1. Introduction

Latin America shares a common history of colonialism, exploitation, and racial, social, and gender inequality, even though its national realities are different. Since the arrival of Europeans in the 16th century, the continent has been shaped by processes of territorial expropriation, cultural imposition, and the subjugation of native peoples, which has resulted in power structures that perpetuate inequalities to this day. Within this context, Latin American women experience forms of oppression that combine patriarchy and coloniality, which profoundly affects their trajectories and ways of existing. In this way, resistance to suffering and oppression takes on multiple forms, with art being one of the fundamental spaces for this struggle. Frida Kahlo’s work, marked by her personal pain and social marginalization, can be read as a visual expression of kenosis—an emptying that paradoxically generates resistance and reinvention.

In this scenario, art presents itself as a powerful instrument of resistance and transcendence. Through it, historically silenced voices can be heard, allowing their narratives to be reconstructed and suffering to be given new meaning. It thus becomes a means of transcending adversity and building new existential possibilities, especially for colonized communities. Frida Kahlo (1907–1954), one of the most outstanding artists of the 20th century, expressed in her work not only her personal pain but also issues such as identity, the body, suffering, and marginalization. Her art reflects dimensions of the Latin American experience that go beyond Mexico, becoming a testimony to the scars left by colonialism and the forms of resistance that are possible.

Art, in its various manifestations—such as painting, sculpture, dance, and theater—is a means by which the human body expresses and transcends the physical, emotional, and cultural pain imposed by colonization. Although artists like Martha Graham (1894–1991) are outside the Latin American context, her quest to overcome inner anguish through art illustrates the transformative capacity of the body. Similarly, Kahlo uses her works to transform suffering into something greater, addressing cultural, racial, and gender issues and seeking meaning in the midst of adversity, including that stemming from coloniality.

This study proposes to analyze Frida Kahlo’s work in light of the concept of kenosis—emptying as a path to transformation—as interpreted in Latin American theology. The aim is not to discuss the colonization of Mexico specifically, but to understand how Kahlo’s art becomes a way of overcoming, offering a new reading of suffering as resistance and reinvention. At the same time, we problematize the tendency to universalize her figure as the sole representative of Latin America, recognizing that her art reflects common aspects of the Latin American experience, but without reducing the diversity of the continent’s struggles and histories. Among the 200 paintings by Frida Kahlo, the following works were selected methodologically: Unos cuantos piquetitos, Las dos Fridas, El abrazo del amor y el universo, La tierra (México), Yo, Diego y el señor Xólotl, and Diego Rivera y Frida. The choice of these works is justified by the fact that they emblematically portray the themes of suffering, resistance, and overcoming—fundamental elements for understanding the kenotic experience. In Unos cuantos piquetitos, Frida represents the violence and pain of the female body; in Las dos Fridas, she addresses her fragmented identity and the tension between cultural influences; and El abrazo del amor del universo illustrates an integrative and relational worldview essential for Latin American theology, etc. The interpretation of Frida Kahlo’s works based on kenotic theology from a Christian perspective is a proposal by the authors themselves, enriched above all by Latin American theological reflection, with special attention to the feminist theology produced on this continent, as well as other studies that are pertinent to deepening the topic.

Frida Kahlo’s work, often classified as surrealism by European critics, can be interpreted from a different Latin American perspective, which sees it as a testimony to the resistance of historically marginalized bodies. Thus, this study proposes a theological reading that dialogues with the experience of suffering and liberation, highlighting kenosis not as submission, but as a form of reconstruction of being in the face of colonial and patriarchal violence. It is understood that these paintings reflect not only Frida’s personal pain but also the collective pain of the oppressed peoples of Latin America. In the end, the aim is to broaden the understanding of the artist’s legacy and contribute to a theological reflection that dialogues with issues of oppression, gender inequality, and liberation in Latin America.

The article is structured in three parts: first, a theoretical contextualization of kenosis and its relationship with feminist theology and liberation theology in Latin America will be presented; then, it will analyze how Kahlo’s art dialogues with the experience of suffering and resistance in the context of coloniality and gender inequalities; and finally, it will discuss the implications of this theological reading for art as a means of denouncing and reconstructing identities on the continent.

2. Kenosis and Suffering in Latin America

The Iberic colonization of Latin America began in the 16th century and was firmly established in the 17th century, representing a complex process that deeply affected cultures, societies, and local identities. This was not just a territorial victory, but systemic oppression with the aim of total subjugation of indigenous peoples and imposition of a new cultural, socioeconomic, and economic order. Destruction of original cultures like the Inca and Aztec resulted in significant cultural, social, and populational losses. The imposition of new social structures, in conjunction with the exploitation of natural and human resources has always led to the generalized impoverishment of a specific culture and the establishment of severe inequalities. Even with the cultural syncretism that emerged as a form of resistance, the legacy of violence and oppression, including the slavery of Africans and local peoples, continues to influence the subjects of inequality and social justice throughout Latin America. Another emblematic element in this context is the practice of implanted Christianity. In this sense, “legitimation of extreme forms of exploited human work such as the indigenous

encomienda or the trafficking and slavery of Africans left eternally unanswered questions regarding the character of implanted Christianity” (

Beozzo 2022, p. 16).

Therefore, it can be seen that the logic of colonial power was a multifaceted manifestation, dominating not only economic resources, taking over lands, labor, and finances, but also political power, imposing their authority, controlling knowledge, and molding the colonized people’s own subjectivity, imposing a religion that sacralizes all of this domination.

[…] three factors enabled this process. First, they expropriated the populations of their—house, body and land; then, they repressed all forms of the colonized people’s knowledge production, subjectivity, beliefs and values, and feelings. Afterwards, they forced the colonized to learn and assimilate the colonizers’ culture in every sense—technical, material and subjective.

This exploitation lived by Latin Americans, being stripped of their culture, is a thoroughly kenotic experience. However, it must be emphasized that kenosis is not a static and irreversible process. In this context, different forms of resistance emerged in the attempt to regenerate and reclaim identity, aiming to construct new forms of existence. The work of Frida Kahlo is an example of the consequences of this violent depletion. Her art reflects the physical and emotional damage of colonization, especially gender, the struggle to reclaim identity, and the search for an existential feeling among this pain and oppression.

From the perspective of kenotic theology, Frida Kahlo’s works reflect an experience of emptying through her art. Just as in Christianity, where art leads to the experience of Christ, in Kahlo’s work, art also expresses the experience of pain, suffering, and transformation. Art, in this sense, reflects the experience of the artist, her culture, and the reality of the context in which she is inserted, creating a link between personal emptying and artistic manifestation. Frida Kahlo’s art and the theology of kenosis are related here based on three main aspects: the emptying of the self, pain as a path to transcendence, and the resignification of suffering through art. This relationship will be presented later in the analysis of the works.

3. Kenosis as a Model for Liberation

Kenosis is not just an abstract concept, but a concrete act of God who is in solidarity with humanity, especially with those who are at the margins of society and suffer injustice.

Pope Francis has mentioned, in some documents, the importance of self-emptying and service to people as part of Christian life. In the Apostolic Exhortation

Evangelii Gaudium (

Francisco 2013, p. 201), although he does not use the word kenosis, he emphasizes the need for the church to empty itself for the sake of the people. It encourages humility, surrender, and service.

In the 2024 document, the Encyclical Letter Dilexit nos—on the human and divine love in Jesus’ heart, in number 34, he writes about a close God who overcomes all distances: “God is close to our life, living among us. The Son of God became incarnate and ‘emptied himself, taking the form of a servant’” (Phil 2:7). This can be seen when, in the document, he emphasizes his conversation with the Samaritan woman; he meets Nicodemus in his dark night; he lets the prostitute wash his feet; and he does not condemn the adulterous woman. In the same letter, he affirms that “God wanted to come to us by humbling himself, by making himself small. […] His love mingles with the daily life of his beloved people and becomes a beggar for an answer, as if asking permission to show his glory” (p. 202).

One of the greatest expressions in Christianity, a God who reveals himself to human beings, is identified in the word kenosis: a God who lowers himself. Derived from the Greek verb

ekénōse (to empty), in Christianity, it designates the emptying of oneself (

Sesboüé 1982, p. 3;

Lacoste 2004, p. 983). And in the text of Philippians 2:7, kenosis describes the humiliation of Jesus, who, being divine, chose the condition of a servant, culminating in his death on the cross. Paradoxically, this humiliation reveals the superabundance of divine power, culminating in the resurrection.

In the prologue to the Gospel, John (1,14) shows the divine Word that turned into flesh. In this sense, to the Greek spirit, it was not conceivable to have greater opposition than between logos and sarx. In other words, the divine becomes flesh. This stage of service begins with the incarnation when God empties himself of divine glory to live a fragile and mortal human existence. Garcia Rubio stresses that kenosis theology leads to the encounter with the kenotic God “who ‘empties himself’ to make room for the creation, always respecting human autonomy and the laws of nature” (

Francisco 2024, p. 179). There is no contradiction in the vision of the kenotic God.

Rubio continues:

from the God of liberation and the God of creativity, from the God who is love itself, it is not hard to accept that, for this love, this God that is omnipotent because of his divine nature can even freely ‘empty himself’ to allow the other to be himself […] Admirable and disconcerting dynamic of love: meeting the other, being at their level to watch them grow. […] The true power is the power of Love. This is how God is the all-powerful.

So, we can see the importance of this rediscovery of God–Love and his self-emptying to become equal to his creation, giving them space and freedom to rise up to him. In the New Testament, the word kenosis expresses the reality of Jesus Christ, as God, being the second person of the Trinity, took on the human condition since “to be known and to know humans, he must meet humans, relate to them and surrender himself to relate” (

Dos Santos and Xavier 2008, p. 113). The Father is the start of kenotic action, but the Son is the full realization because the kenosis of the Son is the kenosis of the Father through the Holy Spirit.

The analogy made by the Sacred Scriptures is very significant because this descent invites human beings to descend into their deepest intimacy so that they can be reborn and go up to meet God. Simone Weil says that God takes the first step towards human beings: “We cannot take a single step towards the heavens. God crosses the universe and comes to us” (

Weil 1952, p. 78).

Certainly, the biblical notion of creation and contingency, as well as the historicity of our existence, make it possible to think of being as an event. This is most notable in the New Testament, especially in the kenosis of Christ’s incarnation. According to

Vattimo (

2004, p. 30), the kenosis of Jesus is therefore presented as something compatible with the processes of secularization and as a model for these processes, since a God who empties himself is presented as the most appropriate image for the cultural sensibility of our time.

In this sense, “it is from secularization of emptying being a historical event that can be correlated to the image of the weakening of God in the history of salvation” (

Candiotto 2018, p. 440). Kenosis can also be considered, by the way God, in Jesus Christ, was crucified. Crucifixion, as kenosis, goes hand in hand with the suffering of millions of people who were uprooted from their countries by colonization, went through concentration camps, and died simply because they belonged to a different ethnic group than the one in power.

We understand that God’s understanding of truth, reason, and progress, in short, is that almighty God is not only troubled because of atheism and modern and post-modern secularization but also because of increased suffering. Suffering was intensified by the Holocaust and its concentration camps; the advent of the nuclear age and the anxiety of endangered species; increasing economic and social inequalities and misery; and newfound patriarchy in Western societies, which continue to oppress both men and women. The dilation and plurality of this experience of suffering compromised the idea that progress would lead to a better and more humane society, just as the power of reason would replace, once and for all, violence and other forms of irrationality (

Candiotto 2018, p. 444).

Here, we find the experience of the Latin American people who suffer from social inequality, hunger, unemployment, and the colonization of culture, religion, and political power. Faced with suffering and the understanding that God created human beings and withdraws from creation, there is the perception of an absent, distant God who leaves human beings relegated to the domination by the strongest, and not a God who, out of love for the creation, withdraws so that it can have freedom. The question arises: how is it possible that God, in his omnipotence, allows himself to die on the cross?

God’s act of withdrawing allows for human autonomy (freedom). In this kenotic movement, Christians are invited to participate actively and critically in God’s suffering, which is revealed in the radical weakness and suffering of the crucified (

Candiotto 2018, p. 446). The theology of God’s self-emptying demonstrates his solidarity with human suffering. This divine solidarity manifests itself, especially in the suffering of women in a patriarchal society, who are exploited at work, are domestic violence victims, and are subjected to imposed masculine values that empty them.

Along the same lines, Mary Betty Rodríguez Moreno (

Rodríguez Moreno 2019), in her text

Fundamentos de la kénosis con perspectiva de mujer. Una lectura de Filipenses 2, 5–11, presents a concept of kenosis that distances itself from traditional interpretations and contextualizes it from the perspective of women and the socio-cultural reality of the first century. She does not define kenosis simply as emptying or humiliation, but rather as a countercultural action that subverts the established order; it is a transformative action and not a simple act of submission or passive abnegation. For the author, this action starts with humility and surrender in order to promote dignity and equality. This is a pertinent theological reflection for delving into Frida Kahlo’s kenotic analysis.

Kenosis consists of a critical stance towards oppressive power structures and a questioning of oppressive institutions (social and religious), which justified the submission of women and marginalized peoples (

Rodríguez Moreno 2019, p. 12). In addition, kenosis’ relational aspect must be emphasized in the interpretation of Philippians. It is communal. Therefore, Christ’s kenosis becomes a model for interpersonal relationships, which must be marked by humility, service, and solidarity, attitudes that break with the notion of hierarchical power.

A more inclusive reading is necessary that distances itself from a reading that associates kenosis with humiliation and passive suffering, especially of women, subverting the traditional meaning. Value resignification is needed, where humility and surrender, which were seen as feminine characteristics and oppression, become resistance and liberation instruments (

Rodríguez Moreno 2019, p. 5). For the author, when trying to understand kenosis in Philippians 2:5–11, it is essential to take into account the community mentality of the time, with an emphasis on the concept of honor and shame. In this pericope, kenosis can be understood as an alternative proposal to that society, breaking with hierarchy and pre-established gender roles (

Rodríguez Moreno 2019, p. 7). Therefore, the kenotic movement is active, relational, countercultural, and transformative. This critical understanding is capable of subverting the dominant order, promoting the dignity of marginalized peoples, and redefining social values.

In the same vein as the kenotic movement, pain as a path to transcendence and the resignification of suffering through art become instruments of resistance and liberation.

4. Kenosis in the Female Experience: Deconstructing Patriarchism

As this research theme consists of highlighting theological reflection about kenosis based on some of Frida Kahlo’s artistic productions, we must always analyze this work from a Latin American feminist perspective. There are several ways of associating kenosis with women’s suffering. In this item, we look to examine the implications of Jesus Christ’s kenosis in the fight against pain and oppression. We use the image of a suffering God who is humiliated upon incarnating and being crucified.

Elisabeth Shüssler Fiorenza coined the neologism Kyriarchy to express the rule of the emperor, lord, father, and husband over his subordinates to express that not all men dominate and exploit women indifferently. There is an intellectual framework and a cultural ideology that produces a complex social pyramid of gradual domination and subordination. In this process, some exercise power over others, and it can be men and/or women who are at various levels of subordination (

Fiorenza 2000, p. 32).

Latin American theologians Amparo Novoa Palacio and Olga Consuelo Vélez Caro, in their article La categoría Kénosis: una lectura desde la perspectiva de género, make important connections between kenosis and gender theology that are aligned with the proposal of our reflection. First, they identify the contradiction between these two themes in classical theology. Understood as sacrifice and self-giving, kenosis was often used by sexist ideologies to justify the oppression of women and promote their submission, as defended by preachers and biblical commentators.

As such, the meaning of kenosis for men should not be the same for women. Men, because of their inclination towards self-glorification, need to hear a message of emptying and humility in order to welcome God’s grace. In the case of women, whose cultural identity is often shaped around self-sacrifice, they need to renounce processes of self-denial: “It is incompatible and anti-evangelical to demand that women adopt a posture of emptying themselves, denying their being or sacrificing themselves for the sake of others, within a patriarchal mentality that makes them invisible and places them in a second-class position” (

Novoa and Vélez 2010, p. 174).

One of the most fascinating approaches explored by the theology of gender relations, according to the aforementioned authors, is the idea of kenosis as “intercession”. Kenosis acts as a critical element in deconstructing the association between God and patriarchal power. One of the aims of this theology is to interpret Jesus’ kenosis as a challenge to the dominant male power structures and as a support for the creation of a new humanity based on compassion and mutual love. However, the greatest challenge is for gender relations theology to be kenotic. According to these thinkers, to achieve this, it is necessary to avoid the temptation to replace patriarchal power with gynocentrism. Renouncing self-imposed emptying does not imply that women become new agents of oppression (

Novoa and Vélez 2010, p. 177).

Furthermore, in a kenotic theology of gender, the most significant issue is the approach to the idea of God. Historically, this theology has sought to replace masculine symbols with feminine ones. However, we believe that in order to dismantle patriarchy without falling into the trap of gynocentrism, it is essential to reconsider the question of religious imagery and language. This revision implies an effort to imagine and speak of God from the perspective of kenosis. However, the theology of gender relations also needs to progress hermeneutically so that the understanding of kenosis is not limited to an interpretation that could, in fact, justify the suffering of women. The emptying of women should not be seen as submission, just as, in the case of men, it is not restricted to the mere condemnation of their arrogance. This hermeneutic understanding must be translated into attitudes, behaviors, practices, and social functions, from which equality is not just formal, but effective (

Candiotto 2018, p. 448).

Novoa and Vélez (

2010, pp. 180–81) point out that reflection on kenosis is one of the most fruitful paths for a theology of gender relations. This kenotic perspective on gender is fundamental for denouncing oppressive structures, as well as rescuing the historical Jesus’ way of existing, which makes the denunciation of oppression and inequality inseparable from self-giving. This quest for liberation from oppressive structures does not simply imply reversing the roles of the oppressors, making women take control of the world and become the new paradigm of humanity. On the contrary, it is essential to cultivate an inner freedom and unconditional love that allows us to maintain peace in the midst of difficulties, love in the face of hatred, meekness in times of belligerence, and the moral authority of one who does not allow herself to be corrupted by the means to achieve ends, but seeks it with sincerity in her heart. This means following Jesus through a renewed faith so that we share the same feelings as him and fight for the structural transformation of human relationships that oppress us and generate inequality.

In social analyses, it is essential to recognize the inequality related to women’s roles in the economic and political spheres, especially their situation of poverty in the globalized economy. This situation occurs through traps created by multinational companies, which, with the support of international institutions, exploit women’s labor. According to Ivone Gebara, a Latin American feminist theologian, the illusion is created that globalization has opened up spaces for women, but in fact, they are low-paid work spaces marked by instability: “we continue to be dispossessed of our bodies and our workforce” (

Gebara 2017, p. 17).

It is no different in scientific analysis in general, such as in the humanities for example. According to Ivone Gebara, it is precisely from this plural and complex place that human sciences ignored, to a certain extent, the condition of gender until the second half of the 20th century, or rather, ignored one gender and affirmed another. They reflected on the masculine human as the universal and, within it, included the feminine as a subordinate reality or entirely dependent on the masculine (

Gebara 2010, p. 19). Did Frida Kahlo live this universality?

5. Frida Kahlo—A Ribbon-Laced Bomb1

Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo liked to say she was born in 1910, declaring herself as the daughter of the Mexican revolution led by Emiliano Zapata and Francisco ‘Pancho’ Villa (

Jamis 1992, p. 20). However, she was actually born on 6 July 1907. Her father was a German Jewish immigrant, and her mother was a devout Mexican Catholic. At the age of six, she suffered from polio, which left her right leg deformed. She spent nine months bedridden. As a child, she experienced the terrible pain that would accompany her throughout her life. In 1922, Frida entered a normal school. She was an irreverent young woman with a rebellious character and was very different in the way she dressed

2.

In 1925, at the age of 18, Frida suffered a terrible accident. The bus she was riding on collided with a streetcar. It left a lasting mark on her body and her story. An iron bar went through her left hip and out her vagina. Her right leg was fractured in eleven different places, her right foot was crushed, her shoulder, spine, and pelvis were injured, and two ribs and her pelvis were fractured (

Jamis 1992, p. 78). The doctors did not believe she would survive. Frida was in terrible pain. After a month in hospital, she returned home, her studies were interrupted, and she endured a hard convalescence. After this accident, she wore orthopedic vests

3 for most of her life and even spent time in a wheelchair.

It was the time between pain and immobility that led her to start painting. Her mother had the idea of putting a mirror on the canopy of her bed and providing painting materials. In Frida’s case,

“[…] Therefore, painting is not born out of what is known as a ‘precocious vocation’. It emerges under a double pressure: a mirror above her head that harasses her, and deep inside her, the pain that comes to the surface. Two essential elements combined… and painting comes, laboriously, sweetly, it emerges”.

Thus, her activity as a painter began exactly when she felt the most pain and was immobilized in orthopedic vests, which were real instruments of torture for her. It was a time when she felt alone. In the midst of all her pain, art represented a new path. Frida discovered that painting really was her life.

The years between 1929 and 1935 were difficult for the young Mexican. She married a famous muralist of the time, Diego Riviera, known for his political paintings, commitment to the Communist Party, and numerous love affairs. They moved to the United States, she suffered two miscarriages, and Diego cheated on her twice, once with her own sister. After a time in the United States, they returned to Mexico against Diego’s will. However, her health deteriorated and she suffered a third miscarriage. Due to intense pain in her right foot, all five toes were amputated. She later had to have her foot amputated: “Everyone was very apprehensive about breaking the news to the painter, and what a surprise it was when they told her: ‘Why would I want feet to walk on, when I have wings to fly on?’” (

Jamis 1992, p. 80).

Frida Kahlo’s marriage to the Mexican painter who preceded her by twenty years was full of intense passion but was also permeated by frequent betrayal and abandonment. Both shared significant interests, such as a passion for painting and Mexican and communist ideals, as well as a deep curiosity and interest in life. It was a marriage marked by a series of reunions and separations, alternating between moments of great tenderness and intense pain, anger, dependence, construction, and destruction. Until the end of her life, Frida loved him with an obsession that generated suffering in equal measure. Despite Frida’s extramarital relationships, Diego remained the central axis of her existence, her main point of reference. Was Frida the result of male domination?

Megan Clay (

Clay 2013, p. 251) states, “finding a voice through art can be a visionary, creating space to speak out against the injustice of the systems that imprison us both personally and politically”. In this sense, art is configured as a space where it becomes possible to express experiences other than writing, which, according to the author, has its origins in patriarchy.

Frida’s support for indigenous ideals and “Mexicanness” can be found in her art. She combats injustice, violence, and gender inequalities. Her struggle for Mexican indigenous people’s rights is constant (

Peñuela Salgado 2017, p. 6).

Peñuela Salgado (

2017, p. 9) states that even as a communist with a clear position against imperialism, she never stopped faithfully representing typical Mexicans and this made her impact felt worldwide. In this case, from her position as a white woman, the daughter of a German father and an indigenous Catholic mother, Frida Kahlo experiences the culture of the colonized people and gender inequality. The widespread reach of her art and position against the hegemonic kyriarchy in vigor, as Fiorenza writes, bring signs of hope.

6. Frida Kahlo: Kenosis and Hope

By acknowledging the pain and stories that permeate colonization, breaking with this process challenges the structures of power and oppression, but also sows fertile ground for building new identities and relationships nourished by empathy and respect. Thus, an invitation to imitate divine kenosis on the part of human beings, each from their own position, becomes a powerful tool in the search for a restorative and dignified coexistence by transforming scars from the past into seeds of hope for the future. Art, political engagement, and the search for justice and human dignity for all people, but specifically for those marginalized, can be ways of resisting.

As well as being a teacher and a great artist, Frida Kahlo was politically engaged, mobilized people, and was an art lover. How, then, can this woman’s experience, regarding art, political activism, and her bodily experience, in terms of emptying, signal possible openings for transcendence and hope? How can her existence say something to Latin American women?

First, we present

Breton’s (

1969, p. 38) statement about Frida Kahlo’s art, which, according to him, was surrealist, but she does not accept this denomination because she claims to paint only for herself and her feelings: “Yo nunca he pintado mis suenõs. Sólo he pintado mi própria realidade (

Kahlo 1995, p. 287)”. Here, we see a movement born in Europe and, even without the artist having any contact with this movement, she is “labeled” a surrealist. Could this not be a colonizing element? Before looking at the painter’s own reality and style, we usually try to fit her into a style of painting that was consolidated in Europe. This framing must be understood since she was considered one of the great European artists!

Considering that women were only admitted to art schools in the 19th century, Amparo Serrano de Haro (

de Haro 1997, p. 356), an art history professor, presents an analysis of how difficult it was for women to be recognized in art before surrealism because it was very difficult to accept women’s intellectual and creative equality. Until that time, women were present in art, but they had no recognized face or personality. Therefore, for the history teacher, surrealism is presented on a forced basis that

“insists on the difference between male and female artists by attributing certain characteristics (unconsciousness, spontaneity, ignorance, innocence, innate wisdom, rational incapacity) that relegate them to the role of the lesser or second-order artist (it is common for women to be encouraged to work in marginalized fields of great art: engravings more than paintings, drawings more than paintings, short stories more than novels, etc.). Despite this sexist or chauvinistic attitude, surrealism forces the configuration of a female portrait of the artist”.

Recognizing this dimension of surrealism, we can doubt Breton’s ready-made definition of Frida “fitting in” with the surrealist movement. In 1935, Frida summed up, in a single work, the existential physical pain that martyred her:

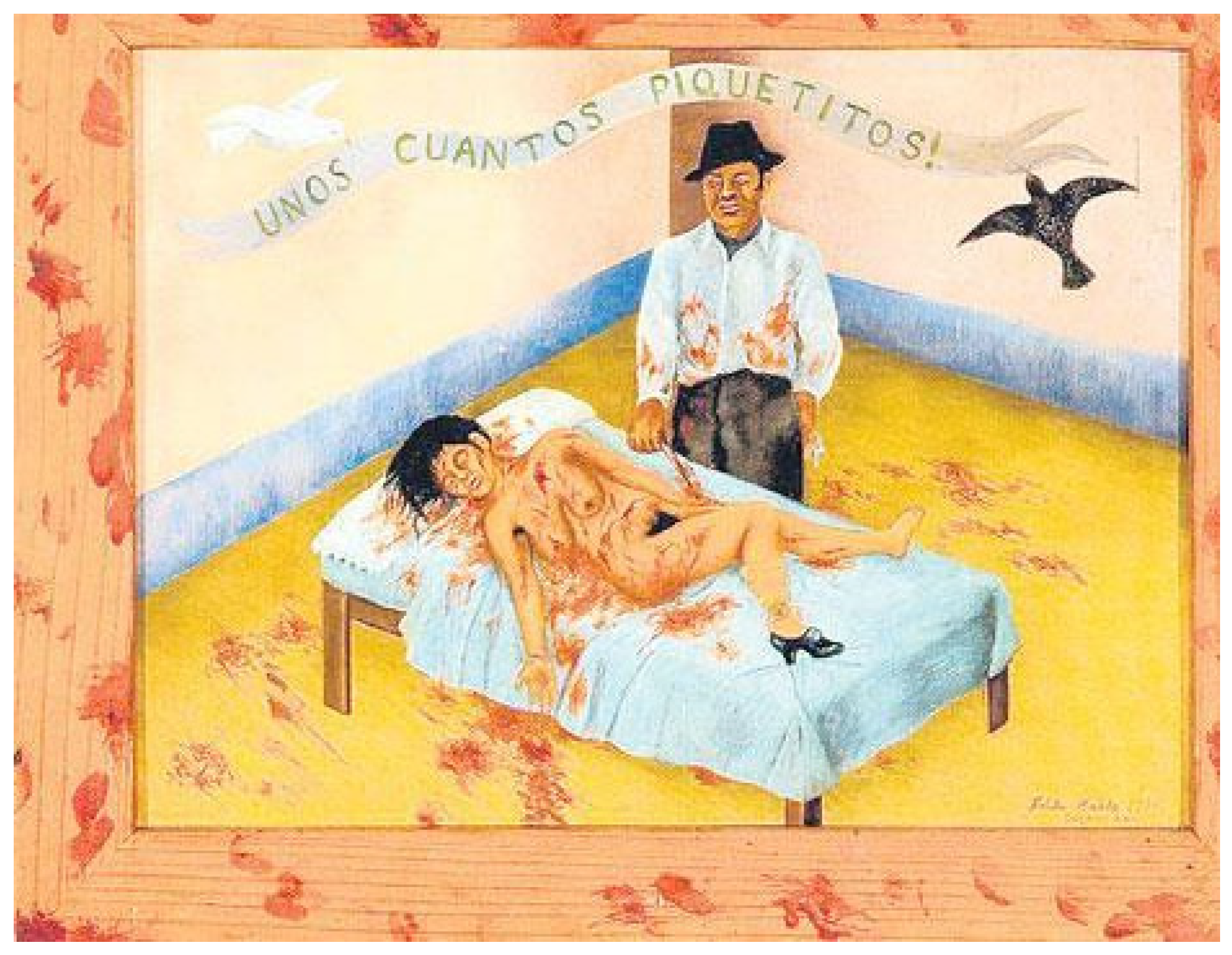

Unos quantos piquetitos! (

Figure A1). The work depicts a murder based on a newspaper report about a woman murdered out of jealousy, serving as the theme for this work by the artist. The murderer justified his actions to the judge, saying that it was just a few blows. The violent act is a symbolic reference to Frida’s personal situation.

At the time, her soul and body were torn apart. Her husband had become involved with her sister Cristina (

Kettenmann 1994, p. 39). In the painting, the pigeons carrying the ribbon with the text, one white and the other black, carry a connotation between good and evil, love and hate, and ambivalent feelings. In a wounded body and soul, with a deformity in her leg, a sequel in her spine, and a troubled relationship with Diego, everything about her cries tragedy. In this painting, blood gushes out of the canvas and invades the frame, as if draining from Frida herself and spreading out into the world. The faces of the man and woman are the faces of Frida and Diego. The work is reminiscent of the tragedies of some people’s daily lives, as she painted from a news report she heard, but it is also reminiscent of a personal tragedy (

Justino 2013, pp. 29–30).

From this troubled situation in Frida’s life, this work can be seen as an illustration of the artist’s psychological state. The wounds caused by brutal male violence seem to symbolize her own emotional damage (

Kettenmann 1994, p. 39). This painting may also portray her desire to self-mutilate, to kill herself for some things and be born for others. She felt mutilated by her pain, in her attempt to get her life back on track, but, physically and morally scarred by pain and betrayal, she felt exhausted: “Frida’s painting is a game between the hopeless battered mutilated body and the infinite mind in which all monsters are unleashed. Works such as The Broken Column (1944) and Without Hope (1945) bear witness to these nightmares. But she is not a woman who turns to lamentation. She faces adversity” (

Justino 2013, p. 32).

Here, we relate the suffering of the great Mexican artist to the exploitation suffered by humanity. She undergoes kenosis by feeling humanity’s suffering. The idea of kenosis can be seen as ‘intercession’, in which the critical element expresses itself through art, deconstructing the association between God and the patriarchal power that makes women invisible or that they need to fit into the only model of humanity, the masculine.

In this case, the work

unos cuantos piquetitos demonstrates that “the cross of Christ is not only God’s identification with the suffering, but God’s real participation in the suffering of the world” (

Moltmann 1972, p. 47). Just as kenosis in Christianity implies surrender and transformation through suffering, Kahlo’s art suggests that pain is not just a burden, but a path to self-knowledge and transcendence. The artist does not limit herself to portraying her pain in a passive way but transforms it into a powerful visual discourse. It can be read as a process of symbolic death and resurrection, similar to the dynamics of Christian sacrifice, but here it is still awaiting resurrection. This idea can be applied to Kahlo’s work, where her suffering is not just a theme portrayed, but a process of identification, transformation, and overcoming.

Among the many works by the artist, we would like to mention two more that represent these characteristics of Frida Kahlo:

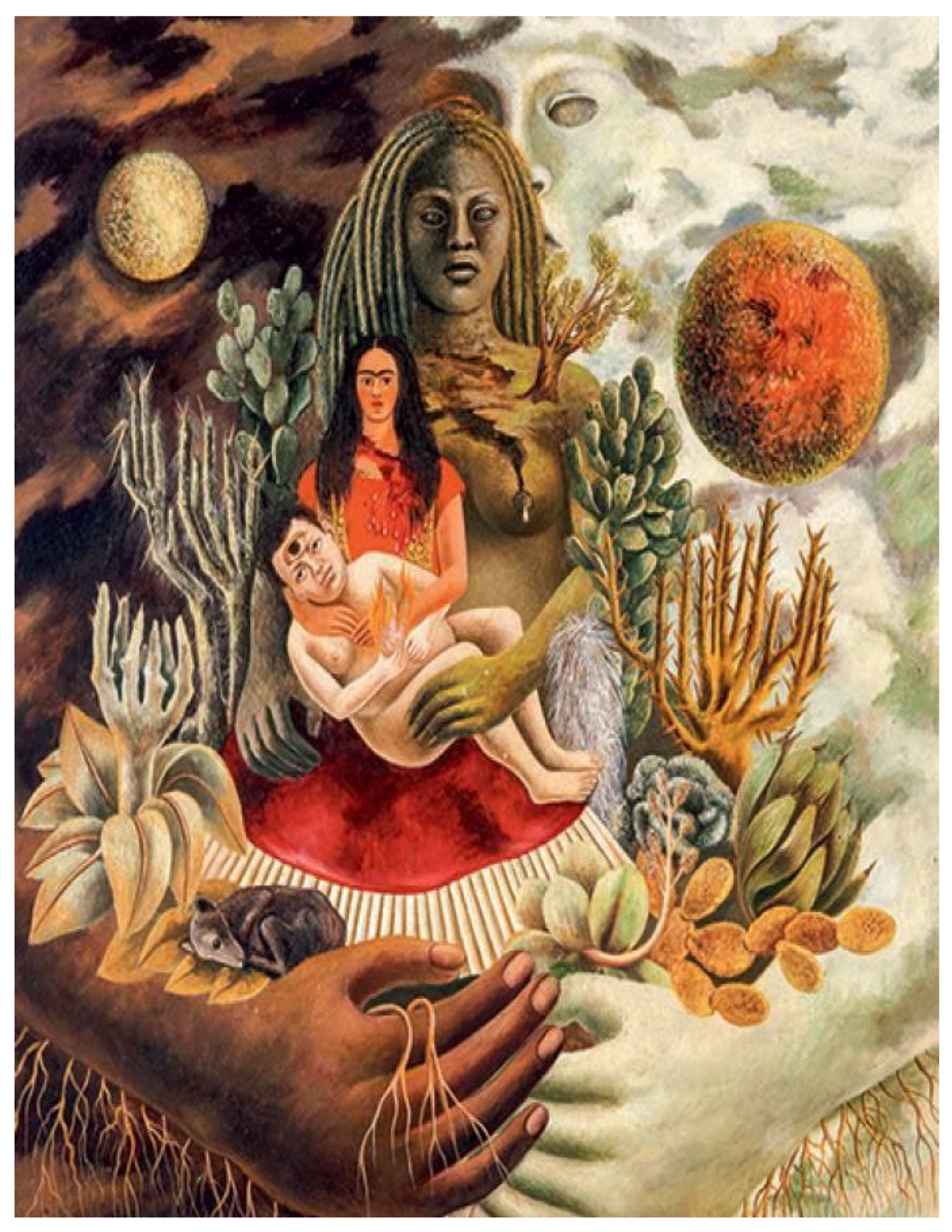

El abrazo de amor y El universo,

la tierra (Mexico),

Yo,

Diego y el señor Xólotl (

Figure A2), and the work

Diego Riviera and Frida (

Figure A3). The first,

El abrazo del Amor de El Universo, la tierra, Yo, Diego y el señor Xólotl, was painted for her exhibition in 1949. By this time, Frida had fully embraced a nationalist lifestyle in public, shown in her clothing as well as nature and animals in her works. Here, too, she presents her lived relationship with nature, part of her culture. When considering women in art, there is ambivalence and daring in her work. Despite her failed relationship with motherhood, her dependence on Diego Riviera shows her identification and participation with ancient Mexican culture and cosmogony. It shows her belief in the duality of human/divine, day/night, cold/hot, and male/female.

Frida confessed that she “always wanted to hold Diego in her arms like a newborn child” (

Vera 2013, p. 304), which clearly appears in the center of the work. The whole symbolic composition is protected by an archetypal Mother Earth who surrounds both characters in her womb, protected by the duality of the universe. The dog, señor Xólotl, is interpreted as a symbol of the sleeping death from which Frida is saved by the sacred entity. For Chilean poet and historian Luiz Roberto Vera (

Vera 2013, p. 306), there is a triangle in the center of the image that reiterates, through its composition, the triad in which the painter represents herself as Madonna/Isis/Coatlicue not holding the Christ child or an embalmed Osiris, but the Quetzalcoatl (Diego)/Xolotl twins of Mesoamerican tradition. Frida compares the figure of Diego to the Great Mesoamerican Goddess. The dog (Xolótl) who would guard the realm of the dead and the Mexican Earth Goddess (Cihuacoatl) from whose womb all the flora that would characterize Mexico would be born are examples. In the work, Cihuacoatl supports the sterile Frida. While from the Goddess’ breasts flows a river of milk alluding to fertility, from Kahlo flows—to a lesser extent—a river of blood in reference to her infertility (

Reis et al. 2019, p. 138).

Reading this work, we realize how dependent she is on Diego. She wants to hold him in her arms, but she only has him in her mind, as symbolized by the image of the eye in the center of his forehead. By analyzing the work in relation to the kenosis of intercession, could we see here the emptying of the woman from her perspective as a professional and even as a lover? We could interpret it as a social and personal annihilation, in which patriarchal culture introjects in women the sacrifice of their own being and the designation of love as self-denial. “Art arises at the frontier of extreme experience, where suffering and beauty coexist in a paradoxical way” (

Bataille 1957, p. 61). Kahlo transforms her pain into something that goes beyond the mere representation of suffering, creating a space of transcendence similar to the concept of kenosis.

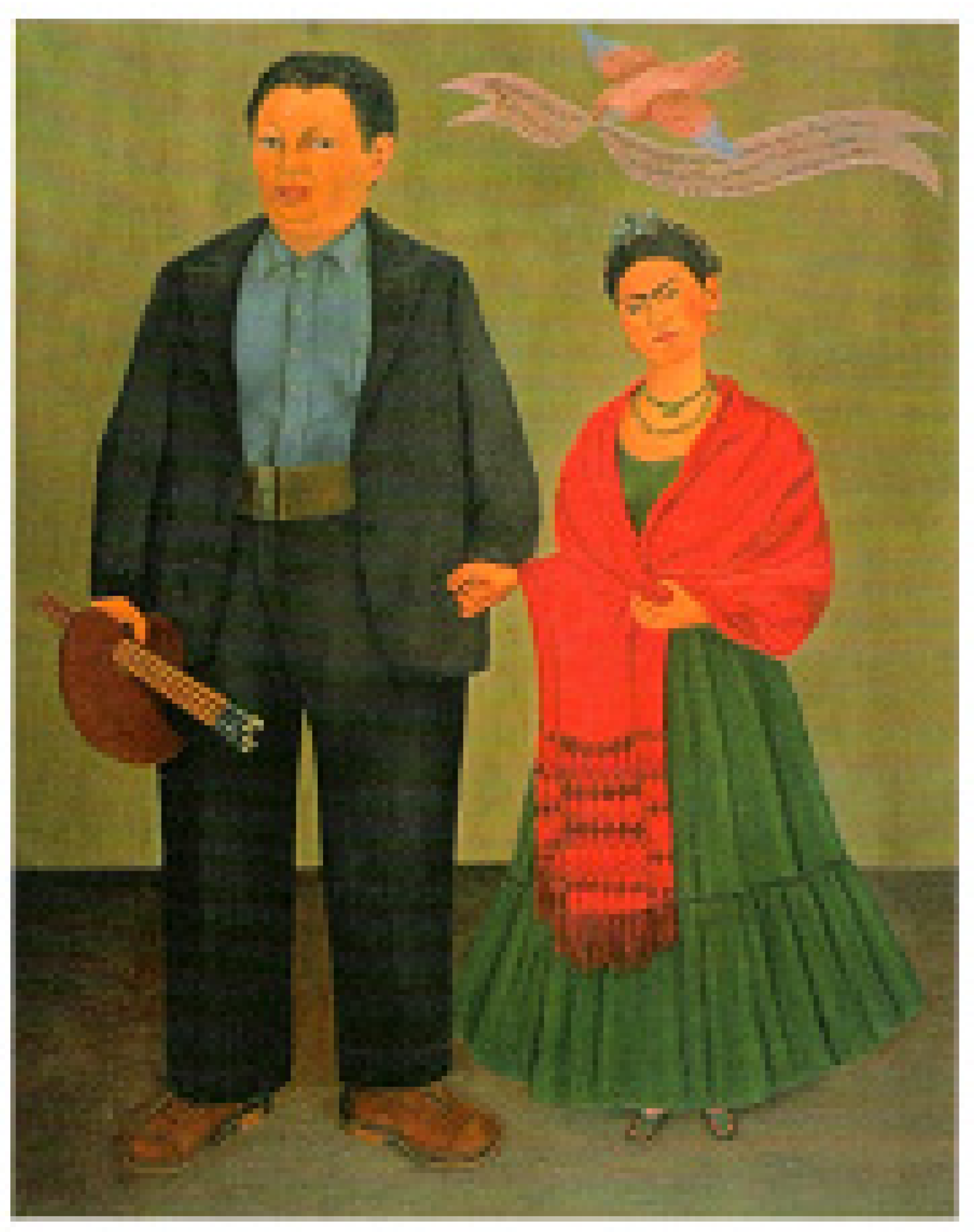

The second work we mentioned, Frida and Diego Riviera, depicts marriage. The couple is holding hands. Frida is apparently floating, while Riviera seems to be supporting her. He appears larger than her and seems to be one step ahead. “The painter carries a paint palette that announces his social status in Mexican society—famous, recognized and talented painter” (

Reis et al. 2019, p. 135). Frida, on the other hand, only complains to herself about her social position as a wife, as she appears holding his hand. In this sense, we can say that what “would be on display in the artist’s self-representation would be a kind of caricature of the traditional love partner—a fragile, inferior woman on the rise through marriage” (

Reis et al. 2019, p. 135). Would not the role of women imposed by society appear here? “For Frida, art was the very substance of life, a means of transforming pain into visible and powerful images” (

Herrera 1983, p. 32). The act of externalizing pain through art is reminiscent of the spiritual emptying process of kenosis, where the experience of suffering becomes a path to meaning.

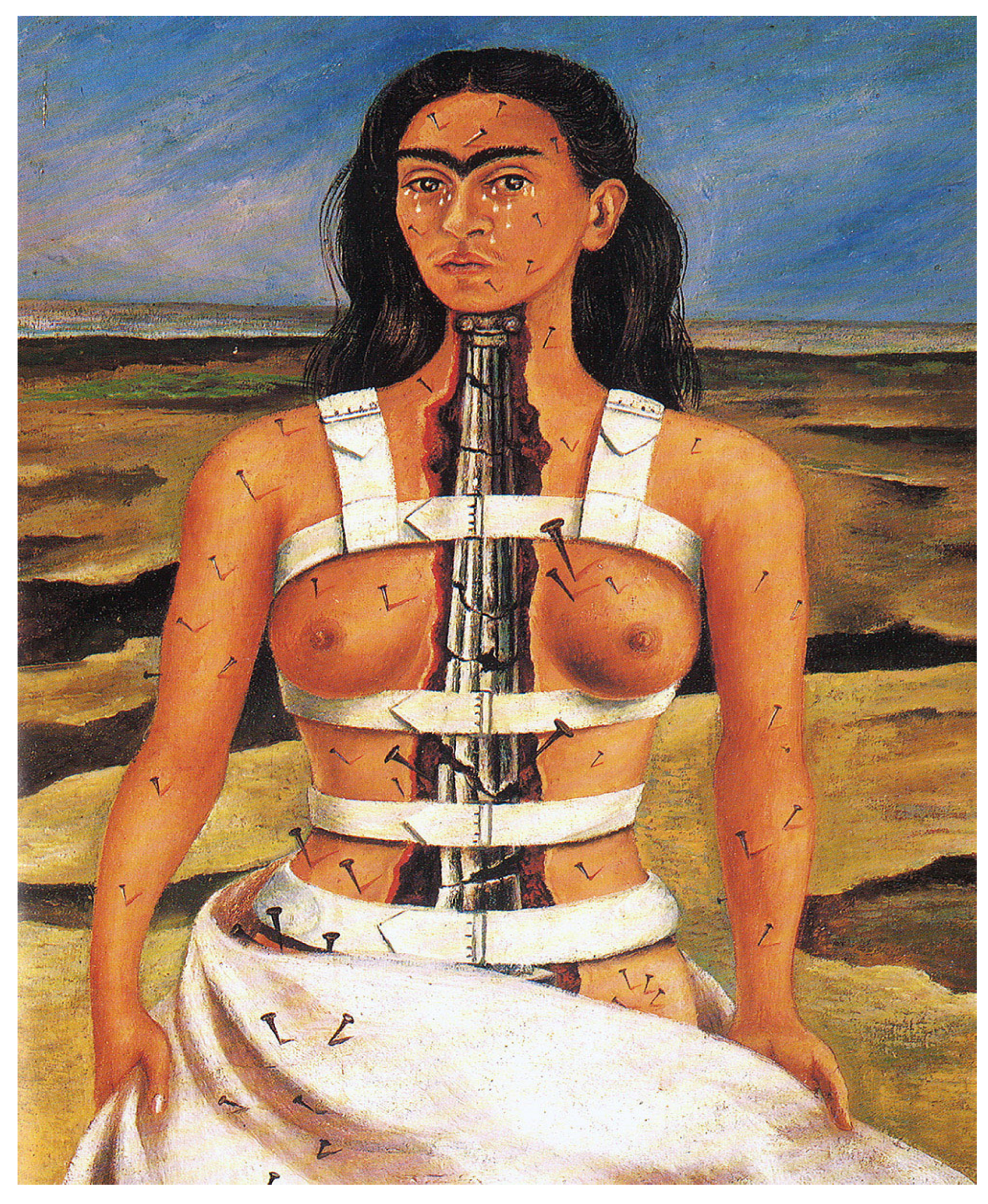

Another intense pain she experienced was wearing up to 28 different orthopedic vests between 1944 and 1954. Her most famous work from this period is

The Broken Column, from 1944 (

Figure A5). In 1950, she underwent seven operations on her spine. Here, we see the possible signs of a great mystery. Frida’s case is extraordinary because, from the same place where she exudes so much pain, she draws her energy to survive and to live, and, from her daily life and existence, she becomes a great painter, a strong woman in a fragile body. Her art dialogues with life, with it being ontological, metaphysical, and paradoxical. Metaphysics is understood here in the broad sense by Merleau-Ponty as the full experience of paradoxes (

Merleau-Ponty 1966, p. 166).

As in the Christian tradition, where kenosis refers to the ‘emptying’ of Christ when he assumed the human condition and suffered the cross, Frida Kahlo’s emptying of herself is identified when she exposes her physical and emotional pain through her art. This emptying appears in various paintings where her body is fragmented, blended with nature, or dissolved into symbols of suffering. The fragmentation of the self in his paintings reflects a process of emptying that can be read as a parallel to Christian kenosis. In the case of

The Broken Column, Kahlo depicts herself with a fractured body, supported by a broken Ionic column, in an image that echoes the exposure of suffering. The act of painting her pain can be seen as a form of kenosis, an emptying that transforms her and resignifies her existence: “Frida Kahlo not only painted herself, but reconfigured her identity through pain and fragmentation” (

Ankori 2002, p. 55).

In this way, Kahlo was able to construct a profoundly intimate and universal art. Her past is a cruel memory that will never leave. The scars are present on her body. We identify here the torn bodies of so many Latinos who suffered the pain of hard work, exploitation, enslavement, poor living conditions, hunger, violence, and oppression suffered by colonization.

A few points to consider regarding Frida Kahlo concern her thinking of herself as a work of art rather than as an artist—just consider how many self-portraits she painted and her connection to nature as an alter ego. The value of self-portraits lies in their ability to bear witness, to reflect the masterpiece that is essentially the artist herself—the true creation. Frida’s path “springs from within, out of intimacy and solitude” (

Justino 2013, p. 37). “Her work is visceral, always giving birth to something. A conquest over her life. A ritual resurrection, as well as a sacrifice. Her entire existence is like an embryo, a bloody rupture, both earthly and physiologically” (

Cardoza y Aragón 1988, p. 38).

According to Amparo Serrano de Haro, “the self-portrait would be the identity search in front of the mirror, it would also be the rehearsal of ‘another’ stare, foreign to the ‘colonization’ of the male stare” (

de Haro 1997, p. 358). This image creation is not as immediate, spontaneous, or realistic as it might appear at first glance. Hayden Herrera (

de Haro 1997, p. 358) analyzes the changes that Frida’s various images undergo and finds the transformations rooted in her marriage to Diego Riviera because he liked to emphasize the indigenous aspect of Frida’s lineage, exalting her as authentic and primitive. After living in another country, she began to dress in Mexican folk costumes, especially those from the Tehuana province. The choice to make this change indicates a revaluation of popular art, but also a social choice. Although the costume functions as a metaphor for her identity, it is also a sign of her Mexican character, even if this character indicates a white woman with better social conditions than most.

To demonstrate the analysis above, the work

Las dos Fridas (1939) (

Figure A4) reveals a European Frida, more sensitive, emotional, and fragile, and a Mexican Frida, stronger, resistant, and haughty, comparisons that are possible because they are part of the imagination, culture, history, and collective memory (

Fachin 2017, p. 473). In this work, the hearts of both Fridas are exposed and connected to each other. One has cut an artery with scissors, staining her white skirt with blood, while the other holds a portrait of Riviera. In the end, their works belonged to the private, everyday world, of which women were a part. Raquel Tibol writes, “Frida’s very early discovery of the private within the collective emblematized the intellectual and artistic sector that believes that Mexicanness is possible, something that has challenged Western uniformity since its emergence” (

Tibol 2004, p. 18). In Christian theology, Christ’s kenosis is not just about the suffering itself, but about a process of surrender that generates redemptive meaning. For Kahlo, art also operates as a means of resignification: by externalizing her pain, she not only shares her suffering but transforms it into something new.

Frida makes us look back at pain, injustice, and humiliation and does not close us in this circle. On the contrary, it is an invitation to restore the beauty that has been disfigured by the emptiness that oppresses us by going beyond it, which gives us access to the relationship with God that always goes through human relationships. It thus overcomes dualisms, the dichotomy of subject and object, and the distance between human beings and their own bodies. The painter imprints the sensation of pain in her work. We see here that suffering finds hope in art where suffering is overcome not in itself, but in the mobilization towards transcendence. Due to her suffering, Frida Kahlo went beyond herself; she returned to her daily life with other self-knowledge that was more elaborate, complex, and resignified by her own existence.

Although she was recognized during her lifetime for her work, such as in exhibitions in Paris in 1953, New York in 1939, and a major exhibition in Mexico in 1953, she is much better known around the world for her troubled life. In 2010, a major retrospective of her work was held in Berlin and Vienna. Fortunately, today she is better known for her work. However, the world was slow to recognize how special her paintings were. Recently, her exhibition has been recognized around the world as the most original artist in Mexican tradition (Cf.:

Justino 2013, pp. 22–23).

7. Final Considerations

Frida Kahlo’s trajectory included exposing suffering through her paintings, visualizing the body in pain, and turning the private world public. The whispers of exposed pain show us a path to reclaim dignity in the midst of pain. Thus, art recognizes the voices of many other faces that cry out, images that ushered in a time in which otherness breaks through, “they say” and ask us. Therefore, art presents itself as theological insofar as it generates a place where kenosis takes place to open up a space for epiphany and the manifestation of otherness. Thus, art explores our senses and touches our sensitivity, allowing the human face that becomes the body to appear and become a sacred place, a territory where the epiphany of the face takes place, a place where the face of another human being can question us. This is because we are sensitive, and we have the capacity to feel empathy and compassion, to be affected by the other, by their joys, suffering, and hope without superimposing one culture on another.

The analysis of the selected works shows Frida’s kenotic movement as the emptying of the self, pain as a path to transcendence, and the resignification of suffering through art. Thus, the kenotic movement in Kahlo’s works, based on the reading carried out, became an instrument of resistance and liberation, as it is an active, real movement that subverts the order of power.

The Latin American woman painter assumes her culture in the midst of a colonized continent, deemed inferior, breaking through the woman’s place in the midst of the universal model of humanity—the male—not without suffering. In her works, we find a space to cry out and express the injustice and pain suffered due to the culture of patriarchal domination, as is well represented in the painting Unos quantos piquetitos.

Would she not have also denounced the pain of so many other women who could not or did not find a way to express themselves like she did?

So, consider the possibility of reinterpreting the Christian sacrifice based on kenosis theology read from a female perspective in which sacrifice consists of self-emptying and limitless love, usually interpreted as personal and social annihilation, as was noted in Frida. She was not totally excluded from public office to the detriment of her daily life, but placed in the shadow of her husband, Diego Riviera, as demonstrated in her painting, Diego Riviera and Frida.

She questioned her belonging among her people and culture. She was only sure of her roots when she lived abroad in the United States. Upon returning, she no longer took off her colorful clothes and ornaments. It was not because of European colonization, as demonstrated in her work Las dos Fridas.

In the face of such analyses, we verified the significance of considering a kenotic gender theology that contemplates the incarnation and crucifixion of Jesus as a consequence of his personal freedom. Even though Frida showed no signs of Christianity, her mom was a faithful Catholic. As such, kenosis presumes an authentic personal identity that can be freely chosen and where one can give their all. In Frida’s case, it was what she believed in, the love for her country. The fruit of her self-emptying was that her work broke through the structural domination in power without getting attached to the cultural constructions that organize society in a typically patriarchal manner. Frida Kahlo constructed a new way of living in the midst of so much adversity and suffering.