congregations.

Similar trends are also observed for activities that focus on mobilizing members for political action.

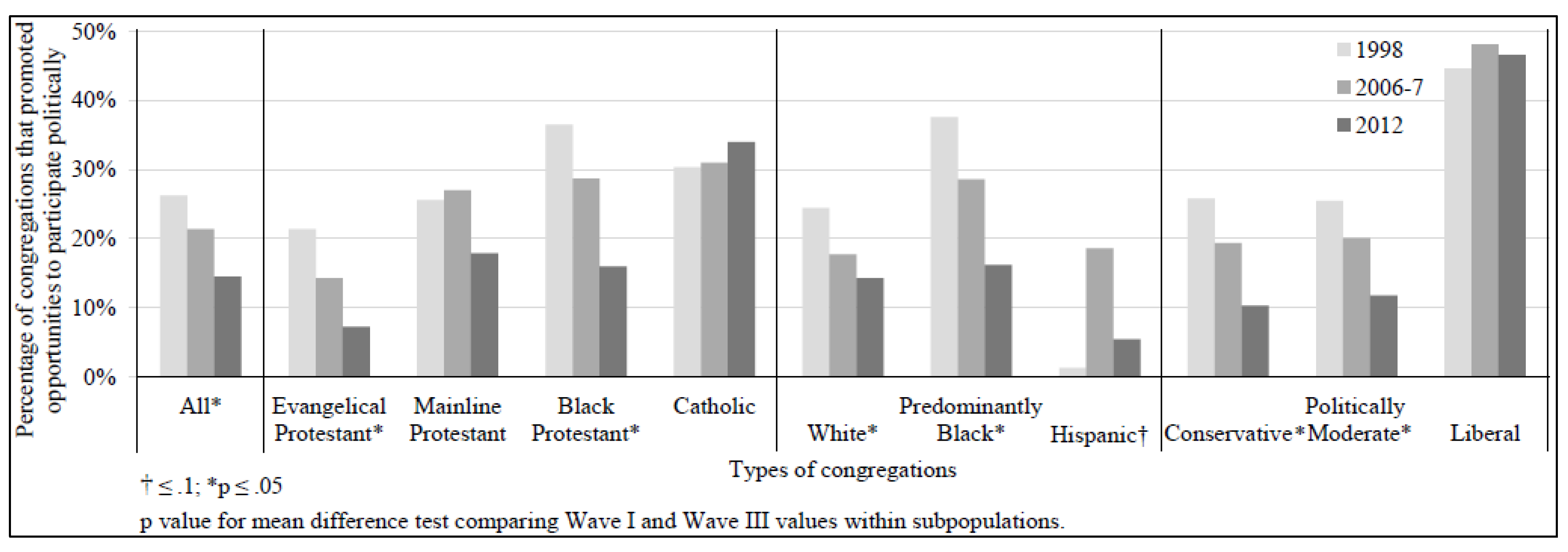

Figure 6 displays the percentage of congregations by subpopulation that promoted opportunities for their members to participate politically. Between 1998 and 2012, the participation rate among Catholic congregations for this activity remained at approximately 33%, while the rate among each major type of Protestant congregation has been decreasing. Black Protestant congregations had the largest decrease (from 36% to 16%) and evangelical congregations had the lowest participation rate in 2012 (7%). During this same period, the percentage of predominantly white and black congregations that promoted opportunities to participate politically decreased significantly, while the percentage of predominantly Hispanic congregations that promoted such opportunities increased marginally.

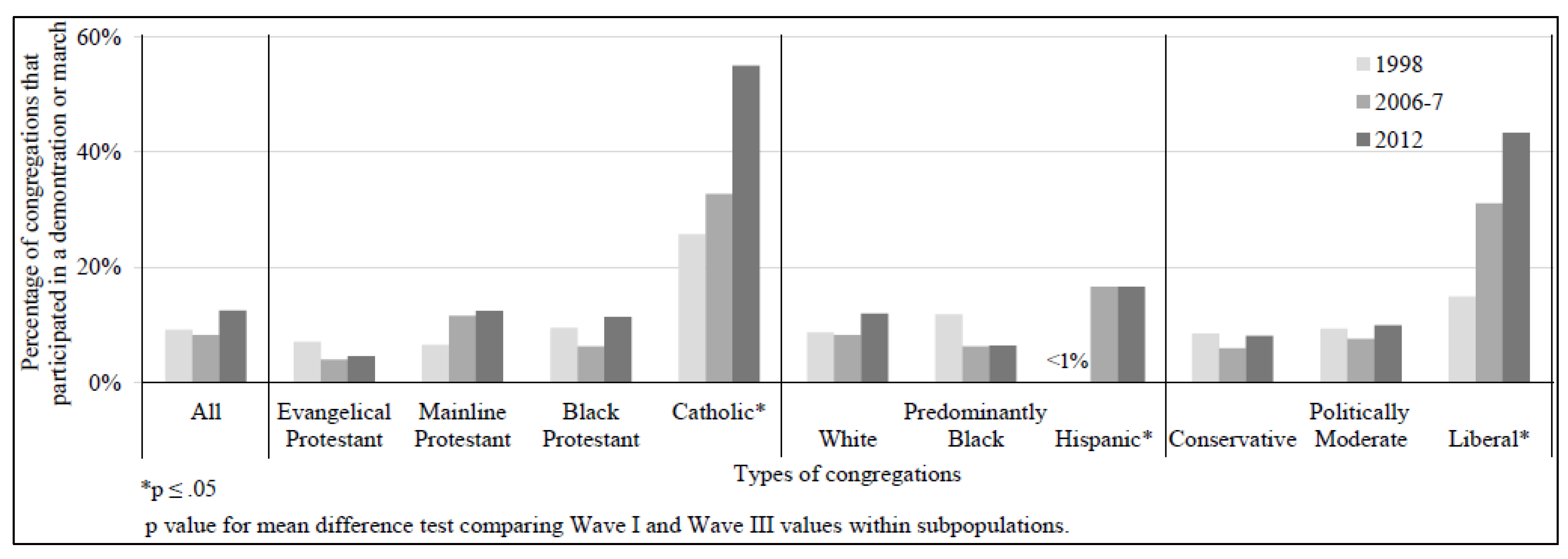

Figure 7 displays the percentage of congregations by subpopulation that participated in a demonstration or march. In 1998, Catholic congregations were at least two times more likely than each major type of Protestant congregations to participate in a demonstration or march. Since then, the percentage of Catholic congregations involved in this activity has more than doubled, while the participation rates among the Protestant congregations have remained the same. In 2012, more than half of all Catholic congregations had participated in a demonstration or march, which makes their participation rate for this activity four times greater than those observed among the Protestant congregations. Similarly, the percentage of Catholic congregations that had lobbied an elected official doubled between 1998 and 2012, increasing from 12% to 24%. Similar to the divergent trend among Catholic congregations is an increase in the participation rate among predominantly Hispanic congregations. Between 1998 and 2012, the percentage of predominantly Hispanic congregations that participated in a demonstration or march increased from less than 1% to 17%. Over this same period, the participation rate among predominantly white and black congregations remained at approximately 10%.

Divergent trends were also observed among congregations with different political orientations. For every political activity analyzed, the participation rates among politically conservative congregations have either remained the same or decreased since 1998, while the participation rates among politically liberal congregations have either remained the same or increased. Between 1998 and 2012, the percentage of politically conservative congregations that distributed voter guides decreased from 20% to 13%. Meanwhile, the percentage of politically liberal congregations that distributed voter guides increased marginally from 13% to 24%. Similarly, the percentage of politically conservative congregations that promoted opportunities to participate politically decreased from 26% to 10%, while the percentage of politically liberal congregations that promoted such opportunities remained steady at approximately 45%. During this same period, the percentage of politically conservative congregations that participated in a demonstration or march remained steady at approximately 8%, while the percentage of politically liberal congregations that participated in a demonstration or march almost tripled, increasing from 15% to 43%.

5. Discussion

Despite the few divergent trends, the substantial and generally increasing participation rates in service-related activities among most types of congregations supports the view that service provision is an institutionalized and nearly universal practice of congregations. Congregational political participation, however, appears to be becoming a niche practice. While many types of congregations exhibit less substantial and generally decreasing political participation rates, participation rates are relatively high among Catholic and politically liberal congregations and increasing substantially among predominantly Hispanic congregations. The following paragraphs discuss contours of the divergent trends in political participation exhibited among Catholic, politically liberal, and predominantly Hispanic congregations.

The high percentage of Catholic congregations involved in political activities is not a new finding; however, it is noteworthy that their participation rates have increased, while the rates among each major type of Protestant congregation have either remained the same or decreased. Furthermore, Beyerlein and Chaves [

27] observed that in 1998 the primary differences in congregations across religious traditions were not in the rates of participation, but rather in the types of political participation. Each religious tradition engaged in politics in distinct ways. While this observation remains true among the major types of Protestant congregations, substantial shifts have taken place such that the rate of participation has become a primary difference between Catholic congregations and Protestant congregations. By 2012, Catholic congregations had the highest participation rate for every political activity analyzed except for hosting a political representative as a visiting speaker.

The trend of fewer politically conservative congregations and more politically liberal congregations participating in political activities runs counter to popular perceptions [

42]. These perceptions are fueled by media outlets and political pundits, whose coverage of religion and politics tends to focus almost exclusively on the religious right and rarely even mentions religious progressives [

43]. Although the overall number of politically-engaged conservative congregations remains greater than the number of politically-engaged liberal congregations, the gap is shrinking and the difference in public attention each group’s political activity receives is of greater magnitude than the difference in their actual levels of engagement [

44]. The persistent perceived prominence of the religious right and relative absence of religious progressives in the political arena is partly attributable to three related factors. First, the general rightward shift of American political culture since the 1980s has resulted in the policy positions of religious progressives receiving less of a public hearing [

45]. Second, the religious right has mobilized so effectively for a media-oriented political culture that its representatives have crowded out religious voices advocating for progressive policies [

46]. Third, secular voices—sometimes simply non-religious voices and sometimes clearly anti-religious ones—increasingly dominate progressive policy discourse [

47].

Another complex element of the findings is the seemingly contradictory evidence that the percentage of predominantly Hispanic congregations participating in specific types of political activities has been increasing, while the overall percentage of Hispanic congregations participating in at least one type of political activity has been decreasing. Although

Figure 4 illustrates a substantial drop in the percentage of Hispanic congregations that participated in at least one type of political activity, this statistic can be misleading. Additional analyses indicate that the initially substantial and increasing participation rate among Hispanic congregations between 1998 and 2006–2007, and the subsequent major decrease in participation in 2012, were produced primarily by changes in the participation rate for one type of activity—helping people register to vote, which increased from 41% to 66% between 1998 and 2006–2007, and then dropped to 11% in 2012. These substantial swings in participation rates correspond to changes in voter registration laws that significantly impacted congregations’—especially Hispanic congregations’—ability to help people register to vote.

In particular, the 1993 National Voter Registration Act made it much easier for community-based organizations to conduct voter registration drives, and which in turn contributed to burgeoning voter registration rolls for the next 15 years [

48,

49]. However, following the 2008 elections, which had the highest turnout rate since 1960 and the largest turnout of Hispanic and black voters in U.S. history, several states began introducing and enacting more stringent election regulations [

50]. Particularly relevant was legislation that imposed burdensome requirements on organizations seeking to help people register to vote [

51]. The most restrictive measures were passed in Southern states that have substantial Hispanic populations [

50,

52]. These laws led several civic engagement organizations to discontinue their voter registration activities; many of which had focused on registering racial and ethnic minorities, since minority citizens disproportionately register through voter registration drives [

50,

51].

Analyzing data from Wave I and Wave II of the National Congregations Study indicates that a significant number of Hispanic congregations were among the organizations that began participating in voter registration activities during the 15 years following the 1993 National Voter Registration Act. Analyzing the Wave III data indicates that between 2006–2007 and 2012 the percentage of Hispanic congregations involved in voter registration activities decreased significantly

7. This finding suggests that the major drop in participation may have been at least partly in response to the stricter regulations following the 2008 elections.

The large percentage of Hispanic congregations involved in voter registration activities in 1998 and 2006–2007 account for a substantial portion of the Hispanic congregations participating in at least one type of political activity. Consequently, when a significant percentage of Hispanic congregations had discontinued this activity by 2012, it led to the assessment that the general involvement in political activity among Hispanic congregations had decreased since 1998. Additional analyses, however, indicate that the participation rates among Hispanic congregations for all of the other political activities analyzed have either remained the same or increased since 1998. Based on these analyses, a more accurate assessment is that apart from the aberrations caused by changes in voter registration laws that disproportionately affected Hispanic congregations, the participation rate among Hispanic congregations involved in political activities has increased since 1998.

6. Conclusions

Although this study provides a detailed analysis of congregations’ involvement in service provision and political participation over the past three decades, it has limitations. First, the analysis is based on a limited number of service-related and political activities; other participation patterns could be observed if a wider variety of activities were analyzed. In addition, the data on congregations’ involvement in these activities were collected with minimal probing, and studies have demonstrated that additional probing results in a larger percentage of congregations reporting involvement [

4,

10]. Furthermore, other methodological differences, such as using narrow or broad definitions of congregation-based service provision and political participation as well as giving respondents a list of activities to select from

versus asking them to recall activities from memory, can influence a congregation’s likelihood of reporting involvement in such activities and may have produced differences in the reported participation rates across studies [

4,

10]. In order to ensure that the longitudinal analyses in this study are unaffected by such methodological differences, this study relies on the three waves of data collected by the NCS, which used consistent methods across each of its three waves.

Second, this study does not analyze the extent of congregations’ involvement in service-related and political activities. Although it is important to understand differences between congregations with no involvement and those with at least some involvement, scholars and practitioners could benefit from understanding changes among congregations in the volume and scope of their service provision and political participation. In addition, with regard to congregation-based political activities, it would be beneficial to understand changes in the issues congregations are addressing as well as changes in the positions they are taking on those issues. Other studies have examined how the number, type, and content of activities congregations participate in have changed over time [

1,

2,

53], but these studies are limited to analyzing only two waves of data.

Third, this study does not examine how the size of a congregation is associated with its participation in service-related and political activities. Although the correlation between congregational size and participation in such activities is known to be significant and stable over time, one point is worth noting. Because this study conducted its analysis at the congregation level and did not differentiate between the size of congregations, this study underrepresents the percentage of church attenders in congregations that provide services and participate politically. Since it is also important to know the number of people exposed to congregation-based service-related and political activities, future studies could conduct similar change-over-time analyses at the attendee level.

Fourth, the analysis of participation patterns among congregational subpopulations does not include non-Christian congregations nor ethnoracially diverse congregations

8. The relatively small percentages of non-Christian congregations in the U.S., and subsequently in the NCS, inhibits analytical precision, and combining all of the congregations from non-Christian traditions into one category would obscure any differences that exist between those traditions. Future research could collect sufficiently large samples of congregations within these less prevalent traditions and conduct similar longitudinal analyses going forward. In contrast, the NCS does contain a sufficiently large number of ethnoracially diverse congregations; however, these congregations were not included in the analysis for important methodological reasons

9. Within the subset of ethnoracially diverse congregations, there is substantial variation in ethnoracial composition. Some have one ethnoracial group that represents a large majority of its members, others are split 50/50 across two ethnoracial groups, and some have equal representation across multiple ethnoracial groups. Thus, combining each type of ethnoracially diverse congregation into one category would make it difficult to specify the source of variation in outcomes. This limitation is not unique to congregational studies; it pertains to any study attempting to analyze outcomes associated with ethnoracial diversity. Rather than treating ethnoracially diverse groups as having similar composition, researchers could use more refined methods that capture the variation in composition that exists among ethnoracially diverse groups. Finally, future research could enhance understanding of congregational activities by analyzing how congregation-based service provision and political participation are associated with the interaction between a congregation’s religious tradition and ethnoracial composition.

Despite these limitations, this study fills a critical need by providing the first longitudinal analysis to assess how congregations’ involvement in service provision and political participation has changed over the past three decades. Overall, this study finds that among most types of congregations, the percentage participating in service-related activities is substantial and increasing, while the percentage participating in political activities is less substantial and decreasing. This decline in political participation has implications for congregations’ ability to effectively address social needs. Congregations can address social needs more comprehensively when they combine acts of service with political engagement. In doing so, they can relieve immediate needs while at the same time advocate for long-term solutions. Among the few types of congregations that have high and/or increasing participation rates in both service-related and political activities are Catholic, predominantly Hispanic, and politically liberal congregations. Although their representation among the total population of congregations in U.S. is relatively small, Catholic congregations are among the largest congregations and predominantly Hispanic and politically liberal congregations are among the fastest growing. While it is likely that a high percentage of congregations will remain involved in service provision, the future trajectory of congregation-based political participation remains uncertain.