Work-Family Conflict: The Effects of Religious Context on Married Women’s Participation in the Labor Force

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Women and Work/Family Conflict

2.2. Family and Religion

2.3. Religious Context

- Hypothesis 1a: The religious context of an area will have an effect on the proportion of women who have families and are not in the labor force.

- Hypothesis 1b: Areas with higher concentrations of conservative religious groups (such as Catholics and evangelicals) will have more women with families who are not in the labor force.

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Analytic Method

3.2. Measures

| Mean/Prop. | St. Dev. | Min. | Max. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Religious Context Variables | ||||

| Evangelical | 0.124 | 0.104 | 0.002 | 0.637 |

| Mainline Protestant | 0.067 | 0.055 | 0.000 | 0.581 |

| Black Protestant | 0.014 | 0.032 | 0.000 | 0.444 |

| Catholic | 0.101 | 0.083 | 0.000 | 0.827 |

| Jewish | 0.003 | 0.008 | 0.000 | 0.128 |

| Mormon | 0.005 | 0.019 | 0.000 | 0.332 |

| Other | 0.040 | 0.035 | 0.000 | 0.597 |

| Herfandel Index | 0.656 | 0.106 | 0.144 | 0.864 |

| PUMA Level Variables | ||||

| Has Children | 0.416 | 0.073 | 0.114 | 0.688 |

| Education | 10.548 | 1.008 | 5.802 | 13.812 |

| Adjusted Wages | 10.383 | 0.249 | 9.695 | 11.518 |

| Age | 44.260 | 1.680 | 35.000 | 51.000 |

| Gender | 0.496 | 0.011 | 0.436 | 0.564 |

| Race | 0.787 | 0.191 | 0.020 | 0.991 |

| Dependent Variable | ||||

| Women in the Labor Force | 0.619 | 0.062 | 0.272 | 0.807 |

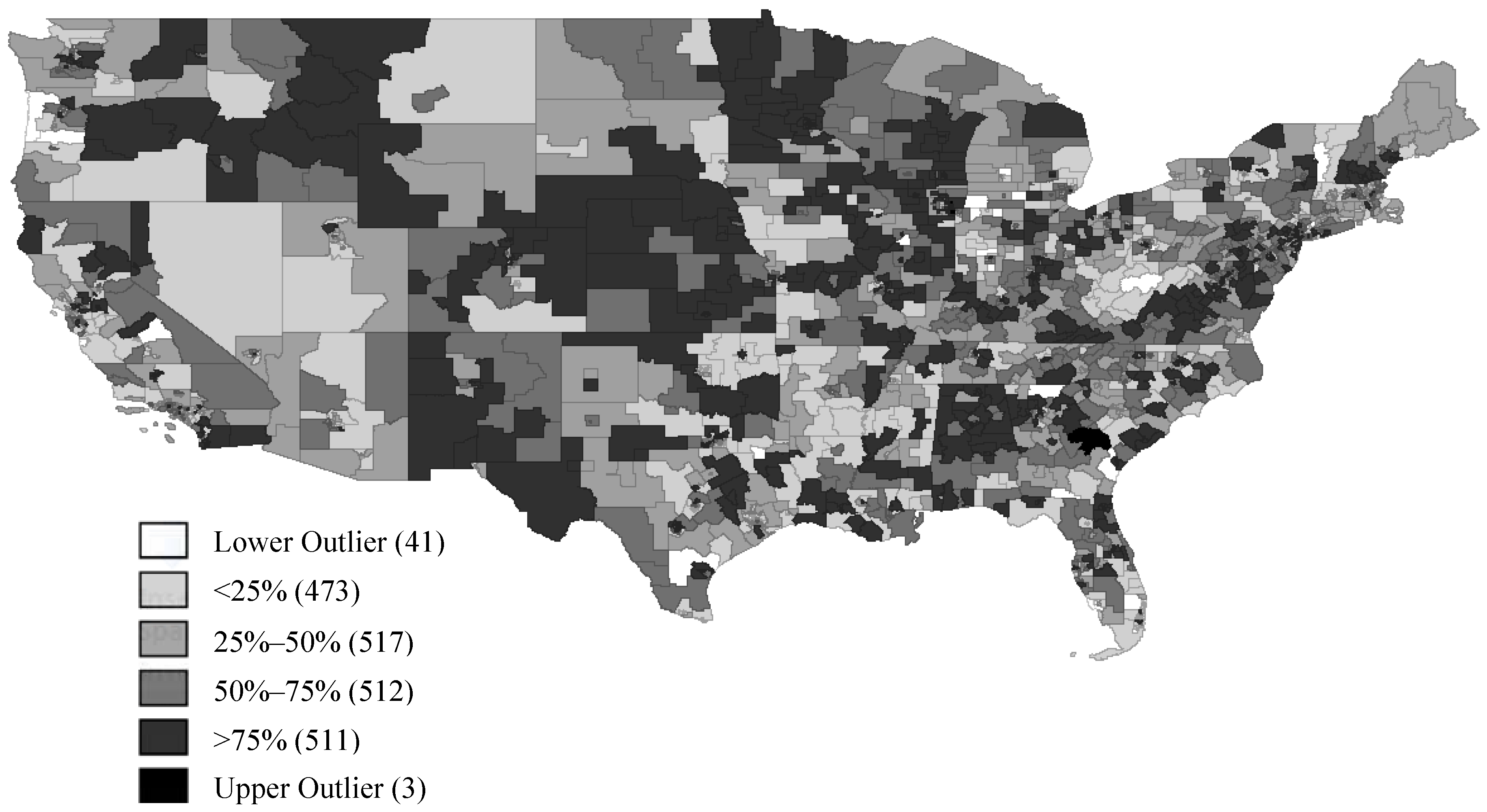

4. Results

| Estimate | Std. Error | |

|---|---|---|

| Constant | −0.283 * | 0.033 |

| Spatial Weight | 0.335 * | 0.023 |

| Religious Context | ||

| Proportion Evangelical | −0.035 * | 0.016 |

| Proportion Mainline Protestant | 0.221* | 0.023 |

| Proportion Black Protestant | 0.069 | 0.041 |

| Proportion Catholic | 0.02 | 0.016 |

| Proportion Jewish | −1.42 * | 0.141 |

| Proportion Mormon | −0.201 * | 0.057 |

| Proportion Other | −0.024 | 0.033 |

| Herfandel Index | −0.013 | 0.013 |

| PUMA Averages | ||

| Has Children | 0.162 * | 0.022 |

| Education | 0.030 * | 0.002 |

| Adjusted Wages | 0.014 | 0.008 |

| Age | −0.003 * | 0.001 |

| Gender | 0.633 * | 0.094 |

| Race (White) | −0.037 * | 0.008 |

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mary Blair-Loy. Competing Devotions: Career and Family among Women Executives. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Anne H. Gauthier, Timothy M. Smeedeng, and Frank F. Furstenberg. “Are Parents Investing Less Time in Children? Trends in Selected Industrialized Countries.” Population and Development Review 30 (2004): 647–71. [Google Scholar]

- Annette Lareau. Unequal Childhoods: Class, Race and Family Life. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Liana C. Sayer. “Gender, Time and Inequality: Trends in Women’s and Men’s Paid Work, Unpaid Work and Free Time.” Social Forces 84 (2005): 285–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzanne M. Bianchi, and Sara Raley. “Time Allocation in Families.” In Work, Family, Health and Well-Being. Edited by Suzanne M. Bianchi, Lynne M. Casper and Rosalind B. King. Philadelphia: Erlbaum, 2005, pp. 21–42. [Google Scholar]

- Judy Koenigsberg, Michael S. Garet, and James E. Rosenbaum. “The Effects of Family on Job Exits of Young Adults: A Competing Risk Model.” Work and Occupations 21 (1994): 33–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samantha K. Ammons, and Penny Edgell. “Religious Influences on Work-Family Trade-Offs.” Journal of Family Issues 28 (2007): 794–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margaret L. Bendroth. Growing Up Protestant: Parents, Children and Mainline Churches. Piscataway: Rutgers University Press, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kevin Christiano. “Religion and Family in Modern American Culture.” In Family, Religion and Social Change in Diverse Societies. Edited by Jerry G. Pankhurst and Sharon K. Houseknecht. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000, pp. 43–78. [Google Scholar]

- Penny Edgell. Religion and Family in a Changing Society. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Darren E. Sherkat, and Christopher G. Ellison. “Recent Developments and Current Controversies in the Sociology of Religion.” Annual Review of Sociology 25 (1999): 363–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodney Stark. “Religion and Conformity: Reaffirming a Sociology of Religion.” Sociological Analysis 45 (1984): 273–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzanne M. Bianchi, and Melissa Milkie. “Work and Family Research in the First Decade of the 21st Century.” Journal of Marriage and Family 72 (2010): 705–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerry Jacobs, and Kathleen Gerson. “Overworked Individuals or Overworked Families? ” Work and Occupations 28 (2001): 40–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelle J. Budig, and Paula England. “The Wage Penalty for Motherhood.” American Sociological Review 66 (2001): 204–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynn Craig. “Does Father Care Mean Fathers Share? A Comparison of How Mothers and Fathers in Intact Families Spend Time with Children.” Gender and Society 20 (2006): 259–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gina M. Bellavia, and Michael R. Frone. “Work-Family Conflict.” In Handbook of Work Stress. Edited by Julian Barling, Kevin Kelloway and Michael R. Frone. California: Sage Publications, 2005, pp. 113–48. [Google Scholar]

- Dave Elder-Vass. “Integrating Institutional, Relational and Embodied Structure: An Emergentist Perspective.” The British Journal of Sociology 59 (2008): 281–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisa A. Keister. Faith and Money: How Religion Contributes to Wealth and Money. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Samuel Stroope. “Education and Religion: Individual, Congregational, and Cross-level Interaction Effects on Biblical Literalism.” Social Science Research 40 (2011): 1478–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughn R. Call, and Tim B. Heaton. “Religious Influence on Marital Stability.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 36 (1997): 382–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher G. Ellison, and Darren E. Sherkat. “Obedience and Autonomy: Religion and Parental Values Reconsidered.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 32 (1993): 313–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tim B. Heaton, and Marie Cornwall. “Religious Group Variation in the Socioeconomic Status and Family Behavior of Women.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 28 (1989): 283–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willaim D. Mosher, and Gerry E. Hendershot. “Religious Affiliation and the Fertility of Married Couples.” Journal of Marriage and Family 46 (1984): 671–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W. Bradford Wilcox. “Conservative Protestant Childrearing: Authoritarian or Authoritative? ” American Sociological Review 63 (1998): 796–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John Bartkowski. “One Step Forward, One Step Back: ‘Progressive Traditionalism’ and the Negotiation of Domestic Labor in Evangelical Families.” Gender Issues 17 (1999): 37–61. [Google Scholar]

- John Bartkowski, and Jen’nan Read. “Veiled Submission: Gender, Power, and Identity among Evangelical and Muslim Women in the United States.” Qualitative Sociology 26 (2003): 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helen Hardacre. “The Impact of Fundamentalism on Women, the Family and Interpersonal Relations.” In Fundamentalisms and Society: Reclaiming the Sciences, the Family and Education. Edited by Martine E. Marty and Scott R. Appleby. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997, pp. 129–50. [Google Scholar]

- Harriet Hartman, and Moshe Hartman. “More Jewish, Less Jewish: Implications for Education and Labor Force Characteristics.” Sociology of Religion 57 (1996): 175–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evelyn L. Lehrer. “The Effects of Religion on the Labor Supply of Married Women.” Social Science Research 24 (1995): 281–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- William D. Mosher, Linda B. Williams, and David P. Johnson. “Religion and Fertility in the United States: New Patterns.” Demography 29 (1992): 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darren E. Sherkat. “That They Be Keepers of the Home: The Effect of Conservative Religion on Early and Late Transitions into Housewifery.” Review of Religious Research 4 (2000): 344–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clyde Wilcox, and Ted G. Jelen. “The Effects of Employment and Religion on Women’s Feminist Attitudes.” International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 1 (1991): 161–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margaret L. Bendroth. Fundamentalism and Gender, 1875 to the Present. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Elaine H. Ecklund. “Catholic Women Negotiate Feminism: A Research Note.” Sociology of Religion 64 (2003): 515–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sally. Gallagher. Evangelical Identity and Gendered Family Life. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sally Gallagher, and Christian Smith. “Symbolic Traditionalism and Pragmatic Egalitarianism: Contemporary Evangelicals, Families, and Gender.” Gender and Society 13 (1999): 211–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert D. Woodberry, and Christian S. Smith. “Fundamentalism et al: Conservative Protestants in America.” Annual Review of Sociology 24 (1998): 25–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyle C. Longest, Steven Hitlin, and Stephen Vaisey. “Position and Disposition: The Contextual Development of Human Values.” Social Forces 91 (2013): 1499–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennifer Johnson-Hanks, Christine A. Bachrach, S. Philip Morgan, and Hans-Peter Kohler. Understanding Family Change and Variation: Toward a Theory of Conjunctural Action. New York: Springer, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Margaret S. Archer, and Dave Elder-Vass. “Cultural System or Norm Circles? An Exchange.” European Journal of Social Theory 15 (2012): 93–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James K. Wellman, and Katie E. Corcoran. “Religion and Regional Culture: Embedding Religious Commitment within Place.” Sociology of Religion 74 (2013): 496–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert N. Bellah. Beyond Belief: Essays on Religion in a Post-Traditionalist World. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Emile Durkheim. The Elementary Forms of Religious Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Matthew R. Lee, and John Bartkowski. “Love Thy Neighbor? Moral Communities, Civic Engagement, and Juvenile Homicide in Rural Areas.” Social Forces 82 (2004): 1001–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mark D. Regnerus. “Moral Communities and Adolescent Delinquency.” Sociological Quarterly 44 (2003): 523–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodney Stark. “Religion as Context: Hellfire and Delinquency One More Time.” Sociology of Religion 57 (1996): 163–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martha Gault-Sherman, and Scott Draper. “What Will the Neighbors Think? The Effect of Moral Communities on Cohabitation.” Review of Religious Research 54 (2012): 45–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brian Steensland, Jerry Z. Park, Mark D. Regnerus, Lynn D. Robinson, W. Bradford Wilcox, and Robert D. Woodberry. “The Measure of American Religion: Toward Improving the State of the Art.” Social Forces 79 (2000): 291–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Gordon Melton. Melton’s Encyclopedia of American Religions, 8th ed. Detroit: Gale Cengage Learning, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Frank S. Mead, and Samuel S. Hill. Handbook of Denominations in the United States, 10th ed. Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- J. Gordon Melton. “Religion Family Trees.” The Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA). Available online: http://www.thearda.com/denoms/families/trees/index.asp (accessed on 15 February 2014).

- Tim B. Heaton, and Kristen L. Goodman. “Religion and Family Formation.” Review of Religious Research 26 (1985): 343–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffrey D. Morenoff. “Neighborhood Mechanisms and the Spatial Dynamics of Birth Weight.” American Journal of Sociology 108 (2003): 976–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luc Anselin. Exploring Spatial Data with GeoDa: A Workbook; Urbana: Center for Spatially Integrated Social Science, 2005. Available online: Available online: https://geodacenter.asu.edu/system/files/geodaworkbook.pdf (accessed on 11 July 2014).

- Steven F. Messner, and Luc Anselin. “Spatial Analysis of Homice with Areal Data.” In Spatially Integrated Social Science, Spatial Information Systems. Edited by Michael F. Goodchild and Donald G. Janelle. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Luc Anselin. “Spatial Externalities, Spatial Multipliers, and Spatial Econometrics.” International Regional Science Review 26 (2003): 153–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luc Anselin. Spatial Econometrics: Methods and Models. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Kyle Crowder, and Scott J. South. “Spatial Dynamics of White Flight: The Effects of Local and Extralocal Racial Conditions on Neighborhood Out-Migration.” American Sociological Review 73 (2008): 792–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffrey D. Morenoff, Robert J. Sampson, and Stephen W. Raudenbush. “Neighborhood Inequality, Collective Efficacy, and the Spatial Dynamics of Urban Violence.” Criminology 39 (2001): 517–59. [Google Scholar]

- Jennifer Glass, and Jerry Jacobs. “Childhood Religious Conservatism and Adult Attainment among Black and White Women.” Social Forces 84 (2005): 555–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evelyn L. Lehrer. “Religion as a Determinant of Economic and Demographic Behavior in the United States.” Population and Development Review 30 (2004): 707–26. [Google Scholar]

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Rogers, J.G.; Franzen, A.B. Work-Family Conflict: The Effects of Religious Context on Married Women’s Participation in the Labor Force. Religions 2014, 5, 580-593. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel5030580

Rogers JG, Franzen AB. Work-Family Conflict: The Effects of Religious Context on Married Women’s Participation in the Labor Force. Religions. 2014; 5(3):580-593. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel5030580

Chicago/Turabian StyleRogers, Jenna Griebel, and Aaron B. Franzen. 2014. "Work-Family Conflict: The Effects of Religious Context on Married Women’s Participation in the Labor Force" Religions 5, no. 3: 580-593. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel5030580

APA StyleRogers, J. G., & Franzen, A. B. (2014). Work-Family Conflict: The Effects of Religious Context on Married Women’s Participation in the Labor Force. Religions, 5(3), 580-593. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel5030580