Abstract

This research paper explores Romanian Orthodox religious places as vital centers for producing and promoting national identity as well as cultural and religious heritage in Italy. Through the application of a spatial perspective, it addresses the complexities of heritage recognition, questioning what constitutes “heritage” for the religious minorities in Italy and highlighting the inadequacies of the current legal frameworks in this context. The paper focuses on the interplay between history and memory, scrutinizing the dialectical relationships that shape polyphonic, collective, and public memories of the Romanian parishes’ national and religious heritage. Moreover, it analyzes how memories, traditions, and national identity influence the perception of religious communities by focusing on constructing a group memory that highlights ethnic identity rather than religious affiliation.

1. Introduction

Through the application of the spatial perspective to heritage, this article analyzes Romanian Orthodox places of worship in Italy as central hubs for the production, propagation, and preservation of religious, cultural, and national heritage.1

The theme of religious heritage sheds light on a dialog on the dialectical relationship between history and memory, highlighting concepts such as polyphonic memories, shared versus divisive memories, collective memory, and public memory. The sources utilized in this article encompass a diverse range of materials. Following a comprehensive review and discussion of both international and national literature on cultural and religious heritage, and in conjunction with the critical perspective emphasized in the introduction of this Special Issue, we examined the available legal documents pertaining to Italian civil law and Romanian Orthodox religious law.

The most substantial section of this article is founded on a field study conducted between 2023 and 2024, during which we carried out eight interviews, in both Italian and Romanian, and conducted fieldwork in five different parishes. Following this introduction, Section 2 presents a legal framework for religious heritage in Italy, highlighting the need for explicit norms regarding the protection and preservation of religious heritage for religions other than Catholic. Section 3 focuses on the legal framework governing the Romanian Orthodox heritage, emphasizing how the Romanian Diocese of Italy’s by-law explicitly addresses religious heritage, while implicitly referencing cultural heritage. Finally, Section 4 examines Romanian parishes as spaces of Romanian heritage in a pluriform sense, encompassing religious, cultural, and national dimensions. This section is based on information gathered from interviews conducted in parishes, highlighting how these spaces embody and reflect Romanian identity.

2. Religious Heritage in Italy: A Juridical Framework

From our viewpoint and within the context of this Special Issue, the sites associated with religious minorities represent the essence of both tangible and intangible religious heritage, and are considered a distinctive subcategory within the broader field of cultural heritage, as the editors of this Special Issue explained in the Introduction.

In Italy, the different non-Catholic groups have their unique interpretations of “cultural heritage”, each highlighting various historical, ethical, or material components. Although there are dedicated commissions that support some of these groups, the Italian government’s decisions regarding the recognition and protection of religious heritages, other than Catholic, remain uncertain (Long 1995). This ambiguity is also reflected in the provisions set forth in the agreements (the so-called “intese”) with certain religious groups, established by the Italian state in accordance with Article 8 of the Italian Constitution.2 However, Article 9 of the Italian Constitution underscores the Republic’s role in promoting culture and safeguarding the natural landscape, as well as the historical and artistic heritage. Within this framework, Article 9, Section 1 of the Code of Cultural Goods and Landscape (also known as “Urbani Code”), from 22 January 2004,3 stipulates that the Ministry of Cultural Heritage and, where applicable, the Regions are responsible for addressing the requirements of the religious cultural heritage belonging to the bodies and institutions of the Catholic Church and other religious denominations, according to the needs of worship, and in agreement with their respective authorities (Tsivolas 2014).

Nevertheless, despite the possibility of an official agreement, the “other religious denominations” remain poorly regulated compared to the Catholic Church. The Lateran Pacts of 1929 sanctioned the possibility for scholars and visitors to see the artistic and scientific treasures in Vatican City and the Lateran Palace, subject to regulation by the Holy See. The revision in 1984 included more specific provisions for the protection of the historical and artistic heritage,4 focusing on the preservation and consultation of archives, the use of libraries, and the custody, maintenance, and preservation of catacombs and relics (Colaianni 2012; quoting Losavio 1985). Thus, this revision had and has an ongoing regard for the protection of this valuable heritage. One of the most recent steps was the signing of an agreement between the Ministry of National Heritage and Culture and the Italian Catholic Episcopal Conference on 26 January 2005, which addresses the protection of cultural properties belonging to ecclesiastical institutions (Madonna 2007; Tsivolas 2014).

In the background and on the margins, questions concerning religious heritage have been incorporated into the text of several agreements. As Theodosios Tsivolas recalls, these include agreements with the Waldensian Evangelical Church, the Seventh-Day Adventist Church, the Assemblies of God in Italy, the Baptist Evangelical Christian Union of Italy, the Lutheran Evangelical Church, the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of Italy, and the Jewish Community (Tsivolas 2014). A reading of these agreements reveals that the phrase “cultural assets pertaining to the historical and cultural heritage” is repeated in various texts, with some variations. For example, in both the Waldensian Agreement and the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Italy the reference is made to cultural assets pertaining to the historical, moral and material heritage. In the Agreement with the Jewish communities instead, it concerns, more specifically, “assets pertaining to the historical and artistic, cultural, environmental and architectural, archeological, archival and book heritage” (Tsivolas 2014, p. 155).5 Jewish communities, within a framework of specific protection, have also benefited from numerous restoration and conservation activities, particularly in the early 2000s (Chizzoniti 2008; Tsivolas 2014).6

The regulatory framework is even more ambiguous and unregulated for religions without an Agreement, such as Islam and Romanian Orthodox Christianity, which are among the largest religious communities after Catholicism. Furthermore, the limited protections raise concerns about potential discrimination due to the lack of adequate recognition. This situation has also impacted the literature on religious heritage, as most of the research emphasizes the contributions of Catholic ecclesiastical institutions. This has resulted in a significant imbalance within the academic discussions surrounding the Catholic heritage, which has been extensively documented (from Armellini (1891) to Bartolozzi (2017)) or addressed in specific instances (Portoghesi 2019), while a thorough historiography on the other religions’ heritages remains largely absent. A major part of the literature concerning Italian religious heritage tackles Catholic architecture, churches, and monasteries, as well as the history of arts and objects.

Following the suggestion from the Introduction of this special issue regarding the application of the Spatial Turn to religious heritage, we will refer in particular to religious sites. When examining religious sites specifically, it becomes clear that there is a significant gap in the regulations regarding non-Catholic places, observable at both national and local levels. Since 1870, when Rome became a part of the Kingdom of Italy, and the Albertine Statute was applied to the city, granting it its unique city-state status as the home of the Church, the legal framework governing religious buildings has remained fragmented and insufficient through various key historical moments and continues to be inadequate today (Botti 2014; Marchei 2018; Cozma and Giorda 2021; Bossi 2024). In accordance with Article 8 of the Constitution, each religious group may independently determine the rules for identifying and managing its places of worship. Therefore, in the absence of a precise legal framework, many religious places—and not only Catholic churches—are scattered throughout the territory, frequented and animated by millions of people, suspended between visibility and invisibility, formality and informality.

The national law provides for a regulation that was created and designed for the Catholic Church, which, although applicable to “other” religions, has been interpreted in an extremely varied manner. For example, Article 4, §2.e of the Law no. 847 of 1964 established that “churches and other religious buildings” should be classified as secondary urbanization buildings.7 The Ministry of Public Works Circular No. 425/29 from January 1967 considered a parish church for a population of 5000 to 10,000 inhabitants.8 Ministerial Decree No. 1444/2 April 1968, concerning urban planning standards, through Article 3 established two square meters for facilities of common interest, including religious facilities.9 In addition, more recently, the construction of places for worship has been regulated by common law governing building and town planning through Presidential Decree No 380 of 6 June 2001, known as Testo Unico delle Disposizioni Legislative e Regulari in materia di edilizia (Consolidated Text of Legislative and Regulatory Provisions on Building)10. This decree reaffirms the delegation of the building authority to the regions and municipalities. However, at the national level, there are few sources of regulation, and these are often inconsistent or even contradictory (Giorda 2023).

The picture does not become clearer if one considers the regional dimension, which has its own legislative competence in the area of religious buildings: regional institutions, in fact, may diverge in their interpretation of the 1964 law and in the criteria for the allocation of areas to the Catholic Church or to other denominations, outlining an example of a restrictive interpretation of the formula “churches and other religious buildings” contained in the same law.

Different political orientations have led and may lead to legal measures that constitute an ambiguous and ever-changing legislative framework, with an impact not only on civil and religious rights, security, and (non)discrimination, but also on cultural, social, and cultural activities and economic opportunities (Giorda 2023).

3. Romanian Orthodox Heritage in Italy: A Legal Framework

The Romanian Orthodox heritage in Italy serves as a tool to verify the Italian political will to protect religious identities in a pluralistic society. This effort extends beyond the historically dominant Catholic tradition, recognizing the presence and contributions of other religious groups. By acknowledging Romanian Orthodoxy as part of Italy’s religious landscape, the Italian state demonstrates its commitment to pluralism and inclusion. This recognition aligns with the historical dimension, as it reflects an institutional effort to document, preserve, and integrate the heritage of minority groups within the broader narrative of Italian society. Memory is a subjective and collective phenomenon, shaped by the identities, experiences, and emotions of communities (Wang 2008; Heersminsk 2023). The interplay between the different dimensions of memories is particularly relevant when examining religious history as it reveals both the sociopolitical dynamics and the lived experiences of communities.

Simultaneously, this heritage represents an expression of memory for the Romanian community in Italy. It embodies a collective identity that connects the migrants to their homeland and their religious traditions. For the Romanian state, Orthodoxy plays a critical role in fostering national cohesion and belonging, even beyond its borders (Cozma 2020; Cozma and Giorda 2021; Crețu 2022; Șelaru 2022). The religious ties of the diaspora are used as means to cement the Romanian national political identity among migrants in Italy. This use of memory emphasizes the emotional and symbolic power of religious practices and institutions in maintaining a sense of unity and continuity within a dispersed community (Ang 2011).

The relationship between history and memory underscores the dynamic and dialectical balances between the political elements associated with the nation-state and the religious influences. These forces operate within a complex dialectic involving the concepts of minorities and majorities (Pizzorusso 1993; Giorda and Mastromarino 2020). From the perspective of the Italian State, accommodating Romanian Orthodoxy involves navigating the balance between integrating a minority group and maintaining the coherence of a diverse national identity. For the Romanian state, it involves leveraging the religious memory of its diaspora to reinforce national identity without alienating its emigrants from their host society. The Romanian Orthodox heritage in Italy exemplifies the intersection of history and memory in shaping both political and religious landscapes. The historical acknowledgment of this heritage fosters institutional inclusion and pluralism, while its role as a carrier of memory strengthens the cultural and spiritual bonds within the Romanian diaspora. This interplay highlights the broader dynamics of how states and communities negotiate identity, belonging, and coexistence.

The junction of history and memory intercepts the theme of constructing a national group memory, as exemplified by the Christian Catholic heritage that has shaped Italians and Italy, as well as the Romanian Orthodox heritage that has defined Romania. Therefore, the question arises: how much does the memory of the material and immaterial elements of a heritage contribute to forming an idea not only of a group/religious community but of the nation? To what extent does the concept of ‘heritage’ encompass not only cultural and religious dimensions, but also political aspects?

Although there is no formal agreement between the Italian State and the Romanian Orthodox Episcopate in Italy, the diocese has been recognized as an “ente di culto” with a legal personality, having been listed among the so-called “admitted cults” (“culti ammessi”) by presidential decree on 12 September 2011 (Cozma and Giorda 2022; Giorda 2023). This legal status has enabled the diocese to have its own patrimony and provides legal coverage for its 478 cult entities, which include parishes, monasteries, and missions. According to the Statute of the Romanian diocese (2008, with subsequent updates)11, the diocese patrimony is categorized based on its intended use of sacred and common goods (Art. 73/1). Sacred goods are intended solely for worship, while common goods are utilized for the maintenance of places of worship, the clergy, and for cultural, charitable, and social initiatives (Art. 73/2–3). Thus, this statute entitles the diocese and parishes to manage their own patrimony. Furthermore, to support its cultural activities, the diocese may engage in economic activities through its parishes and monasteries, provided these do not contravene Orthodox tradition and comply with Italian law (Art. 70).

The concept of “patrimony”, as indicated by interviews with several Romanian priests in Italy, is understood in a broad context, encompassing both cultural and religious heritage.

As we can see from the diocesan bylaw, the term “cultural” (mentioned 23 times in the Statute) is, in many cases, either associated with the notion of patrimony or implicitly allows an interpretation in this sense. Thus, the terminology used includes “cultural goods”, “cultural establishments”, “cultural activities”, and “cultural programs”, with explicit or implicit references to the administrative and executive bodies responsible for managing the diocese’s patrimony and assets, such as the Eparchial Assembly (Art. 15/b-c) and the Eparchial Council (Art. 17 and Art. 20/g).

Article 23/i underscores that the tasks of the Diocesan Standing Committee also include engagement with Italian central and local authorities “to obtain funding for the missionary-pastoral, cultural, and social-philanthropic activities of the Diocese and its units, as well as for the construction of new churches within the Diocese”. This provision seems to represent an effort to establish a legal framework for public funding to support the activities of parishes, including their cultural activities.

At the parish level, parish priests are responsible for administering the parish patrimony in accordance with the decisions made by the Parish Assembly and the Parish Council (Art. 37/j); they also oversee the management of assets belonging to cultural, social-philanthropic institutions, and ecclesiastical foundations within the parish. The Parish Assembly is tasked with deciding on the establishment of funds for ecclesiastical, cultural, or social-philanthropic purposes, as well as formulating rules to supplement the financial resources necessary for the parish (Art. 41/f). Additionally, it approves measures regarding the administration of movable and immovable properties belonging to a parish, ensuring proper maintenance of ecclesiastical, cultural, social-philanthropic, and foundation buildings (Art. 41/k). Furthermore, the parish committee holds responsibilities for cultural services (Art. 53/2c).

Therefore, Romanian Orthodox parishes are seen as vital instruments for the preservation and transmission of Romanian heritage abroad, encompassing both tangible and intangible forms, and defined by a blend of religious, cultural, national/ethnic, and political elements.

Patriarch Daniel of the Romanian Orthodox Church outlined, in a speech in 2018, dedicated to the celebrations of the Centenary of the Great Union of all Romanians, that Romanian cultural heritage is, to a large extent, rooted in religious heritage.12 This interdependence between cultural and religious heritage is further highlighted by Vasile Crețu in his 2022 work on Romanians in the diaspora. He argues that the active involvement of the Romanian Church in its communities abroad enriches the European society with Romanian spirituality and culture, particularly its religious values. He states:

Within the Romanian Orthodox communities in the diaspora, the traditions of the Romanian village have been embraced and nurtured with great passion, playing a significant role in the socio-cultural development of the parishes. From the observance of Easter and Christmas customs to the traditions relating to the baptism of infants, religious weddings, National Day, Mother’s Day, Christian women’s day and traditional clothing, Romanians from different corners of our country have interwoven the specific features of each area, thus giving rise to a cultural and religious heritage unique in form and content.(Crețu 2022, p. 7)

Moreover, Sorin Șelaru, the parish priest in Brussels and the Director of the Representation of the Romanian Orthodox Church to European Institutions, underscores that it is the responsibility of the Romanian Orthodox Church abroad to defend, strengthen, and nurture both the Orthodox faith and Romanian dignity (Șelaru 2022).

4. Romanian Orthodox Parishes in Italy: Spaces of a Romanian Heritage

In a continuous encroachment between sacred and secular, religious places are the active subjects and propellers of a historically increasingly dense sedimentation of a complex heritage, in which different histories, narratives and memories thicken (Lo Faro and Miceli 2021).

In fact, their recognition is not always the same, depending on whether they are observed and perceived by community members, local or national religious leaders, or social and political cultural institutions. In this research, we have adhered to the first and second levels, in an attempt to fill a small gap in heritage studies from a bottom-up perspective, as highlighted in the Introduction to this special issue.

If we assume religious places as a privileged space for the production, preservation, and transmission of Romanian heritage, parishes emerge as essential vantage points for researching both tangible and intangible heritage. Parishes serve as hubs where communities organize themselves, maintain traditions, and guard objects and works of art. From this perspective, by observing from below the mechanisms of heritage collection and visibility, our goal is to highlight the dynamics and strategies employed locally by church members to understand the extent to which heritage identity is first and foremost recognized by the communities themselves, while also exploring its religious, cultural, and political dimensions.

The tangible form of religious heritage is expressed through a distinctive architecture of religious places, particularly in traditional wooden churches. For example, of the 11 churches built ex novo in the last ten years, 4 of them exemplify the Romanian architectural style commonly known as the “Maramureş style”.

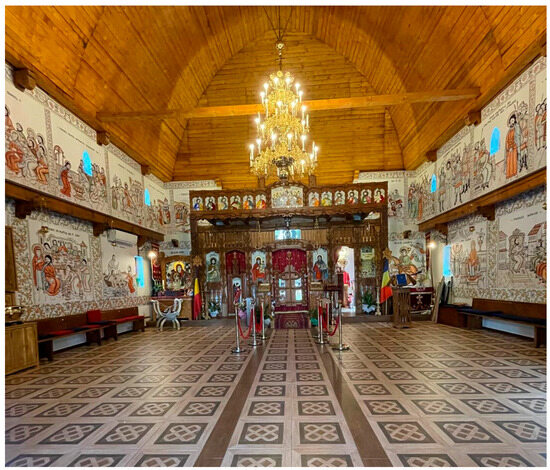

One among these churches is the church of Moncalieri in the province of Torino, which was built between 2013 and 2014 and is the first ever church built in this particular style in Italy (Cozma and Giorda 2022; Giorda 2023). All the wooden components and ornate carvings and shingles of this church were crafted in Romania by artisans from Maramureș, offering a unique design that provides a sense of both cultural and religious continuity and identity (Figure 1). Not only the exterior but also the interior of the church conveys a strong sense of belonging and continuity of the Romanian heritage. Interior murals depict saints dressed in traditional Romanian clothes, including images of the Virgin Mary with her child Jesus.

Figure 1.

The interior of the Holy Forty Martyrs Romanian Orthodox Church in Moncalieri (Turin). Photo credit: M. Floricu.

Paintings and icons play a significant role in Orthodox worship, serving as a means for the faithful to connect with heaven through the saints depicted on them. Moreover, it should be emphasized that paintings and icons are objects of sacred art that enrich the Romanian national cultural treasure; thus, as Patriarch Daniel outlined, through their presence in the Romanian churches, monasteries and hermitages, “these places of worship are included in the universal cultural heritage”.13

According to Fr. Marius, the parish priest of this church, a wooden church also holds cultural significance, reflecting the history and values of the Romanian people. For this reason, the authentic model must be followed precisely, even if it entails additional expenses (Fr. Marius, 14 June 2024; 9 December 2024). This was exemplified by the roof of this church, completed this year, nearly a decade after its consecration; the wooden shingles that cover it appear golden and stand out impressively against the rugged and traditional style of the surrounding buildings (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The Holy Forty Martyrs Romanian Orthodox Church in Moncalieri (Turin). Photo credit: M. Floricu.

For Fr. Lucian from the Romanian parish of Bolzano, the architectural traditional Romanian style is seen as proof of preserving the Romanian identity in Italy within a heritage of religious and cultural superdiversity, such as the Italian one (Fr. Lucian, 5 December 2024).

Worshippers attending the services in these traditional settings often feel more at “home”, as the environment resonates with the Romanian natural landscape (as it was already mentioned, the wood is sourced from Romanian forests) and reflects their cultural identity and shared history. Fr. Marius emphasized that the faithful from the Republic of Moldova who attend his church share the same sense of belonging as their Romanian brothers and sisters (Fr. Marius, 14 June 2024; 9 December 2024). Consequently, many believers have expressed that when they step into this church, they experience a deep connection to Romania, evoking a strong sense of belonging.

This sense of feeling “at home” in Romanian Orthodox places of worship can be felt throughout Italy, even if not all these sites are constructed anew in the traditional Romanian style. Each place of worship is thoughtfully decorated to reflect the interiors of Romanian churches as closely as possible. In an interview (12 June 2024), Fr. Gabriel, from one of the Romanian parishes in Turin, noted that the faithful prefer Orthodox places of worship that are traditional churches rather than secular spaces that have been converted into churches but lack authentic church architecture.

Completing the landscape of Romanian heritage shaped by tangible spaces is the use of the Romanian language in divine services, which serves as an intangible element; it is regarded as a vital instrument for transmitting national heritage and identity, as well as for preventing the cultural and spiritual alienation of Romanians living abroad. As Father Gabriel articulated (7 December 2024), “When you hear your own language, the pain of distance fades”. Furthermore, according to the Fr. Lucian, this linguistic connection allows the faithful to “forget” that they are in Italy and to “harmonize” culturally and spiritually with their Romanian relatives back home in Romania (Fr. Lucian, 5 December 2024).

However, this interplay between the secular (wooden components, popular art) and the sacred (church architecture), as well as between traditional (Romanian traditional clothing in iconographic depictions) and conventional representations, raises intriguing questions, such as, can there be a secular sacredness within a religious context? The response provided by Orthodox priests and believers is that the Romanian elements present in places of worship, such as those in Moncalieri, can serve as cultural markers that enhance the spiritual experience, blending national and ethnic heritage with faith.

National and ethnic heritage is often expressed through the preference of the Romanian faithful for traditional popular clothes during religious services, which reflects a strong expression of national and cultural pride (Figure 3 and Figure 4). Interviews have shown that many people feel that wearing traditional Romanian clothes strengthens their connection with their Romanian roots and Orthodox faith.

Figure 3.

Faithful of the Holy Forty Martyrs Romanian Orthodox parish wearing traditional clothes (Moncalieri). Photo credit: M. Floricu.

Figure 4.

Faithful of the Holy Cross Romanian Orthodox parish after the liturgy on Sunday (Turin). Photo credit: G. Burcescu.

Father Cristian-Viorel from Civita Castellana pointed out that “Wearing Romanian traditional popular attires in the church serves as a reminder of our past, encompassing its history, culture, and religion, while also establishing a connection with our ancestors and their traditions” (Fr. Cristian-Viorel, 4 December 2024).

Speaking about the Orthodox and Romanian identities, Father Cristian from Turin used a metaphor of a tree that must nurture and care for its roots to grow and thrive. He stated, “We are like a tree; the crown alone is not enough; solid roots are essential for growth and survival. Parishioners need to know who they are, what their history is, what the traditions are” (Fr. Cristian, 7 December 2024).

Romanian identity is displayed through the presence of the Romanian flag at places of worship, positioned either near the altar (see Figure 1) or at the entrance of certain churches. This identity is also celebrated by parishes through various Romanian national feasts that commemorate historical and cultural events, including National Culture Day (15 January); the Union of the two Romanian provinces (24 January) Wallachia and Moldavia; Mothers’ Day (8 March); Romanian Heroes’ Day (at the Ascension of the Lord); Romanian blouse day (24 June); Romanian Language Day (31 August); Romania’s National Day (1 December).

These civil feasts, part of Romania’s intangible heritage, are often celebrated on Sundays when more people can attend the church, being frequently accompanied by cultural events (i.e., patriotic songs and poems, exhibitions), presented by children from Sunday schools. Father Lucian emphasized that Romanian national holidays play a crucial role in helping Romanians remember their roots and simultaneously foster Romanian culture abroad. Moreover, he believes that nearly all national feasts have a spiritual “core” and are imbued with “religious elements” (Fr. Lucian, 5 December 2024).

Regarding the balance between Romanian identity and Italian belonging, for those who have resided in Italy for many years, the concept of a “hybrid identity” can be employed, which refers to a diasporic consciousness that oscillates between the Italian host country and the Romanian “lost home”, rich with memories, images, and stories (Ortega 2020; Șelaru 2022). However, the tension between integration and assimilation is less present for the second generation of Romanians, particularly those born there or at least arrived in Italy very young. For many of them, Romanian tends to become a second language, spoken only at home and in church. Father Cristian explained that “People often identify as both Romanian and Italian. However, even though they are connected to the places where they live and are socially and culturally integrated, they acknowledge that, deep down, they remain Romanian. Their roots continue to be Romanian, but in the interest of integration, they embrace their Italian identity” (Fr. Cristian, 10 May 2024; 7 December 2024). Furthermore, all priests interviewed stressed the significance of using the Romanian language in celebrations to preserve national identity and Romanian culture. With minor exceptions, all parishes from Italy provide Sunday schools where children are instructed not only in Orthodox religion but also in Romanian literature, history, and geography. This initiative is actively supported by both the Romanian Patriarchate and the Romanian government through various educational programs and projects.

In this process of maintaining and transmitting Romanian heritage, some priests interviewed view the involvement of the Romanian state as beneficial, while others consider it selective, often depending on the Church authorities’ preferences for specific parishes or priests. However, it is important to note that, according to official information from the Romanian Secretariat of State for Religious Cults, most clergy are employed at the Patriarchate as missionary priests and receive minimum economic assistance from the Romanian public budget. Furthermore, the parishes receive financial support through various projects funded by the Department for Romanians Abroad. It should also be noted that some priests also receive social benefits from the Italian state.

5. Concluding Remarks

The intertwining of religious, national, and cultural heritage manifests in different ways, resulting in a nuanced understanding of Romanian identity.

In reference to the interplay between Romanian identity and Italian affiliation, individuals who have lived in Italy for an extended period may utilize the term “hybridity”, which signifies a diasporic awareness that fluctuates between the Italian host nation and the Romanian home, imbued with memories, symbols, and narratives.

The notion of identity among these individuals is predominantly Orthodox, yet distinctly Romanian, as illustrated by their reflections on relationships with secular organizations. Although a consensus exists regarding the absence of conflict, it is nonetheless acknowledged that interventions by these organizations within the religious sphere are perceived as intrusive and inappropriate. In contrast, the Orthodox parish communities are seen as appropriate venues for organizing social and cultural events that facilitate the reconstruction and preservation of the ties to one’s homeland. Romania is regarded as a motherland that must be remembered, honored, and commemorated through mechanisms that can be described as a form of “civil religion” linked to Romanian Orthodoxy, within the porous boundaries of which a cultural hybrid heritage is both preserved and transmitted. The dichotomy between Italian and Romanian appears to be less pronounced among the second and third generation of Romanians, particularly those who were either born in Italy or relocated there at a very young age, but people seem to recognize themselves not only as Orthodox, but as Romanian.

We face a double kind of collective confusion and not only forms of hybridity; the first one is between history and memory, since the narration and the reconstruction of the memory is always a result of cultural and political aims. We can affirm that the collective memory of people, as it is represented by religious leaders, is more Romanian than Orthodox. The second typology of confusion and continuous hybridization is between Romanian national history and memory and Orthodox history and memory. However, the heritage that results is both Orthodox and national Romanian, but at the political level it is recognized, paradoxically, vice versa, as more political than religious, that is more Romanian than Orthodox.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.C. and M.C.G.; methodology, I.C. and M.C.G.; software, I.C.; validation, I.C. and M.C.G.; formal analysis, I.C. and M.C.G.; investigation, M.C.G.; resources, I.C. and M.C.G.; writing—original draft preparation, I.C. and M.C.G.; writing—review and editing, I.C. and M.C.G.; visualization, I.C. and M.C.G.; supervision, I.C. and M.C.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | This publication was realized within the framework of “Project PE 0000020 CHANGES—CUP F83B22000040006, NRP Mission 4 Component 2 Investment 1.3, and funded by the European Union—NextGenerationEU”. |

| 2 | Constitution of the Italian Republic: https://www.senato.it/documenti/repository/istituzione/costituzione_inglese.pdf (accessed on 13 December 2024). |

| 3 | Decreto Legislativo 22 gennaio 2004, n. 42, Codice dei beni culturali e del paesaggio, ai sensi dell’articolo 10 della legge n. 137, 6 luglio 2002. Gazzetta Ufficiale 45, 24 febbraio 2004, n. 28: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/atto/serie_generale/caricaDettaglioAtto/originario?atto.dataPubblicazioneGazzetta=2004-02-24&atto.codiceRedazionale=004G0066 (accessed on 13 December 2024). |

| 4 | See Article 12 §§ 1 and 2 of the Italy—Holy See Agreement of 1984 to Amend the Lateran Concordat of 1929: of 1984: Italy-The Holy See: Agreement to Amend the 1929 Lateran Concordat. International Legal Materials. 1985. 24(6): 1589. doi:10.1017/S0020782900060319. |

| 5 | Regarding the ongoing agreements, we have been unable to obtain any updates concerning the documents and draft materials. |

| 6 | See particularly (Tsivolas 2014, p. 156), note 158: Legge n. 175 del 17 agosto 2005, Disposizioni per la salvaguardia del patrimonio culturale ebraico in Italia, Gazzetta Ufficiale, 2 September 2005, n. 204; further information available online at the official web portal of the Fondazione per i Beni Culturali Ebraici in Italia: http://moked.it/fbcei (accessed on 13 December 2024). |

| 7 | Legge n. 847, 29 settembre 1964, Autorizzazione ai Comuni e loro Consorzi a contrarre mutui per l’acquisizione delle aree ai sensi della legge 18 aprile 1962, n. 167: https://www.normattiva.it/uri-res/N2Ls?urn:nir:stato:legge:1964-09-29;847~art4 (accessed on 13 December 2024). |

| 8 | Circolare ministero dei lavori pubblici n. 425, 29 gennaio 1967: http://architettura.it/notes/ns_nazionale/anno_60-69/CIRC.425-67.html (accessed 13 December 2024). |

| 9 | Decreto interministeriale n. 1444, 2 aprile 1968, Limiti inderogabili di densità edilizia, di altezza, di distanza fra i fabbricati e rapporti massimi tra gli spazi destinati agli insediamenti residenziali e produttivi e spazi pubblici o riservati alle attività collettive, al verde pubblico o a parcheggi, da osservare ai fini della formazione dei nuovi strumenti urbanistici o della revisione di quelli esistenti, ai sensi dell’art. 17 della legge n. 765 del 1967, Gazzetta Ufficiale 109, 16 aprile 1968, n. 97: 2341. https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/gu/1968/04/16/97/sg/pdf (accessed on 13 December 2024). |

| 10 | Decreto del Presidente della Repubblica n. 380, 6 giugno 2001: “Testo unico delle disposizioni legislative e regolamentari in materia edilizia. (Testo A)”, Gazzetta Ufficiale, 15 novembre 2001, n. 266 (246): https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/gu/2001/11/15/266/so/246/sg/pdf (accessed on 14 December 2024). |

| 11 | Chiesa ortodossa Romena, Lo statuto d’organizzazione e funzionamento della Diocesi ortodossa romena d’Italia: https://episcopia-italiei.it/ro/sl/7938-statutul-pentru-organizarea-i-funcionarea-episcopiei-ortodoxe-romane-a-italiei (accessed on 13 December 2024). |

| 12 | Speech by His Beatitude Daniel, Patriarch of the Romanian Orthodox Church, at the National Conference Dogmatic Unity and National Specificity in Church Painting, 6th edition, Tuesday, 29 May 2018, Patriarchal Palace in Bucharest. https://basilica.ro/arta-bisericeasca-un-tezaur-cultural-national-care-trebuie-conservat-imbogatit-si-evidentiat/ (accessed on 13 December 2024). |

| 13 | Message of His Beatitude His Beatitude Daniel, Patriarch of the Romanian Orthodox Church, on the Sunday of the Romanians Migrants, 20 August 2017 (first Sunday after the Feast of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary): https://basilica.ro/cinstire-si-recunostinta-marturisitorilor-credintei-ortodoxe/ (accessed on 13 December 2024). |

References

- Ang, Ien. 2011. Unsettling the National: Heritage and Diaspora. In Heritage, Memory & Identity. Edited by Helmut Anheier and Yudhishthir Raj Isar. The Culture of Globalisation Series 4; London: Sage, pp. 82–94. [Google Scholar]

- Armellini, Mariano. 1891. Le Chiese di Roma, dal Secolo IV al XIX, 2nd ed. Roma: Tipografia Vaticana. [Google Scholar]

- Bartolozzi, Carla, ed. 2017. Patrimonio Architettonico Religioso. Roma: Gangemi Editore. [Google Scholar]

- Bossi, Luca. 2024. Le Religioni e la Città. La Governance Locale Della Diversità. Mulino: Il Mulino. [Google Scholar]

- Botti, Federica. 2014. Edifici di culto e loro pertinenze, consumo del territorio e spending review. Stato, Chiese e Pluralismo Confessionale 27: 1–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chizzoniti, Antonio Giuseppe Maria. 2008. I beni culturali di interesse religioso: La collaborazione tra istituti pubblici ed ecclesiastici nell’attività di valorizzazione. In Cultura e Istituzioni, La valorizzazione dei Beni Culturali Negli Ordinamenti Giuridici. Edited by Lidianna Degrassi. Milano: Giuffré, pp. 63–104. [Google Scholar]

- Colaianni, Nicola. 2012. La tutela dei beni culturali di interesse religioso tra Costituzione e convenzioni con le confessioni religiose. Stato, Chiese e Pluralismo Confessionale 21: 551–66. [Google Scholar]

- Cozma, Ioan. 2020. Diaspora Ortodoxă: Canonicitate și imperative pastorale. In Biserica Ortodoxă și Provocările Viitorului. Edited by Mihai Himcinschi and Razvan Brudiu. Alba Iulia: Reintregirea & Presa Universitară Aeternitas, pp. 329–48. [Google Scholar]

- Cozma, Ioan, and Maria Chiara Giorda. 2021. Diaspora ortodoxă română în Italia:Strategii și dinamici în crearea și folosirea lăcașurilor de cult. Altarul Reintregirii 3: 37–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozma, Ioan, and Maria Chiara Giorda. 2022. Luoghi di culto della Chiesa ortodossa romena in Italia: Dinamiche di insediamento. In Le Chiese Romene in Italia. Percorsi, Pratiche e Identità. Edited by Marco Guglielmi. Roma: Carocci editore & Biblioteca di testi e studi, pp. 37–55. [Google Scholar]

- Crețu, Vasile. 2022. Românii în Diaspora. Migrație, Pastorație și Educație Religioasă. Bucharest: Cuvântul Vieții. [Google Scholar]

- Giorda, Maria Chiara. 2023. La Chiesa Ortodossa Romena in Italia. Per una Geografia Storico-Religiosa. Roma: Viella. [Google Scholar]

- Giorda, Maria Chiara, and Anna Mastromarino. 2020. Maggioranze e minoranze: Andare oltre? Le mense degli ospedali come laboratorio di analisi. In Diversità Culturale Come Cura, Cura Della Diversità Culturale. Edited by Beatrice Bertarini and Caterina Drigo. Torino: Giappichelli Editore, pp. 95–122. [Google Scholar]

- Heersminsk, Richard. 2023. Materialised Identities: Cultural Identity, Collective Memory, and Artifacts. Review of Philosophy and Psychology 14: 249–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Faro, Alessandro, and Alessia Miceli. 2021. New Life for Disused Religious Heritage: A Sustainable Approach. Sustainability 13: 8187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Gianni. 1995. Tutela e valorizzazione del patrimonio culturale nelle intese con le confessioni diverse dalla cattolica. In Beni Culturali di Interesse Religioso. Edited by Giorgio Feliciani. Bologna: Il Mulino, pp. 89–97. [Google Scholar]

- Losavio, Giovanni. 1985. I beni culturali ecclesiastici e il nuovo Concordato. Più difficile la tutela? Quaderni di Italia Nostra 19: 155. [Google Scholar]

- Madonna, Michele, ed. 2007. Patrimonio Culturale di Interesse Religioso in Italia: La Tutela Dopo l’Intesa del 26 Gennaio 2005. Venezia: Marcianum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Marchei, Natascia. 2018. Il “Diritto al Tempio”. Dai Vincoli Urbanistici alla Prevenzione Securitaria. Napoli: Editoriale Scientifica. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega, Gema. 2020. Where is home? Diaspora and hybridity in contemporary dialogue. Moderna Språk 114: 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzorusso, Alessandro. 1993. Minoranze e Maggioranze. Torino: Einaudi. [Google Scholar]

- Portoghesi, Paolo. 2019. Roma/amoR. Memoria, Racconto, Speranza. Venezia: Marsilio. [Google Scholar]

- Șelaru, Sorin. 2022. Features of Pastoral Ministry in the Romanian Orthodox Communities of Western Europe. Orthodox Theology in Dialogue 8: 43–53. [Google Scholar]

- Tsivolas, Theodosios. 2014. Law and Religious Cultural Heritage in Europe. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Qi. 2008. On the cultural constitution of collective memory. Memory 16: 305–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).