Psychotherapy with African American Women with Depression: Is it okay to Talk about Their Religious/Spiritual Beliefs?

Abstract

:Introduction

Synthesis of Relevant Literature

African American Women and Major Depressive Disorder

Mental Health Service Use and Quality of Care

African American Women and Use of Religious/Spiritual Coping with MDD

Cultural Competence and Psychotherapy

Role of the Black Church in Addressing Mental Health Issues

Implications for Future Research and Clinical Practice

Research

Clinical Practice

Understanding Conceptualizations of Religion and Spirituality

Self-awareness

Client Assessment

Do Not Make Assumptions

Types of Religious/Spiritual Interventions

Partnership with Clergy

Conclusions

References

- L.W. Cannon, E. Higginbotham, and R.F. Guy. Depression among Women: Exploring the Effects of Race,Class,and Gender. 1989, Memphis, TN, USA: Center for Research on Women,Memphis State University. [Google Scholar]

- E.C. Ward. “Keeping it Real: A grounded theory study of African American clients engaging in counseling at a community mental health agency.” J. Couns. Psych. 52 (2005): 10. [Google Scholar]

- B. Warren. “Depression in African-American women.” J. Psychosoc. Nurs. 32 (1994): 29–33. [Google Scholar]

- L. Cooper, J. Gonzales, J. Gallo, K. Rost, L. Meredith, L. Rubenstein, N. Wang, and D. Ford. “The acceptability of treatment for depression among African- American, Hispanic, and White primary care patients.” Med. Care 41 (2003): 479–489. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- L. Chatters, R. Taylor, J. Jackson, and K. Lincoln. “Religious coping among African Americans, Caribbean Blacks and Non-Hispanic Whites.” J. Community Psychol. 36 (2008): 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- W. Dessio, C. Wade, M. Chao, F. Kronenberg, L.E. Cushman, and D. Kalmuss. “Religion, spirituality, and healthcare choices of African-American women: Results of a national survey.” Ethn. Dis. 14 (2004): 189–197. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- B.C. Post, and N.G. Wade. “Religion and spirituality in psychotherapy: A practice-friendly review of research.” J. Clin. Psychol. 65 (2009): 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- S. Ringel, and J. Park. “Intimate partner violence: Faith-based interventions and implications for practice.” J. Relig. Spiritual Soc. Work 27 (2008): 341–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institue of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. 2001, Washington, DC, USA: National Academy Press.

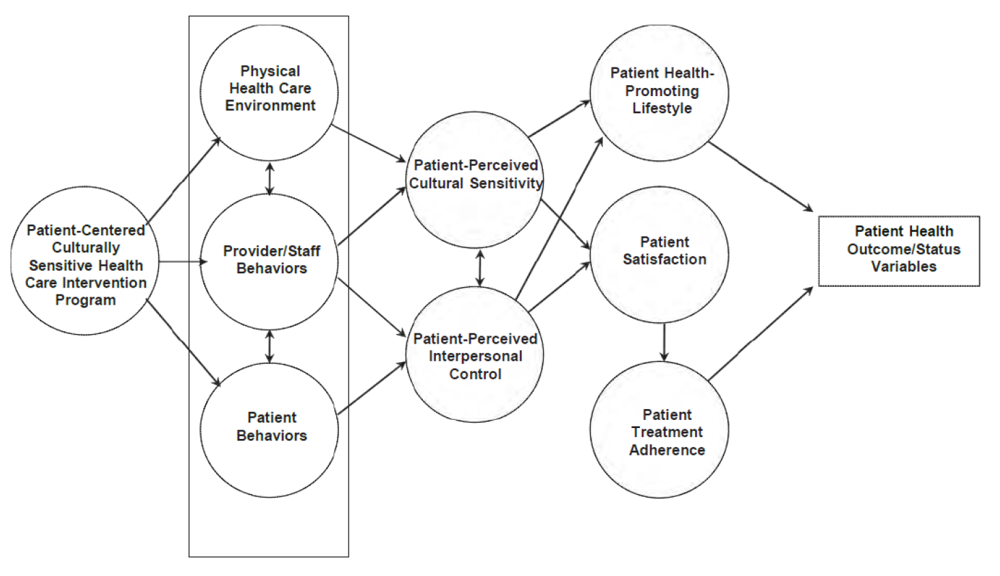

- C.M. Tucker, K.C. Herman, L.A. Ferdinand, T.R. Bailey, M.T. Lopex, and L.L. Cooper. “Providing Patient-Centered Culturally Sensitive Health Care: A Formative Model.” Couns. Psychol. 345 (2007): 679–705. [Google Scholar]

- H. Koenig, M. McCullough, and D. Larson. Handbook of Religion and Health. 2001, New York, NY, USA: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- E.L. Worthington, T.A. Kurusu, M.E. McCollough, and S.J. Sandage. “Empirical research on religion and psychotherapeutic processes and outcomes: A 10-year review and research prospectus.” Psychol. Bull. 119 (1996): 448–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Hage. “A closer look at the role of spirituality in psychology training programs.” Prof. Psych. Resrc. Pract. 37 (2006): 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- I.S. Richards. ,Bergin,A.E. A Spiritual Strategy for Counseling and Psychotherapy. 2005, Washington, DC, USA: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- B. Zinnbauer, K. Pargament, and A.B. Scott. “The Emerging Meanings of Religiousness and Spirituality: Problems and Prospects.” J. Pers. 67 (1999): 889–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R.J. Taylor, L.M. Chatters, and J. Levin. Religion in the Lives of African Americans: Social,Psychological and Health Perspectives. 2004, Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: Sage Press. [Google Scholar]

- N. Krause, and L.M. Chatters. “Exploring race differences in a multidimenstional battery of prayer measures among older adults.” Soc. Rel. 66 (2005): 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R.J. Taylor, L.M. Chatters, R. Jayakody, and J.S. Levin. “Black and white differences in religious participation: A multi-sample comparison.” J. Sci. Stud. Relg. 35 (1996): 403–410. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. Diagnostic and sTatistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV-TR. 2000, Arlington, VA, USA: American Psychiatric Publishing Inc.

- M.M. Weissman, and M. Olfson. “Depression in women: Implications for health care research.” Science 269 (1995): 799–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- “National Institue of Mental Health. Transforming the understanding and treament of mental illness through research.” Available online: http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/women-and-depression-discovering-hope/complete-index.sht (accessed on 12 December 2011).

- D. Chapman, and G. Perry. “Depression is a major component of public health for older adults.” Prev. Chronic Dis. 5 (2008): 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- C. Mathers, and D. Loncar. “Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030.” PLoS Med. 3 (2006): 2011–2030. [Google Scholar]

- D.R. Williams, H. Gonzalez, H. Neighbors, R. Nesse, J.M. Abelson, J. Sweetman, and J.S. Jackson. “Prevalence and distribution of major depressive disorder in African Americans, Caribbean Blacks, and Non-Hispanic Whites: Results for the national survey of American life.” Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 64 (2007): 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R.C. Kessler, K.A. McGonagle, S. Zhao, C.B. Nelson, M. Hughes, S. Eshleman, H. Wittchen, and K.S. Kendler. “Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States.” Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 51 (1994): 8–19. [Google Scholar]

- F.M. Culbertson. “Depression and gender: An international review Am. ” Psychol. 52 (1997): 25–31. [Google Scholar]

- E. McGrath, G. Keita, P. Gwendolyn, B. Strickland, and N. Russo. Women and Depression: Risk Factors and Treatment Issues: Final Report of the American Psychological Association's National Task Force on Women and Depression. 1990, Washington, DC, USA: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- C.J.L. Murray. “Global Burden of Disease.” 2000. Available online: http://www.who.int/evidence/bod (accessed on 30 June 2011),Global Program on Evidence for Health Policy Discussion Paper No. 50.

- E. McGrath, G. Keita, B. Strickland, and N. Russo. National Depression Summit. 2001, Washington, DC, USA: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- L.P. Kohn, and K.M. Hudson. “Gender, ethnicity, and depression: Intersectionality and context in mental health research with African American women.” Afr. Am. Resrch. Perspect. 8 (2002): 174–184. [Google Scholar]

- C.B.W.H. Project. “Healing for the mind,body,and soul: new notes from California Black women's health project.” Available online: http://www.cabwhp.org./pdf/Surveyreport.pdf (accessed on 30 May 2011).

- E.L. Barbee. “African American women and depression: A review and critique of the literature.” Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 6 (1992): 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- E.C. Ward, L.O. Clark, and S. Heidrich. “African American Women's Beliefs, coping behaviors, and barriers to seeking mental health services.” Qual. Health Res. 19 (2009): 1589–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U. S. Department of Health and Human Services. Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity. A Supplemental of Mental Health. 2001, Rockville, MD, USA: A Report of the Surgeon General.

- B. Sanders, and M. Akbar. “African Americans’ Perceptions of Psychotherapy and Psychotherapists.” Prof. Psych. Resrc. Pract. 35 (2004): 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- F.K. Cheung, and L.R. Snowden. “Community mental health and ethnic minority populations.” Community Ment. Health J. 26 (1990): 277–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- J. Gallo, S. Marino, D. Ford, and J. Anthony. “Filters on the pathway to mental health care, II: Sociodemographic factors.” Psychol. Med. 25 (1995): 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A.L. Whaley, and P.A. Geller. “Toward a cognitive process model of ethnic/racial biases in clinical judgement.” Rev. Gen. Psych. 11 (1997): 75–96. [Google Scholar]

- T. LaVeist, and T. Carroll. “Race of physician and satisfaction with care among African-American patients.” J. Am. Med. Assoc. 94 (2002): 937–943. [Google Scholar]

- C. Bell, and J. Mattis. “The importance of cultural competence in ministering to African American victims of domestic violence.” Viol. Against Wom. 6 (2000): 515–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Bourjolly. “Differences in religiousness among black and white women with breast cancer.” Soc. Work Health Care 28 (1998): 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- M. Constantine, E. Lewis, L. Conner, and D. Sanchez. “Addressing spiritual and religious issues in counseling African Americans: Implications for counselor traning and practice.” Couns. Values 45 (2000): 10. [Google Scholar]

- M. Tully. Lifting Our Voices: African American Cultural Responses to Trauma and Loss. Honoring Differences: Cultural Issues in the Treatment of Trauma and Loss. 1999, Philadelphia, PA, USA: Brunner/Mazel. [Google Scholar]

- P. Van. “Breaking the silence of African-American women: Healing after pregnancy loss.” Health Care Women Int. 22 (2001): 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D. Brome, M. Owens, K. Allen, and T. Vevaina. “An examination of spirituality among African American women in recovery from substance abuse.” J. Black Psychol. 26 (2000): 470–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L.C. Smith, S. Friedman, and J. Nevid. “Clinical and sociocultural differences in African Ameican and European American patients with panic disorder and agoraphobia.” JNMD 187 (1999): 549–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. Neighbors, M. Musick, and D. Williams. “The African American minister as a source of help for serious personal crises: bridge or barrier to mental health care? Health Educ. ” Behav. 25 (1998): 759–777. [Google Scholar]

- J. Queener, and J. Martin. “Providing culturally relevent mental health services: Collaboration between psychology an the African American church.” J. Black Psychol. 27 (2001): 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. Pollack, S. Harvin, and R. Cramer. “Coping resources of African American and White patients hospitilized for bipolar disorder.” Psychiatr. Serv. 51 (2000): 1310–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D.R. Brown, and L.E. Gary. “Social support network differentials among married and nonmarried Black females.” Psych. Women Quart. 9 (1985): 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D.R. Brown, and L.E. Gary. “Religous involvement and health status among African-American males.” J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 86 (1994): 825–831. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- D. Brown, F. Ahmed, L.E. Gary, and N.G. Milburn. “Major depresion in a community sample of African Americans.” Am. J. Psychiatr. 152 (1995): 373–378. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- A.T. Woodward, K.M. Bullard, R.J. Taylor, L.M. Chatters, R.E. Baser, and B. Perron. “Use of Complementary and Alerternative Medicine for Mental Disorders Among African Americans, Black Caribbeans, and Whites.” Psychiatr. Serv. 60 (2009): 1342–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- L. Chatters, J. Mattis, A.T. Woodward, R.J. Taylor, H.W. Neighbors, and N.A. Grayman. “Use of Ministers for a Serious Personal Problem Among African Americans: Findings from the National Survey of American Life.” Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 81 (2011): 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D.R. Brown, S.C. Ndubuisi, and L. Gary. “Religiousity and psychological distress among blacks.” J. Rel. Health 29 (1990): 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. Boyd-Franklin, and T. Lockwood. Spirituality and Religion: Implications for Psychotherapy with African American Clients and Families. 1999, p. 13. New York: NY, USA: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- W. Myers. “Integrating spirituality into counselor preparation: A developmental, wellness approach.” Couns. Values 47 (2003): 142–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Young, C. Cashwell, M. Wiggins-Frame, and C. Belaire. “Spiritual and religious competencies: A national survey of CACREP-accrediated programs.” Couns. Values 47 (2002): 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Cashwell, and J. Young. “Spirituality in counselor trainning: A content analysis of syllabi from introductory spirituality courses.” Couns. Values 48 (2004): 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L.D. Furman, and E.R. Canada. Spiritual Diversity in Social Work Practice. 1999, New York, NY, USA: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- M. Asher. Spirituality and religion in social work practice. Available online: www.gatherthepeople.org/Downloads/SPIRIT_IN_SW.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2011).

- K. Pargament, and B. Zinnbauer. “Working with the sacred: Four approaches to religious and spiritual issues in counseling.” J. Couns. Dev. 78 (2000): 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. Lindsay, and G. Gallup. Surveying the Religious Landscape: Trends in U.S. Beliefs. 1999, Harrisburg, PA, USA: Morehouse Publisher. [Google Scholar]

- J.C. Fox, and M. Blank. “Guterbock Alternative Mental Health Services: The role of the Black Church in the South.” Am. J. Public Health 92 (2002): 1668–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R.E. Meyer. Black History and the Historical Profession,1915–1980. 1986, Urbana, IL, USA: University of Illinois Press. [Google Scholar]

- N. Foner. “Race and color: Jamaican migrants in London and New York City.” Forced Migr. Rev. 19 (1985): 708–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W.E.B. Du Bois. The Negro Church in America. 1903, Atlanta, GA, USA: Atlanta University Press. [Google Scholar]

- G. Foluke. The Old-time Religion: A Holistic Challenge to the Black Church. 1999, New York, NY, USA: Winston-Derek. [Google Scholar]

- C. Sutton. Pass it on: Outreach to Minority Communities. 1992, Philadelphia, PA, USA: Big Brothers/Big Sisters of America. [Google Scholar]

- A. Abdul. Religion and the Black Church: Introduction to Afro-American Studies. 1991, Chicago, IL, USA: Twenty-First Century Books. [Google Scholar]

- L.H. Mamiya, and C.E. Lincoln. The Black Church in the African American Experience. 1990, Durham, NC, USA: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- R. Anderson, T. Nakazono, P. Davidson, and W.E. Cunningham. “Do Black and White adults use the same sources of information about Aids prevention.” Health Educ. Behav. 26 (1999): 703–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- L. Perez, H.G. Koenig, and K.I. Pargament. “The many methods of religious coping: Development and initial validation of the RCOPE.” J. Clin. Psychol. 56 (2000): 519–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- C.L. Park, and R. Paloutzian. tegrative Themes in the Current Science of the Psychology of Religion. In Handbook of the Psychology or Religion and Spirituality. 2005, New York, NY, USA: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- P.C. Hill, and K.I. Pargament. The Psychology of Religion and Coping. 2003, New York, NY, USA: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- M.T. Burke. From the chair. The Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP) Connection Winter 1998.

- M.I. Wiggins. “Therapist self-awareness of spirituality. ” In Spirituality and the Theraputic Process. Edited by J.D.A.M.M. Leach Ed. 2008, Washington, DA, USA: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- N.G. Wade, and B.C. Post. “Religion and Spirituality in Psychotherapy: A Practice-Friendly Review of Research.” J. Clinical Psych. 65 (2007): 131–146. [Google Scholar]

- D. Burdzy, M. Feuille, and K.I. Pargament. “The brief RCOPE: Current psychometric status of a short measure of religious coping.” Religions 2 (2011): 51–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N.G. Wade, J.A. Hayes, and C.V. Johnson. “Psychotherapy with troubles spirits: A qualitative investigation.” Psych. Resrch. 17 (2007): 1450–1460. [Google Scholar]

- E.L. Worthington. “Religious counseling: A review of published empirical research.” J. Couns. Dev. 64 (1986): 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Collins, and E.C. Ward. “Depression in African American males.” Perspectives (Montclair), 2010, 6–21. [Google Scholar]

© 2012 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Mengesha, M.; Ward, E.C. Psychotherapy with African American Women with Depression: Is it okay to Talk about Their Religious/Spiritual Beliefs? Religions 2012, 3, 19-36. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel3010019

Mengesha M, Ward EC. Psychotherapy with African American Women with Depression: Is it okay to Talk about Their Religious/Spiritual Beliefs? Religions. 2012; 3(1):19-36. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel3010019

Chicago/Turabian StyleMengesha, Maigenete, and Earlise C. Ward. 2012. "Psychotherapy with African American Women with Depression: Is it okay to Talk about Their Religious/Spiritual Beliefs?" Religions 3, no. 1: 19-36. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel3010019

APA StyleMengesha, M., & Ward, E. C. (2012). Psychotherapy with African American Women with Depression: Is it okay to Talk about Their Religious/Spiritual Beliefs? Religions, 3(1), 19-36. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel3010019