The Effect of Prayer on Patients’ Health: Systematic Literature Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

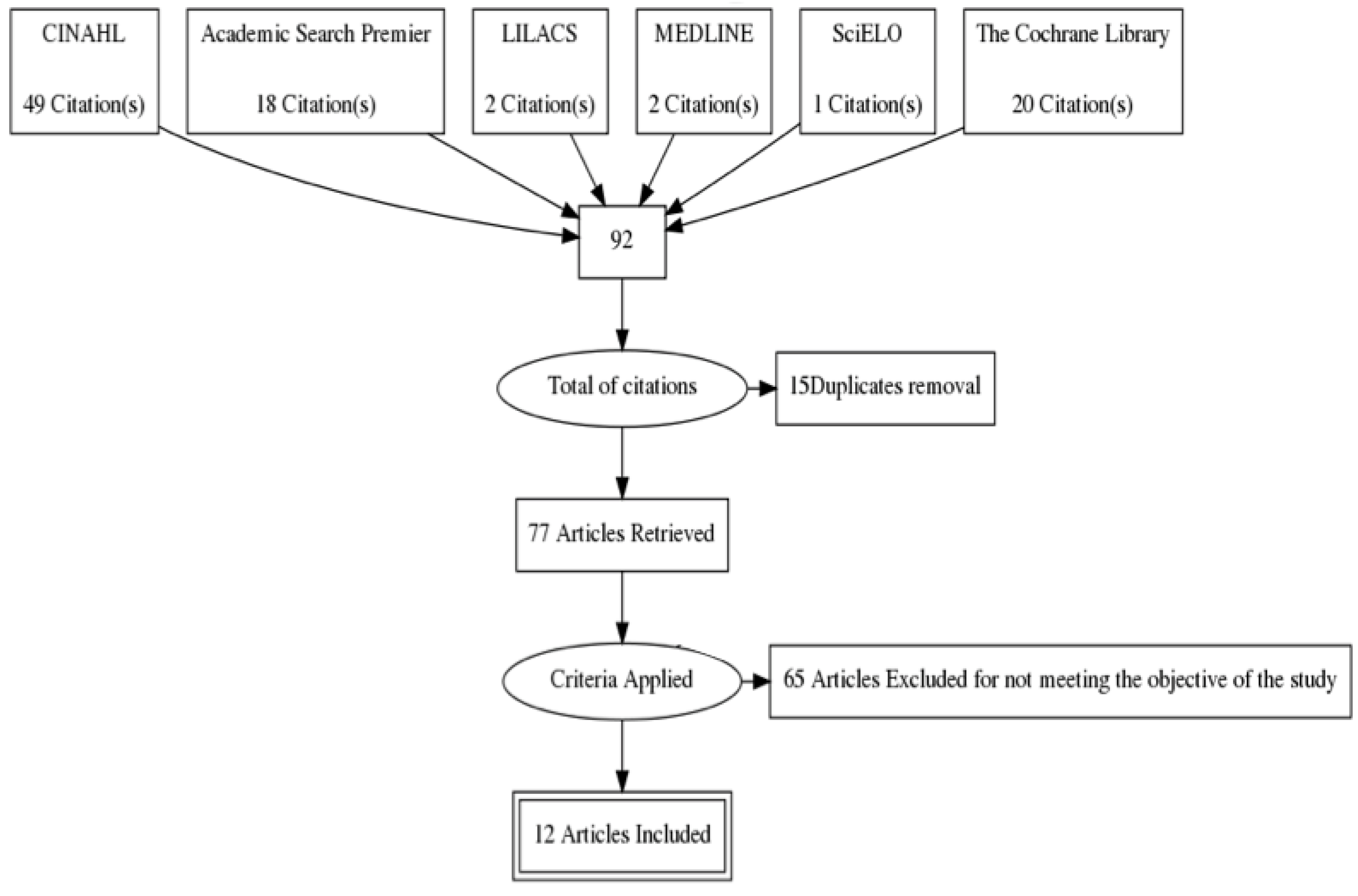

2. Method

3. Results

| Paper | Sample | Assessment (A)/Intervention (I) | Outcomes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paper 1 [22] | IG Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome patients: 40 Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome patients: 38 | CG Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome patients: 39 | (A) -Generic data (number of clinic visits, consultations and hospitalizations); -Mood (Profile of Mood States); -Quality of life (Functional Assessment of Human Immunodeficiency/Virus—FAIN version 4); -Illness severity; - CD4 + T lymphocyte count; -Triglycerides, cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL), alanine transaminase (ALT), aspartainine transaminase (AST), bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, indicators of toxicity antiretroviral therapy. (I) -Intercessory prayer was performed for one hour every day during 20 weeks. The intercessor imagined the patient and asked for them to be cured. -One IG with Intercessor Nurse Healers; -One IG with Intercessor Professional Healers. | -After 6 months there was a reduction in the absolute count of CD4 + lymphocyte in the IG (p = 0.02) compared to the CG; -After 12 months triglyceride levels had a reduction in GI compared to CG (−82.6 mg/dL vs. 8.6 mg/dL, p = 0.028). |

| Paper 2 [23] | Patients with depressive disorders and anxiety: 27 | Patients with depressive disorders and anxiety: 36 | (A) -Hamilton Rating Scales for Depression and Anxiety; -Life Orientation Test; -Daily Spiritual Experiences Scale; -Cortisol; (I) -Six weeks of prayer; -First intercessory prayer session lasted 90 minutes; and 60 minutes for the remaining sessions; -Intervention by a minister trained in healing prayer through Christian Healing Ministries. Based on the patient’s history the minister used a secular prayer (asking for pain relief and blessings); -The minister was often with the participant during the intervention. | -IG showed significant improvement in anxiety and depression, as well as more daily spiritual experiences and optimism compared to CG (p < 0.01); -Patients kept these results during one month after receiving the intervention (p < 0.01). |

| Paper 3 [24] | 371 Patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention or elective catheterisation 189 received prayer, music, image guidance and healing touch; 182 only received prayer. | 377 did not receive prayer; 185 had the music, image and touch intervention, and 192 received only regular care | (A) -Presence of adverse cardiovascular events readmission and/or death, at hospital discharge and six months afterwards; -Critical cardiovascular events such as a new myocardial infarction assessed by electrocardiogram or increased creatine phosphokinase. (I) -The 12 prayer groups involving Christians, Muslims, Jews and Buddhists were informed of the patients’ name, age and health condition. -Each group was responsible for the content, schedule and duration of prayers (ranging from 5 to 30 days). | -The unique use of prayer had no significant outcome on the clinical evolution of the groups, and the Odd Ratio was 0.97 (0.77–1.24) p = 0.8351, at confidence interval of 95%; -After six months, death and readmission was 0.93 (0.72–1.19) p = 0.5220, major cardiovascular event 0.85 (0.63 – 1.14) 0.2785 and death 1.13 (0.53 – 2.4) p = 0.7531. |

| Paper 4 [25] | Men and women aged 18-88 years who attended the Presbyterian Church: 45 | Men and women aged 18-88 years who attended the Presbyterian Church: 41 | (A) -Rating scales to assess prayers outcomes (1–4 and 1–5); -Medical Outcomes Study SF-20 (components: physical functioning, pain and mental health). -All data were collected before and after the intervention. (I) -12 intercessor volunteers, who received the patient’s first name and a written summary of their concerns and problems. They recorded how often and how long they prayed, and whether they were or not using a script about what was asked in prayer. Each group was asked to pray once a day for a month, targeting at least one or two participants. The average was twice a day and a duration of 3 minutes. | -Prayer decreases the level of concern of the participants who believe in a solution to their problem; -Prayer was related to better physical functioning (p < 0.002) for participants who believe in prayer. |

| Paper 5 [26] | Patients undergoing coronary artery bypass 601 were aware they were receiving the intervention 604 did not know if they were or were not receiving the intervention | Patients undergoing coronary artery bypass 597 did not know if they were or were not receiving the intervention | -Postoperative complication among 30 (Society of Thoracic Surgeons Adult Cardiac Surgery Database); -Any major event (defined by the New York State Cardiac Surgery Reporting System); -30-day mortality. (I) -Three groups (two Catholic and one Protestant) which had access to a list of patients; -The prayer was said at 0:00 pm the day before the surgery, and lasted for 14 consecutive days. | -52% of patients of IG who were not aware if they were receiving prayers (315/604) had complications compared to 51% (304/597) of patients of CG (relative risk 1.02, 95% CI 0.92–1.15); -59% of patients of IG who knew they were receiving prayer had complications (352/601) compared to patients of IG who did not know if they were receiving intercessory prayer (relative risk 1.14, 95% CI 1.02–1.28); -30-day mortality after surgery was similar for the three groups. |

| Paper 6 [27] | Patients admitted to the CCU: 484 | Patients admitted to the CCU: 529 | (A) -Collected information; -Comorbidities; -Length of stay in CCU; -Clinical outcomes. (I) - 15 teams with five intercessors who were given the participants’ first name; - Daily intercessory prayer over a four-week period. | -Patients of IG had lower weighted average when compared to CG (6.35 ± 7.13 vs. 0.26 ± 0.27; p = 0.04) and unweighted average (2.7 ± 0.1 vs. 3.0 ± 0.1; p = 0.04) considering the days patients were in Coronary Care Unit; -The length of stay in CCU was similar. |

| Paper 7 [28] | Patients with cardiovascular disease after hospital discharge: 400 | Patients with cardiovascular disease after hospital discharge: 349 | (A) -Death, heart failure, readmission or emergency department attendance, and coronary revascularization. -Three groups of patients were clustered according to risk: high risk (age = 70 years, diabetes mellitus, previous myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular disease or peripheral vascular disease), and low risk (no risk factors). (I) -Intercessory prayer was held once a week for 26 weeks; -215 intercessors were divided into five groups ranging from 1 to 65; -Intercessor groups prayed for 1-100 patients who were randomly distributed; -Intercessors were provided with the name, age, gender, diagnosis, and patients’ health status. | -There was at least one event in the IG and CG (25.6%) and the control group (29.3%) (odds ratio [OR], 0.83 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.60–1.14]; p = 0:25); -31.0% of patients of the IG had primary outcomes vs. 33.33% of CG (OR, 0.90 [95% CI, 0.60–1.34] p = 0.60); -The incidence of primary outcomes in low risk patients of IG was 17.0% vs. 24.1% in the CG (OR, 0.65 [95% CI, 0:20 to 1:36]; p = 0:12). |

| Paper 8 [29] | IVF Women: 88 | IVF Women: 81 | (A) -Pregnancy rate; -Implantation rate; -Number of babies. (I) -Intercessory prayer five days after treatment beginning and lasted for three weeks; -Each prayer group consisted of 3 to 13 intercessors that prayed for five patients asking for an increased pregnancy rate. | -IG had a higher pregnancy rate compared to CG (46.6% vs. 22.2%, p < 0.001); -IG had a higher implantation rate (16.3% vs. 8%, p = 0.0005) and multiple babies (17% vs. 4.9%, p = 0.0126). |

| Paper 9 [30] | Patients with bloodstream infection:1961 | Patients with bloodstream infection: 1702 | (A) -Number of deaths; -Length of stay in hospital from day one of a positive blood-culture; -Length of hyperthermia (temperature > 37.5 °C). (I) -Intercessors had a list with the first names of the patients of the IG. They asked for their well-being and full recovery. | -IG had lower number of deaths [28.1% (475/1691)] compared to the CG [30.2% (514/1702) (p = 0.4); -Regarding the length of stay in hospital and duration of fever, IG had significantly fewer events than the CG (p = 0.01 and p = 0.04, respectively). |

| Paper 10 [31] | Patients with rheumatic or psychological disease: 24 | Patients with rheumatic or psychological disease: 24 | (A) -Clinical State Scale; -Attitude State Scale; (Two times in consultation and after about 6 to 8 months). (I) -Six groups with 19 intercessors who were given participants’ first name; -Participation of all the 19 people involved in prayer, two as lone individuals and the rest were divided into 4 groups: -The group prayers were held once every two weeks, for one hour; -Individual prayer was conducted every day for 15 minutes; -Each patient received an average of 15 hours of prayer for a minimum period of 6 months. The prayer method used was silent meditation in which the intercessor focused all his attention on a short phrase that expresses some positive affirmation about God, which is most often obtained from the Bible. | Both instruments had similar results, but patients in IG had better results compared to the CG. |

| Paper 11 [32] | Pregnant women with gestational age of 37 weeks: 281 | Pregnant women with gestational age of 37 weeks: 285 | (A) -Type of delivery; -Apgar score; -Birth weight and macrossomy. -Age; -Gestational age; -Associated diseases; -Belief in God and religion. (All variables were dichotomized). (I) -The intercessors group was composed of six women, coordinated by a theologian. They asked for good delivery and health of the newborn, over nine consecutive days. | -Both IG and CG had a similar number of serious adverse events: spontaneous abortion (p = 0.53), intrauterine foetal death and (p = 0.30), low Apgar score (p = 0.34), preterm birth (p = 0.33), small size for gestational age (p = 0.62), macrossomy (p = 0.09), caesarean delivery (p = 0.68) and malformation (p = 0.99). |

| Paper 12 [33] | Mothers of children hospitalized with cancer: 30 | Mothers of children hospitalized with cancer: 30 | (A) -Inventory of Spielberger’s State Anxiety. (Data were collected at three times: before, after the intervention and 21 days after prayers had ended). (I) -The petition prayer was said three times a day for three weeks by the participants, who were instructed to go to the religious temple/space in the hospital to connect with God through prayer. | -After the intervention the difference between the anxiety averages in both groups was significant (p = 0.001); -IG had significant reduction in anxiety (CG: 58.93 ± 9.8 and IG: 40.96 ± 12.4). -No difference between the pre and post intervention groups (p = 0.001). |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IG | Intervention Group |

| IVF | In vitro Fertilisation |

| CG | Control Group |

| CCU | Coronary Care Unit |

| RCT | Randomized Clinical Trials |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- World Health Organization. WHOQOL and Spirituality, Religiousness and Personal Beliefs (SRPB). Geneva: World Health Organization, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Moacyr Scliar. “História do Conceito de saúde.” Revista Saúde Coletiva 17 (2007): 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramon Moraes Penha, and Maria Júlia Paes da Silva. “Meaning of spirituality for critical care nursing.” Texto Contexto Enfermagem 21 (2012): 260–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogério Rodrigues da Silva, and Deis Siqueira. “Spirituality, religion and work in the organizational context.” Psicologia em Estudo 14 (2009): 557–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilvete Soares Gomes, Marianne Farina, and Cristiano Dal Forno. “Espiritualidade, Religiosidade e Religião: Reflexão de Conceitos em Artigos Psicológicos.” Revista de Psicologia da IMED 6 (2014): 107–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heather S. L. Jim, James E. Pustejovsky, Crystal L. Park, Suzanne C. Danhauer, Allen C. Sherman, George Fitchett, Thomas V. Merluzzi, Alexis R. Munoz, Login George, Mallory A. Snyder, and et al. “Religion, Spirituality, and Physical Health in Cancer Patients: A Meta-Analysis.” Cancer 121 (2015): 3760–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raquel G. Panzini, and Denise R. Bandeira. “Spiritual/religious coping.” Revista Psiquiatria Clínica 34 (2007): 126–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- João P. Cabral. “A prece revisitada: Comemorando a obra inacabada de Marcel Mauss.” Religião e Sociedade 29 (2009): 13–28. [Google Scholar]

- Jaqueline Lopes, Mônica R. Lira, Gina A. Abdala, and Alberto M. S. Oliveira. “O impacto da reabilitação aquática associada à oração no desempenho funcional de pacientes pós-acidente vascular encefálico.” Saúde Coletiva 37 (2010): 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Silvia Caldeira. “Cuidado espiritual–rezar como intervenção de enfermagem.” CuidArteEnfermagem 3 (2009): 157–64. [Google Scholar]

- Mary Rute G. Esperandio, and Kevin L. Ladd. “I Heard the Voice. I Felt the Presence: Prayer, Health and Implications for Clinical Practice.” Religions 6 (2015): 670–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosta Carlos Eduardo. “Does prayer heal? ” Brasília Médica 34 (2004): 38–45. [Google Scholar]

- Kevin L. Ladd, and Bernard Spilka. “Prayer: A Review of the empirical literature.” In APA Handbook of Psychology, Religion, and Spirituality. Washington: American Psychological Association, 2013, vol. 1, pp. 293–307. [Google Scholar]

- Hélio P. Guimarães, and Álvaro Avezum. “O impacto da espiritualidade na saúde física.” Revista Psiquiatria Clínica 34 (2007): 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judith M. Wilkinson, and Karen van Leuven. “Fundamentos de Enfermagem: Teoria, Conceitos e Aplicações.” Avaiable online: http://www.livronauta.com.br/livro-Judith_M_Wilkinson_Karen_Van_Leuven-Fundamentos_de_Enfermagem_Teoria_Conceitos_e_Aplicacoes_2_Volumes-Roca-Sebo_Releituras_Portao-Curitiba-22954770 (accessed on 18 January 2016).

- Camila C. Carvalho, Erika C. L. Chaves, Denise H. Iunes, Talita P. Simão, Cristiane S. M. Grasselli, and Cristiane G. Braga. “The effectiveness of prayer in reducing anxiety in cancer patients.” Revista da Escola de Enfermagem da USP 48 (2014): 683–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leoni Zenevicz, Yukio Moriguchi, and Valéria S. Faganello Madureira. “The religiosity in the process of living getting old.” Revista da Escola de Enfermagem da USP 47 (2013): 433–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ian N. Olver, and Andrew Dutney. “A Randomized, Blinded Study of the Impact of Intercessory Prayer on Spiritual Well-being in Patients With Cancer.” Alternative Therapies 18 (2012): 18–27. [Google Scholar]

- David Evans. “Systematic reviews of nursing research.” Intensive and Critical Care Nursing 17 (2001): 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joanna Briggs Institute. Reviewers’ Manual. Adelaide: Joanna Briggs Institute, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cristina M. C. Santos, Cibele A. M. Pimenta, and Moacyr R. C. Nobre. “The pico strategy for the research question construction and evidence search.” Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem 15 (2007): 508–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alejandro R. Jadad, Andrew R. Moore, Dawn Carroll, Crispin Jenkinson, John D. Reynolds, David J. Gavaghan, and Henry J. McQuayj. “Assesing the Quality of Reports of randomized Clinical Trials: Is Blinding Necessary? ” Controlled Clinical Trials 17 (1996): 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John A. Astin, Jerome Stone, Donald I. Abrams, Dan H. Moore, Paul Couey, Raymond Buscemi, and Elisabeth Targ. “The efficacy of distant healing for human immunodeficiency virus—Results of a randomized trial.” Alternative Therapies 12 (2006): 36–42. [Google Scholar]

- Peter A. Boelens, Roy R. Reeves, William H. Replogle, and Harold G. Koenig. “A randomized trial of the effect of prayer on depression and anxiety.” The International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine 39 (2009): 377–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell W Krucoff, Suzanne W Crater, Dianne Gallup, James C Blankenship, Michael Cuffe, Mimi Guarneri, Richard A Krieger, Vib R Kshettry, Kenneth Morris, Mehmet Oz, and et al. “Music, imagery, touch, and prayer as adjuncts to interventional cardiac care: The Monitoring and Actualisation of Noetic Trainings (MANTRA) II randomised study.” Lancet 36 (2005): 211–17. [Google Scholar]

- Raymond F. Palmer, David Katerndahl, and Jayne Morgan-Kidd. “A Randomized Trial of the Effects of Remote Intercessory Prayer: Interactions with Personal Beliefs on Problem-Specific Outcomes and Functional Status.” The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine 10 (2004): 438–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herbert Benson, Jeffery A. Dusek, Jane B. Sherwood, Peter Lam, Charles F. Bethea, William Carpenter, Sidney Levitsky, Peter C. Hill, Donald W. Clem Jr., Manoj K. Jain, and et al. “Study of the Therapeutic Effects of Intercessory Prayer (STEP) in cardiac bypass patients: A multicenter randomized trial of uncertainty and certainty of receiving intercessory prayer.” American Heart Journal 151 (2006): 934–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- William S. Harris, Manohar Gowda, Jerry W. Kolb, Christopher P. Strychacz, James L. Vacek, Philip G. Jones, Alan Forker, James H. O’Keefe, and Ben D. McCallister. “A randomized controlled trial of the effects of remote intercessory prayer on outcomes in patients admitted to the coronary care unit.” Archives International Medicine 159 (1999): 2273–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennifer M. Aviles, Ellen Whelan, Debra A. Hernke, Brent A. Williams, Kathleen E. Kenny, Michael O’ Fallon, and Stephen L. Kopecky. “Intercessory prayer and cardiovascular disease progression in a coronary care unit population: A randomized controlled trial.” Mayo Clinic Proceedings 76 (2001): 1192–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwang Y. Cha, Daniel P. Wirth, and Rogerio A. Lobo. “Does Prayer Influence the Success of in Vitro Fertilization–Embryo Transfer? Report of a Masked, Randomized Trial.” Journal of Reproductive Medicine 46 (2001): 781–87. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Leonard Leibovici. “Effects of remote, retroactive intercessory prayer on outcomes in patients with bloodstream infection: Randomised controlled trial.” British Medical Journal 323 (2001): 1450–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- C. R. Joyce, and R. M. Welldon. “The objective efficacy of prayer: A double-blind clinical trial.” Journal of Chronic Diseases 18 (1965): 367–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maria I. Rosa, Fabio R. Silva, Bruno R. Silva, Luciana C. Costa, Angela M. Bergamo, Napoleão C. Silva, Lidia R. F. Medeiros, Iara D. E. Battisti, and Rafael Azevedo. “A randomized clinical trial on the effects of remote intercessory prayer in the adverse outcomes of pregnancies.” Ciência & Saúde Coletiva 18 (2013): 2379–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K. H. Dehghani, A. Zare Rahimabadi, Z. Pourmovahed, H. Dehghani, A. Zarezadeh, and Z. Namjou. “The Effect of Prayer on Level of Anxiety in Mothers of Children with Cancer.” Iranian Journal of Pediatric Hematology Oncology 12 (2012): 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- John M. Salsman George Fitchett, Thomas V. Merluzzi, Allen C. Sherman, and Crystal L. Park. “Religion, spirituality, and health outcomes in cancer: A case for a metaanalytic investigation.” Cancer 121 (2015): 3754–59. [Google Scholar]

- John A. Astin, Elaine Harkness, and Edzar Ernst. “The efficacy of distant healing: A systematic review of randomized trials.” Annals of Internal Medicine 6 (2000): 903–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David Brain Wolf. “Effects of the Hare Krsna Maha Mantra on Stress, Depression and the Three Gunas.” Ph.D. Thesis, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kuciano Bernardi, Peter Sleight, Gabriele Bandinelli, Simone Cencetti, Lamberto Fattorini, Johanna Wdowczyc-Szulc, and Afonso Lagi. “Effect of rosary prayer and yoga mantras on autonomic cardiovascular rhythms: Comparative study.” BMJ 323 (2001): 1446–49. [Google Scholar]

- Suzette Brémault-Phillips, Joanne Olson, Pamela Brett-MacLean, Doreen Oneschuk, Shane Sinclair, Ralph Magnus, Jeanne Wei, Marjan Abbasi, Jasneet Parmar, and Christina M. Puchalski. “Integrating Spirituality as a Key Component of Patient Care.” Religions 6 (2015): 476–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maria Inês Rosa, Fábio R. Silva, and Napoleão C. Silva. “A oração intercessória no alívio de doenças.” Arquivos Catarinenses de Medicina 36 (2007): 103–8. [Google Scholar]

- Teresa C. Camargo. “The role of the nurse participation in clinical trials: A review of the literature.” Revista Brasileira de Cancerologia 48 (2002): 569–76. [Google Scholar]

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Simão, T.P.; Caldeira, S.; De Carvalho, E.C. The Effect of Prayer on Patients’ Health: Systematic Literature Review. Religions 2016, 7, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel7010011

Simão TP, Caldeira S, De Carvalho EC. The Effect of Prayer on Patients’ Health: Systematic Literature Review. Religions. 2016; 7(1):11. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel7010011

Chicago/Turabian StyleSimão, Talita Prado, Sílvia Caldeira, and Emilia Campos De Carvalho. 2016. "The Effect of Prayer on Patients’ Health: Systematic Literature Review" Religions 7, no. 1: 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel7010011

APA StyleSimão, T. P., Caldeira, S., & De Carvalho, E. C. (2016). The Effect of Prayer on Patients’ Health: Systematic Literature Review. Religions, 7(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel7010011