Determinants of Disaffiliation: An International Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

| All countries | Europe | Non-Europe | |||||

| Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | ||

| DEPENDENT VARIABLE | |||||||

| Converted out (%) | 9.2 | 13.5 | 10.4 | 15.7 | 4.6 | 6.0 | |

| INDEPENDENT VARIABLES | |||||||

| COUNTRY VARIABLES | |||||||

| European country (%) | 79.6 | 78.0 | - | - | - | - | |

| Pluralism index (range of 0–1) | 0.37 (0.25) | 0.37 (0.25) | 0.33 (0.24) | 0.34 (0.24) | 0.50 (0.26) | 0.50 (0.29) | |

| State-religion (%) | 32.4 | 31.7 | 35.0 | 34.8 | 22.5 | 20.6 | |

| Average country church attendance (att.) | 2.15 (0.78) | 2.13 (0.77) | 2.11 (0.76) | 2.08 (0.76) | 2.35 (0.79) | 2.34 (0.79) | |

| Per capita GDP (US$) | 15494.14 | 15942.90 | 15361.43 | 15761.74 | - | - | |

| (10319.1) | (10486.8) | (10250.3) | (10381.1) | ||||

| PERSONAL ATTRIBUTES | |||||||

| Religious denomination (raised in) | |||||||

| Catholic (%) | 57.2 | 55.1 | 64.1 | 59.5 | 39.4 | 39.9 | |

| Jewish (%) | 4.3 | 4.3 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 21.0 | 18.9 | |

| Moslem (%) | 0.8 | 1.4 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 2.1 | 2.9 | |

| Protestant (%) | 27.8 | 28.6 | 24.4 | 28.6 | 29.5 | 28.4 | |

| Orthodox (%) | 7.7 | 7.4 | 9.8 | 9.4 | 0.2 | 0.2 | |

| Other Christian (%) | 1.3 | 1.6 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 4.0 | 4.1 | |

| Other non-Christian (%) | 0.9 | 1.6 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 3.8 | 5.6 | |

| Religion homogamous house (%) | 89.9 | 90.8 | 91.7 | 92.1 | 83.1 | 86.0 | |

| Intensive church att. at 12 (%) | 56.8 | 50.6 | 56.5 | 50.0 | 57.7 | 52.9 | |

| Age | 45.64 (15.17) | 48.95 (15.21) | 45.97 (15.25) | 49.02 (15.24) | 44.35 (14.78) | 48.71 (15.11) | |

| Last school attended | |||||||

| Elementary (%) | 25.1 | 24.4 | 27.5 | 26.0 | 16.1 | 18.4 | |

| High School (%) | 39.7 | 39.5 | 38.6 | 39.1 | 43.9 | 41.1 | |

| Academic (%) | 35.2 | 36.1 | 33.9 | 34.9 | 40.0 | 40.5 | |

| “Extramarital sex relations” view | |||||||

| Always wrong (%) | 67.9 | 59.0 | 65.2 | 55.3 | 78.3 | 71.9 | |

| Almost always wrong (%) | 19.9 | 23.3 | 20.7 | 24.8 | 16.8 | 17.9 | |

| Wrong only sometimes (%) | 8.9 | 12.1 | 10.2 | 13.5 | 4.0 | 7.3 | |

| Not wrong at all (%) | 3.3 | 5.6 | 3.9 | 6.4 | 0.9 | 2.9 | |

| “Homosexual relations” view | |||||||

| Always wrong (%) | 53.5 | 59.0 | 50.9 | 56.2 | 63.5 | 68.6 | |

| Almost always wrong (%) | 8.6 | 9.6 | 8.7 | 10.0 | 8.4 | 8.2 | |

| Wrong only sometimes (%) | 11.3 | 10.1 | 12.0 | 10.7 | 8.6 | 8.1 | |

| Not wrong at all (%) | 26.6 | 21.3 | 28.4 | 23.1 | 19.5 | 15.1 | |

| Believe in Heaven | |||||||

| Yes, definitely (%) | 37.2 | 29.5 | 32.7 | 25.0 | 54.5 | 45.5 | |

| Yes, probably (%) | 28.4 | 24.4 | 29.3 | 24.1 | 25.2 | 25.3 | |

| No, probably not (%) | 15.8 | 17.8 | 17.1 | 19.1 | 10.8 | 13.2 | |

| No, definitely not (%) | 18.6 | 28.3 | 20.9 | 31.8 | 9.5 | 16.0 | |

| Believe in Hell | |||||||

| Yes, definitely (%) | 28.6 | 23.3 | 24.5 | 18.8 | 44.5 | 39.4 | |

| Yes, probably (%) | 22.4 | 20.1 | 22.3 | 19.5 | 22.9 | 22.0 | |

| No, probably not (%) | 20.3 | 21.0 | 21.3 | 22.0 | 16.5 | 17.6 | |

| No, definitely not (%) | 28.7 | 35.6 | 31.9 | 39.7 | 16.1 | 21.0 | |

| Believe in Miracles | |||||||

| Yes, definitely (%) | 33.5 | 25.5 | 31.2 | 23.0 | 42.4 | 34.1 | |

| Yes, probably (%) | 29.0 | 26.7 | 29.3 | 26.4 | 28.0 | 27.8 | |

| No, probably not (%) | 17.6 | 19.5 | 18.1 | 19.9 | 15.6 | 18.1 | |

| No, definitely not (%) | 19.9 | 28.3 | 21.4 | 30.7 | 14.0 | 20.0 | |

| MARRIAGE ATTRIBUTES | |||||||

| Married (%) | 85.6 | 89.2 | 83.9 | 88.1 | 92.2 | 93.2 | |

| Spouse has same religion as respondent was raised in (%) | 79.4 | 81.8 | 79.5 | 81.5 | 79.0 | 82.9 | |

| Spouse has 'no religion' (%) | 7.2 | 5.7 | 7.4 | 6.4 | 6.2 | 3.5 | |

| Sample Size | 7895 | 7258 | 6287 | 5660 | 1608 | 1598 | |

2. Dataset, Variables and Methodology

2.1. Sample and Dataset

2.2. Variables

2.2.1. The Dependent Variable

= 0 otherwise

2.2.2. Country-Specific Variables

- The country average level of church (religious services) attendance: the variable “church attendance” is measured on a scale of 1-to-6, ranging from ‘not attending at all’ to ‘attending at least once a week’.8 Using this variable, the country average has been calculated. The country average is a continuous variable. Another indicator of the country-level religiosity is the average prayer level (scale of 1–11). However, adding this variable led to multicollinearity, due to a high correlation between country average church attendance and country-average prayer (a correlation coefficient of 0.84).

2.2.3. Personal Attributes

- Present age: obviously, the more relevant variable is the age of disaffiliation and not the current age. Unfortunately, respondents were not asked when they converted out.9 We also include age-squared to allow for a non-linear (parabolic) relationship;

- Education: last school attended; elementary (reference category); high school; and academic education institution.

- One is related to extra-marital sexual relations. The question’s phrasing was: for a married person to have sexual relations with someone other than her/his husband or wife is: (1) always wrong (reference category); (2) almost always wrong; (3) wrong only sometimes; or (4) not wrong at all.

- The other question refers to homosexual relations: sexual relations between two adults of the same sex is: (same four options as above.)

- Religious denomination in which the subject was educated;

- Using information regarding the religious affiliation of the father and mother, we defined the variable: raised in a religious homogamous household, that equals 1 if the father and mother had the same religion (when the respondent was a child);

- Information on exposure to church (religious) services during childhood, that includes nine alternative levels, was used to define the dummy variable: intensive religious practice during childhood = 1,10 for original values of: seven (attended almost every week), eight (every week) and nine (several times a week).

- Belief in heaven;

- Belief in hell;

- Belief in miracles.

2.2.4. Marriage Effects

- Marital status (married = 1; 0 otherwise);

- Spouse has the same denomination as the respondent was raised in;

- Spouse has 'no religion'.

2.3. Method

3. Findings

3.1. Descriptive Statistics: Sample Characteristics

3.2. Regression Results

| All countries | Europe | No Europe | ||||||||||

| Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | |||||||

| COUNTRY-SPECIFIC VARIABLES | ||||||||||||

| a) Religious strictness | ||||||||||||

| Residence in a European country | 4.23 (0.030) | 7.29 (0.004) | - | - | - | - | ||||||

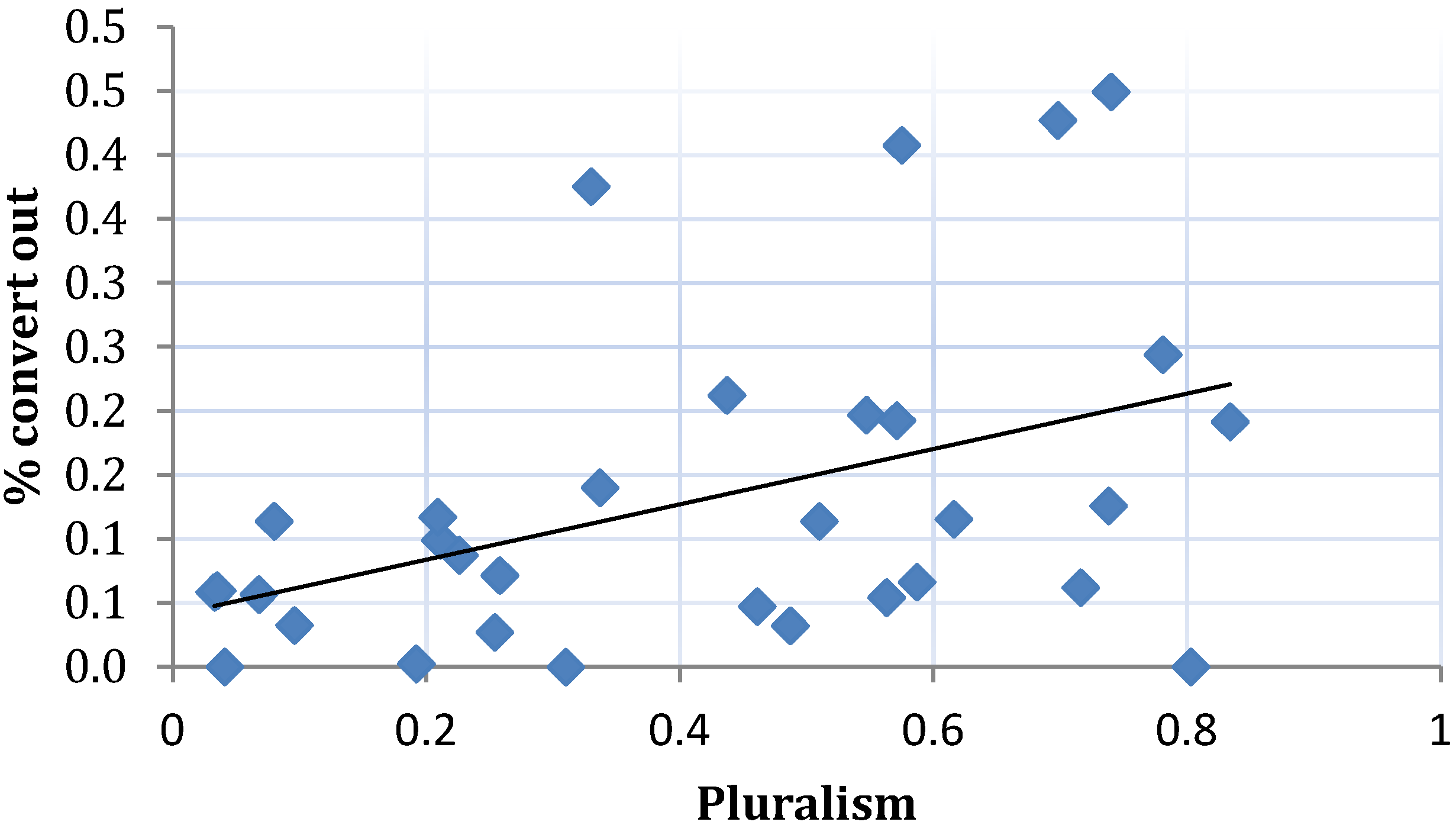

| Pluralism index | 10.54 (0.039) | 11.93 (0.04) | 6.48 (0.065) | 7.40 (0.093) | 3.63 (0.886) | 3722.72 (0.177) | ||||||

| State religion | 0.70 (0.514) | 0.81 (0.732) | 0.86 (0.749) | 1.00 (0.998) | 0.00 (1.000) | 0.00 (1.000) | ||||||

| b)Religious adherence | ||||||||||||

| Country average Mass | 1.06 (0.865) | 1.59 (0.212) | 0.92 (0.803) | 1.38 (0.369) | 0.46 (0.778) | 10.51 (0.193) | ||||||

| c)GDP/1,000 | 1.04 (0.075) | 1.04 (0.100) | 1.03 (0.142) | 1.04 (0.115) | - | - | ||||||

| PERSONAL ATTRIBUTES | ||||||||||||

| a) Religion (raised in) | ||||||||||||

| Denomination Catholic | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||||

| Jewish | 0.48 (0.459) | 0.37 (0.226) | 0.00 (1.000) | 2.14 (0.521) | 7.84 (0.182) | 0.00 (1.000) | ||||||

| Moslem | 1.42 (0.682) | 0.96 (0.950) | 0.53 (0.581) | 0.59 (0.536) | 29.01 (0.017) | 7.58 (0.105) | ||||||

| Protestant | 1.20 (0.197) | 0.71 (0.017) | 1.02 (0.907) | 0.59 (0.001) | 2.65 (0.036) | 2.11 (0.072) | ||||||

| Orthodox | 1.45 (0.422) | 2.85 (0.015) | 1.25 (0.642) | 2.52 (0.044) | 0.00 (1.000) | 0.00 (1.000) | ||||||

| Other Christian | 2.27 (0.081) | 2.63 (0.011) | 2.42 (0.071) | 2.01 (0.090) | 1.02 (0.994) | 24.40 (0.003) | ||||||

| Other non-Christian | 1.88 (0.277) | 2.79 (0.060) | 1.960 (0.319) | 2.16 (0.220) | 1.20 (0.950) | 36.44 (0.012) | ||||||

| Religiously homogamous household | 0.75 (0.038) | 0.55 (0.000) | 0.81 (0.175) | 0.51 (0.000) | 0.38 (0.018) | 0.86 (0.717) | ||||||

| Intensive church attendance at 12 | 0.80 (0.052) | 0.64 (0.000) | 0.78 (0.045) | 0.59 (0.000) | 0.88 (0.768) | 0.79 (0.507) | ||||||

| b) Socio-demographic attributes | ||||||||||||

| Age | 1.03 (0.191) | 1.00 (0.869) | 1.02 (0.486) | 1.00 (0.860) | 1.37 (0.007) | 1.22 (0.021) | ||||||

| Age squared | 1.00 (0.078) | 1.00 (0.550) | 1.00 (0.226) | 1.00 (0.803) | 1.00 (0.008) | 1.00 (0.025) | ||||||

| Last school attended Elementary | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||||

| High School | 0.96 (0.810) | 1.27 (0.102) | 0.94 (0.713) | 1.28 (0.098) | Ref. | 0.55 (0.403) | ||||||

| Academic | 1.00 (0.995) | 1.38 (0.032) | 0.94 (0.736) | 1.42 (0.023) | 1.66 (0.261) | 0.67 (0.561) | ||||||

| c) Beliefs | ||||||||||||

| “Extra-marital sex” view Always wrong | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||||

| Almost always wrong | 0.99 (0.918) | 1.40 (0.003) | 0.97 (0.845) | 1.30 (0.031) | 1.10 (0.832) | 2.84 (0.005) | ||||||

| Wrong only sometimes | 1.69 (0.001) | 1.62 (0.000) | 1.69 (0.001) | 1.70 (0.000) | 1.41 (0.616) | 0.91 (0.859) | ||||||

| Not wrong at all | 2.11 (0.001) | 1.63 (0.007) | 2.10 (0.002) | 1.80 (0.001) | 4.49 (0.310) | 0.08 (0.029) | ||||||

| “Homosexual relationship” view Always wrong | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||||

| Almost always wrong | 0.85 (0.468) | 1.35 (0.064) | 0.92 (0.698) | 1.39 (0.053) | 0.29 (0.184) | 1.31 (0.630) | ||||||

| Wrong only sometimes | 1.19 (0.297) | 1.27 (0.120) | 1.18 (0.364) | 1.25 (0.175) | 1.35 (0.611) | 1.60 (0.396) | ||||||

| Not wrong at all | 1.82 (0.000) | 1.69 (0.000) | 1.82 (0.000) | 1.66 (0.000) | 1.97 (0.183) | 2.92 (0.014) | ||||||

| Believe in Heaven Yes, definitely | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||||

| Yes, probably | 1.47 (0.136) | 1.55 (0.171) | 1.46 (0.176) | 1.70 (0.127) | 0.93 (0.919) | 2.01 (0.454) | ||||||

| No, probably not | 3.19 (0.000) | 4.02 (0.000) | 2.66 (0.001) | 3.86 (0.000) | 15.55 (0.000) | 7.63 (0.072) | ||||||

| No, definitely not | 6.18 (0.000) | 8.52 (0.000) | 5.78 (0.000) | 7.37 (0.000) | 14.50 (0.005) | 125.76 (0.000) | ||||||

| Believe in Hell Yes, definitely | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||||

| Yes, probably | 0.99 (0.991) | 0.63 (0.206) | 0.94 (0.850) | 0.59 (0.193) | 1.30 (0.776) | 0.31 (0.198) | ||||||

| No, probably not | 0.96 (0.885) | 0.60 (0.153) | 1.02 (0.945) | 0.69 (0.333) | 0.52 (0.454) | 0.12 (0.063) | ||||||

| No, definitely not | 1.03 (0.923) | 0.55 (0.070) | 0.99 (0.968) | 0.68 (0.277) | 1.18 (0.865) | 0.024 (0.002) | ||||||

| Believe in Miracles Yes, definitely | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||||

| Yes, probably | 1.11 (0.624) | 1.55 (0.071) | 0.98 (0.942) | 1.46 (0.136) | 2.47 (0.170) | 4.24 (0.056) | ||||||

| No, probably not | 1.85 (0.005) | 2.29 (0.001) | 1.78 (0.012) | 2.06 (0.005) | 2.22 (0.258) | 7.84 (0.009) | ||||||

| No, definitely not | 2.31 (0.000) | 4.12 (0.000) | 2.26 (0.000) | 3.79 (0.000) | 2.46 (0.263) | 16.95 (0.001) | ||||||

| MARRIAGE EFFECTS | ||||||||||||

| Married | 0.48 (0.000) | 0.57 (0.000) | 0.46 (0.000) | 0.59 (0.001) | 2.60 (0.245) | 0.51 (0.297) | ||||||

| Spouse has same religion as respondent was raised in | 0.43 (0.000) | 0.37 (0.000) | 0.44 (0.000) | 0.36 (0.000) | 0.28 (0.007) | 0.35 (0.009) | ||||||

| Spouse has 'no religion' | 4.23 (0.000) | 6.01 (0.000) | 4.13 (0.000) | 5.77 (0.000) | 6.44 (0.000) | 9.32 (0.000) | ||||||

| SAMPLE SIZE | 7895 | 7258 | 6287 | 5660 | 1608 | 1598 | ||||||

| AIC | 2975 | 3455 | 2672 | 3076 | 309 | 387 | ||||||

| BIC | 3233 | 3710 | 2915 | 3315 | 492 | 576 | ||||||

| Joint significance of age Χ2 (p-value) | 8.27 (0.016) | 6.10 (0.047) | 8.53 (0.014) | 5.67 (0.059) | 7.37 (0.025) | 5.41 (0.067) | ||||||

4. Concluding Remarks

- i

- strongly correlated with parental household religious homogamy;

- ii

- strongly correlated with the spouse's religious characteristics;

- iii

- highly correlated with beliefs and personal views;

- iv

- but, only marginally correlated with personal socio-economic features and with country features, except for the country religious diversity, which has a positive effect

| (+) effects | (-) effects |

|---|---|

| Country effects | |

| Residence in a European country | |

| Religious Pluralism | |

| Personal attributes | |

| Orthodox (males) | Protestant (males) |

| Academic education (males) | Homogamous parental households |

| Liberal views | Intensive church attendance at 12 |

| Religious disbeliefs | |

| Marriage effects | |

| Spouse has 'no religion' | Married |

| Spouse same religion | |

| MODEL 1 | MODEL 2 | MODEL 3 | MODEL 4 | MODEL 5 | MODEL 6 | |

| COUNTRY SPECIFIC VARIABLES | X | X | X | X | X | |

| RELIGION VARIABLES | X | X | X | X | X | |

| SOCIO-DEMO VARIABLES | X | X | X | X | X | |

| BELIEF VARIABLES | X | X | X | X | X | |

| MARIAGE VARIABLES | X | X | X | X | X | |

| BIC | 3233 | 3199 | 3177 | 3206 | 3522 | 3505 |

| MODEL 1 | MODEL 2 | MODEL 3 | MODEL 4 | MODEL 5 | MODEL 6 | |

| COUNTRY SPECIFIC VARIABLES | X | X | X | X | X | |

| RELIGION VARIABLES | X | X | X | X | X | |

| SOCIO-DEMO VARIABLES | X | X | X | X | X | |

| BELIEF VARIABLES | X | X | X | X | X | |

| MARIAGE VARIABLES | X | X | X | X | X | |

| BIC | 3710 | 3676 | 3705 | 3689 | 4177 | 4102 |

Acknowledgements

References

- B. Cassey, and Mulligan. “Galton versus the Human Capital Approach to Inheritance.” Journal of Political Economy 107, no. S6 (1999): S184–S224. [Google Scholar]

- David Landes. “Culture Makes almost all the Difference.” In Culture Matters: How Values Shape Human Progress. Edited by Samuel Phillips Huntington and Lawrence E. Harrison. New York: Basic Books, 2000, pp. 2–13. [Google Scholar]

- Sandra E. Black, Paul J. Devereux, and Kjell G. Salvanes. “Why the Apple Doesn’t Fall Far: Understanding the Intergenerational Transmission of Human Capital.” American Economic Review 95, no. 1 (2005): 437–49. [Google Scholar]

- C. Simon Fan. “Religious Participation and Children’s Education: A social Capital Approach.” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 65, no. 2 (2008): 303–17. [Google Scholar]

- Raquel Fernandez, and Alessandra Fogli. “Culture: An Empirical Investigation of Beliefs, Work and Fertility.” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 1, no. 1 (2009): 146–77. [Google Scholar]

- Jason Long, and Joseph Ferrie. “A Tale of Two Labor Markets: Intergenerational Occupational Mobility in Britain and in the U.S. since 1850.” NBER Discussion Paper, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gary Solon. “Intergenerational Income Mobility in the United States.” American Economic Review 82, no, 3 (1992): 393–408. [Google Scholar]

- Casey B. Mulligan. Parental Priorities and Economic Inequality. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Alberto Bisin, Giorgio Topa, and Thierry Verdier. “Religious Intermarriage and Socialization in the United States.” Journal of Political Economy 112, no. 3 (2004): 615–64. [Google Scholar]

- Shoshana Neuman, and Adrian Ziderman. “How Does Fertility Relate to Religiosity: Survey Evidence from Israel.” Sociology and Social Research 70, no. 2 (1986): 178–80. [Google Scholar]

- Francine D. Blau. “The Fertility of Immigrant Women: Evidence from High Fertility Source Countries.” In Immigration and the Work Force: Economic Consequences for the United States and Source Areas. Edited by George J. Borjas and Richard B. Freeman. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992, pp. 93–133. [Google Scholar]

- Raquel Fernandez, and Alessandra Fogli. “Fertility: The Role of Culture and Family Experience.” The Journal of the European Economic Association 4, no. 2-3 (2006): 552–61. [Google Scholar]

- Shoshana Neuman. “Is Fertility Indeed Related to religiosity.” Population Studies 61, no. 2 (2007): 219–24. [Google Scholar]

- Pablo Brañas-Garza, and Shoshana Neuman. “Parental Religiosity and Daughters’ Fertility: The Case of Catholics in Southern Europe.” Review of the Economics of the Household 5, no. 3 (2007): 305–27. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas Dohmen, Armin Falk, David Huffman, and Uwe Sunde. “The Intergenerational Transmission of Risk and Trust Attitudes.” The Review of Economic Studies 79, no. 2 (2012): 645–77. [Google Scholar]

- Pablo Brañas-Garza, Maximo Rossi, and Dayna Zaclicever. “Individual Religiosity enhances Trust: Latin American evidence for the puzzle.” Journal of Money, Credit & Banking 41, no. 2-3 (2009): 555–66. [Google Scholar]

- Marco Cipriani, Paola Giuliano, and Olivier Jeanne. “Like Mother Like Son? Experimental Evidence on the Transmission of Values from Parents to Children.” IZA Discussion Paper, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rachel M. McCleary, and Robert J. Barro. “Religion and Economy.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 20, no. 2 (2006): 49–72. [Google Scholar]

- Luigi Guiso, Paola Sapienza, and Luigi Zingales. “People's Opium? Religion and Economic Attitudes.” Journal of Monetary Economics 50, no. 1 (2003): 225–82. [Google Scholar]

- Max Weber. The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. London: Allen and Unwin, 1930. [Google Scholar]

- Steve Bruce. “Pluralism and Religious Vitality.” In Religion and Modernization: Sociologists and Historians Debate the Secularization Thesis. Edited by Steve Bruce. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Mark Chaves. “Secularization as Declining Religious Authority.” Social Forces 72, no. 3 (1994): 749–74. [Google Scholar]

- David Yamane. “Secularization on Trial: In Defense of a Neo-Secularization Paradigm.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 36, no. 1 (1997): 109–22. [Google Scholar]

- C. John Sommerville. “Secular Society, Religious Population: Our Tacit Rules for using the Term 'Secularization’.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 37, no. 2 (1998): 249–53. [Google Scholar]

- Ronen Bar-El, Teresa García-Muñoz, Shoshana Neuman, and Yossi Tobol. “The evolution of secularization: cultural transmission, religion and fertility—theory, simulations and evidence.” Journal of Population Economics, 2013. forthcoming. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan R. Wilson. Religion in a Secular Society. London: C. A. Watts & Co., 1966. [Google Scholar]

- David Martin. A General Theory of Secularization. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Olivier Tschannen. “The Secularization Paradigm: A Systematization.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 30, no. 4 (1991): 395–415. [Google Scholar]

- Robert J. Barro, Jason Hwang, and Rachel M. McCleary. “Religious Conversion in 40 Countries.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 49, no. 1 (2010): 15–36. [Google Scholar]

- Mark Chaves, and Philip S. Gorski. “Religious Pluralism and Religious Participation.” Annual Review of Sociology 27 (2001): 261–81. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley Lieberson. “Measuring Population Diversity.” American Sociological Review 34 (1969): 850–62. [Google Scholar]

- David Voas, Daniel V. A. Olson, and Alasdair Crokett. “Religious Pluralism and Participation: Why Previous Research is Wrong.” American Sociological Review 67, no. 2 (2002): 212–30. [Google Scholar]

- Robert J. Barro, and Rachel M. McCleary. “Which Countries Have State Religions? ” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 120, no. 4 (2005): 1331–70. [Google Scholar]

- Mark Chaves, and David E. Cann. “Regulation, Pluralism and Religious Market Structure.” Rationality and Society 4, no. 3 (1992): 272–90. [Google Scholar]

- Oz Shy. “Dynamic Models of Religious Conformity and Conversion: Theory and Calibrations.” European Economic Review 51 (2007): 1127–53. [Google Scholar]

- David B. Barrett, George T. Kurian, and Todd M. Johnson. World Christian Encyclopedia, 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Dean M. Kelley. Why Conservative Churches are Growing: A Study in the Sociology of Religion. New York: Harper & Row, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Wade Clark Roof. “Multiple Religious Switching: A Research Note.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 28, no. 4 (1989): 530–35. [Google Scholar]

- Sharon Sandomirsky, and John Wilson. “Processes of Disaffiliation: Religious Mobility among Men and Women.” Social Forces 68, no. 4 (1990): 1211–29. [Google Scholar]

- Darren E. Sherkat. “Leaving the Faith: Testing Theories of Religious Switching Using Survival Models.” Social Science Research 20 (1991): 171–87. [Google Scholar]

- Matthew T. Loveland. “Religious Switching: Preference Development, Maintenance, and Change.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 42, no. 1 (2003): 147–58. [Google Scholar]

- Pablo Brañas-Garza, and Shoshana Neuman. “Analyzing Religiosity within an Economic Framework: The Case of Spanish Catholics.” Review of Economics of the Household 2, no. 1 (2004): 5–22. [Google Scholar]

- Pablo Brañas-Garza, Teresa García-Muñoz, and Shoshana Neuman. “The Big Carrot: High-Stakes Incentives Revisited.” Journal of Behavioural Decision Making 23, no. 3 (2010): 288–313. [Google Scholar]

- Laurence R. Iannaccone. “The Consequences of Religious Market Structures: Adam Smith and the Economics of Religion.” Rationality and Society 3 (1991): 156–77. [Google Scholar]

- Roger Fink, and Rodney Stark. “Religious Economies and Scared Canopies, Religious Mobilization in American Cities, 1906.” The American Sociological Review 53 (1988): 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Roger Fink, and Laurence R. Iannaccone. “Supply–Side Explanations for Religious Change.” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Sciences 525 (1993): 27–39. [Google Scholar]

- Darren E. Sherkat, and John Wilson. “Preferences, Constraints, and Choices in Religious Markets: An Examination of Religious Switching and Apostasy.” Social Forces 73, no. 3 (1995): 993–1026. [Google Scholar]

- Reginal W. Bibby. “Canada's Mythical Religious Mosaic: Some Census Findings.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 39, no. 2 (2000): 235–39. [Google Scholar]

- Alberto Bisin, and Thierry Verdier. “Beyond the Melting Pot: Cultural Transmission, Marriage, and The Evolution of Ethnic and Religious Traits.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 115, no. 3 (2000): 955–88. [Google Scholar]

- Laurence R. Iannaccone. “Introduction to the Economics of Religion.” Journal of Economic Literature 36, no. 3 (1998): 1465–95. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce Sacerdote, and Edward L. Glaeser. “Education and Religion.” NBER Discussion Paper, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Manfred Te Grotenhuis, and Peer Scheepers. “Churches in Dutch: Causes of Religion Disaffiliation in the Netherlands: 1937-1995.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 40, no. 4 (2001): 591–606. [Google Scholar]

- Evelyn Lehrer. “Religious Intermarriage in the United States: Determinants and Trends.” Social Science Research 27 (1998): 245–63. [Google Scholar]

- David Voas. “Intermarriage and the Demography of Secularization.” British Journal of Sociology 54, no. 1 (2003): 83–108. [Google Scholar]

- 1The literature on secularization is large and extensive. [20,21,22,23,24,25] are some basic references. It covers diverse aspects, such as: (a) differentiation of society's major institutions (law, politics, economy, education, etc.) from religious influence; (b) rationalization [26,27]; (c) demystification of all spheres of life; and (d) less adherence to religious acts, such as attendance of religious services and prayer. See [28] for an inventory of the elements of the classic theories of secularization. Sommerville [24] sorted out the different aspects of secularization and divided them into two categories: those presented in terms of processes (like decline, differentiation, disengagement, rationalization) or in terms of aspects of life or levels of analyses (structural, cultural, organizational, individual).

- 2The terms 'converting out' and 'disaffiliation' will be used (interchangeably) for individuals who were raised in a religion and now define their denomination as 'no religion'. It is obviously an extreme act of secularization.

- 3Religiosity is affected by country-specific aggregates, such as: economic development and political institutions [18]; country religious pluralism and government restrictions on religious conversion [29]. In a study of 40 countries, Barro et al. [29] did not however find significant effects of per-capita GDP, the presence of a state religion and the extent of religiosity on conversion rates.

- 4The sample includes: Australia, Austria, Bulgaria, Canada, Chile, Cyprus, Denmark, France, West Germany, East Germany, Great Britain, Hungary, Japan, Israel, Italy, Ireland, Latvia, New Zealand, Northern Ireland, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Russia, Sweden, Slovenia, Spain, Switzerland, The Czech Republic, The Netherlands, The Philippines, The Slovak Republic and The United States. It appears that the samples of Australia, Cyprus and Israel do not include any respondent who disaffiliated.

- 5Another option was to use fixed-effects regression models. The basic results for the core variables did not change when fixed-effects were used.

- 6Defined as HHI = , the sum of squares of the shares of the country’s religious denominations. It follows that P ranges between 0 (if everyone belongs to the same religion) and (almost) 1 (if there are a large number of religions, each of which covers a negligible fraction of the population). See also [31,32], who refer to the same diversity/pluralism index.

- 7[33] provides a comprehensive country-by-country study on the adoption and abandonment of state-religions over time.

- 8The term 'church' is used as a generic term that relates to the relevant religious place of worship (e.g., also synagogue for Jews, mosque for Moslems, etc.). The religious rules of congregation vary between religions (e.g., many orthodox Jews congregate once or even twice a day, while Christians congregate once a week).

- 9Nevertheless, current age embodies cohort effects: secularization was not common decades ago and has increased in recent years. Assuming that most individuals convert out in their 20s or 30s, because young people are more revolutionary, it follows that older people (e.g., above the age of 60) belong to a cohort of a period when secularization was less common and, therefore, have a lower tendency to disaffiliate.

- 10The ISSP question is: "when you were 12 years old, how often did you attend religious services?" The options are: never (1); once a year (2); one or two times a year (3); a few times a year (4); once a month (5); two or three times a month (6), almost every week (7); every week (8); several times a week (9).

- 11Standard errors at the country level were clustered. The random-effects (RE) model also considers the (ceteris paribus) different behavior of respondents from different countries that stem from the country-specific culture and norms. A RE model seems to be more appropriate than an FE (fixed-effects) model. Moreover, using an FE model does not allow for the inclusion of country-specific variables (that have no within-country variation), such as religious pluralism of the country (P), which are core variables in our study.

- 12The sign of the β estimates relates to the direction of the marginal effects (positive or negative). Based on the estimates of the β coefficients, odd-ratios will be calculated and presented.

- 13Data reported on page 4 refers to current religion (not the one a person is raised in).

- 14For high correlation between GDP and the P-index in the no-Europe subsample, we have removed the first one of the regressions.

- 15Having state-regulation, however, does not affect the tendency to convert out.

- 17These results seem to indicate that consumption motives (churches are places where people can socialize) and professional motives (churches serve as social networks) are not important to individuals who decide to convert out.

- 19See last row in Table 2.

- 20Roof [38], based on GSS 1988, also found that religion switchers tended to be male and well educated. A closely related topic is the relationship between education and religious attendance. It appears that it fluctuates highly among countries: In the United States, church attendance rises with education [50]. Sacerdote and Glaeser [51], who examined 69 countries using the General Social Survey (GSS) 1972–1998, reported that in England and France, they found a positive relationship. However, in most countries, there was no significant relationship between education and religious attendance, whereas in the former socialist countries, the connection was generally strongly negative. Te Grotenhuis and Scheepers [52] and Brañas-Garza and Neuman [42] arrived at insignificant coefficients of schooling in mass participation equations for the Netherlands and Spain, respectively.

- 21What we find is a positive relationship between disaffiliation of the respondent and the affiliation of her/his spouse that has 'no religion'. We do not have information on the date of disaffiliation of the respondent (and his spouse if the spouse is also with 'no religion'), whether it was before or after marriage. It is, therefore, not possible to distinguish between cause and effect: perhaps the subjects converted out when single and, then, naturally, married someone with a 'no religion' affiliation. Regarding marriage effects, see [53].

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Brañas-Garza, P.; García-Muñoz, T.; Neuman, S. Determinants of Disaffiliation: An International Study. Religions 2013, 4, 166-185. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel4010166

Brañas-Garza P, García-Muñoz T, Neuman S. Determinants of Disaffiliation: An International Study. Religions. 2013; 4(1):166-185. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel4010166

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrañas-Garza, Pablo, Teresa García-Muñoz, and Shoshana Neuman. 2013. "Determinants of Disaffiliation: An International Study" Religions 4, no. 1: 166-185. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel4010166

APA StyleBrañas-Garza, P., García-Muñoz, T., & Neuman, S. (2013). Determinants of Disaffiliation: An International Study. Religions, 4(1), 166-185. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel4010166