There are good reasons, when comparing the United States with other nations, to expect that religion will have little to no influence on American politics. However, when looking within the United States there seems to be a lot of evidence to the contrary. Is there something wrong with our theories about religious influence or are we exaggerating the evidence because it is not comparative? Perhaps a little of both is occurring depending on the political and theoretical bias of the observer. In general, American conservatives tend to feel that religion is embattled in contemporary American culture while liberals tend to feel that Evangelical Protestantism, specifically, has overtaken the political right. Similarly, social scientists are divided on the extent to which religion matters to American politics.

First and foremost, the claim that God has been expelled from America’s public square, as made by Newt Gingrich and many other conservative pundits, is outlandish from a global comparative perspective. In fact, it seems that even conservatives who decry the left’s attempts to destroy religion will simultaneously boast that the United States is one of the most religiously tolerant nations on earth. This boast is supported by some facts. The United States consistently ranks at the top of the most religiously tolerant nations according to the three most accepted measures of religious freedom (see The Association for Religion Data Archives.

Yet it remains an empirical question of how important religion is to politics within a culture of religious tolerance and freedom.

1. Why Religion Should Not Matter

Religious diversity and state funding of religion are both expected to determine the political influence of religion within a society. The level of state religious favoritism (in tandem with state regulation of minority religions) is the most direct indicator that state and church institutions cooperate and have shared interests. Anthony Gill offers an intricate theory of how these relationships develop and demonstrates that religion most directly influences politics in nations with historically dominant religious traditions [

1,

2]. In these contexts, we expect and have evidence to show that religious authorities provide elites with political legitimacy, in the form of religious-ideological support, in return for religious favoritism.

While many post-industrial countries still bolster “state religions” with tax dollars and the suppression of religious competitors, the United States reports some of the lowest levels of religious favoritism and religious regulation in the world. This suggests that no single church or denomination monopolizes the attention of political elites or holds exclusive access to the halls of power. The United States also has a legal separation of church and state which secures an institutional “differentiation” of religious and political organizations.

In addition, there are reasons to think that religious differences within the United States are less important that in other countries. Robert Wuthnow, among others, has argued that denominational divisions have lost their edge over the past 50 years [

3,

4]. Additionally, while many conservative religious groups successfully fight against a growing tendency towards ecumenicalism, an overarching culture of religious tolerance pervades the American landscape. The election of Roman Catholic John F. Kennedy provided evidence that Protestant discrimination against Catholics had dropped to low levels by 1960. The fact that Presidential candidate Mitt Romney won the Republican primaries in 2012 suggests that many American Christians may also be willing to elect a Mormon President, again supporting the idea that nominal Christian identity stifles denominational conflicts.

Instead of inter-religious conflict, public debates about religion tend to be framed in terms of the secular versus the religious. While disagreements over perceived levels of secularization have motivated citizens to debate public policy on such issues as prayer in schools or the display of religious symbols in public spaces, American churches tend not to attack one another. And this lack of religious tension suggests that political elites have no leverage in pitting religions traditions and denominations against one another.

In addition, researchers who study the activities of individual churches and denominations in the United States agree that is it rare for a pastor or minister to openly support a political candidate or make political demands of his or her congregants [

5,

6]. As a whole, this research suggests that it is actually liberal and African-American churches which most openly, although also rarely, make politically-charged appeals. These findings go against the popular perception of White Evangelical churches as GOP recruitment centers.

In sum, the religious culture of the United States appears relatively tolerant, peaceful, inclusive, and politically neutral within a global comparative perspective. These positive characteristics suggest that the American political system is unimpeded by religious demands from dominant churches and clergy. In addition, the declining significance of denominationalism along with the largely apolitical activities of individual churches suggests that American religious diversity will not inspire inter-religious conflict anytime soon. Olson and Carroll summarize a common belief in the literature that “religion will not soon become a major axis of political conflict in America” and others have warned that the United States is not divided into clear “religious camps” with competing national agendas ([

7];[

8], p. 765). So why do we tend to think of American politics as dominated by concerns of faith?

2. How Religion Matters

Most obviously, American political candidates make a big deal of their “commitment to faith.” In a systematic analysis of national political speeches, Domke and Coe find that religious rhetoric has steadily been on the rise among both Republicans and Democrats since the Nixon administration [

9]. The religious language of our political leaders is so pervasive that it can inspire alarm when it is absent. Barrack Obama and Mitt Romney both had to address the concerns over their religiosity head-on; in both cases, they attempted to quell fears of their supposed religious deviance by maintaining that they are faithful Christians.

Religious social movements, usually trans-denominational in nature, have long attempted to influence public policy in the United States from both the left and right. Liberal and conservative activists sometimes employ a religious framing of social issues, most effective cases being the use of African American churches as the moral and institutional basis for the civil rights movement and, more recently, the various Catholic and Evangelical Protestant organizations which spearhead the pro-life movement [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14].

In fact, religious issues are often at the forefront of national political campaigns. The courting of the “religious vote” is an often discussed strategy among pundits and the media, and pollsters can neatly predict conservative voting behavior based on religious participation and self-identity. While there is some evidence from Manza and Brooks that Evangelical Protestants have not become more conservative, most research confirms this perceived trend towards a “religious right” and the electoral success of George W. Bush among Evangelical Protestants is unquestionable [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. Lydia Bean is researching the dynamics which have allowed the Republican Party to more successfully mobilize religious Americans [

20]. Her research demonstrates that while conservative clergy are not more politically active, key members of their congregations tend to be and utilize the church space to informally spread support for the GOP. Bean argues that there are no equivalent Democratic Party activists within liberal churches.

Still, there is active debate among academics concerning the significance and reality of the James Hunter’s “culture wars thesis”—the idea that American politics has shifted from class-based struggles to focus more on religious-cultural issues, such as abortion, gay marriage, and stem-cell research. Critics of this thesis analyze public opinion to demonstrate that Americans cannot be easily bifurcated into the social-cultural categories suggested by the thesis [

10,

11,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. Nevertheless, Hunter’s ideas regarding the importance of conceptions of moral authority are useful. For instance, Davis and Robinson utilize survey data concerning God’s moral authority to distinguish between “religious traditionalists” and “religious modernists” and find that modernists are more likely to view individuals as personally responsible for their destinies [

21]. Wayne Baker also explains value differences within the American population with reference to basic variation in beliefs about moral authority [

28]. This research suggests that religious concerns are preeminent in many voters’ minds and are often the lens through which they understand policy proposals and debates.

In addition, Michael Lindsay demonstrates how Evangelical identity, in particular, has risen to become a useful resource in influential social networks [

29]. Lindsay argues that Evangelical networks foster collaboration and proliferate throughout major institutions of power in the United States, namely on Wall Street, on Capitol Hill, in Hollywood, and halls of higher education. While these networks may not be focused on any religious agendas

per se, they serve as a kind of “old boys club” in which fellow Evangelicals trust and hire one another to greater degree.

All of this research highlights two major findings. First, religion is a powerful force and salient political issue in American society. Second, the ways in which religion impacts politics in the United States is unique when considered within a comparative framework. It is not through the direct influence of religious leaders and churches on public officials but rather through religious framing of issues by politic elites and through embedded networks of Evangelicals in our major institutions that religion flexes its political muscle. Jonathan Fox notes this clear distinction between the legal

versus the ideological authority of religion in the United States, which Daniel Philpott explained as the result of high levels of religious-political “differentiation” combined with widespread belief in “political theology” [

30,

31]. In sum, the legal and institutional differentiation of religious and political spheres (the separation of church and state) has not diminished the power of religious political rhetoric in the United States as it has elsewhere in the world.

As Philip Converse alerted political researchers in the 1960s, “there is fair reason to believe that [religious differences] are fully as important, if not more important, in shaping mass political behavior than are class differences” ([

32], p. 248). In order to better understand the uniqueness of this relationship we must delve into how the United States is ultimately a religious exception to many worldwide trends, in particular, the continuing popularity of American political theology.

3. American Religious Exceptionalism

The United States is clearly a religious exception in the post-industrial world. Americans attend church more than Western Europeans, they have more religiously conservative sexual and social attitudes, and they link their theology to free market economics more directly [

33,

34]. Emerson and Smith describe American Protestantism as synonymous with economic individualism [

15,

35]. Smith explains:

“American individualism…prescribes that individuals should not be coerced by social institutions, especially by the government, and particularly not on personal matters; that freedom to pursue individual happiness is a paramount good; that people shouldn’t meddle too deeply in other people’s business; and that the government usually provides poor solutions to social and cultural problems” ([

36], p. 211).

Davis and Robinson find the opposite relationship in 21 European countries and Israel [

37]. They discover that “what theologically distinguishes modernists (including believers and secularists) from the religiously orthodox is their greater individualism” ([

37], p. 1632). In this way, religious Americans look very different from their religious counterparts in other post-industrial nations. Quite simply, religious Americans are more conservative morally, sexually, and economically.

Possibly the most telling difference is in how some religious Americans understand the separation of church and state. While nearly all Americans advocate this separation, a strong minority feel that that the United States is a “Christian nation” and that the government should actively promote “Christian morals.” However, this is not just another measure of religiosity. American Christians who are very religious according to such indicators as worship attendance, prayer, religious donations and volunteerism, are not uniform in their sense how they understand the relationship between their religion and politics.

Distinct from the concept of religiosity is an American’s belief in “sacralization ideology”, a tongue twisting yet important concept. Stark and Finke explain that sacralization ideology means that “there is little differentiation between religious and secular institutions and that the primary aspects of life, from family to politics, are suffused with religious symbols, rhetoric, and ritual.” ([

38], p. 284). Sacralization ideology is the extent to which individuals feel that their religion should influence and be a part of public policy debates; Philpott calls this

political theology, “the set of ideas that religious actors hold about political author and justice” ([

31], p. 505). In many pre-industrial countries sacralization ideology or political theology appears very popular or at least is unquestioned in that it exhibits itself in Peter Berger’s concept of a “sacred canopy”. For Berger the pre-modern world is often imbued with religious traditions that are so “taken-for-granted” that they are woven in the fabric of social life [

39].

The importance of sacralization ideology is most pronounced in the Muslim world, where Islamic theology asserts that political discussion should be guided to greater or lesser extent by Shariah Law. Conservative Muslims express sacralization ideology when arguing that all aspects of personal, social and political life should be governed by religious rules and regulations. However, there are diverse opinions regarding these matters within Muslim communities and these differences may underlie fundamental political and social divisions within Islam.

Modernization tends to bring with it a separation of religious and secular spheres and, in turn, the decline or disappearance of sacralization ideology. The separation of church and state in the United States is the primary example of how these spheres are conceptually and legally divided in the modern world. However, many Americans appear similar to pre-modern individuals in their attachment to sacralization ideology, or the common American notion that political decision-making requires consideration of “the sacred”—or in the case of American Christianity—God.

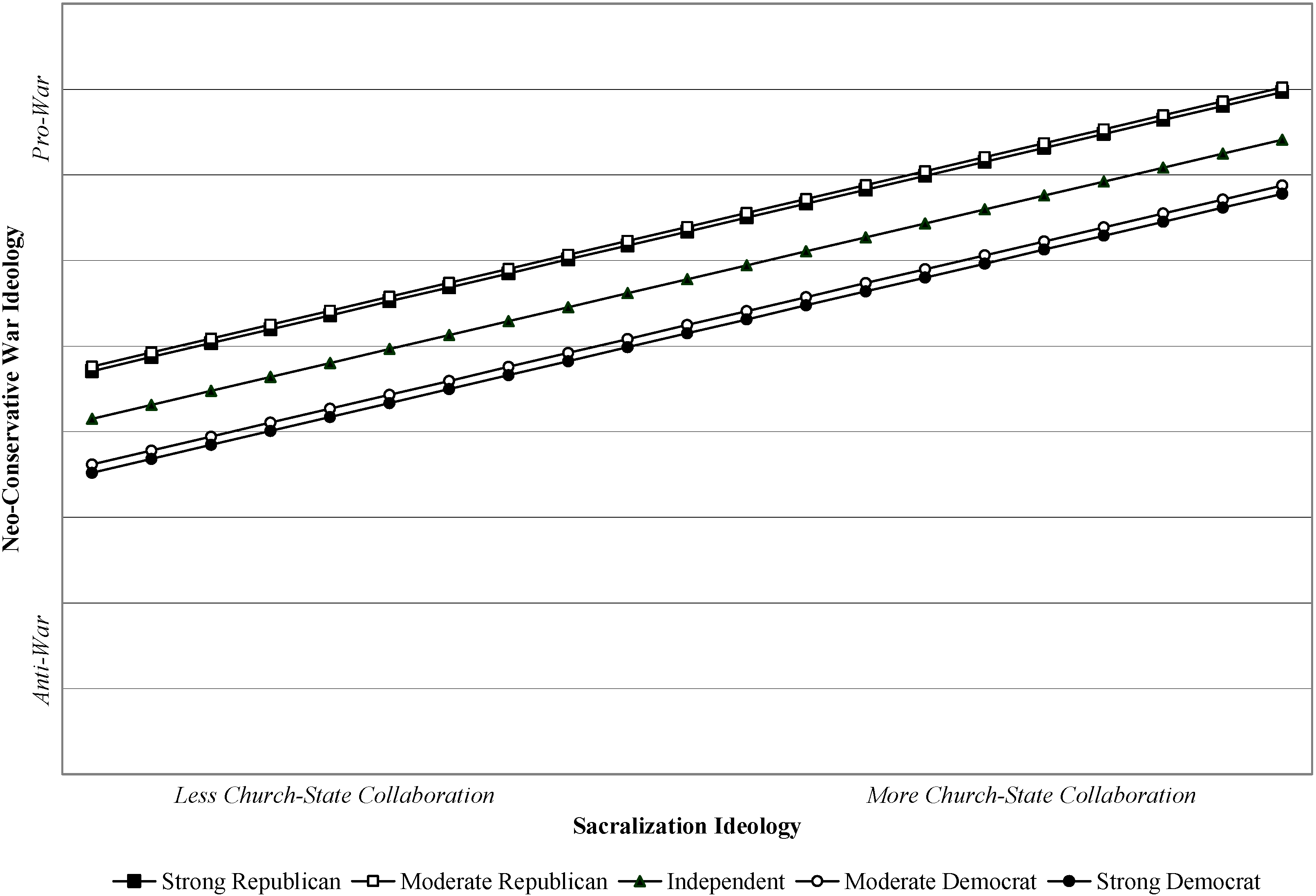

Carson Mencken and I found that sacralization ideology was the best predictor of whether an American thought that the Iraq War was justified [

40]. In this instance, beliefs about the religious purpose of the Iraq War proved more important than political affiliations, identities, and Social Economic Status in determining whether an American supported the war effort.

Figure 1 replicates part of this analysis and depicts the surprising strength of sacralization ideology. Of great interest is the fact that a “strong Democrat” was more likely to support the Iraq War than a “strong Republican” if he or she thought that religion

should be part of the reason we went to war.

Figure 1.

Predicted probabilities of pro-war attitudes (by sacralization ideology and political affiliation).

Figure 1.

Predicted probabilities of pro-war attitudes (by sacralization ideology and political affiliation).

Source: Baylor Religion Survey [

23].

Why did sacralization ideology predict opinions about the Iraq War so well? Most clearly, President Bush framed the war effort in religious terms, often referring to a historic fight of good against evil [

40].

In sum, Americans are simply more religious than most other citizens of post-industrial nations and are more likely to believe that religion

should influence politics—the essence of sacralization ideology. Whether this kind of ideology is on the rise is unknown but past generations of conservative Christians were some of the least politically active Americans. This all changed in recent decades with more and more Protestant Evangelicals resisting the “individual-level privatization” of their faith in the public sphere [

41]. Consequently, the rise of conservative religious politics does not necessarily reflect a rise in conservative religionists (they have always existed), but a change in their attitudes about the role of religion in politics.

To better explore this phenomenon and its importance in a comparative framework, we need to better understand the role of beliefs about God around the world and their relationship to politics. Images of God reveal something deep about the worldview of believers and provide a unique window into understanding how and when religion can be used politically [

42].

4. God around the World

A universal trait of politics around the world is its reliance on symbols to communicate complex messages and principles to the masses. This ongoing process of building political legitimacy and framing moral debates along policy dimensions relies on and draws from cultural and national traditions. In the world, there is no symbol or tradition more common than God.

If we treat the word “God” as a metaphor than we must know to what it is referring. Clearly, God means something different across religious traditions and denominational groupings, and between individuals. Our task is then to somehow measure this theological diversity to see if it is meaningful in some larger social or political sense.

Max Weber famously provides us with a four-fold typology of world religions—(i) other-worldly asceticism; (ii) inner-worldly asceticism; (iii) other-worldly mysticism; and (iv) inner worldly mysticism [

43]. Of these, inner-worldly asceticism, Calvinism being an exemplar, is the religious ideology which best motivates social change because it links salvation directly to earthly ethical duties. While this is a helpful insight, Collins laments that Weber’s typology “is still overgeneralized, since it includes not only economic self-discipline leading to rationalized capitalistic development, but also military crusades; among the latter we find Christian, as well as Muslim holy wars, Cromwell’s armies, and, since Weber’s day, modern instances including militant political mobilization among both Christian fundamentalists and the activist Christian left” ([

44], p. 172). Collins’ point is well taken and indicates an area in which we might be able to improve.

Rodney Stark’s work builds on Weber’s insights by more specifically analyzing how various forms of inner-worldly asceticism motivate believers. In general, this type of theology is monotheistic, which for Stark, makes all the difference. Specifically, Stark asserts that “the extent to which religion enters into either solidarity or conflicts appears to be in direct proportion to the scope of the Gods involved” ([

45], p. 33). The underlying reason for this was hinted at by Georg Simmel who noted, “[a] deity that is subsumed into a unity with the whole of existence cannot possibly possess any power, because there would be no separate object to which He could apply such power” ([

46], p.53). In other words, it comes down to whether God is believed to be an independent actor/collaborator in world affairs. Armed with this image of God, we expect a religion to matter greatly in political and social change.

Stark has demonstrated that belief in God is associated with moral policy disputes across Europe and in India, Turkey, and the United States; but the relationship does not hold in China or Japan [

47]. Stark concludes that God is politically unimportant in China and Japan because God is generally regarded as “unconcerned about morality, or as an impersonal essence” in these religious cultures ([

47], p. 624). Similarly, majority monotheistic nations are far more likely to ban genetic research than countries with Hindu or Buddhist traditions. Molecular biologist Lee Silver speculates:

[M]ost people in Hindu and Buddhist countries have a root tradition in which there is no single creator God. Instead, there may be no gods or many gods, and there is no master plan for the universe. Instead, spirits are eternal and individual virtue—karma—determines what happens to your spirit in your next life. With some exceptions, this view generally allows the acceptance of both embryo research to support life and genetically modify crops.

Looking specifically inside the United States, Andrew Greeley found that Americans with more maternal and gracious conceptions of God were more likely to vote Democrat, support “safe sex” education, support environmental protection, and oppose the death penalty [

49,

50,

51,

52,

53]. Overall, Greeley finds significant correlations between viewing God as a mother, lover or friend and being politically liberal. Greeley’s findings fit with more recent arguments by George Lakoff and Wayne Baker about the opposing moral cultures of American liberals and conservatives [

28,

54]. Lakoff asserts that liberals express a “Nurturant Parent” morality (similar to Greeley’s loving motherly God) while conservatives reference a “Strict Father” morality—a prioritizing of obedience over independence. Perhaps President Clinton summarized this perspective best when he explained that “liberals want to fall in love, and conservatives want to fall in line”. The general view is that conservatives tend towards a stricter moral absolutism while liberals tend towards flexible moral humanism, both of which are reflected in the kinds of gods they worship.

These theoretical and empirical extracts suggest that investigating the role of God in politics around the world may bear more fruit. Specifically, past research suggests that more active and engaged Gods (a) will inspire human sacrifice for religious causes, be they altruistic or militaristic; and also (b) inspire strict moral codes of acceptable behavior.

Still, this may get us little further than Weber’s initial insight about the political potential of various theologies. In other words, we can identify which religious concepts are correlated with sacrifice and moral absolutism but can do little to predict what forms of sacrifice and moralism they inspire. It seems that the cultural and political context is primary. For instance, in a culture in which moral issue X is salient, we will expect religious believers in an engaged God to be more absolutist on this issue. The relationship between genetic research laws and monotheism around the world is one piece of supporting evidence. Or if nation Y is at war with nation Z, we would expect citizens with an engaged God to be more willing to fight unless they are part of a strictly pacifist tradition; and if one nation has a more engaged God, we might expect that nation to be more vicious and resilient in its war effort. In historical studies of Christian and Muslim intolerance, Stark has shown how external conflict is “inherent” to monotheisms [

45]. To better explore these ideas, we require better data and more precise theories.

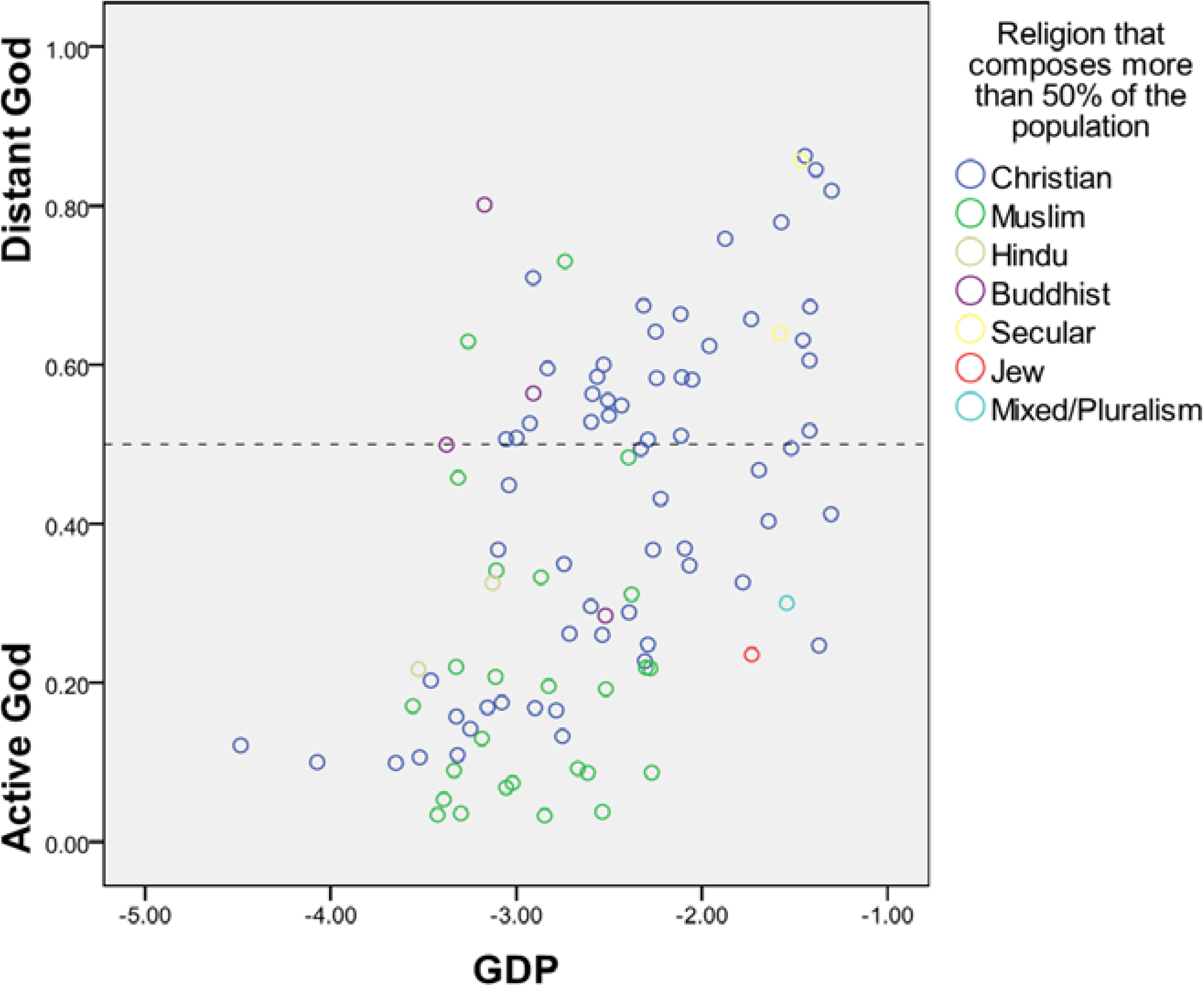

I suggest that a good place to begin is by looking at cross-cultural data on images of God. “God” tends to be a concept understood in many cultures, albeit in vastly different forms. Stark highlights the importance of a God’s scope and responsiveness. The World Values Survey and the International Social Survey Program have some questions about God which may be of use. But I have been lucky enough to place a God item on the Gallup World Poll, one of the most inclusive international datasets including over 140 countries. While this is only a single variable, it provides a glimpse of God’s scope and responsiveness—specifically, the question asks, “do you believe that God is directly involved in things that happen in the world?” By averaging responses to this question, we can classify nations by their popular image of God. On one end we have nations in which most individuals see God as a distant cosmic force and at the other end are nations in which the population thinks of God as active in world affairs. This is one of the best, albeit limited, indicators of whether theology can be used in political arguments; if believers think God is engaged in the outcome of political history, they are more apt to accept political rhetoric which appeals to God.

Figure 2 displays these mean God scores in relationship to the per capita GDP and the majority religion of each country. Three initial findings present themselves. First, majority Muslim countries tend to have much more active Gods than majority Christian nations. This may be a function of modernization, because, second, countries with lower per capita GDP tend to have more active Gods. And third, the United States stands as an outlier to these two general trends. Namely, the United States has one of the most active Gods in comparison to other majority-Christian nations and the most active God in comparison to nations with the highest per capita GDP.

Figure 2.

God around the World (correlated with per capita GDP).

Figure 2.

God around the World (correlated with per capita GDP).

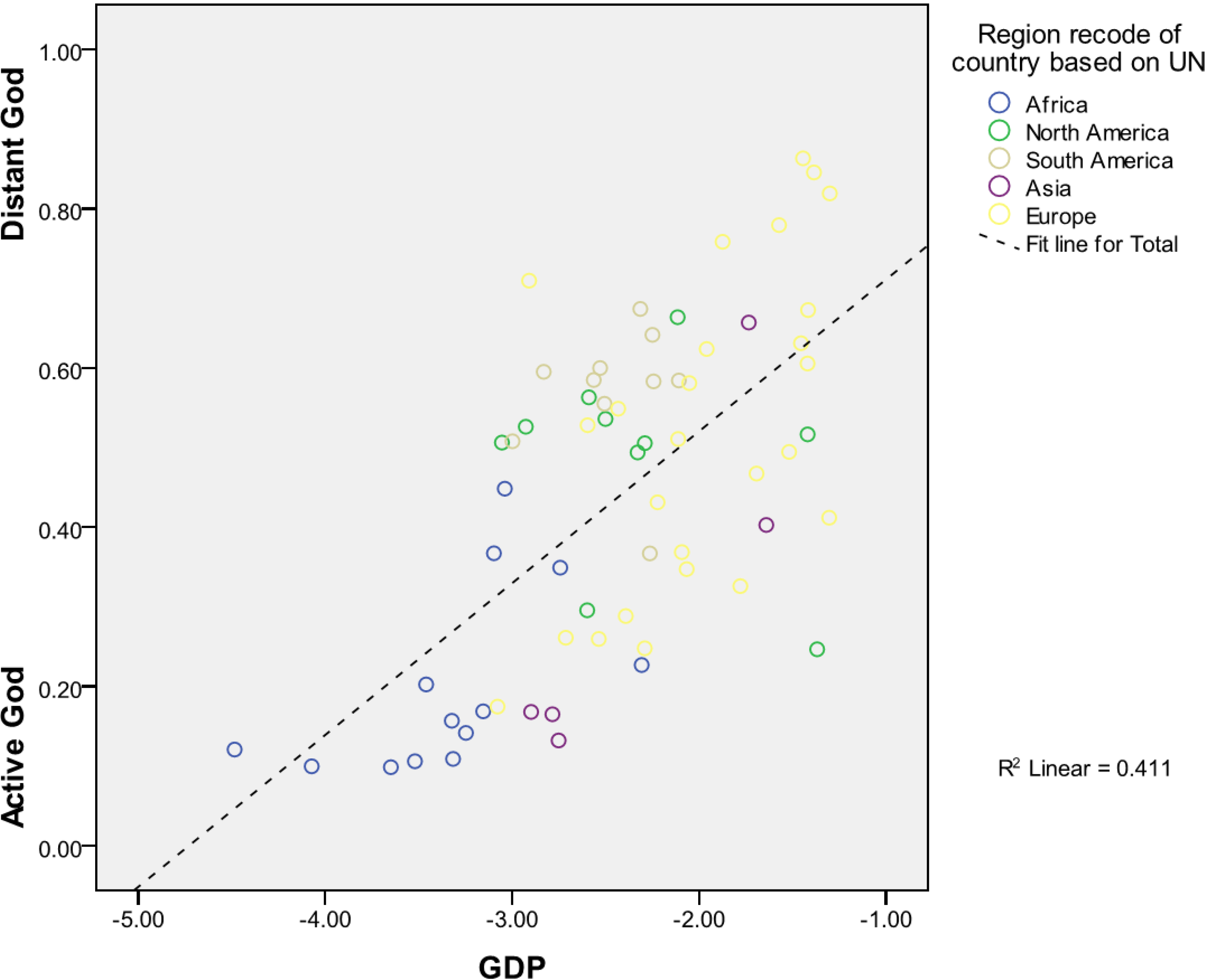

Figure 3 again highlights American exceptionalism by comparing the United States to other majority-Christian nations. The United States most closely resembles African Christian nations in their active images of God. Europeans stand in direct contrast with some of the most distant images of God; and this finding was replicated using God items from the International Social Survey Program [

33,

42].

This data provides many research possibilities. First, the clear relationship between a nation’s type of God and its level of economic development suggests a causal pattern. Perhaps this is a new way to think about the process of secularization; it is

not a transition from religiosity to secularity but rather a move from a theological tradition which asserts that God engages in the world to a theological tradition which voluntarily resigns the scientific, political, and professional realms to their own philosophical devices. Based on levels of affiliation and church attendance, the United States is often mentioned as an exception to a general trend toward secularization which is occurring in most postindustrial countries [

55,

56,

57,

58].

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 indicate that the United States is also exceptional because Americans believe in a kind of God which is mainly confined to pre-industrial and industrial societies.

Figure 3.

God around the Christian World (correlated with per capita GDP).

Figure 3.

God around the Christian World (correlated with per capita GDP).

To put a finer point on this abstraction, I feel that images of God are really a measure of the extent to which believers feel that God is a political and social actor—in other words, it is a measure of sacralization ideology. Religions with active and engaged Gods demand a political say, while religions with “cosmic forces”, “personal enlightenment”, or countless deities will have little interest in religious politics outside of protecting their right to worship. If this is the case, then we can begin to see why religion continues to play an active role in American politics—American religion is politically important because many Americans think that God is actively involved in it and, in fact, guiding it.

5. God and American Politics

The book

America’s Four Gods (2010) is an attempt to understand the importance and meaning of Americans’ images of God. In general, Chris Bader and I find that images of God are directly related to how an American understands sex, science, economics, and patriotism [

42]. These issues are at the heart of contemporary American political debates and are especially relevant in the formation of identity politics.

While God is important, scriptural disputes surprisingly are not. Approximately 60 million Americans think the Bible “should be taken literally, word-for-word, on all subjects”; in other words, these people are

Biblical Literalists. However, simply reading of the Bible does not tell you what these Americans believe. This is because Biblical Literalism is first and foremost an identity and not a clear set of beliefs [

59]. The main theological belief that is statistically associated with Biblical Literalism is faith in an active and engaged God. Simply put, Biblical Literalism is a group marker that mainly indicates that the person thinks God interacts with the contemporary world in the same way He does in Biblical stories. It can be through wrath, love, or spoken revelation. In some paradoxical way, Biblical Literalists are less reliant on the Bible because its Divine author is thought to be always around and open to conversation.

Consequently, the political fervor and perspective of Biblical Literalists is less about carrying out the directives of scripture and more about allying with believers who share their image of God and their sense of His presence. For this reason, the political manipulation of these kinds of religionists takes the form of religious posturing and not theological dogmatism. A political candidate need not appear slavishly devoted to Biblical mandates but rather should appear in dialogue with God. In this way, political leaders do not have to link their policy ideas to scripture but, rather, need to successfully communicate that their decision-making is informed by heart-felt prayer. And American political leaders are eager to tell us that they are in dialogue with God. As Domke and Coe assert, “the substantial presence of God and faith in American politics over the past few decades did not occur by chance…The God strategy is operating in full force, and many, many Americans are on board” ([

9], p. 33).

And between the only viable American political parties, the GOP is the undisputed champion of the God strategy. But why? I do not think that a conservative platform is philosophically more compatible with belief in an engaged God. Leftist social, economic, and foreign policy easily could be seen to be working with and through God. This is the belief system of religious socialists and communists known as “liberation theology”; this ideology asserts that God smiles approvingly on a controlled economy and a classless society. But this is certainly not the case in the United States.

An active American God appears unapologetically conservative on all counts. Domke and Coe find that Republican political leaders are much more likely than Democrats to “fuse God and country by linking America with divine will” ([

9], p. 19). I expect that the Democratic Party is unwilling to employ such overt religious rhetoric for fear that it would sound too exclusionary, while the Republican Party appears to have no fear in this regards. They clearly define their enemies as “godless” which, in this usage, does not indicate atheism but rather that someone may hold a different image of God—a God which is not so closely allied with American national interests.

The aligning of conservative politics with an active God makes sense philosophically and politically. Philosophically, an active God takes sides in worldly affairs, favoring the good and condemning the bad. If this is the case, then believers naturally ponder which nations and citizens are God’s favored; and the answer is obvious—us. In contrast, believers in a distant God do not think in terms of God’s favored people; for these believers, God does not pick sides and therefore cannot be described as favoring one nation over another. Politically, the Democratic Party is also hoping to appeal to Americans of all religious and non-religious ilks. For this reason, they are careful to employ the most ecumenical religious language possible, which strikes many believers in an active God as insincere due to its avoidance of clear dividing lines.

In the end, this is how religion remains a political force in the United States. The Republican Party appeals to a certain type of religious believer—one who believes that God is a political actor. In turn, the GOP must address or at least appear to address religious issues which concern these believers. While abortion and gay marriage are the most salient of these issues, believers in an active God have also come to think of political leaders who fervently employ the God strategy as having some holy mandate in

all of their political dealings. Past support for the Iraq War is one of the clearest cases of this phenomenon [

40]. In this instance, justification for this foreign policy was premised mainly on the narrative that America, with God’s help, was fighting evil in the world. Americans that believed this framing never gave up on the war, while other conservatives abandoned it in droves as casualties mounted [

40].