Abstract

Konrad Wolf was one of the most enigmatic intellectuals of East Germany. The son of the Jewish Communist playwright Friedrich Wolf and the brother of Markus Wolf—the head of the GDR’s Foreign Intelligence Agency—Konrad Wolf was exiled in Moscow during the Nazi era and returned to Germany as a Red Army soldier by the end of World War Two. This article examines Wolf’s 1968 autobiographical film I was Nineteen (Ich war Neunzehn), which narrates the final days of World War II—and the initial formation of postwar reality—from the point of view of an exiled German volunteer in the Soviet Army. In analyzing Wolf’s portrayals of the German landscape, I argue that he used the audio-visual clichés of Heimat-symbolism in order to undermine the sense of a homogenous and apolitical community commonly associated with this concept. Thrown out of their original contexts, his displaced Heimat images negotiate a sense of a heterogeneous community, which assumes multi-layered identities and highlights the shared ideology rather than the shared origins of the members of the national community. Reading Wolf from this perspective places him within a tradition of innovative Jewish intellectuals who turned Jewish sensibilities into a major part of modern German mainstream culture.

1. Introduction

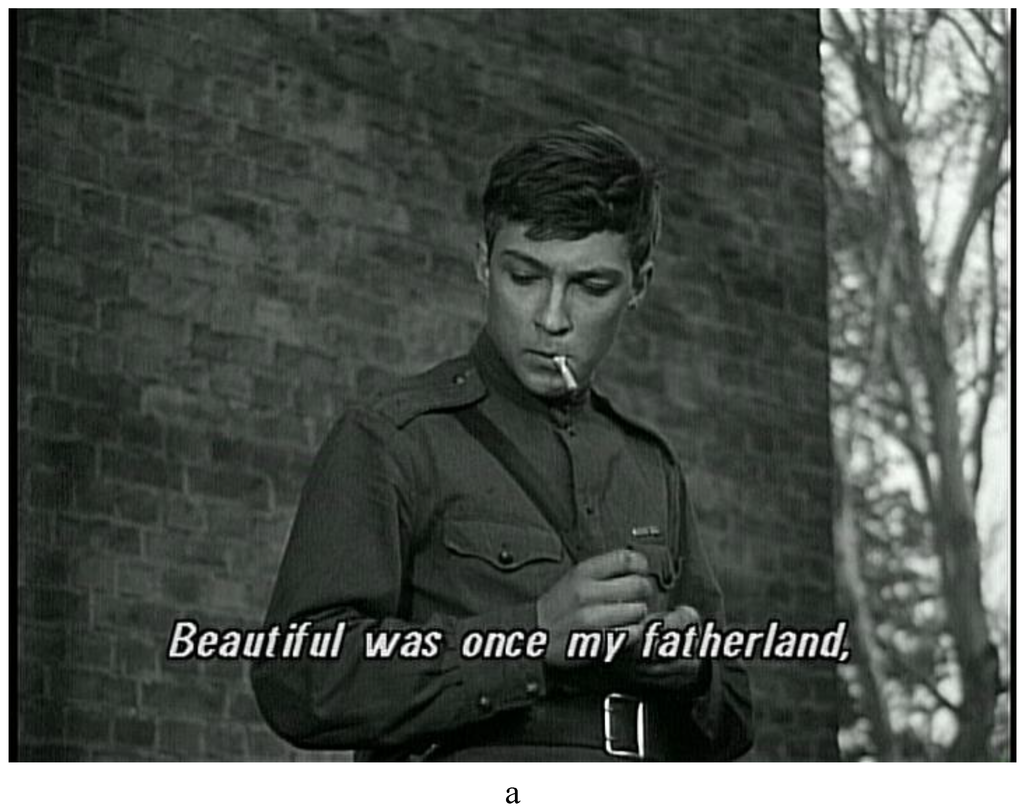

At first glance, Konrad Wolf’s 1968 film I was Nineteen (Ich war Neunzehn) is a story of a triumphant homecoming. The protagonist Gregor Hecker, a Communist German-Jew, returns from exile together with the marching Red Army on its way toward Berlin in the spring of 1945 (Figure 1a). Serving as a translator, he seems to personify a bridge between German and Russian nationalities, a link between the invading Soviets and the local—political, psychological and natural—landscape. The film begins, accordingly, with an ostensibly serene reunion between the protagonist and his homeland, which he left behind when the Nazis took power. Together with him, viewers are offered a panoramic view of the scenery, a wide river flows peacefully in the fog, with solemn hill slopes emerging in the background and small rafts crossing leisurely (Figure 1b).

This scenic view blends different themes and emphases. It combines the historical realism of the Soviet military campaign, the universal, psychological drama of an émigré’s return to his place of birth, and the conventional imagery of German Heimat culture. The utilization of such imagery indicates that Hecker is not merely marching into a defeated state, but is rather returning to his Heimat, namely, to the “authentic” national landscape, undistracted by the annihilating forces of modernization and war. At first glance, the Heimat paradigm appears to reconcile the tensions between the universal and individual-psychological aspects of the scene. The protagonist’s homecoming fits well within the generic narrative of Heimat culture (in particular in the aftermath of World War II), in which, conventionally, the rediscovered landscape and way of life of the community reminds the protagonist that—notwithstanding the reasons for his departure and his experiences during his journeys—there is “no place like home” [1]. Shortly thereafter, however, I was Nineteen deviates from the familiar formula, as Gregor Hecker’s voice shatters the idyllic image of the German landscape and places it within a reality of violence, alienation and despair: “the war is lost,” he announces in German through the loudspeakers to the Wehrmacht soldiers on the other side of the river, “and you are in a hopeless position” (Figure 1c).

Figure 1.

a. Gregor Hecker, the protagonist of Konrad Wolf’s I was Nineteen. b. Opening sequence: the first encounter of the prodigal son with the homeland. c. The Heimat as a sphere of violence and despair.

The incongruence of the peaceful scenery and the true nature of the scene—suggested by the repeated sentence emanating from the unseen loudspeakers—constitutes the former, generic Heimat imagery as a mere deception. This sense of deception is a cardinal element in the early films of Konrad Wolf (1925–1982), one of the most prominent East-German film-makers. It provides the framework within which Wolf formulated his cinematic reflections about the recent German past and the reconstitution of German nationalism after the National Socialist catastrophe. Based on a close reading of I was Nineteen, this article underscores the ways in which Wolf phrased his criticism of the formation of postwar German identity in the GDR through manipulation of Heimat symbolism. In undermining the generic imagery associated with the concept of Heimat (especially since 1933, when the perception of Heimat as a concept revolving “around the central themes of race, blood and German destiny” was standardized under Nazi rule [2]), Wolf sought to override the notion of collective identity it entailed: namely, that of a homogeneous community molded by its “authentic” attachment to the national landscape. Perceived in this manner, the concept of Heimat symbolized Wolf’s incorrigible otherness as a German Jew. His portrayal of the final days of Nazi Germany, therefore, is formulated as a struggle against the attempt to view the local landscape as a metaphor for a German nationality that predetermines his otherness.

Since the late nineteenth century, and particularly in the aftermath of the World Wars, Heimat iconography offered a unique linkage between the regional landscapes and shared national characteristics, providing symbolism in which the familiar local landscape functioned as a metaphor for the abstract qualities of the nation [3,4,5]. Drawing on this tradition, Wolf described his works as an ongoing search for a Heimat, for a place in which he—through his protagonists—would feel “at home”; the place which would connect him with “his people” [6]. The discussion below suggests, however, that Wolf’s quest for a genuine Heimat undermined the mythic powers of this imagery and portrayed it as a destructive illusion. Wolf’s exploitation of the Heimat metaphor in search of a new German identity reveals a distinctive endeavor to face the challenge of the problematic German-Jewish “symbiosis” in post-Holocaust East-Germany. Blending irony and optimism, Wolf offered his viewers a vision of a community based on shared values and experiences rather than on inborn characteristics. His critique of the Heimat ideal, and his position as an “outsider within,” was nonetheless rooted in the political paradigms of the Cold War. A sober supporter of German socialism, Wolf did not believe that the socialist credo alone would solve the ‘Jewish problem’; he rather interpreted Socialism as a distinctive, critical viewpoint, according to which guidelines for a new path in German (and German-Jewish) history could be marked.

2. German-Jewish Dialog in the East-German Heimat

At the core of Heimat symbolism lie the contours and characteristics of the national community, its formation and its manifestations, and the changes in the political and social reality over time [7]. Postcards, poems, political addresses and films, have portrayed the environment of the Heimat and the relationships between the members of its community as the essential influence on the formation of individual identity within this sphere [8,9]. In his survey of pre-1918 Heimat iconography, Alon Confino, found that it served a dual objective: to indicate the (metaphorical) uniformity of “the local, regional, and national way of life,” and to depict “the nation as a community within nature and in harmony with nature” [10]. It therefore incorporated “generic” landmarks, such as inconspicuous brooks, hills, and trees, alongside human-made objects, such as (unidentified) church towers. As recent scholarship has noted, contrary to a commonly held belief, Heimat imagery has never manifested a merely reactionary (and nationalist) longing for pre-modern harmony, but rather reflected an attempt to reconcile tensions that characterize times of fundamental social, cultural and political transformation [11,12,13]. This iconography, however, gained additional connotations in the aftermath of World War One and during the Nazi period. The notion of Heimat enabled the imagination of the nation as being detached from the war defeat, from the state’s deep political crisis, and from the ‘foreign’ elements within modern German society. Within the then popular terminology of Ferdinand Tönnis’ paradigms [14], Heimat enabled modern society in Germany to imagine itself as a German national community.

The history of the utilization of Heimat symbolism in German film begins in the early years of German cinema. Considered to be the only “genuine German genre,” Heimatfilm contemplated the perennial conflicts of German society by combining a highly modernized technology of representation with iconic imagery of pre-modern, or ostensibly timeless, landscape [15,16,17]. Scholarly discussion of West-German Heimatfilm often refers to its immense popularity during the years of restoration under Adenauer’s conservative regime, when the general mood was consistent with the genre’s emphasis on nation-building and reconciliation of social tensions [18]. According to this interpretation, the panoramic images of a de-politicized landscape, detached from recent catastrophes, served a need both for escapism and nation-building in the years that followed the immense destruction and loss of the war.

Scholars have, until recently, tended to disregard the important role played by Heimat imagery, and Heimatfilm in particular, in the nation-building process and the establishment of national ideology in the GDR [19]. However, the current interest in the productions of DEFA (Deutsche Film Aktien-Gesellschaft, the East German national studios)—which underlines the role of genre films and transnational influences—facilitates a better informed discussion of the East German Heimatfilm of the 1950s and its socio-political roles [20]. It was, for instance, noted that films such as Martin Hellberg’s Das verurteilte Dorf (The Condemned Village, 1952) and Der Ochse von Kulm (The Ox from Kulm, 1955) effectively mobilized Heimat imagery to serve the ideology of the SED. These films exploited the sentiments evoked by this imagery in modern German popular culture in order to reflect on the role of the GDR as the defender of “genuine” German attributes under threat from the capitalist superpower [21].

Heimatfilm’s conventions are abundant in Konrad Wolf’s films, in particular in the early years of his career. His debut as a film director, Einmal ist Keinmal (One Time is no Time, 1955), is a musical fairytale that incorporates various elements of the Heimatfilm genre. Utilizing scenery and soundtrack that echoed the traditional Heimat culture, Wolf’s narrative—a love story involving a local girl and a visitor from West Germany—underlines the reconciliation of ideological tensions through the metaphor of harmonious integration of different musical traditions. When viewed alongside other contemporaneous East-German productions, however, it becomes apparent that several features of this film distance it from the political outlines of other Heimat-films made by DEFA: e.g., the ironic dialogues, the blend of realism and mystic components, and the airing of the distinctive point of view of a stranger, a visitor, throughout the film [22]. Wolf’s fascination with Heimatfilm’s conventional imagery is apparent in several later films, albeit in more implicit manner. Most notably, in films that portrayed the recent German history—such as Sterne (Stars, 1959) and Sonnensucher (Sun Seekers, 1958)—he recurrently displayed panoramic vista of Heimat-style landscape. With the transition to more concrete political circumstances, however, the lightheaded contemplations presented in the magical forest of One Time is no Time were replaced by a sense of urgency and gravity. This trend reaches its climax in Wolf’s 1968 I was Nineteen. Here, reflecting on the Soviet occupation and on the East-Germans’ ability to overcome the trauma of the war, Wolf presents Heimat imagery as an uncanny interference, unrelated to and yet underlining the horrors of the real world. Staged as a journey in a displaced Heimat, I was Nineteen underscores the dissociation between the imaginary Heimat and home. As I argue below, the film is a desperate attempt to restore the notion of a German community through the annihilation of the ideas and sentiments associated with Heimat. Eventually he calls for a new type of community that would encourage the assimilation of the social elements that could not participate in the Heimat ideal; a new German-Jewish symbiosis, that is.

In his widely cited and harsh criticism of the notion of “German-Jewish symbiosis,” Gershom Scholem asserted that such a concept was dangerously misleading, since there had never been a genuine dialog between Germans and Jews in the pre-Nazi era. Jews, he maintained, could venture into the German national discourse—could be a part of, and influence, German identity—only as individuals who endeavored to efface the differences between them and their German ‘hosts,’ not “as Jews,” [23,24]. Current scholars have criticized the “wrong and a-historical” notion of authentic and recognizably different Jewish and German cultural identities embedded in Scholem’s terminology [25,26,27]. The emphasis has therefore shifted to the experiences and perceptions of the German-Jewish “symbiosis.” Jack Zipes, for instance, depicted the German-Jewish intellectual experience in terms of a “failed” symbiosis, a phenomenon to which Jews aspired and depicted as a necessity, while at the same time acknowledging its impossibility and its ‘destructive’ potential [28]. Dan Diner’s oft-cited reflection on the “negative” symbiosis locates it in post-World War II West Germany, where the presence of Jews generated a sense of “contradictory mutuality” that places Auschwitz as a major point of reference for both Jewish and German identities, and enabled the formation of post-Holocaust German nationalism (or the “reidentification of Germans with Germany”) [29]. According to this argument, postwar West-German Jews have had an important role, qua Jews, in the German discourse of national identity, but did not, nor could they, participate in this discourse.

Scholars of the German Democratic Republic tend to portray the German-Jewish dialog in East-Germany in a way that recalls Scholem’s depiction of the pre-1933 lack of symbiosis—i.e., integration into the discourse as individuals, not as Jews—rather than Diner’s portrayal of the West-German pattern. Even though since the mid-1950s the GDR—like its Western counterpart—tolerated the activity of the Jewish community, funded it, and incorporated it into the post-Nazi national ethos, scholars commonly note that the Jews who rose to prominence in the cultural arena were not part of the Jewish community and have not identified themselves with its traditions and practices [30,31]. “Staunchly refus[ing] to consider themselves Jews,” as one scholar remarked, these intellectuals and artists often regarded their Jewish ancestry as something related merely to religious conviction, and hence irrelevant to their German identity in the atheist-socialist GDR. Allegedly, like the Jews mentioned by Scholem, they became an important element of German national discourse only once they had marginalized their Jewish identity [33].

At first glance, Konrad Wolf seems to fit well within these parameters. The son of the famous Communist physician and playwright Friedrich Wolf, and the brother of Markus Wolf, the head of the GDR foreign intelligence (Hauptverwaltung Aufklärung), Wolf was undeniably one of the most prominent and influential film-makers of the GDR, who received local and international recognition as a representative of the emerging culture of his state. Similar to several other prominent artists and intellectuals of Jewish ancestry, Wolf was not a practicing Jew and his films hardly include any explicit identification with Judaism or with the Jewish people. A closer look at his films, however, reveals a more nuanced, multifaceted approach to the German-Jewish question, which deviates from a mere refusal to be identified as a Jew.

Wolf’s life and works have underscored a variety of seemingly insoluble tensions caused by different perceptions of identity. Exiled in Moscow with his family since 1933, the youthful Wolf enthusiastically embraced Russian Communism, served in the Soviet military, and returned to Moscow after the war to complete his training as a film-maker. Here, he could hardly overlook the widespread anti-Semitic sentiments in the Moscow of the late Stalinist era [34]. Notably, Wolf’s experiences as a conspicuous outsider during these years—both in Germany (as a Jew and as a soldier in the Red Army) and in Moscow (as a Jew and as a German)—did not drive him to the cultural margins of East-Germany [35,36]. His work, rather, incorporated his constant sense of alienation into the GDR’s mainstream national culture. While Western critics associated him with the genius and the rebellious spirit of contemporaneous “New Wave” film-makers [37], the political leadership of the East-German state embraced him and appointed him head of the National Academy of Arts (a position he held from 1965 until his death in 1982). A member of the Central Committee of the governing Socialist Union Party (SED), Wolf declared that his entire filmography was facilitated by and dedicated to the ideas and values espoused by the party [38,39]. Nevertheless, despite the recognition accorded to his work by the state, his films were recurrently criticized by representatives of the SED and its suppoters for their “non-persuasive,” or “superficial” ideological content [40]. In some cases, the ‘vagueness’ of his messages appeared to threaten the party’s objectives; his film Sonnensucher (Sun Seekers, 1958) was banned for thirteen years before it was allowed to be screened. The ambivalence that caracterized his career, his immanent role as both insider and outsider to the socialist state, appears to correspond with his perception of German national identity and his place therein. Indeed, the grater part of his filmogrpahy focuses on rebellious individuals who seek to belong to the community without relinquishing their peculiarities; men and women who aspire to be insiders as outsiders (e.g., in Der geteilte Himmel, Divided Heaven, 1963; Solo Sunny, 1978; and Goya, 1971) [41].

3. I was Nineteen: A Homeland without a Home

To a large extent an autobiographical film, I was Nineteen narrates the final days of World War II from the point of view of Gregor Hecker, who—like Konrad Wolf—left Germany for the Soviet Union when he was eight, after the Nazis took power, and returned to his homeland as a nineteen year old soldier in the Red Army. Gregor’s journey toward Berlin, into the German heart of darkness, occurs at a unique historical moment, namely, once the collapse of the National-Socialist State has become inevitable and before a new regime, a new national ideology, and a new notion of German identity have been established. Condensed to just a few hours that cover the end of World War II and the initial inkling of the Cold War, the events in the film also occur in a metaphorical realm, in which various perceptions of the German past and future are confronted. As he becomes re-acquainted with the German landscape, Gregor encounters a variety of German “types,” such as a small town bourgeois couple; a member of the pre-1933 communist party; a wounded blind soldier; a still devoted SS officer, and an opportunist SS officer who exploits his privileges in order to survive the war; a contemplative intellectual; and an anxious, helpless family of farmers. These encounters repeatedly engender discussions about the “meaning” of Germany’s recent history and about the ‘essence’ and the prospects of the national community. In the final scene Gregor joins forces with some deserting Wehrmacht soldiers against their common enemy, the still loyal SS units. At the end of this chain of events, which marks the end of the film, Konrad Wolf declares—this time in his own voice—“I am German.” Set in a lone farmhouse by a small stream, surrounded by trees, fields and hills, the depiction of this new alliance appears to suggest that Gregor has found—or rediscovered—his genuine community in “his” Heimat. The rediscovery of the German Heimat seems to match scholars’ reading of I was Nineteen as a cornerstone of DEFA’s antifascist film, which “allowed filmmakers to remap the affective landscape of antifascism, reassess its historical status, and reaffirm its meaning for the present” [42].

This impression, I argue, is wrong; I was Nineteen is a film about the deception and the danger embedded in the notion of Heimat, and represents an attempt to undermine its enduring hold on the national imagination. At the beginning of the film, after the crossing of the river mentioned above, Georg is back in his land of birth. The return of the protagonist to the German landscape is a narrative framework that resonates with that of the conventional Heimatfilm (including Wolf’s One Time is no Time): an outsider arrives at the Heimat and eventually discovers that he belongs there; that he has come home. Yet, as in the unfolding of the opening scene, I was Nineteen sets up this framework in order to subvert its premise. Throughout the film Gregor seems to be devoid of Heimatgefühl, namely, of the emotional link to the place and the community to which one belongs; or, simply, of the feeling of “being at home” [43,44]. Wolf employs two main methods to confer this lack of Heimatgefühl. First, while set in “German” territory, the film consists primarily of movement and transitions of the scenery. Rather than being-in the landscape, Gregor relentlessly drives from one place to another together with his unit. One is shown no maps or given any strategic reasoning for the movement throughout the film. Depicted from Gregor’s point of view, that of an uninformed ordinary soldier, his constant motion appears arbitrary, if not irrational. Like many of his fellow soldiers, Gregor is mostly confused about his whereabouts. His disorientation in the Heimat is compounded by the ostensibly arbitrary pauses in the journey. While the reason for some of these pauses is explained—e.g., the wish to prevent unnecessary bloodshed by convincing some German soldiers to surrender—most of the halts seem to occur at random (to the viewers and apparently to Gregor): e.g., in the home of a German intellectual; in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp; or in a riverside garden, where a man suspected of collaborating with the Nazis is captured and executed by another unit.

Gregor’s inability to feel at home in the Heimat is underlined when he is appointed by his officer – again, in a seemingly arbitrary fashion—to the post of governor of a small German town. In this capacity he meets a young local woman, who craves his affection (and protection). The anticipated romantic union between the returning exile and representative of the young German generation appears at first to be a metaphor for a new potential union of different elements of post-war German society. Shortly thereafter, however—and as abruptly as he was appointed—Gregor is ordered to leave the town and moves on. His emphatic-yet-unconcerned approach toward the fate of the woman he leaves behind further accentuates his lack of emotional attachment to the land and its inhabitants. A similar indifference is exhibited during his encounter with an injured Wehrmacht soldier, when his vehicle momentarily comes to a halt on a small bridge. Gregor engages in conversation with the blinded soldier, speaking German in a way that emphasizes their belonging to the same nationality. Their camaraderie, nonetheless, is based on a lie. The blind German fails to notice—or pretends to be oblivious to the fact—that Gregor is part of the enemy’s military (their dialog focuses on the question of where is Gregor “from,” i.e., from which region in Germany). This false camaraderie is short-lived and Gregor soon moves on, unfeelingly leaving the man to die there.

I was Nineteen is thus a film about moving through the land, rather than about returning to and residing in the place where the protagonist “belongs.” The abovementioned small town episode also serves to demonstrate the second method Wolf employs to undermine the expectations associated with the conventional tale of homecoming, namely, his apparent discomfort in actual German homes. When Gregor visits homes during the film, such as the apartment he confiscates for his office as local governor, he restlessly moves around in them, seldom sitting still. His behavior indoors oscillates between irritation and lack of confidence; even though he ‘owns’ the house, since his bedroom is also his office he is devoid of genuine privacy, a foundational element of the feeling of being at home. His inability to feel at home in Germany is underscored on a visit to the home of a “typical” German intellectual, who contemplates the origins of Nazism with the young Soviet officers in his library. Gregor refuses both to sit comfortably in the living room and to engage in conversation about German culture. His sense of unease with regard to the German home is manifested in his lack of interest in the particularities of the German cultural heritage. He cares little for the ‘German psyche’ (as revealed in the national culture) and has little patience for German music (contrary to other Red Army officers who are eager to listen to German music and to discuss its merit). Unlike his curious Russian fellows, his body language expresses agitation. He longs to be out of there.

Notably, Gregor’s inability to feel at home is matched by his apparent inability to articulate the Jewish dimension of his identity. During his various encounters with Germans, he is repeatedly asked whether he is Jewish (some, like the conniving SS adjutant he meets in Spandau, ask directly; others, like the blind soldier, inquire indirectly about his family business in Köln). Gregor responds to these inquiries with a silent—at times almost embarrassed—gaze. Only once in the film does he reveal his emotions (or at least his confusion) regarding his ties with the Jewish people. This dramatic (and brief) display of emotion takes place at a rare moment in the film, when it abruptly deviates from Gregor’s point of view and turns to a visit by Soviet generals in the now-deserted Sachsenhausen concentration camp. The generals listen to an explanation of the camp’s methods of extermination by a former operator of the local machinery. This powerful sequence cuts between the didactic exploration of the Nazi killing machine and the wet face of Gregor, who is taking a shower in an unspecified location. As he covers his eyes with a towel, Gregor’s rage and helplessness appear to be a direct response to the murder of Jews (which is immediately contrasted by the somber and objectively detached faces of the generals in the camp). In the following shot, the generals ask the operator about the identity of the victims of the camp, to which the latter replies with the politically correct answer: “mostly Russians.” When the camera cuts from this laconic statement to a close-up of Gregor’s tormented face, it renders his inability to cope with this dismissal of the Jewish victims as “Russians,” with the effacement of their difference. This tension defines Gregor’s identity: he is not prepared to identify himself as (merely) Jewish, and cannot feel (merely) Russian or German. He can feel at home only in the space that lies in-between these fixed identities. Accordingly, this portrayal of the tensions inherent to his identity occurs at a rare moment in the film, in which Gregor—taking a shower—engages in an activity normally performed in private, at home. This is, however, a privacy of isolation. Gregor’s silent defiance in the shower-room highlights his inability to express and communicate self-identity in private.

4. “I am German”: Heimat as a Sphere of Deception and Violence

The aforementioned opening scene encapsulates Wolf’s attitude toward the sentiments aroused by the concept of Heimat and its role in German national identity. The river, the hills, and the rafts on the foggy water convey the impression of a nostalgic postcard of generic German scenery and the human activity integrated peacefully within it. They appear to confirm the idea of a pre-modern German sphere that embodies national values and glory unaffected by the defeats of the fatherland. It soon becomes apparent, however, that this is the sphere of defeat. The sounds that accompany these images, the Red Army’s announcement of the German defeat, in effect split the image of the national landscape: the visual elements display an imaginary harmony, anchored in a particular national tradition but devoid of any particularities of time and space; the soundtrack, by contrast, locates the occurrences in a specific historical moment, specific territory, and a specific political context. Notably, the reason for this audio-visual anomaly—the call to surrender—is announced by the protagonist, whose story recounts Konrad Wolf’s own war-time experiences. Thus, the rupture in the Heimat image, and its alienating effect, is brought about by the particular presence of Konrad Wolf: it is he—a German-Jew and a devoted socialist – who cannot exist within the harmonious Heimat without ruining it. As an outsider, his mere presence in this imagined landscape tears it apart.

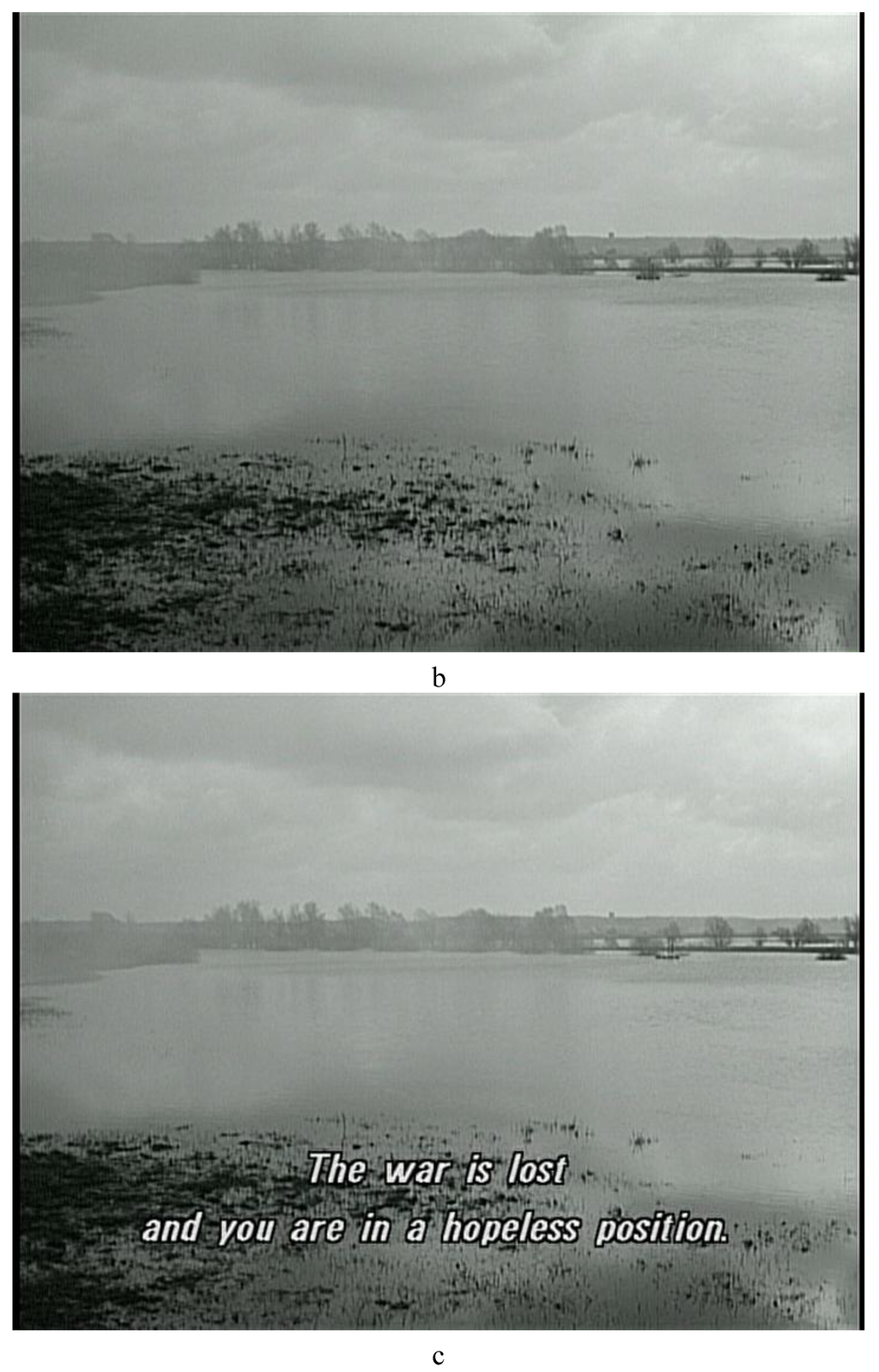

The disturbing presence of the (Jewish) outsider likewise underscores the nature of the fantasy embedded in the cultural encoding of the Heimat. It only exists as long as contemporary politics, violence and war, are overlooked. Notably, Wolf does not mourn the evaporation of the Heimat illusion, but is quick to demonstrate its potential menace. As the fog clears, it reveals the true nature of the leisurely floating “rafts”: rather than a traditional means of transportation, they serve as improvised gallows for people suspected of undermining the national war endeavor (Figure 2a and b). The Heimat landscape, the imagined a-political, authentic sphere, conceals the violence inflicted on the individual by the “homogenous” community. This conviction, which appears in different contexts in some of Wolf’s other films (most notably in Stars, Sterne, 1959), constitutes a fundamental principle in I was Nineteen; a key to its understanding as an attempt to rethink the rise and fall of East German nationality.

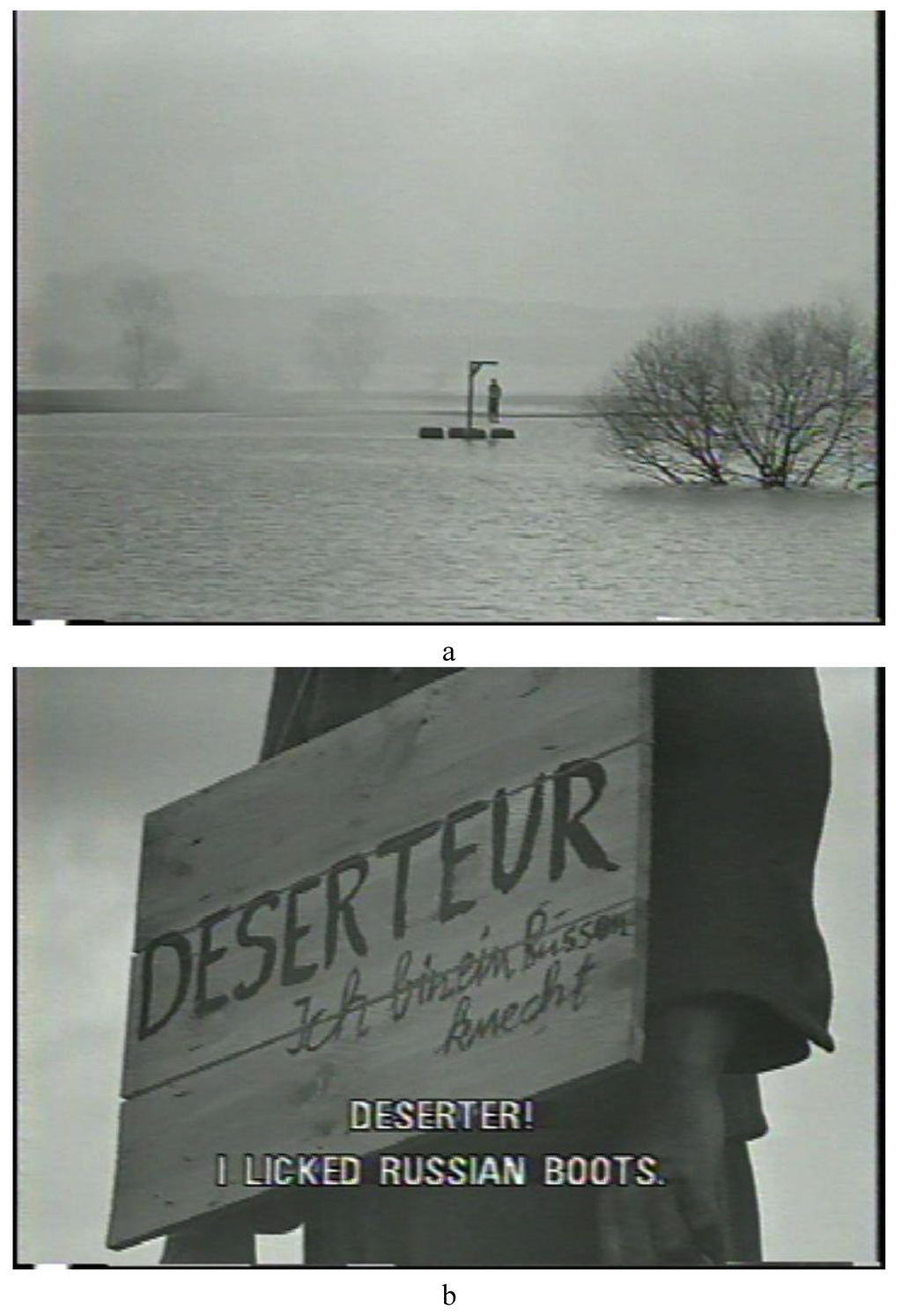

The presentation of the detached national landscape, untouched by modernity and war, as a realm of devastating deception is repeated throughout Gregor Hecker’s homecoming journey. It reaches its climax toward the end of the film, in a scene in which the protagonist and other exhausted Red Army soldiers find respite on a small hill by the side of the road. With a panoramic view of the rolling fields, scenery apparently unscathed by recent horrors, the men momentarily forget their role as combat soldiers, play games, and engage in sincere conversation. This idyll is interrupted when other Red Army tanks approach the field. As the weary young men wave to their comrades, the arriving tanks open lethal fire (Figure 3). It is quickly revealed that these tanks serve SS units in disguise, who continue with the killing despite the imminent end of the war. As in the opening scene, the iconographic Heimat imagery forms the backdrop to cruel—and redundant—violence; the feeling of being in the Heimat, in a place removed from the worries of the present, facilitates deception and its violent outcomes.

Figure 2.

a. A gallows looms above the foggy German river in I was Nineteen. b. A close look at reveals the reason for the brutal death: deviation from the shared beliefs and objectives of the national community

Figure 3.

SS-militants in Red Army tanks shoot at the resting soldiers. The serene landscape as a place of deception and senseless death.

The ultimate rejection of the ideas and sentiments associated with the imagery of Heimat is delivered in the film’s final scene. In the last moments of the war, Gregor stops his vehicle by a picturesque farmhouse and, together with his Russian commander and friend Sascha, convinces retreating German soldiers to lay down their weapons. In its composition, this scene mirrors the opening sequence. By contrast to the opening scene, however, this time the weary Wehrmacht men cross the narrow stream towards Gregor and throw down their guns as they accept that the war has come to an end. Strangely and reluctantly, Gregor senses an emotional bond with (or responsibility for) a young German soldier, and promises to deliver a letter from him to his family in Berlin. These emotions are expressed after the surrendering soldier reclaims his firearm. He now voluntarily fights alongside Gregor and Sascha against the remaining SS loyalists who drive along the other bank of the river and shoot at their capitulating compatriots. During the shooting, the little daughter of the farmers is caught in the line of fire, but is miraculously unharmed (thereby symbolizing, as in countless German films about the end of WWII, the future reconstruction of the nation by the young, innocent generation). Before this absurd incident is over, however, Gregor’s close Russian friend Sascha is fatally hit by a stray bullet.

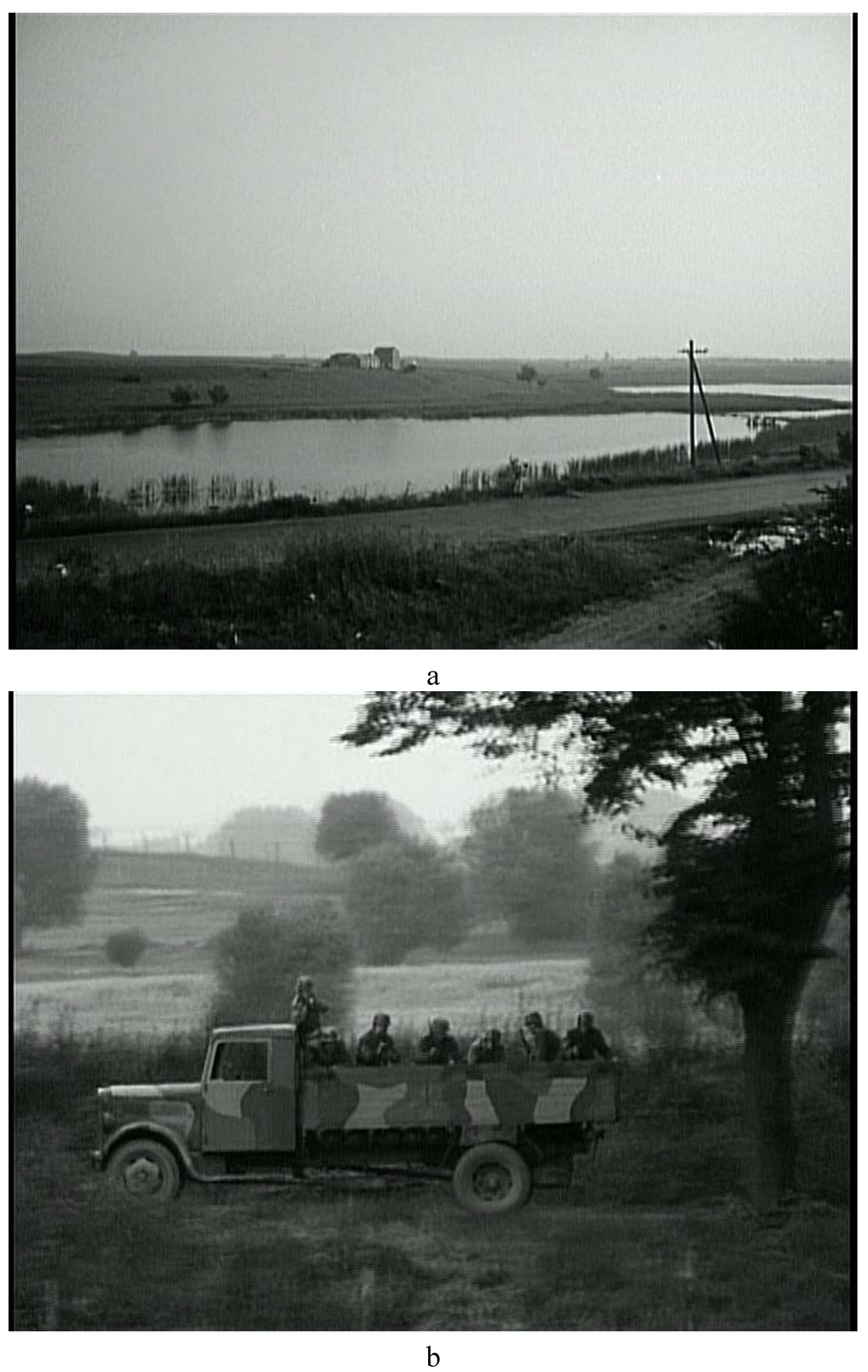

The shock of the meaningless death of his friend forms the backdrop against which the film presents a series of Heimat-style images. As in the opening scene, here too there is a conspicuous dissonance between the visual and audio elements of the image. And, once again, it is the voice of the protagonist, or of Konrad Wolf, that shatters the harmony of the imagined Heimat. As the Führer-loyalists drive away from the scene Gregor grabs the microphone—through which he previously declared the war to be over—and screams at the departing vehicles that his war has not ended, that he will continue “until you are dead […] until there’s no place left for you, nowhere on this planet; until you cannot shoot anymore, you criminals” (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Gregor Hecker’s voice interrupts the tranquil scenery and undermines the Heimatgefühl.

Furthermore, the most iconic Heimat image in this scene, and probably in the entire film, is displayed during the course of this desperate cry (Figure 5a). A wide-angle shot of the landscape includes the house and its barn (with cross-shaped windows, which allude to the Christian element of the landscape’s dwellers), some undistinguished hills in the background, a small river and some trees, alongside manmade components, such as dirt roads, a wooden fence, and even telegraph lines. This serene combination of old and new, human creation and nature, local and “typically” national is the essential aspect of Heimat-imagination, and the main source of its allure. Displayed first during a pause in Gregor’s monolog, this image seems almost detached from the violent conflict and the futile death that this place has witnessed. Wolf adds here a further layer to his disdain for the destructive deception of the concept of Heimat. This ideal image of harmony within the Heimat is shown here from a specific point of view: that of the SS-militants on the other bank of the river; this is the only perspective from which a homogenous community can be seen to prosper in its ‘authentic’ habitat (as becomes clear when Gregor’s point of view is shown, Figure 5b).

Figure 5.

a. I was Nineteen, final scene: harmony of man and nature from the SS point of view. b. Gregor’s point of view during the same scene shows the shooting SS-militants across the river.

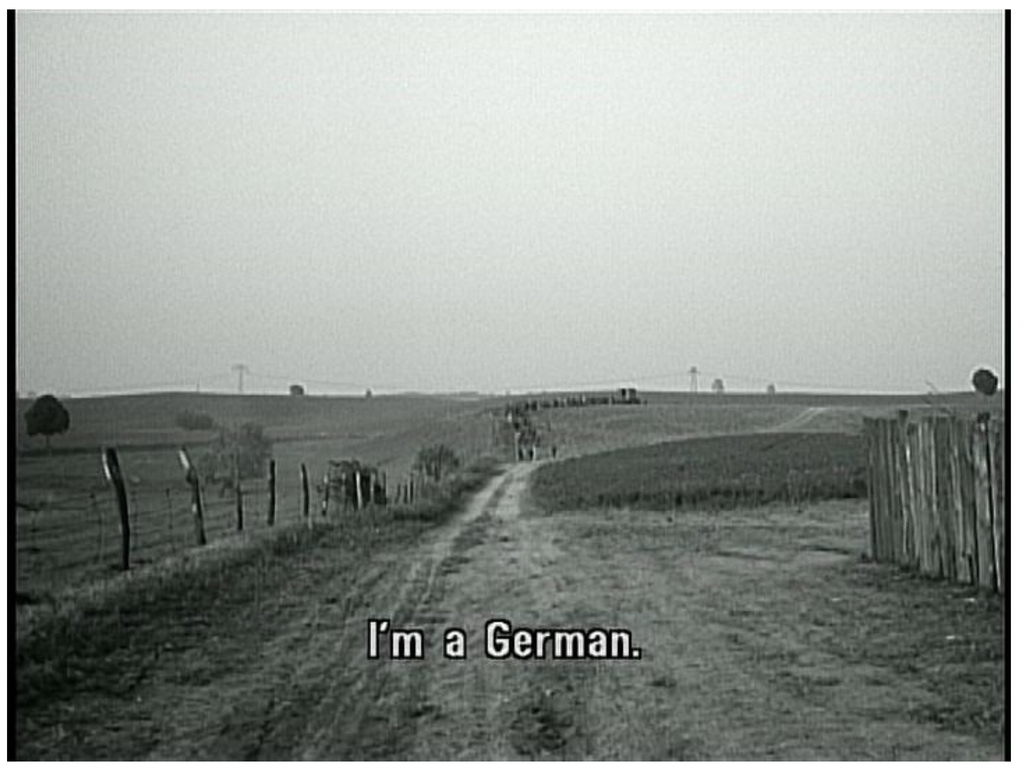

The concluding shot of the film is another Heimat-styled image, namely, a narrow dirt road in the midst of hilly fields. The human component of this image, however, does not signify a harmonious being-in the space, removed from modern conflicts, but rather portrays the exodus of Germans from the Heimat. A long line of defeated Wehrmacht soldiers is shown marching away from the camera, and away from the serene fields toward imprisonment and exile. In contrast to its conventional role in the German imagination, the Heimat here becomes the realm that manifests the results of politics in a most lurid manner. And this departure from the Heimat forms the backdrop to Wolf’s concluding statement, “I am German.” He can only be “German” when the Heimat as well as the ideals associated with it is deserted (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

The defeated German soldiers marching away from the Heimat scenery.

5. “I am German”? The Failure to Produce an Alternative National Sphere

To a large extent, therefore, I was Nineteen is a cinematic rejection of the premise of Heimat—i.e., of an authentic connection between the landscape and the homogenous community that dwells in it—and an exhibition of its destructive role in the formation of German national identity. Wolf goes further in this film, however, and endeavors to envisage an alternative public sphere, which could provide a new principle of collectivity to replace the Heimat’s ethnic homogeneity.

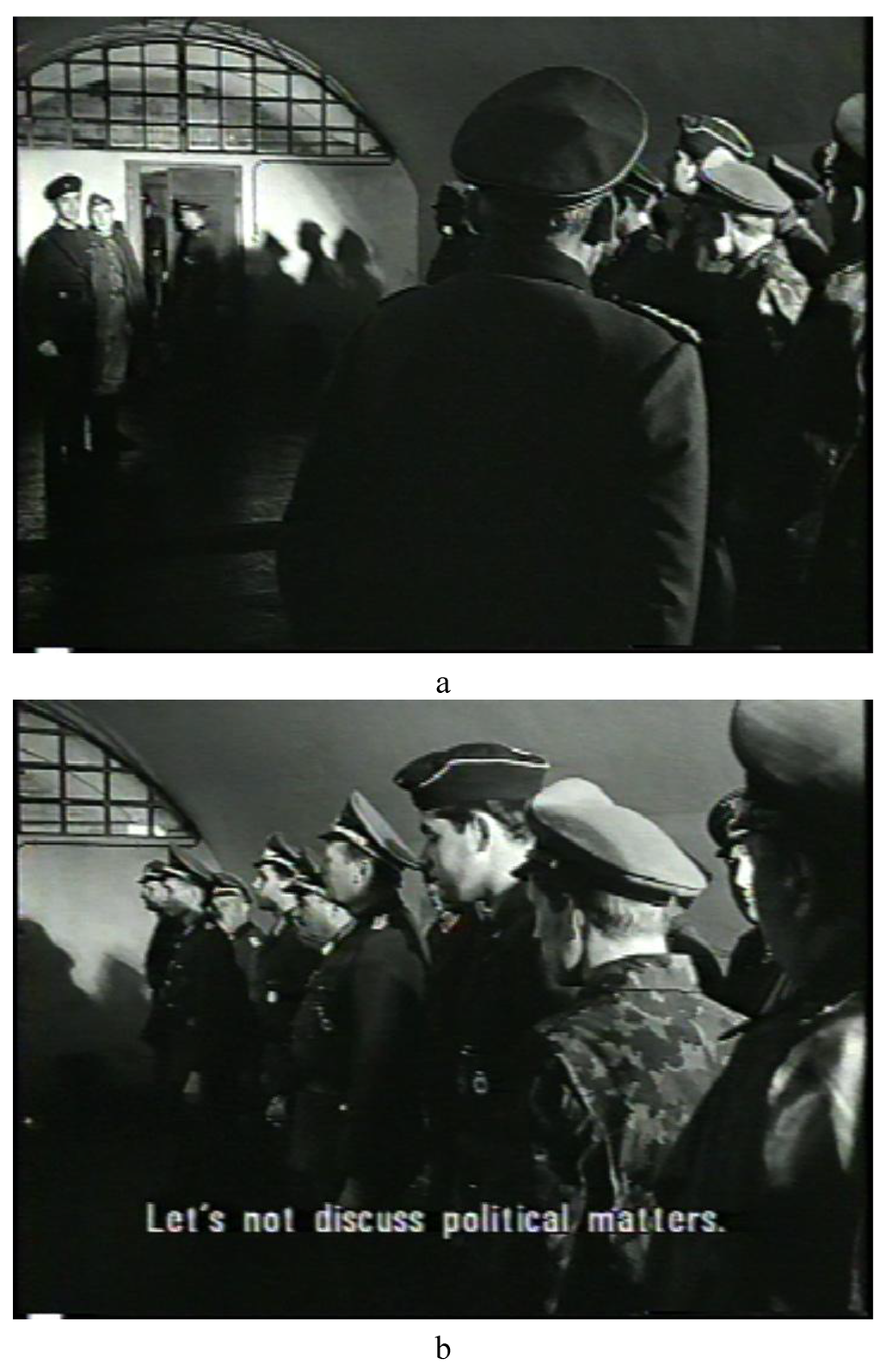

The key scene of I was Nineteen introduces an alternative German national sphere. In this scene, the protagonist and a fellow Soviet officer enter the dungeons of the Spandau fortress on the outskirts of Berlin to discuss the terms of surrender with the German soldiers, SS officers, and civilians who have taken refuge there. Deep underground, the meeting place affords an ephemeral impression of detachment from the outside world and in particular from the “German” landscape. It is nonetheless infused with politics: the protagonist urges the Germans—representatives of party and military institutions—to make a decision contrary to their standing orders and possibly their worldviews, namely, to capitulate and secure the lives of the wounded, of the women and children, and of the officers themselves. The subterranean hall in which the meeting takes place thus becomes a unique sphere from which a new Germany could emerge at the end of the war. The evolution of this new Germany is, however, dependent on the outcome of the (political) debate among the survivors, and between them and the Red Army delegates (Figure 7a). No wonder, therefore, that the devoted Nazis attending this meeting not only decline the offer, but also cut short the discussion, arguing that this is no time to “discuss political matters” (Figure 7b).

Figure 7.

a. Representatives of the different elements in GDR society discuss the condition for future cooperation. b. below: The command of the SS officer, not to “discuss political matters,” terminates the potential reconciliation.

The people gathered in the cellar of the fortress embody the different strata of the future GDR’s population and ideology: victims of Nazi aggression and (potentially reformed) servants of the Nazi war machine; German civilians who suffered the consequences of the Allied offensive, alongside a Jew returned from exile and a benevolent Soviet official. This scene in fact replicates a similar situation in Wolf’s earlier film Sun Seeker, in which the East-German uranium miners gather in a tunnel to debate the rationale and the outcomes of their labor. The group of miners likewise includes several elements of the new GDR, from former Nazis and devoted communists to Holocaust survivors, intellectuals, and rebellious youth. Eventually, through the lengthy discussions of the merits of their work, these different elements merge to form a community united by shared ideals and morals (the Heimat thus becomes an ideal public sphere, in Habermasian terms, in which objectives and policies are openly discussed and decided [45]). Unlike the miners’ ongoing debate, however, the encounter in the fortress portrayed in I was Nineteen ends without a political outcome that would bind the participants together despite (or because of) their differences. Symbolically, after the failure of the meeting the fortress is portrayed as a space that offers no hope for the future. In the following scene, a frantic young boy confesses to the savage killing of two Russian soldiers and wins a medal for bravery (implicitly, the SS officer who pins his own decorations on the boy exploits the occasion to rid himself of these incriminating insignia). Moreover, the SS officer who conspires to prevent capitulation sneaks away from the fortress to escape the consequences of his scheme. This ending of the scene does not merely subvert plain justice. It implies that any future society that evolves from the German catastrophe is likely to be founded by people like the escaped officer rather than by the obedient others, left in the fortress to die or to be expelled to POW camps in the Soviet Union. The final shot of this scene notably returns the viewers to the fantasy of a German landscape. As the SS-man escapes through the fortress’s underground tunnels, Gregor watches him rowing away on the peaceful lake to vanish amid the trees and the fog.

6. Conclusions

I was Nineteen is Wolf’s most elaborate attempt to envisage an alternative German identity, which would integrate ‘foreign’ elements through a shared vision and common objectives. The guiding principle of this film’s imagery is to manipulate the cultural imagination associated with the notion of Heimat in the post-World War II German nationality. Heimat films played an important role in the nation building endeavor of the Cold War era in West and East Germany alike. The ideas associated with this imaginary sphere implied the existence of an authentic German identity, detached from the conflicts and catastrophes of the twentieth-century, which would facilitate the reconciliation of social tensions within a homogeneous community. An exiled Communist Jew, Konrad Wolf’s identification with such a concept of community was always bound to be problematic. Yet Wolf was not a marginal or a subversive artist; he was a most prominent representative of GDR national culture, who fervently identified with what he interpreted as the objectives and ideology of the ruling socialist party.

Wolf’s manipulation of Heimat symbolism provided a particular cultural context for his films, and transformed them from the realm of individual psychology to that of collective (German) identity. Through its ironic use of the audio-visual clichés of the Heimatfilm genre, I was Nineteen’s imagery associates the horrors of German history with the longing for harmonious integration of old and new, and the nostalgic yearning to melt down different individuals into a (‘natural’) sense of homogenous collectivity. In a much cited essay on modern society, Georg Simmel characterized “the stranger” as an indispensible part of the modern environment that inevitably expresses “externality and contradictions” [46]; such characteristics were attributed often to the bourgeois urban Jew in pre-1933 Germany [47]. Wolf seems to be fascinated by this trope, but his “strangers” are elements in a post-bourgeois vision, of the kind (he believed to be) offered by the SED. Through the wry utilization of generic Heimat imagery Wolf envisioned an ideal socialist society, in which the acculturation of various “strangers” is the social norm.

More than any other German-Jewish film, I was Nineteen is a personal odyssey into the German community. It begins with Wolf’s protagonist as an outsider who calls upon the Germans on the opposite bank of the river to surrender, and ends with Wolf’s voiceover declaration, “I am German. I was Nineteen.” This self-proclamation as German notwithstanding, at the end of this odyssey Wolf is not entirely at home. As throughout the film, he is now again in motion, driving away from the camera through the landscape, rather than residing in it. Thus, while Wolf openly regarded his Jewish origins as a matter-of-fact feature of his biography, and seemingly refused to enter the German cultural-intellectual discourse as a Jew, his contribution to this discourse explores the unique perspective of an inherent outsider who strives to be acknowledged as part of the collectivity despite, or perhaps because of, his otherness. Situated well within the tradition of German-Jewish film-making since the early 1920s [48], he therefore offers a distinctively “Jewish” sense of German nationalism, which encompasses (and is based upon) the idea of cultural and social symbiosis. In this regard, Konrad Wolf’s perception of East German history is a unique demonstration of the way in which returning Jewish émigrés helped to shape German self-consciousness during the formative years of the Cold War.

References and Notes

- J. von Moltke. No Place like Home: Locations of Heimat in German Cinema. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005, p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- C. Applegate. A nation of provincials: the German idea of Heimat. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990, Volume 18, p. 77. [Google Scholar]

- A. Confino. The nation as a local metaphor: Württemberg, Imperial Germany, and National Memory, 1871–1918. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- T. Lekan. Imagining the Nation in Nature: Landscape Preservation and German Identity, 1885–1945. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- A. Bastian. Der Heimat-Begriff: eine begriffsgeschichtliche Untersuchung in verschiedenen Funktionsbereichen der deutschen Sprache. Tübingen: Niemeyer, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- K. Wolf. “Selbstaüsserungen.” Sinn und Form 35, 5 (1984): 897–900, here 900. [Google Scholar]

- A. Kaes. From Hitler to Heimat: The Return of History as Film. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1992, pp. 165–166. [Google Scholar]

- A. Confino. The nation as a local metaphor: Württemberg, Imperial Germany, and National Memory, 1871–1918. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- B. Waldenfels. “Heimat in der Fremde.” In Heimat: Analysen, Themen, Perspektiven. Edited by W. Cremer and A. Klein. Bonn: Bundeszenrale für Politische Bildung, 1990, pp. 109–121. [Google Scholar]

- A. Confino. “The Nation as a Local Metaphor, Heimat, National Memory and the German Empire, 1871–1918.” History and Memory 5, 1 (1993): 42–85, here 58, 64. [Google Scholar]

- C. Applegate. A Nation of Provincials, 1–19.

- J. A. Williams. Turning to Nature in Germany: Hiking, Nudism and Conservation, 1900–1940. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 2007, pp. 219–257. [Google Scholar]

- M. Umbach. German Cities and Bourgeois Modernism, 1890–1924. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009, pp. 64–68. [Google Scholar]

- T. Tönnis. Gemeinschaft und Gesellschaft: Grundbegriffe der reinen Soziologie. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 1988[1887]. [Google Scholar]

- H. G. Pflaum. Film in der BRD. Berlin: Henschelverlag, 1990, p. 23. [Google Scholar]

- T. Elsaesser. New German Cinema: A History. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1989, p. 141. [Google Scholar]

- R. Rentschler. “Mountains and Modernity: Relocating the Bergfilm.” New German Critique 51 (1990): 137–161. [Google Scholar]

- H. Fehrenbach. Cinema in Democratizing Germany: Reconstructing National Identity after Hitler. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995, p. 148ff. [Google Scholar]

- A. Confino. Germany as a Culture of Remembrance: Promises and Limits of Writing History. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996, pp. 92–113. [Google Scholar]

- J. von Moltke. No Place like Home, 170–202.

- J. Palmowsky. “Building an East German Nation: The Construction of a Socialist Heimat, 1945–1961.” Central European History 37, 3 (2004): 365–399. [Google Scholar]

- T. Lindenberger. “Home Sweet Home: Desperately Seeking Heimat in Early DEFA Films.” Film History 18, 1 (2006): 46–58, here 53ff. [Google Scholar]

- G. Scholem. “Against the Myth of German-Jewish Dialogue.” In On Jews and Judaism in Crisis: Selected Essays. Edited by W. J. Dannhauser. New York: Schocken Books, 1976, pp. 61–64. [Google Scholar]

- H. Arendt. “The Jew as Pariah: A Hidden Tradition.” Jewish Social Studies 6, 2 (1944): 99–122, here 99–100. [Google Scholar]

- A. Funkenstein. “The Dialectic of Assimilation.” Jewish Social Studies 1, 2 (1995): 1–14, here 10. [Google Scholar]

- S. E. Aschheim. “German History and German Jewry: Boundaries, Junctions and Interdependence.” Leo Baeck Institute Yearbook XLIII (1998): 315–323, here 320–321. [Google Scholar]

- Samuel. Moyn. “German Jewry and the Question of Identity.” Leo Baeck Institute Yearbook XLI (1996): 292–308, here 295. [Google Scholar]

- J. Zipes. “The Negative German Jewish Symbiosis.” In Insiders and outsiders: Jewish and Gentile Culture in Germany and Austria. Edited by Dagmar. C.G. Lorenz and Gabriele. Weinberger. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1994, pp. 144–154. [Google Scholar]

- D. Diner. “Negative Symbiosis: Germans and Jews after Auschwitz.” In Reworking the past: Hitler, the Holocaust, and the Historians Debate. Edited by P. Baldwin. Boston: Beacon Press, 1990, pp. 251–261. [Google Scholar]

- R. Ostow. “The Shaping of the Jewish Identity in the German Democratic Republic, 1949–1989.” Critical Sociology 17, 3 (1990): 47–59, here 52–53. [Google Scholar]

- K. Hartewig. Zurückgekehrt. Die Geschichte der jüdischen Kommunisten in der DDR. Köln: Böhlau Verlag, 2000, pp. 286–293. [Google Scholar]

- M. Richarz. “Jews in Today’s Germanies.” Leo Baeck Institute Yearbook XXX (1985): 126–130, 127. [Google Scholar]

- J. Herf. Divided Memory: The Nazi Past in the Two Germanys. Boston: Harvard University Press, 1997, pp. 106–200. [Google Scholar]

- G. Koch, and J. Gaines. “On the Disappearance of the Dead among the Living: The Holocaust and the Confusion of Identities in Konrad Wolf’s Films.” New German Critique 60 (1993): 57–75, here 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K. Hartewig. “Die Loyalitätsfalle: Jüdische Kommunisten in der DDR.” In Zwischen Politik und Kultur. Juden in der DDR. Edited by Moshe Zuckermann. Göttingen: Wallstein Verlag, 2003, pp. 48–62. [Google Scholar]

- M. Kessler. Die SED und die Juden – zwischen Repression und Toleranz. Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 1995, pp. 119–120. [Google Scholar]

- R. Guyonnet. “‘Etoile’: une Revendication bouleveresant de la vie Privée contre le siècle.” L’Express. 3 March 1960. [Google Scholar]

- K. Wolf. “On the Possibility of Socialist Film Art: Reactions to Mama, I’m Alive (1977).” In German Essays on Film. Edited by R. W. McCormick and A. Guenther-Pal. New York: Continuum, 2004, pp. 228–229. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf’s support for the Socialist enterprise is repeatedly manifested also in the 1985 published collection of his speeches, essays and interviews: D. Heinze, and L. Hoffmann, eds. Konrad Wolf im Dialog. Künste und Politik. Berlin: Dietz Verlag, 1985.

- W. Teichmann. “Es geht um die Kultur des Gefühls. Fortsetzung der Diskussion über Einmal ist keinmal.” Deutsche Filmkunst 5 (1995): 225–227. [Google Scholar]

- M. Silberman. “Remembering History: The Film-maker Konrad Wolf.” New German Critique 49 (1990): 163–191. [Google Scholar]

- S. Hake. “Political Affect: Antifascism and the Second World War in Frank Beyer and Konrad Wolf.” In Screening War: Perspectives on German Suffering. Edited by P. Cook and M. Silberman. Rochester: Camden House, 2010, pp. 102–122, here 102. [Google Scholar]

- A. Bastian. Der Heimat-Begriff: eine begriffsgeschichtliche Untersuchung in verschiedenen Funktionsbereichen der deutschen Sprache 33 (1995): 42.

- K. Schliephake, and S. Orf. “Heimatbindung und -verständnis von Repräsentanten des öffentlichen Lebens.” Beiträge Region und Nachhaltigkeit 3 (2006): 89–102, here 97. [Google Scholar]

- J. Habermas. The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere. Translated by T. Burger. Boston: MIT Press, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- G. Simmel. Sociology: inquiries into the construction of social forms Volume 1 Brill, Leiden. (2009 [1908]): 601–620.

- P. Mendes-Flohr. “The Berlin Jew as Cosmopolitan.” In Berlin Metropolis: Jews and the New Culture, 1890–1918. Edited by E. D. Bilsky. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999, pp. 14–21, here 21–22. [Google Scholar]

- Compare with O. Ashkenazi. Weimar Film and Modern Jewish Identity. New York: Palgrave-Macmillan, 2012, pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

© 2012 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).